Abstract

The assumption that intestinal metaplasia is a prerequisite for intraepithelial neoplasia/dysplasia and adenocarcinoma in the distal esophagus has been challenged by observations of adenocarcinoma without associated intestinal metaplasia. This study describes our experience of intestinal metaplasia in association with early Barrett neoplasia in distal esophagus and gastroesophageal junction. We reviewed the first endoscopic mucosal resection of 139 patients with biopsy-proven neoplasia. In index endoscopic mucosal resection, 110/139 (79%) cases showed intestinal metaplasia. Seven had intestinal metaplasia on prior biopsy specimens and three had intestinal metaplasia in subsequent specimens, totaling 120/139 (86%) patients showing intestinal metaplasia at some point supporting the theory of sampling error for absence of intestinal metaplasia in some cases. Those without intestinal metaplasia (13%) were enriched for higher stage disease (T1a Stolte m2 or above) supporting the assertion of obliteration of intestinal metaplasia by the advancing carcinoma. All cases of intraepithelial neoplasia and T1a Stolte m1 carcinomas had intestinal metaplasia (42/42). The average density of columnar-lined mucosa showing goblet cells was significantly less in shorter segments compared to those ≥3 cm (0.31 vs 0.51, P=0.0304). Cases where segments measured less than 1 cm were seen in a higher proportion of females and also tended to lack intestinal metaplasia. We conclude that early Barrett neoplasia is always associated with intestinal metaplasia; absence of intestinal metaplasia is attributable to sampling error or obliteration of residual intestinal metaplasia by neoplasia and those with segments less than 1 cm show atypical features for Barrett-related disease (absent intestinal metaplasia and female gender), supporting that gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinomas are heterogeneous.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Barrett esophagus is widely accepted to have a risk of progression to intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive adenocarcinoma. Most if not all published guidelines recommend commencing a program of surveillance with interval biopsies to detect early neoplasia. However, a globally accepted consensus for the diagnostic criteria of Barrett esophagus (and thus when to start and finish surveillance) has not been reached.

In the landmark paper of 1977, Paull et al1 published on the morphological heterogeneity of Barrett mucosa herein referred to as columnar-lined mucosa. They observed heterogeneity of the mucosa signified by three metaplastic mucosal types, namely gastric fundic-type mucosa, junctional-type mucosa, and villiform mucosa with columnar epithelium and intestinal-type goblet cells. Goblet cells were seen in greater density more proximally, an observation that has since been validated by several others.2, 3

The intestinalized epithelium or intestinal metaplasia, as it is also known, can be further characterized according to mucin histochemical and immunohistochemical expression,4 however these are not usually required for routine diagnosis, as the hematoxylin and eosin appearance of goblet cells is sufficient. Intestinal metaplasia is the only metaplastic change that has an established association with progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma.5, 6, 7 For this reason, some guidelines reserve the diagnosis of Barrett esophagus and endoscopic surveillance for only those lesions where intestinal metaplasia is histologically demonstrated.8, 9 Other guidelines, such as those of the British Society of Gastroenterology,10 would recommend surveillance on columnar-lined mucosa segments >3 cm in absence of histologic identification of intestinal metaplasia. They acknowledge the heterogeneity that is present in this mucosa and assume that an absence of intestinal metaplasia on biopsy is a sampling error. They also recommend surveillance on shorter segment columnar-lined mucosa conditional on the histologic identification of intestinal metaplasia. Australian Guidelines recommend that columnar-lined mucosa segments without intestinal metaplasia should have a repeat at 3–5 years and discharge from surveillance if still without intestinal metaplasia.11

Recently, there have been two conceptual challenges to the assumption that intestinal metaplasia is a fundamental intermediary of intraepithelial neoplasia and malignancy.

The first challenge is based on the work of Schmidt et al12 who proposed an alternative pathway of intraepithelial neoplasia. Brown et al13 built on this work, describing morphological and immunohistochemical features of the so called ‘non-adenomatous’ type, which is considered analogous to the foveolar type of gastric dysplasia. Brown et al also found a statistically significant association with the presence of non-adenomatous dysplasia and the absence of intestinal metaplasia in esophagectomy specimens and thus surmised that this observation might indicate the existence of an alternative pathway of carcinogenesis, independent of intestinal metaplasia.

