Abstract

The objective of this study was to identify the manufacturer of Hanji, Korean handmade paper widely used in conservation science. To achieve this, machine learning models utilizing attenuated total reflectance–infrared spectroscopy (ATR–IR) were developed to assess the robustness and effectiveness of the computed models. Principal component analysis (PCA), partial least squares–discriminant analysis (PLS–DA), decision tree (DT), and k-NN models were constructed using IR spectral data, with the spectral region between 1800 and 1500 cm⁻1 identified as the critical input variable through Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) scores. The transformation of the obtained spectra into second derivative spectra proved beneficial in this key spectral region, leading to significant improvements in model performance. Additionally, the application of DBSCAN for outlier detection was effective in refining the dataset, further enhancing the performance of the models. Specifically, the k-NN model, when applied to the selected variables and preprocessed with the second derivative transformation, achieved an F1 score of 0.92. These findings underscore the importance of focusing on the 1800–1500 cm⁻1 spectral range and applying outlier detection techniques, such as DBSCAN, to enhance the robustness and accuracy of the Hanji classification models by eliminating the influence of atypical data points.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The preservation and restoration of cultural heritage artifacts, particularly those made of paper, pose significant challenges due to their delicate nature and historical value. Due to its organic nature, paper cultural heritage is particularly vulnerable to the passage of time, requiring advanced technology and expertise for its handling [1].

Hanji, a traditional Korean handmade paper, serves as a substrate for writing, painting, and printing. Crafted from the bast fibers of one-year-old paper mulberry trees (Broussonetia kazinoki Siebold), Hanji holds significant cultural and historical value in Korean society. Known globally for its exceptional strength, Hanji is used not only in Korea but also in the restoration and conservation of paper-based cultural heritage materials worldwide. [2,3,4]. Despite the excellent strength and durability of Hanji, selecting appropriate materials for conservation purposes remains challenging due to variations in wood species, manufacturing processes, and chemical additives used in processes across different manufacturers.

Crafters commonly employ Hanji to repair tears and fill gaps in paper, manuscripts, paintings, and books. Holes and other areas of paper loss may be individually repaired using Hanji, wood pulp, or paper selected to closely match the original in terms of weight, texture, and color. When preserving paper-based cultural heritage, it is crucial to select conservation materials that closely match the composition of the original artifact. However, the diverse methods of Hanji production varying in wood species, manufacturing processes, and chemical additives pose a significant challenge. Despite the many advantages of Hanji, these variations make it difficult to determine which specific type of Hanji should be collected and used for conservation purposes, complicating the preservation process. Specifically, when considering with national treasures and other valuable cultural heritage items, the investigation of suitable conservation materials must be conducted using nondestructive methods [1]. Conservation scientists are often faced with significant challenges because only noninvasive methods are permitted for characterizing of paper cultural heritage. Thus far, most such investigations have been conducted using invasive or microdestructive analyses [5], often involving microsampling methods for fiber identification using polarized light microscopy or chemical spot testing, such as the Biuret test. The Biuret test utilizes aqueous copper (II) sulfate in a basic solution to detect proteins, evaluating the presence of gelatin [6, 7]. However, the nature of these tests imposes limitations on the types of objects that can be studied. Herein, with the objective of advancing the global conservation science industry and ensuring the professional management of mulberry fiber supplies, it is proposed to be crucial to promote the adoption of species and origin identification techniques that minimize fiber damage while incorporating scientific analysis.

Spectroscopic analysis, which investigates the interaction between specific wavelengths of light and materials, is a well-established non-destructive method for characterizing materials without causing permanent alterations. Infrared (IR) and near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy are particularly valuable in this regard, being widely used for the non-destructive evaluation of various materials, including paper. In recent years, there has been increasing interest in combining machine learning techniques with infrared spectroscopy to differentiate the manufacturers of paper materials for forensic and other purposes [7,8,9,10,11,12]. Hwang et al. [1] have employed principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical clustering to enhance the identification of manufacturing regions. Their findings demonstrated the effectiveness of using infrared spectral data to extract meaningful patterns related to the chemical composition and structural features of Hanji, a traditional Korean paper. Additionally, Jang et al. [13] explored the application of near-infrared spectroscopy in conjunction with multivariate statistical methods to classify Hanji based on the various raw materials used in its production. By utilizing classification algorithms such as partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA), support vector machines (SVM), and random forest (RF), the study achieved high classification accuracy, particularly when Hanji was categorized by the origin of the paper mulberry. Both PLS-DA and SVM achieved 100% accuracy, while RF achieved 98%, underscoring the potential of these methods for precise classification of Hanji based on its raw material composition.

