Abstract

This review concentrates on three salivary gland tumors that have been accepted in the recent literature as new neoplastic entities: mammary analog secretory carcinoma (MASC), sclerosing polycystic adenoma (SPA) and cribriform adenocarcinoma of tongue and other minor salivary glands (CAMSGs). MASC is a distinctive low-grade malignant salivary cancer that harbors a characteristic chromosomal translocation, t(12;15) (p13;q25) resulting in an ETV6–NTRK3 fusion. SPA is a rare lesion often mistaken histologically for low-grade salivary carcinoma. Previously thought to be a reactive fibroinflammatory process, but recent evidence of clonality, recurrences in up 30%, and dysplastic foci suggest it may be truly neoplastic. CAMSG is a distinct tumor entity that differs from polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma (PLGA) by location (ie, most often arising on the tongue), by prominent nuclear clearing, alterations of the PRKD gene family and clinical behavior with frequent metastases at the time of presentation of the primary tumor. Early metastatic disease seen in most cases of CAMSG associated with indolent behavior makes it a unique neoplasm among all low-grade salivary gland tumors. Salivary glands may give rise to a wide spectrum of different tumors. They are often diagnostically challenging as morphological features often overlap between different entities. Although conventional morphology in combination with immunohistochemical findings still provide the most important clues for diagnosis, recent advances in molecular pathology offer new diagnostic tools in investigating the differential diagnosis, as well as providing potentially valuable prognostic indicators. In the last two decades, several new salivary gland tumor entities have been described, namely MASC, SPA and CAMSGs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Mammary analog secretory carcinoma

Introduction

Mammary analog secretory carcinoma (MASC) of salivary gland origin is a recently described tumor that harbors a characteristic balanced chromosomal translocation,1, 5 t(12;15) (p13;q25) resulting in an ETV6–NTRK3 fusion 6 identical to that in secretory carcinoma of the breast.7 Secretory carcinoma (SC), also known as juvenile breast cancer, is a very rare and distinctive variant of mammary ductal carcinoma, initially described by McDivitt and Stewart in patients ranging from 3 to 15 years.8 Although most cases occur in children or young adults, a significant percentage of SCs arises in elderly patients of both sexes.9 Tognon et al demonstrated that SC of the breast harbors a recurrent balanced chromosomal translocation t(12;15) (p13;q25) ETV6-NTRK3, which leads to a fusion gene, comprising the ETV6 gene on chromosome 12 and the NTRK3 gene on chromosome 15.7 The fusion gene ETV6–NTRK3 encodes for chimeric tyrosine kinase that has been shown to have transformation activity in epithelial and myoepithelial cells of the mouse mammary gland.10

For many years, we began to identify a distinctive hitherto unrecognized neoplasm arising in the salivary glands characterized by morphological and immunohistochemical features strongly reminiscent of those of SC of the breast. These tumors were composed of microcystic and solid areas with abundant vacuolated colloid-like periodic acid–Schiff (PAS)-positive secretory material within the microcystic spaces; and had previously been categorized as either unusual variants of salivary acinic cell carcinoma (AciCC) or cystadenocarcinoma not otherwise specified (NOS).

We initially recognized MASC as an entity different from AciCC on the basis of three major findings.6 First, MASC showed no basophilia in the cytoplasm in any of the constituent cells, this being the hallmark of the serous acinar cells of AciCC resulting from the presence of cytoplasmic zymogen granules. Second, these neoplasms had a completely different immunohistochemical profile, almost always expressing S100 protein, mammaglobin, vimentin, STAT5 and MUC4, all of which were rare in AciCC. Finally, unlike AciCC, most cases of this carcinoma were found to harbor an ETV6–NTRK3 fusion gene because of a t(12;15) (p13,q25), a finding identical to SC of the breast.7 As a result of the morphological similarity and identical fusion transcript ETV6–NTRK3, we therefore proposed the designation 'mammary analog secretory carcinoma (MASC) of salivary gland'.6

The near 100% rate of ETV6 gene rearrangement in MASC has been subsequently confirmed by many other studies.11, 12, 13, 14 Detection of ETV6 by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is technically relatively straightforward and >250 cases of MASC have been published in the last 6 years since its original description in 2010.6

Histological Features

Grossly, MASC is usually a firm rubbery mass, with a white-tan to gray cut surface. Occasionally, on cut surface cystic spaces may be seen, containing yellow-whitish fluid. The borders of the tumors are usually circumscribed but not encapsulated and broad-front invasion within the salivary gland is often present (Figure 1a). Perineural invasion and extension to extraglandular tissues can sometimes occur, but lymphovascular invasion is not usual; similarly, necrosis is not typical.

Mammary analog secretory carcinoma of salivary glands (MASCs). (a) MASC are usually circumscribed but not encapsulated, and broad-front invasion within the salivary gland is often present. (b) The tumors consist of a circumscribed mass divided by thin fibrous septa into lobules composed of microcystic, tubular and solid structures. (c) Less commonly, a prominent fibrosclerotic stroma with isolated tumor cells in small islands or trabeculae are seen mostly in the central part of the tumor. (d) Abundant bubbly secretion is present within microcystic and tubular spaces. (e, f) Occasionally, MASC can be dominated by a single large cyst (e) with multilayered apocrine-like or hobnail epithelial lining (f).

Microscopically, most cases of MASC consist of a circumscribed mass divided by thin fibrous septa (Figure 1b) into lobules composed of microcystic, tubular and solid structures. Less commonly, a prominent fibrosclerotic stroma with isolated tumor cells in small islands or trabeculae are seen mostly in the central part of the tumor (Figure 1c). Abundant bubbly secretion is present within microcystic and tubular spaces (Figure 1d). This secretory material stains positively with mucicarmine, PAS before and after diastase digestion and with Alcian blue. Occasionally, MASC can be dominated by a single large cyst with multilayered apocrine-like or hobnail epithelial lining, and then only a minor part of the tumor displays the characteristic tubular, follicular, macro- and microcystic or papillary architecture, with typical secretions (Figures 1e and f).

The tumor cells have low-grade vesicular round-to-oval nuclei, each with finely granular chromatin and a distinctive centrally located small nucleolus (Figure 1a, inset). The cytoplasm may be pale pink to clear with a granular, vacuolated or foamy appearance. Cellular atypia is generally mild, and mitotic figures mostly rare. Thus, MASC may histologically resemble zymogen granule-poor AciCC, low-grade cribriform cystadenocarcinoma, and adenocarcinoma NOS. In contrast to AciCC, serous acinar differentiation is always absent. High-grade (HG) MASC is characterized by focal proliferation of distinct population of anaplastic cells arranged in solid and trabecular pattern with common perineural invasion (Figure 2a) and comedo-like necrosis (Figure 2b). In contrast to the low-grade MASC, the tumor cells of the HG one display aparent nuclear polymorphism, distinctive nucleoli and they fail to reveal any secretory activity. Invasion of the skin was observed in all three cases.

Mammary analog secretory carcinoma of salivary glands with high-grade transformation (HG-MASC). (a, b) HG-MASC is characterized by focal proliferation of distinct population of anaplastic cells arranged in solid and trabecular pattern with common perineural invasion (a) and comedo-like necrosis (b).