A second challenge is from a Japanese and German collaborative group14, 15 who observe in endoscopic mucosal resection specimens that early stage and/or small adenocarcinoma were frequently adjacent to non-intestinalized columnar-lined mucosa only. They reason that early lesions are less likely to obliterate the mucosa from which they derive (a criticism of previous works) and propose that the frequent abutment of neoplasia with non-intestinalized mucosa is evidence of a pathway of carcinogenesis directly from the non-intestinalized metaplasia, independent of intestinal metaplasia.

Smith et al16 recently rebutted the assertion that early adenocarcinoma arises from non-intestinalized epithelium with support of their own findings from examining the specimens from 21 patients who had early adenocarcinoma on endoscopic mucosal resection. They found that despite intestinal metaplasia being absent in 37% of endoscopic mucosal resection specimens, all but one patient demonstrated evidence of intestinal metaplasia in a prior or subsequent specimen. In this paper, the authors specify that the intestinal metaplasia be defined by non-dysplastic columnar-lined epithelium that contains goblet cells, because of the theoretical possibility of new goblet cell phenotype expression in neoplastic tissue, independent of the surrounding non-neoplastic mucosa. They note that all patients had goblet cells identified in an endoscopic mucosal resection specimen if dysplastic mucosa is taken into consideration.

In our own experience, goblet cells are often identified in association with early neoplasia of the distal esophagus or gastroesophageal junction. This study was undertaken to confirm our impression that early neoplasia of the distal esophagus or gastroesophageal junction is virtually always associated with intestinal metaplasia in endoscopic mucosal resection specimens.

Materials and methods

The endoscopic mucosal resection specimens included in the study were those resected following a diagnosis of unequivocal glandular intraepithelial neoplasia or adenocarcinoma in biopsies of the distal esophagus or gastroesophageal junction from patients who attended Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, Western Australia, between 2006 and 2014. If multiple procedures were performed over time, only the first episode endoscopic mucosal resection specimen was included as the index specimen from each patient. Pathological features were tabulated for each case, including lesion type, stage, and Stolte classification. The Stolte system classifies the infiltration of early carcinomas (T1) as follows:17, 18

T1a

m1

Carcinoma limited to the lamina propria of the Barrett mucosa.

m2

Infiltration of the carcinoma into the newly formed (neo-) superficial/inner muscularis mucosae of the Barrett mucosa.

m3

Infiltration into the space between the superficial and deep layers of muscularis mucosae.

m4

Infiltration into the original (outer/deep) muscularis mucosae of the esophageal mucosa.

T1b

sm1

Infiltration into the upper third of the submucosa of the esophageal mucosa.

sm2

Infiltration into the middle third of the submucosa of the esophageal mucosa.

sm3

Infiltration into the lower third of the submucosa of the esophageal mucosa.

If intestinal metaplasia was absent on the index endoscopic mucosal resection specimen, previous and subsequent biopsies, endoscopic mucosal resections, and formal resections for that patient were examined to establish the historical presence or absence of intestinal metaplasia in each case. Endoscopic mucosal resection specimens that were diagnosed as stage T1 adenocarcinoma from Envoi Specialist Pathologists Laboratory (Queensland) were also reviewed to enrich the series with early stage adenocarcinoma.

Preparation and Examination of Endoscopic Mucosal Resection Specimens

Specimens obtained from endoscopic mucosal resection included tissue taken as a single piece or multiple pieces. All were fixed and serially sliced at 2–3 mm intervals and processed in entirety, using a standard protocol as previously described.18

Mucosal Assessment

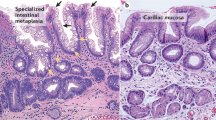

One or more of four investigators (BA, JB, IB, and MPK) performed morphological assessment of intestinal metaplasia by examining all slides from each tissue block of the entire endoscopic mucosal resection. Intestinal metaplasia was considered to be present when goblet cells were present in non-dysplastic columnar mucosa. Goblet cells were identified morphologically on hematoxylin and eosin stained slides as cells with a distended lightly hematoxylin stained vacuole and compressed basal nucleus with displacement of the membranes of adjacent cells (See Figures 1 and 2). All the lesions were confirmed to be either in the tubular esophagus or at the gastroesophageal junction (as defined by proximal extent of gastric folds) by the interventional endoscopist. Maximal segment length as measured on endoscopy was stratified by cases <1 cm and ≥1 cm in line with the recommendations of Shaheen et al.9

Columnar-lined mucosa with intramucosal carcinoma (T1a Stolte m1) that obliterates the superficial mucosa in continuity with residual foveolar-type glandular epithelium. There are underlying non-neoplastic glands and the inner layer of the duplicated muscularis mucosae is seen at the bottom of the image.

