Abstract

Recently, the SOX2 gene has been reported to be amplified in human lung squamous cell carcinomas. However, its roles in human lung adenocarcinomas are still elusive. In this study, we analyzed the functions of SOX2 in cancer stem-like cells (CSCs)/cancer-initiating cells (CICs) derived from human lung adenocarcinoma. Human lung CSCs/CICs were isolated as higher tumorigenic side population (SP) cells using Hoechst 33342 dye from several lung cancer cell lines. Four of nine lung cancer cell lines were positive for SP cells (LHK2, 1-87, A549, Lc817). The ratios of SP cells ranged from 0.4% for Lc817 to 2.8% for LHK2. To analyze the molecular aspects of SP cells, we performed microarray screening and RT-PCR analysis, and isolated SOX2 as one of a SP cell-specific gene. SOX2 was expressed predominantly in LHK2 and 1-87 SP cells, and was also expressed in several other cancer cell lines. The expression of SOX2 protein in primary human lung cancer tissues were also confirmed by immunohistochemical staining, and SOX2 was detected in more than 80% of primary lung cancer tissues. To address SOX2 molecular functions, we established a SOX2-overexpressed LHK2 and A549 cell line (LHK2-SOX2 and A549-SOX2). LHK2-SOX2 cells showed higher rates of SP cells and higher expression of POU5F1 compared with control cells. LHK2-SOX2 and A549-SOX2 cells showed relatively higher tumorigenicity than control cells. On the other hand, SOX2 mRNA knockdown of LHK2 SP cells by gene-specific siRNA completely abrogated tumorigenicity in vivo. These observations indicate that SOX2 has a role in maintenance of stemness and tumorigenicity of human lung adenocarcinoma CSCs/CICs and is a potential target for treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Despite the recent progress of treatments, survival rates of cancer patients remain still low, especially in advanced cases. Recurrence of the disease, tolerance to treatment and distant metastasis make the disease untreatable. Therefore, to improve the treatment of those cancer patients, further molecular mechanisms related to recurrence, tolerance to treatment and distant metastasis are essential.

Recently, cancer stem-like cells (CSCs)/cancer-initiating cells (CICs) have been described as small populations that have (i) higher tumorigenicity, (ii) differentiation ability and (iii) self-renewal ability.1 As CSCs/CICs have these characteristics they are thought to be related to cancer recurrence after treatment and distant metastasis. And, recently CSCs/CICs have been proved to be related to resistance to treatments. Therefore, elimination of CSCs/CICs are essential for cancer treatment.1

CSC/CIC was first described in hematopoietic malignancies,2 and it was also described in epithelial malignancies in the following works.3 At this time, there are no definitive markers of CSCs/CICs; however, three major methods for enriching CSC/CIC population have been described.4 One is side population (SP) cells based on the efflux of Hoechst 33342 dye.5 CSCs/CICs were successfully isolated as SP cells in several types of cancers.6, 7, 8, 9 The second method is cell surface markers. CD44+CD24−/low for breast CSCs/CICs3 and CD133 for glioma CSCs/CICs10 and several other cell surface markers were reported for isolation of a CSC/CIC population. We also previously reported that CD44 is a tumor-initiating cell marker candidate.11 The third is ALDEFLUOR assay based on the expression of aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) enzyme activity.12

Despite the differences in isolation methods, these CSCs/CICs have been described to have higher tumorigenicity than that of non-CSCs/CICs. Higher tumorigenicity is the fundamental phenotype of CSCs/CICs and it makes CSCs/CICs a reasonable target for cancer therapy. However, the molecular mechanisms related to the tumorigenicity are still elusive.

In this study, we analyzed the molecular mechanisms of the tumorigenicity of lung CSCs/CICs isolated as SP cells, and found that SOX2 was one of the SP-specific genes. SOX2 is related to the maintenance of stem cell phenotype including SP cells, expression of POU5F1 and tumorigenicity of lung adenocarcinoma cells. These observations indicate that SOX2 is a potential target of lung adenocarcinoma CSCs/CICs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Lines

