Abstract

The current 2014 World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of mixed epithelial and mesenchymal tumours of the uterus includes categories of carcinosarcoma, adenosarcoma, adenofibroma, adenomyoma and atypical polypoid adenomyoma, the last two lesions being composed of an admixture of benign epithelial and mesenchymal elements with a prominent smooth muscle component. In this review, each of these categories of uterine neoplasm is covered with an emphasis on practical tips for the surgical pathologist and new developments. In particular, helpful clues in the distinction between carcinosarcoma and dedifferentiated endometrial carcinoma will be discussed. In addition, salient features to help distinguish between adenofibroma, adenosarcoma, embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma and other mesenchymal neoplasms in the differential diagnosis will be outlined. Finally, a discussion of adenomyoma and its main differential diagnostic considerations will be covered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Mixed epithelial and mesenchymal tumours of the uterus comprise a heterogenous group of neoplasms with categories of carcinosarcoma, adenosarcoma, adenofibroma, adenomyoma and atypical polypoid adenomyoma included in the current 2014 World Health Organization (WHO) Classification.1 In the prior WHO (2003), the category of carcinofibroma was included, but it has been removed in the present classification. Although very few cases have been reported in this category,2, 3 it is very difficult to prove that a morphologically benign stromal element in a carcinoma is an integral component of the neoplasm and not just a prominent reactive stromal response. Adenofibroma is also considered to be extremely rare, and is discussed in the differential diagnosis of adenosarcoma. In this review, the WHO categories of mixed epithelial and mesenchymal neoplasms with an emphasis on new developments and practical tips for the surgical pathologist will be covered.

Uterine carcinosarcoma

Clinical Features

Uterine carcinosarcoma (malignant Mixed Mullerian tumour) is an uncommon uterine tumour1 that accounts for less than 5% of uterine malignancies and typically occurs in elderly women. Associations include prior tamoxifen therapy, unopposed oestrogens and pelvic irradiation (10- to 20-year time interval).4, 5 Patients usually present with vaginal bleeding, but may have symptoms related to a pelvic mass or metastatic disease. Given that carcinosarcomas are, in essence, of epithelial derivation, they are staged as endometrial carcinomas; this is explicitly stated in the 2009 FIGO staging system for endometrial carcinomas.6

Pathological Features

Grossly, carcinosarcomas are often bulky, necrotic and haemorrhagic polypoid tumours, which fill the endometrial cavity and may protrude through the cervical os. There may be deep myometrial invasion and cervical involvement. Occasionally, they are confined to an endometrial polyp.7, 8

A histological diagnosis of carcinosarcoma depends on identifying high-grade malignant epithelial and mesenchymal components typically showing a sharp demarcation between both, although occasionally this demarcation may be blurred (Figure 1). The epithelial element may include serous, grade 3 endometrioid, clear cell and undifferentiated carcinoma in order of frequency. Admixtures may be seen and typing of the epithelial component may be difficult; in some cases, a hybrid morphology (with features of serous and endometrioid carcinoma) or a malignant squamous component is present (Figure 2), which may be a clue to the diagnosis. The mesenchymal component can be homologous or heterologous. The former is typically a high-grade sarcoma, NOS and eosinophilic hyaline globules are frequently noted. If heterologous elements are present, then rhabdomyoblasts or malignant cartilage is the most common. Osteosarcomatous and liposarcomatous differentiation may rarely occur (Figure 3). On occasion, carcinosarcomas are associated with a component of primitive neuroectodermal tumour (PNET); in such cases, markers such as neurofilament, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and synaptophysin may be useful in highlighting this component, which is more analogous to a central than a peripheral PNET without EWSR1 gene rearrangement.9 Occasional examples of a yolk sac tumour component and melanocytic differentiation have also been reported.10, 11

The relative proportions of epithelial and mesenchymal components vary widely; thus, extensive sampling in an undifferentiated sarcoma or pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma may reveal areas diagnostic of carcinosarcoma. Uncommonly, carcinosarcomas have a low-power growth pattern, which mimics an adenosarcoma (Figure 4); however, this is usually a focal finding, there is no stromal condensation, and the epithelium and the stroma are overtly malignant at high-power magnification.

In general, immunohistochemistry is of limited value in the diagnosis of carcinosarcoma as both malignant epithelial and mesenchymal components should be seen on morphological examination. However, immunohistochemistry may be useful in confirming the presence of a heterologous mesenchymal component which, as discussed later, is an adverse prognostic indicator in stage I neoplasms. For example, nuclear staining with myogenin and myoD1 helps to confirm the presence of rhabdomyoblastic differentiation.

Histogenesis

Although previously regarded as a subtype of uterine sarcoma, it is now well established that most carcinosarcomas are epithelial neoplasms that have undergone sarcomatous transformation, the epithelial component being the driving force; as such, they can be considered as akin to metaplastic or sarcomatoid carcinomas.12, 13 In fact, it would be more logical to include carcinosarcoma among the subtypes of uterine epithelial malignancies rather than within the mixed epithelial and mesenchymal neoplasms and certainly these should no longer be regarded as subtypes of uterine sarcoma. There are multiple lines of evidence for its epithelial origin, including a pattern of spread that is akin to that of other ‘high grade’ uterine carcinomas with rare exceptions and that morphologically the tumour within lymphovascular channels and metastatic sites usually comprises the epithelial, or much less commonly, a mixture of the epithelial and mesenchymal components rather than the sarcoma.14 There is also experimental evidence that most carcinosarcomas are monoclonal neoplasms rather than representing collision tumours.15, 16 p53 expression is usually concordant between the epithelial and mesenchymal components exhibiting a diffuse, null or wild-type pattern of expression, thus suggesting a common lineage for the two components.16 Occasionally, the sarcomatous component only manifests itself in the metastasis or recurrence of a high-grade endometrial carcinoma.

