Abstract

Deletion 7q is a common chromosomal abnormality in myeloid neoplasms. Detection of del(7q) in patients following cytotoxic therapies is highly suggestive of an emerging therapy-related myeloid neoplasm. In this study, we describe 39 patients who acquired del(7q) as a sole abnormality in their bone marrow following cytotoxic therapies for malignant neoplasms. The median interval from cytotoxic therapies to detection of del(7q) was 40 months (range, 4–190 months). Twenty-eight patients showed an interstitial and 11 showed a terminal 7q deletion. Fifteen patients (38%) had del(7q) as a large clone and 24 (62%) as a small clone. With a median follow-up of 21 months (range, 1–135 months), 18 (46%) patients developed therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, including all 15 patients with a large del(7q) clone and 3/24 (12.5%) with a small clone. Of the remaining 21 patients with a small del(7q) clone, 16 showed no evidence of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms and 5 had an inconclusive pathological diagnosis. We conclude that isolated del(7q) emerging in patients after cytotoxic therapy may not always be associated with therapy-related myeloid neoplasms in about half of patients. The clone size of del(7q) is critical; a large clone is almost always associated with therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, whereas a small clone can be a clinically indolent or transient finding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Abnormalities of chromosome 7, either monosomy (−7) or deletion of the long arm (del(7q)), are the most common cytogenetic abnormalities detected in acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes.1, 2, 3 Del(7q)/−7 occurs in ~8% of de novo acute myeloid leukemia and ~10% of de novo myelodysplastic syndromes.1, 4 Del(7q) has been classified as the intermediate-II risk group in de novo acute myeloid leukemia5 and the intermediate risk group in de novo myelodysplastic syndromes, respectively.6 Therapy-related myeloid neoplasm is a late complication of cytotoxic therapies for primary malignant and non-malignant diseases. Cytogenetic abnormalities can be detected in more than 90% of patients with therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, and more than half of these patients have a complex karyotype.7 Del(7q)/−7 presents in ~50% of patients with therapy-related myeloid neoplasms and are often associated with prior exposure to alkylating agents or ionizing radiation.1, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Any newly emerged cytogenetic abnormalities in patients with a prior history of cytotoxic therapies often raises the concern of development of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, especially when the abnormalities include del(7q)/−7.

In our practice, we have observed that some patients develop isolated del(7q) in their bone marrow following cytotoxic therapies, yet never develop therapy-related myeloid neoplasms with close follow-up. In order to better understand the frequency and clinical significance of this occurrence, we retrospectively searched our archives for patients who acquired isolated del(7q) following cytotoxic chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. We performed a detailed clinical, pathological and cytogenetic review in all patients, and performed fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in a subset of patients.

Materials and methods

Patients

We searched the clinical cytogenetics laboratory database at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center from January 2003 to December 2014 for del(7q) as a sole clonal abnormality. These patients were further screened for a history of cytotoxic therapies. A detailed chart review was conducted in all patients. The diagnoses of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, including therapy-related myelodysplastic syndromes, therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia and therapy-related chronic myelomonocytic leukemia were based on receiving prior cytotoxic chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy, plus clinical and morphologic criteria for acute myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes and/or chronic myelomonocytic leukemia as specified in the WHO classification.13 All samples were collected following institutional guidelines with informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Peripheral Blood and Bone Marrow Assessments

Peripheral blood smears, bone marrow aspirate smears and trephine biopsy specimens were evaluated for morphologic evidence of dysplasia, percentage of blasts and bone marrow cellularity. Dyserythropoiesis included cytoplasmic vacuolization, ring sideroblasts, nuclear budding and internuclear bridging; dysgranulopoiesis included bilobed nuclei or nuclear hypolobation in neutrophils (eg, pseudo-Pelger-Huet anomaly), cytoplasmic vacuoles and hypogranulation; dysmegakaryocytosis included micromegakaryocytes and nuclear hypolobation. The criteria for significant/marked dysplasia applied in the study were dysplasia presenting in ≥10% of cells in at least one lineage;1 dysplasia in 5–10% cells was considered mild dysplasia. Complete blood cell counts at the time of del(7q) detection and during follow-up were reviewed. Cytopenia was defined as hemoglobin <13 g/dl (male) or <12 g/dl (female), neutrophils <1.8 × 109/l or platelets <140 × 109/l. The involvement of bone marrow by the primary cancer was evaluated by morphological, immunohistochemical and/or flow cytometry immunophenotyping analysis.

