Abstract

This study describes the process of digitally reconstructing the ancient Korean city of Suwon Hwaseong in 3D utilizing Historic Building Information Modeling (HBIM) resources to accurately represent its wooden architectural heritage. Previous 3D reconstructions of cultural heritage have often prioritized appearance or remained partially disassembled. However, our reconstruction method offers a comprehensive representation of the appearance and the internal structure of wooden architectural heritage, which can be suitable for restoration maintenance. To ensure accuracy in digital restoration, we collected and utilized administrative records and historical materials, including the geography, fortress walls, folk houses, and Haenggung (the temporary palace of the Joseon Dynasty)—drawing from the archive of the Korean Cultural Heritage Service’s management records and the 1796 manuscript “Uigwe: Royal Protocols of the Hwaseong Fortress” which documents the construction of the ancient city of Suwon Hwaseong. Extensive architectural records were used to generate HBIM data, which digitized historical records, documents, and drawings to accurately represent the complex layout of the wooden architectural heritage. For the folk houses that lacked design records and the fortress walls that retained their original shape, we performed a digital restoration-based façade modeling. These elements of the ancient city of Suwon Hwaseong were assembled into a 3D model using Unreal Engine (version 5.1.1) to digitally reconstruct the city and enhance its visual representation. The digital restoration content, which utilizes visual effects and precise rendering from a game engine, can be used for the restoration, repair, and maintenance of both appearance and internal structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 2003, UNESCO issued a “Charter on the Preservation of Digital Heritage” that stated that digital heritage is a computer-based resource of enduring value that should be “preserved for future generations” [1]. Currently, interest in digitized cultural heritage has increased [2, 3], and various fields, such as heritage management, maintenance, repair, and restoration, are digitizing cultural heritages [4, 5]. The fields of digital heritage make use of digital media with the objective of gaining a deeper understanding and ensuring the preservation of cultural and natural heritage. This approach allows for access to locations of cultural significance across a range of environments, periods, and locations, while also facilitating the perpetuation of cultural values and the preservation and repair of important objects. In order to achieve these goals, four specific requirements must be addressed. First, the digital heritage must provide users with insightful and interesting information about the cultural heritage, including specific descriptions and history. Second, it must consider user experience, delivering digital cultural heritage at a specification level that is appropriate for universal access (e.g., by reducing graphical processing while increasing digital expression).Footnote 1 Third, it must be easy to use, with intuitive and simple operations that allow users to obtain the information they need about the cultural heritage. Fourth, it should be realistic and historically authentic, showing the form of the building according to the period [6].

With recent technological advances, including integrated global positioning systems, advanced physical surveying based on advanced digital equipment, and three-dimensional (3D) scanning, the digitization of cultural heritage has become a popular approach to cultural heritage, opening up various cultural, technological, and academic applications [7, 8]. For example, this technological progress has led to several projects that digitally restored entire ancient cities. For example , ROME REBORN project realistically reconstructed the entire ancient city of Rome, incorporating buildings with varying levels of detail based on archaeological research. Several buildings included in the project were classified as Class I, that is, their location, identification, and design were known highly accurately; the designs are being used in archaeology and other fields, such as education and architecture, as representations of more than just their appearance [9]. However, as an appearance-focused project, ROME REBORN had its limitation, it is unable to provide comprehensive information about the structural and material details necessary for physical restoration. In modern times, Historic Building Information Modeling (HBIM) technologies are being used for the maintenance, management, and restoration of architectural heritage. HBIM is an integrated information model that includes three-dimensional (3D) geometric information of architectural heritage assets and incorporates non-geometric information, such as repair history over the life cycle. This makes it an essential tool in the field of cultural heritage, distinct from conventional Building Information Modeling (BIM), which primarily focuses on modern architecture.

While commercial BIM softwares were initially created for modern architecture and often focused on materials, such as stone and plaster, the HBIM approach addresses the complexities of traditional masonry-built heritage. This enables more seamless management of building elements, replacement timing, and restoration certification compared to existing document-based maintenance forms [10, 11]. However, accurately describing materials and joints is just one challenge in adopting HBIM. The difficulties extend to broader, more intricate issues related to the unique architectural characteristics, historical significance, and often unconventional construction techniques of heritage structures. These factors complicate the modeling and maintenance of such buildings as standard BIM techniques may not adequately capture the complex and nuanced qualities of historic architecture [12].

Although HBIM technology is advancing rapidly, it has not yet reached a development level that can support the full range of architectural heritage features, including building materials, architectural elements, structures, and joints. It makes a significant challenge when creating BIM models of architectural heritage in cultures, such as Korea, which are characterized by wooden construction with multiple joints.