The objective of this study was to explore the classification potential of Korean handmade paper (Hanji) using supervised machine learning models. Additionally, the study aimed to assess the impact of outlier detection and spectral data preprocessing on improving model performance, utilizing attenuated total reflectance–infrared spectroscopy (ATR–IR).

Materials and methods

Materials

The Hanji samples studied are shown in Table 1. The details of these samples are included in the Hanji reference book [2], which offers data on papermaking methods, pH values, mechanical properties (e.g., grammage, thickness, tensile strength, folding endurance), and color information related to Hanji. Samples made exclusively from paper mulberry were initially selected from approximately 200 available options. Subsequently, any samples containing color were excluded. Priority was given to those sourced from manufactures actively engaged in the production and use of Hanji. Although the paper mulberry utilized by these manufactures is consistent, it was hypothesized that variations might exist in species or manufacturing processes. Therefore, samples were selected to capture differences in the most commonly used species, as well as variations in cooking, bleaching, and mucilage formation methods employed by these manufactures.

Methods

Optical microscopy

To characterize the fiber of Hanji, the Graff “C” stain solution was prepared according to ISO 9184–4-1990. Then, a glass slide containing a fiber sample from each sheet of paper was prepared by applying the Graff “C” solution. The characteristics of these fiber samples were observed using optical microscopy (Hi-Scope, HS/300U, HANA Vision Co. Ltd., Korea).

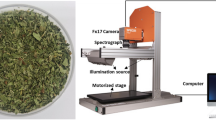

IR spectroscopy

The IR spectra of the Hanji samples over a wavenumber range of 4000–650 cm−1 were acquired using Fourier transform IR (FTIR) spectroscopy (FT/IR-6300, JASCO, Japan) with an ATR (Attenuated Total Reflectance) accessory at a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1. Average spectra were derived from 32 repeated scans of each material. For each Hanji sample, the IR spectra from ten samples were collected, resulting in a dataset comprising 180 (18 × 10) spectra.

Spectral preprocessing

The IR spectra were preprocessed using a Savitzky–Golay filter [14]. Specifically, the original spectra were transformed into second derivative spectra using a third-order polynomial with 21-point smoothing. The effectiveness of this preprocessing, as discussed by Hwang et al. [12, 15] and Kim and Eom [7] served to adjust the baselines of the spectra, amplify the peaks, and emphasize the differences between spectra. The preprocessed IR spectra in the range of 4000–650 cm−1 included 3477 input variables.

Dataset splitting

The datasets was divided into training and test sets at a ratio of 7:3 for classification modeling and performance evaluation. Stratified random sampling was used to ensure the split ratio was consistent across all classes. Additionally, a threefold cross-validation was employed during model training to ensure robustness and to avoid overfitting.

Density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (DBSCAN) for outlier detection

The DBSCAN [16, 17] algorithm was employed to detect outliers within the dataset, which was projected onto the orthogonal coordinate system of principal components (PCs). The parameters of DBSCAN clustering, specifically epsilon (eps) and the minimum number of samples (minPts), were determined empirically as 0.5 and 5, respectively. The parameter “eps” indicates the radius within which neighboring data points influence each other, and “minPts” denotes the minimum number of data points required for the formation of a cluster. A cluster was considered to have formed when at least five consecutive points were found within a distance of 0.5 from a given data point.

Principal component analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) was employed to analyze the IR spectral data of Hanji. High-dimensional IR data were projected onto a new orthogonal coordinate system composed of five PCs. The transformed data were visualized in a two-dimensional space, allowing for the exploration of patterns and structures inherent in the Hanji IR spectra. Consequently, the underlying structure of the data was revealed, important features were identified, and the interpretability of the dataset were enhanced.

