Abstract

Aims:

To produce new lung age equations using four previously published predictive equations for forced expiratory volume in 1 second and to compare them with lung age equations published in 1985 and 2010.

Methods:

Initial comparisons used phantom subjects of different ages and levels of lung function. Comparison of lung age equations by regression analysis used an independent dataset of 3,206 randomly selected community-dwelling adults aged ≥18 years in the North West Adelaide Health Study.

Results:

The more recent equations estimated lung age as greater than chronological age as lung function decreased, whereas the oldest equations estimated lung age as less than chronological age until lung function was severely limited. Significant differences (p<0.001) were detected by regression analysis, with four newer lung age equations being significantly different from the 1985 equation and one being no different.

Conclusions:

Lung age estimates using six predictive equations spanning 50 years show differences attributable to cohort and period effects. This reinforces the need for regular updating of predictive equations for lung function. These results further confirm the need to use modern lung age equations which will provide a stronger message in smoking cessation counselling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Smoking cessation remains the most important intervention in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and can slow the progression of the disease. It will also have a positive effect on other diseases caused by smoking including heart disease, stroke, and cancers. Patient education to encourage smoking cessation can include providing spirometry results as ‘lung age’ (the age of a healthy never-smoker with the same result).1 Lung age may be more easily understood by patients than the standard methods of expressing lung function (L/s or percentage predicted) and can be depicted graphically to further aid understanding.2–4

Lung age is available as a smoking cessation tool on many modern spirometers, as an iPhone ‘App’, and can be calculated using tools available on the internet. It is easily applied in the primary care setting, but the concept remains controversial. The ongoing debate has valid points on both sides: it is supported by researchers interested in increasing smoking cessation rates,5,6 while those against claim that it is unscientific to blame low forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) results on damage caused by tobacco smoking alone as many factors influence these values.7

The application of lung age in recent research has been inconsistent (the ‘Get PHIT’ trial applied lung age when FEV1 was <80% predicted8 while the ‘Step2Quit’ trial communicated lung age when it was greater than actual age3) and consequently results have been varied; only the ‘Step2Quit’ trial has shown significantly higher quit rates in the intervention group than in the control group.3

To date, researchers have used the lung age equations produced by Morris and Temple in the USA in 1985.1 The predictive equations informing the lung age concept were published in 1971, almost 15 years earlier.9 Recently, research using a workplace dataset showed that the Morris lung age equations estimated lung age to be 20 years less than that estimated using Australian lung age equations produced by Newbury et al. in 2010.10 Of greater concern is that, in the smoker subgroup, the mean lung age estimated by the Morris equations was 12 years lower than the mean chronological age, indicating a ‘protective’ effect of tobacco smoking. These interesting results can most likely be attributed to the 40-year gap in data collection for the predictive equations, as well as sample differences.

The comparison of the Australian and Morris lung age equations was limited to male subjects in a workplace dataset.10 A more rigorous approach for further comparisons should involve community-based randomly selected subjects of both sexes. A broader comparison involving other lung age equations is also warranted. The aims of this current research are (1) to produce lung age equations using selected published spirometric predictive equations for FEV1 from different countries or continents by applying the Morris and Temple1 method of resolving the predictive equation for age; and (2) to compare these with the two previously compared lung age equations1,10 using a dataset of randomly selected independent community-based participants comprising both males and females.

Methods

Four predictive equations for FEV1 were selected for conversion to lung age equations in addition to the two previously published lung age equations,1,10 making a total of six for further comparison. The equations selected were for Caucasian adults and were amenable to re-solving according to the method used by Morris and Temple in 1985.1 The selected equations were:

-

Equations developed for the European Community for Steel and Coal (ECSC)11 and adopted by the European Respiratory Society (ERS) in 1993.12 These are from a similar era to those of Morris et al.9 and are still widely used in the UK and Europe.13

-

Equations developed for the USA in 1999 using the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III).14 These are currently recommended for use in the USA by the American Thoracic Society (ATS).

