Abstract

Lobular neoplasia has been traditionally recognized as a marker of increased risk for subsequent breast carcinoma development; however, molecular studies suggest that it also behaves in a non-obligate precursor manner. We do not know, as yet, how to identify the subgroup of cases that is most likely to progress, but the epidemiological data would indicate that this progression occurs after a long period of time. Thus, the current approach of conservative management of these lesions when identified in excision specimens is justified. Recently, several variants of lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), most notably pleomorphic LCIS, have been recognized and these can be difficult to differentiate from ductal carcinoma in situ. Application of strict diagnostic criteria and the judicial use of immunohistochemistry, particularly E-cadherin, can be helpful in this differential diagnosis. Another challenging issue is the management of lobular neoplasia when diagnosed on core biopsy. This controversial issue will be discussed in detail. The goals of this review are (1) to describe the morphological criteria used to diagnose the spectrum of lobular neoplastic lesions, including atypical lobular hyperplasia, LCIS and variants of LCIS; (2) to discuss the data exploring the biological potential of lobular neoplasia from an epidemiological and molecular viewpoint; and (3) to outline the recommendations for management of lobular neoplasia when encountered in core biopsies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The term ‘lobular carcinoma in situ’ (LCIS) was first coined by Foote and Stewart1 over 65 years ago. Their description of the morphological appearance of the disease still holds true today: an entity composed of a monomorphic population of dyshesive cells expanding the terminal duct lobular unit. Almost 40 years after this first description of LCIS, Haagensen et al2 published their own experience with this disease and concluded that ‘lobular neoplasia’ was a more appropriate term for this lesion as few cases appeared to progress to invasive carcinoma. With increasing recognition of LCIS, it became apparent that less well-developed forms were more frequently seen in the breast. Page et al used the term atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH) for these lesions.3, 4 In practice today, the term lobular neoplasia refers to both ALH and LCIS. Lobular neoplastic lesions have also been classified using an alternative nomenclature: lobular intraepithelial neoplasia,5 although this classification is used less frequently in clinical practice.

There has been much debate in the literature regarding the natural history of lobular neoplastic lesions.6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Epidemiological studies have clearly shown lobular neoplasia as a marker of increased risk.11, 12, 13, 14 However, in recent years, there is increasing evidence that LCIS may also act as a non-obligate precursor in the progression to invasive carcinoma.7, 15, 16, 17

Clinical features

Lobular neoplastic lesions (ALH and LCIS) are often multicentric and bilateral.1, 18 They occur predominantly in premenopausal women, with most cases being diagnosed in women between 40 and 50 years of age.13, 19, 20, 21, 22 They are clinically occult, and although they are often also mammographically silent, a significant minority of lobular neoplasia cases diagnosed on core biopsy have associated microcalcifications.23, 24, 25, 26

Data derived from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program27 have shown that the age-adjusted, age-specific rates of LCIS among women in the United States has increased fourfold between the late 70s (0.9 per 100 000 person years) and late 90s (3.2 per 100 000 person years). Women aged between 50 and 59 years experienced the greatest absolute increase in incidence from 1978 to 1998. This rising incidence was not seen in premenopausal women or in women over 70 years of age.22

Epidemiology

Although the morphological distinction between ALH and LCIS is quantitative and based on an arbitrarily set threshold, the epidemiological studies clearly indicate a significantly higher relative risk of subsequent carcinoma development associated with LCIS (eight- to ninefold) compared with ALH (four- to fivefold).2, 3, 12, 28 The extent of LCIS in the breast does not seem to significantly affect risk.11, 29, 30 LCIS confers ∼15% absolute risk of developing breast cancer at 15 years, but a significant number of subsequent carcinomas occur more than 15 years after a diagnosis of LCIS.2, 12, 19, 20, 21 Although lobular neoplasia has been linked to an increased risk of subsequent carcinoma in either breast,12, 13, 21 several studies have shown a higher, although not always statistically significant, risk in the ipsilateral breast.3, 14, 17, 20, 30, 31 Cancer risk in ALH seems to vary with patient age; an initial diagnosis of ALH in postmenopausal women has been associated with a lower risk of subsequent carcinoma development than in premenopausal women.3, 14, 17, 31

The majority of invasive carcinomas that subsequently occur in cases of lobular neoplasia are ductal, no special type. But invasive lobular carcinomas constitute up to 45% of subsequent carcinomas;12, 21, 30, 32 this is in sharp contrast to the expected rate (5–14%) of invasive lobular carcinomas in the general population.

