Abstract

A predominantly diffuse growth pattern and CD23 co-expression are uncommon findings in nodal follicular lymphoma and can create diagnostic challenges. A single case series in 2009 (Katzenberger et al) proposed a unique morphologic variant of nodal follicular lymphoma, characterized by a predominantly diffuse architecture, lack of the t(14;18) IGH/BCL2 translocation, presence of 1p36 deletion, frequent inguinal lymph node involvement, CD23 co-expression, and low clinical stage. Other studies on CD23+ follicular lymphoma, while associating inguinal location, have not specifically described this architecture. In addition, no follow-up studies have correlated the histopathologic and cytogenetic/molecular features of these cases, and they remain a diagnostic problem. We identified 11 cases of diffuse, CD23+ follicular lymphoma with histopathologic features similar to those described by Katzenberger et al. Along with pertinent clinical information, we detail their histopathology, IGH/BCL2 translocation status, lymphoma-associated chromosomal gains/losses, and assessment of mutations in 220 lymphoma-associated genes by massively parallel sequencing. All cases showed a diffuse growth pattern around well- to ill-defined residual germinal centers, uniform CD23 expression, mixed centrocytic/centroblastic cytology, and expression of at least one germinal center marker. Ten of 11 involved inguinal lymph nodes, 5 solely. By fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis, the vast majority lacked IGH/BCL2 translocation (9/11). Deletion of 1p36 was observed in five cases and included TNFRSF14. Of the six cases lacking 1p36 deletion, TNFRSF14 mutations were identified in three, highlighting the strong association of 1p36/TNFRSF14 abnormalities with this follicular lymphoma variant. In addition, 9 of the 11 cases tested (82%) had STAT6 mutations and nuclear P-STAT6 expression was detectable in the mutated cases by immunohistochemistry. The proportion of STAT6 mutations is higher than recently reported in conventional follicular lymphoma (11%). These findings lend support for a clinicopathologic variant of t(14;18) negative nodal follicular lymphoma and suggests importance of the interleukin (IL)-4/JAK/STAT6 pathway in this variant.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Follicular lymphoma is a common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, particularly in the United States and Western Europe, accounting for about 20% of all lymphomas.1 Most patients present with generalized lymphadenopathy and a prolonged clinical course. The prototypic histopathology is a proliferation of back-to-back lymphoid follicles, comprised of varying proportions of neoplastic centrocytes and centroblasts, and displaying an abnormal germinal center immunophenotype (CD10+, BCL6+, BCL2+). Most cases demonstrate cytogenetic evidence of the t(14;18)(q32;q21); BCL2/IGH translocation. Still, many variants of follicular lymphoma have been described that deviate from this prototype. These have been differentiated by anatomic location (eg, nodal, primary cutaneous, primary intestinal, or other extranodal), by patient age (eg, pediatric variant of follicular lymphoma) and/or by the presence or absence of the classic t(14;18) BCL2/IGH translocation.2 Even among nodal follicular lymphoma, several uncommon histologic variants can be seen, including floral variant, follicular lymphoma with marginal zone differentiation, pediatric variant, and diffuse follicular lymphoma.2 These subtypes are important to recognize because of their diagnostic and prognostic implications.

A unique morphologic variant of nodal follicular lymphoma was described in 2009 by Katzenberger and colleagues.3 Distinguishing features of this variant included a mostly diffuse pattern of growth, frequent inguinal involvement, and CD23 co-expression. Importantly, 28 of 29 cases in the series lacked t(14;18), while 27 of 29 revealed a deletion in the terminal portion of the short arm of chromosome 1 [del(1p36)]. Although the diffuse growth pattern and lack of t(14;18) were unusual for follicular lymphoma, the presence of at least focal atypical follicles and an unequivocal germinal center phenotype (both CD10+ and BCL6+) were helpful features for classification as follicular lymphoma. In addition, gene expression analysis performed on a small subset of the cases showed a profile within the spectrum of typical follicular lymphoma, albeit clustering as a distinct group, further suggesting that these represent a variant of follicular lymphoma. Although 1p36 aberrations also occur in conventional follicular lymphoma, the authors concluded that 1p36 deletion in the context of absent t(14;18) may represent a unifying chromosomal aberration for this distinctive variant. The high proportion of cases with CD23 expression was also unusual for follicular lymphoma, although CD23 expression occasionally is observed in conventional follicular lymphoma and has previously been associated with inguinal involvement.4, 5

Besides t(14;18) IGH/BCL2 rearrangement, other genomic abnormalities in conventional follicular lymphoma have become better elucidated in recent years by a variety of technologies. Follicular lymphoma is generally characterized by genomic gains of chromosomes 2 (and focally of 2p16-p15), 5, 7, 6p, 8 (8q24), 12 (12q12-q13), 17q, 18, 21, and X and losses on 6q (6q23-q24) and 17p.6 Smaller regional losses are also frequently detected at 1p36 and 10q23-q25.6 Several massively parallel sequencing studies have as well identified recurrent somatic mutations in follicular lymphoma, including KMT2D (MLL2), BCL2, CREBBP, EZH2, TNFRSF14, TP53, STAT6, EP300, PIM1, and CARD11.7, 8, 9, 10, 11 As genetic/molecular abnormalities become better defined, it is of biological and clinical interest to determine whether particular patterns of abnormalities are associated with specific histopathologic variants of follicular lymphoma and could potentially be incorporated in a clinical setting to assist in differential diagnosis.