The problems that arose in making a HBIM system for Korean wooden architectural heritage are listed as follows. First, wooden structures often have low durability as wood is vulnerable to various events, such as war and natural disasters. Even if the wood survives, its original appearance may change over time owing to the influence of elements, such as atmospheric agents and age, and with fixtures moving from their original positions due to natural and artificial displacement of the building. Wooden architectural heritage must be preserved by continuously repairing natural and artificial damage; therefore, digital restoration efforts require the collection and digitization of data from maintenance records and repair documents [13].Footnote 2 Second, the connections between wooden elements are difficult to represent digitally using conventional methods. Korean wooden architectural heritage comprises thousands or tens of thousands of parts of various types and shapes per building, and the structure of Korea’s traditional wooden architectural heritage is fundamentally different from that of modern or masonry architecture [14]. While modern and masonry elements are stacked and attached to form a single large surface, wooden buildings are constructed by assembling individual materials, such as columns, beams, and window frames. The smallest unit, bujae (wooden building element), comprises independent parts. Even elements that serve the same purpose may have slightly different shapes, materials, and seams depending on the region, use, and period. Consequently, a large amount of numerical and image-based data regarding building parts, proportions, colors, patterns, and grooves is required to represent these buildings [6, 15].

In order to create a digital heritage that satisfies the conditions of information, user experience, usability, and authenticity, the physical cultural assets must be digitized as they are. However, digitizing wooden architectural heritage requires extensive documentation of repair and conservation treatments and the characteristics of building elements. It seems difficult and time time-consuming task to assemble and operate this amount of data.

In this study, we present an HBIM method to accurately represent the appearance, the internal structure and member joints of wooden architectural heritage. We utilize this method to digitally restore the ancient city of Suwon Hwaseong, outputting a 3D model using the commercial Unreal Engine (version 5.1.1), which is used in gaming and animation [16,17,18]. In the process of building HBIM, we used the “Autodesk Revit” software, which is the most commonly used software in Korean BIM field; thus, it was easy to lay the work’s foundation. In addition, our content based on HBIM needs to represent internal structures and architectural elements need to be partially or fully disassembled. Because this involves more elements than the appearance-oriented 3D models typically used in digital content.We virtually restored an ancient city, Suwon Hwaseong as a case study because of the ample digitized data associated with it [19,20,21]. The Hwaseong Fortress was first listed by UNESCO as a reconstructed world cultural heritage site based on “Uigwe: The Royal Protocols of the Hwaseong Fortress,” a report published in 1801 that detailed the construction of Hwaseong and reconstruction of lost sections based on historical documents. Currently, these construction documents are digitally stored, making cross-referencing easy. While the final 3D model is intended for use by heritage professionals to facilitate the restoration, repair, and maintenance of the appearance and the internal structures, future iterations can be used as game assets or computer graphics (CG) in film and animation [22].

Methods

Our project proceeded in two phases. First, we created a pipeline to convert management records and historical data about Suwon Hwaseong’s wooden architectural heritage into usable HBIM data. Subsequently, we converted this HBIM data into a 3D model to be used for content [14, 23]. In several HBIM implementations, the 3D model is initially generated using non-invasive techniques, such as photogrammetry and LiDAR-based point cloud data collection, to prevent any potential damage to cultural heritage assets. These hardware-based methods, combined with advanced software capable of processing such data, are essential for creating HBIM models. This approach enables the precise digital preservation of both the appearance and the internal structures, ensuring accurate geometric representation without direct physical contact. However, since reports about the construction, repair, and dismantling of Suwon Hwaseong Temple exist from the time of its construction to the present, and it was restored through these records, it is possible to first build an HBIM model based on existing physical measurements and drawings. These records have been measured and managed as a national project, beginning from the Joseon Dynasty to the current day Republic of Korea, which implies that they have sufficient reliability. By building the HBIM based on these data, we aimed to realize details, such as the seams of wooden buildings, that would otherwise remain shaded in the 3D model.

Although HBIM models help maintain cultural properties, they are difficult to use as a source for various types of content, such as games, movies, and animation. Therefore, we decided to build the fictional Suwon Hwaseong as a game engine. Based on the HBIM model, which included detailed information about structural joints and historical repairs, we created a 3D content model and imported it into Unreal Engine. This conversion from HBIM to Unreal Engine allowed the model to be adapted for games and animations while maintaining its structural and historical accuracy. The resulting HBIM-based 3D content can be ported for various purposes, such as heritage management, public relations materials, movies, and animation. In the following sections, we describe the sources used in this process, the structures selected for inclusion in the model, and the processes of assembling the HBIM data and developing the final 3D model.

