Abstract

Spinocerebellar degeneration (SCD) is a clinically and genetically diverse group, and the dominant form of SCD (AD-SCD) is generally referred to as spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA) that primarily affects the cerebellum. Some patients do not have a definitive genetic diagnosis but may carry unknown variants of known causative genes. Here, we screened for known SCA-associated genes in patients with suspected SCA. We examined 174 patients with SCA lacking abnormal repeat expansion of known causative genes. Whole-exome sequencing (WES) was performed to screen for variants in SCA-associated genes. The identified variants were confirmed by Sanger sequencing, and their pathogenicity was determined using five web-based algorithms. WES revealed novel single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) in three genes, ELOVL4, ELOVL5, and GRM1. Patients presented with symptoms other than cerebellar symptoms. One patient with an ELOVL4 variant exhibited skin changes, a typical symptom of ELOVL4 SCA, whereas the other ELOVL4 SCA patient had no skin changes and exhibited mild parkinsonism and calcification in the globus pallidus and dentate nucleus. The patient with an ELOVL5 variant exhibited bladder and rectal disturbances. Finally, patients with GRM1 variants showed few common features beyond the cerebellar symptoms. One patient showed white matter lesions, cognitive decline, and no-no head tremors, whereas the other showed spasticity. The identification of novel SNVs in these known SCA-associated genes will expand our understanding of the genetic landscape of SCA and facilitate the diagnosis of previously undiagnosed patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spinocerebellar degeneration (SCD) is a clinically and genetically diverse group, and the dominant form of SCD (AD-SCD) is generally referred to as spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA). SCA primarily affects the cerebellum and its associated pathways. SCA is clinically characterized by progressive ataxia, dysarthria, and oculomotor disturbances. Numerous novel genes have been identified by next-generation sequencing techniques [1]. More than 50 genes are listed as causative genes of SCA in Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM, https://www.omim.org/). The large number of pathogenic variants of SCA highlights the complexity and diversity of its molecular etiology. Despite significant progress in the identification of disease-causing mutations, some patients do not have a definitive genetic diagnosis.

Whole exome sequencing (WES) enables the comprehensive screening of coding regions across the genome, facilitating the detection of both novel and previously reported single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) that underlie inherited disorders. Although WES has some limitations [2], it is a powerful tool for uncovering the genetic basis of diseases, including ataxia [3, 4].

In this study, we aimed to perform WES on a cohort of patients presenting with clinical features consistent with SCA. Our analysis revealed several novel SNVs in genes previously associated with the disorder. Specifically, we identified novel variants of ELOVL4, ELOVL5, and GRM1. The identification of novel SNVs in these known SCA-causing genes can expand our understanding of the genetic landscape of SCA.

Materials and methods

Subjects

We examined 174 patients with SCA who had no abnormal repeat expansions of known causative genes (for SCA1, SCA2, SCA3, SCA6, SCA7, SCA8, SCA31, SCA36, and dentatorubral–pallidoluysian atrophy). Each participant was diagnosed with SCA by neurologists. The mean age of the participants was 46.3 years (SD = 16.1, range = 10–82). Dominant inheritance was suspected in 173 cases out of 174 cases, and only one patient had no family history but was highly suspected of having SCA based on symptoms. The Ethics Committee of Hiroshima University approved the study protocol. All experiments were conducted after obtaining written informed consent from the patients or their family members.