Histopathology

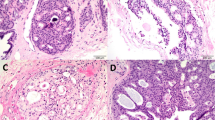

Both ALH and LCIS are defined using the criteria of Page and colleagues3, 33 by a population of cells that are small, round, monomorphic, dyshesive with an increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio; ALH is diagnosed when <50% of the acini in the affected terminal duct lobular unit are involved by the lobular proliferation and these cells do not completely occlude the lumen or produce marked distension of the acini (Figure 1). LCIS is diagnosed when >50% of the acini in the affected terminal duct lobular unit are completely filled and distended by the cellular proliferation (Figure 2). In practice, ALH and LCIS often coexist (Figure 3), and for this reason, along with the fact that it can be difficult to differentiate ALH from LCIS, some authorities would advocate using the term lobular neoplasia for both lesions. Intracytoplasmic vacuoles are often present in both ALH and LCIS and can be a prominent feature. Pagetoid extension along ducts producing a ‘clover leaf’ appearance is not uncommon. Although the majority of cells comprising these lobular neoplastic lesions are uniform with bland nuclei and scant cytoplasm (referred to as ‘type A’ cells2), in some cases the cells are somewhat larger with more cytoplasm and show mild to moderate nuclear atypia (‘type B’ cells) (Figure 4). Lesions composed of either cell types are referred to as ‘classic’ lobular neoplasia and should be distinguished from variants of LCIS (see below).

ALH: (a and b) Morphologically ALH and LCIS are composed of small, regular round, loosely cohesive cells originating in the terminal duct lobular unit. The diagnosis of ALH is made when the acini are only partially filled by these cells; if there is distension present, <50% of the acini are involved.

Variants of LCIS

Several variants of LCIS have been recognized. These include pleomorphic LCIS, pleomorphic apocrine LCIS, LCIS with comedo necrosis and carcinoma in situ with mixed ductal and lobular features. Clear cell and signet ring cell variants of LCIS have also been described.

PLCIS

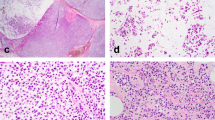

Pleomorphic LCIS (PLCIS) was first identified as a distinct entity by Eusebi et al34 in 1992. The few reports that have been published since then have described cases of pleomorphic LCIS associated with invasive lobular carcinoma.35, 36, 37 Sneige et al38 described in detail the morphological features of pleomorphic LCIS not associated with invasive lobular carcinoma. The cytological appearances of these cells are quite different to those of classic LCIS. Although the cells appear dyshesive as in classic LCIS, they exhibit a greater degree of nuclear pleomorphism and usually contain abundant cytoplasm (Figure 5). Occasionally, the cytoplasm can appear eosinophilic and finely granular, giving the cells an apocrine appearance (pleomorphic apocrine LCIS) (Figure 6). Central, comedo necrosis and calcifications are quite commonly associated with this lesion and can be confused with comedo ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) (Figure 7).

Pleomorphic LCIS (PLCIS). (a) Low power shows spaces expanded by a dyshesive population of cells with central necrosis. (b) High power shows a greater degree of nuclear pleomorphism than is seen in classic LCIS (see Figure 4), but the cells show a similar degree of dyshesiveness as in classic LCIS. Intracytoplasmic vacuoles are evident.

LCIS with Comedo Necrosis

Lobular carcinoma with comedo necrosis39 has recently been described. Before the widespread use of E-cadherin, such cases were categorized as mixed ductal and lobular carcinoma30, 40, 41 or carcinoma in situ with indeterminate features.42 These lesions are comprised of identical cells to those of classic LCIS; namely, small, uniform cells with intracytoplasmic lumina and a dyshesive growth pattern, but in addition, contain central areas of comedo necrosis (Figures 8a and b). Calcifications are often associated with the areas of necrosis (Figures 8c and d). One study of 18 cases reported a strong association (67%) with invasive carcinoma. In all, 11 of these invasive carcinomas (92%) were either pure invasive lobular carcinomas or had focal lobular features.39

LCIS with comedo necrosis. (a) The degree of nuclear pleomorphism in this case is less than that seen in PLCIS, despite being associated with central necrosis. (b) E-cadherin in this shows no immunoreactivity. (c) Another case of LCIS with central necrosis and abundant calcifications. (d) E-cadherin in this case is also negative.

In Situ Carcinoma with Mixed Ductal and Lobular Features

Some in situ lesions show features that resemble both LCIS and DCIS. These cases often are comprised of small, monotonous cells typical of LCIS, but appear more cohesive. Alternatively, these cases may resemble DCIS architecturally with the formation of microacinar-like structures but show dyshesion typical of LCIS (Figure 9). E-cadherin immunohistochemistry may show heterogeneous staining is such cases; in one study, roughly one third of cases were negative for E-cadherin, one third were positive and one third had both positive and negative cells within the same lobular unit.42 This latter pattern of staining should be differentiated from staining of residual benign epithelial cells in a space filled by lobular neoplastic cells (Figure 10).