Since the description by Katzenberger et al, no subsequent studies have confirmed the association of del(1p36) or detailed the histopathologic features, immunophenotypic patterns, or recurrent genetic/molecular abnormalities of the diffuse inguinal follicular lymphoma variant. Such cases remain a diagnostic problem, with features overlapping marginal zone lymphoma, small lymphocytic lymphoma, large B-cell lymphomas, or rarely even reactive hyperplasias. Accordingly, in this study, we describe a series of unusual CD23+ diffuse nodal B-cell lymphomas with histologic features partially overlapping those described in the entity proposed by Katzenberger et al. Our aim was to further define the clinical, histopathologic, immunophenotypic, and genetic characteristics of this diffuse nodal follicular lymphoma variant, with a comprehensive assessment of associated chromosomal aberrations and molecular abnormalities.

Materials and methods

Case Selection and Clinical Features

We identified 11 cases (over a 5-year period) of diffuse CD23+ follicular lymphoma with unifying histologic features, morphologically overlapping with the diffuse follicular lymphoma variant proposed by Katzenberger et al. These were obtained from the pathology archives of Los Angeles County/University of Southern California Medical Center and Keck Medical Center of USC. Cases that were CD10-negative were also included if all other features were compatible. Archived formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue was available for all cases. Clinical information was obtained from patient chart review. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Southern California (HS10-260).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining was performed on 4-μm tissue sections using the following antibodies: CD5 (clone 4C7), CD10 (clone 56C6), CD21 (clone 2G9), CD23 (clone 1B12), CD43 (clone MT1), BCL2 (clone bcl-2/100/D5), and BCL6 (clone LN22) from Leica Biosystems, Newcastle, UK; CD20 (clone L26) and Ki67 (clone MIB1) from Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA; Cyclin D1 (clone SP4) and LMO2 (clone SP51) from Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA, USA; LEF1 (clone EPR2029Y), STAT6 (clone YE361), and phospho-STAT6 (clone phospho Y641) from Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA. Immunostaining was performed on an automated Leica BOND III immunostainer (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA).

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization and Array Comparative Genomic Hybridization

Results of fluorescence in situ hybridization for t(14;18) IGH/BCL2 translocation were available for all 11 cases, either from review of the original pathology reports or, when not initially performed, fluorescence in situ hybridization was performed on 4-μm formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections using Vysis LSI IGH/BCL2 dual color, dual fusion translocation probes (Abbott Molecular, Des Plaines, IL, USA).

Genomic DNA was extracted from five 10-micron formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections, following confirmation of greater than 70% tumor burden, and targeted array comparative genomic hybridization was performed essentially as previously described.12 Briefly, if the bulk of the DNA was greater than 800 bp in size, heat fragmentation was performed until the bulk DNA was 400–800 bp. Similarly treated reference DNA (normal male:female genomic DNA, Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and the tumor DNA were differentially labeled and hybridized to a targeted oligonucleotide array representing genomic regions commonly altered in mature B-cell neoplasms (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) as previously described.12, 13 Data were extracted using Feature Extraction Version 10.7.3.1 (Agilent) and sites of gain/loss identified using the Rank segmentation algorithm within the Nexus Copy Number Analysis Software (Version 6.1, Biodiscovery Inc., Hawthorne, CA, USA) where an average log2 ratio change of ±0.3 was considered acceptable for a minimum of eight consecutive probes. All gains/loss were visually confirmed by examining log ratio profiles and all genomic coordinates are given according to the NCBIbuild37/hg19 assembly.

Targeted Massively Parallel Sequencing and Analyses

The same genomic DNA (with the exception of FL4 and FL6 where DNA was from sections adjacent to those used for array comparative genomic hybridization) was subjected to massively parallel sequencing of the exons of 220 genes reported to be frequently mutated in mature B-cell neoplasms (Supplementary Methods). Briefly, 250 ng of genomic DNA was sheared to an average size of 180 bp and libraries were prepared using the Kapa Hyper Prep kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Kapa Biosystems, Wilmington, MA, USA). Individual libraries were multiplexed and pooled to hybridize for 72 h with the targeted capture probes and, after washing and purification, were analyzed for size and quantity on a Bioanalyzer using the DNA1000 kit (Agilent Technologies). Pooled multiplexed libraries were sequenced on the Miseq Benchtop Sequencer (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Somatic single nucleotide variant identification

De-multiplexed paired sequencing reads were aligned using CLC Genomics Workbench version 2.1 (CLC bio, Waltham MA, USA). Across samples, the average read depth was 435 × (range 268 × –704 ×), where on average 96% of targets (range 90–98.9%) per sample had ≥95% of the target region with read depth of ≥100 ×. Variant calling and annotation was performed using the same software (Supplementary Methods). Variant filtering was performed to remove common single nucleotide polymorphism variants (according to Non-flagged dbSNP, 1000 Genomes Project, and HapMap databases). Following further annotation using the Wannovar tool (http://wannovar.usc.edu), additional variants were filtered: common single nucleotide polymorphism variants in ExAC non-coding and synonymous variants, those occurring in homopolymer regions, those predicted by SIFT and PolyPhen2 to be benign and tolerated, respectively, or with a variant allele frequency of <10%. Variants that passed these filter steps were considered potential somatic and functional variants and used for further downstream analyses.