-

Equations from the Health Survey for England from 1995–6.15

-

Equations developed in Australia using a randomly selected sample from Adelaide, South Australia, 1995.16

The selected equations give newer alternatives for the USA and the UK, a large randomly selected alternative for Australia, as well as including European equations in common use.

As lung age is directly calculated from FEV1, initial comparisons of all six predictive equations involved calculation of predicted values for FEV1 using a range of male and female ‘phantom’ subjects of three different heights and an age range of 25–75 years.

The four selected predictive equations for FEV112,14–16 were then re-solved for age using the methods of Morris and Temple,1 creating four new lung age equations. Together with the equations of Morris and Temple1 and Newbury et al.,10 these were then compared using examples at 40 and 55 years of age and of average height: two men (178cm) and two women (165cm) with decreasing FEV1 values. 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) of lung age estimates were calculated using 1.967xStandard Error of the Estimate (SEE) of the original equation.

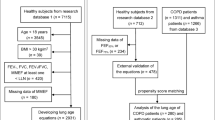

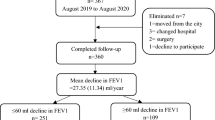

The six lung age equations were then compared using the North West Adelaide Health Study (NWAHS) dataset. NWAHS is a longitudinal study of a randomly selected sample of the population from the northern and western region of Adelaide, South Australia, who were aged >18 years at the time of recruitment.17,18 Recruitment commenced in 2000 and the stage 2 follow-up was in 2004–6. All participants were weighted according to the NWAHS guidelines prior to analysis using the stage 2 weighting variable which takes into account the age, sex, and probability of selection within the household, thus making the sample population representative of north-west Adelaide.

All lung age estimates using the NWAHS dataset were first compared by plotting lung age against actual age at the clinic visit for each participant, separately for males and females and separately for smoking status (current or healthy never smokers). Healthy never smokers were defined as those with no self-reported prior diagnosis of respiratory disease (chronic bronchitis, asthma or emphysema); smoking status was self-reported.

Regression analysis was then performed to compare all six lung age equations using the NWAHS stage 2 dataset for adults aged 25–75 years, males and females separately. The full regression model considered all main effects, two-way interactions, and the three-way interaction between age, group (i.e. source of prediction equation) and smoking status (current or healthy never smokers). Regression analysis was performed using the statistics package ‘R: A language and environment for statistical computing’, Version 2.12.2.

Ethics approval for the NWAHS project was given by the North West Adelaide Health Service Ethics of Human Research Committee. As de-identified data were used for this current research, no further ethics approval was necessary.

Results

Table 1 lists all lung age equations used in this comparison, with selected details of original data collection including country of origin and type of spirometer used. There is a large spread in the dates of data collection and a large range of equipment use.

Comparisons of FEV1 (predicted)

FEV1 values predicted by each of the six equations are shown in Figure 1 using phantom subjects of height 168cm (females) and 178cm (males). Across the age range of 25–75 years, the oldest equation predicted the lowest values across all ages and heights, the newest equation predicted the highest values, with all other equations predicting between these two. Differences in the linear and quadratic equations were also seen. Similar results were obtained at other heights for both males (172cm and 184cm) and females (155cm and 175cm) (data not shown).

Predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) with each of the selected equations in (A) females (height 168cm) and (B) males (height 178cm) using phantom subjects aged 25-75 years. The NHANES III and I Falaschetti results are curved due to their quadratic form. The highest values belong to the newest equations and the lowest values belong to the oldest equations, which illustrates the cohort and period effects.

