Abstract

The role of sentinel lymph node biopsy in microinvasive breast carcinoma is unclear. We examined the incidence of lymph node metastasis in patients with microinvasive carcinoma who underwent surgery at our institution. Retrospective review of our pathology database was performed (1994–2012). Of 7000 patients surgically treated for invasive breast carcinoma, 99 (1%) were classified as microinvasive carcinoma. Axillary staging was performed in 81 patients (64, sentinel lymph node biopsy; 17, axillary lymph node excision). Seven cases (9%) showed isolated tumor/epithelial cells in sentinel nodes. Three of these seven cases showed reactive changes in lymph nodes, papillary lesions in the breast with or without displaced epithelial cells within biopsy site tract, or immunohistochemical (estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2) discordance between the primary tumor in the breast and epithelial cells in the lymph node, consistent with iatrogenically transported epithelial cells rather than true metastasis. The remaining four cases included two cases, each with a single cytokeratin-positive cell in the subcapsular sinus detected by immunohistochemistry only, and two cases with isolated tumor cells singly and in small clusters (<20 cells per cross-section) by hematoxylin and eosin and immunohistochemistry. The exact nature of cytokeratin-positive cells in the former two cases could not be determined and might still have represented iatrogenically displaced cells. In the final analysis, only two cases (3%) had isolated tumor cells. Three of these four cases had additional axillary lymph nodes excised, which were all negative for tumor cells. At a median follow-up of 37 months (range 6–199 months), none of these patients had axillary recurrences. Our results show very low incidence of sentinel lymph node involvement (3%), only as isolated tumor cells, in microinvasive carcinoma patients. None of our cases showed micrometastases or macrometastasis. We recommend reassessment of the routine practice of sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with microinvasive carcinoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Microinvasive carcinoma is a rare subset of breast carcinoma comprising 0.7–2.4% of all patients with breast cancer1 and is defined as one or more areas of focal invasion, none larger than 1 mm in size.2 Microinvasive carcinoma is almost always observed in the background of duct carcinoma in situ, but rarely can be present in isolation. Owing to its low incidence, the prognosis of microinvasive carcinoma is not well established, but is believed to be intermediate between duct carcinoma in situ and invasive breast carcinomas.3, 4 The reported incidence of axillary lymph node metastasis in microinvasive carcinoma ranges between 0 and 25%.4, 5 Given the high incidence of axillary lymph node metastasis in some reports, sentinel lymph node biopsy is routinely performed in patients with microinvasive carcinoma. In addition, many patients undergo second surgical procedure for sentinel lymph node biopsy when a diagnosis of microinvasive carcinoma is rendered on definitive surgery as an upgrade to duct carcinoma in situ diagnosed on core biopsy.

The aim of the present study was to determine the incidence of axillary lymph node metastasis in patients diagnosed with microinvasive carcinoma and to ascertain whether routine use of sentinel lymph node biopsy for axillary staging is justified in patients with microinvasive carcinoma.

Materials and methods

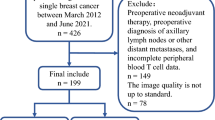

Approval from the Institutional Review Board of The Mount Sinai Hospital was obtained for this study. The surgical pathology database of the Department of Pathology at The Mount Sinai Hospital was searched between the years 1994 and 2012 using the keywords ‘microinvasive carcinoma’ and ‘breast.’ Only cases that underwent surgery at our institution were included in this study. Microinvasive carcinoma was defined using the current AJCC 7th edition definition of one or more foci of invasion, none being larger than 1 mm.

Each patient’s clinical and pathologic data, including age, gender, number of invasive foci, differentiation, associated duct carcinoma in situ, comedo necrosis, biomarker status, sentinel/axillary lymph node status, and follow-up, were recorded.