Conventional Cytogenetics Analysis

Conventional chromosomal analysis was performed on G-banded metaphases prepared from unstimulated 24- and 48-h bone marrow aspirate cultures (for primary diagnosis of myeloid neoplasms or solid tumors) or unstimulated 24-h and mitogen-stimulated 72-h bone marrow aspirate cultures (for primary diagnosis of lymphoma or myeloma) using standard techniques. Mitogens included lipopolysaccharide, oligonucleotides and 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate. Twenty metaphases were analyzed and the results were reported using the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature (ISCN 2013).14 A large clone was designated as ≥40% of metaphases with del(7q), and a small clone as ≤35% of metaphases with del(7q).

FISH Analysis

FISH analysis was performed in a subset of patients with the dual color D7S522 (7q31, spectrum red)/CEP7 (spectrum green) probes (Abbott Molecular). Two hundred nuclei were counted and the percentage of cells with del(7q) was calculated. The positive cutoff value for del(7q) established in our laboratory is 3.6%. Combined morphologic-FISH analysis was performed as described previously.15

Results

Patients

A total of 110 patients with isolated del(7q) in the bone marrow were identified during the study interval; of those, 43 patients had been previously treated with cytotoxic therapies for prior malignancies. Four patients were further excluded due to an inconclusive diagnosis and a short follow-up period. The study included 39 patients, 20 men and 19 women, with a median age of 62 years (range: 35–81 years). Primary malignancies for which the patients had been treated included solid tumors (n=9), lymphoid neoplasms (n=29), acute myeloid leukemia (in remission, n=3), and three patients (cases 2, 9 and 12) had two malignancies (Table 1). Prior therapies included chemotherapy alone (n=25), radiotherapy alone (n=1) and chemotherapy plus radiotherapy (n=13). Ten patients also received stem cell transplantation following cytotoxic therapies (Table 1) (the detailed therapeutic information is listed in Supplementary Material).

Bone Marrow and Peripheral Blood Findings

At the time of detection of del(7q), the bone marrow was found to be involved by the primary malignancy in six patients; three patients (cases 12, 20 and 39) had substantial (40–90%) bone marrow involvement by chronic lymphocytic leukemia, plasma cell myeloma or T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia, respectively, and the other three patients (cases 2, 7 and 10) had minimal (5–10%) bone marrow involvement by low-grade B-cell lymphoma, thyroid cancer or follicular lymphoma, respectively (Table 1).

Morphological assessment was performed without knowledge of cytogenetic findings. Twelve patients (cases #1–12 in Table 1) showed increased bone marrow blasts and/or marked dyspoiesis, meeting the WHO criteria for therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, including therapy-related myelodysplastic syndromes (n=10, 4 with blasts 7–12%), therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia (n=1, case #9 blasts 30%) and therapy-related chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (n=1, case #5, blasts 10%). Of the remaining 27 patients, blasts were not increased and criteria for therapy-related myeloid neoplasms were not met in the diagnostic bone marrow sample at the time of del(7q) identification. This group included 10 patients (cases 13–15, 19–25) with mild dysplasia, 16 patients (cases 16–18, 26–38) who did not have dysplasia and 1 patient in whom morphological assessment was difficult due to significant involvement by lymphoma (case 39) (Figure 1).

At the time of del(7q) detection, all 12 patients with WHO-defined therapy-related myeloid neoplasms demonstrated abnormal complete blood cell counts consistent with t-MN diagnosis. Of the 10 patients with mild dyspoiesis, 7 (patients 15, 19–24) showed a variable degree of cytopenia and 3 (patients 13, 14, 25) had normal complete blood cell counts. Of the 16 patients who showed no evidence of dysplasia, 6 (cases 16–18, 26–28) demonstrated mild cytopenia and the other 10 patients (cases 29–38) had normal complete blood cell counts (Figure 1). Patient 39 showed marked leukocytosis in the setting of active T-PLL.