Lung adenocarcinoma cell lines LHK2 and LNY-1 were established in our laboratory.13 Lung squamous cell carcinoma cell lines Sq-1 and Sq-19, adenocarcinoma cell lines 1-87 and 11-18, large cell carcinoma cell lines 86-2 and Lu99, and small cell carcinoma cell lines Lu65, S2 and LK79 were obtained from the Cell Resource Center for Biomedical Research, Tohoku University (Sendai, Japan). Lung small cell carcinoma cell line Lc817 was purchased from the Japanese Cancer Research Resources Bank. Lung adenocarcinoma cell line A549, renal cell carcinoma lines ACHN and Caki-1, prostate carcinoma cell line DU145 and cervical carcinoma cell line HeLa were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Renal cell carcinoma line SMKT-R1 was a kind gift from Dr T Tsukamoto (Sapporo, Japan). All of these cancer cells were cultured in DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA, USA) at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. The retrovirus packaging cell line PLAT-A was kindly provided by Dr T Kitamura (Tokyo, Japan). PLAT-A was maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 1 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich) and 10 μg/ml blasticidin (Sigma-Aldrich).

SP Analysis

Side population (SP) cells were isolated as described previously using Hoechst 33342 dye (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) with some modifications.5 Briefly, cells were resuspended at 1 × 106/ml in pre-warmed DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS. Hoechst 33342 dye was added at a final concentration of 5 μg/ml in the presence or absence of verapamil (75 μM; Sigma-Aldrich) and the cells were incubated at 37 °C for 90 min with intermittent shaking. For isolation of SP cells from 1-87 cells Hoechst 33342 dye was used at concentration of 1 μg/ml. Analyses and sorting were performed with a FACSAria II cell sorter (Becton Dickinson).

RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription-PCR Analysis

RT-PCR analysis was performed as described previously.14 Total RNA (tRNA) was isolated from cultured cells by an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) using DNase (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA was synthesized using Superscript III and oligo (dT) primer (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Human Multiple Tissue cDNA Panels I and II (Clontech) and the Human Fetal Multiple Tissue cDNA Panel (Clontech) were used as templates of normal adult and fetal tissue cDNAs. PCR amplification was performed with PrimeSTAR HS DNA polymerase (Takara Biotechnology, Japan). The PCR mixture was initially incubated at 98 °C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 15 s, and annealing and extension at 68 °C for 30 s. Primer pairs used for RT-PCR analysis were 5′-CATGATGGAGACGGAGCTGA-3′ and 5′-ACCCCGCTCGCCATGCTATT-3′ for SOX2 with an expected PCR product size of 410 bp, 5′-TGGAGAAGGAGAAGCTGGAGCAAAA-3′ and 5′-GGCAGATGGTCGTTTGGCTGAATA-3′ for POU5F1 with an expected PCR product size of 163 bp and 5′-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3′ and 5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3′ for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) with an expected product size of 452 bp. GAPDH was used as an internal control.

Immunohistochemical Staining of Tissue Sections

Immunohistochememical staining was done with formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections of 67 primary lung carcinoma tissues (21 squamous cell carcinomas, 40 adenocarcinomas, 4 small cell carcinomas and 2 large cell carcinomas). Antigen retrieval was done by boiling sections in 120 °C for 5 min in a microwave oven in preheated 0.01 mol/l sodium citrate (pH 6.0). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by 3% hydrogen peroxide in ethanol for 10 min. After blocking with 1% non-fat dry milk in PBS (pH 7.4), the sections were reacted with plyclonal anti-SOX2 antibody (Invitrogen) for 1 h followed by incubation with biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (Nichirei) for 30 min. Subsequently, the sections were stained with streptavidin-biotin complex (Nichirei), followed by incubation with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine used as the chromogen and counterstaining with hematoxylin. Nuclear staining was considered positive. We graded the immunoreactivity as follows: 0, less than 1% positive rates; 1+, 1–10% positive rates; 2+, more than 10% positive rates.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Primers and probes were designed by the manufacturer (TaqMan Gene expression assays; Applied Biosystems). Thermal cycling was performed using 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s followed by 60 °C for 1 min. Each experiment was done in triplicate and normalized to the GAPDH gene as an internal control.