At our institution, each sentinel lymph node was sectioned at 2-mm intervals along the long axis and is entirely submitted for permanent histologic sections. Five additional levels and two immunohistochemical stains for cytokeratins (AE1/AE3 and CAM5.2) are evaluated on each sentinel lymph node to detect low volume metastases. Intraoperative evaluation of sentinel lymph nodes is performed only by cytology touch preparations. Lymph nodes are not submitted for frozen sections to avoid loss of lymph node material during frozen tissue processing.

Lymph node metastases are classified by the current AJCC criteria as macrometastases (metastases >2 mm in size), micrometastases (metastases 0.2–2 mm or >200 cells per cross-section), or isolated tumor cells (metastases <0.2 mm or <200 cells per cross-section).

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) slides were re-examined and evaluated in cases with lymph nodes positive for tumor/epithelial cells. Appropriate immunohistochemical stains including estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2 was performed on the nodes positive for tumor/epithelial cells whenever possible. The histomorphologic and immunohistochemical features of the primary breast carcinoma and the isolated tumor/epithelial cells in the lymph nodes were compared. Reactive changes such as hemosiderin laden macrophages, damaged erythrocytes, foreign body giant cells, if present in the lymph nodes, were recorded. Special attention was taken to identify any associated papillary lesions and/or displaced epithelial fragments within the biopsy tract of the lumpectomy or mastectomy specimens.

Results

Of the 7000 patients operated for invasive breast carcinoma between 1994 and 2012 at our institution, 99 (1%) were classified as microinvasive carcinoma. A summary of clinical and pathologic features is provided in Table 1.

The median age of patients was 56 years (range, 31–83 years). The diagnosis of microinvasive carcinoma was rendered on diagnostic core biopsy in 37 patients, lumpectomy in 43 patients, and mastectomy in 19 patients. The clinical presentation was unknown in four (4%) patients. Clinically, the majority of patients presented with calcifications (68, 72%), followed by mass (16, 17%), mass with calcifications (2, 2%), palpable mass (2, 2%), asymmetry (2, 2%), enhancement (2, 2%), nipple discharge (1, 1%), and Paget’s disease (1, 1%). One (1%) patient was asymptomatic and was diagnosed with microinvasive carcinoma on prophylactic mastectomy. Twenty-eight (28%) patients underwent total mastectomy and 71 (72%) underwent breast-conserving surgery. Eighty-one (82%) patients had axillary staging with or without sentinel lymph node biopsy procedure. Sixty-four (79%) of these 81 patients had sentinel lymph node biopsy with an average of two sentinel lymph nodes excised (range, 1–13). The remaining 17 (21%) patients underwent axillary lymph node dissection at the time of first surgery. The latter group of patients had surgery in the early years of study when sentinel lymph node biopsy was not yet prevalent. Thirteen patients (13%) underwent a second surgical procedure for sentinel lymph node/axillary lymph node staging.

Ninety-three (94%) tumors were of ductal differentiation and 6 (6%) of lobular differentiation. Histological grade was not reported in 21 (21%) patients. Thirteen (17%) were well-differentiated, 31 (40%) were moderately differentiated and 34 (44%) were poorly differentiated. Duct carcinoma in situ was present in association with microinvasive carcinoma in 97 (98%) patients. The remaining two (2%) patients had isolated microinvasive carcinoma in the absence of an in situ carcinoma. Duct carcinoma in situ was high grade in 65 (71%), intermediate grade in 25 (27%) and low grade in 4 (4%). Duct carcinoma in situ grade was unknown in 5 (5%) patients. Sixty-five (67%) patients had duct carcinoma in situ with comedo necrosis. Microinvasive carcinoma was multifocal in 19 (19%) patients. Only one (1%) patient had evidence of lymphatic tumor emboli.

Hormone receptor status was available for 64 patients. Forty-one (64%) patients were positive for ER and 36 (56%) for PR. HER2 status was known in 51 patients, including 21 (41%) positive, 27 (53%) negative, and 3 (6%) equivocal cases.