Semi-Quantitative Assessment

One or more of three investigators (BA, JB, and MPK) performed a semi-quantitative assessment of intestinal metaplasia on a subset of cases by examining representative slides from each tissue block of the entire endoscopic mucosal resection. Goblet cells were identified morphologically as described previously. The goblet cell presence was quantified by subdividing the columnar-lined mucosa into approximate 1 mm linear units as defined by one field of view of the Olympus DX40 microscope using a × 20 objective and eyepieces of field number 22 (calculated field of view diameter: 1.1 mm). Fields comprising columnar-lined mucosa with and without goblet cells were tallied at one level of each tissue block and calculated as a proportion of the total counted. Sub-squamous glands showing goblet cells were not tallied. Well-organized, native oxyntic-type mucosa likely to represent gastric fundus was not included in the assessment to ensure only columnar-lined mucosa of the esophagus was assessed. Areas where the type of surface epithelium was not identifiable due to orientation, denudation, or ulceration were not included.

Statistical Analysis

Means were compared using independent sample t-tests except for the semi-quantitative analysis where the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test was used. Proportions were compared using the Fisher exact test. All analysis was performed using SAS 9.4.

Results

Demographics

There were 139 patients overall, including 122 males and 17 females. The age range was 33–88 years old. The case distributions by highest stage lesion present at index endoscopic mucosal resection were 20 intraepithelial neoplasia only, 89 T1a and 30 T1b. The stratification of T1a cases by Stolte staging was 24 of m1, 41 of m2, 15 of m3, and 9 of m4. Table 1 also shows the endoscopic data that were available for 124/139 cases.

Characteristics of Cases with and without Intestinal Metaplasia on Index Endoscopic Mucosal Resection Specimen

One hundred and ten of 139 (79%) cases showed intestinal metaplasia on index endoscopic mucosal resection (Table 1). Exploring the procedural history of patients that did not show intestinal metaplasia, seven had documented intestinal metaplasia on prior biopsy specimens and three had intestinal metaplasia in subsequent specimens, thus totaling 120/139 (86%) patients showing intestinal metaplasia at some point if not the index endoscopic mucosal resection.

One hundred and twenty of 139 cases of early neoplasia defined by intraepithelial neoplasia (n=20) and T1 carcinomas (n=100) showed intestinal metaplasia. The 19 cases with no intestinal metaplasia were all T1 carcinomas, whereas all cases with intraepithelial neoplasia only showed goblet cells. Intestinal metaplasia was present in 95% (42/44) of index endoscopic mucosal resection for intraepithelial neoplasia and earliest stage carcinomas (T1a Stolte m1) considered together. Both cases that did not show intestinal metaplasia in the index endoscopic mucosal resection had shown intestinal metaplasia on a prior biopsy; therefore, 100% of intraepithelial neoplasia and early carcinomas up to Stole stage M1 were associated with intestinal metaplasia.

Cases that lacked intestinal metaplasia on index endoscopic mucosal resection were not only associated with a higher proportion of short segment columnar-lined mucosa (as defined as <1 cm) and also with more advanced stage (American Joint Committee on cancer tumor stage T1b).

Table 2 details the characteristics of the 19 cases that had no documented intestinal metaplasia on index endoscopic mucosal resection or historically. Seven of the 19 cases had subsequent formal resections with no intestinal metaplasia. Notwithstanding, patients lost to follow-up or cured by intervening procedures could represent some of the other cases.

Examining the features of these 19 cases (in two endoscopic data were not available), there was an enrichment of cases with short segment columnar-lined mucosa (as defined as <1 cm). Notably, there were only two cases with a columnar-lined mucosa segment >1 cm and only one of these with a segment >3 cm. The stage of disease in these cases were T1b and T1a Stolte m3.

Comparison of Cases by Endoscopic Measurement of Columnar-Lined Mucosa Segment

Endoscopic data were available in 124 cases. Nineteen of 124 (15%) lesions were at the gastroesophageal junction with a segment <1 cm in length or no columnar-lined mucosa segment identified on endoscopy. The group of cases with segments <1 cm had a significantly higher proportion of female patients (P=0.0004). Eight of 16 (50%) female cases had segment lengths <1 cm compared to 11/97 (10%) of male cases. Intestinal metaplasia was present in a significantly higher proportion among cases with segments ≥1 cm (P<0.0001) at 78%, compared to only 37% of cases with segments <1 cm. No significant difference in mean age was observed. Table 3 details the semi-quantitative analysis findings, where there was significantly less field units of columnar-lined mucosa available for examination in columnar-lined mucosa segments <3 cm (30.4 vs 109.0, P=0.0012), but also the proportion of goblet cell bearing field units were lower in the segments <3 cm (0.31 vs 0.51, P=0.0304), indicating a higher density of goblet cells in segments ≥3 cm.

