Abstract

The classification of primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphoma (PCLBCL) is based on standard morphology, immunohistochemistry, and clinical presentation. There are two major subtypes in the current WHO–EORTC classification: follicle center lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg-type (DLBCL-LT). The goals of this study were to examine a series of DLBCLs to determine (1) whether the immunohistochemical paradigm of germinal center B-cell and non-germinal center B-cell types of systemic DLBCL could be applied to PCLBCL; (2) whether application of the newly described germinal center B-cell marker, human germinal center-associated lymphoma (HGAL) also discriminates between these types as a further support for germinal center B-cell origin for primary cutaneous center lymphoma; and (3) whether any of these biologic markers were of prognostic significance. To this end, 32 cases of diffuse PCLBCL (22 primary cutaneous follicular center lymphomas and 10 DLBCL-LT) were classified based on the WHO–EORTC criteria and studied for expression of CD20, BCL2, BCL6, CD10, MUM-1, and HGAL by immunohistochemistry. Results were correlated with clinical features. HGAL and BCL6 expression and germinal center B-cell phenotype were associated with primary cutaneous follicular center lymphoma. The combination of HGAL and BCL6 positivity had the highest sensitivity (88%) and specificity (100%) for predicting subtype compared to either marker alone. Both HGAL and BCL6 were associated with the germinal center B-cell phenotype. The correlation of HGAL expression with the germinal center B-cell phenotype demonstrates the role of this marker in the classification of cutaneous large B-cell lymphomas. BCL6 expression was the only immunohistochemical marker associated with overall survival. Characterizing PCLBCLs with markers of B-cell maturation stage is a useful framework for studying, classifying, and clinically stratifying these lymphomas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphomas (PCLBCLs) with a diffuse architecture may be classified as primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of leg-type (DLBCL-LT), and DLBCL, other, in the WHO–EORTC classification.1 The first two comprise the majority of the cases. In DLBCL-LT, tumor cells are predominantly centroblasts/immunoblasts, with few admixed reactive elements. It is clinically aggressive and is associated with a 55% 5-year survival.1 Tumor cells in PCFCL may grow in a nodular pattern and consist of a variable proportion of centrocytes/centroblasts. Some cases may also grow in a diffuse manner. This morphology might well lead to a classification as DLBCL in a non-cutaneous site. However, unlike DLBCL-LT, PCFCL behaves indolently and is associated with a 95% 5-year survival. Array-based comparative genomic hybridization analysis revealed differences in chromosomal alterations between PCFCL and DLBCL-LT.2 This finding provided further support for this classification. PCLBC, other, according to the WHO–EORTC classification, refers to rare cases of large B-cell lymphomas arising in the skin, which do not belong to either the group of PCFCL or the group of DLBCL-LT. Cases such as anaplastic or plasmablastic subtypes, intravascular large B-cell lymphomas, or T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphomas would be classified under this category.

In non-cutaneous DLBLC, gene expression profiling has led to the discovery of distinct types of DLBCL3, 4 as germinal center B-cell (GCB)-like DLBCL and activated B-cell (ABC)-like DLBCL. These two subtypes have different prognoses, with GCB type having a significant better overall survival (OS) than those with ABC type. GCB-like DLBCL, characterized by expression of genes normally expressed in germinal center lymphocytes, is associated with prolonged survival. ABC-like DLBCL, characterized by expression of genes expressed in normal mitogen-stimulated lymphocytes, is associated with short survival. Another study using an oligonucleotide array has demonstrated that DLBCL can be divided into two molecularly distinct populations.5 In a later study, it was shown that the genetic alterations have prognostic importance independent of the International Prognostic Index.6 Subsequent studies have also shown that segregation of cases into GCB and non-GCB types by immunohistochemistry in fixed tissues using antibodies to CD10, BCL6, and MUM-1 could closely recapitulate the gene expression profiling classification.7

PCFCL and DLBCL-LT have expression profiles similar to that of GCB and non-GCB DLBCL, respectively.8 This suggests a similarity to systemic DLBCL in conceptualization of the histogenesis of cutaneous large B-cell lymphomas with a diffuse architecture. Although immunohistochemical studies were performed in several earlier studies,8, 9 it is unknown whether an immunohistochemical model similar to that in systemic DLBCL can be applied for tumor classification in the major types of PCLBCLs is presently unknown.

