Abstract

Background:

To investigate whether changing the play environment in primary schools to one that includes greater risk and challenge increases physical activity and reduces body mass index (BMI).

Subjects/Methods:

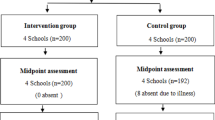

A 2-year cluster randomised controlled trial was undertaken in 16 New Zealand schools (years 1–8). Intervention schools (n=8) redesigned their play environments to encourage imaginative and independent free play by increasing opportunities for risk and challenge (for example, rough-and-tumble play), reducing rules and adding new playground components (for example, loose parts). Control schools (n=8) were asked to not change their play environment. A qualified playworker rated all school play environments at baseline and 1 year. Primary outcomes were moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (7-day accelerometry) and BMI z-score, collected in 840 children at baseline, 1 and 2 years. Data were analysed using generalised estimating equations.

Results:

Multiple changes were made to the school play environments resulting in a significant difference in overall play evaluation score between intervention and control schools of 4.50 (95% confidence interval: 1.82 to 7.18, P=0.005), which represents a substantial improvement from baseline values of 19.0 (s.d. 3.2). Overall, schools liked the intervention and reported many benefits, including increased physical activity. However, these beliefs did not translate into significant differences in objectively measured physical activity, either as counts per minute (for example, 35 (−51 to 120) during lunch break) or as minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (0.4, −1.1 to 2.0). Similarly, no significant differences were observed for BMI, BMI z-score or waist circumference at 1 or 2 years (all P>0.321).

Conclusions:

Altering the school play environment to one that promoted greater risk and challenge for children did not increase physical activity, nor subsequently alter body weight. Although schools embraced the concept of adding risk and challenge in the playground, our findings suggest that children may have been involved in different, rather than additional activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In many countries, children and youth are not meeting global physical activity guidelines,1 a finding that is particularly striking in older children. Recent meta-analyses highlight the considerable challenges faced in substantially increasing physical activity in children, whether via community-, school- or family-based approaches.2, 3, 4, 5 Despite these challenges, schools remain an opportune environment for intervention simply because most children attend school regularly and thus provide a captive audience. Although comprehensive school activity programmes may be more successful,6, 7 a lack of large, high-quality studies5, 8 creates uncertainty regarding the effectiveness of different approaches.9, 10 Given the lack of effect seen in many studies,5 investigation of alternative approaches, particularly those that involve little to no additional burden for school staff or the curriculum, is warranted. One unexplored approach is to try and increase physical activity by involving some risk and challenge.

Risky play holds an evolutionary role that allows children to test their limits within a known environment, and has multiple demonstrated benefits for development.11, 12, 13 Not exposing children to gradually increasing risk and challenge over time is thought to lead to an inability to assess real danger over the longer term.11, 14 However, concern about accidents and litigation influences what is perceived as acceptable play within the school playground, with many schools limiting rough-and-tumble play (for example, physical wrestling games or contact sports) or tree climbing.15, 16

Whether altering the school environment to provide greater opportunities for children to experience appropriate levels of risk and challenge during outdoor active play is a good way of increasing physical activity in children has only been examined in short-term studies.17, 18 The aim of our 2-year cluster randomised controlled trial (PLAY) was to determine whether providing greater opportunities for risk and challenge in primary schools increased physical activity and reduced relative body weight over the long term. A secondary aim considered the effect of the intervention on how children interacted with one another which forms the basis of a separate paper.19

Materials and methods

PLAY was a cluster randomised controlled trial in 16 primary schools in the Otago (n=8) and Auckland (n=8) regions of New Zealand. Schools were randomised to intervention (provided with funds to assist with altering school play spaces) or control (asked to not change anything in their school play spaces) conditions for 2 years (1-year intervention, 1-year follow-up). Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Otago (reference 10/077) and Auckland University of Technology (reference 10/95) Ethics Committees.

Recruitment of schools and students

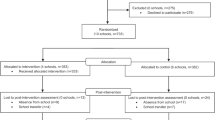

State primary schools (years 1–8 that are fully funded by the state and co-educational) with at least 150 pupils, and a school decile ranking of 1–6 were eligible. New Zealand schools are ranked into deciles from 1 to 10, where 1 indicates the 10% of schools with the highest proportion of pupils from low socioeconomic areas and decile 10 indicates the 10% of schools with the lowest proportion.20 Eleven schools met these criteria within the Otago region and 31 in Waitakere City (within the Auckland region). Waitakere City (population: 186 447) and the Otago region (population: 193 803) are similar in population size,21, 22 but are culturally quite different.23 Eleven schools were approached in Otago and 10 in Auckland and recruitment stopped once 16 schools (eight in each region) provided informed consent to participate (November 2010 to March 2011). Pairs of schools were created by matching for region, school roll and decile ranking, and were randomly assigned to intervention or control by tossing a coin (Supplementary Table 1).

