Abstract

Fifteen to thirty percent of cases with histologically confirmed CIN2–3 in cervical biopsies regress spontaneously (ie, show CIN1 or less in the follow-up cervical cone). The balance between immune-reactive cells from the host and high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) genotypes may provide a biological explanation for this phenomenon. We retrospectively studied 55 cases of CIN2–3 in a cervical biopsy with subsequent cervical cone to assess whether hrHPV genotypes (by AMPLICOR and Linear Array tests) CD4, CD8, CD25, CD138 and Foxp3 cells (by quantitative immunohistochemistry) in the cervical biopsies can predict regression (defined as CIN1 or less in the follow-up cone biopsy). Eighteen percent of the CIN2–3 cases regressed (median biopsy–cervical cone time interval: 12.0 weeks, range: 5.0–34.1 weeks). HPV-16 correlated with low CD8+ and high CD25+. None of the regressing CIN2–3 lesions contained HPV-16. The regressing CIN2–3 lesions had lower numbers of stromal CD138+ and higher numbers of stromal CD8+cells; higher stromal and intra-epithelial ratios of CD4+/CD25+ cells; higher ratios of CD8+/CD25+ cells and lower ratios of CD8+/CD4+, CD138+/Foxp3+ and CD25+/Foxp3+cells in the stroma. With multivariate survival analysis, stromal CD8+ cell numbers, CD4+/CD25+ cell ratios and CD138+ cell numbers are found to be independent regression predictors. In conclusion, in non-HPV-16 CIN2–3 lesions, assessing stromal immune cells can be a useful prognostic indicator of regression or persistence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

High-grade CIN (CIN2–3) is a frequent disease. The standard practice is to ablate all CIN2–3 lesions because if untreated, the majority of cases will persist.1, 2 In addition, after a long follow-up, 31.3% of the untreated cases will develop invasive squamous carcinoma, compared with <1% of the CIN3 cases that received conventional treatment.3 The latter can be associated with complications such as increased risk of preterm deliveries in patients treated with cervical conization.4 Conversely, 15–30% of CIN2–3 cases can regress spontaneously (ie, CIN1 or less detected in the follow-up cones).1 The prospective identification of this type of cases (ie, high-grade CIN that will regress spontaneously) is of great value as it will prevent unnecessary treatment. The crucial ingredients in the differences in the natural history of a CIN2–3 lesion (ie, regression or persistence) may relate to a patient-dependent balance between the genotypes of the human papillomavirus (HPV) and the patient's own immune response.

T-lymphocytes play a central role in both cell-mediated and humoral immunity by recognizing antigen bound to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) proteins and presented on the cell surface. CD4+ helper T-cells recognize antigen presented by class-II MHC and CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells recognize antigen presented by class-I MHC. Secretion of cytokines is responsible for the activation of two major subsets of CD4+ T-cells, Th1 or Th2 cells. The Th2 cells help antigen-primed B-lymphocytes to differentiate into plasma cells and secrete antibodies, whereas Th1 cells secrete interferon-α (IFN-γ) and generate cell-mediated immunity by activating macrophages, natural killer (NK) cells and cytotoxic CD8+ T-cells. Regulatory T-cells (T-regs) is a third category of T-cells characterized by coexpression of CD4, the constitutively expressing interleukin-2 (IL-2)-receptor chain CD255, 6 and the expression of the signature transcription factor Foxp3. These cells are thought to recognize self-antigens and prevent autoimmunity, but they also regulate responses to exogenous antigens and have been implicated in chronic and immunopathologic viral infections.7 Through contact-dependent mechanisms or IL-10 and TGF-β secretion, the T-regs are capable of suppressing the proliferation of other T-cells in the microenvironment.8, 9

Activation of native CD4+ cells drives the secretion of IL-2, followed by expression of CD25. This results in a positive feedback loop and production of full effector T-cells. IL-2 also maintains control of the effector T-cell responses by triggering a negative feedback loop, which drives the maintenance of the survival and population expansion of self-reactive Foxp3 T-regs, which in turn suppress the proliferation of antigen-presenting cells.10 To better understand the phenomenon of regression in high-grade CIN lesions, we analyzed whether the high-risk human papilloma virus (hrHPV) genotype, immunoreactive cells and T-regs can explain or predict regression in high-grade CIN lesions. This analysis was performed on cervical punch biopsies whereas regression (ie, CIN 1 or less) was assessed on the follow-up cones.