HGAL, human germinal center-associated lymphoma, is a newly characterized germinal center B-cell marker. It was shown to be expressed in germinal center B lymphocytes and in lymphomas of germinal center derivation, such as Burkitt lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma, and diffuse large B-cell lymphomas.10 The expression of HGAL is similar to CD10 and BCL6 in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. However, its expression in primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma has not been studied.

We examined a series of diffuse PCLBCLs for expression of markers that are of importance in classification and prognosis in nodal DLBCLs and PCLBCLs,8, 11, 12 including BCL2, BCL6, MUM-1, HGAL, and CD10. Correlation of these biologic markers with OS was then determined.

Methods

Case Material and Clinical Follow-up

Biopsy or excision specimens from 32 patients of PCLBCL with a completely diffuse architecture were selected from the six participating institutions. Cases with follicular growth pattern either by morphologic or immunophenotypic evidence (presence of an intact follicular dendritic meshwork by CD21 stain) were excluded. Eleven cases were previously reported.12 The study was carried out in accordance with local IRB guidelines. PCLBCL was defined by predominance of large B cells in a diffuse pattern and absence of extracutaneous dissemination after standard staging investigations (clinical examination, bone marrow biopsy, and radiographic studies when available). Cases were classified as PCFCL or DLBCL-LT according to the WHO–EORTC classification of primary cutaneous lymphomas.1 All cases were reviewed by two pathologists (JRC and EDH) and a consensus diagnosis was reached. The OS was recorded by chart review with follow-up ranging from 3 to 245 months (median 36 months).

Immunohistochemical Analysis

Immunohistochemical stains were performed on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues. A panel of antibodies was used, including CD20, BCL2, BCL6, MUM-1, CD10, CD21, and HGAL (Table 1). Cases were scored positive if >5% of the tumor cells were stained, as previously reported.12 Subclassification into GCB type vs non-GCB type was performed by criteria defined by Hans et al,7 using the proposed 30% threshold for the relevant markers, ie, CD10, BCL6, and MUM-1. Cases were assigned to the GCB group if CD10 alone was positive or if both BCL6 and CD10 were positive. If both BCL6 and CD10 were negative, the cases were assigned to the non-GCB subgroup. If BCL6 was positive and CD10 was negative, the expression of MUM-1 determined the group: if MUM-1 was negative, the case was assigned to the GCB group; if MUM-1 was positive, the case was assigned to the non-GCB group. Cases with intact follicular dendritic cell meshwork by CD21 stain were excluded from this study.

Statistics

Fisher's exact and Student's t-tests were used to perform group comparison with respect to categorical and numerical data, respectively. OS was calculated as the time from first diagnosis until death or last follow-up. OS analysis was performed by log rank test using Kaplan–Meier method using R version 1.9.0 (www.R-project.org).

Results

Patient Characteristics

Table 2 includes the clinical and the immunophenotypic data of the patients in our series. Of the 32 patients, there were 18 (56%) women and 14 (44%) men, median age of 62 years. Twenty-two patients (69%) were diagnosed with PCFCL (8 women, 14 men; mean age 55±15, range of 17–78 years) and 10 patients (31%) were diagnosed with DLBCL-LT (all were women with a mean age of 79±15, range of 41–92 years). With the exception of one case, which was located on the scalp, all other DLBCL-LT was located on the leg. The distribution of the diffuse PCFCL was more heterogeneous, with the largest proportion of the patients (9/22) presenting with lesions on the head, and the rest presenting with lesions on the back (6/22), abdomen (1/22), chest (2/22), arm (2/22), buttock (1/22), and hip (1/22). Older age, female gender, and location on the leg were associated with DLBCL-LT (P=0.001, P=0.001, and P<0.0001, respectively, Table 3).