Cytopathologic Features

On fine-needle aspiration, the smears are usually very cellular with sheets and clusters of bland polygonal epithelial cells admixed with bright pink filamentous matrix.15, 16, 17 The majority of cases demonstrate clusters of cells ranging from tight, small acinar-like structures to larger, papillary arborizing and tubuloglandular patterns. The cells have abundant vacuolated cytoplasm, with most having multiple small cytoplasmic vacuoles;15, 16, 17, 18, 19 some of these vacuoles contain mucin. The cytoplasm of other cells is finely granular and strongly eosinophilic. Nuclei are small, round and uniform, with eccentrically located small regular distinctive nucleoli. Extracellular material usually consists of mucin that in some cases is abundant.17 Overall, the fine-needle aspiration features are not specific, and original cytology diagnoses can include low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma,16 low-grade epithelial neoplasm NOS, salivary papillary neoplasm and even benign salivary epithelium.17

Immunohistochemical Findings

MASC is consistently positive for pan-cytokeratin (AE1-AE3 and CAM5.2), CK7, CK8, CK18, CK19, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), S100 protein and vimentin, typically in a strong and diffuse pattern6, 13, 20, 21, 22, 23 (Figure 3a). The tumor cells also show strong positive expression of STAT5a (signal transducer and activator of transcription 5a)6 and mammaglobin (secretory material is also positive)21, 23 (Figure 3b). In addition, in most cases there is significant positivity for gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 (GCDFP-15) (particularly the secretory material), SOX10 and GATA-3 (Figure 3c). Basal cell/myoepithelial cell markers, such as p63, calponin, CK14, smooth muscle actin and CK5/6 are virtually negative as described in our original report.6 Since then, we have observed that although p63 protein is typically absent in the cells of MASC, it may occasionally reveal areas of peripheral staining suggestive of an intraductal MASC component.13, 24 Another important finding is that the DOG1 staining profile in MASC is different from AciCC (Figure 3d). Most cases of MASC are DOG1 negative, whereas most AciCCs demonstrate intense apical membranous staining around lumina and variable cytoplasmic positivity.25 Therefore, mammaglobin and S100 protein are useful markers for MASC6, 13, 23 and the findings are consistent in many reports.14, 21, 22, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 Nevertheless, co-expression of mammaglobin and S100 protein is not specific to MASC, and can be observed also in polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma (PLGA), adenoid cystic carcinoma22, 29 and low-grade salivary duct carcinoma (SDC).32 Salivary carbonic anhydrase VI (CA6) has been recently introduced as a novel marker of AciCC with sensitivity and specificity equal to that of DOG1 in discriminating it from MASC.33 Some have postulated that morphology together with supporting S100 protein/mammaglobin immunoreactivity is sufficient to diagnose MASC and molecular confirmation of ETV6 gene rearrangement is not required;31 this may be true for typical cases, but FISH still remains the gold standard for confirming the diagnosis of MASC in carcinomas with unusual morphology, particularly MASC with HG transformation34, 35, 36 and/or cases with morphology departing from usual appearances.37, 38

Mammary analog secretory carcinoma of salivary glands (MASCs): immunoprofile. (a) MASC is consistently positive S100 in a strong and diffuse pattern. (b) Mammaglobin stains the cells and secretory material. (c) SOX10 is positive within the nuclei in most cells of MASC. (d) MASC is devoid of DOG1 expression in contrast to distinct membranous positivity in acinar cells of normal parotid gland (lower right corner).

Molecular Findings

MASC of salivary glands, similar to SC of the breast, harbors a recurrent balanced chromosomal translocation t(12;15) (p13;q25), which leads to a fusion gene between the ETV6 gene on chromosome 12 and the NTRK3 gene on chromosome 15. The biological consequence of the translocation is the fusion of the transcriptional regulator (ETV6) with membrane receptor kinase (NTRK3) that activates kinase through ligand independent dimerization and thus promote cell proliferation and survival. The presence of the ETV6–NTRK3 fusion gene has not been demonstrated in any other salivary gland tumor so far.6 Interestingly, the same translocation, ETV6-NTRK3, can be seen not only in SC of breast,7 but also in infantile fibrosarcoma,39, 40 congenital mesoblastic nephroma,41, 42 some hematopoietic malignancies,43 ALK-negative inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors44 and in radiation-induced papillary thyroid carcinoma.45

For several years, we have been aware of a number of MASC cases positive for the ETV6 gene split as visualized by FISH, but in which the classical ETV6–NTRK3 fusion transcript (exon 5–exon 15 junction) was not detected by standard reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).38 Recent studies indicated that ETV6 may fuse with genes other than NTRK3, or a subset of MASC cases may display atypical exon junctions ETV6-NRTK3.37, 38 Interestingly, these atypical molecular features may be associated with more infiltrative histological features of MASC, and less favorable clinical outcomes in patients.37, 38 In addition, MASCs with ETV6–X gene fusion and other atypical fusion transcripts often demonstrate abundant fibrosclerotic stroma and particularly prominent thick hyalinized fibrous septa. The neoplastic cells may be embedded in a completely hyalinized central part of the tumor (Figure 1c).

Currently, molecular confirmation is considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of MASC.

Clinical Features and Prognosis

MASC is usually encountered in adults (mean, 47 years; range, 14–78 years), with a slight male predominance.6, 11, 13, 20, 26, 27, 28, 29 Most published cases involved the parotid gland, followed by the oral cavity (23%), submandibular gland (8%), with two cases in the accessory parotid gland (2%). Interestingly, primary MASCs of thyroid gland have been recently reported in patients with no history of radiation exposure.46, 47 More importantly, two of these thyroid MASCs showed a minor component of well-differentiated thyroid papillary carcinoma component. FISH was performed revealing ETV6 rearrangement in both components, hence supporting common follicular cell origin of primary thyroid MASC.46

MASC usually behaves indolently, but like other low-grade salivary gland carcinomas, there is some capacity for aggressive behavior including locoregional recurrence and distant metastasis. Particularly important is the rare occurrence of HG transformation that may result in tumor-related death.34, 35, 36

The treatment of MASC has been variable, ranging from simple excision to radical resections, neck dissections, adjuvant radiotherapy and/or adjuvant systemic chemotherapy.6, 28, 29, 30 Recognizing MASC and testing for ETV6 rearrangement may be of potential value in patient treatment, because the presence of the ETV6-NTRK3 translocation may represent a therapeutic target. Recent studies suggested that the inhibition of ETV6-NTRK3 activation could serve as a target for the treatment of patients with this fusion at other sites48, 49 and MASC as well.50

Differential Diagnosis

The major differential diagnostic consideration is AciCC. The neoplastic cells of MASC resemble intercalated duct cells, and they have low-grade nuclei with distinctive nuclear membranes and centrally located nucleoli. The architectural patterns of MASC (ie, microcystic, papillary-cystic, follicular and solid) overlap with those of AciCC. However, the large serous acinar cells with cytoplasmic PAS-positive zymogen-like granules typical of AciCC are completely absent in MASC.6 In difficult cases, immunohistochemistry can aid in the distinction. MASC is consistently positive for S100 and mammaglobin, whereas AciCC is not.6, 13, 14, 21, 22, 28 In contrast, AciCC is typically positive for DOG1 whereas MASC is usually negative.25

Low-grade SDC (intraductal carcinoma) is characterized by a prominent cystic tumor component associated with proliferation of bland eosinophilic ductal cells, frequent intraluminal secretions, and S100 protein and mammaglobin immunoexpression, the features that overlap with MASC.21, 28, 32 In contrast to MASC, however, the epithelial structures of low-grade SDC are characteristically surrounded by an intact layer of p63-positive myoepithelial cells. Rarely, this pattern may be mimicked by MASC displaying a focal intraductal (in situ) component, but with only a very limited number of abluminal p63-positive cells.