As the epithelial element is the ‘driving force’, carcinosarcoma can be viewed as exhibiting features of epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT).17, 18, 19 One study examined the expression of EMT-related genes in these neoplasms, and found that acquired markers of EMT were upregulated and attenuated markers of EMT were downregulated in carcinosarcomas.18

Behaviour

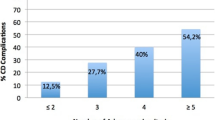

Carcinosarcomas are aggressive neoplasms, which often have extrauterine spread at presentation, and exhibit a behaviour more akin to that of other high-grade endometrial carcinomas than uterine sarcomas. Spread to pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes is common and sometimes there are distant metastases. Survival is largely dependent on stage, but overall 5-year survival is ~35%, being worse than that of other ‘high-grade’ endometrial carcinomas.15 There is some evidence that behaviour is worse when the epithelial component comprises non-endometrioid (serous, clear cell or undifferentiated) rather than endometrioid carcinoma. A relatively recent study has shown that in stage I uterine carcinosarcomas, the nature of the mesenchymal component is a powerful prognostic indicator; those tumours with heterologous elements having a significantly worse prognosis than those with only homologous mesenchymal component (3-year survival 45 vs 93% for heterologous and homologous neoplasms, respectively).20 Thus, it is recommended by the International Collaboration on Cancer Reporting (ICCR) that percentages of the epithelial and mesenchymal components as well the morphological subtypes within the epithelial and mesenchymal components be included on the pathology report.21

Differential Diagnosis

Tumours that may raise problems in the diagnosis of uterine carcinosarcoma include other types of ‘high-grade’ endometrial carcinoma as occasionally the mesenchymal component may be very limited. The WHO classification does not include any cutoff for the percentage of the mesenchymal component to qualify for a diagnosis of carcinosarcoma.1 It is possible that a minor malignant mesenchymal component in a neoplasm which otherwise comprises a ‘high grade’ carcinoma is of limited prognostic significance, but this remains to be ascertained. When considering a diagnosis of undifferentiated sarcoma or pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma within the uterus a carcinosarcoma (or much less frequently an adenosarcoma with sarcomatous overgrowth) should always be excluded; in such cases, extensive sampling in the hysterectomy specimen may reveal diagnostic areas of carcinosarcoma or adenosarcoma. Thus when dealing with a biopsy or curettage composed only of high-grade sarcoma, NOS or rhabdomyosarcoma, it is appropriate to render a descriptive diagnosis and state in a note that the differential includes a carcinosarcoma in which the carcinomatous component has not been sampled and an adenosarcoma with sarcomatous overgrowth in which the low-grade component has not been sampled, and less likely a pure sarcoma.

An unusual variant of endometrioid adenocarcinoma, which is often misdiagnosed as carcinosarcoma, is referred to as ‘corded and hyalinized endometrioid adenocarcinoma’. It is characterized by cords of epithelioid cells, spindle cells and a hyalinized stroma.22 Areas with a diffuse growth of fusiform cells may be present. Osteoid is sometimes noted, which can further result in consideration of a carcinosarcoma. These features, particularly when prominent, result in an appearance strikingly different from that of conventional endometrioid adenocarcinoma, often raising problems in differential diagnosis, especially with carcinosarcoma (since the corded and hyalinized and fusiform elements may be mistaken for a mesenchymal component). In corded and hyalinized endometrioid adenocarcinoma, there is typically a component of conventional low-grade endometrioid adenocarcinoma, with merging of the two components. In contrast, carcinosarcoma is characterized by high-grade carcinomatous and sarcomatous components, usually with a sharp demarcation between the two elements. Comparable tumours have been reported in the ovary; however, they more often show a spindled morphology.23

Another endometrial tumour that is commonly confused with carcinosarcoma is the combination of an undifferentiated endometrial carcinoma and a low-grade endometrioid adenocarcinoma (mixed endometrioid and undifferentiated carcinoma or dedifferentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma).24, 25, 26 Undifferentiated carcinoma is an uncommon, but not rare, neoplasm included in the WHO classification of endometrial carcinomas.1, 24, 25, 26 It is defined as ‘a tumour composed of medium or large cells with complete absence of squamous or glandular differentiation and with absent or minimal (<10%) neuroendocrine differentiation’. It may occur in pure form or in combination with and probably as a result of dedifferentiation in a low-grade (grade 1 or 2) endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Misdiagnosis of dedifferentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma as a carcinosarcoma may occur, given the characteristic sharp demarcation between the two components with the undifferentiated carcinoma being misinterpreted as undifferentiated sarcoma. In the former, the epithelial component is low grade whereas in carcinosarcoma, if endometrioid, it is typically high grade. The undifferentiated component in dedifferentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma usually is composed of non-cohesive cells and is typically positive, albeit typically very focally, with cytokeratins and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA); even when there is only focal positive staining with these markers, it is characteristically intense. Undifferentiated endometrial carcinomas and dedifferentiated endometrioid adenocarcinomas may be associated with mismatch repair (MMR) abnormalities, which is not usually the case with carcinosarcomas, although there is loss of staining in as much as 6% of tumours in one study.27

A small percentage of uterine malignancies with a malignant epithelial and mesenchymal component may be true collision tumours (for example, an endometrioid adenocarcinoma admixed with a low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma or a leiomyosarcoma) or arise as a result of malignant transformation within the epithelial element of an adenosarcoma (see below).28 Whether these represent true carcinosarcomas or collision tumours remain not clear.

Rare endometrial adenocarcinomas, especially those of endometrioid type, may rarely contain benign heterologous elements, including mature bone (most commonly) and adipose tissue,29 these should not be misdiagnosed as carcinosarcoma.

Carcinosarcomas of the uterine cervix are much less common than its uterine corpus counterpart. The main differences include the following: (1) the epithelial component is more likely to be squamous, adenoid cystic, adenoid cystic-like or adenoid basal in type (Figure 5),30 (2) the mesenchymal component may comprise undifferentiated sarcoma, fibrosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma or heterologous elements such as chondrosarcoma or rhabdomyosarcoma may be present, but the latter are rare and (3) they are often p16 positive (as they are HPV related). Some carcinosarcomas of the uterine cervix may be of mesonephric origin.31 Before making a diagnosis of a primary carcinosarcoma of the cervix, spread from a uterine corpus primary should be excluded. Carcinosarcoma of the cervix with a squamous element should be distinguished from squamous carcinoma with a spindle cell component (spindle cell squamous carcinoma). In contrast to carcinosarcoma, spindle cell squamous carcinoma shows merging from conventional to spindled areas. In addition, the spindle cell component is positive for p63 in the spindle cell elements, which may assist in the diagnosis, although expression of these markers is often absent or markedly reduced in the spindle cells.32

Key practice points

-

On histologic examination, the diagnosis of carcinosarcoma is made in the presence of high-grade malignant epithelial and mesenchymal components typically showing a sharp demarcation.

