Abstract

The distribution and pathological significance of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 expression are still unclear. In this study, we evaluated sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1's suitability as a diagnostic marker for malignant lymphoma by immunostaining formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections using a well-defined commercial anti-sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 antibody. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 was strongly expressed on the surface of small lymphocytes forming primary lymphoid follicles and in the mantle zone of secondary lymphoid follicles. Microarray-based immunohistochemistry with tissue samples from 85 lymphoid malignancy cases demonstrated that sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 was expressed on the surface of mantle cell lymphoma cells. Strong expression was observed in all classical mantle cell lymphoma cases involving the lymph node (19 out of 19), gastrointestinal tract (10 out of 10), bone marrow (9 out of 9), and orbita (1 out of 1). Good results were obtained even in sections where cyclin D1 signals were lost because of over-fixation and/or decalcification. One aggressive variant of mantle cell lymphoma displayed a weaker membranous staining than classical mantle cell lymphoma in the lymph node and bone marrow. In a cyclin D1-negative mantle cell lymphoma of the orbita, no conclusive result was obtained. No cases of follicular lymphoma, marginal zone lymphoma, B lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma, or Burkitt's lymphoma showed any significant expression, whereas 2 out of 6 chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphomas in bone marrow, 1 out of 3 lymphoplasmacytic lymphomas in the lymph node, and 2 out of 37 diffuse large B-cell lymphomas exhibited staining. A quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction-based analysis of mantle cell lymphoma lines revealed the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 mRNA expression level to be well correlated with the results of immunocytochemistry, flow cytometry, and western blotting. Thus, sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 immunohistochemistry may be useful in the histological diagnosis of mantle cell lymphoma with formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded sections. The antigen may be particularly valuable in cases where cyclin D1 immunostaining is not successful.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Mantle cell lymphoma is a well-defined clinicopathological entity characterized by a proliferation of CD5-positive B-cell lymphocytes, which may be derived from primary lymphoid follicles or the mantle zone of secondary follicles.1, 2 This lymphoma shows translocation t(11;14)(q13;q32) and overexpression of cyclin D1, and exhibits a poor response to conventional chemotherapy resulting in a relatively short survival period. Distinguishing mantle cell lymphoma from other small B-cell lymphomas such as marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, and chronic lymphocytic lymphoma/small lymphocytic lymphoma, is important because of differences in patient management.3 Cyclin D1 overexpression is a hallmark of mantle cell lymphoma, but in a small proportion of cases, the spectrum of morphological and phenotypic features is broader than initially described. Moreover, cyclin D1-related immunohistochemistry is easily affected by technical factors including fixation time4 and decalcification, and recently, mantle cell lymphoma without cyclin D1 overexpression has been reported.5 Therefore, specific immunohistochemical markers that can serve as a diagnostic tool to distinguish mantle cell lymphoma would be invaluable.

Sphingosine-1-phosphate, a potent lipid mediator produced from the metabolism of sphingolipid by the actions of sphingosine kinase,6, 7 transduces intracellular signals through activation of the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors (S1PR1, S1PR2, S1PR3, S1PR4, and S1PR5), seven-truncated plasma membrane receptors ubiquitously expressed in different tissues.8, 9 The sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor influences different biological processes, such as cell proliferation, survival, migration, and morphogenesis, depending on the relative expression of these sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors coupled to different intracellular second messenger systems, including phospholipase C, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase Akt, as well as Rho- and Ras-dependent pathways.6, 7, 8, 9 The S1PR1 gene is located on chromosome 1p21 and was initially isolated as endothelial differentiation gene-1 from human endothelial cells.10 S1PR1 is widely expressed in adult tissues including endothelial cells, the brain, and the cells of the immune system.11 Both T- and B-lymphocytes have been shown to use sphingosine-1-phosphate/S1PR1 signaling for trafficking.9, 12, 13, 14 However, most findings have been obtained from experiments using mice. The precise distribution and exact roles of S1PR1 in human disease are still unclear.

We have recently investigated S1PR1 expression in human tissues using an antibody of which the specificity was defined by immunostaining of the vasculature in S1PR1−/− and S1PR1+/− mouse embryos.15 S1PR1 was expressed not only in vascular and lymphatic endothelial cells in all tissues examined, but also in angiosarcoma.16

In this study, we investigated the distribution of S1PR1 in lymphoid tissues using immunohistochemistry. We found that S1PR1 was strongly expressed on small lymphocytes forming primary lymphoid follicles and the mantle zone in secondary lymphoid follicles. We then tested the potential of S1PR1 as a diagnostic marker for mantle cell lymphoma by comparing its expression among B-cell lymphomas.

Materials and methods

The study design was approved by the ethics review board of Kawasaki Medical School.