Sources

Our HBIM resource was based on documents, such as physical surveys and wooden architectural heritage repair reports, which detailed the appearance and the internal structures conditions of the Hwaseong structures. Currently, the records of preserved cultural properties in Korea are divided into three types—physical survey reports, repair reports, and physical survey and repair reports. The physical survey reports involve external surveys using measurement tools (Total station, laser scanner, camera, etc.), while the repair reports document simple repairs. The physical survey and repair reports describe findings during building dismantling for repairs, including previously unseen features, such as seams. We obtained data from the Suwon Hwaseong Fortress Agency’s Cultural Asset Facility Division and systematically organized them for use in HBIM.

To accurately identify the structures of Suwon Hwaseong, we analyzed the digitized survey drawings of Hwaseong and Haenggung, the temporary palace and the most prominent structure within the city. We assembled and organized these reference materials to facilitate element analysis and modeling [24,25,26,27,28], focusing on 14 wooden structures within Hwaseong and 34 survey drawings of Hwaseong’s temporary palace buildings. We analyzed these reports, documents, and drawings to extract necessary building element data, including the number, type, and characteristics of building elements.

Finally, we visited the site to capture images for the 3D mapping of the building’s model, which are difficult to obtain from existing documents and digital data. Moreover, we carefully examined the site for elements that differed from the documents and drawings, potentially due to weather and climate effects, to develop a careful strategy for the final HBIM.

Selected structures and features

Suwon Hwaseong was built as a capital by King Jeongjo of the Joseon Dynasty. It was a planned city, notably characterized by the large crisscrossing roads. Hwaseong’s main structures included Hwaseong Yusubu (the city), the Hwaseong Fortress, and Haenggung (the temporary palace). Ancient city of Suwon Hwaseong site is located in Paldal-gu, Suwon, Gyeonggi-do, South Korea, and the fortress was included in the UNESCO World Heritage List in December 1997.

Hwaseong Haenggung, a wooden cultural asset with construction and maintenance reports, from the time of construction to the present (and thus a fitting target for HBIM production), was a temporary palace for the kings of the Joseon Dynasty, and every king since Jeongjo had stayed there. Haenggung was usually used as the residence of Suwon’s president (busa) and military administrator (yusu). Furthermore, it was the largest of the temporary palaces built during the Joseon Dynasty. Thus, much like Suwon Hwaseong, the palace had political and military significance, making Haenggung an important heritage site that reveals the changes in political, military, and social culture in the late Joseon Dynasty. Excavation, restoration, and maintenance projects have recreated Haenggung as it was during the Joseon Dynasty.

Our digital restoration of the ancient city of Suwon Hwaseong included the geography/terrain of the city, the Hwaseong Fortress walls, and the wooden structures of the Hwaseong Haenggung and folk houses.

Tools and process for HBIM development

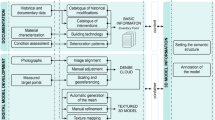

The fortress walls, folk houses, and geography/terrain were modeled and restored using Computer Graphics (CG), focusing on appearance (namely size and structural features), whereas Haenggung was modeled with HBIM for restoration purposes. The names of each software used for the restoration and the overall diagram of the data processing pipeline are shown in Fig. 1.

Geography/terrain modeling

To digitally recreate the historical and cultural environment of a city, one must use archival documents to extract the terrain data that can be used as the basis for the model. However, few historical records of Hwaseong’s geography were available. Given that the terrain around Suwon Hwaseong has not changed significantly over the last century, current terrain data and the 1917 cadastral survey map were used for modeling [29]. We extracted terrain data for the area around present-day Suwon Hwaseong using OpenStreetMap (Fig. 2). The mesh data from OpenStreetMap was used to create a basic mesh for implementing the landscape in Unreal Engine. This mesh served as a practical foundation and we did not focus on using a specific Digital Elevation Model (DEM).

The mesh data was used to create the base terrain, which was further modified according to computer-aided design (CAD) data and the 1917 cadastral survey map (Fig. 3). Hence, we created a 3D data model of the terrain around Suwon Hwaseong in 1917 (Fig. 4).