Low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma is another potential consideration in the differential diagnosis of MASC because both tumors can have a prominent cystic component with cytologically bland cells that can be eosinophilic, clear or vacuolated. Focal mucicarmine staining in a MASC can cause confusion.13 In contrast to MASC, mucoepidermoid carcinoma is consistently positive for p63 in the epidermoid foci and is usually negative for S100 and mammaglobin. Finally, most cases of low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma harbor a different chromosomal translocation, t(11;19), resulting in CRTC1–MAML2 fusion.51, 52

Other diagnostic considerations could include occasional cases of PLGA, low-grade adenocarcinoma or cystadenocarcinoma NOS, and cystadenoma NOS.53 PLGA could be a consideration primarily because of its bland cytologic features and the fact that it is S100 positive and sometimes mammaglobin positive, but the differences are usually obvious morphologically.21, 22

Summary

MASC is a recently described salivary gland neoplasm defined by its close resemblance to secretory breast carcinoma, particularly at the genetic level where both tumors characteristically harbor the balanced translocation t(12;15) (p13;q25) resulting in the ETV6–NTRK3 fusion gene. It is likely that MASC is more common and more variable in morphology and clinical behavior than originally considered. Recognizing MASC and testing for ETV6 rearrangement is not only useful differential diagnostic tool but may be of potential value in patient treatment, because the presence of the ETV6–NTRK3 fusion transcript may represent a therapeutic target in MASC.

Sclerosing polycystic adenoma

Introduction

Sclerosing polycystic adenoma (SPA) is a rare sclerosing tumor of salivary glands with a characteristic combination of histological features, somewhat reminiscent of fibrocystic changes, sclerosing adenosis and adenosis tumor of the breast. Both have cystic components with a prominent multilobular arrangement, often with small, proliferating, closely packed ductal structures, surrounded by a peripheral myoepithelial layer and stromal fibrosis with focal inflammatory infiltrates. SPA was first described by Smith et al54 under the designation 'sclerosing polycystic adenosis', in a series of nine cases. Since this seminal paper, several small series and case reports have been published55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78 with the largest series of 16 cases published by Gnepp et al.59 Overall, fewer than 100 cases of SPA have been reported so far.

This rare salivary gland lesion was initially believed to be reactive/inflammatory in nature,54, 56 but later we have shown, using HUMARA-based analysis, that SPA is a clonal process.60 Moreover, SPA frequently harbors intraductal epithelial dysplastic proliferations ranging from mild dysplasia to severe dysplasia/carcinoma in situ.56, 58, 59, 60, 63, 67, 69 In addition, cases with extensive in situ component giving impression of intralesional invasive adenocarcinoma70 and frankly malignant invasive carcinoma ex SPA79 were recently reported. Therefore, based on all these newly recognized findings, we suggest to coin the name 'sclerosing polycystic adenoma' (SPA).

Epidemiology and Clinical Findings

Patients range in age from 9 to 84 years with a slight female predominance; the mean age at presentation is around 40 years.80 Most tumors involve the major salivary glands, in particular the parotid gland and less commonly, the submandibular gland.76 Only rare definite cases have been reported in the minor salivary glands of the oral cavity,59, 64, 65, 68 sinonasal tract75 and in the lacrimal gland.77 Other authors have also reported SPA arising from minor salivary glands, but based on the description and microphotographs, some of them may well not represent examples of genuine SPA.65, 81, 82 SPA is most commonly seen as a single lesion, but rare cases with multifocality have been documented.59, 70, 78 A unique report of two cases of SPA in a familial setting in two sisters aged 7 and 33 has been reported recently.78 The younger patient suffered multiple recurrences.78 Symptoms of SPA are nonspecific, the patients typically present with a slow growing painless mass with occasional mild pain or tenderness.

Cytopathologic Features

Very few cases of SPA have undergone fine-needle cytology; three cases in the Gnepp et al59 multi-institutional series, plus one case each described by Imamura et al,58 Kloppenborg et al,61 Etit et al62 and Gupta et al.66 All the reports dealing with cytopathological features of SPA described the presence of syncytial epithelial duct cells with apocrine changes, foamy histiocytes, oncocytes and a cystic-type background with proteinacenous material.58, 61, 62, 67 Fulciniti et al67 have emphasized the combination of different cell types in a single sheet, including small ductal, apocrine and sebaceous-like cells with finely vacuolated cytoplasm as key cytological diagnostic features of SPA. In addition, less common cytological features were represented by sparse lymphoid elements and acinar epithelial cells with coarse cytoplasmic eosinophilic granules;67 these cells had round to oval nuclei with even chromatin and indistinct nucleoli. Other reported findings include flat sheets of cells having a 'squamoid' appearance, cells forming glandular structures, markedly vacuolated cells 'reminiscent of sebaceous differentiation', and cells featuring apical cytoplasmic snouts.80

Histological Features

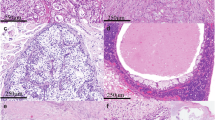

SPAs are well-circumscribed tumors with multiple, densely sclerotic, irregularly defined lobules composed of abundant hyalinized collagen surrounding variably sized collections of ducts with varying degrees of cystic change (Figure 4a). The lesions are frequently unencapsulated, but may have a more or less complete pseudocapsule. The key histological features of SPA include lobular proliferation of ductal and acinar cells, the latter often containing large eosinophilic cytoplasmic zymogen-like granules (PAS-positive, diastase resistant). Not uncommonly, these granules may reach such a size so as to appear as intracytoplasmic globules (Figure 4b). The ductal cells show variable cytomorphological characteristics, including foamy, vacuolated, apocrine, mucous, clear, squamous, columnar and oncocyte-like cells (Figures 4c and d). In addition, the focal presence of true acini composed of distinctly serous cells, juxtaposed to the more commonly occurring and characteristic eosinophilic, granulated acinar cells can be occasionally observed. In most cases, a variably prominent, cystic component is present. The cysts may be lined by flattened, apocrine or vacuolated cells (Figure 5a). Partly, the epithelial cells lining the cysts may be denuded and replaced by foamy macrophages (Figure 5b). Most commonly, the cellular components in SPA are embedded in a sharply delineated, dense, sclerotic collagenous stroma. The stroma may on occasion form hyalinized hypocellular nodules/plaque-like structures that may or may not contain residual epithelial cellular remnants and/or vacuolated foam cell-type macrophages. In addition, the stroma may also display a distinctly myxoid or even myxochondroid quality (Figure 5c). Commonly, the stroma harbors a variably intense, frequently nodular chronic inflammatory infiltrate. The acinar component may or may not show preservation of the lobular architecture. In the latter case, a sclerosing adenosis-like histopathological pattern is encountered and when this is associated with a stroma-induced distortion of the acini/ductules, the process may acquire an infiltrative appearance. Moreover, as described in a few cases by Gnepp et al,59 stromal distortion may lead to the formation of radial scar-like structures. In addition, cases of SPA with dysplastic epithelial changes have been reported, and this may be severe enough to resemble low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) of the breast56, 57, 59, 67, 70 (Figures 6a and c).

Sclerosing polycystic adenoma (SPA). (a) SPAs are well-circumscribed tumors with multiple, densely sclerotic, irregularly defined lobules composed of abundant hyalinized collagen surrounding variably sized collections of ducts with varying degrees of cystic change. (b) The hallmark of SPA are acinar cells with coarse cytoplasmic eosinophilic granules. The ductal cells show variable cytomorphological characteristics, including foamy, vacuolated (c), apocrine, mucous, clear, squamous, columnar and oncocyte-like cells (d).

Sclerosing polycystic adenoma (SPA). (a-c) The cysts may be lined by flattened, apocrine or vacuolated cells (a). Partly, the epithelial cells lining the cysts may be denuded and replaced by foamy macrophages (b). In addition, the stroma may also display a distinctly myxoid or even myxochondroid quality (c).

Sclerosing polycystic adenoma (SPA). (a-c) The tumor is composed of proliferating solid and tubular ductal structures separated by abundant fibrous stroma (a). Area with mild to moderate dysplastic epithelial changes with cribriform growth pattern consistent with ductal carcinoma in situ (b). More cellular foci with solid and tubular growth pattern within hyalinized sclerotic stroma are seen (c).