Antibody

A rabbit polyclonal antibody against amino acids 322–381 of S1PR1 of human origin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology EDG-1 (H60): sc-25489, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) was used. This antibody can react with human S1PR115, 16 and mouse S1PR117, 18 and has been thoroughly checked for specificity by comparing immunostaining results of the vasculature in paraffin sections of S1PR1−/− and S1PR1+/− mouse embryos and an angiosarcoma cell line expressing considerable quantities of S1PR1 mRNA.15

Tissue Specimens

Case materials were obtained from the Kawasaki Medical School Hospital. Normal and neoplastic lymphoid tissue samples were retrieved from the files of the Department of Pathology, Kawasaki Medical School Hospital. Surgical specimens included samples of benign reactive lymph nodes, tonsils, bone marrow, and malignant lymphoma of the lymph nodes and extranodal sites. The diagnosis of the lymphoma cases was confirmed by a combination of histology, flow cytometric immunophenotyping, immunohistochemistry, fluorescence in situ hybridization, Southern blotting, and polymerase chain reaction.

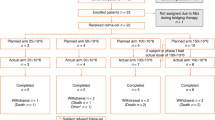

Within the group of B-cell lymphomas, lymph node lymphomas included 25 follicular lymphomas, 4 chronic lymphocytic lymphomas/small lymphocytic lymphomas, 1 CD5-positive marginal zone lymphoma, 20 mantle cell lymphomas (19 classic and 1 aggressive variant), 25 diffuse large B-cell lymphomas including 4 CD5-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, 3 lymphoplasmacytic lymphomas, 3 B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphomas, and 1 plasma cell myeloma. Gastrointestinal tract lymphomas included 10 mantle cell lymphomas, 11 follicular lymphomas (9 duodenal and 2 ileal follicular lymphomas), 1 chronic lymphocytic lymphoma/small lymphocytic lymphoma, 9 extranodal marginal zone lymphomas of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphomas), 5 diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, and 1 Burkitt's lymphoma. Bone marrow lymphomas included 10 mantle cell lymphomas (9 classic and 1 aggressive variant), 7 follicular lymphomas, 6 chronic lymphocytic lymphomas/small lymphocytic lymphomas, 3 lymphoplasmacytic lymphomas, 6 diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, and 1 hairy cell leukemia. Orbita cases included 1 classical mantle cell lymphoma and 1 cyclin D1-negative mantle cell lymphoma, where molecular profiles including somatic mutations of the immunoglobulin variable region heavy chain genes19 had been examined extensively by one of the authors (Abe M). One case of brain diffuse large B-cell lymphoma was also included.

In addition, 3 T-lymphoblastic leukemias/lymphomas, 5 angio-immunoblastic T-cell lymphomas, 10 adult T-cell leukemias/lymphomas, 2 peripheral T-cell lymphomas-not otherwise specified, 2 extranodal NK/T-cell lymphomas nasal type, 6 Hodgkin's lymphomas, 1 blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell leukemia/lymphoma, and 1 systemic mastocytosis were examined.

A tissue microarray composed of 42 diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, 2 Burkitt's lymphomas, 3 small lymphocytic lymphomas, 6 follicular lymphomas, 2 mantle cell lymphomas, 7 MALT lymphomas, 8 Hodgkin's lymphomas, 3 anaplastic large cell lymphomas, 4 peripheral T-cell lymphomas-not otherwise specified, 1 extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma nasal type, 2 T-lymphoblastic leukemias/lymphomas, 3 angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphomas, and 2 plasma cell myelomas.

Cell Culture

Two mantle cell lymphoma lines, Rec-1 established from a lymph node (blastoid variant)20 and Granta-519 established from peripheral blood (leukemic phase),21 were purchased from DSMZ (Braunschweig, Germany). A third, JeKo-1, established from peripheral blood (leukemic phase)22 was obtained from the Fujisaki Cell Bank Center, Hayashibara Biochemical Laboratories (Okayama, Japan). These cell lines were maintained with RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, New York, NY, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum. The angiosarcoma cell line ISO-HAS,23 was cultured in 10% fetal bovine serum in DMEM (Gibco). Immunocytochemical labeling and mRNA expression of S1PR1 had been demonstrated on the ISO-HAS.15

Immunocytochemistry

The mantle cell lymphoma cell lines were treated with RPMI-1640 medium to prepare the cell suspensions to be used in the experiments. The cells were re-suspended in phosphate-buffered saline containing 5% fetal bovine serum and cytospinned to glass slides. ISO-HAS cells, a positive control, were treated in the same manner and also cytospinned to glass slides. They were dried well and fixed in 100% ethanol for 1 min. The cells were stained with a fully automatic immunohistochemical system, Ventana XT system Discovery (Ventana Medical System, Tucson, AZ, USA), using a polyclonal rabbit anti-S1PR1 antibody (1:15 dilution) as described previously.15

Immunohistochemistry

Tissues were fixed in 8% buffered formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4 μm, and stained with the Ventana XT system Discovery using a polyclonal rabbit anti-S1PR1 antibody (1:20 dilution) as described.15 The immunostaining was carried out with an avidin–biotin detection system. The period of incubation with the primary antibody was 15 min. A diaminobenzidine hydrochloride solution with hydrogen peroxide was the chromogen.