Conventional Cytogenetic and FISH Analysis

Baseline cytogenetic information before the initiation of cytotoxic therapy was available in 19 patients, 9 had a normal diploid karyotype and 10 had various chromosomal abnormalities associated with their respective primary disease, including inv(16)(p13.1;q22) (cases 23 and 28), t(9;22)(q34;q11.2) (case 34), t(1;19)(q23;p13.3) (case 31), t(11;14)(q13;q32) (case 11 and 24), +12 (case 17), t(14;18)(q32;q21.3) (case 22) and a complex karyotype in cases 18 and 32. None of the patients showed del(7q) prior to initiation of cytotoxic therapies. The median interval from the initiation of cytotoxic therapy to the detection of del(7q) was 48 months (range, 4–190 months) (Table 1).

The median percentage of metaphases with del(7q) was 20% (range, 10–100%). Del(7q) presented as a large clone (≥40% metaphases) in 15 patients and as a small clone (<40% metaphases) in 24 patients. All 15 patients (cases 1–14, 16) with a large clone were diagnosed with therapy-related myeloid neoplasms either at the time of del(7q) detection (n=12) or at follow-up bone marrow examination (n=3). Of the 24 patients with a small del(7q) clone identified, only 3 patients (cases 15, 17, 18) were ultimately diagnosed with therapy-related myeloid neoplasms during the follow-up period.

Deletions in 7q included terminal (n=11) and interstitial deletions (n=28). The breakpoints in patients with terminal deletions were at 7q22 (n=9), 7q11.2 (n=1) and 7q32 (n=1). For interstitial deletions, the common breakpoints were at 7q22 at the centromeric site or 7q32, 7q34 and 7q36 at the telomeric site. Of the three common deleted regions on 7q, common deleted region 1 (7q22), common deleted region 2 (7q34) and common deleted region 3 (7q35–36), 18 patients had all three common deleted regions deleted, 15 patients did not involve commonly deleted region 3, 5 patients (cases 13–15, 23, 27) did not involve common deleted regions 2 and 3; and 1 patient (case 39) did not involve common deleted region 1 (Table 1).

FISH analysis using D7S522/CEP7 probes was performed in 21 patients. One patient (case 15) showed a negative result (as the deletion did not involve the D7S522 locus) and 20 patients showed a D7S522 (7q31) deletion involving 5–97% of interphases (Table 1). Overall, the percentage of interphases showing D7S522 (7q31) deleted by interphase FISH was slightly lower but proportionally correlated with the percentage of metaphases with del(7q) detected by conventional karyotyping (r=0.946).

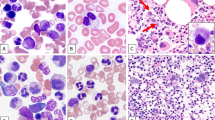

Combined morphologic-FISH analysis was performed in two cases. Case 9 (primary CLL/SLL and MCL, followed by therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia) showed del(7q) in myeloblasts, erythroblasts and maturing granulocytes, but not in lymphocytes (Figures 2a and b). Case 29 (negative bone marrow) showed del(7q) in 26% of hematopoietic cells (erythroblasts and maturing myeloid cells), but not in lymphocytes (Figures 2c and d).

Combined morphologic-FISH analysis. (a, c) Wright-Giemsa stain on bone marrow aspirate smear; (b, d) FISH analysis using dual color D7S522 (red)/CEP7 (green) probes. (a, b) Case 9 with therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia. Del(7q) was presented in blasts, erythrocytes and maturing granulocytes, not in lymphocyte (marked with arrow). (c, d) Case 29 with negative bone marrow. Del(7q) was presented in one granulocyte and one erythroblasts (marked with arrow head), not in lymphocyte (marked with arrow).

Follow-up and Outcomes

The median follow-up after detection of del(7q) was 21 months (range, 1–135 months). Twenty-seven patients had at least one follow-up karyotype (median 2, range 1–10) after the initial del(7q) identification. Del(7q) was persistently detected in 15 patients (including 13 patients who were ultimately diagnosed with therapy-related myeloid neoplasms), and became undetectable in 12 patients (11 who were not diagnosed with therapy-related myeloid neoplasms). Two patients (cases 15 and 17) showed clonal evolution with additional chromosomal abnormalities after 8 and 22 months respectively, and 2 patients (cases 18 and 36) had new unrelated clones that emerged after del(7q) disappeared, specifically case 18 showed 45,XY,der(6;7)(p10;q10)[4]/46,XY,add(11)(p15)[3]/46,XY[13], and case 36 showed 46,XY,del(11)(q22q23)[16]/46,XY[4].