Immunohistochemical Findings

Immunohistochemistry demonstrates preservation of the lobular architecture with staining of intact peripheral myoepithelial cell layer surrounding the ductal and acinar structures, including those with dysplastic and in situ ductal lesions (Figures 7a and c). The proliferative activity is low with MIB1 index 1–2% in both ductal and acinar structures, but is substantially increased in dysplastic intraductal epithelium and in DCIS lesions.70

Sclerosing polycystic adenoma (SPA): immunoprofile. (a-d) Immunohistochemistry demonstrates preservation of the lobular architecture with staining of intact peripheral myoepithelial cell layer surrounding the ductal and acinar structures, including those with dysplastic and in situ ductal lesions (a), calponin (b) and GFAP (c). Dysplastic ductal epithelium often demonstrates androgen receptors (d).

Immunohistochemistry shows that the ductal and acinar cells are positive for cytokeratin (AE1/AE3 and CAM5.2), variably positive for EMA, S100 protein, antimitochondrial antibody, but negative for CEA, p53 and HER-2/neu. The acinar cells with coarse granules react with GCDFP-15. Androgen, progesterone and estrogen receptors may be detected in 20%, 10% and 5% of ductal cells, respectively (Figure 7d). Ducts filled with hyperplastic and dysplastic epithelium are surrounded by an intact myoepithelial layer, positive for smooth muscle actin, p63 and calponin.

Molecular Findings

PCR-based analysis of patterns of X-chromosome inactivation was performed using a HUMARA in six cases of SPA with focal dysplastic epithelial structures. We were able to establish clonality (non-random pattern of inactivation of X-chromosome) in all analyzable (female) cases.60

Differential Diagnosis

SPA is a very rare tumor of salivary glands and most histopathologists are not familiar with this lesion, and thus it can be mistaken for other benign and even malignant entities, most often tumors such as pleomorphic adenoma, mucoepidermoid and AciCCs and, cystadenocarcinoma. Nevertheless, the histological features of SPA are very characteristic and awareness of these allows for a diagnosis of this lesion based on hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections alone. Other differential diagnostic considerations include polycystic (dysgenetic) disease and sclerotic sialadenitis, as well as SDC, (including the so-called low-grade variant) and adenocarcinoma, NOS. Major microscopic clues to a correct diagnosis include maintenance of the lobular architecture, ductal ectasia, scar-like hyalinised fibrous sclerosis, and a spectrum of foam, apocrine, granular and mucous cells, in addition to the presence of tubuloacinar structures composed of large acinar cells with prominent brightly eosinophilic granules. In contrast, intraductal hyperplasia, particularly if associated with dysplasia, may lead one to suspect a neoplastic process, but clues to the benign nature of SPA are that it is well-circumscribed, lacks an invasive growth pattern, and that mitotic/proliferative activity is low.

The characteristic lobular growth pattern and large Paneth cell-like acinar cells of SPA are not seen in pleomorphic adenoma, whereas SPA lacks a prominent myoepithelial cell component and chondromyxoid stroma typical of PA. Chronic sclerosing sialadenitis lacks a nodular pattern and typical structural heterogeneity of SPA, although both lesions share prominent fibrosis. Moreover, large acinic cells with coarse PAS-positive zymogen-like cytoplasmic granules are not seen in chronic sclerosing sialadenitis.

Both AciCC and mucoepidermoid carcinomas can be well circumscribed, and cells with small PASD-positive cytoplasmic granules are characteristic of the former. However, in our experience, the granules of AciCC are never as large as those seen in SPA, and furthermore AciCC never has the varied architecture and cell population of SPA. Mucous cells are largely absent from SPA, whereas they are almost always numerous in mucoepidermoid carcinoma, particularly the low-grade well-circumscribed examples. Furthermore, the myoepithelial cell mantle surrounding the cysts, ducts and acini of SPA is not seen in AciCC or mucoepidemoid carcinoma.

Summary

SPA is a rare sclerosing tumor of salivary glands characterized by combination of cystic ductal structures with variable cell lining including vacuolated, apocrine, mucinous, squamous and foamy cells, by prominent large acinar cells with coarse eosinophilic cytoplasmic zymogen-like granules, and closely packed ductal structures, surrounded by a peripheral myoepithelial layer and stromal fibrosis with focal inflammatory infiltrates. SPA frequently harbors intraductal epithelial dysplastic proliferations ranging from mild dysplasia to severe dysplasia/carcinoma in situ. Moreover, SPA has been proven to be clonal process by HUMARA assay and is associated with considerable rate of recurrences. Therefore, based on all these newly recognized findings, we believe that SPA is likely a neoplasm, and we suggest to coin the name 'sclerosing polycystic adenoma'.

Cribriform adenocarcinoma of minor salivary glands

Introduction

Cribriform adenocarcinoma of minor salivary glands (CAMSGs) is a tumor originally described in 1999 by Michal et al83 under the name cribriform adenocarcinoma of the tongue. In the original series, all eight neoplasms were located in the tongue; and their morphology was similar to papillary carcinoma of the thyroid gland resulting in the presumption that cribriform adenocarcinoma may have an origin in the lingual thyroglossal duct anlage.83 After the original paper was published, we started to receive identical tumors located outside the tongue, including the soft palate, retromolar buccal mucosa and the lip, which seriously questioned the theory of the origin in the lingual thyroglossal duct anlage. These new findings were summarized in a recent paper published by our group, and cribriform adenocarcinoma of the tongue was renamed as CAMSGs.84

According to the last WHO Classification of Tumours of the Head and Neck of 2005, CAMSG is a provisional entity without a clear statement whether it represents a genuine entity or is merely a variant of PLGA.85 Nevertheless, we believe, as well as some other authors,86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92 that CAMSG is a distinct neoplasm that should be classified separately from PLGA.

Histopathological Features

Grossly, the tumors are unencapsulated, white to gray in color, and hard in consistency, usually with no areas of necroses and hemorrhages, covered by nonulcerated intact epithelium (Figure 8a).

Cribriform adenocarcinoma of minor salivary glands (CAMSGs). CAMSG is composed predominantly of cribriform, solid and glomeruloid structures. The tumor is covered by intact mucosal epithelium (a) and lymphovascular invasion is often observed (b). The histological structure of CAMSG is quite characteristic with cribriform, tubular, glomeruloid or solid areas separated by fibrous tissue (c). In solid areas, the tumor nests are frequently detached from the surrounding fibrous stroma by clefts and often contains central necrosis (d). Characteristic feature seen in more than one-third of CAMSGs is presence of mucinous stroma composed of mucinous matrix and rare spindle cell myofibroblasts (e). Overlapping clear 'Orphan Annie eye-like nuclei' of CAMSG are remarkably similar to those of papillary thyroid carcinoma (f).

Histologically, the tumors have invasive margins and in most cases they infiltrate the muscular layer of the tongue and/or adjacent tissues. Lymphovascular invasion is observed in a third of cases (Figure 8b). The tumors are composed predominantly of cribriform (Figure 8c) to microcribriform and solid structures (Figure 8d) in variable proportions. Rare tumors may have an overtly cystic configuration. In most instances, the tumor architecture consists mainly of a solid mass divided by fibrous septa into irregularly shaped and sized nodules composed of centrally necrotic areas. In the solid areas, the tumor nests are frequently detached from the surrounding fibrous stroma by clefts (Figure 8d). The peripheral layer of such solid tumor nests often displays hyperchromatic nuclei in a somewhat palisaded pattern. In rare cases, psammoma bodies are found. Another characteristic feature seen in most cases is presence of mucinous spindle cell myofibroblastic stromal septa, composed of mucinous matrix and rare spindle cell myofibroblasts, seen mostly in early infiltrative foci (Figure 8e). The most prominent feature of the tumors, however, is the appearance of the nuclei. These often overlap one with another, and are pale, optically clear and vesicular with a ground glass appearance. Rarely, there are solid areas composed of these cells with optically clear nuclei. Cellular atypia is mild, and mitotic figures are in most cases rare. Generally, there are one to three small inconspicuous nucleoli. The cytoplasm is clear to eosinophilic. Cytologically, all tumors are composed of one cell type. The overall morphology of the tumor, particularly with focal papillary growth and with overlapping clear 'Orphan Annie eye-like nuclei', is remarkably similar to various variants of papillary thyroid carcinoma (Figure 8f). The cervical lymph node metastases have usually identical appearances to the primary tumors.