Immunohistochemical results

In all cases, the tumor cells were positive for CD20 and negative for CD3. Selected profiles of DLBCL-LT and PCFCL are shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. Only four cases had rare follicular dendritic cell collections that were either disrupted or overrun by the tumor infiltrate. Table 3 lists the number of cases that were positive for BCL2, BCL6, MUM-1, CD10, and HGAL in the PCFCL or DLBCL-LT patients (using 5% as cutoff for positivity). The GCB vs non-GCB subclassification commonly used in systemic DLBCL is also included (using the algorithm of Hans et al7 with a 30% cutoff). BCL6 expression was present in all (22/22) PCFCL patients, while it was present in 3 of 10 DLBCL-LT patients. BCL2 expression was present in all (10/10) DLBCL-LT patients, while it was present in 9 of 22 PCFCL patients. CD10 expression was present in only 7 of 22 PCFCL and 3 of 10 DLBCL-LT patients. MUM-1 expression was present in 11 of 22 PCFCL and 8 of 10 DLBCL-LT patients. HGAL expression was present in 15 of 17 PCFCL and 3 of 9 DLBCL-LT patients.

BCL6, HGAL, and GCB phenotypes were associated with PCFCL (P=<0.0001, P=0.008, and P=0.019, respectively), while BCL2 expression was associated with DLBCL-LT (P=0.002). HGAL and BCL6 correlated with the GCB phenotype (P=0.01 for both markers). There were no differences in the expression of CD10 and MUM-1 between PCFCL and DLBCL-LT. While both BCL6 and HGAL were useful in classifying a case as PCFCL, the combination of BCL6+/HGAL+ for PCFCL had the greater sensitivity (88%) and specificity (100%) than either marker alone. The sensitivity and specificity for BCL6 were 100 and 70%. For HGAL alone, sensitivity was 88% while specificity was 67%.

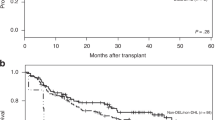

Survival Analysis

Follow-up data were available in 29 patients. In the 19 patients with PCFCL, the median follow-up was 53 months with a range of 3–245 months. Follow-up3, 5, 13, 14 information was available for all 10 patients with DLBCL-LT. The median follow-up was 26 months with a range of 6–85 months. Overall, 2 of 19 patients with PCFCL and 4 of 10 patients with DLBCL-LT died at the end of a 3-year follow-up. Overall, the mortality was low, reflecting the relatively good behavior of the PCLBCL in general. Factors associated with shorter OS were female gender (P=0.030) and BCL6 negativity (P=0.002). DLBCL-LT was of borderline significance (P=0.052) (data not shown). Expression of HGAL, BCL2, MUM-1, CD10, and GCB phenotypes was not associated with outcome.

Discussion

Great insight into the biology of systemic DLBCL was gained from gene expression profiling studies that demonstrated existence of different subtypes of DLBCL based on their similarity to GCBs and ABCs.3, 5, 13, 14 These types not only have biologic relevance but also clinical importance, with ABC-like subtypes of DLBCL having a markedly shorter survival compared to GCB-like subtypes, independent of other known clinical prognostic factors. In recent years, attempts have been made to study cutaneous B-cell lymphomas in a similar manner. Hoefnagal et al8 showed that PCFCL and DLBCL-LT have gene expression profiles similar to the GCBs and ABCs, respectively. In that study, immunohistochemical staining for MUM-1 protein expression showed that MUM-1 was highly expressed in the DLBCL-LT, but not in PCFCL. Interestingly, the same group preceded this with an immunohistochemical study suggesting that all large B-cell lymphoma including the leg-type large-cell lymphomas were of GC origin.9 However, MUM-1 was not evaluated in that study. We studied a series of PCLBCLs specifically with a diffuse architecture. Our aims were to determine (1) whether the morphologic type (PCFCL and DLBCL-LT) correlated with the expression of typical markers useful in subclassifying or stratifying nodal DLBCL such as CD10, BCL6, BCL2, and MUM-1; (2) whether it correlated with a new GCB marker (HGAL); and (3) whether any of these markers might be associated with OS.