Immunophenotype

Although both classic lobular neoplasia and the variants of LCIS are almost uniformly positive for hormone receptors (estrogen and progesterone) and negative for E-cadherin,42, 43, 44, 45 (Figure 8) there are important differences in their immunophenotype. Classic LCIS and LCIS with comedo necrosis are negative for HER2 protein overexpression/gene amplification, lack p53 mutations and have a low Ki67 labeling index. Conversely, pleomorphic LCIS may show HER2 protein overexpression/gene amplification (particularly if associated with invasive carcinoma), may show p53 positivity and has a moderate to high Ki67 labeling index.38, 46 In addition, pleomorphic LCIS is often positive with gross cystic disease fluid protein-15, not surprisingly as these lesions often display apocrine features. High molecular weight cytokeratin positivity has been reported as a useful adjunct in differentiating morphologically ambiguous in situ lesions into ductal or lobular categories.47 However, others have failed to reproduce these findings. Indeed, positive staining seen with the antibody 34betaE12 in lobular neoplasia may in fact be related to the antigen retrieval process.48 In addition, although E-cadherin is very useful as an adjunct in differentiating ductal from lobular lesions, morphologically unequivocal cases of LCIS and invasive lobular carcinoma have been shown to demonstrate focal E-cadherin positivity.49, 50

Dabbs et al51, 52 recently reported the utility of p120-catenin in both classic and pleomorphic variants of LCIS. Characteristically, this antibody is diffusely localized to the cytoplasm in cases of lobular neoplasia, whereas in ductal lesions it remains localized to the membrane.

Differential diagnosis

Low-grade DCIS forming a solid growth pattern can be very difficult to differentiate from classic LCIS, even in excisional biopsy specimens. The presence of a dyshesive growth pattern and prominent intracytoplasmic vacuoles favors a diagnosis of lobular neoplasia (Figure 4). On the other hand, the presence of microacinar formations in this setting would support a diagnosis of DCIS. (Figure 11) E-cadherin immunohistochemistry can be particularly helpful in such cases (Figure 12).

Myoepithelial cells may be confused with lobular neoplasia, particular when these cells extend in a pagetoid manner into ducts and show abundant clear cytoplasm. The morphological characteristics of the myoepithelial cell, particularly the small, pyknotic-appearing nucleus and the clear cytoplasm, should help with this differential diagnosis.

Pleomorphic LCIS is very easily confused with high-grade DCIS, particularly when there is associated central necrosis and calcifications. The dyshesive appearance of the cells is helpful in making this diagnosis, as is the lack of E-cadherin staining (Figure 13).

Lobular neoplasia extending into sclerosing adenosis can be challenging, especially on core biopsies. The use of myoepithelial markers, such as smooth muscle myosin heavy chain or p63, can be very helpful in differentiating this process from an invasive carcinoma.

Molecular studies

Much has been discovered about the molecular genetics of lobular neoplasia in recent years. Most of these studies have focused on in situ lobular lesions associated with adjacent invasive lobular carcinoma. Studies investigating loss of heterozygosity, E-cadherin expression and mutations in the E-cadherin gene, CDH1, have shown a relationship between LCIS and invasive lobular carcinoma.43, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57 The CDH1 gene is inactivated in both in situ and invasive lobular carcinomas by genetic (inactivating mutations of deletions) or epigenetic (promoter methylation) mechanisms.43, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58 E-cadherin is a cell adhesion molecule that forms complexes with β-, γ-, α-catenins and p120-catenin. Loss of E-cadherin-mediated cell adhesion is believed to account for the dyshesive nature of lobular neoplasia and invasive lobular carcinoma. Invasive lobular carcinomas with adjacent LCIS not only lose E-cadherin, but have also been shown to simultaneously lose β-, γ- and α-catenin protein expression.52 Aberrant cytoplasmic localization of p120-catenin (which may have a role in mediating the oncogenic effects of E-cadherin loss) has also been shown to characterize lobular neoplasia.52, 58

The development of powerful molecular techniques such as comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) has led to further discoveries in the molecular genetics of lobular neoplasia.16, 59 Lu et al59 using conventional chromosomal CGH (cCGH) found alterations at chromosomes 6, 16, 17 and 22. These alterations were found in similar frequency in LCIS and ALH, and therefore, based on these chromosomal CGH profiles, ALH and LCIS were suggested to represent the same genetic stage of development. The alterations found by Lu et al59 in lobular neoplasia using cCGH were also identified and further refined by a study using array CGH.16 Altered regions in this study included loss at 16p11.2-p11.1 and loss at 22q11.1. Genes within regions of alteration found in both ALH and LCIS were identified to be involved in the process of luminal morphogenesis.16, 60 Both ALH and LCIS showed loss of 16q21-q23.1 (E-cadherin gene, CDH1;16q21.1); this region was lost in all matched pairs of LCIS and invasive lobular carcinoma in another study using array CGH.61