Although all children in intervention schools were exposed to the intervention, only children in school years 2 and 4 were invited to participate in outcome assessments. These years were chosen pragmatically to cover a wide age range (typically ages 6–9) and enable 2-year outcomes to be collected. There were no exclusion criteria. Information sheets and consent forms were sent home with all children in these year groups from each school, and signed consent was obtained from parents. Baseline data were collected from March to December 2011 and 2-year data collection was completed in December 2013.

Outcome assessments: schools

At baseline and 1 year a qualified playworker24, 25 undertook an evaluation of the play environment in each school according to a schedule of seven items rating opportunities for (i) risk and challenge, (ii) engagement with natural elements, (iii) ability to actively manipulate and change the play environment (for example, loose parts), (iv) wheeled play (for example, bicycles and skateboards), (v) ball games, (vi) children to socialise, and (vii) quality of independent access (no restrictions on the ability to access all parts of the school). Each item was scored from 1 (very poor) to 5 (excellent) and an overall score was determined for the whole school play environment (maximum score of 35). At each time point, principals completed an 18-item questionnaire assessing physical activity policies within their school (break time, using physical activity as a punishment, promotion of community activities, adequacy and availability of facilities during school/after hours, enjoyment and promotion of physical activity regardless of skill level, amount and quality of physical education, and safety issues).26 Principals indicated whether the policies were fully in place (score of 3), partially in place (2), under development (1), or not in place (0). At 2 years, exit interviews were undertaken to explore the teachers’ thoughts about PLAY and the associated outcomes for their school.27

Development of schools’ playground action plans

The researchers, playworker and school community worked together to develop a playground action plan that met the needs of each school community. Following baseline evaluations of their play space, each intervention school was provided with a list of tailored suggestions for improvements. This was specific to each school but could include the addition of more interactive play equipment, and alterations to school rules and policies that may limit risk-taking during play (for example, no tree climbing, separation of older and younger children into physically separate play areas), with all alterations meeting playground safety standards. The research team then met with each school community to finalise the plan. Although intervention schools were provided with initial start-up funds of NZD$15 000, the majority of recommendations involved no to little cost, such as leaving trees that had been cut down in pieces or letting the grass grow long to encourage imaginative play, re-purposing real-estate signs for sledding down hills, purchase of raincoats and gumboots to allow outside play when wet, and using plastic piping and sand for water play. Developing each school’s playground action plan from assessment through to implementation and completion took ~1 year and Supplementary Table 2 illustrates the changes made by schools.

Outcome assessments: children

Measurements were obtained at baseline, 1 year (2–3 months after changes to the intervention school play environments) and 2 years (follow-up) by researchers blinded to group allocation. Children’s height, weight and waist circumference were measured in light clothing without shoes using standard techniques during school time. Height was measured using a portable stadiometer (seca 213, Hamburg, Germany) and weight using electronic scales (seca 813, Seca, Seca 213, Hamburg, Germany). Waist circumference was measured at the umbilicus using a non-elastic tape (Lufkin 2 m Executive Thinline w606PM, Apex Tool Group, Sparks, MD, USA). All measures were obtained in duplicate with a third undertaken if the first and second measures did not fall within the maximum allowable difference (0.5 cm for height, 0.5 kg for weight and 1.0 cm for waist), and the mean taken from the two closest measurements. Body mass index (BMI) z-scores were calculated using World Health Organisation reference data.28

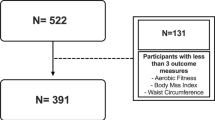

All children wore an accelerometer (ActiGraph GT3X, Actigraph Corp, Pensacola, FL, USA) 24 h a day for 7 days, positioned over the right hip (accelerometers were removed for bathing, showering and water-based activities). Accelerometers were initialised using ActiLife (version 6, Actigraph Corp) in uniaxial mode using 15 s epochs. Data were cleaned and scored using an automated script developed in MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) that removes the appropriate sleep period for each day for each child individually, to avoid sleep being misclassified as sedentary time.29 A day was considered valid if there were at least eight valid awake hours.30 Non-wear time (awake hours only) was defined as at least 20 min of consecutive zeros.30 Participants were excluded from the analysis if fewer than three valid days of wear were obtained. Activity intensities were calculated using the Evenson cut-points developed for children aged 5–8 years.31 The specific start, end, break and lunch times for each school were used within the MATLAB programme to obtain filtered activity information for particular time periods (school day, break time, lunch time and ‘whole day’, which excludes the sleep period).