Copy number variation identification

Genomic gain/loss information from sequencing data was estimated using the CNVkit software package (http://github.com/etal/cnvkit). Read alignment for each sample was used to infer coverage across pre-computed genome bins utilizing both targeted reads and nonspecifically captured off-target reads. Sequencing data derived for the same capture panel from eight Hapmap DNAs (NA21732, NA20845, NA20502, NA19672, NA18939, NA18524, NA18484, and HG03646) served as a pooled reference for normalization of read counts for each sample and correct for systemic biases (for example, the variance among binned read counts caused by such features as GC content, target density, and repetitive sequences). Segmentation of binned and normalized coverage values was achieved using circular binary segmentation within CNVkit. A log2 ratio of ±0.2 was considered acceptable for scoring gains/losses.

Results

Clinical, Morphologic, and Immunohistochemical Features

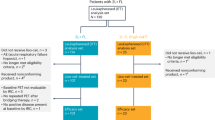

The clinical features of the patients with diffuse follicular lymphoma are given in Table 1, where the age at diagnosis ranged from 35 to 89 (mean 56.7 years), without gender predilection. Ten of 11 patients showed inguinal lymph node involvement, either alone (5 cases) or in the presence of other adenopathy (5 cases). The initial diagnostic biopsies were available for review in 10 of the 11 patients (an initial inguinal lymphoma diagnosed 2 years earlier was not available for FL11). Six patients were low stage (I–II) at presentation, while 4 had high stage disease (III–IV), of the 10 with available clinical information. Bone marrow involvement included diffuse (case FL1), diffuse and paratrabecular (case FL4; notably a CD10- case with partial paratrabecular pattern), and a very rare paratrabecular focal lymphoid aggregate (<5% cells), which was considered negative for clinical staging purposes (case FL9). Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index14 was high in three cases, intermediate in one, and low in six. Treatment ranged from RCHOP (rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) or similar chemoimmunotherapy (with or without maintenance rituximab) in five cases, excision alone in three cases, and radiation alone in two cases. Recurrence occurred in five cases at which time treatment was invariably rituximab-based chemotherapy (patient FL2 went on to receive autotransplantation). Time to progression (time from diagnosis to recurrence) ranged from 26 to 70 months (median 43). There was one death out of this cohort, a case characterized by advanced stage IV disease and recurrence after initial chemotherapy, but the median follow-up of survivors was 37 months. All patients achieved complete response after initial therapy.

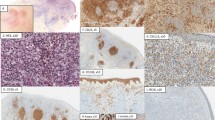

Histologically, all 11 cases in the study displayed a predominantly diffuse proliferation of pleomorphic lymphocytes (diffuse areas confirmed as lacking CD21+ follicular dendritic cells). In spite of the diffuse growth pattern, residual lymphoid follicles with reactive-appearing germinal centers were also present in all cases; in some cases, they were histologically intact with preserved mantle zones (Figure 1a), but in most patients, they were few, extremely ill-defined, partially colonized (Figure 1b), and only recognized by immunohistochemistry (CD10+, BCL6+, BCL2-, CD21+, high Ki67; Figure 1c and d,Table 2). Neoplastic B cells diffusely surrounded the residual follicles and consisted of a mixed population of centrocytes and centroblasts in varying proportions (Figure 2a); no significant plasmacytic or monocytoid differentiation was appreciable. The neoplastic B cells were uniformly CD20-positive (Figure 2b) and negative for CD5, CD43, Cyclin D1, and LEF1. Abundant small reactive T cells were admixed with neoplastic B cells (Figure 2c). CD21 staining of follicular dendritic cell networks was limited to a few residual follicles, while the lymphoma was devoid of staining (Figure 2d). In contrast, CD23 co-expression by the lymphoma cells was strong and uniform in all cases (Figure 2e). In 7/11 cases, the diffusely distributed lymphoma cells expressed both CD10 and BCL6 (Figure 2f and g), consistent with follicle center phenotype. The few residual follicles were BCL2-negative and demonstrated a higher Ki67 proliferation index, whereas the diffuse lymphoma showed variable expression of BCL2 and a lower proliferation index (Figure 2h and i). Whereas well-defined, residual follicles had sharply demarcated BCL2-negative germinal centers, ill-defined and partially colonized residual follicles displayed more variable, but mostly negative, BCL2 staining. In the four CD10− cases, distinction from marginal zone lymphoma was particularly difficult, but the cytological features and BCL6 and/or LMO2 expression were helpful for classification as follicular lymphoma, and the remaining hisopathologic features were quite similar to the CD10+ cases (Figures 3a–f). Relative proportions of centrocytes/centroblasts (cytologic grade) did not correlate with immunophenotype, clinical stage, or rates of recurrence.