-

Carcinosarcomas should be staged similarly to endometrial carcinomas and not using uterine sarcoma staging systems as their pattern of spread is akin to other high-grade enodmetrial carcinomas.

-

Percentages and types of the epithelial and mesenchymal elements should be included on the pathology report.

-

In stage I uterine carcinosarcomas, adverse prognostic indicators include serous and clear cell morphology and the presence of a heterologous mesenchymal elements.

-

When confronted with a low-grade ‘biphasic’ tumour, consider the possibility of endometrioid adenocarcinoma with corded and hyalinized elements/endometrioid adenocarcinoma with spindle cell elements and dedifferentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma.

-

Extensive sampling in an undifferentiated sarcoma or pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma may reveal areas diagnostic of carcinosarcoma.

Mullerian Adenosarcoma

The WHO definition of adenosarcoma is ‘a mixed epithelial and mesenchymal tumour in which the epithelial component is benign or atypical and the stromal component is low-grade malignant’.1 Adenosarcomas are uncommon and are the third commonest subtype of uterine sarcoma after leiomyosarcoma and low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma. In a recent population-based study from Norway, adenosarcomas accounted for 5.5% of uterine sarcomas.33 Adenosarcoma is generally considered as a neoplasm of low malignant potential, capable of local recurrence and occasionally distant metastasis. The uterine corpus is the most common location in the female genital tract, but these neoplasms also arise in the cervix, ovary or vagina, or more rarely in the peritoneum.34, 35, 36, 37

Clinical Features

Uterine adenosarcoma occurs in all age groups, but is most common in women after menopause. In the largest reported series, tumours occurred in patients 14–89 (median 58) years.35 The most common presenting symptom is abnormal vaginal bleeding, but some patients present with pelvic pain, abdominal mass or vaginal discharge. Some patients may have a history of recurrent endometrial or cervical polyps. An association with tamoxifen, hyperestrogenism and prior pelvic radiation has been reported.38 However, these may be coincidental associations and there are no proven aetiological factors.

Pathological Features

Adenosarcoma most commonly arises from the endometrium, sometimes involving the lower uterine segment, but some may arise in the cervix or myometrium from adenomyosis.34, 35, 36, 37, 39 The uterine cavity is typically filled and distended by a polypoid lobulated, spongy or rubbery, mass which may project through the cervical os. The cut surface may show variably sized cysts or clefts (Figure 6). There is often focal haemorrhage and necrosis. Some neoplasms form multiple polyps.

Histologically, the mixed nature of the tumour is exemplified by the presence of both epithelial and stromal elements, the latter predominating. At low power magnification, the tumour often has a phyllodes-like (leaf-like or club-like) architecture (Figure 7). The epithelial elements usually consist of glands, which may be dilated or slit-like with a phyllodes-like appearance, lined by cuboidal or low columnar cells. In most cases, the epithelium is endometrioid and resembles proliferative endometrium, although ciliated, mucinous and squamous epithelium may also be seen. Uncommonly, the epithelial component exhibits glandular complexity resembling atypical hyperplasia/endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia or carcinoma. The latter is usually a low-grade endometrioid carcinoma.28 The stromal component, which is typically low grade, is composed of spindled and/or round cells with scant cytoplasm, but rarely can be high grade. Intraglandular protrusions of stroma and the manner in which the stromal cells, which often resemble endometrial stromal cells, concentrate around or beneath the glandular elements (‘periglandular cuffing’) are characteristic (Figure 8). The ‘cuffing’ may be very thin (and thus overlooked) but is where nuclear atypia and mitotic activity are typically found (Figure 9). Although a mitotic rate of ≥2 per 10 high power fields (HPFs) is often seen, some tumours have a lower mitotic rate and should be diagnosed as adenosarcoma if the tumour has the characteristic aforementioned features as reflected in the 2014 WHO classification.1

Most adenosarcomas contain exclusively homologous mesenchymal elements, including smooth muscle with spindle or epithelioid morphology.38 Sex cord-like elements, composed of nests, cords, solid or hollow tubules, and identical to those seen in endometrial stromal neoplasms, may be present within the mesenchymal component; these may be positive for sex cord markers, such as inhibin and calretinin (Figure 10).40 The sex cord-like elements may contain abundant eosinophilic or foamy cytoplasm. Rarely, there is extensive overgrowth of sex cord-like elements within an adenosarcoma.41, 42 Approximately 25% of these tumours may contain heterologous stromal elements, most commonly rhabdomyoblasts and fetal-type cartilage, and rarely lipoblasts.40 The heterologous elements usually represent a minor component of the stroma, but are occasionally widespread. Extensive hyalinization, myxoid change or decidualization have been reported.41

The majority of adenosarcomas are confined to the endometrium or cervical mucosa. Approximately 15% invade into the myometrium, usually the inner half, or cervical stroma. The myoinvasive component usually consists of both epithelial and stromal elements, but it may only be composed of sarcoma, which may be higher grade. Deep invasion is much more common with sarcomatous overgrowth (see below). Vascular invasion is rare but occasionally occurs, especially with deep myometrial invasion or sarcomatous overgrowth.

Adenosarcoma with Sarcomatous Overgrowth

Sarcomatous overgrowth is defined as the presence of pure sarcoma (without epithelial elements) comprising >25% of the tumour.1 The sarcoma is typically high grade and may be composed of rhabdomyosarcoma or undifferentiated sarcoma (Figure 11). Rarely, the sarcoma in sarcomatous overgrowth may be low grade. Sarcomatous overgrowth is typically associated with deep myometrial and vascular invasion, and is the most important prognostic factor.42

Ancillary Studies

The low-grade stromal component typically expresses oestrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), CD10, WT1 and smooth muscle actin, and there is low MIB1 proliferation index.43 Less frequently, there is androgen receptor, AE1/AE3, desmin and calretinin positivity. In areas of sarcomatous overgrowth (high-grade), the mesenchymal component exhibits a higher MIB1 proliferation index and there is usually loss of expression of ER, PR and CD10, the immunophenotype being similar to that of an undifferentiated uterine sarcoma. Areas of rhabdomyosarcoma express desmin and skeletal muscle markers (myogenin and myoD1). Sex cord-like elements may express inhibin, calretinin and other sex cord markers.36