Materials and methods

This study has been approved by the Regional Medical Ethics Committee of Helse Vest, Norway (205/06), the Norwegian Social Science Data Service (5909/06) and the Norwegian Data Inspectorate (11512).

Patients

We retrospectively evaluated a total of 62 patients (median age: 33 years; range: 19–49 years) who underwent cervical conization at the Stavanger University Hospital during a 1-year period (July 2006–July 2007). All patients had an abnormal liquid-based cytology specimen collected as part of the routine cervical screening procedures. They were all positive for the AMPLICOR HPV DNA test and high-risk genotypes were detected by the Linear Array (LA) test. All patients had a cervical punch biopsy interpreted as CIN2–3 before conducting the conization procedure. The histologic diagnosis of the cervical punch biopsies and cervical cones was confirmed by a second pathologist who was unaware of the original diagnoses and clinical data. Upon this second review the cervical biopsies were diagnosed as CIN1 (1 case), CIN2 (7 cases) and CIN3 (54 cases), and the cervical cones as normal (9 cases), CIN1 (3 cases), CIN2 (8 cases) and CIN3 (42 cases). The final diagnoses were further confirmed by p16 and Ki67 immuno-quantitation. The cervical biopsy CIN1 case was excluded. Furthermore, in six of the cervical biopsies the CIN lesions in the paraffin blocks had been cut through and were therefore inadequate for immunohistochemical assessment, leaving 55 cases (10 regressions, 45 persistent) for the study.

AMPLICOR HPV and LA HPV Genotyping Test

The AMPLICOR HPV test (Roche Molecular Systems, Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) was used for HPV testing. This test permits simultaneous PCR amplification of HPV target DNA from 13 hrHPV genotypes and from β-globin DNA as a cellular control. A pool of HPV primers is designed to amplify the HPV DNA from 13 high-risk genotypes (16, 18, 31, 33 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59 and 68). PCR was performed using a GeneAmp PCR System 9700 with a gold block (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Oligonucleotide probes were hybridized to the amplified products and detected by colorimetric determination as described in the instruction manual (AMPLICOR- HPV test; Roche Molecular Systems, Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany).

The Roche LA–HPV genotyping test (Roche Molecular Systems, Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) was used to genotype the detected HPVs. This test uses biotinylated primers to define an approximately 450-bp sequence within the L1 region of the HPV genome. A pool of primers amplifies the HPV DNA from 37 HPV genotypes (6, 11, 16, 18, 26, 31, 33, 35, 39, 40, 42, 45, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 58, 59, 61, 62, 64, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 81, 82, 83, 84, 89 and IS39 (subtype of 82)). The group of 16 high-risk genotypes (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68, 73, 82 and IS39) includes the 13 genotypes targeted by the AMPLICOR test. Furthermore, groups of possible high-risk (26, 53 and 66), unclassified (55, 62, 64, 67, 69, 71, 83, 84 and 89) and low-risk (6, 11, 40, 42, 54, 61, 70, 72 and 81) genotypes were detected. An additional primer pair targeted the human β-globin gene to control for cell adequacy, DNA extraction and amplification. The amplification step was performed according to the Roche users' manual using the Applied Biosystems Gold-plated 96-Well GeneAmp PCR System 9700. After a denaturation step, the amplicons (75 μl) were hybridized to the array and detected using the recommended LA protocol. The LA HPV genotyping strips were manually interpreted by two observers using the Linear Array HPV Genotyping Test Reference Guide provided.