Pathologic features of diffuse follicular lymphoma variant. The lymphoma shows a predominantly diffuse growth pattern. In all cases, at least focally, benign residual lymphoid follicles are present. In some areas, the residual follicles are well-defined, with polarized germinal centers and intact mantle zones (a, case FL2, H&E × 40). In other cases, the follicles are extremely ill-defined or not recognizable on H&E stain (b, case FL3, H&E × 40). However, even in the latter cases, immunohistochemical stains highlight the ill-defined residual follicles with CD21+ follicular dendritic cell networks (c, case FL3, × 40) and hot spots of increased proliferation on Ki67 stain (d, case FL3, × 40, similar area as shown in b).

Pathologic features of diffuse follicular lymphoma variant. Case FL10 (CD10-positive). (a) H&E × 40. (b) CD20 × 40. (c) CD3 × 40. (d) CD21 × 40; inset showing residual germinal center with partial CD21+ follicular dendritic cell networks (× 400). (e) CD23 × 40. (f) CD10 × 40. (g) BCL6 × 40. (h) BCL2 × 40. (i) Ki67 × 40.

(a–f): Pathologic features of diffuse follicular lymphoma variant, Case FL8 (CD10 negative). H&E stain (a) shows well-defined residual lymphoid follicles and a predominantly diffuse pattern of lymphoma (× 40), similar to that seen in other cases. High power shows a mixture of centrocytes and centroblasts (a, inset, × 400). CD20 (b) shows uniform staining of the diffuse lymphoma as well as residual follicles (× 40); CD23 (c) stains the diffuse lymphoma as well as follicular dendritic cell networks and mantle zones of residual follicles (× 40). In contrast to the case shown in Figure 2, CD10 (d) is negative in the lymphoma and only highlights residual germinal centers (× 100). However, BCL6 (e, × 100 and inset × 400) and LMO2 stains (f, × 100 and inset × 400) show staining in the diffuse lymphoma, consistent with germinal center phenotype. (g–i) Phospho-STAT6 immunohistochemistry. Reactive lymph node shows very rare to mostly absent staining for P-STAT6 (g, × 400). Case FL2, negative for STAT6 mutation, shows less than 1% nuclear staining for P-STAT6 (h, × 400). In contrast, case FL7, positive for STAT6 mutation, shows about 20% nuclear staining for P-STAT6 (i, × 400).

Structural Genomic Alterations

Consistent with the findings of Katzenberger et al, most cases of this diffuse follicular lymphoma variant lacked t(14;18) IGH/BCL2 translocation as assessed by fluorescence in situ hybridization (9 of 11 cases, Table 2). To examine genomic gain and loss, array comparative genomic hybridization was performed for all cases using a custom array designed to detect imbalance at chromosomal sites commonly altered in mature B-cell neoplasms. Nine of 11 cases exhibited whole or partial chromosome gains/losses (Table 2). Genomic imbalance information was also inferred from the sequencing panel (using both on- and off-target reads). Gain/loss of the sex chromosomes was not assessed by either platform. Of the 34 total gains/losses detected across the specimens by array comparative genomic hybridization, 29 were also detected through sequencing, confirming the latter approach. In one case (FL7), genomic gain/loss was only detected by sequencing and not array comparative genomic hybridization. Variability between genomic imbalance detected by array comparative genomic hybridization and sequencing could potentially be accounted for by the differing sensitivity and regions represented between the two platforms. In all, 10 of 11 cases showed at least one chromosomal gain/loss.

The studies of Katzenberger et al3 indicated that their diffuse follicular lymphoma variant is frequently characterized by deletion of 1p36. In the current study, five cases showed 1p36 loss and another case a partial loss, but all included TNFRSF14, the suggested candidate gene for this deletion in follicular lymphoma. Two of these cases also had concurrent IGH/BCL2 translocation. Other recurrent alterations included gains of 2p in four cases (focal, including REL and BCL11A), 3q and 12q in three cases, and 1q, 6p, and 9q in two cases each, with losses of 4q detected in three cases, and of 11q, 16p, and 16q in two cases each. However, no cases exhibited gain of chromosome 18 (typically observed in about 30% of follicular lymphoma) and only one case had 6q loss (seen in 25% of follicular lymphoma).6