Clinical Findings

Two-thirds of tumors, published in the literature so far, were located in the tongue (usually the base of the tongue), and the rests of the tumors were in the soft palate, retromolar buccal mucosa, lingual tonsils, upper lip, floor of the mouth and epiglottis.84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 93, 94, 95, 96 One tumor located in the tongue was described to have a pedunculated configuration.86 Women and men are approximately equally affected. The neck lymph node metastases are often present in the lateral neck at the time of diagnosis, less commonly the cervical lymph node metastases are bilateral. The tumors were treated by surgical excision often accompanied by neck lymph node dissection. Approximately half of the patients received radiotherapy. All patients with available follow-up were alive and without signs of metastases.84, 86, 87, 88, 89, 93, 94, 95

Immunohistochemical Findings

CAMSGs react strongly with antibodies to AE1-3, CAM5.2, CK7, CK8, CK18, S100 protein, SOX10 (Figure 9a), calponin and vimentin. Smooth muscle actin reacts often in a patchy manner (Figure 9b). In addition, a significant positivity for c-kit (CD117) in 10–80% cells with a strong cytoplasmic and membranous expression has been reported.84 Immunostaining for cyclin D1 and p53 protein demonstrate variable percentages of positive nuclei ranging between 0–35% (mean 15%) and 0–10% (mean 2,6%), respectively.84 Basal and myoepithelial cell markers, such as p63, calponin, CK14 and CK5/6, are positive in all tumors with variable proportions up to 60% often at the periphery of the tumor nodules, especially marking the palisaded cells surrounding the glomeruloid structures. Expression of CK19 was variable with mild to moderate staining of membranes and cytoplasm in 12 out of 17 cases in two studies.84, 89 EMA, EGFR, HER-2/neu, ER and PR are usually negative. More importantly, all the tumors are invariably completely devoid of any staining for TTF-1 and thyroglobulin. The Ki-67 proliferation index is <25%.84, 89

Ultrastructure

Ultrastructurally, all the cells of the tumor are uniform and are thus of one cell type. They have irregularly clefted nuclei with nucleoli. The cytoplasm contains few organelles, including small numbers of mitochondria, lysosomes and Golgi apparatus. Rare cells contain stacks of confronting cisternae of rough endoplasmic reticulum. The cells are attached one to each other by well-formed desmosomes. Interestingly, at the ultrastructural level, even the areas with a solid appearance at the light microscopical level reveal a microcribriform arrangement. The secretory spaces are composed of well-formed microvilli on the apical borders of the cells. A further unusual feature is that many of the secretory cells displaying the apical microvilli also contain groups of microfilaments in the cytoplasm. These cells thus had features of hybrid myoepithelial-secretory cells, and had thus all aspects of 'secretory myoepithelia'. Many cells, especially those in areas, which showed spindling of neoplastic cells, are found to contain numerous bundles of cytoplasmic tonofilaments (Figure 10). Presence of secretory myoepithelial cells in CAMSG seems to be almost unique83, 84 with exception of very rare mucinous myoepithelial tumors that may contain abundant intracellular mucin.92

Molecular Findings

No somatic mutations of BRAF, K-RAS, H-RAS, N-RAS, c-kit and PDGFRa genes were found in any of the analyzable cases in two papers.82, 87 However, in RET proto-oncogene, heterozygous polymorphism Gly691Ser in exon 11 (one case), heterozygous polymorphism p.Leu769Leu in exon 13 (one case), heterozygous polymorphism Ser904Ser in exon 15 (one case) and intronic variant p.IVS14-24 G/A of exon 14 (two cases) were found in one study.89 Weinreb et al97 recently identified a novel and recurrent gene rearrangement in PRKD1-3 in CAMSG, suggesting possible pathogenetic dichotomy from PLGA.

Differential Diagnosis

The most important differential diagnosis of CAMSG is PLGA. In several recent studies, the authors have argued that there is a significant proportion (about 35%) of the tumors on the PLGA spectrum exhibiting mixed morphology between PLGA and CAMSG.97, 98, 99 Although CAMSG and PLGA may show morphologic overlap, and both tumor entities have molecular alterations affecting the same gene locus PRKD1/2/3, there are significant differences. Although mutations in PRKD genes100 including novel PRDK1 hotspot somatic mutation encoding p.Glu710Asp were reported in classic PLGA,101 most cases of CAMSGs harbor PRKD1/2/3 translocations.97 Moreover, there are significant differences between CAMSG and PLGA both in morphology and clinical behavior.

PLGA typically has a wide range of architectural appearances, including tubule and fascicle formation, as well as solid, cribriform and sometimes small papillary structures. A particularly characteristic feature of PLGA is the occurrence of streaming columns of single file or narrow trabeculae of cells forming concentric whorls, thereby creating a target-like appearance.85 Perineural invasion is often seen, but does not indicate more aggressive behavior. At the cellular level, PLGA quite often contains clear cells and less frequently, mucous cells. In 3–5% of cases of PLGA, crystals resembling the tyrosine-rich crystals of some pleomorphic adenomas can be found.102, 103 None of these features were ever described in CAMSG.

Myxoid stromal areas represented by mucinous spindle cell myofibroblastic stromal septa seen in a third of the cases of CAMSG may resemble stroma in the pleomorphic adenomas.104 These myxoid myofibroblastic stromal septa in CAMSG, however, never produce true cartilage and its typical glassy appearance and its association with epithelial component at the advancing edges of the tumors is different from mesenchymal-like differentiation in pleomorphic adenomas.

The most striking feature of CAMSG is a nuclear similarity to papillary carcinoma of the thyroid gland, and this is not seen to any great extent in PLGA. Further, PLGA only rarely metastasizes, and it is our view that a good proportion of the putative examples of metastasizing PLGA could probably represent CAMSG, which had been included in some published series of PLGA. The literature records several possible examples of CAMSG published as PLGA or under other names. Perez-Ordonez et al105 described 17 PLGAs among which there were two examples of 'PLGA' of the tongue. In this series, there was a much higher metastatic rate than is usual for PLGA, as 5 of the 17 cases had secondaries in the neck lymph nodes. Two of these five cases had a papillary appearance, and Figures 4a and b of this paper show a tumor with an appearance identical to that of CAMSG.105 Another possible candidate of CAMSG was reported by Colmenero et al.106 In a series of 14 PLGAs, one tumor involved the base of the tongue and metastasized to the neck lymph nodes. Their Figure 2 (and possibly also Figure 3) shows a tumor very similar to CAMSG. Two other possible candidates for CAMSG were published under different names, and both carcinomas metastasized to the cervical lymph nodes.107, 108 Yajima et al. reported a tumor of the tongue in a 59-year-old man, which was called 'tubular adenocarcinoma',108 and Crocker et al. described a 5-year-old boy with an adenocarcinoma, which the authors designated 'papillary adenocarcinoma of minor salivary gland'.109 Particularly reminiscent are the pallor and ground glass quality of the nuclei as seen in both tumors, the solid and cribriform arrangement in the first tumor108 and the papillary appearance resulting from tumor cell detachment from the stroma as seen in the other report.109 As a consequence, therefore, we strongly suspect that if cases of CAMSG were excluded, then the metastatic rate of true PLGA would be exceptional. In contrast, the patients with CAMSG had lymph node metastases in 19/31 cases already at the time of the presentation of the primary tumor in the published series.84