Immunohistochemistry

Antigen retrieval and dilution of the antibodies were optimized before the study started. Paraffin sections measuring 4 μm (adjacent to the hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections used for CIN grade assessment) were mounted onto Superfrost Plus slides (Menzel, Braunschweig, Germany) and dried overnight at 37 °C followed by 1 h at 60 °C. The sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through a graded series of alcohol solutions. Antigen retrieval was performed with a computerized retrieval system with highly accurate heating, cooling, temperature and time control (ImmunoPrep; Instrumec, Oslo, Norway). The sections were heated for 3 min at 110 °C followed by 10 min at 95 °C and cooled to 20 °C. TRIS (10 mM)/EDTA (1 mM) (pH 9) was used as retrieval buffer. Immunostaining was performed using an autostainer (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark; S3002). TBS (S1968) added at 0.05% Tween-20 (pH 7.6) was used as the rinse buffer. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using the peroxidase-blocking reagent S2001 (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) for 10 min and the sections were incubated with the monoclonal antibodies at the following dilutions: p16 (clone E6H4, CINtec Histology kit, ready to use; MTM laboratories, Heidelberg, Germany); Ki67 (clone MIB-1, 1:100; DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark; S3002); CD4 (clone 1F6, 1:20; Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK); CD8 (clone C8/144B, 1:50; DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark; S3002); CD25 (clone 4C9, 1:150; Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK); CD138 (clone B-B4, 1:200; Serotec, Kidlington, UK); Foxp3 (clone 236A/E7, 1:50; eBioscience, San Diego, USA). All the antibodies are well characterized regarding their specificity and sensitivity.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21

The DAKO antibody diluent S0809 was used and the immune complex was visualized by peroxidase/DAB (EnVision Detection System; DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark; K 5007) with incubation of Envision/HRP, rabbit mouse (ENV) for 30 min and DAB+chromogen for 10 min. The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated and mounted. Controls for the immunostainings were performed using normal cervical tissue control sections and positive normal cell compartments within the test sections. The section adjacent to the sections used for immunostainings was cut and stained with H&E to ensure the presence of the same CIN lesion in all test sections (‘sandwich technique’).

Image Analysis

The QPRODIT (version 6.1) interactive image analysis system (Leica, Cambridge, UK) was used for the measurements. In each case, the most representative area, that is, with the subjectively highest CIN grade, was carefully marked for the measurements. The length of any one epithelial strip demarcated was at least 30 μm. Special care was taken to avoid tangentially cut areas, recognizable by intraepithelial stromal islands, among other features, and squamous metaplastic endocervical gland areas under the surface of the covering squamous epithelium. Thus, the epithelial strip demarcated had a linear basal membrane parallel to the surface. Then, with a × 40 objective (numerical aperture=0.5), the lumen and the basal membrane of the most severely dysplastic epithelium were marked electronically. With a final monitor magnification of × 1400, the centre of each Ki-67-positive nucleus was marked interactively by the cursor. At least 75 positive nuclei were selected per case, which takes at most 5 min. The QPRODIT system automatically calculated a large number of quantitative features for each case: the distance from the nucleus to the basal membrane (DBM); the thickness (T) of the epithelium at the location of the nucleus indicated; the distance from the nucleus to the lumen (DL); the stratification index (SI) (DBM/T), which is the distance from the nucleus to the basal membrane divided by the thickness of the epithelium; the density of Ki-67-positive nuclei per 100 μm of basal membrane; and the percentage Ki-67-positive nuclei in the deep third, the middle third and the upper third of the epithelium.22

Semi-quantitative Scoring of the Immunohistochemical Staining of Biopsies from the Cervix