Patient 19 experienced persistent anemia and worsening thrombocytopenia during follow-up, a diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndrome was highly suspicious though no follow-up bone marrow biopsy was performed, and he died at 4 months after the original detection of del(7q). Two patients (cases 20, 21) had persistent cytopenias and mild dysplasia; a low-grade myelodysplastic syndrome could not be ruled out, though del(7q) disappeared at 10-month and 4-month follow-up cytogenetic analyses, respectively. Two patients (cases #22 and 23) received an allogeneic stem cell transplantation (for the primary malignancy) at 1 and 4 months respectively, after the detection of del(7q), and no definitive diagnosis was rendered. Sixteen patients (cases 24–39), all with a small del(7q clone), showed no evidence of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms (no cytopenia, dysplasia or increased blasts) by the end of the follow-up period (Figure 1). The median follow-up was 38 months (range 1–117 months) for the patients without a diagnosis of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms.

In addition to the 12 patients who were diagnosed with therapy-related myeloid neoplasms at the same time as del(7q) detection, 6 additional patients were later diagnosed with therapy-related myeloid neoplasms (five therapy-related myelodysplastic syndromes, cases #13–17; one therapy-related chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, case #18) in follow-up bone marrow analyses with a median interval of 7 months (range: 3–48 months). Morphologically, when del(7q) was first detected, three of these patients (cases 13–15) showed mild dysplastic features and three showed no dyspoiesis (cases 16–18) in their bone marrow. When patients developed overt dysplasia and worsening cytopenia leading to the diagnosis of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, three patients (cases 13, 14 and 16) showed persistent isolated del(7q), two patients (cases 15 and 17) demonstrated clonal evolution, and one patient (case 18) showed new unrelated abnormal clones (listed above).

Of the 18 patients with an ultimate diagnosis of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, 7 patients with therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome (cases 1–3, 6, 11, 14 and 16) progressed to acute myeloid leukemia after a median of 10 months (range, 5–16 months). Nine patients (cases 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, 16 and 18) were treated with hypomethylating agents; five patients were treated with chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia (cases 1, 2, 3, 14 and 16); and six patients (cases 1, 3, 9, 11, 14 and 18) also underwent allogeneic stem cell transplant. Seven patients (cases 6, 7, 10, 12, 13, 15 and 17) received supportive therapy only (see Supplementary Material). At the time of last follow-up, 17/18 patients with therapy-related myeloid neoplasms had died with a median survival of 12 months after the therapy-related myeloid neoplasms were diagnosed, and only one patient (case 18) who received hypomethylating agent therapy followed by stem cell transplantation was alive in complete remission.

For the 21 patients who were not diagnosed with therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, 4 patients (cases 22, 23, 37 and 38) received an allogeneic stem cell transplant for the primary cancer and the other 17 patients did not receive any additional treatment regardless of the detection of del(7q). Seven patients (cases 25, 26, 29, 30, 32–34) had no indication for myeloid neoplasms and no follow-up bone marrow evaluation was done; eight patients (cases 20, 21, 24, 27, 28, 31, 35, 36) had undetectable del(7q) in the follow-up bone marrow and no indication for a secondary myeloid neoplasm; patient 19 was suspected to have a therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome and died 4 months later but no follow-up bone marrow was performed; patient 39 had del(7q) detected intermittently in 5–10% metaphases, and no indication for a myeloid neoplasm. By the end of follow-up, 6 patients died of their primary cancer or complications, 13 were alive with no evidence of primary cancer or therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, 1 was alive with primary cancer and 1 was lost to follow-up (Table 1).

Discussion

In this study, we describe 39 patients who acquired del(7q) as a sole abnormality in their bone marrow following cytotoxic chemotherapy/radiotherapy. Eighteen patients developed therapy-related myeloid neoplasms at the time del(7q) was detected (n=12) or during the follow-up interval (n=6); 16 patients showed no evidence of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms throughout the follow-up period; and 5 patients demonstrated cytopenia and/or dysplasia, but the diagnosis of a therapy-related myeloid neoplasm could not be established.