There have been few molecular genetic studies of PLCIS.46, 62, 63 Although PLCIS shows the characteristic molecular genetic changes of classic lobular neoplasia (gain of 1q and deletion of 16q along with E-cadherin inactivation), this variant of lobular neoplasia also shows HER2/neu amplification, MYC amplification, deletion of 13q and gain of 20q.46, 62

The molecular data described above suggest that ALH/LCIS behaves in a non-obligate precursor manner. Loss of 16q and gain at 1q in lobular neoplasia points to the possible progression toward a low-grade invasive phenotype, given the frequency of these alterations in low-grade invasive breast cancer.64 Taken together, however, the molecular genetic and clinicopathological data support lobular neoplasia acting both as a precursor lesion and as a risk indicator for subsequent carcinoma. We cannot, as yet, predict which lobular neoplastic lesions are likely to progress. Further studies are needed to understand and identify the subset of lobular neoplastic lesions that have the highest likelihood of progressing to invasive carcinoma.

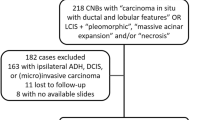

Management of lobular neoplasia in core biopsies

The management of lobular neoplasia on core biopsy has received increased attention in the literature over recent years. Over 30 studies have addressed this issue since 1999.23, 24, 25, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93 Upgrade rates to either DCIS or invasive carcinoma in as many as 40% of cases have been reported, but these studies showed variability in the degree of pathological–radiological correlation and variations in imaging techniques including the number and caliber of cores taken, and they also included variants of lobular neoplasia.94, 95

Nevertheless, there is a general consensus that excision should be performed in cases of lobular neoplasia identified on core biopsy when the following conditions apply:

-

1)

when another lesion that would in itself lead to excision, such as atypical ductal hyperplasia, is also present in the core biopsy;

-

2)

when there is discordance between the radiological and pathological findings;

-

3)

when there is an associated mass lesion or area of architectural distortion;

-

4)

if the lesion shows indeterminate features between a ductal and lobular proliferation; and

-

5)

if the morphology is consistent with pleomorphic LCIS or other variants of LCIS.81, 96

However, some recent studies have shown that classic lobular neoplasia as the sole lesion identified on core biopsy has been associated with either DCIS or invasive carcinoma in 10–27% of cases.65, 74, 80, 82, 89 These studies were limited by the small numbers of cases included and by their retrospective nature, which may have lead to selection bias with respect to the patients who underwent immediate excision. More recently, three studies92, 93, 97 have reported much lower rates of upgrades (1–3%). These studies included relatively large numbers of patients with lobular neoplasia on core biopsy who had immediate excision; larger volumes of tissue were sampled and there was meticulous attention paid to pathological–radiological correlation. The upgrade rates in two of these studies92, 93 would have been much higher if their cases showing discordant pathological and imaging findings had been included. Of particular note in one of these studies93 is that, although few of these women with lobular neoplasia on core biopsy had DCIS or invasive carcinoma in the subsequent excision, up to 30% of these women developed DCIS or invasive carcinoma in either the ipsilateral or contralateral breast before or after the core biopsy. Many of the subsequent ipsilateral carcinomas occurred in sites not related to the previous core biopsy.

In summary, the data clearly show that lobular neoplasia can behave both as a high-risk lesion and as a non-obligate precursor. But given the long latency period to progression, conservative management of these lesions when identified in excision specimens remains the mainstay of treatment. We are increasingly recognizing variants of lobular neoplasia, and although their management at present is identical to that of DCIS, it is important to separate these lesions from DCIS so that we can learn more about their biological behavior. Finally, the management of lobular neoplasia when diagnosed on core biopsy remains a controversial issue. But there is general agreement that patients who have a diagnosis of a variant of LCIS on core biopsy should undergo immediate excision. On the other hand, the evidence does not support routine excision following a diagnosis of classic lobular neoplasia on core biopsy when there is complete pathological–mammographic correlation and the suspicious area on imaging has been adequately sampled. Although women with classic lobular neoplasia on core biopsy have a low risk of having a carcinoma at the site of the biopsy, there is an increased risk of developing a subsequent carcinoma in either the ipsilateral or contralateral breast. Thus, these women need close ongoing follow-up.