Targeted Mutation Profile of the Follicular Lymphoma Variant

Mutations (single nucleotide variants and small insertions/deletions) were detected in all specimens across 51 out of 220 genes sequenced as part of a panel specifically designed to assess mutations in genes with relevance in follicular lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (Figure 4). Candidate mutations were considered only at frequencies of 10% and higher, and only those occurring in exons were considered. Of the 51 genes, only 8 exhibited recurrent mutations across the 11 cases. Multiple mutations were detected in BCL2 in cases FL2 and FL3 only, also the only two cases positive for t(14;18), consistent with BCL2 hypermutation reported in t(14;18)+ follicular lymphoma cases.10 MEF2B and ETS1 mutations were detected in three and two cases each, where the former has been reported in follicular lymphoma but with low frequency.7 Four cases had mutations in EZH2, at a roughly comparable frequency with that found for follicular lymphoma, but mutations in KMT2D (six cases) were relatively underrepresented.8, 15 Mutations were not detected in TP53, which is generally detected in about 15–25% of follicular lymphoma.10 On the other hand, mutations in TNFRSF14 (five cases), CREBBP (seven cases), and STAT6 (nine cases) were enriched in this follicular lymphoma variant compared with that reported for conventional follicular lymphoma.7, 10 For TNFRSF14, only two of the cases with 1p36 deletion also harbored mutation, one each of a frameshift deletion and nonsynonymous mutation. Two other cases with mutations were stopgain single nucleotide variants and the last was a nonsynonymous mutation reported in COSMIC. Overall then, nine cases of the follicular lymphoma variant had deletion and/or mutation of TNFRSF14. In conventional follicular lymphoma, STAT6 mutations have been reported in about 11% of cases,16 but in this variant, 9 of 11 cases (>80%) bore mutations. Across the nine cases, seven different single nucleotide variants were detected including two in each of two cases. Five cases of the nine exhibited mutations within codon 419 (Asp), a reported hot spot for mutation in follicular lymphoma.16 Of the remaining four cases, three had variants previously observed in lymphoid neoplasms according to COSMIC (http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic).

STAT6 and Phospho-STAT6 Immunohistochemistry

Given the high prevalence of STAT6 mutations detected in these cases, we tested whether nuclear STAT6 or phosphorylated STAT6 could be detected by immunohistochemistry, perhaps reflecting functional activation. STAT6 staining showed considerable cytoplasmic immunoreactivity, mostly obscuring any potential nuclear signal in reactive lymphoid tissue or lymphoma cases. Phospho-STAT6 immunohistochemistry was significantly easier to interpret, because P-STAT6 showed no cytoplasmic background staining. No significant phospho-STAT6 expression was detectable in reactive lymph node (Figure 3g) or in case FL2 (negative for STAT6 mutation, less than 1% staining). In contrast, all eight cases with STAT6 mutation available for staining showed scattered nuclear positivity for phospho-STAT6 (10–20%, Figure 3i).

Discussion

The distinctive clinical, morphologic, immunohistochemical, and genetic findings described in this study lend support for a variant of t(14;18) negative nodal follicular lymphoma and suggests the importance of the IL-4/JAK/STAT6 pathway in this variant. The two main unifying histopathologic features of this variant were: (i) a predominantly diffuse growth pattern of mixed centrocytic/centroblastic cells expressing CD20 and CD23 with co-expression of at least one germinal center marker (CD10, BCL6, and/or LMO2); and (ii) variably present residual, benign lymphoid follicles surrounded by the lymphoma which were usually ill-defined and only recognizable by immunohistochemistry (CD10+, BCL6+, BCL2−, high Ki67) but occasionally well-defined with circumscribed germinal centers and intact mantle zones. Ancillary genetic analyses of these cases both for genomic structural variants and mutations revealed several defining genetic features compared with conventional follicular lymphoma. This follicular lymphoma variant was genetically characterized by a high incidence of mutation in STAT6 and CREBBP, and loss or mutation of TNFRSF14, and comparatively reduced frequency of KMT2D, BCL2 mutations, and t(14;18) IGH/BCL2 rearrangement, and lack of gain of 18q and mutation of TP53.

The histopathologic features of this follicular lymphoma variant deviated quite significantly from conventional follicular lymphoma. Indeed, several cases in this study were initially classified as nodal marginal zone lymphoma, low grade B-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified, or even diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. In particular, CD10-negative diffuse follicular lymphoma is difficult to separate from marginal zone lymphoma. In a brief reference to diffuse follicular lymphoma in the 2008 WHO classification, centrocytic/centroblastic morphology, with germinal center immunophenotype or presence of classical t(14;18) translocation, are required for diagnosis.1 Even in the study by Katzenberger et al3 on diffuse nodal follicular lymphoma, CD10 was reported as positive in all cases, at least in the follicular component of the tumors, and positive in 30/35 cases in the diffuse areas. It could be argued that a t(14;18)-negative B-cell lymphoma with diffuse growth pattern, surrounding benign residual follicles, and lacking CD10 expression should not truly be considered a follicular lymphoma variant but could instead represent marginal zone lymphoma with partial follicular colonization or partial involvement by conventional follicular lymphoma. However, the CD10-negative and CD10-positive cases appear otherwise indistinguishable with very similar patterns (frequent involvement of inguinal sites, diffuse growth of centrocytes/centroblasts around residual well-defined or ill-defined/partially colonized follicles, CD23 expression, expression of at least one germinal center marker, and patterns of cytogenetic and molecular abnormalities). The paratrabecular involvement of bone marrow seen in two cases (one CD10+ and one CD10−) also supports follicular lymphoma. Finally, in one of our cases (case FL2), CD10 was negative in the diffuse inguinal lymphoma at diagnosis. Three years later at recurrence (same inguinal site), a concurrently biopsied intraparotid lymph node showed a CD10+ lymphoma. All three biopsies were diffusely CD23+ and this was a rare t(14;18) positive case.