Comparison of Cases by Stage

There were a significantly higher proportion of cases with intestinal metaplasia on index endoscopic mucosal resection at the earliest stages (intraepithelial neoplasia only and Stolte m1, see Table 4, P-value=0.0007). Cases with short segments were not significantly under represented (see Table 4, P-value=0.07). There was no significant difference in gender or mean age when cases were analyzed by stage.

Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to confirm that Barrett esophagus-related neoplasia is associated with intestinal metaplasia by analyzing dysplasia and early adenocarcinomas in a large cohort of endoscopic mucosal resections. Secondarily, we aimed to analyze any factors that could contribute to the absence of intestinal metaplasia in terms of a pathway of carcinogenesis independent of intestinal metaplasia or other factors such as sampling error. We demonstrated that 120/139 cases showed intestinal metaplasia. The 19 cases with no intestinal metaplasia were all invasive carcinomas, whereas all with intraepithelial neoplasia only showed intestinal metaplasia. Cases that lacked intestinal metaplasia on index endoscopic mucosal resection were associated with a significantly higher proportion of short segment columnar-lined mucosa (<1 cm) and also with higher stage disease.

We are of the opinion that higher stage lesions may obliterate the underlying non-neoplastic mucosa from which they developed. Our finding supports this view that all of the lowest stage cases (Stolte m1 or less) are associated with intestinal metaplasia. In contrast, the two cases with absent intestinal metaplasia that had columnar-lined mucosa 1 cm or longer had higher stage disease (see Table 2; T1b and T1a Stolte m3, respectively). With these assertions, it appears that all long segment Barrett-related neoplasia are likely to show intestinal metaplasia. We conclude that all Barrett-related neoplastic lesions in segments 1 cm or longer are associated with intestinal metaplasia based on the finding of intestinal metaplasia in 100% of intraepithelial neoplasia and Stolte m1 carcinomas.

When we further examined the characteristics of cases that showed segments <1 cm, we found higher proportions of cases that (1) lacked intestinal metaplasia and (2) female gender, which are both unusual trends compared to established trends of adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus associated with Barrett disease.19, 20 The possibility that these cases represent a different etiology or are cardia-based tumors growing into the gastroesophageal junction is a potential explanation. An in-depth study including a large series of these tumors is warranted.

Observations that intestinal metaplasia is detected later in the course of endoscopic surveillance in short segment columnar-lined mucosa compared to long is worth discussion.21 It could be that goblet cells become more dense the further the segment extends from the gastroesophageal junction, as it is well documented that goblet cells are most richly distributed in the proximal portions of a columnar-lined mucosa segment.1, 2, 3 We found the proportion of linear field units that contained goblet cells per case was significantly lower in columnar-lined mucosa <3 cm. Sampling bias for the detection of goblet cells in this group is mitigated by the fact that often times smaller segments are more completely sampled by an endoscopic mucosal resection procedure. This finding further supports a difference in distribution relative to either segment length or maximum distance from the gastroesophageal junction. Cotton et al22 have observed that dysplasia is also preferentially present in the proximal half of segments. There are a number of studies that find Barrett’s related dysplasia and early adenocarcinoma are more prevalent in the right hemisphere of the esophagus on a circumferential axis,23, 24, 25 but no studies describing the circumferential distribution of goblet cells have been identified.

Like Smith et al,16 we conclude that intestinal metaplasia accompanies virtually all glandular neoplasia arising in long segments of columnar-lined mucosa, excepting where the lesion may have obliterated the residual non-neoplastic mucosa. The scope of this study does not address the suitability of biopsy protocols to detect intestinal metaplasia in Barrett mucosa, or the minimum endoscopically measured length of segment that should be considered as Barrett mucosa. However, where we have observed neoplasia of the gastroesophageal junction in short segment or absent columnar-lined mucosa (cases falling short of accepted endoscopic criteria for Barrett esophagus), we report features that are not typical of Barrett-related neoplasia; including lack of intestinal metaplasia and a higher likelihood to be female; suggesting that some of these lesions may have a different origin or develop along a different pathway.

