Abstract

Arising from Grove, T. et al. Nature 459 694–697 (2009)10.1038/nature08044; Grove et al. reply

Global systematics in the location of volcanic arcs above subduction zones1,2 are widely considered to be a clue to the melting processes that occur at depth, and the locations of the arcs have often been explained in terms of the release of hydrous fluids near the top of the subducting slab (see, for example, refs 3–6). Grove et al.7 conclude that arc volcano location is controlled by melting in the mantle at temperatures above the water-saturated upper-mantle solidus and below the upper limit of stability of the mineral chlorite and in particular, that the arc fronts lie directly above the shallowest point of such melt regions in the mantle. Here we show that this conclusion is incorrect because the calculated arc locations of Grove et al.7 are in error owing to the inadequate spatial resolution of their numerical models, and because the agreement that they find between predicted and observed systematics arises from a spurious correlation between calculated arc location and slab dip. A more informative conclusion to draw from their experiments is that the limits of chlorite stability (figure 1b of ref. 7) cannot explain the global systematics in the depth to the slab beneath the sharply localized arc fronts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Grove et al.7 hypothesize that arc volcano location is controlled by melting in the mantle at pressure and temperature conditions defined as ‘P, Tmelt’ in their figure 1b. Grove et al.7 then use numerical models of subduction zones to predict arc location and its global systematics. They conclude that the agreement between their calculated systematics of arc location and observations of real subduction zones2,8 validates their hypothesis (figure 3 of ref. 7) but closer inspection of the shape of the P, Tmelt region casts doubt upon this conclusion. A characteristic feature of subduction-zone models9 is the narrow thermal boundary layer, sub-parallel to and just above the slab surface, which contains the temperature range of P, Tmelt (∼800–850 °C). For all but the slowest convergence rates, this boundary layer begins close to the depth at which the slab is viscously coupled to the wedge. Hence we should expect the region enclosing P, Tmelt to be a very thin, continuous layer above the slab, with its shallowest extent at an almost constant depth. The results of Grove et al.7 (green squares in their figure 2) are inconsistent with this expectation, and raise the suspicion of an error in their calculations.

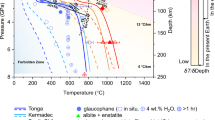

To locate their region of P, Tmelt, Grove et al.7 determined which nodes of their 2.3 × 2.3-km computational mesh lay within that P–T range. Because those conditions occur within a boundary layer only a few kilometres thick that is inclined at an angle to the mesh, this procedure did not resolve the full extent of the P, Tmelt region. To check their results, we calculated the temperature fields for subduction zones on a 1 × 1-km grid, then resampled it to both 2.3-km resolution and to 0.25-km resolution. This was done for a range of subduction parameters and for each calculation we determined the P, Tmelt region and its shallowest point. We found that at 2.3-km resolution, the minimum depth of P, Tmelt ranged between about 57 and 76 km, consistent with the range found by Grove et al.7. On the 0.25 × 0.25-km grid, however, the minimum depth was confined between 57 and 61 km (Fig. 1a), consistent with the expectations we describe in the preceding paragraph. At either resolution, the minimum depth of P, Tmelt is independent of the slab dip and of the convergence rate.

