Abstract

Tumor fibrosis is recognized as a malignant hallmark in various solid tumors; however, the clinical importance and associated molecular characteristics of tumor fibrosis in liver metastases (LM) from colorectal cancer (CRLM) remain poorly understood. Here we show that patients with CRLM whose liver metastases (LM) exhibited tumor fibrosis (Fibrosis+ LM) had significantly worse progression-free survival (P = 0.025) and overall survival (P = 0.008). Single-cell RNA sequencing revealed that the tumor microenvironment of the Fibrosis+ LM was characterized by T cells with an exhausted phenotype, macrophages displaying a profibrotic and suppressive phenotype and fibrosis-promoting fibroblasts. Further investigation highlighted the pivotal role of VCAN_eCAF in remodeling the tumor fibrosis in the tumor microenvironment of Fibrosis+ LM, emphasizing potential targetable interactions such as FGF23 or FGF3-FGFR1. Validation through multiplex immunohistochemistry/immunofluorescence and spatial transcriptomics supported these findings. Here we present a comprehensive single-cell atlas of tumor fibrosis in LM, revealing the intricate multicellular environment and molecular features associated with it. These insights deepen our understanding of tumor fibrosis mechanisms and inform improved clinical diagnosis and treatment strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The liver is the most common site of metastasis (occurring in over 50% of cases) and a leading cause of death among patients with colorectal cancer1. Although surgery remains the cornerstone of treatment for colorectal liver metastases (CRLM), the recurrence rates exceed 50% within the first 2 years following resection2, which is closely associated with poorer overall survival (OS). Furthermore, the efficacy of systemic treatments for unresectable CRLM is still suboptimal; for instance, the objective response rate for patients with CRLM treated with FOLFOX in combination with bevacizumab was approximately 50% (ref. 3). Consequently, a deeper understanding of the heterogeneity within the tumor microenvironment (TME) of liver metastasis (LM) may provide novel insights for therapeutic strategies targeting patients with CRLM4.

Tumor fibrosis was characterized by the pathological accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) components within tumor tissue5. Previous studies have demonstrated a correlation between tumor fibrosis and an immunosuppressive TME in various solid tumors, including breast cancer6,7, non-small-cell lung cancer8 and hepatocellular carcinoma9. This association may be attributed to the role of a rigid ECM as a physical barrier, as well as the phenotypic reprogramming of dendritic cells, macrophages and other immune cells, which leads to lymphocyte suppression6,7,8,9. Collectively, these factors may contribute to resistance to immunotherapy, particularly immune checkpoint inhibitors, ultimately resulting in adverse patient outcomes10. In recent years, antifibrotic therapies have increasingly shown promise in overcoming tumor resistance to immunotherapy and chemotherapy11. The influence of tumor fibrosis on the TME has become a focal point in clinical research.

However, in the context of CRLM, the clinical implications of tumor fibrosis in LM remain poorly understood. And a comprehensive characterization of the molecular features between tumor fibrosis present (Fibrosis+) LM and tumor fibrosis absent (Fibrosis−) LM at the single-cell resolution level remains lacking. This study aims to explore these issues from the aforementioned perspectives, providing clinicians with new perspectives for consideration.

Methods

Analysis of the association between tumor fibrosis in LM and survival

A flow diagram illustrating the study’s analyses is depicted in Fig. 1. Ultimately, 471 patients with colorectal cancer LM receiving resection were retrospectively reviewed. Supplementary Table 1 details the clinicopathologic variables of interest for outcome analyses. Surgically resected specimens of LM were fixed with formalin, sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Two certified pathologists independently evaluated tumor fibrosis and subsequently reached a consensus through collective assessment. In the case of a discordant outcome, the specimens were reviewed by a third independent expert pathologist.

From left to right: Pathological assessment of liver metastasis fibrosis (top left), evaluation of clinical prognostic value (bottom left), overview of single-cell transcriptome analysis (center), multiplex immunofluorescence validation (top right), and spatial transcriptome analysis validation (bottom right).

Outcomes included progression-free survival (PFS) and OS. Multiple imputations via chained equations were performed to address the missing data. The observed variances in baseline characteristics were adjusted using the inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) method. According to Rubin’s rules, estimated propensity scores from imputed datasets were amalgamated by computing the mean across all datasets. Standardized differences (SD), with a threshold of <0.1, were utilized to evaluate baseline characteristic balance. Adjusted Kaplan–Meier curves and log-rank tests based on IPTW were used to compare PFS and OS across groups. Furthermore, an inverse probability weighted Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to assess the relative hazard change (IPTW-adjusted hazards ratio (HR)). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 (two-sided), and all analyses were conducted using R version 4.1.1.

Single-cell RNA sequencing for Fibrosis+ LM versus Fibrosis− LM

Sample collection and data processing for single-cell RNA sequencing

Single-cell RNA sequencing was performed on ten LM samples collected from ten patients with CRLM who underwent surgery without previous treatment. Clinical information for the enrolled patients is summarized in Supplementary Table 2. These samples were stratified into Fibrosis+ LM and Fibrosis− LM, with five samples in each group. The single-cell RNA sequencing data processing and analysis were performed as follows: the raw reads were computationally mapped to the GRCh38 human reference genome, with subsequent gene expression quantification at single-cell resolution performed using CellRanger software. These gene-cell count matrices were then imported into Seurat (v4.0.2) for downstream analysis. Following the quality control procedures detailed in the Supplementary Information, we implemented an established single-cell RNA sequencing analysis pipeline for clustering and annotation12,13,14. In brief, filtered cells underwent normalization and variance stabilization through SCTransform15, which simultaneously identified highly variable genes for downstream dimensional reduction. Principal component analysis was performed, with the optimal dimensionality determined via elbow plot assessment. Cell clustering was achieved through nearest-neighbor graph construction (FindNeighbors()) and community detection algorithms (FindClusters()), with results visualized using uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) dimensionality reduction. For the cellular annotation, cluster-specific marker genes were identified using FindAllMarkers(), considering only significantly upregulated transcripts. The major cell types were classified on the basis of established markers12,13,14: epithelial cells (EPCAM and KRT19), T and natural killer (NK) cells (CD3D, CD4, CD8A and PTPRC), myeloid cells (CD68, CD163, CD14 and LYZ), endothelial cells (CLDN5 and CDH5), fibroblasts (ACTA2, DCN and FAP), mast cells (TPSAB1, TPSB2 and MS4A2), B cells (CD19, CD79A and MS4A1) and plasma cells (IGHG1, IGHA1 and MZB1). To resolve cellular heterogeneity, iterative subclustering was performed on major populations using the abovementioned analytical workflows (normalization, dimensional reduction and clustering), enabling the identification of distinct subtypes based on characteristic marker gene expression profiles. More detailed sample processing and quality control procedures can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Comparing cell type proportions

To evaluate differences in cellular composition within the TME between Fibrosis+ LM (n = 5) and Fibrosis− LM (n = 5) groups, we initially used the ratio of observed to expected cell numbers (Ro/e) (ref. 16) to assess the enrichment or depletion of individual cell clusters; an Ro/e value >1 indicates enrichment, whereas an Ro/e value <1 indicates depletion across the two groups. MiloR17, known for its discriminatory power in differential abundance, was also utilized to validate these findings. Subsequently, we used compared cell proportions of distinct cell subsets using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and assessed the statistical significance.

Functional enrichment analysis

To characterize the functional heterogeneity of distinct cellular subpopulations, we performed gene set enrichment analysis using irGSEA to evaluate the well-established transcriptional signatures for T cell subsets (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4) and myeloid lineages (Supplementary Table 5), as previously defined in published studies16,18,19. This integrative analytical framework incorporates multiple single-cell enrichment algorithms—including AUCell, UCell, singscore, ssGSEA, JASMINE and Viper—to systematically profile the pathway activation dynamics across heterogeneous cell clusters. By implementing a consensus-based ranking strategy, we aggregated results from these complementary computational methods, thereby enabling a robust and multidimensional evaluation of pathway enrichment. In addition, aggregated normalized expression levels of predefined gene sets were computed using AddModuleScore function, enabling complementary insights into cellular phenotypes.

Pseudotime analysis

The R package Slingshot20 was then used to delineate potential lineage differentiation trajectories. All the trajectory starting points in this study were based on an integrated approach combining two methods: first, the automatic selection by the Slingshot algorithm and, second, biologically meaningful judgments supported by literature evidence. In cases of discrepancy, biological importance was prioritized. Moreover, generalized additive models were used to investigate the relationship between signature scores and pseudotimes derived from the Slingshot algorithm. Furthermore, the Geneswitches algorithm21 was applied to the pseudotime trajectories of specific cell clusters to predict pivotal changes in gene expression and pathway enrichment across pseudotime.

Tumor fibrosis responsiveness analysis by Augur

Augur22 represents a tailored machine learning approach designed to assess the priority of cell types within single-cell RNA sequencing datasets. By measuring the intensity of transcriptional responses across various cell types exposed to biological perturbations, Augur identifies the most responsive cell types under specific conditions.