Another important differential diagnosis, especially in cases where the primary tumor is occult and excision of a metastatic focus in lateral neck lymph node is the first biopsy obtained from a patient, is a metastasis of a papillary carcinoma of thyroid gland. One illustrative case was described by Laco et al.89 In their case 4, the original CAMSG located in the mouth floor was misdiagnosed as 'proliferating pleomorphic adenoma' and no further treatment was judged necessary. The lymph node lesion, which developed 37 months after removal of the primary tumor was misdiagnosed as a metastasis of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Total thyreoidectomy was performed but no tumor was found. Subsequently, the lymph node was sent for second opinion, and diagnosis of metastasizing CAMSG was established. All the tissue samples resected from the nasopharynx, base of tongue and palatine tonsils were negative. Therefore, the original tumor in the mouth floor was sent for second opinion and diagnosed as CAMSG. Thus, the correct diagnosis of the primary tumor took 45 months and misdiagnosis of CAMSG as a metastatic thyroid papillary carcinoma led to unnecessary thyroidectomy.89 CAMSG usually reveals a solid growth devoid of colloid and eosinophilic material present in follicular areas is rather pale in contrast to metastatic foci seen papillary thyroid carcinoma showing typical deeply eosinophilic colloid with 'moth-eaten peripheries' and frequent cystic configuration. In addition, giant multinucleated cells are not observed in CAMSG and psammoma bodies are found only exceptionally. Unlike papillary thyroid carcinoma, the CAMSG is composed of hybrid secretory myoepithelial cells. Most importantly, CAMSG is consistently negative with both thyroglobulin and TTF-1.83, 89, 89 However, one must be alerted to the fact that both CAMSG and papillary thyroid carcinoma may show variable expression of galectin-3, CK19 and HBME-1.89

Summary

In conclusion, we are convinced that CAMSG is a distinct tumor entity that differs from PLGA by location (ie, most often arising on the tongue), nuclear features, histological structure, molecular alterations, and clinical behavior with frequent metastases at the time of presentation of the primary tumor. Early metastatic disease seen in most cases of CAMSG associated with indolent behavior makes it a unique neoplasm among all low-grade salivary gland tumors.

References

McCord C, Weinreb I, Perez-Ordonez B . Progress in salivary gland pathology: new entities and selected molecular features. Diagn Histopathol 2012; 18: 253–260.

Skalova A, Vanecek T, Simpson RHW et al, Molecular advances in salivary gland pathology and their practical application. Diagn Histopathol 2012; 18: 388–396.

Weinreb I . Translocation-associated salivary gland tumors: a review and update. Adv Anat Pathol 2013; 20: 367–376.

Simpson RHW, Skálová A, Di Palma S et al, Recent advances in the diagnostic pathology of salivaryglands. Virchows Arch 2014; 465: 371–384.

Garcia JJ, Oloviera AM . Fusion transcripts that characterize malignancies of salivary gland origin. Pathol Case Reviews 2015; 20: 22–26.

Skalova A, Vanecek T, Sima R et al, Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands, containing the ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene: a hitherto undescribed salivary gland tumor entity. Am J Surg Pathol 2010; 34: 599–608.

Tognon C, Knezevich SR, Huntsman D et al, Expression of the ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion as a primary event in human secretory breast carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2002; 2: 367–376.

McDivitt RW, Stewart FW . Breast carcinoma in children. JAMA 1966; 195: 144–146.

Rosen PP, Cranor ML . Secretory carcinoma of the breast. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1991; 115: 141–144.

Li Z, Tognon CE, Godinho FJ et al, ETV6-NTRK3 fusion oncogene initiates breast cancer from committed mammary progenitors via activation of AP1 complex. Cancer Cell 2007; 12: 542–558.

Griffith C, Seethala R, Chiosea SI . Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma: a new twist to the diagnostic dilemma of zymogen granule poor acinic cell carcinoma. Virchows Archiv 2011; 459: 117–118.

Fehr A, Loning T, Stenman G . Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of the salivary glands with ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion. Letter to the Editor. Am J Surg Pathol 2011; 35: 1600–1602.

Connor A, Perez-Ordoñez B, Shago M et al, Mammary analog secretory carcinoma of salivary gland origin with the ETV6 gene rearrangement by FISH: expanded morphologic and immunohistochemical spectrum of a recently described entity. Am J Surg Pathol 2012; 36: 27–34.

Chiosea SI, Griffith C, Assad A et al, The profile of acinic cell carcinoma after recognition of mammary analog secretory carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2012; 36: 343–350.

Bishop JA, Yonescu R, Batista DA et al, Cytopathologic features of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma. Cancer Cytopathol 2013; 121: 228–233.

Levine P, Fried K, Krevitt LD et al, Aspiration biopsy of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of accessory parotid gland: another diagnostic dilemma in matrix-containing tumors of the salivary glands. Diagn Cytopathol 2014; 42: 49–53.

Griffith CC, Stelow EB, Saqi A et al. The cytological features of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma: a series of 6 molecularly confirmed cases. Cancer Cytopathol 2013; 121: 234–241.

Jung MJ, Kim SY, Nam SY et al, Aspiration cytology of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of the salivary gland. Diagn Cytopathol 2015; 43: 287–293.

Samulski TD, LiVolsi VA, Baloch Z . The cytopathologic features of mammary analog secretory carcinoma and its mimics. Cytojournal 2014; 11: 24.

Chiosea SI, Griffith C, Assad A et al, Clinicopathological characterization of mammary analogue carcinoma of salivary glands. Histopathology 2012; 61: 387–394.

Bishop JA, Yonescu R, Batista D et al, Utility of mammaglobin immunohistochemistry as a proxy marker for the ETV6-NTRK3 translocation in the diagnosis of salivary mammary analogue secretory carcinoma. Hum Pathol 2013; 44: 1982–1988.

Patel KR, Solomon IH, El-Mofty SK et al, Mammaglobin and S-100 immunoreactivity in salivary carcinomas other than mammary analogue secretory carcinoma. Hum Pathol 2013; 44: 2501–2508.

Skálová A . Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary gland origin: an update and expanded morphologic and immunohistochemical spectrum of recently described entity. Head Neck Pathol 2013; 7 (suppl 1): S30–S36.

Laco J, Švajdler M Jr, Andrejs J et al, Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands: a report of 2 cases with expression of basal/myoepithelial markers (calponin, CD10 and p63 protein). Pathol Res Pract 2013; 209: 167–172.

Chenevert J, Duvvuri U, Chiosea S et al, DOG1: a novel marker of salivary acinar and intercalated duct differentiation. Mod Pathol 2012; 25: 919–929.

Urano M, Nagao T, Miyabe S et al, Characterization of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary gland: discrimination from its mimics by the presence of the ETV6-NTRK3 translocation and novel surrogate marker. Hum Pathol 2015; 46: 94–103.

Majewska H, Skálová A, Stodulski D et al, Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands: first retrospective study of a new entity in Poland with special reference to ETV6 gene rearrangement. Virchows Arch 2015; 466: 245–254.

Pinto A, Nosé V, Rojas C et al, Searching for mammary analogue secretory carcinoma among their mimicks. Mod Pathol 2014; 27: 30–37.

Bishop JA, Yonescu R, Batista D et al, Most nonparotid “acinic cell carcinomas” represent mammaryanalog secretory carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol 2013; 37: 1053–1057.

Bishop JA . Unmasking MASC: bringing to light the unique morphologic, immunohistochemical and genetic features of the newly recognized mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands. Head Neck Pathol 2013; 7: 35–39.