A recent investigation of the underlying molecular events in adenosarcoma using next-generation sequencing found MDM2 and CDK4 amplification with protein overexpression in some tumours. Alterations in the PIK3CA/AKT/PTEN pathway were also found, but Tp53 mutations were uncommon. ATRX mutations and MYBL1 amplification were only seen in tumours with sarcomatous overgrowth.44

Prognosis

Patients with adenosarcoma have a generally good prognosis unless the tumour shows deep myometrial invasion or has sarcomatous overgrowth. Recurrences, which occur in 20–30% of patients, are usually confined to the vagina, pelvis or abdomen.35 They are most commonly composed solely of sarcoma which is usually, but not always, of higher grade than the mesenchymal component in the original neoplasm. In some cases, the recurrence is biphasic in appearance. Distant metastasis, which occurs infrequently, is almost always composed of pure sarcoma. There may be late recurrences; therefore, long term follow-up is needed.

Staging

Adenosarcomas have a separate staging system than leiomyosarcomas and endometrial stromal sarcomas.45 Stage I adenosarcomas are confined to the uterus (corpus and cervix) with substages of IA, IB and IC (tumour limited to endometrium/endocervix with no myometrial invasion, less than or equal to half myometrial invasion, more than half myometrial invasion, respectively). Some Mullerian adenosarcomas with unusual growth patterns may be difficult to stage, in particular, when they involve adenomyosis or arise in mural adenomyomas.39

Differential Diagnosis

Adenofibroma

One of the main problems in differential diagnoses of adenosarcoma is adenofibroma. Using the 2003 WHO definition, adenosarcoma was distinguished from adenofibroma by the presence of a stromal mitotic count of 2 or more per 10 HPFs, significant stromal cellularity with periglandular cuffing and more than mild nuclear atypia of the stromal cells.46 However, as discussed, this degree of mitotic activity is not always present in adenosarcomas and this is reflected in the 2014 WHO Classification where no mitotic cut off is given to distinguish between adenosarcoma and adenofibroma.1 Adenosarcoma is much more common than adenofibroma, and there is controversy as to whether adenofibroma exists.36, 47 A confident diagnosis of adenofibroma cannot be made on a biopsy or polypectomy specimen because adenosarcoma cannot be excluded unless the whole tumour is available for histological examination. Using these strict criteria, a diagnosis of adenofibroma is made only rarely and, for practical purposes, this diagnosis cannot be made on a biopsy specimen. An argument can be made that all adenofibromas are in fact low-grade or well-differentiated adenosarcomas since even in the absence of mitotic activity, cases may recur or rarely even metastasise.47 It has been suggested that adenofibromas and adenosarcomas should be combined into a single neoplastic category and the term adenofibroma dropped. Although the entity of adenofibroma is retained in the 2014 WHO classification, this diagnosis should be made sparingly.1

Undifferentiated sarcoma or pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma

In adenosarcoma with sarcomatous overgrowth, large areas of the tumour may morphologically be in keeping with undifferentiated sarcoma or pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma. Extensive sampling, however, should be done and may reveal areas diagnostic of adenosarcoma.

Carcinosarcoma

In contrast to low-grade adenosarcoma, carcinosarcoma contains clearly malignant epithelial elements in addition to the sarcomatous component. The stromal component of almost all carcinosarcomas is high grade and much more pleomorphic than in most adenosarcomas and lacks the periglandular cuffing of increased stromal cellularity that is characteristic of adenosarcoma. Occasional carcinosarcomas have a low-power architecture that raises the possibility of an adenosarcoma; however, this is usually a focal finding and on high-power examination the epithelium exhibits obvious malignant cytological features.

Endometrial and cervical polyps

Occasional endocervical or endometrial polyps contain areas, which raise the possibility of an adenosarcoma.48 Features that overlap with those seen in adenosarcoma include the focal findings of (1) the ‘phyllodes-like’ architecture, (2) intraglandular stromal protrusions and/or (3) increased cellularity surrounding the glands (Figure 12a). Some of these features may be seen in association with tamoxifen therapy. Such cases are best reported as ‘endocervical or endometrial polyps with unusual features’. It recently has been shown that outcome is always uneventful.48 Some endometrial polyps may have a uniformly cellular stroma and may contain abundant smooth muscle (adenomyomtous polyp) or atypical stromal cells with a symplastic appearance (Figure 12b).49 These findings have no clinical significance and should not result in the misdiagnosis as adenosarcoma.

Atypical polypoid adenomyoma

This biphasic tumour lacks the phyllodes-like architecture and periglandular cuffing, and the stromal component shows smooth muscle or myofibroblastic differentiation. The epithelial elements usually show greater architectural complexity than is seen in adenosarcoma as well as foci of squamous differentiation, in the form of morules, which sometimes show central necrosis. Furthermore, at low power, a vaguely lobular architecture may be noted.50

Low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma with glandular differentiation

Low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma may occasionally have endometrioid glandular differentiation and thus raise the differential of an adenosarcoma;51 however, endometrial stromal sarcomas have a permeative as opposed to destructive myometrial invasion, the myoinvasive component has a more uniform appearance, and it lacks periglandular stromal cuffing, the phyllodes-like architecture or prominent epithelial Mullerian metaplasia.52

Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma

Features of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma that may overlap with low-grade Mullerian adenosarcoma include the findings of small blue cells that concentrate under the surface epithelium and around glands mimicking periglandular cuffing, fetal cartilage and rhabdomyoblasts, although cartilage is more common in the cervix than in the corpus or other locations.53, 54 Distinguishing features include high-grade cytologic atypia as well as mitotic activity and apoptosis in the small cells, alternating areas of hyper- and hypocellularity and paucity of Müllerian glands which are entrapped and not part of the neoplasm and do not show the typical phyllodes-like architecture. The hypocellular areas are often myxoid or edematous and may have aggregates of cells with more abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm including cross striations. In contrast to adenosarcoma, embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma occurs more frequently in the cervix than in the uterine corpus. Occasionally, foci resembling alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma or collections of pleomorphic cells with multilobated nuclei are present.55 Hyaline globules may be seen. There are commonly areas of haemorrhage with extravasated erythrocytes or necrosis. Nuclear staining with skeletal muscle markers (myogenin and myoD1) assists in diagnosis but typically only a minor proportion of the nuclei are immunoreactive. Desmin is usually positive but smooth muscle actin and h-caldesmon are typically negative. Hormone receptors (ER and PR) are generally negative in contrast to typical areas of adenosarcoma. Of note, there is a rare association between cervical embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumour, cystic nephroma, thyroid goitres, pleuropulmonary blastoma and other embryonic neoplasms, and this is secondary to underlying somatic or germline DICER1 mutation.50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59

Key practice points: uterine adenosarcoma

-

1

The diagnosis of adenofibroma should be made sparingly, if at all, as tumours classified as adenofibroma can behave in a similar manner to adenosarcoma.