References

Paull A, Trier J, Dalton D et al. The histologic spectrum of Barrett’s esophagus. N Engl J Med 1976;295:476–480.

Theodorou D, Ayazi S, DeMeester SR et al. Intraluminal pH and goblet cell density in Barrett’s esophagus. J Gastrointest Surg 2012;16:469–474.

Chandrasoma PT, Der R, Dalton P et al. Distribution and significance of epithelial types in columnar-lined esophagus. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:1188–1193.

Piazuelo MB, Haque S, Delgado A et al. Phenotypic differences between esophageal and gastric intestinal metaplasia. Mod Pathol 2004;17:62–74.

Bhat S, Coleman HG, Yousef F et al. Risk of malignant progression in Barrett’s esophagus patients: results from a large population-based study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011;103:1049–1057.

Hvid-Jensen F, Pedersen L, Drewes AM et al. Incidence of adenocarcinoma among patients with Barrett’s esophagus. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1375–1383.

Bansal A, McGregor DH, Anand O et al. Presence or absence of intestinal metaplasia but not its burden is associated with prevalent high-grade dysplasia and cancer in Barrett’s esophagus. Dis Esophagus 2014;27:751–756.

Spechler SJ, Sharma P, Souza RF et al. American gastroenterological association medical position statement on the management of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology 2011;140:1084–1091.

Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;108:1238–1249.

Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, Ragunath K et al. British Society of Gastroenterology Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut 2014;63:7–42.

Whiteman DC, Appleyard M, Bahin FF et al. Australian clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus and early esophageal adenocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;30:804–820.

Schmidt HG, Riddell RH, Walther B et al. Dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 1985;110:145–152.

Brown IS, Whiteman DC, Lauwers GY . Foveolar type dysplasia in Barrett esophagus. Mod Pathol 2010;23:834–843.

Takubo K, Aida J, Naomoto Y et al. Cardiac rather than intestinal-type background in endoscopic resection specimens of minute Barrett adenocarcinoma. Hum Pathol 2009;40:65–74.

Aida J, Vieth M, Shepherd NA et al. Is carcinoma in columnar-lined esophagus always located adjacent to intestinal metaplasia ? A histopathologic assessment. Am J Surg Pathol 2015;39:188–196.

Smith J, Garcia A, Zhang R et al. Intestinal metaplasia is present in most if not all patients who have undergone endoscopic mucosal resection for esophageal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2016;40:537–543.

Vieth M, Stolte M . Pathology of early upper GI cancers. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2005;19:857–869.

Kumarasinghe MP, Brown I, Raftopoulos S et al. Standardised reporting protocol for endoscopic resection for Barrett oesophagus associated neoplasia: expert consensus recommendations. Pathology 2014;46:473–480.

Pohl H, Wrobel K, Bojarski C et al. Risk factors in the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:200–207.

Lepage Cô, Drouillard A, Jouve JL et al. Epidemiology and risk factors for oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Dig Liver Dis 2013;45:625–629.

Oberg S, Johansson J, Wenner J et al. Endoscopic surveillance of columnar-lined esophagus: frequency of intestinal metaplasia detection and impact of antireflux surgery. Ann Surg 2001;234:619–626.

Cotton CC, Duits LC, Wolf WA et al. Spatial predisposition of dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus segments: a pooled analysis of the SURF and AIM dysplasia trials. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:1412–1419.

Kariyawasam VC, Bourke MJ, Hourigan LF et al. Circumferential location predicts the risk of high-grade dysplasia and early adenocarcinoma in short-segment Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc 2012;75:938–944.

Enestvedt BK, Lugo R, Guarner-Argente C et al. Location, location, location: does early cancer in Barrett’s esophagus have a preference? Gastrointest Endosc 2013;78:462–467.

Ishimura N, Okada M, Mikami H et al. Pathophysiology of Barrett’s esophagus-associated neoplasia: circumferential spatial predilection. Digestion 2014;89:291–298.

Acknowledgements

Dr Allanson acknowledge the funding and support of the Nuovo-Soldati Foundation for Cancer Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Allanson, B., Bonavita, J., Mirzai, B. et al. Early Barrett esophagus-related neoplasia in segments 1 cm or longer is always associated with intestinal metaplasia. Mod Pathol 30, 1170–1176 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2017.36

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2017.36