Genetic analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from the peripheral blood leukocytes of the patient using QuickGene-610L (Wako, Osaka, Japan). WES was performed using the BGI platform (Shenzhen, Guangdong, China). Mapping to the human reference genome (GRCh38) was performed using the BWA tool, with the removal of duplicate reads using Picard. Variant calls and annotations were made using GATK and Annovar software. We analyzed the variants of known SCA genes including SPTBN2, TTBK2, KCNC3, PRKCG, ITPR1, KCND3, TMEM240, PDYN, PNPT1, EEF2, FGF14, AFG3L2, ITPR1, ELOVL4, TGM6, ELOVL5, CCDC88C, TRPC3, CACNA1G, MME, GRM1, FAT2, PLD3, STUB1, SAMD9L, and NPTX1. We included the variants as candidate using the criteria: frequency in the database < 0.001; missense, nonsense, and indel variants; and depth > 4. The candidate variants were verified using Sanger sequencing using an Applied Biosystems 3130 DNA Sequencer (Life Technologies). Variants were evaluated by predictive algorithms (AlphaMissense [https://alphamissense.hegelab.org/], Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion [CADD, https://cadd.gs.washington.edu/], Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant [SIFT, https://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/], PolyPhen-2 [http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/], and MutationTaster [http://www.mutationtaster.org/]), which predicted whether amino acid substitutions would affect protein function. Allele frequencies were obtained from gnomAD (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/) and the National Center Biobank Network (NCBN) database [5] using TogoVar (https://grch38.togovar.org/).

Results

Overview

WES of the cohort of patients with clinical symptoms consistent with SCA revealed novel SNVs in ELOVL4, ELOVL5, and GRM1 in 5 patients. The genomic and clinical features of each patient are summarized in Table 1. We also identified 49 benign variants in 42 individuals and no known pathogenic variants in SCA-associated genes. The diagnostic yield was 2.9% (5/174).

ELOVL4

Patients 1 and 2 harbored a missense variant of ELOVL4 (Patient 1: c.507G > C,p.W169C; Patient 2: c.542C > T,p.A181V). ELOVL4 (elongation of very long-chain fatty acid-like 4; MIM 605512) was associated with SCA34 (MIM 133190). Skin changes, which have been previously reported as a characteristic of SCA with ELOVL4 variants [6, 7], were observed in Patient 1 but not in Patient 2. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head showed cerebellar and brainstem atrophy (Fig. 1A, C, D). T2-weighted images (T2WI) of Patient 1 showed the hot cross bun sign, which is characteristic of multiple system atrophy (MSA) (Fig. 1A, B). Patient 1 had no family history of the disease. Her parents were asymptomatic, but their genetic tests have not been conducted. The ELOVL4 variant was predicted to be pathogenic by all five predictive algorithms. Calcification in the globus pallidus and dentate nucleus was observed on the head CT scan of patient 2 (Fig. 1E). Her mother, who was suspected of developing the disease without genetic testing, did not show any calcification in her brain. Patient 2 exhibited mild Parkinsonism, such as postural and intentional tremors and rigidity.

Head images of the patients with ELOVL4 variants. A Axial T2-weighted images of Patient 1 show cerebellar and brainstem atrophy as well as the hot cross bun sign in the pons. B The hot cross bun sign is clearly observed in the enlarged images of the pons in (A). C Sagittal T1-weighted image of Patient 1 showing the cerebellar vermis and brainstem atrophy. D Axial T1-weighted images of Patient 2, showing mild cerebellar and brainstem atrophy. E Head computed tomography of Patient 2 showing calcifications in the globus pallidus and dentate nucleus

ELOVL5

Patient 3 harbored a missense variant in ELOVL5 (c.179C > T, p.S60F). ELOVL5 (elongation of very long-chain fatty acid-like 5; MIM 611805) was associated with SCA38 (MIM 615957). The patients exhibited slowly progressive SCA with limb ataxia, truncal ataxia, dysarthria, saccadic eye movement, and bladder and rectal disturbances. His head MRI data were lost and cannot be presented, but cerebellar and brainstem atrophy was confirmed from the medical record entries.

