Abstract

Objective:

To examine the relationship of race and maternal characteristics and their association with cord blood vitamin D levels and small-for-gestational-age (SGA) status.

Study Design:

Cord blood vitamin D levels were measured in 438 infants (276 black and 162 white). Multivariable logistic regression models were used to evaluate associations between maternal characteristics, vitamin D status and SGA.

Results:

Black race, Medicaid status, mean body mass index at delivery and lack of prenatal vitamin use were associated with vitamin D deficiency. Black infants had 3.6 greater adjusted odds (95% confidence interval (CI): 2.4, 5.6) of vitamin D deficiency when compared with white infants. Black infants with vitamin D deficiency had 2.4 greater adjusted odds (95% CI: 1.0, 5.8) of SGA. Vitamin D deficiency was not significantly associated with SGA in white infants.

Conclusion:

Identification of risk factors (black race, Medicaid status, obesity and lack of prenatal vitamin use) can lead to opportunities for targeted prenatal vitamin supplementation to reduce the risk of neonatal vitamin D deficiency and SGA status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vitamin D (25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D)) is commonly known for its role in calcium metabolism and bone health, but more recently has gained attention for the significant role it plays in pregnancy and perinatal outcomes. Vitamin D freely crosses the placenta during pregnancy. Thus, levels of neonates at birth depend entirely on that of the mother and, accordingly, several studies have consistently correlated cord blood 25(OH)D levels to those of their mothers.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 In addition, maternal vitamin D deficiency has been linked to decreased fetal growth and birth size in observational studies.7, 8, 9

Maternal vitamin D deficiency is prevalent, the extent of which can be influenced by many variables including skin pigmentation, sun exposure, season, age, vitamin supplementation and obesity. Several large observational studies and meta-analyses have described the association of maternal vitamin D deficiency with pregnancy complications such as pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes and premature birth.10, 11, 12, 13 Racial disparities in maternal and neonatal vitamin D deficiency have been described.1, 14, 15 Vitamin D deficiency is more common and more severe in black mothers.10, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 Racial disparities are also seen with pregnancy complications such as preterm birth, pre-eclampsia and gestational diabetes, as well as adverse neonatal outcomes including low birth weight and small-for-gestational-age (SGA) status.15, 17, 20, 21 However, the majority of studies examined maternal vitamin D levels during the first and second trimesters of pregnancy7, 8, 22, 23 and correlated these levels to neonatal outcomes. Far fewer studies have examined the relationship between cord blood vitamin D levels, which may more accurately reflect fetal levels of vitamin D, and neonatal outcomes.14, 24 Given the racial disparities seen in both vitamin D deficiency and perinatal outcomes, vitamin D has been proposed as part of the explanation for this disparity, particularly with regard to fetal growth and SGA.8

Increased awareness of the growing prevalence of maternal vitamin D deficiency has led to an urgent need for consideration of supplementation during pregnancy. Although studies have shown that supplementation increases maternal and cord blood vitamin D levels, changes in clinical outcomes have not yet been well proven. Thus, sufficient evidence is lacking at this time to recommend routine vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy.12 However, identification of specific risk factors for vitamin D deficiency and the additive effects of these risk factors may lead to opportunities for targeted supplementation with improved outcomes. Thus, the primary purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between race, maternal characteristics, cord blood vitamin D levels and SGA status among infants during one winter season in a Midwestern US population. In particular, we wanted to evaluate the additive effects of race and maternal characteristics such as obesity on vitamin D deficiency and SGA. Our goal was to identify specific high-risk subsets of pregnant women who may benefit from vitamin D supplementation in order to mitigate adverse perinatal outcomes such as SGA.