Statistical analysis

Assuming a mean (s.d.) of 100 (35) for minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA),32 intraclass correlation of 0.04 and correlation between repeat measures of 0.4,33 our study has 80% power (5% level of significance) to detect a difference in MVPA of 15 min with 97 children in each group. Assuming corresponding figures of 0.7 (0.85), 0.03 and 0.85 for BMI z-score,34 our study has 80% power (P<0.05) to detect a difference of 0.2 in BMI z-score with 106 participants per group. Accounting for clustering (2.56 for MVPA and 2.17 for BMI z-score) and 25% drop-out increases our required numbers to 331 per group.

The data were analysed according to modified intention to treat following the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials statement, which has been extended for cluster randomised trials.35, 36 Data were analysed using Stata 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

School-level data

Because pairs of schools were matched before randomisation by area and decile, paired t-tests were used to compare scores of the control and intervention schools for each of the seven items assessed during the play space evaluations that were undertaken at baseline and 1 year. The 18-item activity policy scores were summed and expressed as a percentage of the total maximum score (54). Regression analysis adjusting for the first measure was used to compare the final policy measure.

Student-level data

Because schools (not students) are the primary sampling unit, generalised estimating equations with an exchangeable correlation matrix were used to analyse the data. This type of model takes into account the correlational structure within each school and estimates population averaged models. Robust s.e.’s (based on the sandwich estimator) were used to calculate the confidence intervals and P-values. The models included the baseline variable and an interaction term between time and group so that differences at both year 1 and year 2 could be estimated. The models also included terms for sex, age at the initial assessment and time difference between assessments as well as terms for the pairs to take account of the randomisation procedure. Analysis was undertaken using modified intention to treat. That is, participants were included in the analysis if they had at least one repeat measure at 1 and/or 2 years for the relevant outcome.

The accelerometry data are presented for the whole day and specific periods of interest (for example, break times) as counts per minute (CPM, estimate of overall activity) and minutes of MVPA. Minutes of MVPA are adjusted for total time awake (as this differs within and between children) and time spent in less intense activity (sedentary and light activity) using the logarithm of the ratio of the proportions of both variables and fitted using the Stata procedure fmlogit, which fits a fractional multinomial logit model by quasi maximum likelihood.37 The estimate for proportion of MVPA during each time period (for example, school time) was multiplied by the number of minutes during that time period based on the means of all observations (for example, for school time this was 360 min). The difference between estimates is therefore presented in minutes. As the observation period for each child was different (depending on the child’s sleep duration and the start, finish and break times for each school), the estimated differences in proportion were scaled so that they applied to 360, 30, 60 and 800 min for the school day, break time, lunch time and the whole day (that is, mean total valid minutes, excluding sleep time), respectively.

The missing data were imputed using chained equations assuming that the data were missing at random.38, 39 Data for all the outcomes, CPM, BMI and BMI z-score were imputed in the same model, which also included terms for sex, age, group, school, school decile and accounted for the clustered nature of the study. Thirty data sets were imputed using a burn in length of 750.

Results

All eight intervention schools made substantial changes to their school play spaces, which promoted greater risk and challenge through building new areas (hills and tunnels), adding more dynamic equipment (for example, a Kompan ‘Supernova’ that requires co-ordination and teamwork to use; Supplementary Figure 1), or via relaxing the rules (letting children ride their bicycles or scooters on school grounds, allowing children to climb trees or play outside in the rain). Children were able to engage more with natural elements, create imaginative play opportunities with loose parts (carrying tree stumps around to form a spaceship or a jumping game where the ground cannot be touched) or long grass (places to hide, roll around in, throw mown grass at each other). Some schools also ensured greater equity in access for all ages, or made different aspects of the playground more attractive (Supplementary Table 2). These changes to the school play spaces were evaluated by the playworker at 1 year with a higher score indicating a better play space (Table 1). At 1 year, intervention schools provided more opportunities than control schools as indicated by a significantly higher overall summed score from the seven components (mean difference: 4.50 (95% confidence interval: 1.82 to 7.18, P=0.005)) as well as for the individual components of interest including risk and challenge (1.00 (0.11 to 1.89, P=0.033)) and wheeled play (1.25 (0.18 to 2.32, P=0.028)). Apart from safety surfacing, control schools did not make any substantial changes to their play environment. Nor were school policies relating to physical activity different between intervention and control schools; mean (s.d.) scores at 2 years were 76.4% (10.6) for control schools and 76.2% (10.4) for intervention schools (P=0.568).