Generation of a Stable Cell Line Overexpressing SOX2

Transduction of SOX2 DNA into LHK2 and A549 cells was performed by a retrovirus-mediated method.15 Briefly, FLAG-tagged SOX2, cloned from LHK2 cDNA by RT-PCR was inserted into the pMXs-puro retrovirus vector (a kind gift from Dr T Kitamura). Retrovirus infection was performed as described previously.15 Two days after infection, 1 μg/ml puromycin was added to the medium to select a stably transduced subline. The expression of SOX2 was confirmed by western blots.

Cell Cycle Analysis

After the cells has been fixed with 70% ethanol, they were resuspended in PBS containing 250 μg/ml RNase A (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at 37 °C and stained with 50 μg/ml propidium iodide for 10 min at 4 °C in the dark. Stained cells were analyzed with a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson), and the data were analyzed using the Mod-Fit cell cycle analysis program.

Xenograft Transplantation

In vivo experiments were done in accordance with the institutional guidelines for the use of laboratory animals. Various numbers of SP and main population (MP) cells ranging from 15 to 1.5 × 104 and SOX2-overexpressing and mock-transfected cells ranging from 10 to 1 × 104 were suspended in 200 μl of 1:1 PBS/Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA) and injected into the subcutaneous space in the back in female non-obese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD/SCID) mice (Sankyo Laboratory (Tsukuba, Japan)) (6 to 8 weeks old) under anesthesia. For xenograft transplantation with LHK2 SP cells transfected with SOX2 siRNA, 1 × 102 cells were used for injection.

SOX2 mRNA Knockdown by siRNA

A SOX2 gene knockdown experiment was performed using small interfering RNA (siRNA). SOX2 siRNA duplex was designed and synthesized using the BLOCK-it RNAi designer system (Invitrogen). The oligonucleotide encoding SOX2 siRNA1 was 5′-CCUCCGGGACAUGAUCAGCAUGUAU-3′. Negative control siRNA was obtained from Invitrogen. LHK2 SP cells were seeded into a 24-well plate, and transfections were carried out using Lipofectamine RNAi max (Invitrogen) in Opti-MEM according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical Analysis

Student's t test was used to compare two groups. P<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Detection of CSCs/CICs as SP Cells in Human Lung Carcinoma Cell Lines

To obtain lung CSCs/CICs, we screened nine human lung carcinoma cell lines (LHK2, A549, Lc817, Sq-1, 1-87, Lu99, 86-2, LK79 and S2) by SP analysis and isolated SP cells in four lines (LHK2, 1-87, A549 and Lc817) (Figure 1a). The ratios of SP cells ranged from 0.4% for Lc817 cells to 2.8% for LHK2 cells. SP cells completely disappeared in the presence of verapamil, an ABC-transporter inhibitor, indicating that these SP cells were specific for efflux of Hoechst 33342 dye by an ABC transporter. We could isolate SP cells from LHK2 cells stably and therefore used LHK2 cells in the following experiments.

Isolation of lung CSCs/CICs as SP cells. (a) Isolation of SP cells in lung carcinoma cells. Lung carcinoma cell lines were stained with Hoechst 33342 dye in the absence (upper panel) or presence (lower panel) of verapamil. Adenocarcinoma cell lines (LHK2, 1-87 and A549) and a small cell carcinoma cell line (Lc817) were analyzed by a cell sorter. (b) Tumor growth of LHK2 SP cells and MP cells; 1.5 × 102 LHK2 SP cells and MP cells were injected into the backs of NOD/SCID mice. (c) Representative tumors of SP and MP cells; 1.5 × 102 SP and MP cells derived from LHK2 were injected into the backs (left: SP cells, right: MP cells) of NOD/SCID mice. (d) Histology of SP cell-derived and MP cell-derived tumors. Tumors derived from LHK2 SP cells and LHK2 MP cells were stained by hematoxylin and eosin. Magnification × 200.

To address the tumorigenicity of LHK2 SP cells, serial diluted SP and MP cells derived from LHK2 cells were inoculated into non-obese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mice. As shown in Table 1, Figures 1b and c, a tumor could be initiated by 1.5 × 103 (100%), 1.5 × 102 (100%) and even 1.5 × 101 LHK2 SP cells (two of five mice). On the other hand, a tumor could be initiated by 1.5 × 103 (3 of 5 mouse) and 1.5 × 104 LHK2 MP cells but not by 1.5 × 101 and 1.5 × 102 LHK2 MP cells. These results suggest that LHK2 SP cells have about 100 times more efficient tumorigenicity than that of LHK2 MP cells.