-

2

Occasionally, a diagnosis of adenosarcoma can be made in the absence of mitotic activity in the mesenchymal component if other characteristic histological features are present.

-

3

The two most important adverse prognostic features in adenosarcoma are deep myometrial invasion and sarcomatous overgrowth.

-

4

The mesenchymal component of most adenosarcomas is ‘low grade’ but in areas of sarcomatous overgrowth it is typically ‘high grade’ resembling undifferentiated sarcoma or pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma.

-

5

Before making the diagnosis of adenosarcoma, exclude an embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma when the cells surrounding the glands show a high mitotic rate and cytologic atypia.

-

6

Occasional endometrial or cervical polyps have focal areas that raise the possibility of an adenosarcoma; however, follow-up in such cases is uneventful.

-

7

Extensive sampling in an undifferentiated sarcoma or pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma may reveal areas diagnostic of adenosarcoma.

Adenomyomas

Atypical Polypoid Adenomyoma (Atypical Polypoid Adenomyofibroma)

Atypical polypoid adenomyoma (APA) is defined as a biphasic tumour composed of endometrioid-type glands embedded in a myomatous or fibromyomatous stroma.50, 60, 61, 62 Most patients are premenopausal or perimenopausal (average age 40 years) and present with abnormal uterine bleeding, usually menorrhagia. Rare examples have been described in patients with Turners syndrome who have been prescribed unopposed oestrogens.63

Atypical polypoid adenomyoma is most commonly located in the lower uterine segment, although may involve fundus, uterine body or even endocervix. The tumour is typically polypoid with a broad-base, although the polypoid nature may not be grossly obvious (especially in smaller lesions) or may have a predominant endophytic growth.

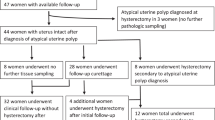

At low-power examination, the tumour shows endometrioid-type glands that may be crowded, or widely separated and haphazardly arranged, with a vague lobular architecture. The endometrioid glands may be tubular or show complex branching and not infrequently contain squamous morules that may show central necrosis (Figure 13b). The glands exhibit mild or, at most, moderate cytological atypia (Figure 13a). Occasionally, ciliated or mucinous epithelium may be seen. The glands are set in an abundant myoid or fibromyomatous stroma which is often arranged in short interlacing fascicles with minimal cytologic atypia and only occasional mitotic figures. Significant glandular crowding may occur and may be indistinguishable from a grade I endometrioid adenocarcinoma. The term atypical polypoid adenomyoma of low malignant potential has been suggested for lesions with marked architectural complexity,61 but this term is not in widespread use and is not recommended. However, in such cases, if the tumour is not completely excised, then the risk of recurrence is higher. Moreover, these are more likely to be associated with atypical hyperplasia and/or endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the non-polypoid endometrium.

Atypical polypoid adenomyoma with low architectural complexity, if completely resected, is typically benign. Recurrence may occur if there is incomplete excision or there is complex architecture bordering on endometrial adenocarcinoma, which was estimated at 8.8% in one meta-analysis.64 Thus, hysterectomy is the treatment of choice; however, in a patient who wishes to maintain fertility, and a confident diagnosis of APA has been made by complete excision, the option of hormonal therapy with close follow-up can be considered. Successful pregnancies have ensued in patients managed in this way.

The most important differential diagnosis, and one which is especially likely on a biopsy, is an endometrioid adenocarcinoma exhibiting myometrial invasion or associated with a prominent desmoplastic stroma. This is an obviously important distinction as most APAs have a benign behaviour with a potential for conservative management especially in child-bearing women. The finding of a vague lobular architecture, short interlacing fascicles of the stromal component (in contrast to myometrium) and an absence of marked cytologic atypia favours APA. Furthermore, in curettings or biopsies from an APA there are usually also fragments of background endometrium which are unusual to obtain in a myoinvasive endometrial carcinoma. However, this distinction is not always obvious, and as mentioned earlier, APA may have complex architecture and cytologic atypia bordering on carcinoma. Immunohistochemistry is of limited value in this distinction as the stromal component of APA and myometrium infiltrated by carcinoma are both desmin and smooth muscle actin positive. It has been suggested that CD10 may be helpful as it is absent in the stromal component of APA, while the myoinvasive glands of endometrioid adenocarcinoma are typically surrounded by a thin rim of CD10 positive stromal cells (‘fringe-like’ staining pattern).65 h-caldesmon can be of use as it is strongly expressed in myometrial smooth muscle invaded by endometrioid adenocarcinoma while the myomatous or fibromyomatous stroma of APA is usually negative.66 Less commonly, the differential diagnosis includes an endometrial polyp with variable amounts of smooth muscle (adenomyomatous polyp) or an endometrioid-type adenomyoma.67, 68, 69 The former typically has the smooth muscle component near the central fibrovascular core with the endometrial glands typically pushed towards the periphery. Endometrioid-type adenomyoma is composed of benign appearing endometrial glands surrounded by benign-appearing endometrial stroma (which is lacking in APA) which in turn is surrounded by smooth muscle (the latter which is the predominant component). Rarely, a carcinosarcoma enters into the differential diagnosis of atypical polypoid adenomyoma because of the admixture of epithelial and stromal elements. However, both epithelial and mesenchymal components of a carcinosarcoma are obviously malignant and typically high grade.