Hwaseong fortress walls

A model of the fortress walls is essential to recreate the historical and cultural environment of Hwaseong. Figure 5 shows that the fortress walls were stone structures, therefore, they can be replicated using conventional methods. We performed façade modeling based on the “Suwon Hwaseong Fortress Wall Precision Survey Report” [30,31,32]. This is a report about the precision survey using advanced equipment, such as 3D laser scanning and photogrammetry, from 2018 to 2020. According to the report, the Hwaseong Fortress Wall was composed of 62 sections divided into four areas based on the four gates. The length of a section was 100 m, measured from the lower end of the wall. The total length of the Suwon Hwaseong Fortress Wall was 5.74 km.

Source: Suwon Hwaseong Fortress Wall Precision Survey Report [30]

Sections of the Suwon Hwaseong Fortress Wall (left); Measurement drawing of Sect. 1 (right).

Wooden buildings

Archaeological evidence of folk houses in Hwaseong is not divided by period, and no records of the construction of folk houses exist. Therefore, we created a virtual representation of folk houses at the time of Hwaseong’s construction, performing façade modeling based on the city maps.

Conversely, given the detailed records available for Haenggung palace, as shown in (Supplementary Figs. 1–4), we reconstructed this wooden structure using HBIM-based content. This involved creating and populating a robust BIM data management tool using a plug-in for Autodesk Revit, which can manage large amounts of model data. After assembling our source documents, we divided each building into façades based on CAD drawings, carefully analyzing each building element. Figure 6 illustrates the source documents related to a reference portion of Haenggung—the Shinpungnu main gate and guard post—while Supplementary Fig. 5 depicts the Revit drawing for this building segment. The source documents include physical survey reports, repair reports, and combined physical survey and repair reports.

According to the architectural record “Uigwe,” all buildings in Suwon Hwaseong were designed in accordance with Yingzao Fashi, an East Asian technical treatise on architecture and craftsmanship [33]. However, discrepancies between the actual survey and drawings arise due to damage and aging repairs. To reconcile these differences, we conducted a field survey (Fig. 7).

Analysis of these resources yielded the summary values in Table 1 and the list of element types in Supplementary Table 1.

Overall, we identified 98,250 elements, including 2397 types, for all buildings in Hwaseong. To overcome the gaps in existing BIM systems, which are based on concrete buildings and do not follow the building element management system used by Korean cultural property management or repair organizations, we rearranged a compatible Industry Foundation Class (IFC) structure to represent each identified element using the Korea Foundation for Traditional Architecture and Technology’s building element classification system and reports [34, 35]. Based on the reorganized IFC structure, IFC codes were input into the cultural property absence management system, and elements were described according to the smallest measurement unit of Korean traditional buildings. Supplementary Table 2 shows some examples of how the IFC structure was rearranged to reflect the spatial and elemental characteristics of Korean architectural heritage, such as the foundation stone, wood characteristics, connections, and roof tiles (giwa). Hence, we created HBIM data for all the wooden architectural heritage in Haenggung. Figure 8 depicts the HBIM model for our reference section of the palace.

The research has shown that our HBIM model reached a Level of Detail (LOD) 4, as defined in the book by Antonopoulou and Bryan [36], accurately identifying the model’s type, materials, and dimensions. Furthermore, it serves as a “design intent” model for procurement and cost analysis.

The HBIM was delivered to the Korea Foundation for Traditional Architecture and Technology, which is responsible for Korean cultural heritage repair, and the Suwon Hwaseong Management Office, which is responsible for managing Suwon Hwaseong. They confirmed that it was consistent with the existing management materials and the current state of Suwon Hwaseong, and could be used for maintenance purposes [37].

Converting the HBIM model into a 3D model

The historically verified models and HBIM resources (comprising all the major wooden architectural heritage of Haenggung) created in this first phase were subsequently integrated into the Unreal gaming engine and converted into a cohesive 3D model. However, despite the convenience of HBIM data for maintenance and management, transferring these data directly into content is challenging, yielding incomplete and unusable digital cultural heritage with poor graphical representation. When 3D models are exported from BIM tools to the IFC format, they are exported as triangle polygon models. Unlike the rectangle polygon model used by current generation engines, to which these HBIM-based models will be imported, triangle polygon models have several unnecessary graphical elements, such as superfluous lines and planes, that introduce texture errors and make the models difficult to optimize. These lines and planes must be organized into quad meshes to naturally connect planes between element meshes and facilitate the application of texture coordinate (UV) maps. If this is not done, the texture may not fuse correctly with the model. While there are some automated features in modern software, substantial manual labor is required to ensure that the 3D content is visually pleasing and streamlined [38]. Therefore, we worked with a Computer Graphics (CG) expert, using the procedure outlined below to adapt the HBIM-based 3D model to the engine.