PLS–DA

Partial least squares–discriminant analysis (PLS–DA) is a versatile discriminant technique. Its efficacy in modeling high-dimensional data has been extensively documented and has often outperformed the classical PCA approach coupled with linear discriminant analysis (PCA–LDA) [18]. Although PLS–DA operates similarly to PCA in projecting high-dimensional data into linear subspaces of explanatory variables, it employs a supervised learning approach, unlike the unsupervised approach of PCA. Consequently, the superiority of PLS–DA over PCA–LDA in constructing prediction models using high-dimensional datasets has become evident [19, 20].

The PLS–DA model can be formulated as a regression equation: Y = XB, where X is an n × p matrix representing n samples, with each sample characterized by a vector of p feature values [21]. Matrix Y is an n × k matrix that contains the class membership information of the samples, where k denotes the number of classes. Following the estimation of the regression matrix B using the PLS2 algorithm, the prediction for a new set of samples can be performed as follows: Ytest = XtestB.

The procedure for using the PLS–DA model can be summarized as follows:

-

1.

Data acquisition: IR spectral data were collected from the Hanji samples.

-

2.

Construction of Training Set: A training set consisting of IR spectral data and its corresponding class labels was established.

-

3.

Model training: The PLS–DA model was trained using the training set to classify the samples into different classes. This involved identifying the relationship between IR spectral data and the class labels and adjusting the model accordingly.

-

4.

Model validation: The trained PLS–DA model was validated using new IR spectral data to assess its classification accuracy and generalization performance.

-

5.

Interpretation of results: The classification results obtained from the PLS–DA model were interpreted to understand the discrimination between different classes based on their IR spectral data.

DT

The Decision Tree (DT) method [22,23,24], like other rule-based classification approaches, was employed to classify unknown data by recursively partitioning the data space based on the most significant variables. The model generates a tree structure, where each internal node represents a decision on a feature, each branch corresponds to an outcome of the decision, and each leaf node represents a class label. The process begins at the root node and proceeds down to a leaf node, where a decision is made.

To optimize the DT, the complexity parameter (cp), which controls the size of the tree and thus its complexity, was carefully tuned. The cp value determines the minimum reduction in the loss function required for any split to be attempted. A grid search was conducted to identify the optimal cp value within the range of 0.01 to 0.1, with the goal of preventing overfitting while maintaining model accuracy. The final model reflects the cp value that provided the most robust performance during threefold cross-validation.

k-NN

The k-nearest neighbors (k-NN) method, similar to Mahalanobis' generalized distance approach, was utilized to classify unknown data by assessing their proximity to previously categorized samples (Fix and Hodges 1952 [25]; Cover and Hart 1967 [26]. The class of an unknown sample is determined based on the classes of its k nearest neighbors, where each of the k nearest training samples contributes a vote for its respective class. The sample is then assigned to the category that receives the majority of votes. Therefore, selecting the appropriate k value, representing the number contributing to the classification decision, is critical [27]. Leveraging the proximity of samples and the majority voting principle, k-NN provides a straightforward and adaptable classification approach The optimal k value was identified through a grid search within the range of 1 to 9, focusing on odd numbers.

Variable importance measures

The variable importance in projections (VIP) metric from the PLS-DA model, introduced by Wold et al. [28], is often referred to as the VIP score [29]. This metric is designed to summarize the importance of each variable \(j\) as indicated by \(w\) across all components. The VIP score \({v}_{j}\) is defined as follows:

In this context, \({SS}_{a}\) is the sum of the squares explained by the \(a\) th component. The \({v}_{j}\) weights quantify the contribution of each variable according to the variance explained by each PLS component, where \({\left(\frac{{w}_{aj}}{{w}_{a}}\right)}^{2}\) represents the importance of the \(j\) th variable. The variance explained by each component can be calculated using the expression \({q}_{a}^{2}t\), as detailed in [29]; Therefore, \({v}_{j}\) can also be expressed as follows:

Evaluation metric

To evaluate the classification performance, the F1 score was employed, which is particularly suitable for imbalanced datasets. In a classification model, instances that are correctly identified as belonging to the positive class are called true positives (TP), while those correctly identified as negative class are true negatives (TN). Conversely, instances from the positive class that are incorrectly classified as negative are false negatives (FN), and those from the negative class misclassified as positive are false positives (FP) [30].