Exploration of cell–cell interactions

To delineate the intercellular communication and differential signal pathways among distinct cell clusters within the TME, we utilized the Cellchat package23. In addition, the iTALK package24 was used to identify significant alterations in ligand–receptor (LR) interactions across cell clusters within the TME of the Fibrosis+ LM and Fibrosis− LM. The known LR pairs encompassing checkpoint, cytokine and growth factor interactions were investigated.

Validation using mIHC/IF

To validate the differential distribution of cell clusters identified from single-cell RNA sequencing between Fibrosis+ LM and Fibrosis− LM, we used multiplex immunohistochemistry/immunofluorescence (mIHC/IF). The LM samples from patients with CRLM who underwent surgery without prior treatment were categorized into Fibrosis+ LM (n = 25) and Fibrosis− LM (n = 25) for the mIHC/IF analysis. The clinical details for these patients are provided in Supplementary Table 6. The detailed procedures for mIHC/IF can be found in the Supplementary Information. We conducted comparisons of specific cell subcluster densities between the Fibrosis+ LM and Fibrosis− LM.

Validation using ST data

Spatial transcriptomics (ST) data analysis utilized two datasets (GSE225857 and GSE217414) obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus. These datasets were processed using the Load10X_Spatial function from the Seurat package, focusing specifically on six LM samples from patients with CRLM (Supplementary Table 7). Tumor fibrosis levels in the ST data were evaluated using a curated gene signature as previously described25.

For deconvolution and cell type annotation, the integrated analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing and ST data was performed using the ‘CARD’ (v 1.1) package26 with default parameters. A ‘CARD’ object was initially created using the CreateCARDObject function, followed by applying CARD_deconvolution with default parameters to compute results. The relationship between cellular organization and tumor fibrosis was explored by evaluating the homotypic scores of selected cell clusters for spatial localization, following established methodologies27.

To further assess the correlation between tumor fibrosis levels and cell proportions across spatial locations, we utilized the SPATA2 R package28. The Seurat object was transformed into a Spata object using the transformSeuratToSpata function. Subsequently, notable variations in tumor fibrosis scores were visualized through a spatial trajectory created using the createTrajectories function. The changes in the cell proportions along this trajectory were visualized using the plotTrajectoryFeaturesDiscrete function. Moreover, the spatial colocalization of specific LR interactions was assessed using SpaGene29.

Results

Survival analyses for fibrosis in LM

Supplementary Fig. 1a, b illustrates the representative hematoxylin and eosin images of LM with (Supplementary Fig. 1a) and without (Supplementary Fig. 1b) tumor fibrosis. The clinicopathologic characteristics of included patients are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. The patients were stratified into two groups: fibrosis in LM (n = 97) and no fibrosis in LM (n = 374). The initial imbalances observed between the groups within the unadjusted cohort were effectively mitigated post adjustment (Supplementary Table 1).

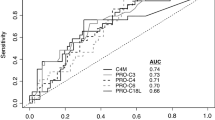

The patients with fibrosis in LM demonstrated significantly worse PFS compared with those with no fibrosis in LM both before (median: 7.0 months versus 12.7 months, P < 0.001 in non-IPTW-adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, HR 1.610) and after adjustment (median: 9.9 months versus 12.4 months, P = 0.025 in IPTW-adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, HR 1.391) (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). The patients with fibrosis in LM demonstrated significantly worse OS compared with those with no fibrosis in LM both before (median: 42.0 months versus 66.6 months, P = 0.003 in non-IPTW-adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, HR 1.678) and after adjustment (median: 46.0 months versus 58.8 months, P = 0.008 in IPTW-adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, HR 1.728) (Supplementary Fig. 2c, d).

Single-cell RNA sequencing analysis of Fibrosis+ LM versus Fibrosis− LM

Global single-cell landscape for Fibrosis+ LM versus Fibrosis− LM

We performed single-cell RNA sequencing to compare the cellular composition between patients with high and Fibrosis− in CRLM. Across all samples, we identified eight main cell types, including T and NK cells (CD3D, CD3G and PTPRC), B cells (CD19, CD79A and MS4A1), plasma cells (IGHG1, IGHA1 and MZB1), myeloid cells (CD68, CD163, CD14 and LYZ), epithelial cells (EPCAM and KRT19), fibroblasts (FAP, DCN and ACTA2), endothelial cells (CLDN5 and CDH5) and mast cells (TPSAB1, TPSB2 and MS4A2)12,13,14 (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). Notably, although Fibrosis− LM samples showed a tendency toward higher prevalence of T and NK cells and endothelial cells, and Fibrosis+ LM samples exhibited a relative enrichment of epithelial and myeloid cells (Supplementary Fig. 3c), these differences did not reach statistical significance (Supplementary Fig. 3d).

T cells reprogramming toward a suppressive microenvironment in TME of Fibrosis+ LM

Tumor-infiltrating T cells play a pivotal role in the TME, yet their heterogeneous nature poses challenges for effective immunotherapy. Our analysis focused on CD4+ T cell clusters, delineated into FOS+CD4+ memory T cells (FOS_CD4_Tm), ANXA1+CD4+ memory T cells (ANXA1_CD4_Tm), SELL+CD4+ naive T cells (SELL_CD4_Tn), CXCL13+CD4+ exhausted cells (CXCL13_CD4_Tex), CTLA4+CD4+ regulatory T cells (CTLA4_CD4_Treg) and STMN1+CD4+ proliferative T cells (STMN1_CD4_Tpro) (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 8). Notable variations in CD4+ T cell states and compositions were observed between Fibrosis+ and Fibrosis− LMs (Fig. 2a, b). The analysis using Ro/e and MiloR algorithms revealed a higher proportion of CTLA4_CD4_Treg, CXCL13_CD4_Tex and STMN1_CD4_Tpro cells in the Fibrosis+ LM, whereas ANXA1_CD4_Tm and FOS_CD4_Tm cells were more prevalent in the Fibrosis− LM (Fig. 2b–d). A statistical comparison of the cellular proportions confirmed significantly higher frequencies of CTLA4_CD4_Treg, CXCL13_CD4_Tex and STMN1_CD4_Tpro cells in the Fibrosis+ LM group compared with the Fibrosis− LM group (P < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 4a).

a A UMAP plot illustrating six CD4+ T cell clusters across all samples, color-coded by cell type. b The bar plot illustrates the relative proportion of CD4+ T cell clusters in each sample from the Fibrosis+ LM and Fibrosis− LM. c The lollipop chart displays the prevalence of different CD4+ T cell subgroups between the two groups, estimated by Ro/e. The subgroups favoring the Fibrosis+ LM are positioned above, whereas those favoring the Fibrosis− LM are positioned below. d The beeswarm and box plots depict the distribution of log2-fold differences in neighborhoods across various cell type clusters of CD4+ T cells, estimated by MiloR. The rightward positions indicate higher abundance in the Fibrosis+ LM, whereas the leftward positions indicate higher abundance in the Fibrosis− LM. e A heat map depicting the expression of marker genes across defined CD4+ T cell clusters. The color intensity reflects the average scaled gene expression. f A heat map via irGSEA visualizing the distribution of curated significant gene sets identified by robust rank aggregation across CD4+ T cell clusters. The number of asterisks in the grid’s upper half indicates the P value. g The Slingshot trajectory analysis of CD4+ T cell differentiation reveals two principal divergent trajectories. The cells are color-coded according to their pseudotime. h The density changes of CD4+ T cell subclusters along path 1 and path 2 are shown. i The two-dimensional plots showing expression scores for four representative gene signatures in cells of paths 1 and path 2, respectively, along the inferred pseudotime. j The mIHC/IF images showing the positive expression of CTLA4_CD4_Treg. k The quantification of the density of CTLA4_CD4_Treg between Fibrosis+ LM and Fibrosis- LM group, Wilcox rank-sum test.

Notably, CTLA4_CD4_Treg, CXCL13_CD4_Tex and STMN1_CD4_Tpro cells exhibited the upregulation of exhaustion markers such as TNFRSF4, TIGIT, BATF and IL2RA, indicating impaired functionality30 (Fig. 2e). The STMN1_CD4_Tpro cells showed elevated levels of proliferative markers STMN1 and MKI67, whereas CXCL13_CD4_Tex cells demonstrated an increased expression of dysfunctional marker CXCL13, previously linked to immunotherapy responsiveness31. To evaluate the statistical significance of CD4+ T cell functional scores, we conducted comparative irGSEA analysis (Fig. 2f). STMN1_CD4_Tpro cells showed the significant upregulation of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), glycolysis and Treg signature pathways, along with the downregulation of the naive pathway, consistent with their mature and proliferative phenotype. The SELL_CD4_Tn cells exhibited a significant upregulation of the naive pathway and downregulation of both Treg signature and cytotoxicity pathways, matching their naive functional state. The CXCL13_CD4_Tex cells displayed a marked upregulation of the exhaustion pathway and downregulation of cytotoxicity, aligning with their exhausted phenotype. The CTLA4_CD4_Treg cells showed a significant upregulation of Treg signature and exhaustion pathways, along with the downregulation of the naive pathway, corresponding to their mature immunosuppressive phenotype. The ANXA1_CD4_Tm cells demonstrated a significant upregulation of naive, activation and effector function and glycolysis pathways, consistent with their memory-like phenotype12,13,14,16.