3D model cleanup

The cleanup process involved the following tasks:

-

1.

Checking for lamina (paired) and unnecessary faces (planes); objects that are strangely centered (e.g., empty space) may indicate unnecessary faces.

-

2.

Using the “Edges with Zero Length” feature to delete all the faces with zero distance between edges.

-

3.

Setting the model to the center coordinate (0, 0, 0) and using “Freeze and Reset Pivot.”

-

4.

Deleting unnecessary layers and history from the channel box to remove any remaining garbage data.

Figure 9 presents a comparison of the model before and after cleanup.

Modifying model vectors

The BIM software does not export some 3D models correctly. For example, repetitive patterns, such as roof tiles (giwa) in traditional oriental architecture, are exported in batches when using the “Family” feature, which is a default setting in Autodesk Revit. Figure 10 depicts this error, with the vectors of the tile objects stuck together in a straight line instead of being offset.

To correct this error and restore the original modeling file, additional cleanup was needed. Figure 11 compares the model before and after cleanup. It is noteworthy how the incorrectly exported roof tile shapes are corrected after cleanup.

UV cleanup

UV maps are two-dimensional (2D) unfolded depictions of the 3D modeling surface that define how textures should be applied to each face of the 3D objects. Before textures and materials can be applied to the cleaned-up model, the UVs of the object faces must be organized into a square frame that matches the texture resolution, allowing the texture to be applied deliberately and seamlessly to the object faces, producing realistic and detailed results. Figure 12 shows the UV map before and after cleaning. The UV maps of the tile model were organized into a square frame by removing redundant object faces.

Texture baking

During the modeling process, each building and element texture was created individually. They were later combined into a final object in the Unreal Engine. In the prototype of Suwon Hwaseong Reborn, nearly 10,000 parts per building were represented individually, however, this proved to be too much for the engine to manage. Consequently, in the final version, we improved rendering efficiency by converting high-polygon modeling to low-polygon modeling, yet maintained high-quality graphics by grouping building elements based on type. The following four texture maps were created from the HBIM data based on all the textures captured during site analysis—diffuse, roughness, metallic, and normal (Fig. 13).

Results and discussion

The processed 3D model, titled Suwon Hwaseong Reborn, is shown in Fig. 14.

The completed Suwon Hwaseong Reborn. a Digital reconstruction of the Hwaseong Haenggung palace, b Reconstruction of the entire city, c Partial disassembly of Sinpungnu, the Main Gate and Guard Post of Haenggung, d Full disassembly of the HBIM-based jaesil (ritual house), an annex to the Hwaryeongjeon Shrine

In this section, we assess the success of our HBIM development project regarding both the requirements of HBIM and the specific intended use-case for our project, namely to facilitate heritage maintenance, restoration prototyping, and rapid response to archaeological changes for wooden architectural heritage in Korea.

Realism/informative-ness

As shown in Figs. 14a and b, all sites in Suwon Hwaseong were reconstructed according to the archaeological evidence. Figure 14d, an overall anatomical view of the HBIM-based 3D model of jaesil (ritual house), shows that the HBIM-based 3D model was designed to represent parts, seams, materials, etc. in the same way, and with the same specificity, as the HBIM resource data.

User experience/ease of use

Digital heritage should be easily accessible to a wide range of users [6], regardless of their access to high-spec technologies. Thus, we stress-tested the program to ensure that the high-quality content is legible even on lower-spec systems. Our test demonstrated that a computer with an Intel I9-12900K processor and Nvidia RTX3080 graphics card stably maintained the model at over 60 fps. Additionally, an ASUS TUF Dash F15 FX517Z laptop with an Intel i5-12450H processor and Nvidia RTX3050 graphics card maintained the model at 25–30 fps in battery-saving mode. We expect to improve the optimization in the future.

We also conducted private internal testing and surveys with a total of 30 users. The results, summarized in Supplementary Table 3, revealed that “Suwon Hwaseong REBORN” is overall user-friendly; users particularly appreciated the functional quality of the content (50% agreed, and 36.67% strongly agreed). Its effectiveness in helping them understand cultural heritage was highly rated, with 33.33% agreeing and 60.00% strongly agreeing. It was also found to be easy to use owing to its clear representation of the targeted cultural heritage (26.67% agreed and 73.33% strongly agreed) and intuitive interface (40% agreed and 46.67% strongly agreed). However, some users experienced issues, such as motion sickness, which could be addressed, especially in the VR mode with an HMD. The addition of non-player characters (NPCs) walking the streets and showing historical footage to enhance the immersive experience were mentioned as positive improvements.