The F1 score is calculated as the harmonic mean of precision and recall, making it more reliable than accuracy in cases with class imbalances. Precision and recall are calculated as follows:

To address class imbalances, we employed a weighted F1 score, which considers the contribution of each class. The weight \({w}_{i}\) for each class i is calculated as:

where \({N}_{i}\) is the number of samples in class, and \({T}_{i}\) is the total number of samples. The weighted F1 score is then calculated by summing the F1 scores of each class multiplied by their respective weights:

This approach ensures that the performance of model is assessed accurately, even when dealing with imbalanced datasets [12]. All data processing and classification were conducted using the R statistical software (R Core Team, ver. 4.4.1, Auckland, New Zealand).

Results and discussion

Optical microscopy

Figure 1 shows optical micrographs of Mulberry fibers extracted from Hanji stained with the Graff “C” solution. However, using optical imagery alone, there is insufficient evidence for identifying either materials or manufacturers. Consequently, advanced discriminant analysis is necessary to develop methods for investigating Hanji used in conservation science. After staining with the Graff “C” solution, the samples revealed a wine-red color with violet hues, characteristic of bast fibers, in all eight types of collected samples. Another important feature of mulberry fibers, the presence of thin transparent membranes, is shown in Fig. 1. This property is typical of paper mulberry, and has previously been observed by Ilvessalo-Pfäffli and Marja-Sisko [31]. In summary, although comprehensive characterization was feasible using optical imagery, its application to differentiation or identification tasks are limited.

IR spectral characteristics

Figure 2 shows the infrared (IR) spectral characteristics of the Hanji samples. In the original spectra (Fig. 2a), the characteristic peaks observed in the range of 3600–3300 cm−1 were attributed to OH groups present in wood and paper materials [32]. Additionally, peaks ranging between 2890 and 2780 cm−1 were assigned to CH stretching, indicating the symmetrical stretching of C–H bonds in CH, CH2, and CH3 [33]. Distinct spectral signatures observed from 1647 to 1635 cm−1, 1430–1416 cm−1, and 1200–900 cm−1 were attributed to the absorbed water [34], CH2 bending of cellulose [35], and cellulose fingerprint regions [36], respectively.

In the corresponding second derivative spectra (Fig. 2c), each peak was amplified, and the baseline was corrected. Through the transformed spectra, the peaks at 1800–1300 cm−1 region were multiplied to separate any overlapping spectra (Fig. 2b and d). The peaks at 1508 cm−1 were assigned to aromatic skeletal vibration in lignin [37]; those at 1466–1460 cm−1 to amorphous cellulose [38]; those at 1374 cm−1 to C–H deformation vibrations in cellulose and hemicellulose [39]; and those at 1318 cm−1 to CH2 rocking in crystalline cellulose [40]. However, spectral regions considered to be noise, such as the range of 4000–1800 cm⁻1, were also amplified. The IR spectra include data that may be noisy or irrelevant for effective characterization. Excess input variables can considerably elevate the computational cost of the model [1, 12]. These regions contribute to decreased interpretability and effectiveness in model building.

PCA and outliers

Figure 3 shows the score plots corresponding to the first two PCs derived from Hanji IR datasets. Figure 3a, b present the PC score plots of the original and second derivative spectra, respectively. As shown in Fig. 3a, the data points from some of the samples are mixed, forming a unified cluster. However, after preprocessing the spectral data into second derivative spectra, the large cluster is subdivided into several smaller groups along the PC1 axis (Fig. 3b). While no dramatic improvements in clustering performance were observed, the subdivision of data points into smaller clusters, such as C1, C2, and C3, suggests that spectral preprocessing may enhance the separation of samples. This observation implies that during spectral preprocessing, the signal amplification may contribute to a more nuanced differentiation of the data. The differentiation of data classes in Hanji samples corresponded to PC1 in Fig. 3b. PC1 explains 61.9% of the data variation, while PC2 explains 6.3% of the variation in PC score plots of second derivative spectra for the region of 4000–650 cm−1.