Comparisons using phantom subjects

Similarly, a wide spread in lung age estimates was evident when the six lung age equations were applied to phantom subjects aged 40 and 55 years. Table 2 shows lung age estimates with 95% confidence intervals for a man of 178cm and a woman of 165cm. Decreasing lung function was simulated with lower FEV1 values at each height. The newest equation10 closely predicted the actual age for the male subject at 40 years of age (FEV1 4.5L) and also at 55 years of age (FEV1 4.0L). This was also the case for the female subjects (FEV1 3.2L at 40 years of age and 2.8L at 55 years of age). At these values, the other equations all predicted lung age as lower than actual age, again with the oldest equations (Morris and ECSC/ERS) predicting approximately 15–20 years ‘younger’. As FEV1 falls, lung age estimates increased, but the differences seen between equations remained similar for men. For 55-year-old females the differences in lung age estimates between equations became less as the FEV1 fell, but the results were otherwise similar to those of the males. The predictive equations that were quadratic in form14,15 were not able to perform lung age estimates in some lower age (25–30 years)/lower height combinations, more often in females than in males, due to mathematical constraints, in particular the inability to calculate the square root of a negative number (data not shown).

Comparisons using NWAHS

Initial comparisons of all six lung age equations using the NWAHS stage 2 dataset used scatter plots of chronological age plotted against lung age for males (469 healthy never smokers, 306 current smokers) and for females (511 healthy never smokers, 261 current smokers). These showed enough apparent differences between the current smoker group and the never smoker group to warrant investigation by regression analysis.

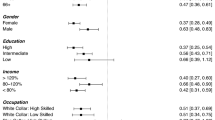

In the regression analysis the final fitted model was the same for males and females. These results are shown graphically in Figure 2, with the regression equations given in Table 3. At any age there were different intercepts with the y-axis, and different slopes for current smokers and healthy never smokers within each equation group. At older ages the lung age was significantly greater in the smoking group than in the never smoking group, and this was true within each equation group.

Best line of fit for each smoking subgroup for each equation in (A) females and (B) males. The final model equation included the main effect of Group (i.e. equation source) and the main effect of Smoking, which together define the intercept for our predicted model. The terms that include Age define the slope in our final fitted model. The main effect of Age and the two-way interactions between Age/Group and Age/Smoking were statistically significant at the 5% level.

For males, only the Morris and the ECSC/ERS (Quanjer) equations were similar (intercept p=0.20, slope p=0.27). The intercepts for the other four equations (Gore, NHANES III (Hankinson), Falaschetti, and Newbury) were all significantly different from the Morris equations at the p=0.001 level. Of all the equations, only the slope of the Falaschetti equation was statistically different from that of Morris (p<0.001), possibly due to the quadratic form of the original equation.

For females, all intercepts were significantly different from the Morris equation (p<0.001). The slopes of both the Gore and the ECSC/ERS equations were similar to that of the Morris equation (p=0.6 and p=0.54, respectively), while the NHANES III (p=0.008), Newbury (p<0.001), and Falaschetti (p<0.001) equations were all significantly different from that of Morris. Paradoxically, lung age estimates appeared higher in never smokers than in current smokers in younger females.

For both males and females, the effect of smoking was significant for all equation groups for both the intercept (p<0.001) and the slope (p<0.001). Given the absence of a Group/Smoking or a Group/Smoking/Age interaction, the contribution of smoking was the same for each of the six equation groups. Lung age for some equation groups increased at a faster rate than other groups.

Discussion

Main findings

This study illustrates large differences in the predicted FEV1 between the six predictive equations compared. This selection of equations spans almost 50 years of data collection, with the oldest equations predating the first guidelines for spirometry in 1979.19 New lung age equations based on these predictive equations for FEV1 demonstrate that the spread in predicted values for FEV1 then leads to a large difference in lung age estimations.