a, Calculated depth Dmelt of the shallowest portion of the P, Tmelt-based melting field (compare figures 1 and 2 of ref. 7). Calculations were carried out on a 1-km finite-volume mesh9, for dip of 30° to 70° in steps of 10°, and for convergence rate V from 30 to 100 mm yr−1, in steps of 10 mm yr−1; these ranges include the parameters of the calculations of ref. 7. The points correspond to the minimum depths of melting calculated according to the hypothesis and methods of Grove et al.7 for a 2.3 × 2.3-km resampled grid (open triangles) and for a 0.25 × 0.25-km resampled grid (filled triangles). b, Diamonds show the depth of the slab Dslab, determined seismologically2 (error bars as described by ref. 2); filled triangles show the calculated Dslab below the locus of shallowest melting, for the 0.25 × 0.25-km resampled grid from panel a. The red triangles correspond to the corrected values of Dslab for the combinations of dip and convergence rate used by ref. 7 (T. Grove et al., personal communication). The grey line corresponds to a constant Dslab = 62 km. c, This panel corresponds to the lower 200 km of figure 3 in ref. 7. Points as for panel b, plotted for the horizontal distance between the trench and the arc, which is equal to Dslab/tan(Dip), the quantity on the y axis of figure 3 of ref. 7. The grey line corresponds to Dslab = 62 km and demonstrates the spurious correlation referred to in the main text.

Grove et al.7 compare their calculations with seismic studies, which show that the depth of the slab beneath arcs varies between ∼80 and ∼150 km (refs 2, 8) and has a negative correlation with the descent speed of the slab (Fig. 1b). The depth to the top of the slab predicted by the hypothesis of Grove et al.7 applied under our recalculations is ∼60–75 km, independent of dip or convergence rate (Fig. 1b), and thus does not agree with the observations.

The agreement between model and observations in Grove et al.7 is spurious, and is the result of their choice of variables. Figure 1c recreates their figure 3, which shows the apparent consistency between model and observations, using our recalculated location of arcs. The sine of slab dip is plotted on the x axis, and on the y axis is the arc–trench distance, which for all points (calculated and observed; see table 1 in ref. 7) is taken as the depth of the slab divided by the tangent of the dip. The presence of the sine of the dip on each axis ensures a spurious correlation; this is illustrated clearly in Fig. 1c by the grey line that corresponds to a constant value of the depth of the slab, Dslab = 62 km.

Therefore there is no significance in the match between models and observations reported by Grove et al.7, and their conclusion that “the kinematic control on the location of mantle melting is primarily slab dip” (page 696 of ref. 7) is mistaken. Instead, we conclude from their experiments that the limits of chlorite stability (figure 1b of ref. 7) cannot explain the global systematics in the depth of the slab beneath sharply localized arc fronts, which is true for any strongly temperature-dependent process that takes place near the top of the slab, as we have discussed. In ref. 10 we suggest a process that can account for the global systematics in location of the arcs.

References

Tovish, A. & Schubert, G. Island arc curvature, velocity of convergence and angle of subduction. Geophys. Res. Lett. 5, 329–332 (1978)

England, P., Engdahl, R. & Thatcher, W. Systematic variation in the depths of slabs beneath arc volcanoes. Geophys. J. Int. 156, 377–408 (2004)

Gill, J. Orogenic Andesites and Plate Tectonics (Springer, 1981)

Tatsumi, Y. & Eggins, S. Subduction Zone Magmatism (Blackwell Science, 1995)

Iwamori, H. Transportation of H2O and melting in subduction zones. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 160, 65–80 (1998)

Tatsumi, Y. The subduction factory: how it operates in the evolving Earth. GSA Today 15, 4–10 (2005)

Grove, T., Till, C., Lev, E., Chatterjee, N. & Medard, E. Kinematic variables and water transport control the formation and location of arc volcanoes. Nature 459 694–697 (2009) erratum 460, 1044 (2009)

Syracuse, E. & Abers, G. Global compilation of variations in slab depth beneath arc volcanoes and implications. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 7 Q05017 10.1029/2005GC001045 (2006)

van Keken, P. et al. A community benchmark for subduction zone modeling. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 171, 187–197 (2008)

England, P. C. & Katz, R. F. Melting above the anhydrous solidus controls the location of volcanic arcs. Nature 467, 700–703 (2010)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Competing financial interests: declared none.

PowerPoint slides

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

England, P., Katz, R. Global systematics of arc volcano position. Nature 468, E6–E7 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09154

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09154

This article is cited by

-

Grove et al. reply

Nature (2010)