Figure 3c indicates the corresponding PC loadings on second derivative spectra in the range of 4000–650 cm−1. PCs were derived from linear combinations of various variables, with the loadings indicating the influence of variables on each PC. The loadings reveal that the contribution of the allocated data points along the PC1 axis is attributed to carbonyl absorptions at 1760, 1720 [1], and 1554 cm−1 [7], as well as lignin absorption at 1595 [12] and 1508 cm−1. However, the IR spectra spanning from 4000 to 650 cm−1 encompass 3477 input variables, including zero-filled points, such as the regions from 4000 to 1800 cm−1. Excessive input variables are a primary factor contributing to the computational cost of the model [12] as mentioned above. Consequently, to enhance the interpretability and robustness of models, it is necessary to reset the range of input variables. Furthermore, as illustrated in Fig. 3d, the contributions of PC2, PC3, PC4, and PC5 were not substantial, further supporting the need for refining the variable range to enhance model performance.

The clustering results of DBSCAN on the original derivative IR spectra of Hanji samples were visualized in PC score plots (Fig. 4). However, in the case of the second derivative spectra, no outlier data points were identified. DBSCAN identified a total of 14 data points as outliers from the IR spectra of Hanji samples, including four from J1, two from A, M1, and H1, and one from each of M2, M4, H2, and Y1, respectively. These outliers did not belong to any cluster and were spatially located far from the other clusters. This significantly contributes to enhancing the clustering and classification performance of models [17]. The effectiveness of DBSCAN for outlier detection on IR spectral data was confirmed by comparing the performance of models constructed with datasets both containingand excluding outliers in the discriminating of Hanji.

PLS–DA

Figure 5 shows the PLS–DA score plots based on IR spectra of Hanji samples in the regions of 4000–650 cm−1. The outliers detected using the DBSCAN algorithm were not included. Similar to the PCA score plots shown in Fig. 3, the data points from some of the samples are mixed, forming a unified and large cluster. However, upon preprocessing the spectral data into their corresponding second derivative spectra, the large cluster becomes subdivided into several smaller groups along PLS component 1. PLS component 1 explains 61.5% of the data variation, while PLS component 2 explains 7.0% of the variation in PLS score plots of second derivative spectra in the region of 4000–650 cm−1. Through these results, the effectiveness of the second derivative preprocessing can be inferred.

The effect of spectral preprocessing and outlier detection on model performance is shown in Fig. 6. In the dataset containing outliers, the F1 score for the original spectra was 0.812, which improved to 0.835 after outlier removal. For the second derivative spectra, the F1 score increased from 0.850 with outliers included to 0.890 after outlier removal, demonstrating a significant enhancement. These results indicate that outlier removal is effective in improving model performance, especially when combined with spectral preprocessing. Consequently, resetting the range of input variables and employing robust outlier detection methods are critical for enhancing the performance of classification models.

Variable selection

The analysis of the PLS-DA model facilitates the identification of key features essential for class differentiation. However, when a large number of initial features are considered, the presence of orthogonal noise or irrelevant features that do not contribute to the classification can present challenges. Applying the classification model directly to the original dataset may result in distortions caused by these noise sources, leading to potential rotations in the original variable space. Consequently, the Pearson correlation coefficient (p(corr)) values of each variable in relation to the model components may be affected, causing some irrelevant features to appear falsely significant for class separation, as reflected in their VIP scores [41, 42]. Therefore, it is strategic to carefully select informative features when constructing a model to accurately distinguish between different sample subpopulations.