Shah AA, Wenig BM, LeGallo RD et al, Morphology in conjunction with immunohistochemistry is sufficient for the diagnosis of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol 2015; 9: 85–95.

Stevens TM, Kovalovsky AO, Velosa C et al, Mammary analog secretory carcinoma, low-grade salivary duct carcinoma, and mimickers: a comparative study. Mod Pathol 2015; 28: 1084–1100.

Hsieh MS, Jeng YM, Jhuang YL et al, Carbonic anhydrase VI: a novel marker for salivary serous acinar differentiation and its implication to discriminate acinic cell carcinoma from mammary analogue secretory of the salivary gland. Histopathology 2016; 68: 641–647.

Skálová A, Vanecek T, Majewska H et al, Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands with high-grade transformation: report of 3 cases with the ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion and analysis of TP53, beta-catenin, EGFR, and CCND1 genes. Am J Surg Pathol 2014; 38: 23–33.

Luo W, Lindley SW, Lindley PH et al, Mammary analog secretory carcinoma of salivary gland with high-grade histology arising in palate, report of a case and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2014; 7: 9008–9022.

Jung MJ, Song JS, Kim SY et al, Finding and characterizing mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of the salivary gland. Korean J Pathol 2013; 47: 36–43.

Ito Y, Ishibashi K, Masaki A et al, Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands: a clinicopathological and molecular study including 2 cases harboring ETV6-X fusion. Am J Surg Pathol 2015; 39: 602–610.

Skalova A, Vanecek T, Simpson RHW et al, Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands. Molecular analysis of 25 ETV6 gene rearranged tumors with lack of detection of classical ETV6-NTRK3 fusion transcript by standard RT-PCR: report of 4 cases harboring ETV6-X gene fusion. Am J Surg Pathol 2016; 40: 3–13.

Knezevich SR, McFadden DE, Tao W et al, A novel ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion in congenital fibrosarcoma. Nat Genet 1998; 18: 184–187.

Bourgeois JM, Knezevich SR, Mathers JA et al, Molecular detection of the ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion differentiates congenital fibrosarcoma from other childhood spindle cell tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 2000; 24: 937–946.

Rubin BP, Chen CJ, Morgan TW et al, Congenital mesoblastic nephroma t(12;15) is associated with ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion: cytogenetic and molecular relationship to congenital (infantile) fibrosarcoma. Am J Pathol 1998; 153: 1451–1458.

Knezevich SR, Garnett MJ, Pysher TJ et al, ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusions and trisomy 11 establish a histogenetic link between mesoblastic nephroma and congenital fibrosarcoma. Cancer Res 1998; 15: 5046–5048.

Kralik JM, Kranewitter W, Boesmueller H et al, Characterization of a newly identified ETV6-NTRK3 fusion transcript in acute myeloid leukemia. Diagn Pathol 2011; 6: 19.

Alassiri AH, Ali RH, Shen Y et al, ETV6-NTRK3 is expressed in a subset of ALK-negative inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Am J Surg Pathol 2016; 40: 1051–1061.

Leeman-Neill RJ, Kelly LM, Liu P et al, ETV6-NTRK3 is a common chromosomal rearrangement in radiation-associated thyroid cancer. Cancer 2014; 120: 799–807.

Dogan S, Wang L, Ptashkin RN et al, Mammary analog secretory carcinoma of the thyroid gland: a primary thyroid adenocarcinoma harboring ETV6-NTRK3 fusion. Mod Pathol 2016; 29: 985–995.

Reynolds S, Shaheen M, Olson G et al, A case of primary mammary analog secretory carcinoma (MASC) of the thyroid masquerading as papillary thyrodid carcinoma: potentially more than a one off. Head Neck Pathol Online publication 2016; 10: 405–413.

Chi HT, Ly BT, Kano Y et al, ETV6-NTRK3 as a therapeutic target of small molecule inhibitor PKC412. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2012; 429: 87–92.

Tognon CE, Somasiri AM, Evdokimova VE et al, ETV6-NTRK3- mediated breast epithelial cell transformation is blocked by targeting the IGF1R signaling pathway. Cancer Res 2011; 71: 1060–1070.

Drilon A, Li G, Dogan S et al, What hides behind the MASC: clinical response and acquired resistance to entrectinib after ETV6-NTRK3 identification in a mammary analogue secretory carcinoma (MASC). Ann Oncol 2016; 27: 920–926.

Tonon G, Modi S, Wu L et al, t(11;19) (q21;p13) translocation in mucoepidermoid carcinoma creates a novel fusion product that disrupts a Notch signaling pathway. Nat Genet 2003; 33: 208–213.

Okumura Y, Miyabe S, Nakayama T et al, Impact of CRTC1/3–MAML2 fusions on histological classification and prognosis of mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Histopathology 2011; 59: 90–97.

Williams L, Chiosea SI . Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma mimicking salivary adenoma. Head Neck Pathol 2013; 7: 316–319.

Smith BC, Ellis GL, Slater LJ et al, Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of major salivary glands: a clinicopathologic analysis of nine cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1996; 20: 161–170.

Donath K, Seifert G . Sclerosing polycystic sialadenopathy. A rare non-tumorous disease. Pathologe 1997; 18: 368–373.

Skalova A, Michal M, Simpson RH et al, Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of parotid gland with dysplasia and ductal carcinoma in situ. Report of three cases with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural examination. Virchows Arch 2002; 440: 29–35.

Mackle T, Mulligan AM, Dervan PA et al, Sclerosing polycystic sialadenopathy: a rare cause of recurrent tumor of the parotid gland. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004; 130: 357–360.

Imamura Y, Morishita T, Kawakami M et al, Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of the left parotid gland: report of a case with fine needle aspiration cytology. Acta Cytol 2004; 48: 569–573.

Gnepp DR, Wang LJ, Brandwein-Gensler M et al, Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of the salivary gland. Am J Surg Pathol 2006; 30: 154–164.

Skálová A, Gnepp DR, Simpson RH et al, Clonal nature of sclerosing polycystic adenosis of salivary glands demonstrated by using the polymorphism of the human androgen receptor (HUMARA) locus as a marker. Am J Surg Pathol 2006; 30: 939–944.

Kloppenborg RP, Sepmeijer JW, Sie-Go DM et al, Sclerosing polycystic adenosis: a case report. B-Ent 2006; 2: 189–192.

Etit D, Pilch BZ, Osgood R et al, Fine-needle aspiration biopsy findings in sclerosing polycystic adenosis of the parotid gland. Diagn Cytopathol 2007; 35: 444–447.

Bharadwaj G, Nawroz I, O’Regan B . Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of the parotid gland. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007; 45: 74–76.

Noonan VL, Kalmar JR, Allen CM et al, Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of minor salivary glands: report of three cases and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007; 104: 516–520.

Meer S, Altini M . Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of the buccal mucosa. Head Neck Pathol 2008; 2: 31–35.

Gupta R, Jain R, Singh S et al, Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of parotid gland: a cytological diagnostic dilemma. Cytopathology 2009; 20: 130–132.

Fulciniti F, Losito NS, Ionna F et al, Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of the parotid gland: report of one case diagnosed by fine-needle cytology with in situ malignant transformation. Diagn Cytopathol 2010; 38: 368–373.

Gurgel CA, Freitas VS, Ramos EA et al, Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of the minor salivary gland: case report. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2010; 76: 272.

Perottino F, Barnoud R, Ambrun A et al, Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of the parotid gland: diagnosis and management. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 2010; 127: 20–22.

Petersson F, Tan PH, Hwang JS . Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of the parotid gland: report of a bifocal, paucicystic variant with ductal carcinoma in situ and pronounced stromal distortion mimicking invasive carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol 2011; 5: 188–192.

Tokyol C, Aktepe F, Hasturk GS et al, Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of the parotid gland presenting with a Warthin tumor. Kulak Burun Bogaz Ihtis Derg 2012; 22: 288–292.