We evaluated the histology of both LHK2 SP cell-derived and LHK2 MP cell-derived tumors. As shown in Figure 1d, the histology of both SP tumor and MP tumors showed similar poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. These observations suggest that LHK2 SP cells contain higher rates of CSC/CIC than LHK2 MP cells; however, the rates of CSC/CIC do not affect the pathological grades.

SOX2 Expression in SP Cells

To analyze the molecular mechanism of tumorigenicity in SP cells, we performed gene chip microarray screening (Sigma Genosys, Ishikari, Japan) using total RNA from LHK2 SP cells and LHK2 MP cells. We found that SOX1 gene oligo reactive mRNA was overexpressed in LHK2 SP cells compared with the expression level in LHK2 MP cells. SOX1 is one of the B1 SOX genes along with SOX2 and SOX3.16 Group B1 sox genes encode high mobility group (HMG) domain transcription factors that have major roles in neural development.17 SOX1, SOX2 and SOX3 share highly homologous sequence, and SOX1 oligo on the gene chip we used in this study completely shares DNA sequence with SOX2 and SOX3. Thus we evaluated three mRNA transcripts by quantitative real-time PCR. As shown in Figure 2a, SOX2 mRNA was significantly overexpressed (5.2-fold) in SP cells compared with the level in MP cells (Figure 1c); however, SOX1 and SOX3 were not detectable in either SP cells or MP cells (data not shown). This suggests that SOX2 cDNA was screened out by microarray screening, and we performed further analysis of SOX2. SOX2 mRNA was also overexpressed in another lung adenocarcinoma cell line (1-87) (Figure 2a).

Expression of SOX2. (a) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of SOX2 mRNA expression in SP and MP cells. MP cells were used for the control, which was set as 1.0. Data are expressed as means±s.d. of relative values compared with MP cells. (b) RT-PCR using human cancer cells. Fetal brain was used as a positive control. Double distilled water (DDW) was used as a negative control. (c) RT-PCR using human adult tissues and human fetal tissues.

Expression of SOX2 in Normal Tissues and Cancer Cells

RT-PCR analysis was performed to evaluate the expression of SOX2 in human fetal and adult normal tissues and cancer cells. As shown in Figure 2b, SOX2 mRNA was expressed in the brain at a high level and in the lung at a low level in human fetal tissues. In human adult tissues, SOX2 was detected in the brain, lung, pancreas, prostate, testis, small intestine and stomach at low levels. Cancer cells were also evaluated (Figure 2d), and SOX2 mRNA was detected in all cells tested in this study including lung squamous cell carcinoma cells (Sq-1 and Sq-19), lung adenocarcinoma cells (LNY1, A549, LHK2, 1-87 and 1-18), lung large cell carcinoma cells (Lu99 and 86-2), lung small cell carcinoma cells (S2, Lu65, Lc817 and LK79), cervical carcinoma cells (HeLa), renal cell carcinoma cells (ACHN, Caki-1 and SMKT-R1) and prostate carcinoma cells (DU145).

Expression of SOX2 Protein in Lung Carcinoma Tissues

Immunohistochemical staining using an anti-SOX2 protein polyclonal antibody was performed to evaluate the expression of SOX2 protein in primary lung carcinoma tissues. A total of 67 primary lung carcinoma tissues (21 squamous cell carcinomas, 40 adenocarcinomas, 4 small cell carcinomas and 2 large cell carcinomas) were evaluated by a semi-quantitative scale as follows: 0, less than 1% positive rates; 1+, 1–10% positive rates; 2+, more than 10% positive rates. Representative immunohistochemical staining is shown in Figure 3a. As shown in Figure 3b, SOX2 was positive in 86% of squamous cell carcinomas (2+: 33%, 1+: 53%, n=21), 83% of adenocarcinomas (2+: 45%, 1+: 38%, n=40), 50% of small cell carcinomas (1+: 50%, n=4) and 100% of large cell carcinomas (1+: 100%, n=2).

Immunohistochemical staining of lung cancer tissues. (a) Representative immunohistochemical staining of SOX2. SOX2 protein was stained by a polyclonal antibody. Positive rates of SOX2 were evaluated by a semi-quantitative scale as follows: 0, less than 1% positive rates; 1+, 1–10% positive rates; 2+, more than 10% positive rates. Magnification × 100. (b) Immunohistochemical staining of lung cancer tissues.