Double labeling was carried out to identify the specific cell-type expressing S1PR1. Tissue sections were incubated with the primary antibody mixture for 45 min at room temperature. Sections were incubated with a peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Histofine, Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan), and signals were detected using the diaminobenzidine hydrochloride solution with hydrogen peroxide. Then, sections were incubated with an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary anti-mouse IgG Ab (Histofine) and the signals were detected using a New Fuchsin substrate kit (Histofine).

Routine staining of CD3, CD4, CD8, CD20, CD21, CD23, CD30, CD45RO, CD56, CD79a, bcl-2, and cyclinD1 was conducted to diagnose malignant lymphomas.

Flow Cytometry

The flow cytometric analysis of the mantle cell lymphoma cell lines was conducted using a DAKO IntraStain kit (Dako, Kyoto, Japan) which makes it possible for the anti-S1PR1 antibody to react with the intracytoplasmic portion of the S1PR1 protein as described previously.15 Briefly, Rec-1, and Granta-519 cells (5 × 105) were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and fixed in IntraStain reagent A (Dako). After being washed in phosphate-buffered saline, the cells were treated with IntraStain reagent B and incubated with 1:10 diluted anti-S1PR1 antibody for 15 min. After washes with phosphate-buffered saline, the cells were incubated with IntraStain reagent B and a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (EY Laboratories Inc., San Mateo, CA, USA) for 15 min. After more washes with phosphate-buffered saline, the cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde. For the negative control, cells were processed as described above using an unrelated rabbit antibody. These samples were measured using a FACS Calibur (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA), and the data obtained were analyzed using CellQuest (Becton Dickinson).

Western Blotting

Rec-1, Granta-519, and JeKo-1 cells were cultured, collected, and rinsed three times with phosphate-buffered saline at room temperature. Immediately after the addition of boiled lysis buffer (1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1.0 mM sodium ortho-vanadate, and 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4)), the cells were boiled for 5 min, passed through a 26.5-G needle five times, and centrifuged to prepare cell extracts. Proteins of each cell extract were quantified using a Qubit Fluorometer (Invitrogen, Tokyo, Japan). Next, 10–30 μg each of the extracts and a colored molecular marker (ATTO, Tokyo, Japan) were separated by 5–12% gradient sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. Each membrane was then cut, and treated with a blocking reagent (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) at room temperature for 1 h. A rabbit anti-human S1PR1 antibody (1:100 dilution), or a mouse anti-β actin monoclonal antibody (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) was reacted with the membrane at room temperature for 2 h. The membrane was then washed with Tris-HCl buffer saline for 30 min and incubated at room temperature for 60 min with a mixture of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody and anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Roche Diagnostics). The membrane was washed with Tris-HCl buffer saline for 30 min, treated with ECL plus a western blotting detection system (Roche Diagnostics), and visualized using a cooled charge coupled device camera, ChemiStage CC-16 (KURABO, Osaka, Japan).

Real-Time Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total mRNA was extracted from ISO-HAS, Rec-1, Granta-519, and JeKo-1 cells using an RNeasy Plus Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). cDNA was synthesized from each extract containing one microgram of mRNA using a QuantiTect ReverseTranscription kit (Qiagen). Real-time PCR primers were purchased from Qiagen (QuantiTect Primer Assay) for human S1PR1 (QT00208733), S1PR2 (QT00230846), S1PR3 (QT00244251), S1PR4 (QT01192744), S1PR5 (QT00234178), cyclinD1 (CCND1,QT00495285), human GAPDH (QT01192646), and human β-actin (QT00095431). Gene expression levels were analyzed on an Applied Biosystems 7500 (Tokyo, Japan) with a QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR kit (Qiagen). S1PR1 expression was normalized by comparison with the expression of the housekeeping gene β-actin. The conditions for amplification were 15 min at 95°C to activate the HotStarTaq DNA polymerase, then 40 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, annealing at 55°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 34 s. As the polymerase chain reaction efficiency of the reaction was comparable between the target and endogenous reference gene β-actin, normalized S1PR1, S1PR2, S1PR3, S1PR4, S1PR5, and cyclin D1 expressions were calculated using ABI software and 2−ΔΔCt analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Differences in mRNA expression among the mantle cell lymphoma cell lines were calculated using JMP Statistical Discovery Software, version 7, from the SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA. Statistical significance was defined as a P-value <0.05.