Of the 81 patients, who underwent axillary staging, 7 (9%) showed isolated tumor/epithelial cells in sentinel lymph node. The clinical and pathologic features of these seven patients are summarized in Table 2. These patients (mean age 49 years) presented with palpable breast mass (1), mass (1), mass with calcifications (1), or calcifications (4). The microinvasive component showed well (1), moderate (4), and poor (2) differentiation. Two of the seven patients (29%) had multifocal microinvasion. All seven cases showed either intermediate (4) or high-grade (3) duct carcinoma in situ, of which three had comedo necrosis.

Three of these seven cases (4%) also showed reactive changes in lymph node, such as multinucleated giant cells and hemosiderin-laden macrophages adjacent to the isolated tumor/epithelial cells (Figure 1f). Review of sections from the breast demonstrated the presence of intraductal papillomas (intraductal papilloma was benign in one case and involved by duct carcinoma in situ in two cases) with or without displaced epithelial cells within granulation tissue of biopsy site (Figures 1a–c). Furthermore, the immunohistochemical profile of the primary and tumor/epithelial cells in lymph nodes was different from that of the primary breast microinvasive carcinoma in these three cases (Figures 1d and e). In view of the above histologic features and discordant immunohistochemistry staining patterns, these three cases were classified as being consistent with iatrogenically displaced epithelial cells rather than true metastasis. It is noteworthy that these three patients underwent a sentinel lymph node biopsy procedure as an additional surgery after their primary surgical excision.

Patient 2: iatrogenically displaced epithelial cells. Microinvasive carcinoma (arrow) in a background of duct carcinoma in situ involving an intraductal papilloma (a and b); epithelial displacement within the biopsy site granulation tissue (c); microinvasive carcinoma positive for estrogen receptor (ER) (d) and progesterone receptor (PR) (e); cytokeratin-positive (CK+) (CAM5.2) cluster of epithelial cells in sentinel lymph node is nuclear stain negative for ER (g) and PR (h); hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain verifies the cell cluster in sentinel lymph node (f). Note the reactive changes associated with epithelial cells in the lymph node (f).

Two of the seven cases (3%) showed a single cytokeratin-positive cell in the subcapsular sinus detected by immunohistochemistry only (Figures 2a–c). Sections from the breasts did not reveal any papillary lesion or displaced epithelial fragments within the biopsy tract. Immunohistochemistry for ER, PR, and HER2 was not technically feasible in these cases. Therefore, the exact nature of single cytokeratin-positive cells in these two cases could not be determined and they could still represent iatrogenically displaced cells.

Patient 5: exact nature undetermined, and may still represent iatrogenically displaced cell. Microinvasive carcinoma (arrow) in the background of duct carcinoma in situ (a); microinvasive carcinoma at higher magnification (b, × 200); sentinel lymph node with single cytokeratin–positive (CK+) (CAM5.2) cell in the subcapsular sinus (c).

The remaining two cases (3%) showed isolated tumor cells singly and in small clusters (<20 cells per cross-section), detected by H&E stain and immunohistochemistry (Figures 3d and h). One of the cases demonstrated a focus of reactive changes in the lymph node separate from the tumor cell clusters (Figure 3i). The ER, PR, and HER2 staining pattern of the lymph nodal cells was similar to that of the respective primary microinvasive carcinoma (Figures 3e–g). In one of these two cases, microinvasive carcinoma was diagnosed on core biopsy and the patient underwent mastectomy with sentinel lymph node biopsy owing to widespread extent of duct carcinoma in situ. Initial histologic sections from the breast in this case confirmed widespread duct carcinoma in situ, involving intraductal papillomas. In addition, a few displaced epithelial fragments within the biopsy tract and tumor emboli within two lymphatic spaces were also noted (Figures 3a–c). In view of the presence of lymphatic tumor emboli, additional extensive sampling to rule out the possibility of an occult invasive carcinoma was done; however, no additional focus of invasion was identified. The other case did not reveal any papillary lesion or displaced epithelial fragments. Hence, these were the only two definitive cases (3%) with minimal tumor volume (isolated tumor cells) in the axilla.