SOX2 do not Affect Cell Growth In Vitro but Is Related to Stem-Cell Phenotype and Enhanced Tumorigenicity In Vivo

To assess the functions of SOX2 in lung cancer cells, we established a SOX2-overexpressing subline of LHK2 (LHK2-SOX2). FLAG-tagged SOX2 protein expression was confirmed by western blotting (Figure 4a). In vitro cell proliferation assay and cell cycle analysis were performed using LHK2-SOX2 and Mock transformant (LHK2-Mock) cells. As shown in Figures 4b and c, there was no significant difference in cell growth or cell cycle between LHK2-SOX2 and LHK2-Mock cells. The rate of SP cells was increased in SOX2-overexpressed cells (Figure 4d). The expression of POU5F1, one of the stem cell markers, was increased in SOX2-overexpressed cells (Figure 4e).

Overexpression of SOX2. (a) Expression of SOX2 protein in LHK2-SOX2 confirmed by western blotting with an anti-FLAG antibody. (b) Cell proliferation assay of LHK2-SOX2 and LHK2-Mock in vitro. (c) Cell cycle analysis of LHK2-SOX2 and LHK2-Mock. (d) SP cells in SOX2-overexpressed cells. LHK2-Mock cells and LHK2-SOX2 cells were analyzed with SP assay. The ratios of SP cells were 1.4% for LHK2-Mock cells and 3.1% for LHK2-SOX2 cells, respectively. (e) RT-PCR using LHK2-Mock and LHK2-SOX2 cells. SOX2 and POU5F1 expression were addressed with RT-PCR. GAPDH was used as an internal control. (f) Tumors derived from LHK2-SOX2 and LHK2-Mock cells. Arrow and arrowhead show the injected areas of LHK2-SOX2 and LHK2-mock, respectively. (g) Tumor growth of SOX2-overexpressed cells in vivo; 1 × 104 of SOX2 or Mock vector transduced LHK2 and A549 cells were injected into NOD/SCID mice subcutaneously. Asterisks represent statistically significant difference compared with LHK2-Mock. P<0.05. Data represent mean±s.d.

The tumorigenicity of LHK2-SOX2 cells in vivo was addressed using NOD/SCID mice. Serially diluted LHK2-SOX2 cells and LHK2-Mock cells were injected into the backs of mice. As shown in Table 2, tumors could be observed in one of four mice inoculated with 1 × 102 LHK2-SOX2 cells, and tumors were initiated in three of four mice and in four of four mice inoculated with 1 × 103 and 1 × 104 LHK2-SOX2 cells, respectively. On the other hand, a tumor was initiated in the mice inoculated with 1 × 104 LHK2-Mock cells, but not in the mice inoculated with 1 × 102 and 1 × 103 LHK2-Mock cells. Furthermore, tumor growth speed was significantly enhanced with LHK2-SOX2 cells (Figures 4f and g). The tumorigenicity of SOX2-overexpressed A549 cells also tends to be higher compared with Mock-transduced A549 cells.

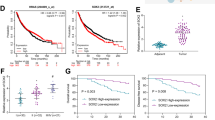

Downregulation of SOX2 by siRNA Abrogated Tumorigenicity of SP Cells

To confirm the effect of SOX2 on tumorigenicity, we performed a SOX2 gene-knockdown study using siRNA. As SOX2 was preferentially expressed in SP cells, we transfected SOX2 siRNA into LHK2 SP cells. As shown in Figure 5, 2 days after siRNA transfection, RT-PCR showed that SOX2 mRNA was reduced compared with that in control siRNA-transfected LHK2 SP cells. To evaluate the role of SOX2 in tumorigenicity, 1 × 102 siRNA-transfected LHK2 SP cells were inoculated into the backs of NOD/SCID mice. As shown in Figure 5, control siRNA-transfected LHK2 SP cells initiated a tumor 9 weeks after injection (four of four mice), and the tumor grew week by week. On the other hand, SOX2 siRNA-transfected LHK2 SP cells did not initiate a tumor even 14 weeks after injection (n=4). These results suggest that SOX2 has a pivotal role in the tumorigenicity in SP cells.