There is limited information concerning the molecular events in atypical polypoid adenomyoma but abnormalities identified include MLH-1 promoter hypermethylation, PTEN and KRAS mutations and microsatellite instability,70, 71 findings that are similar to the molecular abnormalities seen in endometrial atypical hyperplasia and endometrioid adenocarcinoma. These findings coupled with the common association of APA with atypical hyperplasia and/or endometrial carcinoma suggest the possibility that APA may be a localized form of atypical hyperplasia.71

Endometrioid-Type Adenomyoma

The term endometrioid-type adenomyoma is used for a biphasic proliferation in which benign endometrioid type glands, sometimes with minor foci of ciliated, mucinous or squamous metaplasia, are surrounded by variable amounts of endometrioid stroma which is in turn surrounded by mature smooth muscle (predominant component; Figure 14). They may be polypoid or intramyometrial. These tumours may also occur in extrauterine locations, especially in the broad ligament.69 Glandular changes uncommonly seen include crowding and dilation. The smooth muscle component, while usually normocellular and morphologically bland, can be cellular, exhibit hydropic change, symplastic type nuclear atypia or contain adipose tissue.69 When polypoid, it may be confused with atypical polypoid adenomyoma; however, the latter has a more prominent glandular component that may show architectural complexity, lacks endometrial stroma around the glands and shows a much less prominent smooth muscle component that does not show any morphologic features of leiomyoma variants. Some endometrial polyps contain smooth muscle (adenomyomatous polyps); however, it is often in close proximity to thick-walled blood vessels and centrally located while glands tend to be at the periphery of the polyp, close to the surface.67, 68

Endocervical-Type Adenomyoma

Adenomyomas of endocervical type are uncommon neoplasms, and usually occur in women of reproductive or postmenopausal age.72, 73 They vary in size and are most commonly polypoid and project from the mucosal surface of the cervix. Rarely, they may be intramural or exophytic but are always grossly well circumscribed, usually grey-white to tan and may contain small cysts. Histologically, they are composed of bland mucinous glands of endocervical type, often with a somewhat lobular arrangement, embedded in a stroma containing abundant smooth muscle (Figure 15). Some of the glands may be dilated. Tubal, endometrioid or squamous epithelium may be occasionally seen. There is often a thin rim of fibrous tissue surrounding the glands, which is in turn surrounded by mature smooth muscle. Other findings, which are occasionally seen, include gland rupture with mucin extravasation, small intraglandular papillary proliferations (adenofibroma-like) and symplastic change in the smooth muscle component.72, 73 These are benign lesions but occasionally persist or recur following local excision.

The main differential diagnoses are adenoma malignum (well-differentiated gastric type adenocarcinoma) and lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia when dealing with small samples (biopsy). Endocervical adenomyoma and adenoma malignum may be confused, because both have well-differentiated glands and both often show a branching architecture of the glands. Furthermore, in many areas of adenoma malignum the well differentiated glands do not exhibit a stromal reaction. Gross circumscription, orderly arrangement of the glands without associated desmoplastic reaction or significant nuclear atypia and abundance of smooth muscle is helpful in excluding adenoma malignum.73 Lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia may be considered in the differential with endocervical adenomyoma as both share similar morphology of the glandular component and show lobular growth. However, lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia is not polypoid, is more likely to be an incidental microscopic finding and lacks a prominent smooth muscle component. ER may be useful in that the glands in endocervical adenomyoma are positive while adenoma malignum and lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia (part of the spectrum of ‘gastric-type’ endocervical glandular lesions) are typically negative.74

Intravenous Adenomyomatosis

A small series of intravenous/intravascular leiomyomatosis containing a component of ‘entrapped’ endometrioid type glands with surrounding stroma (intravenous adenomyomatosis) has been reported (Figure 16).75 All patients had associated leiomyomata and adenomyosis. The smooth muscle component is usually of conventional type but occasionally symplastic change or adipose tissue (lipoleiomyoma) may be noted. The differential diagnosis may include adenomyosis with vascular involvement (however, this is typically an incidental microscopic finding), low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma with glandular differentiation (however, this tumour shows a predominance of endometrial-type stroma) and adenosarcoma (which typically displays characteristic biphasic growth often with phyllodes-type glands and periglandular cuffing).

Key practice points: mixed epithelial and mesenchymal neoplasms with a prominent smooth muscle component

-

1

Do not misdiagnose atypical polypoid adenomyoma (APA) as a myoinvasive endometrioid adenocarcinoma on biopsy material. Look for a vague lobular arrangement of the endometrial type glands, squamous morular differentiation often with central necrosis and background benign endometrium that will favour an APA.

-

2

H-caldesmon and CD10 staining may be useful in distingushing atypical polypoid adenomyoma from myoinvasive endometrioid adenocarcinoma.

-

3

Before making a diagnosis of adenoma malignum, consider the possibility of endocervical adenomyoma. Correlate clinical, gross (circumscription) and microscopic appearance. If there is ER positivity in the neoplastic glands, then this favours the diagnosis of adenoyoma.

References

Kurman RJ . International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization. WHO Classification of Tumours of Female Reproductive Organs, 4th (edn). International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2014.

Peters WM, Wells M, Bryce FC . Mullerian clear cell carcinofibroma of the uterine corpus. Histopathology 1984;8:1069–1078.

Thompson M, Husemeyer R . Carcinofibroma—a variant of the mixed Mullerian tumour. Case report. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1981;88:1151–1155.

McCluggage WG, Abdulkader M, Price JH et al. Uterine carcinosarcomas in patients receiving tamoxifen. A report of 19 cases. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2000;10:280–284.

Seidman JD, Kumar D, Cosin JA et al. Carcinomas of the female genital tract occurring after pelvic irradiation: a report of 15 cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2006;25:293–297.

Pecorelli S . Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2009;105:103–104.

Rossi A . Carcinosarcoma (malignant mixed Mullerian tumor) arising in an endometrial polyp. Report of a case. Pathologica 1999;91:282–285.

Kahner S, Ferenczy A, Richart RM . Homologous mixed Mullerian tumors (carcinosarcomal) confined to endometrial polyps. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1975;121:278–279.

Euscher ED, Deavers MT, Lopez-Terrada D et al. Uterine tumors with neuroectodermal differentiation: a series of 17 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:219–228.

Shokeir MO, Noel SM, Clement PB . Malignant mullerian mixed tumor of the uterus with a prominent alpha-fetoprotein-producing component of yolk sac tumor. Mod Pathol 1996;9:647–651.