In this study, we have shown that morphologic criteria are reliable in separating these two entities using the WHO–EORTC classification. Using the criteria of Hans et al,7 we could subclassify our cases into GCB and non-GCB types, which in turn, correlated with the morphologic diagnosis of PCFCL and DLBCL-LT. These results are concordant with the gene profiling data, suggesting that DLBCL-LT exhibits an ABC-like gene expression profile and PCFCL exhibits a GCB-like gene expression profile. While there was a strong association between the germinal center and post-germinal center immunophenotypes and the two types of PCLBCL, this was not a perfect association, that is, both groups contained a minority of outlier cases in this respect.

Furthermore, we found that the specific GCB marker HGAL was indeed preferentially expressed in diffuse PCFCL and correlated with GCB phenotype. Indeed, our data show that, while both HGAL and BCL6 are associated with PCFCL, the combined expression of both markers has the best sensitivity and specificity for distinguishing PCFCL and DLBCL-LT. Thus, the immunohistochemical ‘cell of origin’ concepts in systemic DLBCL appear to hold in primary cutaneous DLBCLs.

Comparison of the immunophenotype in our cases to the previously published data (Table 4)8, 9, 15, 16 is challenging, largely due to lack of a uniform criteria for positive or negative. In addition, subclassification varies according to classification system used. In the study of Goodlad et al,15 the cases was classified into DLBCL-LT and DLBCL-upper body, irrespective of the cytologic features, ie, ‘cleaved’ or ‘round’ cells. In the study of Kodama et al,11 a specific marker was scored positive only when the majority of the tumor cells expressed the proteins. In the two studies published by Hoefnagel et al,8, 9 different scoring systems were used. In one study, 10% staining was used as a cutoff for MUM-1,8 while 25% staining was used as a cutoff in the other study for BCL2 and BCL6.9

We chose to use 5% in our scoring system, consistent with previous criteria used by Sundram et al.12 This scoring system has also been used by other investigators.12, 17 Nevertheless, BCL2 expression was similar across studies in that it was positive in all the DLBCL-LT. The higher CD10 expression in our study was due to the cutoff used. When the cutoff was increased (30% of tumor cell staining), CD10 was expressed in 6/22 (27%) and 1/10 (10%) in PCFCL and DLBCL-LT, respectively. In our series, MUM-1 expression was not significantly different between the two subtypes. These results were quite different in comparison to the studies by Hoefnagel et al9 and Kodama et al11 The reasons for the difference were unclear, but may be due to technical factors. Similar to Hoefnagel et al9 and Kodama et al, 11 BCL6 was seen in all PCFCL. In contrast, we found BCL6 expression in fewer cases of DLBCL-LT than reported. The reason for this discrepancy is unknown. In our series, BCL6, a GCB marker is more highly expressed in PCFCL compared to DLBCL-LT, which is consistent with the germinal center origin of PCFCL. Most recently, a large series of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas has been published. The results are similar with the exception of CD10 and MUM-1 (found at substantially higher frequency in PCFCL in our series). This may be explained by differences in cutoff, with Senff et al16 using a much higher threshold (50% for BCL6, CD10, and BCL2; 30% for MUM-1) for these markers.

Recognizing limitations due to a relatively small number of events, we also attempted to correlate immunophenotypic findings with OS. DLBCL-LT subtype was of borderline significance as an adverse predictor for OS. Of all the markers, only expression of BCL6 was associated with OS. This was in concordance with the previous published results.12 We have included some of the cases from this particular study in our series. However, we have performed separate analysis by excluding the cases from Sundram et al,12 the results trended the same way. Most of the cases that lack BCL6 in our series tended to belong to the DLBCL-LT with BCL2 expression, features known to be associated with shorter survival.9, 15 Since lack of BCL6 is also consistent with a non-GCB type of lymphoma, the shorter survival in BCL6-negative cases might be expected. Although HGAL was associated with PCFCL and GCB phenotypes, it was not associated with OS, perhaps due to relatively few death events in our cohort.