SOX2 knockdown of LHK2 SP cells by siRNA. LHK2 SP cells were isolated and seeded into a 24-well plate. SOX2 siRNA was transfected into LHK2 SP cells. The expression of SOX2 was evaluated by RT-PCR. Two days after transfection, LHK2 SP cells were injected into NOD/SCID mice. Asterisks represent statistically significant difference compared with control siRNA transfected LHK2 SP cells. P<0.05.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we isolated and analyzed lung CSCs/CICs. In the previous study, Ho et al8 described that lung CSCs/CICs could be isolated as SP cells. The authors isolated SP cells from all tested cell lines including lung adenocarcinoma cell lines (A549, H23 and H441), a large cell carcinoma cell line (H460) and squamous cell carcinoma cell lines (HTB-58 and H2170), and the ratios of SP cells ranged from 1.5% (H23) to 6.1% (H441). The other group also described hat CSCs/CICs could be isolated as SP cells from lung small cell carcinoma cell lines.18 In this study, we examined lung adenocarcinoma cell lines (LHK2, A549, 1-87), small cell carcinoma cell lines (Lc817, LK79 and S2), a squamous cell carcinoma cell line (Sq-1) and large cell carcinoma cell lines (Lu99 and 86-2), and SP cells could be isolated only from adenocarcinoma cell lines (LHK2, 1-87 and A549) and a small cell carcinoma cell line (Lc817). Our protocol for isolation of SP cells was similar to that of Ho et al;8 however, we could not isolate SP cells from large cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinoma.

As, SP fraction depends on the activity of ABCG2,19 the difference between our results and the results obtained by Ho et al8 might be due to the differences in conditions of the cells, the cell lines used for assay and cell sorters used for isolating SP cells. Lung CSCs/CICs have also been isolated by other methods such as the ALDEFLUOR assay20 and the use of cell surface markers such as CD133.21 These lung CSCs/CICs share the common phenotype of higher tumorigenicity than that of non-CSCs/CICs, and these CSCs/CICs derived from lung cancers are suitable for further analysis of lung CSCs/CICs.

The SOX family consists of transcription factors containing a HMG of DNA-binding domains that is expressed in a wide variety of tissues and has important roles in the regulation of organ development and cell-type specification. SOX2 is expressed in embryonic stem (ES) cells, neural stem cells and normally differentiated gastric epithelial cells, suggesting that it has various functions. In neural stem cells, SOX2 acts with SOX1 and SOX3 to maintain the self-renewal of cells.22 Li et al23 reported that SOX2 was expressed in normal gastric epithelial cells and induced the expression of MUC5AC, suggesting that SOX2 induces cell differentiation in the stomach. Masui et al24 reported that Sox2 was indispensable for maintaining ES cell pluripotency and that Sox2 regulates Oct3/4 expression by regulating expressions of several upstream transcription factors.

SOX2 has been reported to be upregulated in several kinds of malignancies, including lung carcinoma,25 gastric carcinoma,23 basal type breast carcinoma26 and gliomas.27 Chen et al28 first described the functions of SOX2 in breast carcinoma cells. The authors reported that SOX2 associates with β-catenin and induces CCND1 gene expression and enhances cell growth both in vitro and in vivo. In this study, overexpression of SOX2 enhanced tumorigenicity in vivo; however, it did not affect cell growth in vitro. Overexpression of SOX2 did not affect cell cycle status in vitro, thus SOX2 might not be related to expression of the CCND1 gene in lung adenocarcinoma cells.

Gangemi et al29 reported that knockdown of SOX2 mRNA of glioma cells stopped cell growth and caused loss of tumorigenicity in immune-deficient mice. In this study, transient knockdown of SOX2 mRNA by SOX2-specific siRNA completely abrogated the tumorigenicity of SP cells. These observations indicate that SOX2 has a role in tumorigenicity of both gliomas and lung adenocarcinomas in vivo; however, its exact molecular mechanisms are still elusive.