Based on the aforementioned functional phenotypes, previous literature reports14,32,33,34 and the automatic selection by the Slingshot algorithm, SELL_CD4_Tn was selected as the most biologically plausible starting point for trajectory construction. The pseudotime analysis of CD4+ T cell subclusters revealed two predominant differentiation paths originating from SELL_CD4_Tn and progressing through ANXA1_CD4_Tm. Path 1 progresses via CTLA4_CD4_Treg to STMN1_CD4_Tpro, whereas path 2 terminates at FOS_CD4_Tm (Fig. 2g, h). These distinct paths suggest divergent cellular fates, supported by dynamic gene expression patterns along the inferred pseudotime axis. Path 2 shows increased activation and cytotoxicity signatures, whereas path 1 exhibits enhanced stress response and Treg signatures (Fig. 2i). Given the predominance of path 1 cells in the Fibrosis+ LM, CD4+ T cells in the TME may trend toward exhaustion or suppression, potentially impacting immunotherapy responsiveness. The elevated infiltration of CTLA4_CD4_Treg cells, key immunosuppressive cells, in the Fibrosis+ LM was confirmed by mIHC/IF analysis (Fig. 2j, k and Supplementary Fig. 4b, c).

We further characterized CD8+ T cell subsets including KLRB1+CD8+ mucosal-associated invariant T cells (KLRB1_CD8_MAIT), CD55+CD8+ resident-memory T cells (CD55_CD8_Trm), GZMK+CD8+ effective-memory T cells (GZMK_CD8_Tem), ISG15+CD8+ interferon response T cells (ISG15_CD8_Tisg), CXCL13+CD8+ exhausted T cells (CXCL13_CD8_Tex) and STMN1+CD8+ proliferative T cells (STMN1_CD8_Tpro) (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 9). Ro/e and MiloR analysis revealed a higher proportion of CXCL13_CD8_Tex and STMN1_CD8_Tpro cells in the Fibrosis+ LM, whereas GZMK_CD8_Tem cells were more prevalent in the Fibrosis− LM (Fig. 3b–d). The statistical comparison of cellular proportions confirmed significantly higher frequencies of CXCL13_CD8_Tex and STMN1_CD8_Tpro in the Fibrosis+ LM group compared with the Fibrosis− LM group (P < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 5a).

a A UMAP plot illustrating six CD8+ T cell clusters across all samples, color-coded by cell type. b The bar plot illustrates the relative proportion of CD8+ T cell clusters in each sample from the Fibrosis+ LM and Fibrosis− LM. c The lollipop chart displays the prevalence of different CD8+ T cell subgroups between the two groups, estimated by Ro/e. The subgroups favoring the Fibrosis+ LM are positioned above, whereas those favoring the Fibrosis− LM are positioned below. d The beeswarm and box plots depict the distribution of log2-fold differences in neighborhoods across various cell type clusters of CD8+ T cells, estimated by MiloR. The rightward positions indicate higher abundance in the Fibrosis+ LM, whereas the leftward positions indicate higher abundance in the Fibrosis− LM. e A heat map depicting the expression of marker genes across defined CD8+ T cell clusters. The color intensity reflects the average scaled gene expression. f A heat map via irGSEA visualizing the distribution of curated significant gene sets identified by robust rank aggregation across CD8+ T cells clusters. The number of asterisks in the grid’s upper half indicates the P value. g A Slingshot trajectory analysis of CD8+ T cell differentiation reveals two principal divergent trajectories. The cells are color-coded according to their pseudotime. h The density changes of CD8+ T cell subclusters along path 1 and path 2 are shown. i The two-dimensional plots showing the expression scores for four representative gene signatures in cells of paths 1 and path 2, respectively, along the inferred pseudotime. j The mIHC/IF images showing the positive expression of CXCL13_CD8_Tex. k The quantification of the density of CXCL13_CD8_Tex between Fibrosis+ LM and Fibrosis− LM, Wilcox rank-sum test.

The CXCL13_CD8_Tex cells exhibited upregulated exhaustion markers (TNFRSF9 and CTLA4) and CXCL13, indicative of impaired functionality (Fig. 3e). By contrast, STMN1_CD8_Tpro cells displayed elevated levels of proliferative markers (STMN1 and MKI67), and GZMK_CD8_Tem cells showed increased cytotoxicity markers (GZMK and KLRD1) and activation markers (IFNG). Consistent with the gene expression patterns, we performed irGSEA comparative analysis to evaluate the statistical significance of CD8+ T cell functional profiles (Fig. 3f). The STMN1_CD8_Tpro cells showed a significant upregulation of glycolysis, OXPHOS, NF-κB signaling and stress pathways, consistent with their mature and proliferative phenotype. The KLRB1_CD8_MAIT cells exhibited a significant upregulation of naive, NF-κB signaling and anti-apoptosis pathways, along with the downregulation of both senescence and chemokine receptor pathways. The GZMK_CD8_Tem cells displayed a marked upregulation of activation pathways but a downregulation of glycolysis, OXPHOS, NF-κB signaling and stress response pathways, suggesting their potential positioning at the opposite developmental end from STMN1_CD8_Tpro, CXCL13_CD8_Tex showed a significant upregulation of glycolysis and exhaustion pathways but a downregulation of the naive pathway, corresponding to their mature immunosuppressive phenotype. CD55_CD8_Trm demonstrated a significant upregulation of naive, glycolysis and OXPHOS pathways, consistent with their resident memory-like phenotype.

On the basis of the comprehensive functional characterization, supporting evidence from previous studies14,32,33,34 and the automatic selection by the Slingshot algorithm, GZMK_CD8_Tem was identified as the most biologically appropriate origin for trajectory reconstruction. The trajectory analysis identified two primary paths for CD8+ T cells originating from GZMK_CD8_Tem and progressing through CD55_CD8_Trm. Path 1 terminated in KLRB1_CD8_MAIT, whereas path 2 continued through CXCL13_CD8_Tex to STMN1_CD8_Tpro (Fig. 3g, h). The dynamic gene signature expression indicated that Path 2 exhibited heightened stress response and exhaustion signatures, although both paths showed decreased cytotoxicity signatures (Fig. 3i). Given the predominance of path 2 cells in the Fibrosis+ LM, CD8+ T cells in this TME context may be predisposed to exhaustion. Validation through mIHC/IF analysis confirmed the increased infiltration of the primary exhausted T cell subset, CXCL13_CD8_Tex, in the Fibrosis+ LM (Fig. 3j, k and Supplementary Fig. 5b, c). In summary, the TME of the Fibrosis+ LM exhibits a distinct immunosuppressive T cell landscape characterized by enriched Tregs and exhausted CD8+ T cells, potentially leading to enhanced immune suppression and exhaustion.

Macrophages displaying profibrotic phenotye in the TME of Fibrosis+ LM

To investigate myeloid populations in CRLM, myeloid cells were categorized into subsets including MKI67+ macrophages (MKI67_Macro), SPP1+ macrophages (SPP1_Macro), THBS1+ monocytes (THBS1_Mono), HSPA6+ macrophages (HSPA6_Macro), C1Q+ macrophages (C1Q_Macro), C1DC+ dendritic cells (C1DC_DC), LAMP3+ dendritic cells (LAMP3_DC), CLEC9A+ dendritic cells (CLEC9A_DC) and FCGR3B+ neutrophils (FCGR3B_Neutrophil) (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 10). The Ro/e and MiloR analyses showed higher proportions of THBS1_Mono, SPP1_Macro and MKI67_Macro in the Fibrosis+ LM, whereas HSPA6_Macro, CD1C_DC and FCGR3B_Neutrophil were more prevalent in the Fibrosis− LM (Fig. 4b–d). The statistical analysis revealed a significantly higher proportion of SPP1_Macro in the Fibrosis+ LM group compared with the Fibrosis− LM group (Supplementary Fig. 6a).

a A UMAP plot illustrating nine myeloid cell clusters across all samples, color-coded by cell type. b The bar plot illustrates the relative proportion of myeloid cell clusters in each sample from the Fibrosis+ LM and Fibrosis− LM. c The lollipop chart displays the prevalence of different myeloid cell subgroups between the two groups, estimated by Ro/e. The subgroups favoring the Fibrosis+ LM are positioned above, whereas those favoring the Fibrosis− LM are positioned below. d The beeswarm and box plots depict the distribution of log2-fold differences in neighborhoods across various cell type clusters of myeloid cell, estimated by MiloR. The rightward positions indicate higher abundance in the Fibrosis+ LM, whereas the leftward positions indicate higher abundance in the Fibrosis− LM. e A heat map depicting the expression of marker genes across defined myeloid cell clusters. The color intensity reflects the average scaled gene expression. f A heat map via irGSEA visualizing the distribution of curated significant gene sets identified by robust rank aggregation across macrophage as well as monocyte cells clusters. The number of asterisks in the grid’s upper half indicates the P value. g A heat map visualizing the distribution of curated significant gene sets identified by robust rank aggregation across DC cell clusters. The number of asterisks in the grid’s upper half indicates the P value. h A Slingshot trajectory analysis of macrophage as well as monocyte differentiation reveals one principal divergent trajectory. The cells are color-coded according to their pseudotime. i The density changes of macrophage subclusters along path 1 are shown. j The two-dimensional plots showing expression scores for seven representative gene signatures in cells of paths 1, along the inferred pseudotime. k A Slingshot trajectory analysis of DC differentiation reveals one principal divergent trajectories. The cells are color-coded according to their pseudotime. l The density changes of DC subclusters along path 1 are shown. m The two-dimensional plots showing expression scores for three representative gene signatures in cells of paths 1 along the inferred pseudotime. n The mIHC/IF images showing the positive expression of SPP1_Macro. o The quantification of the density of SPP1_Macro between Fibrosis+ LM and Fibrosis− LM group, Wilcox rank-sum test.