Methods

Study design and subjects

This retrospective study was conducted at University of Cincinnati Medical Center in Cincinnati, OH, USA. This study was approved by the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center Institutional Review Boards. Previously collected cord blood samples from all singleton births from November 2010 to April 2011 (one winter season) served as the study population. Multiple births and major congenital anomalies were excluded. Maternal medical records were reviewed for the following information: race, prepregnancy body mass index (BMI) and BMI at delivery, insurance status, prenatal vitamin use and maternal complications including smoking, hypertension, diabetes, chorioamnionitis, preterm labor and premature rupture of membranes. Neonatal medical records were reviewed for the following information: gestational age, gender, birth weight, birth length, birth head circumference and SGA status. SGA was defined as weight <10% for gestational age according to the Fenton growth chart25 and the WHO growth chart (for infants of ⩾37 weeks).26 All information was deidentified and entered into a REDCap database.27

Cord blood sample analysis

Cord blood samples were spun and the serum was frozen at −80 °C. Cord blood 25(OH)D levels were analyzed using the LIAISON 25 OH Vitamin D assay (DiaSorin Inc., Stillwater, MN, USA). This is a direct competitive chemiluminescence immunoassay used to quantitatively determine total 25(OH)D concentrations. For categorical analysis of vitamin D levels, we used cutoff values of: sufficient (⩾50 nmol l−1) and deficient (<50 nmol l−1).28, 29, 30, 31

Statistical analysis

Distributions of continuous variables were evaluated for normality graphically using histogram and box plots and are described using means and s.d. or medians with interquartile ranges, if nonnormally distributed.

To explore relationships between race, vitamin D levels and SGA, we first evaluated race as a predictor of vitamin D levels (sufficient or deficient) in cord blood and assessed for potential confounders: Medicaid status, BMI at delivery, hypertension, maternal age and prenatal vitamin use. These results informed the next stage of analyses that examined race and vitamin D levels with the outcome of SGA by assessing potential confounders: race, smoking, pre-eclampsia, maternal age, Medicaid status and BMI at delivery. The χ2 tests or Fisher’s exact tests were used to examine relationships between categorical variables. Independent t-tests were used to examine the relationship between continuous variables and each outcome. Potential predictors associated with each outcome at P<0.2 in bivariate analyses were entered into multiple regression models and evaluated using backward elimination. Statistical significance was declared at α=0.05. SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used to conduct all analyses.

Results

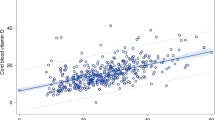

Of the 506 non-Hispanic white and black infants, 438 with available data on vitamin D status, BMI at delivery, prenatal vitamin use and pre-eclampsia/pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) history were included in final analyses. The mean cord blood 25(OH)D level for our study population (n=438) was 46.9 nmol l−1, with a range of 5.0 to 135.8 nmol l−1. Differences in the distributions of cord blood 25(OH)D concentrations by race were evident (Figure 1), with a higher proportion of vitamin D-deficient samples found in the black population. The mean birth weight of our study cohort was 3119 g and 12.8% of our study population was SGA. The mean BMI at delivery was 32.3 kg m−2. Maternal and neonatal characteristics of our study population, stratified by race, are shown in Table 1. Compared with whites, blacks had a lower mean cord blood 25(OH)D level and higher incidence of SGA (P⩽0.01).

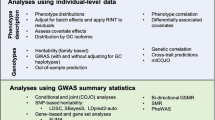

Race, Medicaid status, higher BMI at delivery and lack of prenatal vitamin use were all associated with vitamin D deficiency (25(OH)D <50 nmol l−1; P<0.01). After adjusting for Medicaid status, BMI at delivery and prenatal vitamin use, black infants had a 3.6 greater odds (95% confidence interval (CI): 2.4, 5.6) of having vitamin D deficiency compared with white infants (Table 2). Similarly, infants on Medicaid, a marker of socioeconomic status, had higher odds of vitamin D deficiency (odds ratio (OR) 2.3, 95% CI: 1.4, 3.8), whereas prenatal vitamin use showed a protective effect (OR 0.24, 95% CI: 0.09, 0.62). For every 5-unit increase in maternal BMI, infants had a 1.2 greater odds (95% CI: 1.1, 1.4) of vitamin D deficiency (Table 2). The predicted probabilities of vitamin D deficiency, based on significant predictors in the multivariable regression model, are shown in Figure 2. For instance, at a mean maternal BMI of 32.3 kg m−2, an infant who is black, on Medicaid and no prenatal vitamin use has an 86% (95% CI: 82, 97) probability of vitamin D deficiency, whereas a black infant who is not on Medicaid and with prenatal vitamin use has a 66% (95% CI: 44, 67) probability of vitamin D deficiency.