Our regression analysis using a large community-based dataset of randomly selected adults confirms that lung age estimates increase more with age in current smokers than in healthy never smokers, which suggests a dose-related response to tobacco smoke exposure. Further, it is evident that lung age equations developed from more recently produced predictive equations give lung age estimates that are significantly greater in both males and females than those of Morris and Temple.1

Both the cohort and the period effects relate to differences in subjects, the equipment used, and the standards applied across time.20,21 The cohort effect describes differences in lung function seen across generations that are linked to increases in stature due to improved health and better nutrition. The period effect reflects changes in equipment and technology (e.g. computerisation) as well as the introduction of international guidelines for the standardisation of procedures. These are evident in the results of our regression analysis, with the difference between groups being the equations and what influenced these (i.e. the sample, the equipment used) linked to the date of data collection. As the cohort and the period effects are both applicable around the globe, it is therefore likely that the Morris lung age equations are no longer relevant in other countries with a Caucasian population.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The strengths of this research include the development of new lung age equations that can be used in many different areas worldwide. It is likely that these will each be more applicable to their relevant populations than the Morris equations. Further, a large independent dataset of community-based males and females who were randomly selected was used for comparisons. ‘Phantom’ subjects were used for some comparisons, which removes any bias caused by external influences on lung function such as other inhalational exposures (e.g. occupational exposures, environmental tobacco smoke, or exposure to indoor or outdoor pollution), previous childhood respiratory infections, socioeconomic status, etc. Decreasing lung function was simulated by substituting decreasing values of FEV1.

A limitation may be that our independent dataset was an urban sample from an industrialised area of Adelaide. The results may not be the same in rural populations, although the findings using the phantom subjects suggest they will be similar. It might be thought that lung age estimates should be similar to chronological age for healthy never smokers. In this analysis, the Newbury lung age equations appeared to overestimate lung age in the healthy never-smoker subgroup of the NWAHS dataset whereas lung age estimates using these equations closely approximated chronological age using the workplace dataset.10 A possible explanation for this is that the NWAHS sample may not be as healthy as the original reference cohort. The Newbury predictive equations were created using a sample of healthy volunteers in a rural town with no heavy industry.22 In contrast, the north-west area of Adelaide includes areas of heavy industry, often in close proximity to residential areas.23 This may also explain the paradoxical results in younger females shown in Figure 2.

Interpretation of findings in relation to previously published work

The Step2Quit trial from 20083 used the Morris lung age equations and communicated spirometry results as lung age when this estimate was greater than chronological age. Although this study reported significantly higher quit rates in the intervention group, our results suggest that the Morris equations may also have underestimated lung age in their sample whereas an updated equation may have given stronger results.

The results of the current study, using both the phantom subjects and the NWAHS dataset, are very similar to the previous comparison using the workplace dataset.10 Both studies have used independent datasets to ensure robust validation.

The concept of lung age has recently been questioned, but without regard to the dates of data collection for the predictive equations used.7 Instead, we suggest that the differences seen between lung age estimates are related to the cohort and period effects that are central to the ‘age’ of the equation in use. This is supported by the ATS/ERS recommendation that lung function predictive equations be regularly updated,20 but is in direct contrast to the ERS Task Force to Establish Improved Lung Function Reference Values (TF-2009–03) that has recently investigated the pooling of existing datasets to develop predictive equations that are widely applicable around the globe.

This Task Force recently reported that “… no evidence was found of secular trends in data collected from white subjects over the past 30 years”.24

The debate about the validity of using lung age as an intervention to reduce smoking rates continues worldwide. Proponents claim that it is merely a method of communication of results aimed at increasing smoking cessation.5,6,25 Those against claim it is unscientific to infer that high lung age estimates (and therefore low FEV1 values) are due to smoking alone.5,7 Lung function varies between individuals. Ethnicity, sex, age, and height contribute to this, while about 30% of the variation is unaccounted for in healthy never smokers. However, we also know that tobacco smoking is the main contributing factor for COPD in developed countries and that, by stopping smoking earlier, the greater the health benefit will be as the rate of decline in lung function is reduced.26,27 Both sides of the debate agree that regular spirometry results for all smokers, ideally from early adulthood, would enable tracking of each individual's results over time:6,7 however, this is not currently the situation.