SPP1_Macro exhibited an elevated expression of profibrotic markers SPP1, FN1 and FBP1, previously associated with fibrotic macrophages29. C1Q_Macro showed an increased expression of complement system genes such as C1QA, C1QB and C1QC. The MKI67_Macro population exhibited upregulated proliferation markers STMN1 and MKI67 while displaying mixed characteristics of both SPP1_Macro and C1Q_Macro (Fig. 4e). This cluster was probably grouped owing to its highly expressed cell cycle-related genes and was therefore excluded from downstream trajectory analysis to avoid interference with the differentiation path inference. The HSPA6_Macro populations exhibited a high expression of heat-shock-protein-encoding genes, probably associated with the aforementioned tissue dissociation procedure35,36,37, and were consequently excluded from subsequent analyses. FCGR3B_Neutrophil demonstrated an enhanced expression of neutrophil maturation markers, including C5AR1 as well as neutrophil markers S100A8 and S100A937,38,39 (Fig. 4e). It is worth noting that because neutrophils typically contain low RNA levels, we further validated this cell population’s identity using multiple approaches. First, we compared the expression of established neutrophil markers (CXCR2, FCGR3B and CSF3R)37,38,39, which showed significantly higher expression in this subset than in other cell populations (Supplementary Fig. 7a–c). In addition, we assessed the signature scores of neutrophil using gene sets from three previous studies40,41,42 (Supplementary Table 11) via the AddModuleScore, which similarly demonstrated significantly higher scores in FCGR3B_Neutrophil compared with others (Supplementary Fig. 7d–f). Together, these consistent findings robustly support our initial annotation. To assess the functional enrichment significance in macrophages and monocytes, we conducted comparative analysis using irGSEA (Fig. 4f, g). SPP1_Macrophage showed a significant upregulation of angiogenesis pathways (Fig. 4f), consistent with their established proangiogenic function43. Similarly, LAMP3_DC exhibited a pronounced enrichment of immune activation pathways (Fig. 4g), matching their reported mature regulatory phenotype37,38,39,40,41,42.

According to previous studies13,44,45 and the automatic selection by the Slingshot algorithm, THBS1_Mono was selected as the progenitor population for developmental trajectory analysis. Pseudotemporal reconstruction revealed a predominant differentiation pathway, with macrophages and monocytes deriving from THBS1_Mono, transitioning through SPP1_Macro and ultimately maturing into C1Q_Macro (Fig. 4h, i). Notably, phagocytic activity scores exhibited a transient peak followed by a rapid decline along this developmental trajectory (Fig. 4j). Consistent with previous reports18,44,46 and the automatic selection by the Slingshot algorithm, LAMP3_DC was identified as the terminal population in the developmental trajectory analysis. The DC differentiation trajectories revealed a single path starting at CLEC9A_DC, passing through CD1C_DC and culminating at LAMP3_DC (Fig. 4k, l), with increased activation, migration and tolerance signatures along this trajectory (Fig. 4m).

The independent verification through mIHC/IF analysis confirmed the enhanced infiltration of the profibrotic macrophage subset, SPP1_Macro, in the Fibrosis+ LM (Fig. 4n, o and Supplementary Fig. 6b, c). Overall, the TME of the Fibrosis+ LM was characterized by the presence of profibrotic macrophages, reduced complement activation in macrophages and decreased numbers of antigen-presenting DCs.

TME of Fibrosis+ LM characterized by the presence of profibrotic and ECM-remodeling fibroblasts

In this study, fibroblasts were classified into three subsets: versican (VCAN)+ matrix fibroblasts (VCAN_eCAF), MYH11+ myofibroblasts (MYH11_myoCAF) and NRXN1+ peripheral nerve-like fibroblasts (NRXN1_pnCAF) (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Table 12). An analysis using Ro/e and MiloR indicated that the Fibrosis+ LM exhibited higher proportions of VCAN_eCAF, whereas the Fibrosis− LM showed increased levels of MYH11_myoCAF (Fig. 5b–d). The statistical analysis revealed distinct differences in cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF) subtype distribution between fibrosis groups: VCAN_eCAF were significantly enriched in Fibrosis+ LM samples, whereas MYH11_myoCAF predominated in Fibrosis− LM samples (P < 0.05; Supplementary Fig. 8a).

a A UMAP plot illustrating three CAF clusters across all samples, color-coded by cell type. b The bar plot illustrates the relative proportion of CAF clusters in each sample from the Fibrosis+ LM and Fibrosis− LM. c The lollipop chart displays the prevalence of different CAF subgroups between the two groups, estimated by Ro/e. The subgroups favoring the Fibrosis+ LM are positioned above, whereas those favoring the Fibrosis− LM are positioned below. d The beeswarm and box plots depict the distribution of log2-fold differences in neighborhoods across various cell type clusters of CAF, estimated by MiloR. The rightward positions indicate higher abundance in the Fibrosis+ LM, whereas the leftward positions indicate higher abundance in the Fibrosis− LM. e A heat map depicting the expression of marker genes across defined CAF clusters. The color intensity reflects the average scaled gene expression. f A heat map showing the functional pathways activated in different CAF subclusters using GO analysis. The heat map is based on scaled gene signature scores. g A Slingshot trajectory analysis of CAF differentiation reveals one principal divergent trajectories. The cells are color-coded according to their pseudotime. h The density changes of CAF subclusters along path 1 are shown. i The pivotal upregulated genes and surface proteins orchestrating this regulatory process along the inferred pseudotime, estimated by GeneSwitches. j The biological processes triggered to orchestrate this regulatory process along the inferred pseudotime, estimated by GeneSwitches. k The changes of common matrix genes along path 1 are shown. l The mIHC/IF images showing the positive expression of VCAN_eCAF. m The quantification of the density of VCAN_eCAF between the Fibrosis+ LM and Fibrosis− LM groups, Wilcox rank-sum test.

Using the AddModuleScore to evaluate signature scores of different CAF subtypes from previous studies (following Liu et al.’s method47, see Supplementary Table 13), we performed a classification of the three identified CAF populations in this study. Notably, VCAN_eCAF exhibited the highest ‘Liver1_mCAF’ signature scores, consistent with the established matrix-producing CAF phenotype48 (Supplementary Fig. 8b). This subtype notably expresses elevated levels of genes encoding ECM proteins such as LUM, VCAN and DCN, highlighting its strong ECM protein secretion capability (Fig. 5e). To more accurately characterize the functional properties of fibroblasts, we performed a gene ontology (GO) analysis using limma v3.52.4 to evaluate pathway activities14, with an adjusted P value threshold of <0.05 considered statistically significant for identifying enriched pathways (Fig. 5f). The results further confirmed that VCAN_eCAF is significantly enriched in pathways related to ECM remodeling, including ‘ECM organization’ and ‘extracellular structure organization’. MYH11_myoCAF exhibited the highest scores for the ‘Pan-cancer1_CAF_myo(C1)’ signature, suggesting a myofibroblast phenotype49, consistent with its high expression of MYH11 and MUSTN1 (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 8b). The functional enrichment analysis revealed that this subtype was significantly enriched in pathways related to muscle contraction and tissue repair (Fig. 5f). Although NRXN1_pnCAF represented a minor population, our study identified that it exhibited the highest ‘Pan-cancer1_CAF_PN(C7)’ scores, corresponding to peripheral nerve-associated CAFs (Supplementary Fig. 8b) as previously reported49. The GO analysis (Fig. 5f) demonstrated that NRXN1_pnCAF is enriched in pathways such as the ‘ensheathment of neurons’, consistent with its gene expression profile, further supporting its potential neurorelated characteristics.