The extent and degree of immunopositivity was assessed by consensus scoring by two observers, using the same microscope (field of vision for the × 40 objective=0.52 mm, numerical aperture=0.65). For all the immunostainings, the most severely dysplastic area with the most intensive p16 staining was interpreted. Positivity for p16 staining in the upper and lower layers of the epithelium was defined as negative, weak or strong. The SI of CD138 was defined as the fraction with positive cells (membranous staining) measured from the basal membrane relative to the thickness of the whole epithelium at that location. The epithelium was subjectively divided into two layers, an upper and a lower half, and all biomarkers were assessed in each half separately as described previously.23 The stroma adjacent to the basal membrane was evaluated in a strip measuring 500 μm deep below the epithelial basal membrane. This was performed by using a × 40 objective with a field diameter of 520 μm and by viewing the membrane just visible in the outermost part of the field of vision. The localization of expression and the method for quantitation of the different biomarkers are summarized in Table 1.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS, version 15 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The continuous variables were divided into two different subgroups, using a threshold value assessed by receiver-operating curve (ROC) analysis (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium).24 Some continuous variables were used in stepwise regression analysis after log-normal transformation (=LN). The independent t-test and the Mann–Whitney U-test were used to compare the continuous variables and χ2-tests were used for the categorical immuno-quantitative variables. Binary logistic regression (Wald test) was performed to evaluate the effect of hrHPV genotype on different variables. To test the prognostic value of the variables, single (Kaplan–Meier) survival analyses using regression/no regression as the independent variable was performed and the between-group differences were tested using the log-rank test. Probabilities <0.05 were considered significant. The relative importance of potentially prognostic variables was tested using Cox proportional hazard analysis and expressed as a hazards ratio (HR) with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Multivariate survival analysis (Cox model) was performed to evaluate and compare the additional prognostic value of the variables with each other.

Results

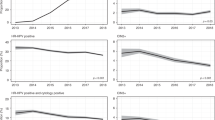

Regression was defined as a CIN2–3 in the cervical biopsy, with a subsequent cone diagnosed as CIN1 or less, as interpreted by two independent pathologists and confirmed by p16 and Ki67 immuno-quantitation. For the regression cases, eight biopsies were diagnosed as CIN3 and two as CIN2. The median cervical biopsy to cone time interval was 12.0 weeks (range: 5.0–34.1 weeks). There were no significant differences in the time interval (P=0.78), lesion size (P=0.35), age (P=0.94) or diagnosis of the cervical biopsies (P=0.70) for the regression-versus-persistent cases. HPV-16 or combined HPV-16/other high-risk genotypes, and non-HPV-16 high-risk genotypes, were found in the cytology specimens of all the cases. In 24% (13/55) of the cases, a single HPV type was detected and a combination of 2, 3 or more was seen in 76% (42/55) of the cases. All 10 cases with regression had an hrHPV genotype other than HPV-16, and none of the 18 HPV-16-containing CIN2–3 lesions regressed (P=0.02; Table 2). Three regression cases were infected with a single non-HPV-16 genotype whereas seven cases had multiple genotypes. Fisher's exact test indicated no significant association between single/multiple genotypes and regression/progression (P=0.44). Multivariate logistic regression showed that HPV genotype (as HPV-16, either alone or combined with other high-risk genotypes, versus all others) had an effect on the number and type of immune reactive cells. A low number of CD8+ (P=0.003) and a high number of CD25+ (P=0.009) correlated with HPV-16 (Figure 1) but not CD4+, CD138+ or Foxp3+.

The p16 staining intensity in the upper epithelium layer was stronger in the persistent cases (P=0.03). There was just significant indication that CIN lesions with non-HPV-16 infections are slightly more often negative for p16 staining in the superficial layer than the HPV-16-positive cases (24% versus 6%) (P=0.03). However, most of the non-HPV-16-infected, high-grade CINs are positive for p16 expression. Furthermore, p16 sensitivity in the deep layer is not different between the HPV-16-positive and the non-HPV-16-positive CIN lesions. For Ki-67 staining there were no significant differences (P=0.71) between the regression and persistent cases. The regressive CIN2–3 lesions had stronger epithelial expression of CD138+ and a lower number of stromal CD25+. The regression cases also showed a lower number of CD138-positive cells in the stroma, higher ratios of CD4+/CD25+ (Figure 2) and CD8+/CD25+ (Figure 3) cells; higher ratios of intraepithelial CD4+/CD25+ cells; and lower ratios of CD8+/CD4+, CD138+/Foxp3+ and CD25+/Foxp3+ cells in the stroma (Table 3). Foxp3-positive cells were found in the stromal microenvironment of all the CIN lesions, but the difference between the regression and persistent cases was small and not significant (P>0.10).