Patient 4 with minimal tumor volume in sentinel lymph node (isolated tumor cell; <0.2 mm and <200 cells). Section from mastectomy shows high-grade duct carcinoma in situ involving an intraductal papilloma (a); displaced tumor cell clusters within a biopsy site tract (b) and lymphatics (c); sentinel lymph node with subcapsular cytokeratin–positive (CK+) (CAM5.2) cluster of tumor cells (d) positive for estrogen receptor (ER) (e) and progesterone receptor (PR) (f), and negative for HER2 protein (g); cluster of cells was verified by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (h); another focus of reactive changes in the same lymph node (i). Note:This patient was diagnosed with microinvasive carcinoma on core biopsy (positive for ER and PR, but negative for HER2 protein). Hence, ER, PR and HER2 staining pattern of epithelial cells in the sentinel lymph node is similar to that of primary in breast.

Four of these seven cases had additional axillary lymph nodes excised (range, 1–5), all of which were negative for tumor cells. None of these seven patients received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Follow-up data were available in 68 (69%) patients with a median follow-up of 37 months (range, 6–199 months). Of these patients, the seven with isolated tumor/epithelial cells had follow-up data available for six patients (median, 28 months; range, 14–126 months). None of the 68 patients developed axillary recurrences. However, three patients developed ipsilateral local recurrences in the breast (duct carcinoma in situ, 2; and invasive breast cancer, 1). All three recurrences occurred in patients with negative sentinel lymph nodes. These three cases had negative surgical resection margins.

Discussion

The clinical management of the axilla in microinvasive carcinoma patients is controversial. There are only a limited number of publications in the literature addressing this issue (Table 3). Results of these studies have varied widely with reported incidence of axillary lymph node involvement as low as 0% to as high as 25%.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39 Authors reporting a high incidence of positive sentinel lymph nodes argue in favor of sentinel lymph node biopsy in all patients with microinvasive carcinoma,9, 19, 28, 30, 31 whereas authors reporting the low incidence of positive sentinel lymph nodes have questioned whether sentinel lymph node biopsy should be performed in all such patients.32, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38

The wide variation in reported incidence can be explained in part by the diversity in the histopathologic definition of microinvasive carcinoma used in various reports. In 1982, Lagios et al,40 while describing series of cases of duct carcinoma in situ, coined the term ‘microinvasion’ for cases showing invasion <1 mm. In 1986, Schuh et al5 defined microinvasive carcinoma as ‘duct carcinoma in situ with the presence of early stromal invasion.’ In 1990, Wong et al7 defined microinvasive carcinoma as ‘intraductal carcinoma with only a microscopic focus of malignant cells invading beyond the basement membrane of the duct.’ In 1991, Rosner et al8 defined microinvasive carcinoma as ‘duct carcinoma in situ with limited microscopic stromal invasion below the basement membrane in one or several ducts but not invading more than 10% of the surface of the histologic sections examined.’ Silverstein et al10 defined microinvasion as ‘1 or 2 min microscopic foci of possible invasion no more than 1 mm in maximum diameter.’ Later, the 5th edition of the AJCC staging manual defined microinvasive carcinoma as extension of carcinoma cells beyond basement membrane with no single focus >1 mm, whereas Silver and Tavassoli11 defined it as a single focus of invasive carcinoma ⩽2 mm or up to three foci of invasion, each ⩽1 mm in greatest dimension. The current definition of microinvasive carcinoma per the 7th edition of the AJCC manual remains unchanged from its prior definition.2 A second reason for the wide range is the lack of a universal protocol for processing sentinel lymph nodes. The grossing methods of sentinel lymph nodes, the number of additional levels evaluated (if any), and the use of immunohistochemistry for cytokeratins varies from institution to institution, certainly influencing the rate of detection of metastases. A third possible reason for a high incidence is that iatrogenic transport of tumor/epithelial cells to lymph nodes may be misinterpreted as true metastasis.41