References

Foote F, Stewart F . Lobular carcinoma in situ: a rare form of mammary cancer. Am J Pathol 1941;17:491–496.

Haagensen CD, Lane N, Lattes R, et al. Lobular neoplasia (so-called lobular carcinoma in situ) of the breast. Cancer 1978;42:737–769.

Page DL, Dupont WD, Rogers LW, et al. Atypical hyperplastic lesions of the female breast. A long-term follow-up study. Cancer 1985;55:2698–2708.

Dupont WD, Page DL . Risk factors for breast cancer in women with proliferative breast disease. N Engl J Med 1985;312:146–151.

Tavassoli FA . Lobular neoplasia. In: Tavassoli FA (ed). Pathology of the Breast, 2nd edn. McGraw-Hill: New York, 1999, pp 373–400.

Lishman SC, Lakhani SR . Atypical lobular hyperplasia and lobular carcinoma in situ: surgical and molecular pathology. Histopathology 1999;35:195–200.

Simpson PT, Gale T, Fulford LG, et al. The diagnosis and management of pre-invasive breast disease: pathology of atypical lobular hyperplasia and lobular carcinoma in situ. Breast Cancer Res 2003;5:258–262.

Schnitt SJ, Morrow M . Lobular carcinoma in situ: current concepts and controversies. Semin Diagn Pathol 1999;16:209–223.

Page DL, Simpson JF . What is atypical lobular hyperplasia and what does it mean for the patient? J Clin Oncol 2005;23:5432–5433.

Reis-Filho JS, Pinder SE . Non-operative breast pathology: lobular neoplasia. J Clin Pathol 2007;60:1321–1327.

Bodian CA, Perzin KH, Lattes R . Lobular neoplasia. Long term risk of breast cancer and relation to other factors. Cancer 1996;78:1024–1034.

Chuba PJ, Hamre MR, Yap J, et al. Bilateral risk for subsequent breast cancer after lobular carcinoma-in-situ: analysis of surveillance, epidemiology, and end results data. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:5534–5541.

Haagensen CD, Bodian CA, Haagensen Jr DE . Breast Cancer Risk and Detection. WB Saunders: Philadelphia, 1981.

Collins LC, Baer HJ, Tamimi RM, et al. Magnitude and laterality of breast cancer risk according to histologic type of atypical hyperplasia: results from the Nurses’ Health Study. Cancer 2007;109:180–187.

Lakhani SR . In-situ lobular neoplasia: time for an awakening. Lancet 2003;361:96.

Mastracci TL, Shadeo A, Colby SM, et al. Genomic alterations in lobular neoplasia: a microarray comparative genomic hybridization signature for early neoplastic proliferation in the breast. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2006;45:1007–1017.

Page DL, Schuyler PA, Dupont WD, et al. Atypical lobular hyperplasia as a unilateral predictor of breast cancer risk: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2003;361:125–129.

Rosen PP, Senie R, Schottenfeld D, et al. Noninvasive breast carcinoma: frequency of unsuspected invasion and implications for treatment. Ann Surg 1979;189:377–382.

Wheeler JE, Enterline HT, Roseman JM, et al. Lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast. Long-term followup. Cancer 1974;34:554–563.

Andersen JA . Lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast. An approach to rational treatment. Cancer 1977;39:2597–2602.

Rosen PP, Kosloff C, Lieberman PH, et al. Lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast. Detailed analysis of 99 patients with average follow-up of 24 years. Am J Surg Pathol 1978;2:225–251.

Anderson BO, Calhoun KE, Rosen EL . Evolving concepts in the management of lobular neoplasia. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2006;4:511–522.

Middleton LP, Grant S, Stephens T, et al. Lobular carcinoma in situ diagnosed by core needle biopsy: when should it be excised? Mod Pathol 2003;16:120–129.

Crisi GM, Mandavilli S, Cronin E, et al. Invasive mammary carcinoma after immediate and short-term follow-up for lobular neoplasia on core biopsy. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27:325–333.

Sapino A, Frigerio A, Peterse JL, et al. Mammographically detected in situ lobular carcinomas of the breast. Virchows Arch 2000;436:421–430.

Georgian-Smith D, Lawton TJ . Calcifications of lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast: radiologic-pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001;176:1255–1259.

Li CI, Anderson BO, Daling JR, et al. Changing incidence of lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2002;75:259–268.

Page DL, Dupont WD, Rogers LW . Ductal involvement by cells of atypical lobular hyperplasia in the breast: a long-term follow-up study of cancer risk. Hum Pathol 1988;19:201–207.