The eight intervention schools were all positive about their experience in the PLAY Study. Interviewees reported many benefits resulting from intervention and these included their belief that children were fitter and more active, and that the altered play environments provided many more play opportunities as well as being more dynamic. These findings are discussed in detail in a separate paper.27

Figure 1 describes the flow of children throughout the study. A total of 840 were measured at baseline and 630 of these children remained at 2 years. Final analyses were undertaken in children for whom we had baseline and at least one follow-up measure (n=704 for MVPA and n=743 for BMI z-score). Only four children (0.5%) withdrew from the study, but a further 180 children were lost to follow-up (21.4% of the 840 baseline participants) from moving out of the area. Similar characteristics were observed between groups at baseline (Table 2). At baseline, 2.7% of children were underweight, 73.4% normal weight, 16.0% overweight and 7.9% obese.28

No significant differences were observed between control and intervention groups in break time or lunch time activity at either 1 or 2 years, or in overall activity (CPM) across the school day (for example, 0900–1500 hours) or whole day (time the child woke up until they went to sleep) at 1 year (Table 3). However, at 2 years, CPM were significantly lower in the intervention group compared with the control group during the school day (adjusted difference, 95% confidence interval: −63, −107 to −20, P=0.005). A similar effect was seen for minutes of MVPA across the school day (−3.3 min, −6.1 to −0.6), P=0.017) and whole day (−3.8, −7.1 to −0.5, P=0.022). The small sample of schools limited school-specific analysis but examination of change in adjusted CPM during school time at 1 and 2 years indicated differences with no particular pattern for intervention or control schools (Supplementary Figure 2). Imputation of missing data did not influence the estimates for physical activity. For example, the imputed estimates for CPM during the whole day were −6 (95% confidence interval: −32, 20) at 1 year and −28 (−53, −2) at 2 years compared with −6 (−37, 24) and −28 (−66, 10) in the original analysis.

Table 4 demonstrates that no statistically significant differences were observed at either 1 or 2 years for BMI, BMI z-score, waist circumference or waist-to-height ratio. As was observed for physical activity, imputed estimates did not alter our conclusions; estimates at 1 and 2 years for BMI z-score were −0.02 (−0.08, 0.04) and 0.02 (−0.04, 0.08) compared with −0.02 (−0.06, 0.02) and 0.02 (−0.04, 0.07) in the original analysis.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that schools were successful in altering their play spaces to encourage greater opportunities for risk and challenge in children’s play. Proposed changes were well received by schools, with all noting positive outcomes for children including improvements in behaviour and greater participation in physical activity.27 However, these anecdotal views of school staff were not supported by objective evidence from accelerometry, with similar levels of total activity and MVPA observed between intervention and control children across the study. We also found no effect of increasing risk and challenge in the school playground on anthropometric outcomes, which is perhaps not surprising given we did not affect physical activity or include a dietary component to our intervention.