Our study cohort shows a very low incidence (2.5%) of positive sentinel lymph nodes and only in the form of minimal tumor volume (isolated tumor cells). None of our cases showed micro- or macrometastases, or involvement of additional non-sentinel axillary lymph nodes. Some of the larger studies in recent years have also concluded that involvement of sentinel lymph nodes in microinvasive carcinoma is primarily in the form of isolated tumor cells and micrometastases, and additional non-sentinel axillary lymph nodes are positive only when the sentinel lymph node harbors a macrometastases.4, 35, 36, 37, 38 The study by Ko et al,37 the largest so far, reported axillary lymph node involvement in 22 of 293 cases (7.5%), with 18 of the 22 cases (81.8%) harboring only isolated tumor cells or micrometastases. Lyons et al,4 in their study of 112 microinvasive carcinoma cases, identified 14 cases (12%) with positive sentinel lymph nodes, including 6 (42.8%) with isolated tumor cells, 5 (35.7%) with micrometastases, and 3 (21.4%) with macrometastases. Two of the three patients with macrometastases had additional positive axillary nodes upon completion axillary lymph node dissection, whereas none of the isolated tumor cells or micrometastasis cases that underwent completion axillary lymph node dissection had additional positive nodes. Kapoor et al38 also reported a low incidence of macrometastases of 1 out of 45 cases (2.2%).

The clinical and prognostic significance of minimal tumor burden in the axilla of breast cancer patients is uncertain. As the majority of microinvasive carcinoma patients (more than 90%) harbor only isolated tumor cells and micrometastases, one might reasonably conclude that sentinel lymph node biopsy and its rigorous pathologic evaluation is an unnecessary exercise in a case of microinvasive carcinoma. Further, these patients may be unreasonably subjected to rare, but potential complications of sentinel lymph node biopsy, such as infection, pain, limited arm mobility, or lymphedema. Results of two recent prospective trials ACOSOG Z0010 and NSABP Protocol B-32 indicate that positive nodes detected by immunohistochemistry only, as well as micrometastases, do not affect 5-year overall survival in early invasive breast cancer.42, 43 In both trials, 5-year overall survival for patients with immunohistochemistry detected isolated tumor cells or micrometastases approached 95% and was not significantly different from the patients without any sentinel lymph node disease. Another study by Murphy et al44 on 322 patients of duct carcinoma in situ/microinvasive carcinoma showed a very low incidence of sentinel lymph node involvement (3.7%) in microinvasive carcinoma patients and did not find a higher risk of local or distant recurrence in patients with axillary disease, questioning the need for surgical exploration of the axilla. Similarly, Parikh et al36 in their comparative study of duct carcinoma in situ and microinvasive carcinoma (321 duct carcinoma in situ patients versus 72 microinvasive carcinoma patients) found a very low incidence of nodal metastases (1 of 72, 2.1%) in microinvasive carcinoma patients, and the axillary nodal metastases was not an independent predictor of local relapse-free survival, distant relapse-free survival, or overall survival. Our follow-up data (range, 6–199 months) is consistent with the above studies. No axillary recurrence was noted and the three cases with ipsilateral local in-breast recurrence did not have positive lymph nodes.