Unlike chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, where CD23 expression is a defining feature, CD23 expression in follicular lymphoma occurs, but is uncommon. In addition to the work of Katzenberger et al and our study, at least two other groups have reported that CD23 expression is more common in inguinal follicular lymphoma.4, 5 These had histologic features similar to conventional follicular lymphoma, including follicular growth pattern, CD10 expression, and the presence of t(14;18). Thorns et al4 reported a diffuse growth pattern in 22% of inguinal follicular lymphoma, but these were not increased relative to follicular lymphoma at other sites (27%) and there was no specific mention of CD23 in the diffuse cases. Notably, neither of these studies highlighted histologic variants similar to those reported by Katzenberger et al or in the current series. This may be due to the relative rarity of this subtype, even among CD23+ inguinal follicular lymphoma. It is also possible that the unusual pattern may have been interpreted as evidence of nodal marginal zone lymphoma in some of the cases. Interestingly, CD10+ marginal zone lymphoma has been described, curiously also involving inguinal nodes.17 Whether this represents a clinicopathologic gray zone between diffuse follicular lymphoma as described here and marginal zone lymphoma remains to be determined. Re-evaluation of previous studies of CD23+ follicular lymphoma and nodal marginal zone lymphoma to determine whether cases compatible with this variant can be identified is warranted, and also to measure their relative proportions among non-Hodgkin lymphomas.

Between the series of defining cases presented by Katzenberger et al and those currently described, most features were comparable, but some differences were noted. Some of the differences may be attributable to slightly different inclusion criteria: we selected cases with diffuse growth pattern and CD23 expression, whereas the prior series selected only diffuse follicular lymphoma (defined as <25% follicularity). Still, CD23 was positive in 77% of their cases (vs 100% in ours). The histologic patterns, as detailed above, were quite similar with predominantly diffuse growth and occasionally intermingled follicles. Whereas we emphasize the presence of benign follicles seen in all of our cases (ill-defined, occasionally well-defined), the nature of these follicles was not detailed in the prior study. Instead, ‘atypical follicles’ with increased CD10 and BCL6 and increased Ki67 were described for all cases. BCL2 expression in these follicles was reported as variable, ranging from entirely negative to moderately strong in most of the germinal center cells, although the frequency of strong BCL2 expression in the follicles was not reported. We suspect that the follicles with ‘moderately strong BCL2 staining in most of the germinal center cells’ may have represented ill-defined/colonized follicles, as seen in some of our cases. Accordingly, we favor at least the majority of the follicular structures in this variant to represent residual benign germinal centers. Additional similarities between the Katzenberger et al series and ours include involvement of the inguinal region (85% in Katzenberger et al vs 82% in the current study) and absence of t(14;18) translocation (97% vs 82%, respectively).

Although there is considerable overlap between the follicular lymphoma variant described by Katzenberger et al and this series, significant differences were also seen. We suggest that this variant can be broadened to include CD10-negative cases if other characteristics are present. Stage of disease in our series was also more heterogeneous, with 4/11 patients showing high stage. The response to treatment in this cohort was similar to what is reported for conventional follicular lymphoma with patients typically responding to initial chemotherapy but relapsing after 3 to 5 years.18 Of note, 1p36 deletion (found in 93% of cases presented by Katzenberger et al and considered characteristic) was observed in five (45%) of our cases, at a similar frequency of occurrence seen in conventional follicular lymphoma.19 This reduced incidence may challenge the notion that the previous and current series represent the same follicular lymphoma variant, although the possibility that it may be attributable to differences in analytical sensitivity of array comparative genomic hybridization and massively parallel sequencing for evaluation of genomic gain/loss compared with fluorescence in situ hybridization was considered. Importantly, we show that the 1p36 deletion in these cases included TNFRSF14, a recurrently involved region in conventional follicular lymphoma.20, 21, 22 Moreover, in the six cases lacking detectable 1p36 deletion in our series, another three demonstrated mutations in TNFRSF14, confirming that 1p36/TNFRSF14 abnormalities, whether by deletion or mutation, are strongly correlated with this variant. These data suggest that a combined approach assessing for chromosomal loss at 1p36 and TNFRSF14 mutation analysis may be necessary to identify these cases.

