Abstract

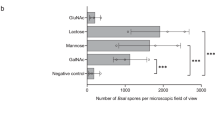

The recent arrival of Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans in Europe was followed by rapid expansion of its geographical distribution and host range, confirming the unprecedented threat that this chytrid fungus poses to western Palaearctic amphibians1,2. Mitigating this hazard requires a thorough understanding of the pathogen’s disease ecology that is driving the extinction process. Here, we monitored infection, disease and host population dynamics in a Belgian fire salamander (Salamandra salamandra) population for two years immediately after the first signs of infection. We show that arrival of this chytrid is associated with rapid population collapse without any sign of recovery, largely due to lack of increased resistance in the surviving salamanders and a demographic shift that prevents compensation for mortality. The pathogen adopts a dual transmission strategy, with environmentally resistant non-motile spores in addition to the motile spores identified in its sister species B. dendrobatidis. The fungus retains its virulence not only in water and soil, but also in anurans and less susceptible urodelan species that function as infection reservoirs. The combined characteristics of the disease ecology suggest that further expansion of this fungus will behave as a ‘perfect storm’ that is able to rapidly extirpate highly susceptible salamander populations across Europe.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Martel, A. et al. Wildlife disease. Recent introduction of a chytrid fungus endangers Western Palearctic salamanders. Science 346, 630–631 (2014)

Spitzen-van der Sluijs, A . et al. Expanding distribution of lethal amphibian fungus Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans in Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 22, 1286–1288 (2016)

Fisher, M. C. et al. Emerging fungal threats to animal, plant and ecosystem health. Nature 484, 186–194 (2012)

Martel, A. et al. Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans sp. nov. causes lethal chytridiomycosis in amphibians. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 15325–15329 (2013)

Cheng, T. L., Rovito, S. M., Wake, D. B. & Vredenburg, V. T. Coincident mass extirpation of neotropical amphibians with the emergence of the infectious fungal pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 9502–9507 (2011)

Kim, K . & Harvell, C. D. The rise and fall of a six-year coral-fungal epizootic. Am. Nat. 164 (Suppl 5), S52–S63 (2004)

Frick, W. F. et al. An emerging disease causes regional population collapse of a common North American bat species. Science 329, 679–682 (2010)

Gross, A., Holdenrieder, O., Pautasso, M., Queloz, V. & Sieber, T. N. Hymenoscyphus pseudoalbidus, the causal agent of European ash dieback. Mol. Plant Pathol. 15, 5–21 (2014)

Garner, T. W. J. et al. Mitigating amphibian chytridiomycosis in nature. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 317, 20160207 (2016)

Spitzen-van der Sluijs, A . et al. Rapid enigmatic decline drives the fire salamander (Salamandra salamandra) to the edge of extinction in the Netherlands. Amph. Rept. 34, 233–239 (2013)

McMahon, T. A. et al. Amphibians acquire resistance to live and dead fungus overcoming fungal immunosuppression. Nature 511, 224–227 (2014)

Muths, E., Scherer, R. D. & Pilliod, S. D. Compensatory effects of recruitment and survival when amphibian populations are perturbed by disease. J. Appl. Ecol. 48, 873–879 (2011)

Schmidt, B. R., Feldmann, R. & Schaub, M. Demographic processes underlying population growth and decline in Salamandra salamandra. Conserv. Biol. 19, 1149–1156 (2005)

Seifert, D. Untersuchungen an einer ostthüringischen Population des Feuersalamanders (Salamandra salamandra). Artenschutzreport 1, 1–16 (1991)

Rosenblum, E. B., Voyles, J., Poorten, T. J. & Stajich, J. E. The deadly chytrid fungus: a story of an emerging pathogen. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000550 (2010)

Sabino-Pinto, J. et al. First detection of the emerging fungal pathogen Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans in Germany. Amph. Rept. 36, 411–416 (2015)

Yap, T. A., Koo, M. S., Ambrose, R. F., Wake, D. B. & Vredenburg, V. T. Biodiversity. Averting a North American biodiversity crisis. Science 349, 481–482 (2015)

Price, S. J., Garner, T. W. J., Cunningham, A. A., Langton, T. E. S. & Nichols, R. A. Reconstructing the emergence of a lethal infectious disease of wildlife supports a key role for spread through translocations by humans. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 283, 20160952 (2016)

Blooi, M. et al. Duplex real-time PCR for rapid simultaneous detection of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis and Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans in Amphibian samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51, 4173–4177 (2013)

Blooi, M. et al. Correction for Blooi et al., Duplex real-time PCR for rapid simultaneous detection of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis and Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans in Amphibian samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 54, 246 (2016)

Mao, J., Hedrick, R. P. & Chinchar, V. G. Molecular characterization, sequence analysis, and taxonomic position of newly isolated fish iridoviruses. Virology 229, 212–220 (1997)