GRM1

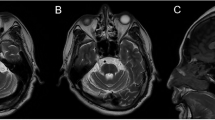

Patients 4 and 5 harbored missense variants in GRM1 (patient 4: c.3563A > C,p.K1188T; patient 5: c.1849T > C,p.Y617H). GRM1 (glutamate receptor metabotropic 1; MIM 604473) is associated with SCA44 (MIM 617691). The patients exhibited slowly progressive SCA with limb ataxia, saccadic eye movement, and dysarthria. Patient 4 presented with truncal ataxia, no-no head tremor, or cognitive decline (the mini-mental state examination: 15). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the patient’s head showed severe white matter lesions (Fig. 2A) and atrophy of the cerebellum and brainstem (Fig. 2A, B). Patient 5 exhibited spasticity and cerebellar atrophy (Fig. 2C, D).

Head images of the patients with GRM1 variants. A Axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images of Patient 4 show cerebellar and brainstem atrophy and white matter lesions in the periventricular and subcortical regions. B Sagittal T1-weighted image of Patient 5, showing cerebellar and brainstem atrophy. Axial (C) and sagittal (D) T1-weighted images of Patient 5 showed cerebellar and brainstem atrophy

Discussion

Using WES, we identified five candidate pathogenic variants in these three genes. Previously reported cases of ELOVL4 SCA presented with skin changes in childhood [6, 7]; however, Patient 2 did not exhibit any skin abnormalities. Notably, a previously reported Japanese family with an ELOVL4 SCA variant also did not exhibit skin changes [8], suggesting that Japanese patients are less likely to develop skin lesions than European patients. The hot cross bun sign was observed in Patient 1 as well as in a Japanese ELOVL4 SCA family [8]. As the hot cross bun sign can also be observed in MSA and several SCAs (including SCA1, 2, 3, 6, 7, and 8) [9], careful differential diagnosis is essential. Patient 2 exhibited mild Parkinsonism and calcification in the globus pallidus and dentate nucleus, which have not been previously reported. Since her suspected mother did not show any calcification in her brain, this may not be a characteristic feature of this variant. Japanese patients with ELOVL4 variants have been reported to show autonomic disturbances, which were not observed in our ELOVL4 cases. According to the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) criteria [10], both two patients were classified as Uncertain significance. Skin changes and the hot cross bun sign observed in Patient 1 are considered possible findings, however, whether autonomic disturbances and calcification in the brain observed in Patient 2 are characteristics of ELOVL4 SCA in Japanese patients remains to be clarified and requires further investigation requires further investigation.

The present case of an ELOVL5 variant exhibited bladder and rectal disturbances, but previous reports have not mentioned these symptoms [11]. According to the ACMG criteria, this patient was classified as Uncertain significance. Whether autonomic disturbances are characteristics of ELOVL5 SCA in Japanese patients remains to be seen.

Patients with GRM1 variants exhibited few common features, other than cerebellar symptoms. One patient showed white matter lesions, cognitive decline, and no-no head tremors, whereas the other showed spasticity. Some previous GRM1-related SCA exhibited spasticity [12], but none reported cognitive decline. The cognitive decline observed in our patient may have been related to white matter lesions associated with atherosclerosis because this patient had dyslipidaemia and hypertension. Both variants were classified as Uncertain significance based on the ACMG criteria. We need some other cases to determine clinical significance.

The diagnostic yield in this study was lower than that reported in the previous studies of genetic screening for autosomal dominant ataxia. Those studies reported the diagnostic yield was 14.3% [13] and 32% [14], respectively, whereas it was 2.9% in our cohort. The discrepancy is likely attributable to differences in the ethnic backgrounds of study participants and the target genes analyzed.

This study has several limitations. First, most cases could not be segregated because of the lack of family testing. Second, a functional analysis of the variant proteins was not performed. Finally, it should be noted that SCA27B, which is an important subtype in Japanese patients with SCA, was not excluded in this study. It is crucial to accumulate additional data from other families with SCA in the future.

We screened for SCA cases and identified five candidate pathogenic variants in three genes. We hope that the present findings will be valuable in future clinical practice regarding SCA.