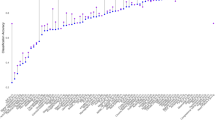

Figure 7 shows the VIP scores calculated for the second derivative spectra in the range of 4000–650 cm⁻1. As depicted in Fig. 7, the spectral regions within 1800–1500 cm⁻1 demonstrate significant variable importance. This observation aligns with the results of the PCA analysis shown in Fig. 3. Consequently, the spectral regions from 1800 to 1500 cm⁻1, which exhibit high importance based on the VIP scores, were selected for resetting the input spectral variables. The absorption peaks at 1760, 1720, 1620 [12], and 1554 cm−1 were assigned to carbonyl groups, and the peaks at 1595 and 1508 cm−1 were assigned to lignin in mulberry fibers.

By selecting this narrowed region, the number of input variables was reduced from 3477, representing the full spectral range, to just 277 variables. This represents a significant reduction in the number of variables. If the model performance is either improved or maintained with this reduced set, it would enhance the robustness of the model by simplifying the data while retaining critical information.

Model comparison

The classification performance of the PLS-DA model for Hanji classification was compared with that of the DT and k-NN models (Table 2). Notably, after applying second derivative preprocessing and reducing the number of input variables from 3477 to just 277, the performance of DT and k-NN models improved, with the k-NN model achieving the highest F1 score of 0.92 within the selected spectral region. However, despite the reduction in variables, the PLS-DA model did not exhibit any significant improvement in performance following variable selection. This outcome is likely attributable to the inherent characteristics of the models; PLS-DA operates as a linear classifier, whereas DT and k-NN are nonlinear classifiers. Consequently, the results suggest that variable reduction, in conjunction with second derivative preprocessing, is particularly beneficial for nonlinear classification models. Future research will focus on the advancement of nonlinear classification models and the development of more refined variable selection techniques.

Conclusion

This study effectively demonstrated the classification potential of Korean handmade paper (Hanji) using supervised machine learning models, including PLS-DA, decision tree (DT), and k-nearest neighbors (k-NN), based on attenuated total reflectance–infrared spectroscopy (ATR–IR). The application of DBSCAN for outlier detection significantly increased the purity of the dataset for class classification, leading to improved classification performance across the models. Notably, in the PLS-DA model, the F1 score increased from 0.812 to 0.835 after outlier removal in the original spectra, and from 0.850 to 0.890 in the second derivative spectra.

The calculation of Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) scores identified the spectral region between 1800 and 1500 cm⁻1 as critical, allowing for a strategic reduction in input variables from 3477 to 277. This reduction, coupled with second derivative preprocessing, further improved model performance. Among the models evaluated, the k-NN model, utilutilizing nonlinear classification, achieved the highest performance, with an F1 score of 0.92 when trained on the selected variables and processed using second derivative spectra.

These findings underscore the importance of VIP score-based variable selection, effective outlier detection, and spectral preprocessing in developing robust and effective Hanji classification models. Future research should focus on advancing nonlinear classification techniques and refining variable selection methods to enhance the applicability and precision of machine learning approaches in the conservation of cultural heritage materials like Hanji.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Hwang S-W, Park G, Kim J, Jeong M-J. Predictive modeling of traditional korean paper characteristics using machine learning approaches (Part 1): discriminating manufacturing origins with artificial neural networks and infrared spectroscopy. J Korea TAPPI. 2023;55(4):57–69. https://doi.org/10.7584/jktappi.2023.8.55.4.57.

Han B, Vilmont L-B, Kim H-J, Lavédrine B, Sakamoto S, Sablier M. Characterization of Korean handmade papers collected in a Hanji reference book. Herit Sci. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-021-00570-9.

Jeong M-J, Kang K-Y, Bacher M, Kim H-J, Jo B-M, Potthast A. Deterioration of ancient cellulose paper, Hanji: evaluation of paper permanence. Cellulose. 2014;21(6):4621–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-014-0455-4.

Jeong MJ, Bogolitsyna A, Jo BM, Kang KY, Rosenau T, Potthast A. Deterioration of ancient Korean paper (Hanji), treated with beeswax: a mechanistic study. Carbohydr Polym. 2014;101:1249–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.10.033.

Strlič M, Liu Y, Lichtblau DA, De Bruin G, Knight B, Winther T, et al. Development and mining of a database of historic European paper properties. Cellulose. 2020;27(14):8287–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-020-03344-x.