Predictive probabilities of vitamin D deficiency. Predicted probability of vitamin D deficiency (<50 nmol l−1) based on multivariable regression model including race, Medicaid status, prenatal vitamin use (PV) and body mass index (BMI) at delivery as covariates. Each curve represents the predicted probability across levels of BMI at delivery for four combinations of race, Medicaid status and PV.

Blacks had a significantly greater proportion of SGA when compared with whites (P=0.01; Table 1). As vitamin D levels also differed by race, we stratified the models predicting SGA by race and examined vitamin D deficiency, smoking, pre-eclampsia, maternal age, Medicaid status and BMI at delivery as covariates (Table 3). Black infants with vitamin D deficiency had 2.4 greater odds of SGA (95% CI: 1.0, 5.8) after adjusting for maternal history of PIH and maternal BMI, two significant confounding variables in our model (Table 3). Similarly, infants of black mothers with history of PIH were associated with 2.3 greater odds of SGA after adjustment for confounding variables. Vitamin D deficiency was not significantly associated with SGA for white infants in our study population (Table 3).

We examined several additional models with various cutpoints for 25(OH)D based on clinical guidelines and previous literature, while adjusting for maternal PIH and maternal BMI at delivery. These results indicated that black neonates with 25(OH)D levels <25 nmol l−1 had an even greater odds of being SGA (OR 3.8, 95% CI: 1.4, 10.6) compared with those with levels ⩾50 nmol l−1. The OR was 2.2 (95% CI: 0.88, 5.4) for black neonates with 25(OH)D levels 25 to 50 nmol l−1 compared with ⩾50 nmol l−1. The small proportion of neonates who were SGA with 25(OH)D levels >75 nmol l−1 precluded evaluation at higher cutpoints.

Although SGA status was the main outcome of our study, we also evaluated models of 25(OH)D and birth weight percentile after adjusting for maternal PIH and maternal BMI at delivery. Birth weight percentiles for neonates with 25(OH)D levels <25 mol l−1 were significantly lower compared with those with 25(OH)D levels ⩾50 nmol l−1 (adjusted mean weight percentile 0.35 (95% CI: 0.27, 0.43) vs 0.46 (95% CI: 0.39, 0.53), P=0.02). Mean birth weight percentile for neonates with 25(OH)D levels ⩾25 and <50 nmol l−1 was 0.39 (95% CI: 0.34, 0.45).

Discussion

In our study population, we found that compared with white infants, black infants had significantly lower cord blood vitamin D levels and a greater proportion of vitamin D deficiency. Although the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in black mothers and neonates is well known, debate exists as to the relationship between race, vitamin D deficiency and SGA.12, 14, 15, 17, 18 We examined this relationship in conjunction with additional maternal characteristics in order to identify groups of pregnant women who could benefit most from vitamin D supplementation. We found that black race was associated with a significantly greater incidence of SGA, and that black race and vitamin D deficiency together were associated with even greater odds of SGA. Based on our analysis, a minimum threshold cord blood 25(OH)D level of 50 nmol l−1 was protective against SGA status among black infants.

Interestingly however, white race with vitamin D deficiency was not significantly associated with increased odds of SGA. Only a small proportion of white infants were SGA, and this may have limited our ability to detect significant associations between vitamin D and SGA among white infants.