Support for heritage maintenance

This project had three achievements: (1) A historically accurate and detailed reproduction of shaded areas, such as seams that cannot be seen with traditional scanning tool-based modeling techniques (e.g., scan-to-BIM capabilities), (2) An adapted and flexible classification system based on Industry Foundation Class (IFC) structure rearrangement that allows for the addition of IFC codes to ensure that parts of a wooden structure can be accounted for, and (3) A dynamic model that allows for the granular manipulation of individual content elements so that only specific elements need to be modified or replaced when archaeological or architectural changes occur. The model also included maintenance records received directly from Suwon Hwaseong, therefore, adaptations could be performed immediately.

Our intended purpose is already being realized in the maintenance of this architectural heritage site. In Fig. 14c, a part of the Shinpungnu has been replaced, and because the repair history was identified through the HBIM system, it is also identified in the content. This shows how 3D content can digitally solve the time-consuming and expensive problem of traditional physical restoration, especially when parts have been replaced or restored incorrectly.

Conclusions

This study resulted in the development of an HBIM resource that uses the characteristics of wooden architectural heritage in Korea. The resource is capable of supporting heritage maintenance, restoration prototyping, and rapid response to archaeological changes. We used this resource to create digital heritage content that restored the appearance of Suwon Hwaseong, an ancient city with a variety of wooden architectural heritage, at the time of construction. This involved combining appearance-focused modeling of geography, stone cultural heritage, and folk houses with HBIM representation of the Haenggung palace. To create the HBIM resource, data were collected and analyzed for each element through repair history documents, survey reports, and drawings to understand the properties of these wooden structures (especially their connection points); IFC codes were assigned for wooden architectural heritage in Korea [39]. These data were used to model various types of HBIM and process the 3D model extracted from the HBIM’s IFC file to generate the final product—Suwon Hwaseong Reborn.

The digital restoration presented in this study is based on IFC files, which are an international standard for BIM software. As a result, making it can be applied to all cultural heritage properties where BIM is utilized. Suwon Hwaseong, designed and constructed based on the principles outlined in Yingzao Fashi, a technical treatise on architecture and craftsmanship compiled in 1103 during the Song Dynasty of China, served as the foundation for this restoration effort [33]. As the Yingzao Fashi system corresponds to a broader framework of East Asian architecture, the method presented in this study facilitates the creation of HBIM and HBIM-based 3D models for cultural heritage properties where it is applied [40]. The architectural heritage in the West has been extensively digitized using HBIM, forming the basis for cultural heritage management and restoration efforts by modeling the structural behavior of historical buildings through their constructive phase evolution, employing ontology-based frameworks for conservation, and integrating knowledge management practices [41,42,43]. Therefore, it is possible to build BIM models based on the HBIM and HBIM-based 3D model construction method advocated in this study, leveraging existing organizational frameworks and production methods.

The study’s methodology is based on BIM and has the potential to generate more detailed content resources for use in metaverses, such as the Horizon Europe European Metaverse [44], as it allows for a finer detail level than typical façade modeling.

This HBIM-based reconstruction of architectural and cultural heritage can be maintained and managed using BIM technology; it provides a dynamic experience that transcends physical limitations, such as time and space [45]. The second phase of physical restoration of Suwon Hwaseong has recently been completed and new physical and digital restoration projects are currently being initiated. Our HBIM and HBIM-based 3D content have been delivered to the Suwon Hwaseong Fortress Agency’s Cultural Asset Facility Division where they will be used for design verification and maintenance, and for developing online and offline promotional content for Suwon Hwaseong.

Contributions

The HBIM and content creation methodology developed in this study for traditional wooden architectural heritage sites has the potential to significantly advance cultural heritage preservation practices on a global scale. By providing a comprehensive digital restoration framework, our methodology can be adopted by cultural heritage organizations to enhance the preservation and maintenance of heritage sites. The digitization and visualization of paper-based maintenance management systems have the dual benefit of enhancing the efficiency of heritage site maintenance for professionals and promoting public engagement and awareness of cultural heritage for ordinary users. This innovative approach represents a substantial advancement in the domain of cultural heritage preservation and management.