(a, b) Typical immunohistochemical images of the different features in regressive CIN3 lesions (in the left column) and persistent CIN3 lesions (in the right column). The CD25 positives are indicated by black arrows. For the regressive and the persistent CIN lesions, staining for Ki-67 and p16 shows similar features. The number of CD138 positives in the stroma (B-lymphocytes) were higher in the persistent cases (>37 per 1.0 mm of basal membrane), whereas the number of CD8 positives in the stroma (cytotoxic T-lymphocytes) was higher in the regressive cases (>113 per 1.0 mm of basal membrane). The numbers of CD4 positives in the stroma (T-helper cells) were not significantly different in the two groups, but the CD4+/CD25+ cell ratio was higher for the regression cases (>44 per 1.0 mm of basal membrane).

Multivariate (Cox model) survival analysis showed that low expression of stromal CD138+, high ratios of LN CD4+/CD25+ and high expression of stromal CD8+ were independent predictors for regression (Table 3 and Figure 3).

Discussion

It has been stated that regression of CIN2–3 lesions may be related to the balance between the HPV genotype and the patient's local immune response.25, 26, 27 In agreement with this, all the analyzed CIN2–3 lesions were infiltrated by various numbers of adaptive immune cells like CD138+ B-lymphocytes, CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocytes and CD4+ helper T-lymphocytes. Adaptive immune cells can recognize and specifically act against the E6 and E7 antigens expressed by HPV-infected cells28 to clear the infection. Conversely, persistence of an HPV infection can occur when an HPV-infected cell evades or suppresses this specific reaction. The E7 protein can influence the immune surveillance of HPV-containing tumor cells29 through binding and inactivation of the interferon-regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1) and downregulation of IFN-α. In this way HPV efficiently evades the innate immune system and delays the activation of the adapted immune response. Despite this, a successful immune response to HPV infections is established in some cases, characterized by cell-mediated immunity associated with lesion regression. However, in some cases this specific antigen-derived reaction can be suppressed by T-regs characterized by the expression of CD4/CD25 and Foxp3. Indeed the persistent cases had more CD25+ cells (possible T-regs), indicating that the specific immune response against the HPV infection was suppressed in these cases.

None of the regression cases were infected with HPV-16, either alone or in combination with other hrHPV types. This is in agreement with other findings showing that HPV-16-positive lesions are less likely to regress.30, 31 Interestingly this study showed that a low number of CD8+ cells and a high number of CD25+ cells correlated with HPV-16 infection. To facilitate immune evasion during viral replication, viruses use a wide range of mechanisms to inhibit antigen presentation. HPV-16, and HPV-18, E7 expression decreases the levels of cell-surface MHC-I molecules,32 thereby reducing the presentation of the viral antigens, which indicates that the balance between cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CD8+) and T-regulatory lymphocytes (CD25+) has an important role in the development of CIN2–3 lesions. Indeed, the regressive CIN2–3 lesions had higher ratios of CD4+/CD25+ cells both in the stroma and in the epithelium, and higher CD8+/CD25+ cell ratios in the stroma, thereby enabling antigen-derived specific immune response in these cases. Furthermore, no correlation was found between regression and Foxp3+ cells, but the ratios of CD25+/Foxp3+ cells were lower in the regression cases, illustrating that the proportion of CD25+ cells, which are also Foxp3+, were lower in these cases.

The higher number of CD138+ cells in the stroma of the persistent cases, representing mature B-cells,11 might seem paradoxical as these cells act as antigen-presenting cells and are highly active in the humoral immune reaction against microbial infections. Conversely, interactions between innate and adaptive immune cells can be disturbed during chronic inflammation and adaptive immune responses can cause an ongoing activation of the innate immune cells.33 Studies of transgenic mouse models support the hypothesis that enhanced local humoral and innate immune activation combined with suppressed cellular immunity and reduced cytotoxic T-cell antitumor immunity can promote early carcinogenesis.34, 35 Furthermore, a persistent and excessive innate immune reaction can promote angiogenesis and tissue remodeling by the production of growth factors, cytokines, chemokines and matrix metalloproteinases, thereby stimulating carcinogenesis even further.