It is difficult to compare our findings with other published studies because even though risk is an important component of play,11 studies investigating the role of risk and challenge in promoting physical activity are scarce. The only relatively comparable intervention is the Sydney Playground Project, which educated parents and teachers about the benefits of risk-taking in play.18 Although these sessions changed teacher and parental attitudes to risky play,40 the actual intervention of incorporating loose parts (that is, equipment with no obvious play value) had little effect on physical activity itself,18 similar to our findings. Although these authors reported a significant effect of the 13-week intervention on MVPA at break time (P=0.006), at only 1.8 min, this difference seems unlikely to be clinically significant given the errors inherent in estimation of MVPA, even when using objective measures such as accelerometry.5 Furthermore, this difference at break time did not translate to differences over the whole day, a compensatory effect that has been observed in other physical activity interventions in children.2, 41 It is also possible that the short-term nature of the Sydney intervention produced a novelty effect; although follow-up measurements were undertaken at 2 years, these were only undertaken in 16 children from one school, and unsurprisingly were not significant at this time. Our findings and those of the Sydney project should not be taken to mean that changing the school playground to include more risk and challenge is not beneficial for children or, indeed, schools in a wider context. Interviews with intervention schools clearly showed they believed the intervention to have been beneficial for their school community.27 It is feasible that use of accelerometry to assess physical activity may obscure real changes in the type or quality of play that intervention children reportedly engaged in such as building huts, climbing trees and imaginative play. Although these activities are designed to increase risk and challenge, they may not necessarily increase MVPA and accelerometers are not particularly effective at accurately measuring the upper-body movement involved in these behaviours.42 Alternative measures of activity assessment in children such as the System for Observing Play and Leisure Activity in Youth43 also classify physical activity into intensities and do not measure type or quality of play itself.

Alternatively, the lack of intervention benefit we observed may have been because our population was already sufficiently active (baseline mean MVPA of 67 min), leaving little opportunity for increases in MVPA. Although choice of physical activity cutoff can substantially affect levels of MVPA,44 CPM—which reflect overall activity and are independent of intensity cutoffs—also did not increase in our study, suggesting that choice of arbitrary intensity cut-point is not relevant. Certainly, the literature is clear that increasing physical activity has proven to be extremely challenging in children,2, 3, 4 whether referring to family-based3 interventions or those targeting the school environment45, 46 or curriculum.47 Why it is so difficult to substantially increase physical activity in children is not clear, but increasing evidence suggests that Comprehensive School Physical Activity Programs may offer the best solution,6 with several studies demonstrating their efficacy.7, 48, 49 Although schools in New Zealand are required to include many aspects of Comprehensive School Physical Activity Programs as part of the curriculum,50 analysis of our policy questionnaire illustrated that schools could still improve in this area, with overall scores of 76%.

The main strengths of the PLAY study were the extended follow-up over 2 years, which allowed us to evaluate potential sustainability, and the high retention rate (84–88% for the two main outcomes). All previous play interventions have been of short duration lasting a few weeks to months.18, 51, 52 Because of the inclusion of two different regions within New Zealand with markedly different ethnic distributions, we had a sample that reflected the wider New Zealand population.53 Because of the strong association between socioeconomic status and body size in children54 and a perceived greater need, we intentionally recruited less advantaged schools. Given the financial constraints within such communities, many of the recommendations made to each school involved zero to minimal cost changes including pipes for water play, boxes, tarpaulins and logs, which most schools, regardless of income, would have the capacity to incorporate. Although we did provide a reasonable level of funding to each school, most of this was spent on a single item of fixed equipment (Kompan ‘Supernova’), which represented only a small proportion of the overall changes made within each intervention play environment. Very few children withdrew from the study (n=4 of the baseline sample) and although a further 21.4% moved away from the area, this level of ‘transience’ or ‘churn’ reflects national data in New Zealand (15.7% nationwide55 and 22% in South Auckland schools).56 Finally, we measured physical activity objectively, and for a much longer period that is typically examined with most similar studies being limited by duration, size and/or measurement methods.

Our study also has some limitations. Because this was a community intervention in a real-world setting, each school developed their own plan with input from the research team that took variable amounts of time for implementation. Although this individualised approach should be viewed as a strength, it also meant that changes were being implemented in an ongoing manner as opposed to them all occurring together such that there was no single ideal time to measure changes in physical activity. For this reason, we chose to avoid measuring immediately after the majority of redevelopments to avoid any observable differences occurring due to novelty. It was also not possible to blind the play space evaluator to the school’s condition because of their involvement in assisting schools to develop their playground action plans. Some accelerometry data were also missing (4.4% at baseline, 6.3% at 1 year and 6.4% at 2 years), because the devices were not always worn as requested or malfunctions occurred. However, the results from imputation analyses showed that missing data did not change the estimates and made no difference to our findings.

In conclusion, although schools embraced the concept of introducing more risk and challenge to the school play environment and made numerous effective changes, these changes did not translate into significant benefits to activity or weight. It is possible that interventions such as ours will not influence physical activity to the extent that is required to get children more physically active and increase MVPA, but will instead improve the play experiences of children. Studies investigating children’s play would therefore benefit from the development of a tool which is able to more definitively assess how children play and any associated benefits. However, our findings also highlight the continued difficulties faced in effectively increasing physical activity in children over the long term. As current methods focusing solely on physical activity are only minimally successful at best, attempts to reduce excess body weight in children need to incorporate both physical activity and diet.