SOX2 has been described to be overexpressed in lung squamous cell carcinomas30, 31, 32 and has a role as an oncogene. Its role in tumorigenicity was confirmed in a mouse transgenic model.33 However, there are no reports on SOX2 and lung adenocarcinoma tumorigenicity. Recently, Sholl et al34 described that SOX2 protein expression in early-stage lung adenocarcinoma tissues was related to shorter time to progression and shorter overall survival. These findings support the notion that SOX2 is related to CSCs/CICs and tumorigenicity and SOX2 may be a target of lung adenocarcinoma CSCs/CICs. In this study, transient transfection of SOX2 siRNA completely abrogated the tumorigenicity of LHK2 SP cells. The effects of siRNA should be transient, lasting only about 1 week, but the tumorigenicity was completely inhibited even 14 weeks after injection of the cells. This data indicate that the SOX2 knockdown effect was irreversible in CSCs/CICs. Therefore, transient inhibition might be sufficient to inhibit tumorigenicity of lung adenocarcinoma CSCs/CICs.

In summary, SOX2 is related to the tumorigenicity of lung adenocarcinoma CSCs/CICs in vivo. Further molecular analysis especially upstream and downstream of SOX2 should reveal the mechanisms of tumorigenicity. SOX2 might be molecular target of lung adenocarcinomas.

References

Visvader JE, Lindeman GJ . Cancer stem cells in solid tumours: accumulating evidence and unresolved questions. Nat Rev Cancer 2008;8:755–768.

Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, et al. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature 1994;367:645–648.

Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, et al. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003;100:3983–3988.

Hirohashi Y, Torigoe T, Inoda S, et al. Immune response against tumor antigens expressed on human cancer stem-like cells/tumor-initiating cells. Immunotherapy 2010;2:201–211.

Goodell MA, Brose K, Paradis G, et al. Isolation and functional properties of murine hematopoietic stem cells that are replicating in vivo. J Exp Med 1996;183:1797–1806.

Kondo T, Setoguchi T, Taga T . Persistence of a small subpopulation of cancer stem-like cells in the C6 glioma cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:781–786.

Chiba T, Kita K, Zheng YW, et al. Side population purified from hepatocellular carcinoma cells harbors cancer stem cell-like properties. Hepatology 2006;44:240–251.

Ho MM, Ng AV, Lam S, et al. Side population in human lung cancer cell lines and tumors is enriched with stem-like cancer cells. Cancer Res 2007;67:4827–4833.

Murase M, Kano M, Tsukahara T, et al. Side population cells have the characteristics of cancer stem-like cells/cancer-initiating cells in bone sarcomas. Br J Cancer 2009;101:1425–1432.

Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clarke ID, et al. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature 2004;432:396–401.

Kanki K, Torigoe T, Hirai I, et al. Molecular cloning of rat NK target structure—the possibility of CD44 involvement in NK cell-mediated lysis. Microbiol Immunol 2000;44:1051–1061.

Ginestier C, Hur MH, Charafe-Jauffret E, et al. ALDH1 is a marker of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells and a predictor of poor clinical outcome. Cell Stem Cell 2007;1:555–567.

Hirohashi Y, Torigoe T, Hirai I, et al. Establishment of shared antigen reactive cytotoxic T lymphocyte using co-stimulatory molecule introduced autologous cancer cells. Exp Mol Pathol 2010;88:128–132.

Nakatsugawa M, Hirohashi Y, Torigoe T, et al. Novel spliced form of a lens protein as a novel lung cancer antigen, Lengsin splicing variant 4. Cancer Sci 2009;100:1485–1493.

Morita S, Kojima T, Kitamura T . Plat-E: an efficient and stable system for transient packaging of retroviruses. Gene Ther 2000;7:1063–1066.

Schepers GE, Teasdale RD, Koopman P . Twenty pairs of sox: extent, homology, and nomenclature of the mouse and human sox transcription factor gene families. Dev Cell 2002;3:167–170.

Okuda Y, Yoda H, Uchikawa M, et al. Comparative genomic and expression analysis of group B1 sox genes in zebrafish indicates their diversification during vertebrate evolution. Dev Dyn 2006;235:811–825.

Salcido CD, Larochelle A, Taylor BJ, et al. Molecular characterisation of side population cells with cancer stem cell-like characteristics in small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 2010;102:1636–1644.

Zhou S, Schuetz JD, Bunting KD, et al. The ABC transporter Bcrp1/ABCG2 is expressed in a wide variety of stem cells and is a molecular determinant of the side-population phenotype. Nat Med 2001;7:1028–1034.