Given the rarity and low abundance of NRXN1_CAF, we excluded this population from subsequent trajectory analysis to avoid potential interference with the differentiation inference. On the basis of previous studies47,50,51 and the automatic selection by the Slingshot algorithm, MYH11_myoCAF was selected as the progenitor population for developmental trajectory analysis. The developmental trajectory originated from MYH11_myoCAF and culminated in VCAN_eCAF, indicating that VCAN_eCAF represents an activated state (Fig. 5g, h). The GeneSwitches analysis identified key upregulated genes during the transition from MYH11_myoCAF to VCAN_eCAF, predominantly involving collagen family members (COL5A1, COL6A3 and COL10A1) and ECM regulators (VCAN, LUM, CTHRC1, EFEMP1, LTBP2 and MMP2)52, which orchestrated ECM reorganization (GO_EXTRACELLULAR_STRUCTURE_ORGANIZATION) and EMT (HALLMARK_EPITHELIAL_MESENCHYMAL_TRANSITION) through fibrillar collagen assembly53,54. The transition was further characterized by endoplasmic reticulum lumen expansion (GO_ENDOPLASMIC_RETICULUM_LUMEN), marked by IGFBP3, EFEMP1 and SFRP4, reflecting heightened protein processing to meet secretory demands55,56, along with lysosomal lumen activity (GO_LYSOSOMAL_LUMEN) driven by CTSK and MMP2, indicative of ECM degradation during remodeling57,58. Moreover, the inflammatory responses (HALLMARK_INTERFERON_ALPHA/GAMMA_RESPONSE) were integrated through interferon-modulating genes (CFH, ISLR and THY1), linking immune signaling with stromal reprogramming59,60. Collectively, these molecular features delineate the functional specialization of VCAN_eCAF in coordinating ECM remodeling, secretory adaptation and immune-stromal crosstalk (Fig. 5i, j). Key matrix genes such as COL1A1, COL1A2, COL3A1, COL12A1 and FN161 were found to be upregulated during the transition from MYH11_myoCAF to VCAN_eCAF (Fig. 5k).

Moreover, through mIHC/IF analysis, we independently confirmed the increased infiltration of VCAN_eCAF in the Fibrosis+ LM (Fig. 5l, m and Supplementary Fig. 8c, d). In conclusion, the TME of the Fibrosis+ LM is characterized by the presence of fibroblasts actively involved in profibrotic processes and ECM remodeling, underscoring their substantial role in shaping the TME in CRLM with Fibrosis+.

Malignant epithelial cells with a more activated and invasive phenotype identified in TME of Fibrosis+ LM

Copy number variation (CNV) analysis was performed across all epithelial cell populations, utilizing 500 T or NK cells, 500 plasma cells and 500 B cells as reference controls (Supplementary Fig. 9a). Compared with reference cells, notable CNV aberrations were detected in the majority of epithelial cells (Supplementary Fig. 9b, c). The subsequent classification identified two distinct epithelial subsets: malignant cells (MCs) and normal epithelial cells (NCs) (Fig. 6a). Based on the biological characteristics of our samples (derived from LM lesions), the observed NCs were restricted to two potential origins: hepatocytes or cholangiocytes. To clarify their identity, we used two approaches: examining the expression of hepatocyte markers (ALB, AFP and ARG1) and cholangiocyte markers (KRT8, KRT19 and SOX9)62,63,64 in NCs, and evaluating gene signature scores for hepatocytes and cholangiocytes using AddModuleScore with reference to a published single-cell RNA sequencing dataset of healthy liver tissue62 (Supplementary Table 14). The analysis revealed that these cells highly expressed cholangiocyte markers but showed negligible expression of hepatocyte markers (Supplementary Fig. 9d). Furthermore, NCs exhibited the highest scores for the ‘cholangiocyte’ signature, indicating a cholangiocyte-like profile (Supplementary Fig. 9e). Collectively, these findings suggested that the NCs were more likely to be of cholangiocyte origin. Notably, MCs in Fibrosis+ LM exhibited significantly elevated CNV scores compared with Fibrosis− LM (Fig. 6b). Comparative analysis of classical hallmarks of tumor biological signatures revealed that Fibrosis+ LM-derived MCs exhibited markedly higher scores for these traits (Fig. 6c). Cell cycle phase distribution analysis uncovered a progressive increase in the proportion of proliferating MCs (S and G2/M phases) within Fibrosis+ LM, indicative of heightened proliferative activity (Supplementary Fig. 10a). The CytoTRACE-based evaluation further identified significantly elevated cancer stemness properties in Fibrosis+ LM-derived MCs relative to Fibrosis− LM counterparts (Supplementary Fig. 10b). The pathway activity profiling via PROGENy revealed distinct oncogenic pathway activation patterns: Wnt, NF-κB and TNFα signaling pathways were predominantly enriched in Fibrosis+ LM-derived MCs, whereas Estrogen and Trail pathways showed preferential enrichment in Fibrosis− LM-derived MCs (Supplementary Fig. 10c).

a A UMAP view of MCs and NCs (top) and cell density (bottom) demonstrating the distribution between Fibrosis+ LM and Fibrosis− LM. High relative cell density is shown as bright magma. b The violin plot compared the CNV scores of MCs between Fibrosis+ LM and Fibrosis− LM, Wilcox rank-sum test. c A heat map illustrating the expression profiles of curated gene signatures in MCs between the Fibrosis+ LM and Fibrosis− LM. The heat map is based on scaled gene signature scores, Wilcox rank-sum test, P value: **≤0.01, ***≤0.001. d A bar chart displaying the Augur scores of cell types across all cell clusters. The length of each bar indicates the Augur score, with longer bars indicating a stronger association with the Fibrosis+ phenotype. e Cellchat compares the total number of interactions and interaction strength of the inferred cell–cell communication networks between Fibrosis+ LM and Fibrosis− LM. f A heat map showing the contribution of signals (signaling pathways or LR pairs) to cell groups in terms of the overall signaling between Fibrosis+ LM and Fibrosis− LM, estimated by Cellchat. g The two-dimensional plots showing the incoming and outgoing interaction strengths for each of the cell types between Fibrosis+ LM and Fibrosis− LM. h The signaling changes of VCAN_eCAF from Fibrosis− LM to Fibrosis+ LM, estimated by Cellchat. i The significantly upregulated or downregulated LR pairs involved in ‘COLLAGEN’ signaling between VCAN_eCAF and other cells, such as MYH11_myoCAF, endothelial cells and MCs, estimated by iTALK. j, k The significantly upregulated or downregulated LR pairs in all signaling pathways between VCAN_eCAF and other cells, including T cells (j) and myeloid cells (k), estimated by iTALK.

The pseudotime trajectory reconstruction delineated developmental paths from NCs to Fibrosis+ LM-derived MCs versus Fibrosis− LM-derived MCs (Supplementary Fig. 10d). The transcriptomic profiling along these trajectories demonstrated the notable upregulation of Wnt pathway-related genes specifically in Fibrosis+ LM-derived MCs (Supplementary Fig. 10e). Collectively, these findings indicate that Fibrosis+ LM-derived MCs exhibit distinct molecular characteristics from Fibrosis− LM-derived MCs, displaying enhanced malignant potential potentially driven by the Wnt pathway activation. The therapeutic targeting of this pathway may represent a strategic approach for Fibrosis+ LM management.

VCAN_eCAF playing a potential role in reshaping the TME of Fibrosis+ LM

Using the Augur algorithm, VCAN_eCAF was identified as one of the most transcriptionally responsive cell types to the Fibrosis+ (Fig. 6d), followed by MYH11_myoCAF and MCs. A comparative analysis of the key fibroblast subpopulations revealed distinct characteristics and functional states. MYH11_myoCAF, enriched in nonfibrotic regions (Fibrosis− LM) and expressing smooth muscle-associated genes (MYH11 and MUSTN1), may represent a progenitor and resident state primarily associated with structural and contractile functions. By contrast, VCAN_eCAF, substantially expanded in fibrotic regions (Fibrosis+ LM) and highly expressing core ECM genes (LUM, VCAN and collagens), may constitute an activated, terminal state that dominates the pathological ECM remodeling (Fig. 5a, f, k). Critically, the developmental trajectory analysis demonstrated that MYH11_myoCAF serve as the precursor population differentiating into VCAN_eCAF under profibrotic stimuli (Fig. 5g, h). Given the dominant enrichment of VCAN_eCAF in fibrotic lesions and their direct role as the primary effector cells executing pathological ECM deposition, subsequent analyses focus on elucidating the mechanisms by which this subpopulation drives fibrosis. To deepen our understanding of VCAN_eCAF’s role within the TME of the Fibrosis+ LM, we examined the complex network of intercellular communication. Compared with the Fibrosis− LM, there was a notable increase in both the frequency and intensity of interactions among various cellular subpopulations within the TME of the Fibrosis+ LM (Fig. 6e). VCAN_eCAF emerged as a primary source of signals within the broader signaling landscape (Fig. 6f). A comparative analysis with the Fibrosis− LM highlighted significant alterations in the strengths of both incoming and outgoing interactions, particularly affecting VCAN_eCAF (Fig. 6g). Moreover, the roles of endothelial cells, MYH11_myoCAF, SPP1_Macro and MKI67_Macro became more pronounced, indicating a more intricate network of cellular interactions within the TME of the Fibrosis+ LM (Fig. 6g). These observations, supported by our comprehensive analysis of transcriptional responsiveness (Fig. 6d), cell–cell communication networks (Fig. 6e–g) and pathway activation patterns (Fig. 5i, j), collectively demonstrate the potential involvement of VCAN_eCAF in shaping the TME dynamics of this cohort through its dual role as both a primary signal source and a key responder to fibrotic stimuli.