Some authors may argue that sentinel lymph node biopsy should nevertheless be offered in all microinvasive carcinoma patients to identify patients with sentinel lymph node macrometastases, that is, those who may benefit from additional axillary surgery or adjuvant treatment. This argument is valid to some extent because in current practice, treatment decisions regarding adjuvant chemotherapy in microinvasive carcinoma patient relies primarily on the axillary lymph node status. In the study by Kapoor et al,38 seven of nine patients with lymph node metastases (77.8%) received adjuvant chemotherapy, whereas no patients without lymph node metastasis received chemotherapy. Similarly, in the study by Lyons et al4 from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 8 of 14 microinvasive carcinoma patients (57.1%) with nodal metastases received chemotherapy as compared with only 4 of 98 (4%) patients without lymph nodal disease. In addition, at present there is insufficient data regarding clinical or pathologic features directly correlating with sentinel lymph node metastases. A few studies have attempted to correlate the clinical and histologic features, such as young age,30, 32 palpable mass,19 multifocal disease,17 poor differentiation,32 comedo duct carcinoma in situ,18 number of ducts involved by duct carcinoma in situ,18 lymphovascular invasion,37 and ER status,37, 38 with positive sentinel lymph nodes; however, the results have been conflicting. Our study did not show any case of sentinel lymph node micro- and macrometastases, and therefore analysis on correlating factors was not carried out. None of our patients received adjuvant therapy based on the sentinel lymph node results.

Our study highlights that isolated tumor cells in lymph nodes should be interpreted with caution as they may represent iatrogenically displaced tumor/epithelial cells, particularly in the setting of a papillary lesion in the breast. At our institution, we routinely perform detailed histologic and immunohistochemical work-up of all duct carcinoma in situ and microinvasive carcinoma cases showing isolated tumor/epithelial cells in lymph nodes. Lymph nodes are rigorously screened for the presence of reactive changes. Although reactive changes in the lymph node are suggestive of iatrogenic displacement, they are not exclusively diagnostic and require additional work-up. ER, PR, and HER2 staining is carried out on lymph nodes and the staining pattern of the epithelial cells is compared with that of the primary breast carcinoma. Sections from the breast are evaluated for the presence of any associated papillary lesions that are known to be friable and more prone to iatrogenic displacement during needle biopsies or breast massage before sentinel lymph node biopsy procedure.41 Particular attention is placed on identifying displaced epithelial fragments entrapped within the biopsy site tracts. Using this strategy, we are usually able to distinguish the true metastases from false-positive sentinel lymph nodes. Three of the seven cases (43%) were unquestionably proven to have iatrogenically displaced tumor/epithelial cells.

To conclude, our study is one of the larger studies of microinvasive carcinoma patients. Our results demonstrate a very low incidence of sentinel lymph node metastases in microinvasive carcinoma patients, exclusively limited to isolated tumor cells. This study highlights that many of the so-called ‘positive’ sentinel lymph nodes are falsely positive secondary to iatrogenic transport of displaced epithelial cells. Careful pathologic evaluation of sentinel lymph nodes and the surgical breast specimen is required to avoid false positives and subsequent unwarranted axillary surgery or adjuvant treatment. In the context of our results and data generated by ACOSOG Z0010 and NSABP Protocol B32, we recommend reassessment of the routine surgical practice of sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with microinvasive carcinoma. Alternative procedures to sentinel lymph node biopsy such as preoperative ultrasound and ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of axilla should be explored.

References

Hoda SA, Chiu A, Prasad ML et al. Are microinvasion and micrometastasis in breast cancer mountains or mole hills? Am J Surg 2000;180:305–308.

American Joint Committee on Cancer. AJCC cancer staging manual In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton C et al (eds). Breast 7th edn. Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010, Part VIII p 417 and 160.

Bianchi S, Vezzosi V . Microinvasive carcinoma of the breast. Pathol Oncol Res 2008;14:105–111.

Lyons JM, Stempel M, Van Zee KJ et al. Axillary node staging for microinvasive breast cancer: is it justified? Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:3416–3421.

Schuh ME, Nemoto T, Penetrante RB et al. Intraductal carcinoma. Analysis of presentation, pathologic findings, and outcome of disease. Arch Surg 1986;121:1303–1307.

Kinne DW, Petrek JA, Osborne MP et al. Breast carcinoma in situ. Arch Surg 1989;124:33–36.

Wong JH, Kopald KH, Morton DL . The impact of microinvasion on axillary node metastases and survival in patients with intraductal breast cancer. Arch Surg 1990;125:1298–1301.