Amant F, Moerman P, Davel GH et al. Uterine carcinosarcoma with melanocytic differentiation. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2001;20:186–190.

McCluggage WG . Malignant biphasic uterine tumours: carcinosarcomas or metaplastic carcinomas? J Clin Pathol 2002;55:321–325.

McCluggage WG . Uterine carcinosarcomas (malignant mixed Mullerian tumors) are metaplastic carcinomas. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2002;12:687–690.

Sreenan JJ, Hart WR . Carcinosarcomas of the female genital tract. A pathologic study of 29 metastatic tumors: further evidence for the dominant role of the epithelial component and the conversion theory of histogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol 1995;19:666–674.

de Jong RA, Nijman HW, Wijbrandi TF et al. Molecular markers and clinical behavior of uterine carcinosarcomas: focus on the epithelial tumor component. Mod Pathol 2011;24:1368–1379.

Wada H, Enomoto T, Fujita M et al. Molecular evidence that most but not all carcinosarcomas of the uterus are combination tumors. Cancer Res 1997;57:5379–5385.

Stewart CJ, McCluggage WG . Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in carcinomas of the female genital tract. Histopathology 2013;62:31–43.

Chiyoda T, Tsuda H, Tanaka H et al. Expression profiles of carcinosarcoma of the uterine corpus-are these similar to carcinoma or sarcoma? Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2012;51:229–239.

Lopez-Garcia MA, Palacios J . Pathologic and molecular features of uterine carcinosarcomas. Semin Diagn Pathol 2010;27:274–286.

Ferguson SE, Tornos C, Hummer A et al. Prognostic features of surgical stage I uterine carcinosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2007;31:1653–1661.

McCluggage WG, Colgan T, Duggan et al. Data set for reporting of endometrial carcinomas: recommendations from the International Collaboration on Cancer Reporting (ICCR) between United Kingdom, United States, Canada, and Australasia. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2013;32:45–65.

Murray SK, Clement PB, Young RH . Endometrioid carcinomas of the uterine corpus with sex cord-like formations, hyalinization, and other unusual morphologic features: a report of 31 cases of a neoplasm that may be confused with carcinosarcoma and other uterine neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:157–166.

Tornos C, Silva EG, Ordonez NG et al. Endometrioid carcinoma of the ovary with a prominent spindle-cell component, a source of diagnostic confusion. A report of 14 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1995;19:1343–1353.

Silva EG, Deavers MT, Malpica A . Undifferentiated carcinoma of the endometrium: a review. Pathology 2007;39:134–138.

Altrabulsi B, Malpica A, Deavers MT et al. Undifferentiated carcinoma of the endometrium. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:1316–1321.

Silva EG, Deavers MT, Bodurka DC et al. Association of low-grade endometrioid carcinoma of the uterus and ovary with undifferentiated carcinoma: a new type of dedifferentiated carcinoma? Int J Gynecol Pathol 2006;25:52–58.

Hoang LN, Ali RH, Lau S et al. Immunohistochemical survey of mismatch repair protein expression in uterine sarcomas and carcinosarcomas. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2014;33:483–491.

Seidman JD, Chauhan S . Evaluation of the relationship between adenosarcoma and carcinosarcoma and a hypothesis of the histogenesis of uterine sarcomas. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2003;22:75–82.

Nogales FF, Gomez-Morales M, Raymundo C et al. Benign heterologous tissue components associated with endometrial carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1982;1:286–291.

Clement PB, Zubovits JT, Young RH et al. Malignant Mullerian mixed tumors of the uterine cervix: a report of nine cases of a neoplasm with morphology often different from its counterpart in the corpus. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1998;17:211–222.

Clement PB, Young RH, Keh P et al. Malignant mesonephric neoplasms of the uterine cervix. A report of eight cases, including four with a malignant spindle cell component. Am J Surg Pathol 1995;19:1158–1171.

Houghton O, McCluggage WG . The expression and diagnostic utility of p63 in the female genital tract. Adv Anat Pathol 2009;16:316–321.

Abeler VM, Royne O, Thoresen S et al. Uterine sarcomas in Norway. A histopathological and prognostic survey of a total population from 1970 to 2000 including 419 patients. Histopathology 2009;54:355–364.

Zaloudek CJ, Norris HJ . Adenofibroma and adenosarcoma of the uterus: a clinicopathologic study of 35 cases. Cancer 1981;48:354–366.

Clement PB, Scully RE . Mullerian adenosarcoma of the uterus: a clinicopathologic analysis of 100 cases with a review of the literature. Hum Pathol 1990;21:363–381.

McCluggage WG . Mullerian adenosarcoma of the female genital tract. Adv Anat Pathol 2010;17:122–129.

Eichhorn JH, Young RH, Clement PB et al. Mesodermal (Mullerian) adenosarcoma of the ovary: a clinicopathologic analysis of 40 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:1243–1258.

Clement PB, Oliva E, Young RH . Mullerian adenosarcoma of the uterine corpus associated with tamoxifen therapy: a report of six cases and a review of tamoxifen-associated endometrial lesions. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1996;15:222–229.

Clarke BA, Mulligan AM, Irving JA et al. Mullerian adenosarcomas with unusual growth patterns: staging issues. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2011;30:340–347.

Clement PB, Scully RE . Mullerian adenosarcomas of the uterus with sex cord-like elements. A clinicopathologic analysis of eight cases. Am J Clin Pathol 1989;91:664–672.

Manipadam MT, Munemane A, Emmanuel P . Ovarian adenosarcoma with extensive deciduoid morphology arising in endometriosis: a case report. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2008;27:398–401.

Verschraegen CF, Vasuratna A, Edwards C et al. Clinicopathologic analysis of Mullerian adenosarcoma: the M.D. Anderson cancer center experience. Oncol Rep 1998;5:939–944.

Soslow RA, Ali A, Oliva E . Mullerian adenosarcomas: an immunophenotypic analysis of 35 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:1013–1021.

Howitt BE, Sholl LM, Dal Cin P . Targeted genomic analysis of Mullerian adenosarcoma. J Pathol 2015;235:37–49.

Prat J . FIGO staging for uterine sarcomas. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2009;104:177–178.