In this study, del(7q) clone size appears to be most closely correlated with the risk of developing therapy-related myeloid neoplasms. One can postulate that clone size detected by interphase FISH is more accurate compared with that by counting dividing cells (metaphase analysis). Our data show that the clone size detected by interphase FISH is proportional to, but overall smaller than, the percentage of abnormal metaphases identified by conventional chromosomal analysis. This is likely attributable to a gain of proliferative advantage of abnormal clones over normal cells in cell culture. Furthermore, interphase FISH analysis may be more accurate compared with conventional cytogenetics, since 200 cells are counted in interphase FISH analysis and only 20 metaphases are analyzed in conventional cytogenetics. Nevertheless, all 15 patients with del(7q) involving ≥40% metaphases corresponded to a morphological diagnosis of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, either at the time of del(7q) detection or in the subsequent bone marrow examination. In contrast, none of the patients with a small clone (<40% metaphases) were diagnosed with therapy-related myeloid neoplasms at the time of del(7q) detection. During follow-up, three patients with a small del(7q) clone developed therapy-related myeloid neoplasms: one patient (case 18) had two new unrelated clones that emerged after del(7q) became undetectable, and two patients (cases 15 and 17) showed clonal evolution and expansion of the del(7q) clone at the time the therapy-related myeloid neoplasm was diagnosed. These observations suggest that a small del(7q) clone is insufficient to result in therapy-related myeloid neoplasms; instead it may require additional factors like expansion of the del(7q) clone, clonal evolution or emergence of a new clone. These findings are similar to what we have observed previously,15, 16, 17 where a major/large clone is often associated with therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, whereas a minor/small clone may be clinically 'silent.' Interestingly, all patients with a large clone showed persistent del(7q) in the follow-up bone marrow, whereas del(7q) became undetectable in the follow-up bone marrow in 11 of 14 patients with a small clone. As ~10% of the patients with a small del(7q) clone ultimately developed a t-MN, continued surveillance of these patients with routine exams, CBCs and bone marrows is prudent to monitor expansion versus regression of the del(7q) abnormality.

Deletions of 7q are heterogeneous and the deleted regions can result in haploinsufficiency of different genes.18 Three commonly deleted regions in 7q have been identified, including commonly deleted region 1 (7q21–22), commonly deleted region 2 (7q34) and commonly deleted region 3 (7q35–36).11, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 Several genes on 7q have been considered as potential tumor suppressor genes and the loss of one or more of these genes could lead to development of a malignant myeloid neoplasm. SAMD9L, located on 7q21.3, plays a role in ERK signal transduction and haploinsufficiency of SAMD9L can result in sustained ERK activation and prolonged cell survival.18 SAMD9L-deficient mice exhibited pancytopenia and marked dysplasia resembling myelodysplastic syndromes.24 CUX1, located on 7q22, was expressed in haploinsufficient level in patients with myeloid malignancies involving del(7q),11 and the decreased expression of CUX1 contributed to tumorigenesis by activating the PI3K/Akt/mTOT pathway.25 MLL3, located on 7q36.1, might also be involved in the pathogenesis of myeloid malignancy; a 50% knockdown of MLL3 in murine lead to the development of myelodysplasia and leukemia.26 EZH2, located on 7q36.1, has been shown to be mutated in myeloid malignancies and portends high-risk disease.27, 28, 29 MLL5, located on 7q22.1, has been known to play a role in cell differentiation and self-renewal.30, 31, 32 In our cohort, all cases had at least one commonly deleted region deleted. 7q22 was the most commonly deleted region (in 38/39 of patients), which is consistent with other studies;33, 34 7q35–36 was the least commonly deleted region (in 18/39 of patients). 7q31 was also commonly deleted in our study as well as in other studies.34, 35 No significant difference in the deletions of common deleted regions among patients with or without therapy-related myelodysplastic syndromes was identified in our analysis.