The accumulation of effector T-cells and activated B-cells in the tumor may be evidence of systemic immune tolerance by the host as they seem to be largely ineffective in arresting tumor growth. The active strategy adopted by hrHPV E6 and E7 for evading the immune response by reducing the levels of surface MHC class-I molecules is responsible for suppression of the T-cell-mediated immune response and NK cell recognition by reducing the presentation of the viral and tumor antigens.32 This might lead to chronic disturbance of the tissue homeostasis and an imbalance between cytotoxic T-lymphocytes and suppressor T-cells, as shown by lower ratios of CD8+/CD25+ cells and favoring cancer development.

Co-infection with other sexually transferred diseases is believed to be a risk factor for developing CIN. Infections by Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis and Trichomonas vaginalis have been found to be associated with persistence of HPV. In a group of young African-American women with a median age of 16 years (range: 13–19 years), co-infection with C. trachomatis but not N. gonorrhoea or T. vaginalis, and multiple HPV types were found to be independently associated with the risk for persistence of hrHPV. No association was found with the detection of low- or high-grade cervical lesions.36 Infection with C. trachomatis and HPV is highly prevalent in very young women although the peak for age-specific incidence rate of cervical cancer is 39 years.37 In line with a large randomized38 trial based on the high number of false positives among younger women, the Norwegian screening program has a strategy for starting HPV testing at age 25. Despite the higher average age for CIN lesions as compared with the target group for testing positive with C. trachomatis, it would be interesting to study if a co-infection has an influence on the local immune response in CIN lesions. A change in the vaginal flora could also be an interesting cofactor and might be one explanation to the second age-related incidence peak (50–65) observed in many populations.39

Although negative p16 immunostaining in the superficial layer is slightly more often associated with the non-HPV-16 subtype, most of the non-HPV-16 cases had weak or strong immunostaining in the superficial layer and some HPV-16 high-grade CINs also were negative. Thus, negative p16 in the superficial epithelial layers cannot be used as a definitive indication for non-HPV-16 infection. In agreement with other studies, p16 expression is not a good predictor for the outcome of high-grade CIN lesions.40, 41

The results of this current study are interesting and potentially clinically relevant. In high-grade CIN lesions, HPV-16 is associated with decreased numbers of CD8+ and increased numbers of CD25+ immunoreactive cells. Most importantly, low CD138+ and high CD8+ cell numbers in combination with high ratios of CD4+/CD25+ and CD8+/CD25+ immunoreactive cells correlates with regression. In addition, regression is unlikely to occur in high-grade CIN associated with HPV-16.

These alleged prognostic indicators of regression need to be compared with epithelial molecular biomarkers such as p16, Ki-67, retinoblastoma protein (pRb) and tumor-suppressor protein (p53), which have been reported to have a predictive value for progression of CIN1 and regression of CIN2–3 lesions.42 The known risk factors related to regression/persistence like age at the time of diagnosis, lesion size and the time interval between biopsy and cone were not significant in this limited-size study.

References

Ostor A . The natural history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a critical review. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1993;12:186–192.

Horner MJ RL, Krapcho M, Neyman N, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1975–2006Cancer Statistics Branch of the NC 2009 [cited 2009 Based on November 2008 SEER data submission]. Available fromhttp://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006/.

McCredie MR, Sharples KJ, Paul C, et al. Natural history of cervical neoplasia and risk of invasive cancer in women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2008;9:425–434.

Albrechtsen S, Rasmussen S, Thoresen S, et al. Pregnancy outcome in women before and after cervical conisation: population based cohort study. BMJ 2008;337:a1350.

Maloy KJ, Powrie F . Fueling regulation: IL-2 keeps CD4+Treg cells fit. Nat Immunol 2005;6:1071–1072.

von Boehmer H . Mechanisms of suppression by suppressor T cells. Nat Immunol 2005;6:338–344.

Rouse BT, Suvas S . Regulatory cells and infectious agents: detentes cordiale and contraire. J Immunol 2004;173:2211–2215.