In this study, we suggest an evolution of the concept for cutaneous DLBCL from clinically based descriptive system that includes anatomic site to a perhaps more biologically oriented system. In accordance with prior gene expression profiling and immunophenotypic studies (both in cutaneous and systemic large B-cell lymphomas),3, 4, 8, 13 we show that GCB and non-GCB immunophenotypic models of systemic DLBCL are applicable to cutaneous lymphomas, and correlate with morphological subtypes. Namely, GCB phenotype correlates with PCFCL, while DLBCL-LT is associated with non-GCB type. In addition to standard markers, the HGAL expression pattern supports this model. In fact, the combination of BCL6 and HGAL expression showed high specificity and sensitivity for identifying PCFCL. This is in concordance with conceptualization of lymphomas (including cutaneous lymphomas) as abnormal counterparts of normal B-cell development. Clearly, larger studies of this uncommon form of lymphoma are needed. These studies serve to advance our understanding of the biology of cutaneous lymphomas and to unify, rather than separate, their classification.

References

Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO–EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood 2005;105:3768–3785.

Dijkman R, Tensen CP, Jordanova ES, et al. Array-based comparative genomic hybridization analysis reveals recurrent chromosomal alterations and prognostic parameters in primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:296–305.

Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Davis RE, et al. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature 2000;403:503–511.

Rosenwald A, Wright G, Chan WC, et al. The use of molecular profiling to predict survival after chemotherapy for diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1937–1947.

Shipp MA, Ross KN, Tamayo P, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma outcome prediction by gene-expression profiling and supervised machine learning. Nat Med 2002;8:68–74.

Bea S, Zettl A, Wright G, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma subgroups have distinct genetic profiles that influence tumor biology and improve gene-expression-based survival prediction. Blood 2005;106:3183–3190.

Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, et al. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood 2004;103:275–282.

Hoefnagel JJ, Dijkman R, Basso K, et al. Distinct types of primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Blood 2005;105:3671–3678.

Hoefnagel JJ, Vermeer MH, Jansen PM, et al. Bcl-2, Bcl-6 and CD10 expression in cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: further support for a follicle centre cell origin and differential diagnostic significance. Br J Dermatol 2003;149:1183–1191.

Natkunam Y, Lossos IS, Taidi B, et al. Expression of the human germinal center-associated lymphoma (HGAL) protein, a new marker of germinal center B-cell derivation. Blood 2005;105:3979–3986.

Kodama K, Massone C, Chott A, et al. Primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphomas: clinicopathologic features, classification, and prognostic factors in a large series of patients. Blood 2005;106:2491–2497.

Sundram U, Kim Y, Mraz-Gernhard S, et al. Expression of the bcl-6 and MUM1/IRF4 proteins correlate with overall and disease-specific survival in patients with primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphoma: a tissue microarray study. J Cutan Pathol 2005;32:227–234.

Bea S, Zettl A, Wright G, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma subgroups have distinct genetic profiles that influence tumor biology and improve gene-expression-based survival prediction. Blood 2005;106:3183–3190.

Tagawa H, Suguro M, Tsuzuki S, et al. Comparison of genome profiles for identification of distinct subgroups of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2005;106:1770–1777.

Goodlad JR, Krajewski AS, Batstone PJ, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: prognostic significance of clinicopathological subtypes. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27:1538–1545.

Senff NJ, Hoefnagel JJ, Jansen PM, et al. Reclassification of 300 primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas according to the new WHO–EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas: comparison with previous classifications and identification of prognostic markers. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:1581–1587.

Gratzinger D, Zhao S, Marinelli RJ, et al. Microvessel density and expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma subtypes. Am J Pathol 2007;170:1362–1369.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, X., Sundram, U., Natkunam, Y. et al. Expression of HGAL in primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphomas: evidence for germinal center derivation of primary cutaneous follicular lymphoma. Mod Pathol 21, 653–659 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2008.30

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2008.30

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Double-hit or dual expression of MYC and BCL2 in primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphomas

Modern Pathology (2018)

-

Managing Patients with Cutaneous B-Cell and T-Cell Lymphomas Other Than Mycosis Fungoides

Current Hematologic Malignancy Reports (2016)

-

Comparison of germinal center markers CD10, BCL6 and human germinal center-associated lymphoma (HGAL) in follicular lymphomas

Diagnostic Pathology (2011)