In our cohort, patients with a history of solid tumors (cases 1–7, 12–13) seemed to be at a higher risk of developing therapy-related myeloid neoplasms related to large del(7q) clones, compared with patients who had a primary diagnosis of hematological malignancies. All nine patients with solid tumors in our cohort developed therapy-related myeloid neoplasms at the time of del(7q) detection or during follow-up, whereas three quarters of patients with hematological malignancies (lymphoma/myeloma/acute myeloid leukemia) did not. This is likely due to ascertainment bias; particularly a different clinical indication for bone marrow evaluation in patients with solid tumors versus in patients with a hematological malignancy. For patients with a primary diagnosis of a solid tumor, bone marrow analysis is not routinely performed after cytotoxic therapy unless patients develop persistent cytopenia(s). In contrary, bone marrow analysis is routinely performed as part of the treatment plan for patients with a hematological malignancy, regardless of the presence or absence of cytopenia(s) as part of ongoing surveillance. In other words, patients with solid tumors often had a higher suspicion for therapy-related myeloid neoplasms prior to bone marrow examination than patients with hematological malignancies. In addition, the therapeutic agents and doses used in solid tumors may be also associated with a higher risk of development of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms. It has been known that alkylating agents, topoisomerase II inhibitors, high intensity and combination regimens, combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy, are associated with a higher risk of development of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms.36

In summary, newly emerged isolated del(7q) in patients with prior cytotoxic therapies may not always indicate the presence or inevitable progression to therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, as only about half of the patients identified to have a del(7q) clone ultimately developed therapy-related myeloid neoplasms in our study. The risk of developing therapy-related myeloid neoplasms is closely correlated with the clone size of del(7q): a large clone appears to be tightly associated with developing therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, whereas a small clone often behaves as a clinically 'indolent' or a transient finding. Close follow-up and surveillance for clonal evolution or participation in an early intervention clinical trial may be most appropriate for patients with a minor del(7q) clone and a morphologically normal bone marrow.

References

Brunning RD, Orazi A, Germing U et al. Myelodysplastic syndromes/neoplasms, overview. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL et al. (eds). WHO Classification of Tumors of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. IARC: Lyon, France, 2008, pp 88–93.

Bejar R, Levine R, Ebert BL . Unraveling the molecular pathophysiology of myelodysplastic syndromes. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:504–515.

Preiss BS, Bergmann OJ, Friis LS et al. Cytogenetic findings in adult secondary acute myeloid leukemia (AML): frequency of favorable and adverse chromosomal aberrations do not differ from adult de novo AML. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 2010;202:108–122.

Hosono N, Makishima H, Jerez A et al. Recurrent genetic defects on chromosome 7q in myeloid neoplasms. Leukemia 2014;28:1348–1351.

Dohner H, Estey EH, Amadori S et al. Diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia in adults: recommendations from an international expert panel, on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood 2010;115:453–474.

Greenberg PL, Tuechler H, Schanz J et al. Revised international prognostic scoring system for myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 2012;120:2454–2465.

Ok CY, Hasserjian RP, Fox PS et al. Application of the international prognostic scoring system-revised in therapy-related myelodysplastic syndromes and oligoblastic acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2014;28:185–189.

Pedersen-Bjergaard J, Pedersen M, Roulston D et al. Different genetic pathways in leukemogenesis for patients presenting with therapy-related myelodysplasia and therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 1995;86:3542–3552.

Smith SM, Le Beau MM, Huo D et al. Clinical-cytogenetic associations in 306 patients with therapy-related myelodysplasia and myeloid leukemia: the University of Chicago series. Blood 2003;102:43–52.

Pedersen-Bjergaard J, Philip P, Larsen SO et al. Therapy-related myelodysplasia and acute myeloid leukemia. Cytogenetic characteristics of 115 consecutive cases and risk in seven cohorts of patients treated intensively for malignant diseases in the Copenhagen series. Leukemia 1993;7:1975–1986.

McNerney ME, Brown CD, Wang X et al. CUX1 is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 7 frequently inactivated in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2013;121:975–983.

Mauritzson N, Albin M, Rylander L et al. Pooled analysis of clinical and cytogenetic features in treatment-related and de novo adult acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes based on a consecutive series of 761 patients analyzed 1976-1993 and on 5098 unselected cases reported in the literature 1974-2001. Leukemia 2002;16:2366–2378.

Vardiman JW, Arber DA, Brunning RD et al. Therapy-related myeloid neoplasms. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL et al. (eds). WHO Classification of Tumors of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. IARC: Lyon, France, 2008, pp 88–93.

Shaffer LG, McGowan-Jordan J, Schmid M . An International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature (2013). Recommendations of the International Standing Committee on Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature. Basel: S Karger, 2013.

Tang G, Goswami RS, Liang CS et al. Isolated del(5q) in patients following therapies for various malignancies may not all be clinically significant. Am J Clin Pathol 2015;144:78–86.