The further exploration of signaling variations in VCAN_eCAF between the low and Fibrosis+ LMs revealed a notable relevance of ‘COLLAGEN’, suggesting that VCAN_eCAF may influence the TME through the activation of collagen signaling pathways (Fig. 6h). Utilizing the iTALK algorithm, we identified specific LR pair alterations, highlighting enhanced interactions such as COL1A1–ITGB1, COL4A5–ITGA2 and COL5A2–DDR1 between VCAN_eCAF and other cell types including MYH11_myoCAF, endothelial cells and MCs within the Fibrosis+ LM (Fig. 6i). In addition, augmented LR partnerships such as ICOSLG–ICOS and TNFSF9–TRAF2 from VCAN_eCAF to various cell types including STMN1_CD8_Tpro, STMN1_CD4_Tpro, CXCL13_CD4_Tex, CXCL13_CD8_Tex, CTLA4_CD4_Treg, SPP1_Macro, MKI67_Macro, C1Q_Macro, CD1C_DC and LAMP3_DC were observed (Fig. 6j, k). These findings suggest that VCAN_eCAF may contribute to the progression of tumor fibrosis and regulate the infiltration of T cells and myeloid cells within the TME of the Fibrosis+ LM through these intricate LR interactions.

ST data displaying landscape of VCAN_eCAF in LM

The combined analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing and ST data enabled the characterization of spatial patterns across diverse cell subpopulations within the TME. To investigate the spatial relationship between tumor fibrosis and specific cell types, we examined six cases of CRLM: L1, L2, 19G29, 19G61, 19G63 and 19G81 (Fig. 7 and Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12). Next, we used CARD’s algorithm to analyze spatial colocalization patterns of identified cell types across tissue sections (Supplementary Figs. 13a, 14a, 15a, 16a, 17a and 18a). We initially focused on cell types involved in COLLAGEN signaling interactions (MCs, MYH11_myoCAF and endothelial cells) through iTALK-based single-cell RNA sequencing analysis, as well as the fibrotic macrophage subset SPP1_Macro65, examining their spatial relationships with VCAN_eCAF. Our analysis revealed the consistent colocalization of VCAN_eCAF with MCs, MYH11_myoCAF and SPP1_Macro across all sections (Supplementary Figs. 13b, 14b, 15b, 16b, 17b and 18b). By contrast, the endothelial cells exhibited no stable association and were therefore excluded from further analysis. The spatial distribution maps via CARD of VCAN_eCAF with MCs, MYH11_MyoCAF and SPP1_Macro were further illustrated (Fig. 7a, b and Supplementary Figs. 11a, b and 12a, b). More intriguingly, in samples L1 and L2, we observed an overlap between the spatial distribution of tumor fibrosis scores and the proportion of VCAN_eCAF (Fig. 7a–d). The spatial organization of VCAN_eCAF, as assessed by homotypic scoring, mirrored the tumor fibrosis scores (Fig. 7e, f). Furthermore, SPATA2’s spatial trajectory analysis revealed that among all examined cell types (including SPP1_Macro, MYH11_myoCAF and MCs), VCAN_eCAF was the only population that exhibited concordant spatial variation with tumor fibrosis scores in terms of cellular abundance (Fig. 7g–i).

a The spatial distribution of VCAN_eCAF, MYH11_myoCAF, SPP1_Macro and MCs proportions in sample L1, estimated by CARD. b The spatial distribution of VCAN_eCAF, MYH11_myoCAF, SPP1_Macro and MCs proportions in sample L2, estimated by CARD. c The spatial distribution of fibrosis scores in sample L1. d The spatial distribution of fibrosis scores in sample L2. e The spatial distribution of homotypic scores of VCAN_eCAF in sample L1. f The spatial distribution of homotypic scores of VCAN_eCAF in sample L2. g The spatial trajectory of fibrosis scores in sample L1, estimated by SPATA2. h The spatial trajectory of VCAN_eCAF proportions in sample L1, estimated by SPATA2. i The two-dimensional plots showing the changes in fibrosis scores and proportions of VCAN_eCAF, endothelial cells, MCs and MYH11_myoCAF along the spatial trajectory in sample L1, estimated by SPATA2. j The spatial trajectory of fibrosis scores in sample L2, estimated by SPATA2. k The spatial trajectory of VCAN_eCAF proportions in sample L2, estimated by SPATA2. l The two-dimensional plots showing the changes in fibrosis scores and proportions of VCAN_eCAF, endothelial cells, MCs and MYH11_myoCAF along the spatial trajectory in sample L2, estimated by SPATA2. m The spatial distribution of the COL1A1–ITGB1 LR pair in sample L1. n The spatial distribution of the COL1A1–ITGB1 LR pair in sample L2.

To validate the potential fibrosis-associated LR pairs identified via iTALK (Fig. 6i), we conducted the Spagene algorithm. We systematically evaluated multiple LR interactions (COL1A1–ITGB1, COL4A5–ITGA2 and COL5A2–DDR1) across all tissue sections (Fig. 7 and Supplementary Figs. 11–18). Although the expression of COL4A5–ITGA2 and COL5A2–DDR1 was detectable, their spatial colocalization patterns, which were quantified by the LR score using the Spagene algorithm (Supplementary Figs. 13c, d, 14c, d, 15c, d16c, d, 17c, d and 18c, d), were negligible. By contrast, the COL1A1–ITGB1 pair exhibited pronounced colocalization and visually overlapping spatial distributions with fibrosis scores (Fig. 7m, n and Supplementary Figs. 11m, n and 12m, n). Consistent with prior studies, COL1A1 is the most abundant collagen in the ECM and is widely involved in pathological processes such as fibrosis, TME remodeling and tissue sclerosis, playing a critical role in diseases such as liver fibrosis and cancer metastasis66. ITGB1, as a core member of the integrin family, mediates cell–ECM adhesion and regulates cell migration, proliferation and survival67. Its aberrant expression is strongly associated with tumor invasion and fibrosis progression. Numerous studies have confirmed that the COL1A1–ITGB1 signaling axis is a key pathway in ECM–cell interactions during fibrosis and cancer68,69, whereas other related pathways have relatively limited evidence. Collectively, these results provided spatial evidence supporting VCAN_eCAF’s involvement in tumor fibrosis via collagen-mediated signaling pathways within the TME of CRLM.

Potential mechanism linking VCAN_eCAF to tumor fibrosis in Fibrosis+ LM

Historically, hepatic stellate cells have been recognized as the principal mediators of ECM synthesis in the liver, pivotal in the development of tumor fibrosis. Previous studies70,71 have consistently shown that tumor cells can induce hepatic stellate cell activation, leading to phenotypic transformations resembling ECM remodeling observed in VCAN_eCAF. To further explore this phenomenon, we conducted a comparative analysis of significantly upregulated LR pairs between VCAN_eCAF and MCs within the Fibrosis+ LM (Supplementary Fig. 19a). This analysis highlighted a notable upregulation of FGFR1 in VCAN_eCAF, particularly within the Fibrosis+ LM (Supplementary Fig. 19b, c). Interestingly, the ligands for FGFR1, FGF23 and FGF3, were specifically upregulated in MCs (Supplementary Fig. 19c–e). Based on these findings, we hypothesize that upon tumor cell metastasis to the liver, the secretion of fibroblast growth factors such as FGF23 and FGF3 may stimulate the phenotypic transformation of CAF precursor cells into VCAN_eCAF. Subsequently, VCAN_eCAF contributes to a TME characterized by tumor fibrosis, promoting the accumulation of suppressive T cells and profibrotic myeloid cells through the activation of the collagen signaling pathway.

Discussion

This study investigates the clinical implications of tumor fibrosis in LM from patients with CRLM. We then dissected the TME heterogeneity of Fibrosis+ LM and Fibrosis− LM at the single-cell RNA sequencing level. Our key findings were validated through a range of multidimensional analyses, including ST and mIHC/IF analysis, all aimed at enhancing clinical decision-making.

Previous research has established a correlation between fibrosis and a T cell immunosuppressive milieu7. Our findings indicate a significant increase in classically immunosuppressive T cell subsets, notably CTLA4_CD4_Treg and CXCL13_CD8_Tex. Moreover, our study identified an accumulation of proliferative T cell populations such as STMN1_CD8_Tpro and STMN1_CD4_Tpro, which exhibit a stress-induced phenotype associated with immune checkpoint inhibition, potentially contributing to resistance against immunotherapy16. These observations suggest that the TME of Fibrosis+ LM presents a complex, multilayered T cell immunosuppressive environment. This complexity may hinder the direct enhancement of T cell-mediated antitumor responses, potentially leading to failures in systemic treatments and a higher rate of postoperative recurrence. Concurrently, our analysis of myeloid cells within the Fibrosis+ TME revealed a nuanced landscape. Previous studies have highlighted the fibrogenic properties of SPP1-positive macrophages65, findings consistent with our observation of a significant increase in SPP1_Macro within the Fibrosis+ LM. Together, these findings underscore the potent immunosuppressive characteristics of myeloid cells within the Fibrosis+ TME, which may impact both therapeutic strategies and patient outcomes adversely. Understanding these complex interactions between tumor cells, T cells and myeloid cells is crucial for developing effective immunotherapies and personalized treatment approaches for patients with Fibrosis+ LM.