References

Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, Guthold R, Haskell W, Ekelund U et al. Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet 2012; 380: 247–257.

Metcalf B, Henley W, Wilkin T . Effectiveness of intervention on physical activity of children: systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials with objectively measured outcomes (EarlyBird 54). BMJ 2012; 345: e5888.

Brown HE, Atkin AJ, Panter J, Wong G, Chinapaw MJ, van Sluijs EM . Family-based interventions to increase physical activity in children: a systematic review, meta-analysis and realist synthesis. Obes Rev 2016; 17: 345–360.

Biddle SJ, Braithwaite R, Pearson N . The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity among young girls: a meta-analysis. Prev Med 2014; 62: 119–131.

Sims J, Scarborough P, Foster C . The effectiveness of interventions on sustained childhood physical activity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled studies. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0132935.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Comprehensive School Physical Activity Programs: a Guide for Schools. Department of Health and Human Services: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2013.

Cohen KE, Morgan PJ, Plotnikoff RC, Callister R, Lubans DR . Physical activity and skills intervention: SCORES cluster randomized controlled trial. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2015; 47: 765–774.

Parrish AM, Okely AD, Stanley RM, Ridgers ND . The effect of school recess interventions on physical activity: a systematic review. Sports Med 2013; 43: 287–299.

Kriemler S, Meyer U, Martin E, van Sluijs EM, Andersen LB, Martin BW . Effect of school-based interventions on physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents: a review of reviews and systematic update. Br J Sports Med 2011; 45: 923–930.

Dobbins M, Husson H, DeCorby K, LaRocca RL . School-based physical activity programs for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; CD007651.

Sandseter EB, Kennair LE . Children's risky play from an evolutionary perspective: the anti-phobic effects of thrilling experiences. Evol Psychol 2011; 9: 257–284.

Gleave J . Risk and Play: a Literature Review. Play England: Playday, London, UK, 2008.

Brussoni M, Gibbons R, Gray C, Ishikawa T, Sandseter E, Bienenstock A et al. What is the relationship between risky outdoor play and health in children? A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015; 12: 6423–6454.

Christensen P, Mikkelsen MR . Jumping off and being careful: children's strategies of risk management in everyday life. Sociol Health Illn 2008; 30: 112–130.

Thomson S . Do’s and don’ts: children’s experiences of the primary school playground. Environ Educ Res 2007; 13: 487–500.

Evans J . Problems in the playground. Education 3–13 1994; 22: 34–40.

Bundy AC, Luckett T, Tranter PJ, Naughton GA, Wyver SR, Ragen J et al. The risk is that there is 'no risk': a simple, innovative intervention to increase children's activity levels. Int J Early Years Educ 2009; 17: 33–45.

Engelen L, Bundy AC, Naughton G, Simpson JM, Bauman A, Ragen J et al. Increasing physical activity in young primary school children – it's child's play: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Prev Med 2013; 56: 319–325.

Farmer VL, Williams SM, Mann JI, Schofield G, McPhee JC, Taylor RW . The effect of increasing risk and challenge in the school playground on bullying in children: a cluster randomised controlled trial (PLAY). Pediatrics 2016 (In Press).

Ministry of Education New Zealand. School Deciles. Available at: http://www.education.govt.nz/school/running-a-school/resourcing/operational-funding/school-decile-ratings/ (accessed 21 September 2015).

Statistics New Zealand. QuickStats About a Place – Waitakere City. Available at: http://www.stats.govt.nz/Census/2006CensusHomePage/QuickStats/AboutAPlace/SnapShot.aspx?id=2000006&type=ta&ParentID=1000002 (accessed 17 October 2014).

Statistics New Zealand. QuickStats About a Place – Otago Region. Available at: http://www.stats.govt.nz/Census/2006CensusHomePage/QuickStats/AboutAPlace/SnapShot.aspx?id=1000014&type=region&ParentID=1000014 (accessed 17 October 2014).

Statistics New Zealand. QuickStats About Culture and Identity: 2006 Census. Wellington, New Zealand. Available at: http://www.stats.govt.nz/Census/2006CensusHomePage/QuickStats/quickstats-about-a-subject/culture-and-identity.aspx (accessed 10 November 2014).