A new lung age equation based on FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) was recently published,25 developed using the NHANES III dataset that also informed the equations of Hankinson et al.14 used in our comparison. The authors claim that this equation is superior to those based on FEV1 alone.25,28 We feel that this claim is premature as these equations have not been validated on an independent sample. The fact that they accurately estimate the chronological age in never-smokers in the same sample from which they were derived25,28 is a circular argument.

Implications for future research, policy and practice

This research confirms that newer lung age equations give significantly older estimates of lung age compared with the original Morris equations. A well-designed randomised controlled trial is needed to determine any impact on quit rates. Our paper has limited itself to comparisons of six lung age equations based on predictive equations for FEV1. Further research will investigate the lung age equations based on FEV1/FVC by using independent datasets, the reporting of which will follow.

We recommend that spirometry should be performed on smokers aged >35 years. If the latest relevant predictive equations determine that FEV1 is <80% predicted, then lung age can be estimated as part of smoking cessation counselling using an up-to-date lung age equation that is relevant to that population.

Conclusions

Our message is twofold. First, our research confirms the need to update predictive equations for lung function regularly as recommended by the ATS/ERS.20 Predictive equations from 15–20 (and even 40) years ago should not be in use in 2011 and will predict erroneous values if used. Second, our results show that, if lung age is to be used in smoking cessation counselling, then an appropriate lung age equation should be used for that population which — like equations used for interpreting lung function tests — should be the most up-to-date one available for that population. Whether everyone agrees on it being a valid intervention or not, lung age is currently being used as an aid in smoking cessation counselling. Using a more up-to-date equation will result in a stronger message and — according to the model of stages and processes of change relating to addictive behaviours developed by Prochaska et al.29 — may motivate smokers to move out of the pre-contemplation stage towards the action stage and therefore quit smoking.

References

Morris J, Temple W . Spirometric “lung age” estimation for motivating smoking cessation. Prev Med 1985;14:655–62. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0091-7435(85)90085-4

Fletcher C, Peto R . The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction. BMJ 1977;1:1645–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.1.6077.1645

Parkes G, Greenhalgh T, Griffin M, Dent R . Effect on smoking quit rate of telling patients their lung age: the Step2Quit randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2008;336:598–600. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39503.582396.25

Parker D, Goldman R, Eaton C . A qualitative study of individuals at risk for or who have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: what do they understand about their disease? Lung 2008;186:313–16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00408-008-9091-9

Hansen J . Lung age is a useful concept and calculation. With authors' reply from Quanjer P and Enright P. Prim Care Respir J 2010;19:400–01. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2010.00074.

Parkes G, Greenhalgh T . Paradoxes of spirometry results, and smoking cessation. Prim Care Respir J 2010;19:295–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2010.00056.

Quanjer P, Enright P . Should we use ‘lung age’? Prim Care Respir J 2010;19:197–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2010.00045.

McLure J, Ludman E, Grothaus L, Pabiniak C, Richards J . Impact of a brief motivational smoking cessation intervention. The Get PHIT Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Prev Med 2009;37:116–23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.03.018.

Morris J, Koski A, Johnson L . Spirometric standards for healthy nonsmoking adults. Am Rev Respir Dis 1971;103:57–67.

Newbury W, Newbury J, Crockett A . Exploring the need to update lung age equations. Prim Care Respir J 2010;19:242–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2010.00029

Quanjer P . Standardized lung function testing. Bull Eur Physiopathol Respir 1983;19(Suppl 5):1–95.

Quanjer P, Tammeling G, Cotes J, Pedersen O, Peslin R, Yernault J-C . Lung volumes and forced ventilatory flows. Report Working Party Standardization of Lung Function Tests, European Community for Steel and Coal. Official Statement of the European Respiratory Society. Eur Respir J 1993;6(Suppl 16):5–40.