Rosen PP, Braun Jr DW, Lyngholm B, et al. Lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast: preliminary results of treatment by ipsilateral mastectomy and contralateral breast biopsy. Cancer 1981;47:813–819.

Fisher ER, Land SR, Fisher B, et al. Pathologic findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project: twelve-year observations concerning lobular carcinoma in situ. Cancer 2004;100:238–244.

Marshall LM, Hunter DJ, Connolly JL, et al. Risk of breast cancer associated with atypical hyperplasia of lobular and ductal types. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1997;6:297–301.

McLaren BK, Schuyler PA, Sanders ME, et al. Excellent survival, cancer type, and Nottingham grade after atypical lobular hyperplasia on initial breast biopsy. Cancer 2006;107:1227–1233.

Page DL, Kidd Jr TE, Dupont WD, et al. Lobular neoplasia of the breast: higher risk for subsequent invasive cancer predicted by more extensive disease. Hum Pathol 1991;22:1232–1239.

Eusebi V, Magalhaes F, Azzopardi JG . Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma of the breast: an aggressive tumor showing apocrine differentiation. Hum Pathol 1992;23:655–662.

Bentz JS, Yassa N, Clayton F . Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma of the breast: clinicopathologic features of 12 cases. Mod Pathol 1998;11:814–822.

Frost AR, Tsangaris NT, Silverberg SG . Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in situ. In: Silverberg SG (ed.). Pathology Case Reviews, Vol. 1. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, 1996;27–31.

Middleton LP, Palacios DM, Bryant BR, et al. Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma: morphology, immunohistochemistry, and molecular analysis. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:1650–1656.

Sneige N, Wang J, Baker BA, et al. Clinical, histopathologic, and biologic features of pleomorphic lobular (ductal-lobular) carcinoma in situ of the breast: a report of 24 cases. Mod Pathol 2002;15:1044–1050.

Fadare O, Dadmanesh F, varado-Cabrero I, et al. Lobular intraepithelial neoplasia [lobular carcinoma in situ] with comedo-type necrosis: a clinicopathologic study of 18 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2006;30:1445–1453.

Fisher ER, Costantino J, Fisher B, et al. Pathologic findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project (NSABP) Protocol B-17. Five-year observations concerning lobular carcinoma in situ. Cancer 1996;78:1403–1416.

Rosen PP . Rosen's Breast Pathology 2nd edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, 2001.

Jacobs TW, Pliss N, Kouria G, et al. Carcinomas in situ of the breast with indeterminate features: role of E-cadherin staining in categorization. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:229–236.

de Leeuw WJ, Berx G, Vos CB, et al. Simultaneous loss of E-cadherin and catenins in invasive lobular breast cancer and lobular carcinoma in situ. J Pathol 1997;183:404–411.

Acs G, Lawton TJ, Rebbeck TR, et al. Differential expression of E-cadherin in lobular and ductal neoplasms of the breast and its biologic and diagnostic implications. Am J Clin Pathol 2001;115:85–98.

Maluf HM, Swanson PE, Koerner FC . Solid low-grade in situ carcinoma of the breast: role of associated lesions and E-cadherin in differential diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:237–244.

Reis-Filho JS, Simpson PT, Jones C, et al. Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma of the breast: role of comprehensive molecular pathology in characterization of an entity. J Pathol 2005;207:1–13.

Moinfar F, Man YG, Lininger RA, et al. Use of keratin 35betaE12 as an adjunct in the diagnosis of mammary intraepithelial neoplasia-ductal type—benign and malignant intraductal proliferations. Am J Surg Pathol 1999;23:1048–1058.

Bratthauer GL, Miettinen M, Tavassoli FA . Cytokeratin immunoreactivity in lobular intraepithelial neoplasia. J Histochem Cytochem 2003;51:1527–1531.

Goldstein NS, Bassi D, Watts JC, et al. E-cadherin reactivity of 95 noninvasive ductal and lobular lesions of the breast. Implications for the interpretation of problematic lesions. Am J Clin Pathol 2001;115:534–542.

Da SL, Parry S, Reid L, et al. Aberrant expression of E-cadherin in lobular carcinomas of the breast. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:773–783.

Dabbs DJ, Kaplai M, Chivukula M, et al. The spectrum of morphomolecular abnormalities of the E-cadherin/catenin complex in pleomorphic lobular carcinoma of the breast. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2007;15:260–266.

Dabbs DJ, Bhargava R, Chivukula M . Lobular versus ductal breast neoplasms: the diagnostic utility of p120 catenin. Am J Surg Pathol 2007;31:427–437.

Lakhani SR, Collins N, Sloane JP, et al. Loss of heterozygosity in lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast. Clin Mol Pathol 1995;48:M74–M78.