Results

Expression of S1PR1 in Lymphoid Organs

First, we investigated the expression of S1PR1 in adult human hematolymphoid tissues.

In the lymph node, S1PR1 was expressed on the surface of small lymphocytes forming primary follicles and the mantle zone of secondary follicles (Figure 1a). Germinal center cells tested negative for this antigen. Double labeling immunohistochemistry revealed that S1PR1-positive mantle zone lymphocytes tested positive for CD20, but not for CD45RO (Figure 1b and c). Endothelial cells of blood vessels including arteries, veins, and high endothelial venules, and endothelial cells of afferent and efferent lymphatics and the marginal and medullary sinus were strongly stained for S1PR1. A similar staining pattern was observed in the tonsils and Peyer's patches of the small intestine. In bone marrow, megakaryocytes were fairly strongly stained, whereas the staining of sinus endothelial cells was very faint.

Immunostaining for S1PR1 in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections of a reactive lymph node. (a) S1PR1 is expressed on vascular and lymphatic endothelial cells and mantle zone lymphocytes of lymph follicles, but not germinal center lymphocytes. (b and c) Double labeling with an anti-S1PR1 polyclonal antibody (brown) and anti-CD20 (b, red) or anti-CD45RO (c, red) monoclonal antibodies. CD20-positive and CD45RO negative lymphocytes express S1PR1 strongly.

Expression of S1PR1 in a Tissue Microarray of Lymphoid Malignancies

Among 85 cases of lymphoid malignancy, 2 cases of mantle cell lymphoma (CD20+, CD5+, CD10−, and cyclin D1+) showed clear membranous staining with the anti-S1PR1 antibody. Membranous staining was also seen in non-neoplastic small B-lymphocytes and blood vessels in these cases. Among tissue microarrays, one plasmacytoma showed focal cytoplasmic granular staining of tumor cells.

Expression of S1PR1 in Nodal B-Cell Lymphomas

As shown in Table 1, among nodal lymphoma cases, strong membranous expression was seen in 19 out of 19 cases of classical mantle cell lymphoma regardless of subtype (Figure 2a–c; cases 1–19 in Table 2). One aggressive variant of mantle cell lymphoma displayed a weaker membranous staining than classical mantle cell lymphoma (Figure 2d; case 20 in Table 2). This was obvious when compared with endothelial cell staining in the same section. In all, 25 follicular lymphomas, 4 chronic lymphocytic leukemias/small lymphocytic lymphomas, and 1 CD5-positive marginal zone lymphoma did not show any significant expression. One of 3 lymphoplasmacytic lymphomas (case 22 in Table 2), and 2 of 25 diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (cases 23, 24 in Table 2) exhibited membranous staining for S1PR1. The S1PR1-positive lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma was CD20+, CD5−, CD10−, CD23−, s-IgD+, s-IgM+, and cyclinD1− and accompanied by monoclonal IgM gammapathy, but exhibited an unusual nodular growth pattern with strong S1PR1 expression.

Representative photographs of immunostaining for S1PR1 in s of the lymph nodes. (a) Mantle cell lymphoma showing a mantle zone pattern with the remnant germinal center. (b) Mantle cell lymphoma with a nodular pattern mimicking FL. (c) Mantle cell lymphoma with a diffuse pattern. S1PR1 immunostaining displays membranous staining of neoplastic cells. (d) Blastoid mantle cell lymphoma with decreased expression of S1PR1. Strong signals are clearly recognized in blood vessels. (e and f) S1PR1 expression in the orbita of a case diagnosed as cyclin D1-negative mantle cell lymphoma. About 20% of neoplastic cells were positive for S1PR1.

Expression of S1PR1 in Extranodal Small B-Cell Lymphomas

To help distinguish small B-cell lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract, we studied the expression of S1PR1 in 10 cases of mantle cell lymphoma, 11 cases of follicular lymphoma, 9 cases of MALT lymphoma, 1 case of chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, and 5 cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Only the mantle cell lymphomas were stained with the anti-S1PR1 antibody. As compared with cyclin D1 staining, S1PR1 staining consistently provided clearer and stronger signals (Table 1, Figure 3a–d). We also examined an autopsy case of intestinal mantle cell lymphoma in which the specific translocation t(11;14) actually existed, but all immunoreactivity with the rabbit anti-cyclin D1 monoclonal antibody was lost after long-standing fixation. This tumor exhibited clear staining for S1PR1.