Rosner D, Lane WW, Penetrante R . Ductal carcinoma in situ with microinvasion. A curable entity using surgery alone without need for adjuvant therapy. Cancer 1991;67:1498–1503.

Solin LJ, Fowble BL, Yeh IT et al. Microinvasive ductal carcinoma of the breast treated with breast-conserving surgery and definitive irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1992;23:961–968.

Silverstein MJ . Ductal carcinoma in situ with microinvasion In: Silverstein MJ, (ed) Ductal Carcinoma In Situ of Breast. Williams and Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1997, pp 557–562.

Silver SA, Tavassoli FA . Mammary ductal carcinoma in situ with microinvasion. Cancer 1998;82:2382–2390.

Zavotsky J, Hansen N, Brennan MB et al. Lymph node metastasis from ductal carcinoma in situ with microinvasion. Cancer 1999;85:2439–2443.

Klauber-DeMore N, Tan LK, Liberman L et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy: is it indicated in patients with high-risk ductal carcinoma-in-situ and ductal carcinoma-in-situ with microinvasion? Ann Surg Oncol 2000;7:636–642.

Padmore RF, Fowble B, Hoffman J et al. Microinvasive breast carcinoma: clinicopathologic analysis of a single institution experience. Cancer 2000;88:1403–1409.

Prasad ML, Osborne MP, Giri DD et al. Microinvasive carcinoma (T1mic) of the breast: clinicopathologic profile of 21 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:422–428.

Cox CE, Nguyen K, Gray RJ et al. Importance of lymphatic mapping in ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS): Why map DCIS? Am Surg 2001;67:513–521.

De Mascarel I, MacGrogan G, Mathoulin-Pelissier S et al. Breast ductal carcinoma in situ with microinvasion. A definition supported by a long-term study of 1248 serially sectioned ductal carcinomas. Cancer 2002;94:2134–2142.

Wasserberg N, Morgenstern S, Schachter J et al. Risk factors for lymph node metastases in breast ductal carcinoma in situ with minimal invasive component. Arch Surg 2002;137:1249–1252.

Intra M, Zurrida S, Maffini F et al. Sentinel lymph node metastasis in microinvasive breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2003;10:1160–1165.

Yang M, Moriya T, Oguma M et al. Microinvasive ductal carcinoma (T1mic) of the breast. The clinicopathological profile and immunohistochemical features of 28 cases. Pathol Int 2003;53:422–428.

Camp R, Feezor R, Kasraeian A et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for ductal carcinoma in situ: an evolving approach at the University of Florida. Breast J 2005;11:394–397.

Wilkie C, White L, Dupont E et al. An update of sentinel lymph node mapping in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ. Am J Surg 2005;190:563–566.

Tunon-de-Lara C, Giard S, Buttarelli M et al. Sentinel node procedure is warranted in ductal carcinoma in situ with high risk of occult invasive carcinoma and microinvasive carcinoma treated by mastectomy. Breast J 2008;14:135–140.

Cavaliere A, Scheibel M, Bellezza G et al. Ductal carcinoma in situ with microinvasion: clinicopathologic study and biopathologic profile. Pathol Res Pract 2006;202:131–135.

Katz A, Gage I, Evans S et al. Sentinel lymph node positivity of patients with ductal carcinoma in situ or microinvasive breast cancer. Am J Surg 2006;191:761–766.

Broekhuizen LN, Wijsman JH, Peterse JL et al. The incidence and significance of micrometastases in lymph nodes of patients with ductal carcinoma in situ and T1a carcinoma of the breast. Eur J Surg Oncol 2006;32:502–506.

Leidenius M, Salmenkivi K, Von Smitten K et al. Tumor positive sentinel node findings in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ. J Surg Oncol 2006;94:380–384.

Zavagno G, Belardinelli V, Marconato R et al. Sentinel lymph node metastasis from mammary ductal carcinoma in situ with microinvasion. Breast 2007;16:146–151.