Sarrio D, Moreno-Bueno G, Hardisson D, et al. Epigenetic and genetic alterations of APC and CDH1 genes in lobular breast cancer: relationships with abnormal E-cadherin and catenin expression and microsatellite instability. Int J Cancer 2003;106:208–215.

Droufakou S, Deshmane V, Roylance R, et al. Multiple ways of silencing E-cadherin gene expression in lobular carcinoma of the breast. Int J Cancer 2001;92:404–408.

Vos CB, Cleton-Jansen AM, Berx G, et al. E-cadherin inactivation in lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast: an early event in tumorigenesis. Br J Cancer 1997;76:1131–1133.

Berx G, Cleton-Jansen AM, Strumane K, et al. E-cadherin is inactivated in a majority of invasive human lobular breast cancers by truncation mutations throughout its extracellular domain. Oncogene 1996;13:1919–1925.

Mastracci TL, Tjan S, Bane AL, et al. E-cadherin alterations in atypical lobular hyperplasia and lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast. Mod Pathol 2005;18:741–751.

Lu YJ, Osin P, Lakhani SR, et al. Comparative genomic hybridization analysis of lobular carcinoma in situ and atypical lobular hyperplasia and potential roles for gains and losses of genetic material in breast neoplasia. Cancer Res 1998;58:4721–4727.

Mastracci TL, Boulos FI, Andrulis IL, et al. Genomics and premalignant breast lesions: clues to the development and progression of lobular breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2007;9:215.

Hwang ES, Nyante SJ, Yi CY, et al. Clonality of lobular carcinoma in situ and synchronous invasive lobular carcinoma. Cancer 2004;100:2562–2572.

Palacios J, Sarrio D, Garcia-Macias MC, et al. Frequent E-cadherin gene inactivation by loss of heterozygosity in pleomorphic lobular carcinoma of the breast. Mod Pathol 2003;16:674–678.

Raju U . Molecular classification of breast carcinoma in situ. Current Genomics 2006;8:523–532.

Simpson PT, Reis-Filho JS, Gale T, et al. Molecular evolution of breast cancer. J Pathol 2005;205:248–254.

Arpino G, Allred DC, Mohsin SK, et al. Lobular neoplasia on core-needle biopsy—clinical significance. Cancer 2004;101:242–250.

Bauer VP, Ditkoff BA, Schnabel F, et al. The management of lobular neoplasia identified on percutaneous core breast biopsy [see comment]. Breast J 2003;9:4–9.

Berg WA, Mrose HE, Ioffe OB . Atypical lobular hyperplasia or lobular carcinoma in situ at core-needle breast biopsy. Radiology 2001;218:503–509.

Bonnett M, Wallis T, Rossmann M, et al. Histopathologic analysis of atypical lesions in image-guided core breast biopsies. Mod Pathol 2003;16:154–160.

Cangiarella J, Waisman J, Symmans WF, et al. Mammotome core biopsy for mammary microcalcification: analysis of 160 biopsies from 142 women with surgical and radiologic follow-up. Cancer 2001;91:173–177.

Cassano E, Urban LA, Pizzamiglio M, et al. Ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted core breast biopsy: experience with 406 cases. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2007;102:103–110.

Diebold T, Hahn T, Solbach C, et al. Evaluation of the stereotactic 8G vacuum-assisted breast biopsy in the histologic evaluation of suspicious mammography findings (BI-RADS IV). Invest Radiol 2005;40:465–471.

Dillon MF, McDermott EW, Hill AD, et al. Predictive value of breast lesions of ‘uncertain malignant potential’ and ‘suspicious for malignancy’ determined by needle core biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol 2007;14:704–711.

Dmytrasz K, Tartter PI, Mizrachy H, et al. The significance of atypical lobular hyperplasia at percutaneous breast biopsy. Breast J 2003;9:10–12.

Elsheikh TM, Silverman JF . Follow-up surgical excision is indicated when breast core needle biopsies show atypical lobular hyperplasia or lobular carcinoma in situ: a correlative study of 33 patients with review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:534–543.

Esserman LE, Lamea L, Tanev S, et al. Should the extent of lobular neoplasia on core biopsy influence the decision for excision? Breast J 2007;13:55–61.

Fajardo LL, Pisano ED, Caudry DJ, et al. Stereotactic and sonographic large-core biopsy of nonpalpable breast lesions: results of the Radiologic Diagnostic Oncology Group V study. Acad Radiol 2004;11:293–308.

Dershaw DD . Does LCIS or ALH without other high-risk lesions diagnosed on core biopsy require surgical excision? Breast J 2003;9:1–3.