Next, we examined the expression of S1PR1 in mantle cell lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic lymphoma/small lymphocytic lymphoma, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, and follicular lymphoma cases involving bone marrow. All the mantle cell lymphomas tested positive for S1PR1. However, unlike in the lymph nodes, the intensity of the staining varied among individual lymphoma cells; some lymphoma cells were not clearly labeled (Figure 4a). We found a case of mantle cell lymphoma, which lost CD20 expression because of treatment with rituximab, but exhibited S1PR1 expression. In total, 2 out of 6 chronic lymphocytic lymphomas/small lymphocytic lymphomas showed staining (case 25 in Table 2, Figure 4b and case 26 in Table 2). However, one was an atypical chronic lymphocytic lymphoma with a CD23− phenotype. None of the bone marrow follicular lymphomas or diffuse large B-cell lymphomas showed any significant expression (Table 1).

Representative photographs of the bone marrow involvement in a patient with mantle cell lymphoma (a) and chronic lymphocytic lymphoma/small lymphocytic lymphoma (b). (a) Neoplastic cells show viable staining. (b) The staining of neoplastic cells is considerably weaker than that of capillary endothelial cells as an intrinsic control.

Next, we explored the diagnostic potential of S1PR1 immunohistochemistry for cyclin D1-negative mantle cell lymphoma. Only one case of cyclin D1-negative mantle cell lymphoma was available, which occurred in the orbita and exhibited a CD20+, CD5+, CD10−, CD23−, CD43+, BCL-2+, and BCL-6− phenotype. This tumor was morphologically diagnosed as mantle cell lymphoma and showed 5% somatic mutation rate of the immunoglobulin variable region heavy chain, but it lacked cyclin D1 mRNA and protein expression and t(11;14) (case 21 in Table 2). In this case, about 20% of neoplastic cells were stained for S1PR1 (Figure 2e and f).

S1PR1 Expression in T-Cell, T/NK-Cell and Hodgkin's Lymphomas

Among 21 cases of T-cell lymphoma, 3 cases of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma showed clear membranous staining. Tumor cells of extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma nasal type, blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell leukemia/lymphoma, and systemic mastocytosis tested negative for S1PR1. In cases of Hodgkin's lymphoma, staining was predominantly localized to the non-neoplastic component, particularly tumor-infiltrating small lymphocytes and vascular endothelial cells, whereas weak expression was seen on some Reed–Sternberg cells.

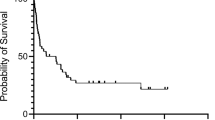

Expression of S1PR1 in Mantle Cell Lymphoma Cell Lines

The protein expression of S1PR1 of blastoid mantle cell lymphoma (Rec-1) and leukemic mantle cell lymphoma (JeKo-1 and Granta-519) cell lines was examined using immunocytochemistry, flow cytometry, and western blotting. The angiosarcoma cell line ISO-HAS was used as a positive control. On western blotting, reaction products were clearly seen in ISO-HAS cells and weakly detected in Rec-1 cells with a molecular weight of about 40–45 kDa, but were not seen in JeKo-1 or Granta-519 cells (Figure 5a and b). Similarly, flow cytometric analysis and immunocytochemical staining revealed that S1PR1 protein was expressed in Rec-1 cells (Figure 6a and c) but not in JeKo-1 or Granta-519 cells (Figure 6b and d). To confirm the correlation with the findings on protein expression, we next examined the mRNA expression of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors in these mantle cell lymphoma cell lines by quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. When the relative quantity of S1PR1 mRNA of ISO-HAS cells was 1.0, that of Rec-1 cells was significantly higher than the level in JeKo-1 or Granta-519 cells (0.55±0.25 vs 0.10±0.04 and 0.06±0.04, mean±s.d., n=4) (P<0.001). The relative quantities of cyclin D1 mRNA in Rec-1, JeKo-1, and Granta-519 cells were 17.5, 16.4, and 16 (mean, n=2) times respectively, that of ISO-HAS. The relative quantities of S1PR2, S1PR3, S1PR4, and S1PR5 mRNA were quite low compared with the amount of S1PR1 mRNA in Rec-1 cells.

Comparative study of mantle cell lymphoma cell lines based on western blotting of S1PR1. (a) The positive control angiosarcoma cell line ISO-HAS gives a strong signal. A weaker signal is seen in Rec-1, whereas no signal is observed in Granta-519 or JeKo-1. (b) Positive signals are seen at 40–45kDa. The level of S1PR1 protein in Rec-1 cells is very low compared with that in ISO-HAS cells and 30 μg of protein per lane is necessary to obtain a signal.