Limitations

Notwithstanding the practical versatility of our method, it may be difficult to extrapolate it to all use cases. In particular, it requires materials with accurate data about multiple shaded areas, such as seams in wooden architectural heritage. Suwon Hwaseong was a suitable case study because of the existence of extensive records (especially Uigwe). Other wooden architectural heritage properties may not have sufficient data to create an HBIM resource. Additionally, certain technological developments can stall the application of our method. For example, recent Scan-to-BIM technologies are difficult to use for wooden architectural heritage, which makes it impossible to swiftly create HBIM. In some cases, dismantling a wooden heritage structure for repairs or collecting joint shapes using X-rays may not be feasible. When this occurs, creating joint shapes in HBIM requires informed speculation.

Given that the architectural elements of some works of ancient architectural cultural heritage are not adequately captured, creating an HBIM that accurately analyzes architectural styles across different eras and regions is challenging. While norms, such as those in the Yingzao Fashi system, exist, architectural cultural heritage exhibits nuanced differences in style, challenging the establishment of a universal standard. Therefore, constructing an HBIM of each architectural cultural heritage requires a detailed analysis of architectural styles and modifications to components, such as the IFC code and IFC structure, to ensure compatibility. This approach will ensure that the HBIM accurately reflects the unique features of architectural cultural heritage.

Future directions

Current work on Korean wooden architectural heritage is attempting to define the architectural style for each era such that unidentified seams can be inferred to some extent through the construction period, style, and region. Applying artificial intelligence to this effort could enable an HBIM to be created quickly, improving the performance of Scan-to-BIM for wooden architectural heritage and filling the gaps in available data. Additionally, future research should examine the possibility of automating the conversion of HBIM data into 3D models. In this study, the entire process of mesh conversion, data modeling, and UV cleaning was performed with the help of CG experts to ensure optimization and quality. Considering the lack of experience in HBIM and HBIM-enabled digital content creation for Korean wooden architecture, these processes were performed manually. However, data accumulation through future studies will enable partial or full automation.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Hwaseong Fortress Agency’s Cultural Asset Facility Division and Korea Cultural Heritage Administration, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the Hwaseong Fortress Agency’s Cultural Asset Facility Division and Korea Cultural Heritage Administration.

Notes

While high-quality graphics enhance the presentation of digital heritage over the Internet or as stand-alone software, these are not appropriate for all audiences.

To date, the maintenance, repair, and upkeep of cultural heritage has been conducted using handwritten reports, which has several disadvantages compared with digital data management. However, there has been a growing shift toward digitization, and the Korea Heritage Service aims to implement digital methods for all cultural heritage assets in Korea from 2021 to 2030.

Abbreviations

- BIM:

-

Building Information Modeling

- HBIM:

-

Historic Building Information Modeling

- 3D:

-

Three-Dimensional

- CG:

-

Computer Graphics

- DEM:

-

Digital Elevation Model

- CAD:

-

Computer-Aided Design

- IFC:

-

Industry Foundation Class

- 2D:

-

Two-Dimensional

- UV:

-

Texture Coordinates (U, V)

- LOD:

-

Level of Detail

- NPC:

-

Non-Player Characters

References

UNESCO. Charter on the preservation of digital heritage. 2003. https://www.unesco.org/en/legal-affairs/charter-preservation-digital-heritage. Accessed 12 Mar 2024.

Li R, Luo T, Zha H. 3D digitization and its applications in cultural heritage, EuroMED 2010. In: Ioannides M, Fellner D, Georgopoulos A, Hadjimitsis DG, editors. Notes in Computer Science. Berlin: Springer; 2010. p. 381–8.

Bijlani VA. Sustainable digital transformation of heritage tourism. In: 2021 IoT Vertical and Topical Summit for Tourism. IEEE Publications; 2021. https://doi.org/10.1109/IEEECONF49204.2021.9604839.

Adami A, Scala B, Treccani D, Dufour N, Papandrea K. HBIM approach for heritage protection: first experiences for a dedicated training. Int Arch Photogramm Remote Sens Spatial Inf Sci. 2023;XLVIII-M-2-2023:11–8.

Jia S, Liao Y, Xiao Y, Zhang B, Meng X, Qin K. Conservation and management of Chinese classical royal garden heritages based on 3D digitalization—a case study of Jianxin courtyard in Jingyi garden in fragrant hills. J Cult Herit. 2022;58:102–11.

Lee KH, Cho SH. 3D implementation of wooden structure system in Korea traditional wooden building. J Korea Multimed Soc. 2010;13:332–40 (in Korean).

Choi Y, Yang YJ, Sohn HG. Resilient cultural heritage through digital cultural heritage cube: two cases in South Korea. J Cult Herit. 2021;48:36–44.