Wertz JH, McClelland AA, Mayer DD, Knipe P. Modeling chemical tests and fiber identification of paper materials using principal component analysis and specular reflection FTIR data. Heritage. 2022;5(3):1960–73. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage5030102.

Kim K-J, Eom T-J, Industry P. Classification of papers using IR and NIR spectra and principal component analysis. J Korea TAPPI. 2016;48(1):34–42.

Lee Y-J, Lee T-J, Kim HJ. Classification analysis of copy papers using infrared spectroscopy and machine learning modeling. BioResources. 2023;19(1):160–82. https://doi.org/10.15376/biores.19.1.160-182.

Kim K-J, Kim J-H, Park G, Jeong M-J. Predictive modeling of Korean traditional paper characteristics using machine learning approaches (Part 2): prediction of carbonyl content and analysis of variable importance using random forest. J Korea TAPPI. 2023;55(5):13–23. https://doi.org/10.7584/jktappi.2023.10.55.5.13.

Lee YJ, Kweon SW, Kim JH, Cha JE, Kang K-H, Kim HJ. Spectral preprocessing and machine learning modeling for discriminating manufacturing origins of mulberry bast fiber. J Korea TAPPI. 2023;55(5):61–74. https://doi.org/10.7584/jktappi.2023.10.55.5.61.

Lee YJ, Cha JE, Kang NY, Kweon SW, Kim HJ, Kang K-H. Unsupervised dimensionality reduction modeling for analyzing aging characteristics of Hanji. J Korea TAPPI. 2023;55(6):96–108.

Hwang S-W, Park G, Kim J, Kang K-H, Lee W-H. One-dimensional convolutional neural networks with infrared spectroscopy for classifying the origin of printing paper. BioResources. 2024;19(1):1633–51. https://doi.org/10.15376/biores.19.1.1633-1651.

Calssification options for Korean traditional paper.

Savitzky A, Golay MJ. Smoothing and differentiation of data by simplified least squares procedures. Anal Chem. 1964;36(8):1627–39.

Hwang S-W, Horikawa Y, Lee W-H, Sugiyama J. Identification of Pinus species related to historic architecture in Korea using NIR chemometric approaches. J Wood Sci. 2016;62(2):156–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10086-016-1540-0.

Reichert J. Automatic classification of communication signals using higher order statistics. Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, IEEE International Conference on: IEEE Computer Society; 1992. p. 221–4.

Hwang S-W, Chung H, Lee T, Kwak HW, Choi I-G, Yeo H. Investigation of NIR spectroscopy and electrical resistance-based approaches for moisture determination of logging residues and sweet sorghum. BioResources. 2023;18(1):2064–82. https://doi.org/10.15376/biores.18.1.2064-2082.

Kemsley EK. Discriminant analysis of high-dimensional data: a comparison of principal components analysis and partial least squares data reduction methods. Chemom Intell La Syst. 1996;33(1):47–61.

Lee LC, Jemain AAJ. Predictive modelling of colossal ATR-FTIR spectral data using PLS-DA: empirical differences between PLS1-DA and PLS2-DA algorithms. Analyst. 2019;144(8):2670–8.

Indahl UG, Martens H, Næs TJ. From dummy regression to prior probabilities in PLS-DA. J Chemom. 2007;21(12):529–36.

Sjostrom M, Wold S, Soderstrom BJPRiPI, Gelsema ES, Kanal LN. Feature extraction, classification, mapping. Elsevier: Amsterdam. 1989;486.

Quinlan JR. Induction of decision trees. Mach Learn. 1986;1:81–106.

Quinlan JR. Generating production rules from decision trees. IJCAI: Citeseer; 1987. p. 304–7.

Quinlan JR. C4. 5: programs for machine learning. Elsevier; 2014.

Fix E, Hodges JL. Discriminatory analysis: nonparametric discrimination, small sample performance. Air University, USAF School of Aviation Medecine; 1952

Cover T, Hart PJ. Nearest neighbor pattern classification. IEEE Trans Inf Theory. 1967;13(1):21–7.