Comparative study of mantle cell lymphoma cell lines based on flow cytometric and immunocytochemical analyses of S1PR1. (a and b) Flow cytometric analysis. Clear staining is seen in Rec-1 (a), but not Granta-519 (b). (c and d) Immunocytochemistry. A fine membranous staining is seen in Rec-1 (c), but not Granta-519 (d).

Discussion

This study is the first to systematically document the expression of S1PR1 in human lymphoid tissues and B cell lymphomas. Although S1PR1 has been shown to be expressed on human T- and B-lymphocytes9, 24 and vascular and lymphatic endothelial cells, the in situ localization of S1PR1 in human tissues has not been examined. In this study, we found that mantle cells and their malignant counterpart, mantle cell lymphoma cells, strongly expressed S1PR1.

In the lymph nodes, strong S1PR1 expression was mainly restricted to mantle cells whereas faint expression was seen in paracortical T-lymphocytes. No staining was seen in follicle center B cells of lymphoid tissues or in lymphocytes of bone marrow. These results suggest that B-lymphocytes express S1PR1 depending on their state of differentiation and location and the expression levels are modulated following stimulation by the B-cell receptor.

The classification of small B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders is based on a combination of clinical, morphological, immunophenotypic, and cytogenetic parameters.1 Immunohistochemical analysis is particularly helpful in establishing the diagnosis because there is significant clinical and morphologic overlap among mantle cell lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic lymphoma/small lymphocytic lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, and marginal zone lymphoma.1, 25 Mantle cell lymphoma cases may occasionally display an unusual phenotype such as a lack of CD5 and co-expression of CD10 or CD23, and the distinction from other small B-lymphocytic lymphomas, especially chronic lymphocytic lymphomas/small lymphocytic lymphomas, does not appear straightforward.25, 26 This study demonstrated the utility of S1PR1 immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of mantle cell lymphoma, but revealed two cases of S1PR1-positive chronic lymphocytic lymphoma/small lymphocytic lymphoma, one of which was negative for CD23. Recent studies suggested that mantle cells are derived from naïve pre-germinal center B-cells,1, 27 but chronic lymphocytic lymphoma/small lymphocytic lymphoma can be divided into naïve and memory B-cell types based on the absence or presence of somatic mutations in the immunoglobulin variable region heavy chain.1, 19, 28 Thus, it would be useful to confirm whether the origin of S1PR1-positive chronic lymphocytic lymphoma is naïve B-cells. Further study with more cases and an analysis of the immunoglobulin variable region heavy chain's status is needed to clarify a correlation between S1PR1 positivity and the chronic lymphocytic lymphoma/small lymphocytic lymphoma type.

One possible application of the anti-S1PR1 antibody is in the diagnosis of cyclin D1-negative mantle cell lymphoma. There may be different forms of cyclin D1-negative mantle cell lymphoma, one in which the specific translocation actually exists, but no immunostaining of cyclin D1 is obtained,29 and a second type lacking t(11;14)(q13;q32), but showing morphological features of mantle cell lymphoma.5 This study demonstrated the usefulness of S1PR1 immunohistochemistry in the former type of cyclin D1-negative mantle cell lymphoma because the epitope of S1PR1 is more stable in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues than that of cyclin D1. Clear staining was obtained even in gastrointestinal and bone marrow sections where cyclin D1 signals were lost because of over-fixation and/or decalcification. Therefore, the combination of immunohistochemistry with a panel of antibodies for CD20, CD5, CD23, cyclin D1, and S1PR1 should provide a more accurate diagnosis of mantle cell lymphoma. On the other hand, it is unclear whether S1PR1 immunostaining is applicable to the diagnosis of true cyclin D1-negative mantle cell lymphoma.

It has been shown that the nuclear expression of Sox11, a neuronal transcription factor, is useful as a diagnostic marker for mantle cell lymphoma and the distribution of this marker can be used to identify subsets of mantle cell lymphoma.30, 31 Sox11 is also expressed on cyclin D1-negative mantle cell lymphoma cells.30 In contrast to Sox11, S1PR1 immunohistochemistry did not demonstrate subgroups of mantle cell lymphoma, except for one aggressive variant with weaker immunostaining.

S1PR1 mRNA levels of JeKo-1 and Granta-519 cells, both of which are derived from leukemic mantle cell lymphoma, were very low compared with the level in Rec-1 cells. No reactivity was detected in JeKo-1 and Granta-519 cells by immunocytochemical staining, flow cytometry, or western blotting with the anti-S1PR1 antibody. These results suggest a further analysis of S1PR1 expression in a larger number of mantle cell lymphoma cases, including aggressive and leukemic variants, to be warranted.