Kim BC, Yang DH, Kim J et al, Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of the parotid gland. J Craniofac Surg 2012; 23: e451–e452.

Eliot CA, Smith AB, Foss RD . Sclerosing polycystic adenosis. Head Neck Pathol 2012; 6: 247–249.

Park IH, Hong SM, Choi H et al, Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of the nasal septum: the risk of misdiagnosis. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol 2013; 6: 107–109.

Su A, Bhuta SM, Berke GS et al, A unique case of sclerosing polycystic adenosis of the sinonasal tract. Hum Pathol 2013; 44: 1937–1940.

Beato Martinez A, Moreno Juara A, Candia Fernandez A . Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of the submandibular gland. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp 2013; 64: 78–80.

Pfeiffer ML, Yin VT, Bell D et al, Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of the lacrimal gland. Ophthalmology 2013; 120: e1.

Manajlovič S, Virag M, Milenovič A et al, Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of parotid gland: a unique report of two cases occurring in two sisters. Path Res Pract 2014; 210: 342–345.

Marques RC, Félix A . Invasive carcinoma arising from sclerosing polycystic adenosis of the salivary gland. Virchows Arch 2014; 464: 621–625.

Petersson F . Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of salivary glands: a review with some emphasis on intraductal epithelial proliferations. Head Neck Pathol 2013; 7 (Suppl 1): S97–106.

Mokhtari S, Moghadam SA, Mirafsharieh A . Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of retromolar pad area: a case report. Case Reports in Pathol 2014; 2014: 982432.

Swelam W . The pathogenic role of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) in sclerosing polycystic adenosis. Pathol Res Pract 2010; 206: 565–571.

Michal M, Skálová A, Simpson RHW et al, Cribriform adenocarcinoma of the tongue: a hitherto unrecognized type of adenocarcinoma characteristically occurring in the tongue. Histopathology 1999; 35: 495–501.

Skalova A, Sima R, Kaspirkova-Nemcova J et al, Cribriform adenocarcinoma of minor salivary gland origin principally affecting the tongue: characterization of new entity. Am J Surg Pathol 2011; 35: 1168–1176.

Luna MA, Wenig BM Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma. In: Barnes EL, Eveson JW, Reichart P et al, (eds). World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours. IARC Press: Lyon, France, 2005, pp 223–224.

Prasad KC, Kaniyur V, Pai RR et al, Pedunculated cribriform adenocarcinoma of the base of the tongue. Ear Nose Throat J 2004; 83: 62–64.

Borowsky-Borowy P, Dyduch G, Papla B et al, Cribriform adenocarcinoma of the tongue. Pol J Pathol 2011; 3: 168–171.

Cocek A, Hronkova K, Voldanova J et al, Cribriform adenocarcinoma of the base of the tongue and low-grade, polymorphic adenocarcinomas of the salivary glands. Oncol Lett 2011; 2: 135–138.

Laco J, Kamaradova K, Vitkova P et al, Cribriform adenocarcinoma of minor salivary glands may express galectin-3, cytokeratin 19, and HMBE-1 and contains polymorphisms of RET and H-RAS proto-oncogenes. Virchows Arch 2012; 461: 531–540.

Luna M . Controversial salivary gland lesions. Pathology 2005; 97: 61–64.

Majewska H, Skalova A, Weinreb I et al, Giant cribriform adenocarcinoma of the tongue showing PRKD3 rearrangement. Pol J Pathol 2016; 67: 84–90.

Gnepp DR . Salivary gland tumor "wishes" to add to the next WHO Tumor Classification: sclerosing polycystic adenosis, mammary analogue secretory carcinoma, cribriform adenocarcinoma of the tongue and other sites, and mucinous variant of myoepithelioma. Head Neck Pathol 2014; 8: 42–49.

Brierley D, Green D, Spedight PM . Cribriform adenocarcinoma of the minor salivary glands arising in the epiglottis-a previously undocumented occurrence. Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2015; 120: e174–e176.

Gailey MP, Bayon R, Robinson RA . Cribriform adenocarcinoma of minor salivary gland: a report of two cases with an emphasis on cytology. Diagn Cytopathol 2014; 42: 1085–1090.

Advenier AS, Poupart M, Devouassoux-Shisheboran M et al, Adenocarcinoma of minor salivary gland origin: a recently described lesion. A case report. Ann Pathol 2013; 33: 398–401.

Obokata A, Sakurai S, Hirato J et al, Cytologic features of low-grade cribriform cystadenocarcinoma of the submandibular gland: a case report. Acta Cytol 2013; 57: 207–212.

Weinreb I, Zhang L, Tirunagari LM et al, Novel PRKD gene rearrangements and variant fusions in cribriform adenocarcinoma of salivary gland origin. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2014; 53: 845–856.

Seethala RR, Johnson JT, Barnes EL et al, Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma: the University of Pittsburgh experience. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010; 136: 385–392.

Xu B, Aneja A, Ghossein R et al, Predictors of outcome in the phenotypic spectrum of polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma (PLGA) and cribriform adenocarcinoma of salivary glands (CASG). A retrospective study of 69 patients. Am J Surg Pathol 2016, in press.

Piscuglio S, Fusco N, Ng CK et al, Lack of PRKD2 and PRKD3 kinase domain somatic mutations in PRKD1 wild-type classic polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinomas of the salivary gland. Histopathology 2016; 68: 1055–1062.

Weinreb I, Piscuglio S, Martelotto LG et al, Hotspot activating PRKD1 somatic mutations in polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinomas of the salivary glans. Nat Genet 2014; 46: 1166–1169.

Raubenheimer EJ, Van Heerden WFP, Thein T . Tyrosine-rich crystalloids in a polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1990; 70: 480–482.

Cleveland DB, Cosgrove MM, Martin SE . Tyrosine-rich crystalloids in a fine needle aspirate of a polymorphous low grade adenocarcinoma of a minor salivary gland. Acta Cytol 1994; 38: 247–251.

Michal M, Kacerovska D, Kazakov DV . Cribriform adenocarcinoma of the tongue and minor salivary glands: A review. Head Neck Pathol 2013; 7: S3–S11.

Perez-Ordonez B, Linkov I, Huvos AG . Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma of minor salivary glands: a study of 17 cases with emphasis on cell differentiation. Histopathology 1998; 32: 521–529.

Colmenero CM, Patron M, Burgueno M et al, Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma of the oral cavity. A report of 14 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1982; 50: 595–600.

Seifert G, Sobin LH . Histological Classification of Salivary Gland Tumours, 2nd ed. Springer-Verlag: Berlin, 1991.

Yajima M, Yamazaki T, Minemura T et al, Tubular adenocarcinoma of the apex of the tongue. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1989; 47: 86–88.

Crocker TP, Kreutner A, Othersen HB et al, Papillary adenocarcinoma of minor salivary gland origin in a child. Arch Otolaryngol 1983; 109: 827–831.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Skalova, A., Michal, M. & Simpson, R. Newly described salivary gland tumors. Mod Pathol 30 (Suppl 1), S27–S43 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.167

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.167

This article is cited by

-

Cribriform adenocarcinoma of the minor salivary glands: a case report

Journal of Medical Case Reports (2023)

-

Prevalence of NTRK Fusions in Canadian Solid Tumour Cancer Patients

Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy (2023)

-

Mammary Analogue Secretory Carcinoma of Parotid – a Pathological Mystery

Indian Journal of Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery (2023)

-

Sclerosing Polycystic Adenosis Arising in the Parotid Gland Without PI3K Pathway Mutations

Head and Neck Pathology (2022)

-

Cribriform adenocarcinoma of the tongue and minor salivary glands: a systematic review of an uncommon clinicopathological entity

European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology (2022)