In the current study, further molecular characterization of this follicular lymphoma variant was performed. This comprised the detection of other recurrent genomic structural aberrations including the loss of 4q34-q35, gain of 3p, 3q, and 12q, all of which can be seen in conventional follicular lymphoma,23, 24, 25, 26 but are detected at higher frequencies in nodal marginal zone lymphomas.27, 28 Gains of 2p (four cases with three as focal gains of REL, at higher frequency than observed in follicular lymphoma), 9q, and 11p were also recurrently observed. When examining the mutational profile of this CD23+ follicular lymphoma variant for genes frequently involved in mature B-cell neoplasms, it was evident that for most genes, mutation frequencies were comparable with those observed in conventional follicular lymphoma, but others were relatively underrepresented (KMT2D, TP53) or enriched (TNFRSF14, CREBBP, and STAT6).7, 8, 10, 15, 16 Such a mutational profile could be useful in distinguishing such cases in a diagnostic setting. For instance, at least two of the three CD10− cases, particularly difficult to separate from nodal marginal zone lymphoma, carried STAT6 mutations. According to COSMIC, the overall mutational profile of marginal zone lymphoma is quite distinct from follicular lymphoma where the former is enriched for mutations in NOTCH2, TNFAIP3, MYD88, TP53, and NOTCH1, with no reported STAT6 mutations. Of these five genes, only one case each showed a mutation in NOTCH2 or NOTCH1 (FL3 and 1, respectively), of which the former was CD10+ and the latter CD10− but bore a STAT6 mutation. Presence of diffuse, uniform CD23 expression, in the context of bulky inguinal disease, centrocytic/centroblastic morphology, and expression of at least one germinal center marker, may also assist in making this diagnosis. Recently, STAT6 mutations have been demonstrated in a minority of follicular lymphoma cases, 11–12% in follicular lymphoma and 23% in transformed follicular lymphoma, where it was unclear whether STAT6 mutation was associated with differing histologies or t(14;18) status.10, 15, 16 Perhaps P-STAT6 immunohistochemistry could serve as surrogate for STAT6 mutation in this follicular lymphoma variant, although the specificity of this assertion requires a more comprehensive study. Of note, we stained 33 cases of conventional follicular lymphoma for P-STAT6 and CD23 and did not see an association between CD23 expression and nuclear P-STAT6 immunoreactivity, at least for conventional follicular lymphoma (unpublished data).

The high incidence of STAT6 mutations in this variant is striking. It has been proposed that IL-4 produced by follicular helper T cells in the tumor microenvironment binds to IL-4 receptors on lymphoma cells. IL-4 thereby activates Jak1 and Jak3 which leads to phosphorylation, dimerization, and translocation of STAT6 to the nucleus.29, 30 STAT6 mutations in follicular lymphoma were reported to be mostly activating, with a hot spot at amino acid 419.16 Herein, we demonstrate STAT6 mutations in the majority of the cases of this diffuse variant of nodal follicular lymphoma (80%), where five cases bore the aa419 hot spot mutation. This finding suggests a potential importance of the IL-4/JAK/STAT6 pathway in this variant. Further studies are required to better understand the relevant targets of STAT6, which interestingly include CD23,31 and the potential role of this pathway in the etiology of this variant. The broader role the microenvironment may have in these cases, given their unique architecture, should also be further evaluated. STAT6 abnormalities in this lymphoma variant may be of therapeutic relevance. STAT6 has been targeted in the setting of Hodgkin lymphoma via the histone deacetylase inhibitor, vorinostat.32 This has been shown to inhibit STAT6 phosphorylation and was associated with a decrease in expression of chemokine Thymus and Activation-Regulated Chemokine and cytokine IL-5. Histone deacetylase inhibition is thought to exert antitumor effect via this immune regulation. Development of this therapeutic strategy is of particular value as it might provide a synergistic effect with conventional chemotherapy.

In summary, we characterize a series of diffuse nodal follicular lymphomas with distinctive histopathology and immunophenotype, frequently lacking IGH/BCL2 translocation and often involving the inguinal region. This variant demonstrates distinct patterns of genomic gain and loss and higher frequencies of TNFRSF14, CREBBP, and STAT6 mutations compared with conventional follicular lymphoma. Patients may present with low or high stage disease. These findings lend support for a clinicopathologic subtype of follicular lymphoma.

References

Harris NL, Nathwani BN, Swerdlow SH et al. Follicular lymphoma In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J, Vardiman JW (eds). WHO Classification of Tumors of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues 4th edn. IARC: Lyon, France, 2008, pp 220–226.

Jaffe ES . Follicular lymphomas: a tapestry of common and contrasting threads. Haematologica 2013;98:1163–1165.

Katzenberger T, Kalla J, Leich E et al. A distinctive subtype of t(14;18)-negative nodal follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma characterized by a predominantly diffuse growth pattern and deletions in the chromosomal region 1p36. Blood 2009;113:1053–1061.

Thorns C, Kalies K, Fischer U et al. Significant high expression of CD23 in follicular lymphoma of the inguinal region. Histopathology 2007;50:716–719.

Olteanu H, Fenske TS, Harrington AM et al. CD23 expression in follicular lymphoma: clinicopathologic correlations. Am J Clin Pathol 2011;135:46–53.

Bouska A, McKeithan TW, Deffenbacher KE et al. Genome-wide copy-number analyses reveal genomic abnormalities involved in transformation of follicular lymphoma. Blood 2014;123:1681–1690.

Morin RD, Mendez-Lago M, Mungall AJ et al. Frequent mutation of histone-modifying genes in non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Nature 2011;476:298–303.

Bödör C, Grossmann V, Popov N et al. EZH2 mutations are frequent and represent an early event in follicular lymphoma. Blood 2013;122:3165–3168.

Correia C, Schneider PA, Dai H et al. BCL2 mutations are associated with increased risk of transformation and shortened survival in follicular lymphoma. Blood 2015;125:658–667.

Pasqualucci L, Khiabanian H, Fangazio M et al. Genetics of follicular lymphoma transformation. Cell Rep 2014;6:130–140.