Foster MC, Helvie MA, Gregory NE, et al. Lobular carcinoma in situ or atypical lobular hyperplasia at core-needle biopsy: is excisional biopsy necessary? Radiology 2004;231:813–819.

Irfan K, Brem RF . Surgical and mammographic follow-up of papillary lesions and atypical lobular hyperplasia diagnosed with stereotactic vacuum-assisted biopsy. Breast J 2002;8:230–233.

Karabakhtsian RG, Johnson R, Sumkin J, et al. The clinical significance of lobular neoplasia on breast core biopsy. Am J Surg Pathol 2007;31:717–723.

Liberman L, Sama M, Susnik B, et al. Lobular carcinoma in situ at percutaneous breast biopsy: surgical biopsy findings. AJR 1999;173:291–299.

Mahoney MC, Robinson-Smith TM, Shaughnessy EA . Lobular neoplasia at 11-gauge vacuum-assisted stereotactic biopsy: correlation with surgical excisional biopsy and mammographic follow-up. AJR 2006;187:949–954.

Margenthaler JA, Duke D, Monsees BS, et al. Correlation between core biopsy and excisional biopsy in breast high-risk lesions. Am J Surg 2006;192:534–537.

O’Driscoll D, Britton P, Bobrow L, et al. Lobular carcinoma in situ on core biopsy-what is the clinical significance? Clin Radiol 2001;56:216–220.

Orel SG, Rosen M, Mies C, et al. MR imaging-guided 9-gauge vacuum-assisted core-needle breast biopsy: initial experience. Radiology 2006;238:54–61.

Philpotts LE, Shaheen NA, Jain KS, et al. Uncommon high-risk lesions of the breast diagnosed at stereotactic core-needle biopsy: clinical importance [see comment]. Radiology 2000;216:831–837.

Renshaw AA, Cartagena N, Derhagopian RP, et al. Lobular neoplasia in breast core needle biopsy specimens is not associated with an increased risk of ductal carcinoma in situ or invasive carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol 2002;117:797–799.

Sauer G, Deissler H, Strunz K, et al. Ultrasound-guided large-core needle biopsies of breast lesions: analysis of 962 cases to determine the number of samples for reliable tumour classification. Br J Cancer 2005;92:231–235.

Shin SJ, Rosen PP . Excisional biopsy should be performed if lobular carcinoma in situ is seen on needle core biopsy. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2002;126:697–701.

Yeh IT, Dimitrov D, Otto P, et al. Pathologic review of atypical hyperplasia identified by image-guided breast needle core biopsy. Correlation with excision specimen. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2003;127:49–54.

Menon S, Porter GJR, Evans AJ, et al. The significance of lobular neoplasia on needle core biopsy of the breast. Virchows Arch 2008;452:473–479.

Hwang H, Barke LD, Mendelson EB, et al. Atypical lobular hyperplasia and classic lobular carcinoma in situ in core biopsy specimens: routine excision is not necessary. Mod Pathol 2008;21:1208–1216.

Renshaw AA, Derhagopian RP, Martinez P, et al. Lobular neoplasia in breast core needle biopsy specimens is associated with a low risk of ductal carcinoma in situ or invasive carcinoma on subsequent excision. Am J Clin Pathol 2006;126:310–313.

Cohen MA . Cancer upgrades at excisional biopsy after diagnosis of atypical lobular hyperplasia or lobular carcinoma in situ at core-needle biopsy: some reasons why. Radiology 2004;231:617–621.

Bowman K, Munoz A, Mahvi DM, et al. Lobular neoplasia diagnosed at core biopsy does not mandate surgical excision. J Surg Res 2007;142:275–280.

Jacobs TW, Connolly JL, Schnitt SJ . Nonmalignant lesions in breast core needle biopsies: to excise or not to excise? Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:1095–1110.

Nagi CS, O’Donnell JE, Tismenetsky M, et al. Lobular neoplasia on core needle biopsy does not require excision. Cancer 2008;112:2152–2158.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Disclosure/conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

O'Malley, F. Lobular neoplasia: morphology, biological potential and management in core biopsies. Mod Pathol 23 (Suppl 2), S14–S25 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2010.35

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2010.35

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast: a single institution experience with clinical follow-up and centralized pathology review

Breast Cancer Research and Treatment (2017)

-

High-Risk Lesions at Minimally Invasive Breast Biopsy: Now What?

Current Radiology Reports (2017)

-

Lobular neoplasia detected in MRI-guided core biopsy carries a high risk for upgrade: a study of 63 cases from four different institutions

Modern Pathology (2016)

-

Underestimation rate of lobular intraepithelial neoplasia in vacuum-assisted breast biopsy

European Radiology (2014)