Vitamin D may affect fetal growth through its effect on calcium metabolism, bone growth and placental development.32 Although initial studies showed conflicting results, more recent studies suggest that vitamin D deficiency may adversely affect growth and lead to low birth weight or SGA infants.7, 9, 11, 12, 18, 22, 23, 33 Because of a known relationship between race and vitamin D status, attention then turned to investigation of the relationship between race, vitamin D deficiency and SGA. Review of published literature regarding this relationship revealed several relevant studies to ours. Bodnar et al.8 conducted a case–control study to examine the association between vitamin D levels, race and SGA. For white mothers, measurement of maternal serum 25(OH)D at <22 weeks’ gestation showed a U-shaped relationship between vitamin D status and risk of SGA, where the highest risk for SGA was seen with both low and high vitamin D levels. However, no relationship was seen between vitamin D status and SGA among black mothers. In a larger study, Burris et al.14 examined the relationship between second-trimester serum 25(OH)D levels and SGA in blacks and whites and found a higher risk of SGA in both vitamin D-deficient black and white infants. Gernand et al.22 also examined second-trimester vitamin D levels and risk of SGA in a population at risk of pre-eclampsia. They found that vitamin D status was associated with risk of SGA in white and nonobese women, but that there was no association between vitamin D and SGA in black or obese mothers.

In contrast to the above-mentioned studies, our results show that the combination of black race and vitamin D deficiency was associated with increased odds of SGA, but this relationship was not preserved for white infants. Our results may have differed for several reasons. First, the majority of populations in the studies of Bodnar et al.8 and Burris et al.14 were white, whereas the majority of our study population was black. Furthermore, this study was conducted in Hamilton County, Ohio, an area with worse perinatal outcomes than national averages, including higher infant mortality, preterm birth and low birth weight rates, as well as considerable racial disparities in infant mortality and perinatal outcomes.34 All of cord blood samples were collected over one winter season, thus negating seasonal variations in vitamin D levels that may have been seen in other studies. Finally, we analyzed cord blood vitamin D levels at the time of delivery, rather than maternal serum vitamin D levels during pregnancy. Although cord blood 25(OH)D levels do correlate to maternal levels, factors that affect fetal growth may not be uniform throughout pregnancy and this difference in timing could affect study findings.1, 3, 4, 5, 6 In addition, maternal characteristics such as obesity or pre-eclampsia could also affect results that may not have been seen if vitamin D samples were obtained during early pregnancy.

Concurrently, we also examined maternal variables known to potentially affect vitamin D levels and SGA in an effort to better understand the role of these risk factors in vitamin D levels and risk of SGA. Our results showed several factors to be significant, including BMI at delivery, pre-eclampsia, Medicaid status (as a measure of socioeconomic status) and prenatal vitamin use. Obesity is well known to be a risk factor for vitamin D deficiency because of a sequestering of vitamin D in adipose tissue.35 Maternal obesity during pregnancy has also been associated with lower vitamin D levels in neonates at delivery.24, 36, 37, 38 Our data are consistent and illustrate the inverse relationship between maternal BMI at delivery and vitamin D status after adjusting for confounding variables. The increased odds of vitamin D deficiency in neonates relative to maternal BMI level were seen in both blacks and whites in our study population and supports similar findings seen in a study done by Bodnar et al.38 Although prenatal vitamin use was not significantly different between blacks and whites in our study, prenatal vitamin use was significant among those with and without vitamin D deficiency. Furthermore, the protective effect against vitamin D deficiency was seen in both blacks and whites in our study, in contrast to a recently published study by Burris et al.,39 who found that lack of prenatal vitamin use was associated with vitamin D deficiency in white but not black women.