Children's Play Information Service (CPIS) No. 14: What is Playwork? 2009. National Children's Bureau: London, UK. Available at https://www.google.co.nz/search?q=Children%27s+Play+Information+Service+(CPIS).+No.+14%3A+What+is+Playwork%3F+2009&ie=utf-8&oe=utf-8&client=firefox-b&gfe_rd=cr&ei=KPetWOrFKYTr8weS9Zv4AQ (accessed on 23 Feb 2017).

Play Wales. Playwork. Available at: http://www.playwales.org.uk/eng/playwork (accessed 8 April 2013).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention School Health Index: a Self-Assessment and Planning Guide. Elementary School Version Centers for Disease Control: Atlanta, Georgia, USA 2005.

Farmer VL, Fitzgerald RP, Williams SM, Mann JI, Schofield G, McPhee JC et al. What did schools experience from participating in a randomised controlled study (PLAY) that prioritised risk and challenge in active play for children while at school? J Adventure Educ Outdoor Learn 2016 (In Press).

de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J . Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. B World Health Organ 2007; 85: 660–667.

Meredith-Jones K, Williams S, Galland B, Kennedy G, Taylor R . 24 h Accelerometry: impact of sleep-screening methods on estimates of sedentary behaviour and physical activity while awake. J Sports Sci 2016; 34: 679–685.

Esliger DW, Copeland JL, Barnes JD, Tremblay MS . Standardizing and optimizing the use of accelerometer data for free-living physical activity monitoring. J Phys Act Health 2005; 2: 366–383.

Evenson KR, Catellier DJ, Gill K, Ondrak KS, McMurray RG . Calibration of two objective measures of physical activity for children. J Sports Sci 2008; 26: 1557–1565.

Kriemler S, Zahner L, Schindler C, Meyer U, Hartmann T, Hebestreit H et al. Effect of school based physical activity programme (KISS) on fitness and adiposity in primary schoolchildren: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010; 340: c785.

Taylor RW, Murdoch L, Carter P, Gerrard DF, Williams SM, Taylor BJ . Longitudinal study of physical activity and inactivity in preschoolers: the FLAME study. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009; 41: 96–102.

Taylor RW, McAuley KA, Barbezat W, Strong A, Williams SM, Mann JI . APPLE Project: 2-y findings of a community-based obesity prevention program in primary school-age children. Am J Clin Nutr 2007; 86: 735–742.

Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG,, CONSORT Group. Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ 2012; 345: e5661.

Campbell MJ Cluster randomized trials. In: Ahrens W, Pigeot I (eds). Handbook of Epidemiology, 2nd edn. Springer Science+Business Media: New York, USA, 2014..

Williams SM, Farmer VL, Taylor BJ, Taylor RW . Do more active children sleep more? A repeated cross-sectional analysis using accelerometry. PLoS One 2014; 9: e93117.

Sterne JA, White IR, Carlin JB, Spratt M, Royston P, Kenward MG et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ 2009; 338: b2393.

White I, Royston P, Wood A . Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med 2011; 30: 377–399.

Niehues A, Bundy A, Broom A, Tranter P, Ragen J, Engelen L . Everyday uncertainties: reframing perceptions of risk in outdoor free play. J Adventure Educ Outdoor Learn 2013; 13: 223–237.

Ridgers ND, Timperio A, Cerin E, Salmon J . Compensation of physical activity and sedentary time in primary school children. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2014; 46: 1564–1569.

Crouter SE, Albright C, Bassett DR Jr . Accuracy of Polar S410 Heart Rate Monitor to Estimate Energy Cost of Exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2004; 36: 1433–1439.

McKenzie TL, Marshall SJ, Sallis JF, Conway TL . Leisure-time physical activity in school environments: an observational study using SOPLAY. Prev Med 2000; 30: 70–77.

Trost SG, Loprinzi PD, Moore R, Pfeiffer KA . Comparison of accelerometer cut points for predicting activity intensity in youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011; 43: 1360–1368.

Ridgers ND, Fairclough SJ, Stratton G . Twelve-month effects of a playground intervention on children's morning and lunchtime recess physical activity levels. J Phys Act Health 2010; 7: 167–175.

Janssen M, Twisk JW, Toussaint HM, van Mechelen W, Verhagen EA . Effectiveness of the PLAYgrounds programme on PA levels during recess in 6-year-old to 12-year-old children. Br J Sports Med 2015; 49: 259–264.