Strauss L, Whiteside TL, Knights A, et al. Selective survival of naturally occurring human CD4+CD25+Foxp3+regulatory T cells cultured with rapamycin. J Immunol 2007;178:320–329.

Bergmann C, Strauss L, Zeidler R, et al. Expansion and characteristics of human T regulatory type 1 cells in co-cultures simulating tumor microenvironment. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2007;56:1429–1442.

Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Gavin MA, et al. A function for interleukin 2 in Foxp3-expressing regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol 2005;6:1142–1151.

Carbone A, Gloghini A, Gattei V, et al. Reed–Sternberg cells of classical Hodgkin's disease react with the plasma cell-specific monoclonal antibody B-B4 and express human syndecan-1. Blood 1997;15:3787–3794.

Iijima W, Ohtani H, Nakayama T, et al. Infiltrating CD8+T cells in oral lichen planus predominantly express CCR5 and CXCR3 and carry respective chemokine ligands RANTES/CCL5 and IP-10/CXCL10 in their cytolytic granules: a potential self-recruiting mechanism. Am J Pathol 2003;163:261–268.

Key G, Becker MH, Baron B, et al. New Ki-67-equivalent murine monoclonal antibodies (MIB 1–3) generated against bacterially expressed parts of the Ki-67 cDNA containing three 62 base pair repetitive elements encoding for the Ki-67 epitope. Lab Invest 1993;68:629–636.

Klaes R, Friedrich T, Spitkovsky D, et al. Overexpression of p16(INK4A) as a specific marker for dysplastic and neoplastic epithelial cells of the cervix uteri. Int J Cancer 2001;92:276–284.

Mason DY, Cordell JL, Gaulard P, et al. Immunohistological detection of human cytotoxic/suppressor T cells using antibodies to a CD8 peptide sequence. J Clin Pathol 1992;45:1084–1088.

Persson A, Hober S, Uhlen M . A human protein atlas based on antibody proteomics. Curr Opin Mol Ther 2006;8:185–190.

Roncador G, Brown PJ, Maestre L, et al. Analysis of FOXP3 protein expression in human CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells at the single-cell level. Eur J Immunol 2005;35:1681–1691.

Waldmann TA . The multi-subunit interleukin-2 receptor. Annu Rev Biochem 1989;58:875–911.

Wang SS, Trunk M, Schiffman M, et al. Validation of p16INK4a as a marker of oncogenic human papillomavirus infection in cervical biopsies from a population-based cohort in Costa Rica. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2004;13:1355–1360.

Wijdenes J, Vooijs WC, Clement C, et al. A plasmocyte selective monoclonal antibody (B-B4) recognizes syndecan-1. Br J Haematol 1996;94:318–323.

Williamson SL, Steward M, Milton I, et al. New monoclonal antibodies to the T cell antigens CD4 and CD8 Production and characterization in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue. Am J Pathol 1998;152:1421–1426.

Kruse AJ, Baak JP, de Bruin PC, et al. Ki-67 immunoquantitation in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN): a sensitive marker for grading. J Pathol 2001;193:48–54.

Kruse AJ, Skaland I, Munk AC, et al. Low p53 and retinoblastoma protein expression in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 lesions is associated with coexistent adenocarcinoma in situ. Hum Pathol 2008;39:573–578.

Soreide K . Receiver-operating characteristic curve analysis in diagnostic, prognostic and predictive biomarker research. J Clin Pathol 2009;62:1–5.

Kobayashi A, Weinberg V, Darragh T, et al. Evolving immunosuppressive microenvironment during human cervical carcinogenesis. Mucosal Immunol 2008;1:412–420.

Wang SS, Zuna RE, Wentzensen N, et al. Human papillomavirus cofactors by disease progression and human papillomavirus types in the study to understand cervical cancer early endpoints and determinants. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009;18:113–120.

de Boer MA, Jordanova ES, van Poelgeest MI, et al. Circulating human papillomavirus type 16 specific T-cells are associated with HLA class I expression on tumor cells, but not related to the amount of viral oncogene transcripts. Int J Cancer 2007;121:2711–2715.