Importantly, our study illustrates the additive effect of maternal risk factors and their predictive probabilities for vitamin D deficiency and SGA. Black mothers on Medicaid who were obese and did not take prenatal vitamins had the highest probability of having an infant with vitamin D deficiency. Pre-eclampsia is a known independent risk factor for SGA. Pre-eclampsia, coupled with black race and vitamin D deficiency, resulted in significant increases in the predicted probability of delivering an SGA infant. Interestingly, our results show that increasing maternal BMI had a mild protective effect on risk of SGA. This corresponds to the well-known association that women with higher BMI tend to deliver infants with higher birth weights.40, 41, 42

Furthermore, identification and recognition of women and infants at high risk of vitamin D deficiency and SGA can lead to opportunities for risk modification and reduction in adverse outcomes. Specifically, this study supports a need to target supplementation strategies to mitigate the impact of adverse perinatal outcomes such as SGA. Vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy has been shown to positively affect cord blood vitamin D levels at birth.43, 44 Studies of vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy thus far have shown conflicting results with respect to birth weight and reduction of SGA.43, 45, 46, 47, 48 Adequately powered and randomized controlled trials of vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy are needed to assess the impact of supplementation on SGA as well as the appropriate dose and timing of supplementation. In addition, individuals with the risk factors that we have identified may benefit even more from supplementation or higher dose supplementation. If vitamin D supplementation does not occur during pregnancy, it may be imperative to identify and offer additional supplementation beyond the routinely recommended 400 IU per day for all infants.28

There were several limitations to our study. First, we did not have information regarding exact amounts of dietary maternal vitamin D intake and sun exposure that may affect maternal and cord blood vitamin D levels. We collected samples over one winter season to mitigate the effect of varying sun exposure. Corresponding maternal vitamin D status at different gestations during pregnancy was unknown. This would have allowed for a more expansive definition of the relationship between maternal vitamin D status and perinatal outcomes. Finally, as a retrospective study, we were limited by available data and the amount of cord blood available for further testing.

Conclusion

Black obese mothers on Medicaid without prenatal vitamin use were at the highest risk of delivering neonates with vitamin D deficiency. Furthermore, black race and vitamin D deficiency were associated with an increased risk of SGA. We identified additive and modifiable maternal risk factors that would benefit most from risk reduction and targeted vitamin D supplementation. A greater understanding of the variables that influence vitamin D status during pregnancy can have an immense public health impact in the reduction of adverse perinatal outcomes such as SGA.

References

Cadario F, Savastio S, Pozzi E, Capelli A, Dondi E, Gatto M et al. Vitamin D status in cord blood and newborns: ethnic differences. Ital J Pediatr 2013; 39: 35.

Dawodu A, Tsang RC . Maternal vitamin D status: effect on milk vitamin D content and vitamin D status of breastfeeding infants. Adv Nutr 2012; 3 (3): 353–361.

Hollist BW, Pittard WB III . Evaluation of the total fetomaternal vitamin D relationships at term: evidence for racial differences. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1984; 59 (4): 652–657.

Kaludjerovic J, Vieth R . Relationship between vitamin D during perinatal development and health. J Midwifery Womens Health 2010; 55 (6): 550–560.

Pena HR, de Lima MC, Brandt KG, de Antunes MM, da Silva GA . Influence of preeclampsia and gestational obesity in maternal and newborn levels of vitamin D. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015; 15 (1): 112.

Marshall I, Mehta R, Petrova A . Vitamin D in the maternal-fetal-neonatal interface: clinical implications and requirements for supplementation. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2013; 26 (7): 633–638.

Chen Y, Fu L, Hao J, Yu Z, Zhu P, Wang H et al. Maternal vitamin D deficiency during pregnancy elevates the risks of small for gestational age and low birth weight infants in Chinese population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015; 100 (5): 1912–1919.

Bodnar LM, Catov JM, Zmuda JM, Cooper ME, Parrott MS, Roberts JM et al. Maternal serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations are associated with small-for-gestational age births in white women. J Nutr 2010; 140 (5): 999–1006.

Leffelaar ER, Vrijkotte TG, van Eijsden M . Maternal early pregnancy vitamin D status in relation to fetal and neonatal growth: results of the multi-ethnic Amsterdam born children and their development cohort. Br J Nutr 2010; 104 (01): 108–117.

Bodnar LM, Simhan HN, Powers RW, Frank MP, Cooperstein E, Roberts JM . High prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency in black and white pregnant women residing in the northern United States and their neonates. J Nutr 2007; 137 (2): 447–452.