Tavassoli FA, Devilee P, Tavassoli FA International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Breast and Female Genital Organs. IARC Press; Oxford University Press (distributor): Lyon: Oxford, 2003.

Gallardo A, Prat J . Mullerian adenosarcoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 55 cases challenging the existence of adenofibroma. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:278–288.

Howitt BE, Quade BJ, Nucci MR . Uterine polyps with features overlapping with those of Mullerian adenosarcoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 29 cases emphasizing their likely benign nature. Am J Surg Pathol 2015;39:116–126.

Tai LH, Tavassoli FA . Endometrial polyps with atypical (bizarre) stromal cells. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:505–509.

Young RH, Treger T, Scully RE . Atypical polypoid adenomyoma of the uterus. A report of 27 cases. Am J Clin Pathol 1986;86:139–145.

McCluggage WG, Ganesan R, Herrington CS . Endometrial stromal sarcomas with extensive endometrioid glandular differentiation: report of a series with emphasis on the potential for misdiagnosis and discussion of the differential diagnosis. Histopathology 2009;54:365–373.

Clement PB, Scully RE . Endometrial stromal sarcomas of the uterus with extensive endometrioid glandular differentiation: a report of three cases that caused problems in differential diagnosis. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1992;11:163–173.

McClean GE, Kurian S, Walter N et al. Cervical embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma and ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumour: a more than coincidental association of two rare neoplasms? J Clin Pathol 2007;60:326–328.

Li RF, Gupta M, McCluggage WG et al. Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (botryoid type) of the uterine corpus and cervix in adult women: report of a case series and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol 2013;37:344–355.

Houghton JP, McCluggage WG . Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of the cervix with focal pleomorphic areas. J Clin Pathol 2007;60:88–89.

Daya DA, Scully RE . Sarcoma botryoides of the uterine cervix in young women: a clinicopathological study of 13 cases. Gynecol Oncol 1988;29:290–304.

Golbang P, Khan A, Scurry J et al. Cervical sarcoma botryoides and ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor. Gynecol Oncol 1997;67:102–106.

Dehner LP, Jarzembowski JA, Hill DA . Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterine cervix: a report of 14 cases and a discussion of its unusual clinicopathological associations. Mod Pathol 2012;25:602–614.

Foulkes WD, Bahubeshi A, Hamel N et al. Extending the phenotypes associated with DICER1 mutations. Hum Mutat 2011;32:1381–1384.

Soslow RA, Chung MH, Rouse RV et al. Atypical polypoid adenomyofibroma (APA) versus well-differentiated endometrial carcinoma with prominent stromal matrix: an immunohistochemical study. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1996;15:209–216.

Longacre TA, Chung MH, Rouse RV et al. Atypical polypoid adenomyofibromas (atypical polypoid adenomyomas) of the uterus. A clinicopathologic study of 55 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1996;20:1–20.

Mazur MT . Atypical polypoid adenomyomas of the endometrium. Am J Surg Pathol 1981;5:473–482.

Clement PB, Young RH . Atypical polypoid adenomyoma of the uterus associated with Turner’s syndrome. A report of three cases, including a review of ‘estrogen-associated’ endometrial neoplasms and neoplasms associated with Turner’s syndrome. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1987;6:104–113.

Heatley MK . Atypical polypoid adenomyoma: a systematic review of the English literature. Histopathology 2006;48:609–610.

Ohishi Y, Kaku T, Kobayashi H et al. CD10 immunostaining distinguishes atypical polypoid adenomyofibroma (atypical polypoid adenomyoma) from endometrial carcinoma invading the myometrium. Hum Pathol 2008;39:1446–1453.

Horita A, Kurata A, Maeda D et al. Immunohistochemical characteristics of atypical polypoid adenomyoma with special reference to h-caldesmon. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2011;30:64–70.

Gilks CB, Clement PB, Hart WR et al. Uterine adenomyomas excluding atypical polypoid adenomyomas and adenomyomas of endocervical type: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases of an underemphasized lesion that may cause diagnostic problems with brief consideration of adenomyomas of other female genital tract sites. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2000;19:195–205.

Tahlan A, Nanda A, Mohan H . Uterine adenomyoma: a clinicopathologic review of 26 cases and a review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2006;25:361–365.

Stewart CJ, Leung YC, Mathew et al. Extrauterine adenomyoma with atypical (symplastic) smooth muscle cells: a report of 2 cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2009;28:23–28.

Ota S, Catasus L, Matias-Guiu X et al. Molecular pathology of atypical polypoid adenomyoma of the uterus. Hum Pathol 2003;34:784–788.

Nemejcova K, Kenny SL, Laco J et al. Atypical polypoid adenomyoma of the uterus: an immunohistochemical and molecular study of 21 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2015;39:1148–1155.

Gilks CB, Young RH, Clement PB et al. Adenomyomas of the uterine cervix of endocervical type: a report of ten cases of a benign cervical tumor that may be confused with adenoma malignum [corrected]. Mod Pathol 1996;9:220–224.

Casey S, McCluggage WG . Adenomyomas of the uterine cervix: Report of a cohort including endocervical and novel variants [corrected. Histopathology 2015;66:420–429.

Mikami Y, McCluggage WG . Endocervical glandular lesions exhibiting gastric differentiation: an emerging spectrum of benign, premalignant, and malignant lesions. Adv Anat Pathol 2013;20:227–237.

Hirschowitz L, Mayall FG, Ganesan R et al. Intravascular adenomyomatosis: Expanding the morphologic spectrum of intravascular leiomyomatosis. Am J Surg Pathol 2013;37:1395–1400.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McCluggage, W. A practical approach to the diagnosis of mixed epithelial and mesenchymal tumours of the uterus. Mod Pathol 29 (Suppl 1), S78–S91 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2015.137

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2015.137

This article is cited by

-

The typical polypoid adenomyoma is a special form of endometrial polyp: a case-controlled study with a large sample size

European Journal of Medical Research (2023)

-

Endometriale und weitere seltene uterine Sarkome

Der Pathologe (2022)

-

First report on establishment and characterization of a carcinosarcoma tumour cell line model of the bladder

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Aktuelle WHO-Klassifikation des weiblichen Genitale

Der Pathologe (2021)

-

A subset of epithelioid and spindle cell rhabdomyosarcomas is associated with TFCP2 fusions and common ALK upregulation

Modern Pathology (2020)