Williams, B. K., Nichols, J. D. & Conroy, M. J. Analysis and management of animal populations. (Academic Press, 2002)

Lebreton, J. D., Nichols, J. D., Barker, R. J., Pradel, R. & Spendelow, J. A. Modeling individual animal histories with multistate capture–recapture models. Adv. Ecol. Res. 41, 87–173 (2009)

Kéry, M. & Schaub, M. Bayesian population analyzing using WinBUGS – a hierarchical perspective (Academic Press, 2012)

Plummer, M. JAGS: a program for analyzing of Bayesian graphical models using Gibbs sampling. In Proc. 3rd International Workshop on Distributed Statistical Computing ( Hornik, K ., Leisch, F. & Zeileis, A., 2003)

Blooi, M. et al. Treatment of urodelans based on temperature dependent infection dynamics of Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans. Sci. Rep. 5, 8037 (2015)

Schmeller, D. S. et al. Microscopic aquatic predators strongly affect infection dynamics of a globally emerged pathogen. Curr. Biol. 24, 176–180 (2014)

Dail, D. & Madsen, L. Models for estimating abundance from repeated counts of an open metapopulation. Biometrics 67, 577–587 (2011)

Acknowledgements

The technical assistance of M. Claeys and M. Couvreur is appreciated. K. Roelants kindly provided the artwork. This research is supported by Ghent University Special research fund (GOA 01G02416 and BOF01J030313) and by the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) (G007016N, FWO16/PDO/019, FWO12/ASP/210).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M., G.S. and F.P. designed the research. A.M., G.S., L.O.R., S.V.P., F.P., C.A., A.L., T.K. and W.B. carried out the research. A.M., F.P., G.S., S.C., B.R.S., M.S., L.O.R. and F.H. analysed the data. A.M., F.B., G.S., B.R.S. and F.P. wrote the paper with input from all other authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Reviewer Information Nature thanks A. Dobson, M. Fisher and B. Han for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

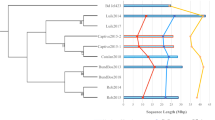

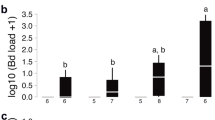

Extended Data Figure 1 B. salamandrivorans GE loads in soil.

To investigate whether B. salamandrivorans can be detected in terrestrial environments, soil samples were taken in the close vicinity of experimentally infected animals (experimental samples) and naturally infected salamanders in the Robertville outbreak area (outbreak samples). Error bars depict s.d.

Extended Data Figure 2 B. salamandrivorans GE loads detection in experimentally infected soil, incubated at 4 °C and 15 °C.

Error bars depict s.d.

Supplementary information

In vitro culture of Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans cultured in TghL broth at 15°C

A sporulating zoosporangium, motile spores and floating encysted spores are shown at 400x magnification. This video was recorded through an Olympus IX50 inverted microscope using a videocapture plugin in ImageJ. (MP4 5759 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stegen, G., Pasmans, F., Schmidt, B. et al. Drivers of salamander extirpation mediated by Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans. Nature 544, 353–356 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature22059

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature22059

This article is cited by

-

Localized transmission of an aquatic pathogen drives hidden epidemics and population collapse in a terrestrial host

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2026)

-

A novel amphibian herpesvirus (candidate Batravirus ranidallo5) associated with disease in free-ranging Iberian painted frogs (Discoglossus galganoi) in Spain

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Near-infrared spectroscopy as a diagnostic screening tool for lethal chytrid fungus in eastern newts

Communications Biology (2025)

-

RCA 1-binding glycans as a marker of Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans infection intensity at early stages of pathogenesis

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Pathogens and planetary change

Nature Reviews Biodiversity (2025)

Majid Ali

Fungal Pathogens and oxyphile - oxyphobe conflicts

Stegen et. al. show a collapse without recovery of a Belgian population of fire salamander (Salamandra salamandra) with arrival of fungus Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans. (ref. 1) In the combined characteristics of the fungal disease ecology, they see the potential of a 'perfect storm' in which it is likely to rapidly extirpate susceptible salamander populations across Europe. Without an available option, they recognize ex-situ conservation as the only viable alternative. For the United States and other regions currently considered to be free of the fungus, prevention of introduction must be based on a clear understanding of the host-pathogen dynamics as well as availability of resistant or less susceptible reservoir host species for the pathogen.