Fibroblasts constitute a principal cellular component of the tumor stroma, demonstrating significant diversity and playing pivotal roles within the TME72,73. CAFs have been recognized as key drivers in the progression from tumor fibrosis to cirrhosis and HCC74. Studies have underscored the profibrotic phenotype of CAFs in cancer, contributing prominently to the establishment of a high-fibrotic TME75,76. Targeting these fibroblasts for antifibrotic therapies offers a promising strategy to reverse high-fibrotic TME, ultimately enhancing treatment efficacy and improving patient prognosis77. In this study, we identified a specific subgroup of CAFs characterized by high expression of VCAN. These CAFs also exhibited elevated levels of ECM-related genes, including LUM, COL1A1 and COL1A2, indicative of their activated state promoting tumor fibrosis. Notably, this subgroup of fibroblasts showed heightened responsiveness to the Fibrosis+ as a biological variable. A detailed analyses of cellular communication suggested that their activation played a pivotal role in reshaping the TME within the Fibrosis+ LM. Furthermore, our investigation into collagen signaling pathways implicated their regulatory influence on ligands interacting with T cells and myeloid cells within the TME, potentially exacerbating fibrosis. The spatial analysis revealed a colocalization of these VCAN-expressing CAFs with regions of intense tumor fibrosis, indicating their potential contribution to the high-fibrotic phenotype of the TME in Fibrosis+ LM. The FGFR signaling pathway, crucial for cellular processes such as proliferation and differentiation, has been implicated in various cancers78. Previous studies have highlighted the role of FGF–FGFR signaling in promoting fibrosis, with extensive expression observed at fibrotic sites71,79,80. Furthermore, we found that Fibrosis+ LM-derived MCs exhibit the specific upregulation of the Wnt signaling pathway. Previous literature has reported a correlation between ECM remodeling and the Wnt pathway. For instance, Liu et al.81 found that pancreatic cancer cells can sense ECM stiffness and activate the Wnt–β-catenin–TCF4 signaling pathway, leading to the upregulation of CLIC1 expression and ultimately promoting glycolysis-dependent tumor growth. Penny et al.82 constructed a minimally invasive orthotopic xenograft model to demonstrate that targeting the oncogenic Wnt–β-catenin signaling pathway disrupts ECM expression and inhibits the growth of adrenal cortical carcinoma. The study further validated the effective control of tumor burden by inhibiting the Wnt–β-catenin axis using the novel small molecule inhibitor Tegavivint. Zhang et al.83 reported that fibroblast growth factors may accelerate liver fibrosis by positively regulating Wnt signaling, which increases the production of ECM. The resulting increase in liver fibrosis could be a carcinogenic mechanism by which fibroblast growth factors promote NASH-driven HCC. Our study observed an increase in the interaction between FGF23 or FGF3 and FGFR1 receptor-ligands between MCs and VCAN-expressing CAFs, suggesting a mechanism by which MCs secrete fibroblast growth factors that enhance the activation of VCAN-expressing CAFs, thereby influencing the TME in Fibrosis+ LM. This suggests that targeting VCAN_eCAF may improve prognosis by remodeling the fibrotic microenvironment and inhibiting tumor cell responses to ECM remodeling, with the underlying mechanisms warranting further investigation.

Several limitations of the present study warrant consideration. First, its retrospective design precludes the establishment of causal relationships between variables, as confounding factors may have influenced the observed results. Future prospective cohort studies are essential to validate our findings more robustly. Second, challenges in obtaining an adequate number of single-cell samples may have introduced bias in the identification of cell types and transitional pathways.

In summary, this study utilized clinical data to establish a correlation between tumor fibrosis in LM and poor survival outcomes in patients with CRLM. Moreover, it preliminarily explored potential mechanisms underlying the formation of tumor fibrosis, highlighting a promising direction for targeting VCAN_eCAF in this patient population.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author (H.Z., pumc95zhao@126.com) on reasonable request.

Change history

21 November 2025

Corresponding Author Hong Zhao's email address has been added.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74, 229–263 (2024).

Chen, Q. et al. Association of preoperative aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index with outcomes and tumour microenvironment among colorectal cancer with liver metastases. Cancer Lett. 588, 216778 (2024).

TangW, R. enL. et al. Bevacizumab plus mFOLFOX6 versus mFOLFOX6 alone as first-line treatment for RAS mutant unresectable colorectal liver-limited metastases: the BECOME randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 3175–3184 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. CCL19-producing fibroblasts promote tertiary lymphoid structure formation enhancing anti-tumor IgG response in colorectal cancer liver metastasis. Cancer Cell 42, 1370–1385 (2024).

Henderson, N. C., Rieder, F. & Wynn, T. A. Fibrosis: from mechanisms to medicines. Nature 587, 555–566 (2020).

Tharp, K. M. et al. Tumor-associated macrophages restrict CD8+ T cell function through collagen deposition and metabolic reprogramming of the breast cancer microenvironment. Nat. Cancer 5, 1045–1062 (2024).

Ding, J. H. et al. Integrated analysis reveals the molecular features of fibrosis in triple-negative breast cancer. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 24, 624–635 (2022).

Herzog, B. H. et al. Tumor-associated fibrosis impairs immune surveillance and response to immune checkpoint blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 15, eadh8005 (2023).

Ke, M. Y. et al. Liver fibrosis promotes immune escape in hepatocellular carcinoma via GOLM1-mediated PD-L1 upregulation. Cancer Lett. 513, 14–25 (2021).

Bagaev, A. et al. Conserved pan-cancer microenvironment subtypes predict response to immunotherapy. Cancer Cell 39, 845–865 (2021).

Tajaldini, M. et al. Strategy of targeting the tumor microenvironment via inhibition of fibroblast/fibrosis remodeling new era to cancer chemo-immunotherapy resistance. Eur. J. Pharm. 957, 175991 (2023).

Tietscher, S. et al. A comprehensive single-cell map of T cell exhaustion-associated immune environments in human breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 14, 98 (2023).

Wang, F. et al. Single-cell and spatial transcriptome analysis reveals the cellular heterogeneity of liver metastatic colorectal cancer. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf5464 (2023).

Yang, J. et al. Single-cell transcriptomic landscape deciphers olfactory neuroblastoma subtypes and intra-tumoral heterogeneity. Nat. Cancer 5, 1919–1939 (2024).

Hafemeister, C. & Satija, R. Normalization and variance stabilization of single-cell RNA-seq data using regularized negative binomial regression. Genome Biol. 20, 296 (2019).

Chu, Y. et al. Pan-cancer T cell atlas links a cellular stress response state to immunotherapy resistance. Nat. Med. 29, 1550–1562 (2023).

Dann, E. et al. Differential abundance testing on single-cell data using k-nearest neighbor graphs. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 245–253 (2022).

Cheng, S. et al. A pan-cancer single-cell transcriptional atlas of tumor infiltrating myeloid cells. Cell 184, 792–809.e23 (2021).

Briseno, C. G. et al. Deficiency of transcription factor RelB perturbs myeloid and DC development by hematopoietic-extrinsic mechanisms. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 3957–3962 (2017).

Street, K. et al. Slingshot: cell lineage and pseudotime inference for single-cell transcriptomics. BMC Genomics 19, 477 (2018).

Cao, E. Y., Ouyang, J. F. & Rackham, O. J. L. GeneSwitches: ordering gene expression and functional events in single-cell experiments. Bioinformatics 36, 3273–3275 (2020).

Skinnider, M. A. et al. Cell type prioritization in single-cell data. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 30–34 (2021).

Jin, S. et al. Inference and analysis of cell-cell communication using CellChat. Nat. Commun. 12, 1088 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. iTALK: an R package to characterize and illustrate intercellular communication. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/507871 (2019).

Wang, Z. Y. et al. Single-cell and bulk transcriptomics of the liver reveals potential targets of NASH with fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 11, 19396 (2021).

Ma, Y. & Zhou, X. Spatially informed cell-type deconvolution for spatial transcriptomics. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 1349–1359 (2022).

Bäckdahl, J. et al. Spatial mapping reveals human adipocyte subpopulations with distinct sensitivities to insulin. Cell Metab. 33, 1869–1882 (2021).

Kueckelhaus, J. et al. Inferring histology-associated gene expression gradients in spatial transcriptomic studies. Nat. Commun. 15, 7280 (2024).

Liu, Q., Hsu, C. Y. & Shyr, Y. Scalable and model-free detection of spatial patterns and colocalization. Genome Res. 32, 1736–1745 (2022).

Sathe, A. et al. GITR and TIGIT immunotherapy provokes divergent multicellular responses in the tumor microenvironment of gastrointestinal cancers. Genome Med. 15, 100 (2023).

Liu, B. et al. Single-cell meta-analyses reveal responses of tumor-reactive CXCL13+ T cells to immune-checkpoint blockade. Nat. Cancer 3, 1123–1136 (2022).

Chen, Y. P. et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals regulators underlying immune cell diversity and immune subtypes associated with prognosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cell Res. 30, 1024–1042 (2020).

Zheng, L. et al. Pan-cancer single-cell landscape of tumor-infiltrating T cells. Science 374, abe6474 (2021).