Wei S, Qi H, Luo Z, Fraser WD . Maternal vitamin D status and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2013; 26 (9): 889–899.

Aghajafari F, Nagulesapillai T, Ronksley PE, Tough SC, O'Beirne M, Rabi DM . Association between maternal serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and pregnancy and neonatal outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ 2013; 346: f1169.

Lapillonne A . Vitamin D deficiency during pregnancy may impair maternal and fetal outcomes. Med Hypotheses 2010; 74 (1): 71–75.

Burris HH, Rifas-Shiman SL, Camargo CA, Litonjua AA, Huh SY, Rich-Edwards JW et al. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D during pregnancy and small-for-gestational age in black and white infants. Ann Epidemiol 2012; 22 (8): 581–586.

Bodnar LM, Simhan HN . Vitamin D may be a link to black-white disparities in adverse birth outcomes. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2010; 65 (4): 273–284.

Ginde AA, Sullivan AF, Mansbach JM, Camargo CA . Vitamin D insufficiency in pregnant and nonpregnant women of childbearing age in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 2010; 202 (5): 436.e1–436.e8.

Hamilton SA, McNeil R, Hollis BW, Davis DJ, Winkler J, Cook C et al. Profound vitamin D deficiency in a diverse group of women during pregnancy living in a sun-rich environment at latitude 32 degrees N. Int J Endocrinol 2010; 2010: 917428.

Eichholzer M, Platz EA, Bienstock JL, Monsegue D, Akereyeni F, Hollis BW et al. Racial variation in vitamin D cord blood concentration in white and black male neonates. Cancer Causes Control 2013; 24 (1): 91–98.

Johnson DD, Wagner CL, Hulsey TC, McNeil RB, Ebeling M, Hollis BW . Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency is common during pregnancy. Am J Perinatol 2011; 28 (1): 7–12.

Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, Osterman MJ, Wilson EC, Mathews T . Births: Final data for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2012; 61 (1): 1–72.

MacDorman MF . Race and ethnic disparities in fetal mortality, preterm birth, and infant mortality in the United States: an overview. Semin Perinatol 2011; 35 (4): 200–208.

Gernand AD, Simhan HN, Caritis S, Bodnar LM . Maternal vitamin D status and small-for-gestational-age offspring in women at high risk for preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol 2014; 123 (1): 40–48.

Mirzaei F, Amiri Moghadam T, Arasteh P . Comparison of serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels between mothers with small for gestational age and appropriate for gestational age newborns in kerman. Iran J Reprod Med 2015; 13 (4): 203–208.

Josefson JL, Feinglass J, Rademaker AW, Metzger BE, Zeiss DM, Price HE et al. Maternal obesity and vitamin D sufficiency are associated with cord blood vitamin D insufficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 98 (1): 114–119.

Fenton TR, Kim JH . A systematic review and meta-analysis to revise the Fenton growth chart for preterm infants. BMC Pediatr 2013; 13: 59–2431-13-59.

Onis M . WHO child growth standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta Paediatr 2006; 95 (S450): 76–85.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG . Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42 (2): 377–381.

Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, Aloia JF, Brannon PM, Clinton SK et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96 (1): 53–58.

Lips P . Which circulating level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D is appropriate? J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2004; 89: 611–614.

Holick MF . Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med 2007; 357 (3): 266–281.

Holmes VA, Barnes MS, Alexander HD, McFaul P, Wallace JM . Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency in pregnant women: a longitudinal study. Br J Nutr 2009; 102 (06): 876–881.

Shin JS, Choi MY, Longtine MS, Nelson DM . Vitamin D effects on pregnancy and the placenta. Placenta 2010; 31 (12): 1027–1034.

Rodriguez A, García‐Esteban R, Basterretxea M, Lertxundi A, Rodriguez-Bernal C, Iniguez C et al. Associations of maternal circulating 25‐hydroxyvitamin D3 concentration with pregnancy and birth outcomes. BJOG 2014; 122: 1695–1704.