Evans EM, Man S, Evans AS, et al. Infiltration of cervical cancer tissue with human papillomavirus-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes. Cancer Res 1997;57:2943–2950.

Um SJ, Rhyu JW, Kim EJ, et al. Abrogation of IRF-1 response by high-risk HPV E7 protein in vivo. Cancer Lett 2002;179:205–212.

Trimble CL, Piantadosi S, Gravitt P, et al. Spontaneous regression of high-grade cervical dysplasia: effects of human papillomavirus type and HLA phenotype. Clin Cancer Res 2005;11:4717–4723.

Castle PE, Schiffman M, Wheeler CM, et al. Evidence for frequent regression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia-grade 2. Obstet Gynecol 2009;113:18–25.

Bottley G, Watherston OG, Hiew YL, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus E7 expression reduces cell-surface MHC class I molecules and increases susceptibility to natural killer cells. Oncogene 2008;27:1794–1799.

de Visser KE, Eichten A, Coussens LM . Paradoxical roles of the immune system during cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer 2006;6:24–37.

de Visser KE, Korets LV, Coussens LM . De novo carcinogenesis promoted by chronic inflammation is B lymphocyte dependent. Cancer Cell 2005;7:411–423.

Tan TT, Coussens LM . Humoral immunity, inflammation and cancer. Curr Opin Immunol 2007;19:209–216.

Samoff E, Koumans EH, Markowitz LE, et al. Association of Chlamydia trachomatis with persistence of high-risk types of human papillomavirus in a cohort of female adolescents. Am J Epidemiol 2005;162:668–675.

Bosch FX, Lorincz A, Munoz N, et al. The causal relation between human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. J Clin Pathol 2002;55:244–265.

Kulasingam SL, Rajan R, St Pierre Y, et al. Human papillomavirus testing with Pap triage for cervical cancer prevention in Canada: a cost-effectiveness analysis. BMC Med 2009;7:69.

Chan PK, Chang AR, Yu MY, et al. Age distribution of human papillomavirus infection and cervical neoplasia reflects caveats of cervical screening policies. Int J Cancer 2010;126:297–301.

Guedes AC, Brenna SM, Coelho SA, et al. p16 (INK4a) expression does not predict the outcome of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2007;17:1099–1103.

Ishikawa M, Fujii T, Saito M, et al. Overexpression of p16 INK4a as an indicator for human papillomavirus oncogenic activity in cervical squamous neoplasia. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2006;16:347–353.

Kruse AJ, Skaland I, Janssen EA, et al. Quantitative molecular parameters to identify low-risk and high-risk early CIN lesions: role of markers of proliferative activity and differentiation and Rb availability. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2004;23:100–109.

Acknowledgements

This study was made possible by grants from Helse Vest (project number 507030) and the Stavanger University Hospital (number 2009/632), and a grant from the Stichting Bevordering Diagnostische Morfometrie (Middelburg, the Netherlands). We thank Anne Elin Varhaugvik, Britt Fjæran and Bianca Van Diermen for technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Øvestad, I., Gudlaugsson, E., Skaland, I. et al. Local immune response in the microenvironment of CIN2–3 with and without spontaneous regression. Mod Pathol 23, 1231–1240 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2010.109

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2010.109

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The value of cytokine levels in triage and risk prediction for women with persistent high-risk human papilloma virus infection of the cervix

Infectious Agents and Cancer (2019)

-

A prospective cohort study to evaluate immunosuppressive cytokines as predictors of viral persistence and progression to pre-malignant lesion in the cervix in women infected with HR-HPV: study protocol

BMC Infectious Diseases (2018)

-

Vaginal drug delivery for the localised treatment of cervical cancer

Drug Delivery and Translational Research (2017)

-

Determination of malignant potential of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

Tumor Biology (2016)

-

Cell mediated immunity against HPV16 E2, E6 and E7 peptides in women with incident CIN and in constantly HPV-negative women followed-up for 10-years

Journal of Translational Medicine (2015)