Stanojevic S, Wade A, Stocks J . Reference values for lung function: past, present and future. Eur Respir J 2010;36:12–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031036.00143209

Hankinson J, Odencrantz J, Fedan K . Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;159:179–87.

Falaschetti E, Laiho J, Primatesta P, Purdon S . Prediction equations for normal and low lung function from the Health Survey for England. Eur Respir J 2004;23:456–63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.04.00055204

Gore C, Crockett A, Pederson D, Booth M, Bauman A, Owen N . Spirometric standards for healthy adult lifetime nonsmokers in Australia. Eur Respir J 1995;8:773–82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.95.08050773

Grant J, Chittleborough C, Taylor A, et al. The North West Adelaide Health Study: detailed methods and baseline segmentation of a cohort for selected chronic diseases. Epidemiol Perspect Innov 2006;3:4. http://dx.doi.org/10/1186/1742-5573-3-4.

Grant J, Taylor A, Ruffin R, et al. Cohort Profile: The North West Adelaide Health Study (NWAHS). Int J Epidemiol 2009;38:1479–86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/je/dyn262

American Thoracic Society. ATS Statement — Snowbird workshop on standardization of spirometry. Am Rev Respir Dis 1979;119:831–8.

Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, et al. Interpretive strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J 2005;26:948–68 http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.05.00035205.

Kerstjens H, Rijcken B, Schouten J, Postma D . Decline of FEV1 by age and smoking status: facts, figures, and fallacies. Thorax 1997;52:820–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thx.52.9.820

Newbury W, Crockett A, Newbury J . A pilot study to evaluate Australian predictive equations for the Impulse Oscillometry System. Respirology 2008;13:1070–5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1843.2008.01375.x

Whitrow M . The association between air pollution and lung cancer in the North West of Adelaide: a case control study and air quality monitoring [PhD Thesis]. Adelaide: The University of Adelaide; 2004. http://digital.library.adelaide.edu.au/dspace/bitstream/2440/37750/1/02whole.pdf

Quanjer P, Stocks J, Cole T, Hall G, Stanojevic S . Influence of secular trends and sample size on reference equations for lung function tests. Eur Respir J 2011;37:658–64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00110010

Hansen J, Sun X-G, Wasserman K . Calculating gambling odds and lung ages for smokers. Eur Respir J 2010;35:776–80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00107709

Anthonisen N, Connett J, Murray R . Smoking and lung function of Lung Health Study participants after 11 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:675–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.2112096

Kohansal R, Martinez-Camblor P, Agusti A, Buist A, Mannino D, Soriano J . The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction revisited. An analysis of the Framingham Offspring Cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180:3–10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200901-0047OC

Hansen J . Measuring the lung age of smokers. Prim Care Respir J 2010;19:286–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2010.00048

Prochaska J, DiClemente C, Norcross J . In search of how people change. Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist 1992;47:1102–14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.47.9.1102

Acknowledgements

Handling editor Mike Thomas

Statistical review Gopal Netuveli

Funding None.

This manuscript has been reviewed for scientific content and consistency of data interpretation by Chief Investigators of the North West Adelaide Health (NWAH) Study. The NWAH Study team are most grateful for the generosity of the cohort participants in the giving of their time and effort to the study. The NWAH study team is also appreciative of the work of the clinic, recruiting and research support staff for their substantial contribution to the success of the study. We would also like to thank Professor Jonathan Newbury and Associate Professor Tjaarda Schermer for their very useful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WN and AC had access to the data, and were responsible for conception and design of the study, as well as interpretation, analysis and writing. ML contributed to the analysis, interpretation and writing. WN and AC contributed to the revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Newbury, W., Lorimer, M. & Crockett, A. Newer equations better predict lung age in smokers: a retrospective analysis using a cohort of randomly selected participants. Prim Care Respir J 21, 78–84 (2012). https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2011.00094

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2011.00094