References

Sullivan R, Yau WY, O’Connor E, Houlden H. Spinocerebellar ataxia: an update. J Neurol. 2019;266:533–44.

Ngo KJ, Rexach JE, Lee H, Petty LE, Perlman S, Valera JM, et al. A diagnostic ceiling for exome sequencing in cerebellar ataxia and related neurological disorders. Hum Mutat. 2020;41:487–501.

Kim M, Kim AR, Kim JS, Park J, Youn J, Ahn JH, et al. Clarification of undiagnosed ataxia using whole-exome sequencing with clinical implications. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2020;80:58–64.

Nibbeling EAR, Duarri A, Verschuuren-Bemelmans CC, Fokkens MR, Karjalainen JM, Smeets C, et al. Exome sequencing and network analysis identifies shared mechanisms underlying spinocerebellar ataxia. Brain. 2017;140:2860–78.

Kawai Y, Watanabe Y, Omae Y, Miyahara R, Khor SS, Noiri E, et al. Exploring the genetic diversity of the Japanese population: insights from a large-scale whole genome sequencing analysis. PLoS Genet. 2023;19:e1010625.

Giroux JM, Barbeau A. Erythrokeratodermia with ataxia. Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:183–8.

Cadieux-Dion M, Turcotte-Gauthier M, Noreau A, Martin C, Meloche C, Gravel M, et al. Expanding the clinical phenotype associated with ELOVL4 mutation: study of a large French-Canadian family with autosomal dominant spinocerebellar ataxia and erythrokeratodermia. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:470–5.

Ozaki K, Doi H, Mitsui J, Sato N, Iikuni Y, Majima T, et al. A novel mutation in ELOVL4 leading to spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA) with the hot cross bun sign but lacking erythrokeratodermia: a broadened spectrum of SCA34. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:797–805.

Naidoo AK, Wells CD, Rugbeer Y, Naidoo N. The “Hot Cross Bun Sign” in spinocerebellar ataxia types 2 and 7-case reports and review of literature. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2022;9:1105–13.

Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–24.

Di Gregorio E, Borroni B, Giorgio E, Lacerenza D, Ferrero M, Lo Buono N, et al. ELOVL5 mutations cause spinocerebellar ataxia 38. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;95:209–17.

Watson LM, Bamber E, Schnekenberg RP, Williams J, Bettencourt C, Lickiss J, et al. Dominant Mutations in GRM1 Cause Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 44. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;101:451–8.

Coutelier M, Coarelli G, Monin ML, Konop J, Davoine CS, Tesson C, et al. A panel study on patients with dominant cerebellar ataxia highlights the frequency of channelopathies. Brain. 2017;140:1579–94.

Hadjivassiliou M, Martindale J, Shanmugarajah P, Grünewald RA, Sarrigiannis PG, Beauchamp N, et al. Causes of progressive cerebellar ataxia: prospective evaluation of 1500 patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88:301–09.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Ms. Nakajima for her technical assistance. This work was funded by the Research Committee of Ataxia, Health Labor Sciences Research Grant, Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (JMPH23C1010). We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Hiroshima University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Hideshi Kawakami; Data curation: Kodai Kume; Methodology: Hideshi Kawakami; Formal analysis and investigation: Tomoaki Watanabe, Kodai Kume; Resources: Ken Inoue, Masataka Nakamura, Shinji Yamamoto, Takashi Kurashige, Tomohiko Ohshita, Taku Tazuma, Misako Kaido; Writing – original draft preparation: Tomoaki Watanabe; Writing – review and editing: Kodai Kume, Yuta Maetani, and Hirofumi Maruyama; Supervision: Hideshi Kawakami.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Watanabe, T., Kume, K., Inoue, K. et al. Whole exome sequencing in Japanese spinocerebellar ataxia identifies novel variants. J Hum Genet 71, 35–39 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s10038-025-01405-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s10038-025-01405-2