Tang G, Wang SA, Lu V et al. Clinically silent clonal cytogenetic abnormalities arising in patients treated for lymphoid neoplasms. Leuk Res 2014;38:896–900.

Yin CC, Tang G, Lu G et al. Del(20q) in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a therapy-related abnormality involving lymphoid or myeloid cells. Mod Pathol 2015;28:1130–1137.

Honda H, Nagamachi A, Inaba T . -7/7q- syndrome in myeloid-lineage hematopoietic malignancies: attempts to understand this complex disease entity. Oncogene 2015;34:2413–2425.

Asou H, Matsui H, Ozaki Y et al. Identification of a common microdeletion cluster in 7q21.3 subband among patients with myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009;383:245–251.

Le Beau MM, Espinosa R, Davis EM et al. Cytogenetic and molecular delineation of a region of chromosome 7 commonly deleted in malignant myeloid diseases. Blood 1996;88:1930–1935.

De Weer A, Poppe B, Vergult S et al. Identification of two critically deleted regions within chromosome segment 7q35-q36 in EVI1 deregulated myeloid leukemia cell lines. PLoS One 2010;5:e8676.

Itzhar N, Dessen P, Toujani S et al. Chromosomal minimal critical regions in therapy-related leukemia appear different from those of de novo leukemia by high-resolution aCGH. PLoS One 2011;6:e16623.

Jerez A, Sugimoto Y, Makishima H et al. Loss of heterozygosity in 7q myeloid disorders: clinical associations and genomic pathogenesis. Blood 2012;119:6109–6117.

Nagamachi A, Matsui H, Asou H et al. Haploinsufficiency of SAMD9L, an endosome fusion facilitator, causes myeloid malignancies in mice mimicking human diseases with monosomy 7. Cancer Cell 2013;24:305–317.

Wong CC, Martincorena I, Rust AG et al. Inactivating CUX1 mutations promote tumorigenesis. Nat Genet 2014;46:33–38.

Chen C, Liu Y, Rappaport AR et al. MLL3 is a haploinsufficient 7q tumor suppressor in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell 2014;25:652–665.

Wang X, Dai H, Wang Q et al. EZH2 mutations are related to low blast percentage in bone marrow and -7/del(7q) in de novo acute myeloid leukemia. PLoS One 2013;8:e61341.

Ntziachristos P, Tsirigos A, Van Vlierberghe P et al. Genetic inactivation of the polycomb repressive complex 2 in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Med 2012;18:298–301.

Simon C, Chagraoui J, Krosl J et al. A key role for EZH2 and associated genes in mouse and human adult T-cell acute leukemia. Genes Dev 2012;26:651–656.

Heuser M, Yap DB, Leung M et al. Loss of MLL5 results in pleiotropic hematopoietic defects, reduced neutrophil immune function, and extreme sensitivity to DNA demethylation. Blood 2009;113:1432–1443.

Madan V, Madan B, Brykczynska U et al. Impaired function of primitive hematopoietic cells in mice lacking the Mixed-Lineage-Leukemia homolog MLL5. Blood 2009;113:1444–1454.

Zhang Y, Wong J, Klinger M et al. MLL5 contributes to hematopoietic stem cell fitness and homeostasis. Blood 2009;113:1455–1463.

Cordoba I, Gonzalez-Porras JR, Nomdedeu B et al. Better prognosis for patients with del(7q) than for patients with monosomy 7 in myelodysplastic syndrome. Cancer 2012;118:127–133.

Fischer K, Frohling S, Scherer SW et al. Molecular cytogenetic delineation of deletions and translocations involving chromosome band 7q22 in myeloid leukemias. Blood 1997;89:2036–2041.

Gonzalez MB, Gutierrez NC, Garcia JL et al. Heterogeneity of structural abnormalities in the 7q31.3 approximately q34 region in myeloid malignancies. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 2004;150:136–143.

Leone G, Fianchi L, Voso MT . Therapy-related myeloid neoplasms. Curr Opin Oncol 2011;23:672–680.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Modern Pathology website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goswami, R., Wang, S., DiNardo, C. et al. Newly emerged isolated Del(7q) in patients with prior cytotoxic therapies may not always be associated with therapy-related myeloid neoplasms. Mod Pathol 29, 727–734 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.67

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.67