The function of S1PR1 has been studied extensively in mice,13, 14, 32 but is still unclear in human tissues. S1PR1 may not be merely a diagnostic marker, but may also have some role in the behavior of mantle cell lymphoma because it has been shown to be involved in the regulation of motility in a variety of cell types33 and is crucial for lymphocyte egression or localization in lymphoid organs.9, 13, 14 Mantle cell lymphoma cell trafficking to bone marrow and the gastrointestinal tract may be regulated by S1PR1 in cooperation with chemokine receptors and adhesion molecules.34 Another possible role for S1PR1 in mantle cell lymphoma is in the regulation of the proliferation and apoptosis of mantle cell lymphoma cells,6, 7 which may have treatment-related implications. In this regard, Bayerl et al.35 recently reported that sphingosine kinase 1, the enzyme responsible for sphingosine-1-phosphate production, is overexpressed in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and is thus a possible target for new pharmacological interventions. Therefore, this study provides a rationale to further investigate the therapeutic potential of drugs targeting the S1PR1 pathway, such as FTY 720,36 in mantle cell lymphoma.

In conclusion, S1PR1 was strongly expressed on the membranes of mantle cell lymphoma cells as well as small lymphocytes forming the mantle zone in lymph nodes. None of the follicular lymphomas or marginal zone lymphomas showed any significant expression, suggesting S1PR1 could be a new diagnostic adjunct to cyclin D1 for distinguishing mantle cell lymphoma from morphological mimics.

References

Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Seto M, et al. Mantle cell lmyphoma. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris N, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J, Vardiman JW (eds). WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, 4th edn. WHO press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008, pp 229–232.

Jares P, Campo E . Advances in the understanding of mantle celll lymphoma. Br J Haematol 2008;142:149–165.

Salaverria I, Perez-Galan P, Colomer D, et al. Mantle cell lymphoma: from pathology and molecular pathogenesis to new therapeutic perspectives. Haematologica 2006;91:11–16.

Pruneri G, Valentini S, Bertolini F, et al. SP4, a novel anti-cyclin D1 rabbit monoclonal antibody, is a highly sensitive probe for identifying mantle cell lymphomas bearing the t(11;14)(q13;q32) translocation. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2005;13:318–322.

Fu K, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, et al. Cyclin D1-negative MCL: a clinicopathological study based on gene expression profiling. Blood 2006;106:4315–4321.

Spiegel S, Milstien S . Sphingosine-1-phosphate: an enigmatic signalling lipid. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2003;4:397–407.

Kihara A, Mitsutake S, Mizutani Y, et al. Metabolism and biological functions of two phosphorylated sphingolipids, sphingosine 1-phosphate and ceramide 1-phosphate. Prog Lipid Res 2007;46:126–144.

Liu Y, Wada R, Yamashita T, et al. Edg-1, the G protein-coupled receptor for sphingosine-1-phosphate, is essential for vascular maturation. J Clin Invest 2000;106:951–961.

Rosen H, Goetzl EJ . Sphingosine 1-phosphate and its receptors: an autocrine and paracrine network. Nat Rev Immunol 2005;5:560–570.

Hla T, Maciag T . An abundant transcript induced in differentiating human endothelial cells encodes a polypeptide with structural similarities to G-protein-coupled receptors. J Biol Chem 1990;265:9308–9313.

Rivera R, Chun J . Biological effects of lysophospholipids. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 2006;160:25–46.

Matloubian M, Lo CG, Cinamon G, et al. Lymphocyte egress from thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs is dependent on S1P receptor 1. Nature 2004;427:355–360.

Cinamon G, Matloubia M, Lesneski MJ, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 promotes B cell localization in the splenic marginal zone. Nat Immunol 2004;5:713–720.

Mandala SR, Hajdu J, Bergstrom E, et al. Alteration of lymphocyte trafficking by sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonists. Science 2002;296:346–349.

Akiyama T, Sadahira Y, Matsubara K, et al. Immunohistochemical detection of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 in vascular and lymphatic endothelial cells. J Mol Histol 2008;39:527–533.

Akiyama T, Hamazaki S, Monobe Y, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 is a useful adjunct for distinguishing vascular neoplasms from morphological mimics. Virchows Archiv 2009;454:217–222.

Straub AC, Klei LR, Stolz DB, et al. Arsenic requires sphingosine-1-phosphate type 1 receptors to induce angiogenic genes and endothelial cell remodeling. Am J Pathol 2009;174:1949–1958.

Sinha RK, Park C, Hwang IY, et al. B-lymphocytes exit lymph nodes through cortical lymphatic sinusoids by a mechanism independent of sphingosine-1-phosphate-mediated chemotaxis. Immunity 2009;30:434–446.

Nakamura N, Kuze T, Hashimoto Y, et al. Analysis of the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene variable region of 101 cases with peripheral B cell neoplasms and B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the Japanese population. Pathol Int 1999;49:595–600.