Huberty JL, Beets MW, Beighle A, Welk G . Environmental modifications to increase physical activity during recess: preliminary findings from ready for recess. J Phys Act Health 2011; 8: S249–S256.

Sutherland RL, Campbell EM, Lubans DR, Morgan PJ, Nathan NK, Wolfenden L et al. The physical activity 4 everyone cluster randomized trial: 2-year outcomes of a school physical activity intervention among adolescents. Am J Prev Med 2016; 51: 195–205.

Hollis JL, Sutherland R, Campbell L, Morgan PJ, Lubans DR, Nathan N et al. Effects of a 'school-based' physical activity intervention on adiposity in adolescents from economically disadvantaged communities: secondary outcomes of the 'Physical Activity 4 Everyone' RCT. Int J Obes 2016; 40: 1486–1493.

Ministry of Education. The New Zealand Curriculum. Wellington, New Zealand. 2016. Available at: http://nzcurriculum.tki.org.nz/The-New-Zealand-Curriculum (accessed 3 November 2016).

Cardon G, Labarque V, Smits D, Bourdeaudhuij ID . Promoting physical activity at the pre-school playground: the effects of providing markings and play equipment. Prev Med 2009; 48: 335–340.

Loucaides CA, Jago R, Charalambous I . Promoting physical activity during school break times: Piloting a simple, low cost intervention. Prev Med 2009; 48: 332–334.

Statistics New Zealand. 2013 Census – Major Ethnic Groups in New Zealand. 2013. Available at: http://www.stats.govt.nz/Census/2013-census/profile-and-summary-reports/infographic-culture-identity.aspx (accessed April 2015).

Shrewsbury V, Wardle J . Socioeconomic status and adiposity in childhood: a systematic review of cross-sectional studies 1990–2005. Obesity 2008; 16: 275–284.

Education Counts: Ministry of Education. Indicator Report: Transient Students. Ministry of Education. Online Report. 2013. Available at: http://www.educationcounts.govt.nz (accessed 26 January 2015).

Child Poverty Action Group Inc. IThe Revolving Door: Student Mobility in Auckland Schools: Auckland, New Zealand. 2014. Available at: http://www.cpag.org.nz (accessed May 2014).

Acknowledgements

We recognise and thank the many children, families, schools and teachers who participated in this research and the research assistants who helped with data collection. The PLAY study was funded by the Health Research Council of New Zealand and the Otago Diabetes Research Trust. VLF was in receipt of a Medicine Award and subsequently a Lottery Health Research New Zealand PhD Scholarship during her PhD study. RWT is partially funded by a Fellowship from the Karitane Products Society (KPS) Limited. This study was retrospectively registered with the Australia New Zealand Clinical Trial registry ID: ACTRN12612000675820.

Author contributions

VLF assisted with study design, was project manager and PhD student on the PLAY study. She completed all accelerometry analyses, assisted with statistical analyses, and wrote the first and subsequent drafts of the paper. SMW was a co-investigator, assisted with study design, was responsible for all statistical analyses and commented on the manuscript. JIM was a co-investigator, assisted with study design and commented on the manuscript. GS was a co-investigator, assisted with study design and oversaw data collection in Auckland, with JCM being the project co-ordinator in Auckland. RWT conceived the idea for the study, was the principal investigator of the project, responsible for overall study design and monitoring of data collection, and re-drafted the manuscript with VLF. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclaimer

The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on International Journal of Obesity website

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Farmer, V., Williams, S., Mann, J. et al. The effect of increasing risk and challenge in the school playground on physical activity and weight in children: a cluster randomised controlled trial (PLAY). Int J Obes 41, 793–800 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2017.41

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2017.41

This article is cited by

-

How can physical enrichment of school playgrounds improve movement behaviours and developmental outcomes in children and adolescents? A systematic review with meta-analysis

International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity (2025)

-

Which school-based interventions work better to combat obesity in children? A network meta-analysis

Systematic Reviews (2025)

-

Waist circumference as a parameter in school-based interventions to prevent overweight and obesity - a systematic review and meta-analysis

BMC Public Health (2024)

-

Play Preferences of Preschoolers According to the Design of Outdoor Play Areas

Early Childhood Education Journal (2023)

-

Physical activity and sedentary time of youth in structured settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis

International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity (2020)