This writer recognizes the relevance and importance of the Stegen paper to the work of physicians. Fungal epidemics usually do not hold public interest for long. This has been so as well with medical practitioners who are clinically involved with fungal pathogens. This seems odd since physicians, by and large, do recognize important clinical differences between fungal and non-fungal infections. Historically, much was learned from non-fungal epidemics and some inferences could have been drawn concerning human disease from the past fungal epidemics involving bees, bats, and butterflies. Specifically, the examples of well-publicized large scale destructions of species include mass destruction of bats (with the white-nose syndrome caused by the fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans, ref. 2), honey bees (collapsing colony disease caused by Nosema ceranae, ref. 3), and large scale disappearance of Monarch butterflies (by mycorrhizal fungi, ref. 4). Now Stegen and colleagues reveal a much deeper dimension of fungal pathogens. They also point out that the same fate of American salamander species may be expected when the fungus is introduced to the country. For these and other reasons, in this writer's view the Stegen paper raises important questions not only about damage inflicted by fungal pathogens in the wild but also for humans.

Chytridiomycota are aquatic fungi that also thrive in the capillary network around soil particles. They are notable for their: (1) pathogenicity for amphibians; and (2) inhibition by amphibian cutaneous flora. However, this defense, as shown by Stegen et. al., does not protect fire salamander from Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans. The matter of such protection by the cutaneous flora of some amphibian species should be of interest to clinicians in considerations of host resistance.

In Altered States of Bowel Ecology (1980), (ref. 5), this writer addressed the matter of systemic symptom-complexes which clinically respond to measures that reduce the total load of fungal species in the gut flora. That led to his interest in gut immunopathology and studies of IgE antibodies in tissues and IgG antibodies in the blood with specificity for fungal antigen. (ref.6,7) This work and his parallel interest in the molecular biology of oxygen, (ref.8-9) led him to questions concerning host-pathogen dynamics among oxygen-consuming human cells (?oxyphiles) and oxygen-shunning fungal organisms in human ecosystems (oxyphobes?).(ref.10,11) These 'oxyphile-oxyphobe conflicts' - it seemed to him - represent a different dimension of clinical mycology that is ecologically oriented, bioenergetically directed, and therapeutically mindful of the influence of prevailing oxygen and oxygen-related conditions in the body ecosystems, especially those of the gut, blood, and liver. (ref. 9-11)

The recent report of incremental loss of oxygen from oceans (ref.12) is noteworthy in this context and so are the incremental oxidizing capacity of the planet Earth and the cumulative chemical load on its the ecosyetems. (ref.13) Might these factors be of importance in considerations of immunosuppression in our species? If so, might the matters of oxyphil-oxyphobe conflicts be clinically significant in the prevention and treatment of fungal overload and infections? Should physicians not think ecologically? Should they not be mindful of the state of oxygen homeostasis in their patients for health preservation and disease prevention?

The work of Stegen et al. is clearly of relevance to physicians' work.

References

1. Stegen G, Pasman F, Schmidt BR, et al. Drivers of salamander extirpation mediated by Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans. Nature. 2017;544:353.

2. Stone, WB. Bat white-nose syndrome: An emerging fungal pathogen. Science. 2009;323:227.

3. Higes M, Martin R, Meana A. Nosema ceranae, a new microsporidian parasite in honeybees in Europe. J Invert Pathol. 2006;92:93?95.

4. Lef�vre T, Oliver L, Hunter MD, et al. Evidence for trans- generatilonal medication in nature. 2010;13:1485-1493.

5. Ali M. Altered States of Bowel Ecology. (monograph). Teaneck, NJ, 1980.

6. Ali Ali M, Mesa -Tejada R, Fayemi AO, Nalebuff DJ, Connell JT: Localization of IgE in tissues by an immunoperoxidase technique. Arch Pathol Lab Med, 103:274-275, 1979.

7. Ali M. Ramanarayanan MP, Nalebuff DJ, Fadal RG, Willoughby JW: Serum concentrations of allergen-specific IgG antibodies in inhalant allergy: effect of specific immunotherapy. Am J Clin Pathol, 80:290-299, 1983.

8. Ali M. Respiratory-to-Fermentative (RTF) Shift in ATP Production in Chronic Energy Deficit States. Townsend Letter for Doctors and Patients. 2004;253:64-65.?

9. Ali M. Succinate Retention: The Core Krebs Dysfunction in Immune-Inflammatory Disorders. Townsend Letter. 2015;388:84-85. Succinate retention.

10. Ali M. Darwin, Dysox, and Disease. Volume XI. 3rd. Edi. The Principles and Practice of Integrative Medicine.2008. New York. (2009) Institute of Integrative Medicine Press.

11. Ali M. Darwin, Dysox, and Integrative Protocols. Volume XII. The Principles and Practice of Integrative Medicine. New York (2009). Institute of Integrative Medicine Press.

12. Schmidtko S, Stramma L, Visbeck M. Decline in global oceanic oxygen content. Nature 20117;543:335-339.

13. Gupta ML, Perturbation to global tropospheric oxidizing capacity due to latitudinal redistribution of surface sources of NOx, CH4 and CO. Geographical Research Letters. 1998;25:3931-3934.