Rimokh R, Berger F, Bastard C, et al. Rearragement of CCND1 (BCL1/PRAD1)3′ untraslated region in mantle cell lymphomas and t(11q13)-associated leukemia. Blood 1994;83:3689–3696.

Jadayel DM, Lukas J, Nacheva E, et al. Potential role for concucurrent abnormalities of the cyclin D1, p16CDKN2 and p15CDKN2B genes in certain B cell non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Functional studies in a cell line (Granta 519). Leukemia 1997;11:64–72.

Jeon HJ, Kim CW, Yoshino T, et al. Establishment and characterization of a MCL cell line. Br J Haematol 1998;102:1323–1326.

Masuzawa M, Fujimura T, Hamada Y, et al. Establishment of a human hemangiosarcoma cell line (ISO-HAS). Int J Cancer 1999;81:305–308.

Goetzl EJ, Kong Y, Voice JK . Differential constitutive expression of functional receptors for lysophosphatidic acid by human blood lymphocytes. J Immunol 2000;64:4996–4999.

Swerdlow SH, Zukerberg LR, Yang WI, et al. The morphologic spectrum of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas with BCL1/cyclinD1 gene rearrangements. Am J Surg Pathol 1996;20:627–640.

Dorfman DM, Pinkus GS . Distinction between small lymphocytic and mantle cell lymphoma by immunoreactivity for CD23. Mod Pathol 1994;7:326–331.

Hummel M, Tamaru J, Kalvelage B, et al. Mantle cell (previously centrocytic) lymphomas express VH genes with no or very little somatic mutations like the physiologic cells of the follicle mantle. Blood 1994;84:403–407.

Zenz T, Mertens D, Döhner H, et al. Molecular diagnostics in chronic lymphocytic leukemia- pathogenetic and clinical implications. Leuk Lymphoma 2008;49:864–873.

Yatabe Y, Suzuki R, Tobinai K, et al. Significance of cyclin D1 overexpression for the diagnosis of mantle cell lymphoma: a clinicopathologic comparison of cyclin D1-positive MCL and cyclin D1-negative MCL-like B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2000;95:2253–2261.

Ek S, Dictor M, Jerkeman M, et al. Nuclear expression of the non–B-cell lineage Sox11 transcription factor identifies mantle cell lymphoma. Blood 2008;111:800–805.

Wang X, Asplund AC, Porwit A, et al. The subcellular Sox11 distribution pattern identifies subsets of mantle cell lymphoma: correlation to overall survival. Br J Haematol 2008;143:248–252.

Chae SS, Paik J, Furneaux H, et al. Requirement for sphingosine 1 phosphate receptor-1 in tumor angiogenesis demonstrated by in vivo RNA interference. J Clin Invest 2004;114:1082–1089.

Sadahira Y, Ruan F, Hakomori S, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate, a specific endogenous signaling molecule controlling cell motility and tumor cell invasiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1992;89:9686–9690.

Kurtova AV, Tamayo AT, Ford RJ, et al. Mantle cell lymphoma cells express high levels of CXCR4, CXCR5, and VLA-4 (CD49d): importance for interactions with the stromal microenvironment and specific targeting. Blood 2009;113:4604–4613.

Bayerl MG, Bruggeman RD, Conroy EJ, et al. Sphingosine kinase 1 protein and mRNA are overexpressed in non-Hodgkin lymphomas and are attractive targets for novel pharmacological interventions. Leuk Lymphoma 2008;49:948–954.

Brinkmann V, Davis MD, Heise CE, et al. The immune modulator FTY720 targets sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors. J Biol Chem 2002;277:21453–21457.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a Grant-in-aid (20590357) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan, and a project grant (20-209S) from the Kawasaki Medical School.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Presented in part at the 97th annual meeting of United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Denver, CO, March 1-7, 2008

Disclosure/conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nishimura, H., Akiyama, T., Monobe, Y. et al. Expression of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 in mantle cell lymphoma. Mod Pathol 23, 439–449 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2009.194

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2009.194

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

S1PR1/S1PR3-YAP signaling and S1P-ALOX15 signaling contribute to an aggressive behavior in obesity-lymphoma

Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2023)

-

Evaluation of S1PR1, pSTAT3, S1PR2, and FOXP1 expression in aggressive, mature B cell lymphomas

Journal of Hematopathology (2019)

-

Anti-leukemic activity of a four-plant mixture in a leukemic rat model

The Journal of Basic and Applied Zoology (2018)

-

Therapeutic potential of targeting sphingosine kinases and sphingosine 1-phosphate in hematological malignancies

Leukemia (2016)

-

Overexpression of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 and phospho-signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 is associated with poor prognosis in rituximab-treated diffuse large B-cell lymphomas

BMC Cancer (2014)