Zhang S, Cheng D, Deng Z, Zong M, Deng XJ. A novel kNN algorithm with data-driven k parameter computation. Pattern Recognit Lett. 2018;109:44–54.

Wold S, Johansson E, Cocchi M. PLS: partial least squares projections to latent structures. 3D QSAR in drug design: theory, methods and applications. Kluwer ESCOM Science Publisher; 1993. p. 523–50.

Eriksson L, Johansson E, Kettaneh-Wold N, Wold SJU, Sweeden. Multi-and megavariate data analysis, Umetrics Academy. 2001.

Abraham S, Huynh C, Vu HJD. Classification of soils into hydrologic groups using machine learning. Data. 2019;5(1):2.

Ilvessalo-Pfäffli M-S. Fiber atlas: identification of papermaking fibers. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media; 1995.

Maréchal Y, Chanzy HJ. The hydrogen bond network in Iβ cellulose as observed by infrared spectrometry. J Mol Struct. 2000;523(1–3):183–96.

Xia J, Zhang J, Zhao Y, Huang Y, Xiong Y, Min SJ, et al. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics for the discrimination of paper relic types. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2019;219:8–14.

Polovka M, Polovková J, Vizárová K, Kirschnerová S, Bieliková L, Vrška MJ. The application of FTIR spectroscopy on characterization of paper samples, modified by Bookkeeper process. Vib Spectrosc. 2006;41(1):112–7.

Causin V, Marega C, Marigo A, Casamassima R, Peluso G, Ripani LJFSI. Forensic differentiation of paper by X-ray diffraction and infrared spectroscopy. Forensic Sci Int. 2010;197(1–3):70–4.

Barsberg S, Sanadi AR, Jørgensen HJ. A new density functional theory (DFT) based method for supporting the assignment of vibrational signatures of mannan and cellulose—analysis of palm kernel cake hydrolysis by ATR-FT-IR spectroscopy as a case study. Carbohydr Polym. 2011;85(2):457–64.

Horikawa Y, Hirano S, Mihashi A, Kobayashi Y, et al. Prediction of lignin contents from infrared spectroscopy: chemical digestion and lignin/biomass ratios of Cryptomeria japonica. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2019;188:1066–76.

Hajji L, Boukir A, Assouik J, Pessanha S, Figueirinhas JL, Carvalho ML. Artificial aging paper to assess long-term effects of conservative treatment. Monitoring by infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence (EDXRF). Microchem J 2016;124:646–56.

Li X, Wei Y, Xu J, Xu N, He Y. Quantitative visualization of lignocellulose components in transverse sections of moso bamboo based on FTIR macro-and micro-spectroscopy coupled with chemometrics. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2018;11:1–6.

Abidi N, Cabrales L, Haigler CHJCP. Changes in the cell wall and cellulose content of developing cotton fibers investigated by FTIR spectroscopy. Carbohydr Polym. 2014;100:9–16.

Favilla S, Durante C, Vigni ML, Cocchi MJC, Systems IL. Assessing feature relevance in NPLS models by VIP. Chemom Intell Lab Syst. 2013;129:76–86.

Galindo-Prieto B, Eriksson L, Trygg JJ. Variable influence on projection (VIP) for orthogonal projections to latent structures (OPLS). J Chemom. 2014;28(8):623–32.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support provided by the Ministry of Science and ICT (Information and Communication Technology) of the Korean government and the National Research Foundation of Korea (Grant No. RS-2023-00301889).

Funding

This research was supported by the Ministry of Science and ICT (Information and Communication Technology) of the Korean government and the National Research Foundation of Korea (RS-2023-00301889).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Yong Ju Lee; methodology: Yong Ju Lee, Seo Young Won; investigation: Yong Ju Lee, Seo Young Won, Seong Bin Park; funding acquisition: Yong Ju Lee; writing–original draft: Yong Ju Lee; writing–review and editing: Hyoung Jin Kim. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The consent for the publication of details and images in the manuscript are obtained from all participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, Y.J., Won, S.Y., Park, S.B. et al. Chemometric approaches for discriminating manufacturers of Korean handmade paper using infrared spectroscopy. Herit Sci 12, 373 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01460-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01460-6