Gray RJ, Mulheron B, Pockaj BA et al. The optimal management of the axilla of patients with microinvasive breast cancer in the sentinel lymph node era. Am J Surg 2007;194:845–849.

Guth AA, Mercado C, Roses DF et al. Microinvasive breast cancer and the role of sentinel node biopsy: an institutional experience and review of the literature. Breast J 2008;14:335–339.

Sakr R, Barranger E, Antoine M et al. Ductal carcinoma in situ: value of sentinel lymph node biopsy. J Surg Oncol 2006;94:426–430.

Fortunato L, Santoni M, Drago S et alRome Breast Cancer Study Group. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in women with pT1a or ‘microinvasive’ breast cancer. Breast 2008;17:395–400.

Yi M, Krishnamurthy S, Kuerer HM et al. Role of primary tumor characteristics in predicting positive sentinel lymph nodes in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ or microinvasive breast cancer. Am J Surg 2008;196:81–87.

Vieira CC, Mercado CL, Cangiarella JF et al. Microinvasive ductal carcinoma in situ: clinical presentation, imaging features, pathologic findings, and outcome. Eur J Radiol 2010;73:102–107.

Pimiento JM, Lee MC, Esposito NN et al. Role of axillary staging in women diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ with microinvasion. J Oncol Pract 2011;7:309–313.

Parikh RR, Haffty BG, Lannin D et al. Ductal carcinoma in situ with microinvasion: prognostic implications, long-term outcomes, and role of axillary evaluation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010;82:7–13.

Ko BS, Lim WS, Kim HJ et al. Risk factor for axillary lymph node metastases in microinvasive breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:212–216.

Kapoor NS, Shamonki J, Sim MS et al. Impact of multifocality and lymph node metastasis on the prognosis and management of microinvasive breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:2576–2581.

Margalit DN, Sreedhara M, Chen Y-H et al. Microinvasive breast cancer: ER, PR, and HER-2/neu status and clinical outcomes after breast-conserving therapy or mastectomy. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:811–818.

Lagios MD, Wesdahl PR, Margolin FR et al. Duct carcinoma in situ. Relationship of extent of non invasive disease to the frequency of occult invasion, multicentricity, lymph node metastases, and short-term treatment failures. Cancer 1982;50:1309–1314.

Bleiweiss IJ, Nagi CS, Jaffer S . Axillary sentinel lymph nodes can be falsely positive due to iatrogenic displacement and transport of benign epithelial cells in patients with breast carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:2013–2018.

Giuliano AE, Hawes D, Ballman KV et al. Association of occult metastases in sentinel lymph nodes and bone marrow with survival among women with early-stage invasive breast cancer. JAMA 2011;306:385–393.

Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB et al. Sentinel-lymph-node resection compared with conventional axillary-lymph-node dissection in clinically node-negative patients with breast cancer: overall survival findings from the NSABP B-32 randomized phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:927–933.

Murphy CD, Jones JL, Javid SH et al. Do sentinel node micrometastases predict recurrence risk in ductal carcinoma in situ and ductal carcinoma in situ with microinvasion? Am J Surg 2008;196:566–568.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hanna, M., Jaffer, S., Bleiweiss, I. et al. Re-evaluating the role of sentinel lymph node biopsy in microinvasive breast carcinoma. Mod Pathol 27, 1489–1498 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2014.54

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2014.54

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Survival outcomes after breast-conserving surgery plus radiotherapy compared with mastectomy in breast ductal carcinoma in situ with microinvasion

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Clinical significance of epithelial–mesenchymal transition-related markers expression in the micrometastatic sentinel lymph node of NSCLC

Clinical and Translational Oncology (2020)

-

Sentinel and non-sentinel lymph node metastases in patients with microinvasive breast cancer: a nationwide study

Breast Cancer Research and Treatment (2019)

-

Consistency in recognizing microinvasion in breast carcinomas is improved by immunohistochemistry for myoepithelial markers

Virchows Archiv (2016)