Jiang F, Qiu Q, Khanna A, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 is a tumor stem cell-associated marker in lung cancer. Mol Cancer Res 2009;7:330–338.

Bertolini G, Roz L, Perego P, et al. Highly tumorigenic lung cancer CD133+ cells display stem-like features and are spared by cisplatin treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009;106:16281–16286.

Bylund M, Andersson E, Novitch BG, et al. Vertebrate neurogenesis is counteracted by Sox1-3 activity. Nat Neurosci 2003;6:1162–1168.

Li XL, Eishi Y, Bai YQ, et al. Expression of the SRY-related HMG box protein SOX2 in human gastric carcinoma. Int J Oncol 2004;24:257–263.

Masui S, Nakatake Y, Toyooka Y, et al. Pluripotency governed by Sox2 via regulation of Oct3/4 expression in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol 2007;9:625–635.

Güre AO, Stockert E, Scanlan MJ, et al. Serological identification of embryonic neural proteins as highly immunogenic tumor antigens in small cell lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000;97:4198–4203.

Rodriguez-Pinilla SM, Sarrio D, Moreno-Bueno G, et al. Sox2: a possible driver of the basal-like phenotype in sporadic breast cancer. Mod Pathol 2007;20:474–481.

Phi JH, Park SH, Kim SK, et al. Sox2 expression in brain tumors: a reflection of the neuroglial differentiation pathway. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:103–112.

Chen Y, Shi L, Zhang L, et al. The molecular mechanism governing the oncogenic potential of SOX2 in breast cancer. J Biol Chem 2008;283:17969–17978.

Gangemi RM, Griffero F, Marubbi D, et al. SOX2 silencing in glioblastoma tumor-initiating cells causes stop of proliferation and loss of tumorigenicity. Stem Cells 2009;27:40–48.

Bass AJ, Watanabe H, Mermel CH, et al. SOX2 is an amplified lineage-survival oncogene in lung and esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. Nat Genet 2009;41:1238–1242.

Hussenet T, Dali S, Exinger J, et al. SOX2 is an oncogene activated by recurrent 3q26.3 amplifications in human lung squamous cell carcinomas. PLoS One 2010;5:e8960.

Yuan P, Kadara H, Behrens C, et al. Sex determining region Y-Box 2 (SOX2) is a potential cell-lineage gene highly expressed in the pathogenesis of squamous cell carcinomas of the lung. PLoS One 2010;5:e9112.

Lu Y, Futtner C, Rock JR, et al. Evidence that SOX2 overexpression is oncogenic in the lung. PLoS One 2010;5:e11022.

Sholl LM, Barletta JA, Yeap BY, et al. Sox2 protein expression is an independent poor prognostic indicator in stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:1193–1198.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr T Tsukamoto for kindly providing cell lines and Dr T Kitamura for kindly providing the retrovirus system. This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan (to NS), the program for developing the supporting system for upgrading education and research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (to NS) and Takeda Science Foundation (to YH).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

The stem cell transcription factor SOX2 is ectopically overexpressed in lung adenocarcinomas. It is preferentially expressed in cancer-stem cells isolated from lung adenocarcinoma cells, and enhances tumorigenicity of lung cancer cell lines. Therefore, SOX2 may have a role in tumorigenicity of lung adenocarcinoma and is a potential target for treatment.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nakatsugawa, M., Takahashi, A., Hirohashi, Y. et al. SOX2 is overexpressed in stem-like cells of human lung adenocarcinoma and augments the tumorigenicity. Lab Invest 91, 1796–1804 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.2011.140

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.2011.140

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

CAMK2A supported tumor initiating cells of lung adenocarcinoma by upregulating SOX2 through EZH2 phosphorylation

Cell Death & Disease (2020)

-

Functional characterization of SOX2 as an anticancer target

Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (2020)

-

Novel HDAC11 inhibitors suppress lung adenocarcinoma stem cell self-renewal and overcome drug resistance by suppressing Sox2

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

WNT signaling – lung cancer is no exception

Respiratory Research (2017)

-

Enhanced therapeutic effect of an antiangiogenesis peptide on lung cancer in vivo combined with salmonella VNP20009 carrying a Sox2 shRNA construct

Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2016)