Carlson D, Bush D, Besl J . Maternal and infant health monthly surveillance report. 2012; http://www.hamiltoncountyhealth.org/files/files/Reports/September_2012_IM_Report.pdf.

Wortsman J, Matsuoka LY, Chen TC, Lu Z, Holick MF . Decreased bioavailability of vitamin D in obesity. Am J Clin Nutr 2000; 72 (3): 690–693.

Ozias MK, Scholtz SA, Kerling EH, Atwood DN, Carlson SE . BMI, race, supplementation, season, and gestation affect vitamin D status in pregnancy in kansas city (latitude 39 {degrees} N). FASEB J 2012; 26 (1_MeetingAbstracts): lb393.

Scholl TO, Chen X . Vitamin D intake during pregnancy: association with maternal characteristics and infant birth weight. Early Hum Dev 2009; 85 (4): 231–234.

Bodnar LM, Catov JM, Roberts JM, Simhan HN . Prepregnancy obesity predicts poor vitamin D status in mothers and their neonates. J Nutr 2007; 137 (11): 2437–2442.

Burris H, Thomas A, Zera C, McElrath T . Prenatal vitamin use and vitamin D status during pregnancy, differences by race and overweight status. J Perinatol 2014; 35: 241–15.

Cedergren M . Effects of gestational weight gain and body mass index on obstetric outcome in Sweden. Int J Gynecol Obstetr 2006; 93 (3): 269–274.

Siega-Riz AM, Viswanathan M, Moos M, Deierlein A, Mumford S, Knaack J et al. A systematic review of outcomes of maternal weight gain according to the Institute of Medicine recommendations: birthweight, fetal growth, and postpartum weight retention. Obstet Gynecol 2009; 201 (4): 339.e1–339.e14.

Sebire NJ, Jolly M, Harris JP, Wadsworth J, Joffe M, Beard RW et al. Maternal obesity and pregnancy outcome: a study of 287,213 pregnancies in London. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001; 25 (8): 1175–1182.

Nandal R, Chhabra R, Sharma D, Lallar M, Rathee U, Maheshwari P . Comparison of cord blood vitamin D levels in newborns of vitamin D supplemented and unsuppplemented pregnant women: a prospective, comparative study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2016; 29 (11): 1812–1816.

Yang N, Wang L, Li Z, Chen S, Li N, Ye R . Effects of vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy on neonatal vitamin D and calcium concentrations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Res 2015; 35: 547–556.

Pérez-López FR, Pasupuleti V, Mezones-Holguin E, Benites-Zapata VA, Thota P, Deshpande A et al. Effect of vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Fertil Steril 2015; 103 (5): 1278–1288.e4.

Wei SQ . Vitamin D and pregnancy outcomes. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2014; 26 (6): 438–447.

Marya R, Rathee S, Dua V, Sangwan K . Effect of vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy on foetal growth. Indian J Med Res 1988; 88: 488–492.

Brooke OG, Brown IR, Bone CD, Carter ND, Cleeve HJ, Maxwell JD et al. Vitamin D supplements in pregnant Asian women: effects on calcium status and fetal growth. Br Med J 1980; 280 (6216): 751–754.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Center for Clinical & Translational Science & Training (CCTST) at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center/University of Cincinnati for their support and assistance in performing the vitamin D assays, as well as REDCap for use of an electronic storage database.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Seto, T., Tabangin, M., Langdon, G. et al. Racial disparities in cord blood vitamin D levels and its association with small-for-gestational-age infants. J Perinatol 36, 623–628 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2016.64

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2016.64

This article is cited by

-

Reference values of fetal ultrasound biometry: results of a prospective cohort study in Lithuania

Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics (2022)

-

Vitamin D status during pregnancy and offspring outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2020)

-

Relationship between vitamin D status and the vaginal microbiome during pregnancy

Journal of Perinatology (2019)