Zheng, C. et al. Landscape of infiltrating T cells in liver cancer revealed by single-cell sequencing. Cell 169, 1342–1356.e16 (2017).

Pan, X. et al. Tumour vasculature at single-cell resolution. Nature 632, 429–436 (2024).

van den Brink, S. C. et al. Single-cell sequencing reveals dissociation-induced gene expression in tissue subpopulations. Nat. Methods 14, 935–936 (2017).

Hu, S. et al. TDO2+ myofibroblasts mediate immune suppression in malignant transformation of squamous cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Invest. 132, e157649 (2022).

Shi, Y. et al. Decoding the multicellular ecosystem of vena caval tumor thrombus in clear cell renal cell carcinoma by single-cell RNA sequencing. Genome Biol. 23, 87 (2022).

Zilionis, R. et al. Single-cell transcriptomics of human and mouse lung cancers reveals conserved myeloid populations across individuals and species. Immunity 50, 1317–1334.e10 (2019).

Ding, S. et al. Single-cell atlas reveals a distinct immune profile fostered by T cell–B cell crosstalk in triple negative breast cancer. Cancer Commun. 43, 661–684 (2023).

Liu, X. et al. Th17 cells secrete TWEAK to trigger epithelial–mesenchymal transition and promote colorectal cancer liver metastasis. Cancer Res. 84, 1352–1371 (2024).

Mei, Y. et al. Single-cell analyses reveal suppressive tumor microenvironment of human colorectal cancer. Clin. Transl. Med. 11, e422 (2021).

Zuyin, L. et al. Single-cell and spatial transcriptomics delineate the microstructure and immune landscape of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the leading-edge area. Adv. Sci. 12, e2412740 (2025).

Kang, K. et al. Homologous recombination deficiency in triple-negative breast cancer: Multi-scale transcriptomics reveals distinct tumor microenvironments and limitations in predicting immunotherapy response. Comput. Biol. Med. 158, 106836 (2023).

Hu, J. et al. Tumor microenvironment remodeling after neoadjuvant immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Genome Med. 15, 14 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Characterization of the tumour microenvironment phenotypes in malignant tissues and pleural effusion from advanced osteoblastic osteosarcoma patients. Clin. Transl. Med. 12, e1072 (2022).

Liu, K. et al. Fibroblast atlas: shared and specific cell types across tissues. Sci. Adv. 11, eado0173 (2025).

Zhu, G. Q. et al. CD36+ cancer-associated fibroblasts provide immunosuppressive microenvironment for hepatocellular carcinoma via secretion of macrophage migration inhibitory factor. Cell Discov. 9, 25 (2023).

Luo, H. et al. Pan-cancer single-cell analysis reveals the heterogeneity and plasticity of cancer-associated fibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment. Nat. Commun. 13, 6619 (2022).

Gao, Y. et al. Cross-tissue human fibroblast atlas reveals myofibroblast subtypes with distinct roles in immune modulation. Cancer Cell 42, 1764–1783 (2024).

Ma, C. et al. Pan-cancer spatially resolved single-cell analysis reveals the crosstalk between cancer-associated fibroblasts and tumor microenvironment. Mol. Cancer 22, 170 (2023).

Guvatova, Z. G. et al. Matrisome transcriptome dynamics during tissue aging. Life 14, 593 (2024).

Prakash, J. & Shaked, Y. The interplay between extracellular matrix remodeling and cancer therapeutics. Cancer Discov. 14, 1375–1388 (2024).

Sleeboom, J. J. F. et al. The extracellular matrix as hallmark of cancer and metastasis: from biomechanics to therapeutic targets. Sci. Transl. Med. 16, eadg3840 (2024).

Lee, T. H. et al. Fibroblast-enriched endoplasmic reticulum protein TXNDC5 promotes pulmonary fibrosis by augmenting TGFβ signaling through TGFBR1 stabilization. Nat. Commun. 11, 4254 (2020).

Paharkova-Vatchkova, V. & Lee, K. W. Nuclear export and mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum localization of IGF-binding protein 3 regulate its apoptotic properties. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 17, 293–302 (2010).

Zhao, P., Sun, T., Lyu, C., Liang, K. & Du, Y. Cell mediated ECM-degradation as an emerging tool for anti-fibrotic strategy. Cell Regen. 12, 29 (2023).

Zou, N., Liu, R. & Li, C. Cathepsin K+ non-osteoclast cells in the skeletal system: function, models, identity, and therapeutic implications. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10, 818462 (2022).

Jorgovanovic, D. et al. Roles of IFN-γ in tumor progression and regression: a review. Biomark. Res. 8, 49 (2020).

Zhao, H. et al. Inflammation and tumor progression: signaling pathways and targeted intervention. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 6, 263 (2021).

Liu, X. et al. Multiple fibroblast subtypes contribute to matrix deposition in pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 69, 45–56 (2023).

MacParland, S. A. et al. Single cell RNA sequencing of human liver reveals distinct intrahepatic macrophage populations. Nat. Commun. 9, 4383 (2018).

Andrews, T. S. et al. Single-cell, single-nucleus, and spatial RNA sequencing of the human liver identifies cholangiocyte and mesenchymal heterogeneity. Hepatol. Commun. 6, 821–840 (2022).

Aizarani et al. A human liver cell atlas reveals heterogeneity and epithelial progenitors. Nature 572, 199–204 (2019).

Hoeft, K. et al. Platelet-instructed SPP1+ macrophages drive myofibroblast activation in fibrosis in a CXCL4-dependent manner. Cell Rep. 42, 112131 (2023).

Li, X. et al. COL1A1: a novel oncogenic gene and therapeutic target in malignancies. Pathol. Res. Pract. 236, 154013 (2022).

Su, C. et al. Integrinβ-1 in disorders and cancers: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Cell Commun. Signal 22, 71 (2024).

Li, M. et al. Microenvironment remodeled by tumor and stromal cells elevates fibroblast-derived COL1A1 and facilitates ovarian cancer metastasis. Exp. Cell Res. 394, 112153 (2020).

Lin, C. et al. Single-cell discovery of the scene and potential immunotherapeutic target in hypopharyngeal tumor environment. Cancer Gene Ther. 30, 462–471 (2023).

Xu, H. et al. Cancer associated fibroblast-derived CCL5 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis through activating HIF1α/ZEB1 axis. Cell Death Dis. 13, 478 (2022).

Li, C. et al. FGF19-induced inflammatory CAF promoted neutrophil extracellular trap formation in the liver metastasis of colorectal cancer. Adv. Sci. 10, e2302613 (2023).

Bejarano, L., Jordāo, M. J. C. & Joyce, J. A. Therapeutic targeting of the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Discov. 11, 933–959 (2021).

Biffi, G. & Tuveson, D. A. Diversity and biology of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Physiol. Rev. 101, 147–176 (2021).

Affo, S., Yu, L. X. & Schwabe, R. F. The role of cancer-associated fibroblasts and fibrosis in liver cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 12, 153–186 (2017).

Bartoschek, M. et al. Spatially and functionally distinct subclasses of breast cancer-associated fibroblasts revealed by single cell RNA sequencing. Nat. Commun. 9, 5150 (2018).

Houthuijzen, J. M. et al. CD26-negative and CD26-positive tissue-resident fibroblasts contribute to functionally distinct CAF subpopulations in breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 14, 183 (2023).

Hauge, A. & Rofstad, E. K. Antifibrotic therapy to normalize the tumor microenvironment. J. Transl. Med. 18, 207 (2020).

Turner, N. & Grose, R. Fibroblast growth factor signalling: from development to cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 116–129 (2010).

Ye, C. et al. Single-cell and spatial transcriptomics reveal the fibrosis-related immune landscape of biliary atresia. Clin. Transl. Med. 12, e1070 (2022).

Xie, Y. et al. FGF/FGFR signaling in health and disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 5, 181 (2020).

Zheng, J. H. et al. A CLIC1 network coordinates matrix stiffness and the Warburg effect to promote tumor growth in pancreatic cancer. Cell Rep. 43, 114633 (2024).

Penny, M. K. et al. Targeting oncogenic Wnt/β-catenin signaling in adrenocortical carcinoma disrupts ECM expression and impairs tumor growth. Cancers 15, 3559 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. FGF9 recruits β-catenin to increase hepatic ECM synthesis and promote NASH-driven HCC. Adv. Sci. 10, e2301166 (2023).

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant nos. 2023YFC3403800 and 2023YFC3403804), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 82503985, 82141127 and 82371228), CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (grant no. 2021-I2M-C&T-B-057), the Non-profit Central Research Institution Fund of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (grant no. 2019PT310026) and Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (grant no. SZSM202011010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Z. and Q.C. designed research; Y.D., C.Y.G., X.M.L. and X.L. performed research; Y.D., C.Y.G., X.M.L. and X.L. analyzed data; and Y.D., C.Y.G. and X.M.L. made additional analyses for the revised manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (ID: B2023-431-01), and informed consent was obtained from all the patients. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work and in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Deng, Y., Guo, C., Liu, X. et al. Single-cell transcriptomic profiling reveals liver fibrosis in colorectal cancer liver metastasis. Exp Mol Med 57, 2517–2532 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-025-01573-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-025-01573-3