Li H, Kaminski MS, Li Y et al. Mutations in linker histone genes HIST1H1 B, C, D, and E; OCT2 (POU2F2); IRF8; and ARID1A underlying the pathogenesis of follicular lymphoma. Blood 2014;123:1487–1498.

Dias LM, Thodima V, Friedman J et al. Cross-platform assessment of genomic imbalance confirms the clinical relevance of genomic complexity and reveals loci with potential pathogenic roles in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 2015;21:1–27 ..

Houldsworth J, Guttapalli A, Thodima V et al. Genomic imbalance defines three prognostic groups for risk stratification of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma 2014;55:920–928.

Solal-Celigny P, Roy P, Colombat P et al. Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index. Blood 2004;104:1258–1265.

Okosun J, Bödör C, Wang J et al. Integrated genomic analysis identifies recurrent mutations and evolution patterns driving the initiation and progression of follicular lymphoma. Nat Genet 2014;46:176–181.

Yildiz M, Li H, Bernard D et al. Activating STAT6 mutations in follicular lymphoma. Blood 2015;125:668–679.

Wang E, West D, Kulbacki E . An unusual nodal marginal zone lymphoma with bright CD10 expression: a potential diagnostic pitfall. Am J Hematol 2010;85:546–548.

Johnson PW, Rohatiner AZ, Whelan JS et al. Patterns of survival in patients with recurrent follicular lymphoma: a 20-year study from a single center. J Clin Oncol 1995;13:140–147.

Dave BJ, Hess MM, Pickering DL et al. Rearrangements of chromosome band 1p36 in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res 1999;5:1401–1409.

Martin-Guerrero I, Salaverria I, Burkhardt B et al. Recurrent loss of heterozygosity in 1p36 associated with TNFRSF14 mutations in IRF4 translocation negative pediatric follicular lymphomas. Haematologica 2013;98:1237–1241.

Launay E, Pangault C, Bertrand P et al. High rate of TNFRSF14 gene alterations related to 1p36 region in de novo follicular lymphoma and impact on prognosis. Leukemia 2012;26:559–562.

Cheung KJ, Johnson NA, Affleck JG et al. Acquired TNFRSF14 mutations in follicular lymphoma are associated with worse prognosis. Cancer Res 2010;70:9166–9174.

Cheung KJ, Shah SP, Steidl C et al. Genome-wide profiling of follicular lymphoma by array comparative genomic hybridization reveals prognostically significant DNA copy number imbalances. Blood 2009;113:137–148.

Cheung KJ, Delaney A, Ben-Neriah S et al. High resolution analysis of follicular lymphoma genomes reveals somatic recurrent sites of copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity and copy number alterations that target single genes. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2010;49:669–681.

Viardot A, Möller P, Högel J et al. Clinicopathologic correlations of genomic gains and losses in follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:4523–4530.

Schwaenen C, Viardot A, Berger H et al. Molecular Mechanisms in Malignant Lymphomas Network Project of the Deutsche Krebshilfe. Microarray-based genomic profiling reveals novel genomic aberrations in follicular lymphoma which associate with patient survival and gene expression status. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2009;48:39–54.

Braggio E, Dogan A, Keats JJ et al. Genomic analysis of marginal zone and lymphoplasmacytic lymphomas identified common and disease-specific abnormalities. Mod Pathol 2012;25:651–660.

Krijgsman O, Gonzalez P, Ponz OB et al. Dissecting the gray zone between follicular lymphoma and marginal zone lymphoma using morphological and genetic features. Haematologica 2013;98:1921–1929.

Neelapu SS . Mutations and microenvironment collude in FL. Blood 2015;125:587–589.

Pangault C, Amé-Thomas P, Ruminy P et al. Follicular lymphoma cell niche: identification of a preeminent IL-4-dependent T(FH)-B cell axis. Leukemia 2010;24:2080–2089.

Kneitz C, Goller M, Seggewiss R et al. STAT6 and the regulation of CD23 expression in B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Res 2000;24:331–337.

Buglio D, Georgakis GV, Hanabuchi S et al. Vorinostat inhibits STAT6-mediated TH2 cytokine and TARC production and induces cell death in Hodgkin lymphoma cell lines. Blood 2008;112:1424–1433.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

JF, CM, VT, LD, SK, and JH are employees and stock option holders of Cancer Genetics, Inc. JH is also a stock holder of Cancer Genetics, Inc.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Siddiqi, I., Friedman, J., Barry-Holson, K. et al. Characterization of a variant of t(14;18) negative nodal diffuse follicular lymphoma with CD23 expression, 1p36/TNFRSF14 abnormalities, and STAT6 mutations. Mod Pathol 29, 570–581 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.51

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.51

This article is cited by

-

Klassifikation indolenter B-Zell-Lymphome

Die Pathologie (2023)

-

Follicular lymphoma and marginal zone lymphoma: how many diseases?

Virchows Archiv (2023)

-

Oral follicular lymphoma: a clinicopathologic and molecular study

Journal of Hematopathology (2023)

-

The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Lymphoid Neoplasms

Leukemia (2022)

-

CREBBP and STAT6 co-mutation and 16p13 and 1p36 loss define the t(14;18)-negative diffuse variant of follicular lymphoma

Blood Cancer Journal (2020)