Liao H-T, Zhao M, Sun S-P. A literature review of museum and heritage on digitization, digitalization, and digital transformation. In: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Humanities and Social Science Research (ICHSSR 2020). Atlantis Press; 2020. p. 473–6.

Dylla K, Frischer B, Müller P, Ulmer A, Haegler S. Rome reborn 2.0: a case study of virtual city reconstruction using procedural modeling techniques. In: 37th Annual International Conference on Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology (CAA). Colonial Williamsburg Foundation and The University of Virginia; 2010. p. 62–6.

López FJ, Lerones PM, Llamas J, Bermejo JG-G, Zalama E. A review of heritage building information modeling (H-BIM). MDPI Multimodal Technol Interact. 2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti2020021.

de Oliveira SG, Biancardo SA, Tibaut A. Optimizing H-BIM workflow for interventions on historical building elements. MDPI Sustain. 2022;14:9703.

Brumana R, Della Torres S, Previtali M, Barazzetti L, Cantini L, Oreni D, Banfi F. Generative HBIM modeling to embody complexity (LOD, LOG, LOA, LOI): surveying, preservation, site intervention—the Basilica di Collemaggio (L’Aquila). Appl Geomatics. 2018;10:545–67.

Shabani A, Kioumarsi M, Plevris V, Stamatopoulos H. Structural vulnerability assessment of heritage timber buildings: a methodological proposal. Forests. 2020;11:881.

Santos D, Sousa HS, Cabaleiro M, Branco JM. HBIM application in historic timber structures: a systematic review. Int J Archit Herit. 2023;17:1331–47.

Park JJ, Kim K, Ji SY, Jun HJ. Framework for BIM-based repair history management for architectural heritage. Appl Sci MDPI. 2024. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14062315.

Žurić J, Zichi A, Azenha M. Integrating HBIM and sustainability certification: a pilot study using GBC historic building certification. Int J Archit Herit. 2023;17:1464–83.

Lee JW, Lee JH, Kim JW, Kang KK, Lee MH, Goo BC. Time-based database for creation of Korean traditional wooden building. IEEE Digi Herit. 2015;2:213–4.

Lee JH, Lee JW, Kim JW, Kang KK, Lee MH. Virtual reconstruction and interactive applications for Korean traditional architectures. SCI-RES IT RSTI. 2016;6(1):5–14.

Memory G; 2014. https://memory.library.kr/main. Accessed 1 Nov 2023. (in Korean).

Suwon Cultural Foundation; 2011. https://www.swcf.or.kr/english/ 2011. Accessed 1 Nov 2023.

Suwon City e-book library. Suwon, Gyeonggi; 2017. https://news.suwon.go.kr/ebook/home/index.php. Accessed 1 Nov 2023. (in Korean).

Storeide MSB, George S, Sole A, Hardeberg JY. Standardization of digitized heritage: a review of implementations of 3D in cultural heritage. Herit Sci. 2023;11:249.

Zeiler X, Mukherjee S. Video game development in India: a cultural and creative industry embracing regional cultural heritage(s). Games Cult. 2022;17:509–27.

Suwon City. Hwaseong Haenggung Site - Basic and Surface Survey Report; 1994. (in Korean).

Gyeonggi Cultural Foundation Gyeonggi Historical and Cultural Heritage Center. Excavation report on the cultural relics of Hwaseong. Haenggung Square. Haenggung Square, Korea; 2008. https://memory.library.kr/dext/file/view/resource/111735 (in Korean).

Suwon City. 2000–2013 Suwon Hwaseong Castle Restoration Work. Korea, Suwon City. 2013. https://memory.library.kr/dext/file/view/resource/114089. (in Korean).

Suwon Hwaseong Fortress Agency’s Cultural Asset Facility Division. 2000–2013 Suwon Hwaseong Castle Restoration Work. National Archives of Korea. 2013. (in Korean).

Gyeonggi Cultural Foundation: Hwaseongseonggwae Architectural Glossary. 2007. https://memory.library.kr/items/show/210039623#. Accessed 15 Jan 2024. (in Korean).

Lee S, Yoo C, Im J, Cho D, Lee Y, Bae D. A hybrid machine learning approach to investigate the changing urban thermal environment by dynamic land cover transformation: a case study of Suwon, Republic of Korea. Int J Appl Earth Obs Geoinf. 2023;122:103408.

Suwon Hwaseong Fortress Agency’s Cultural Asset Facility Division. 2020 Suwon Hwaseong Fortress Wall Precision Survey Report. National Archives of Korea. 2020. (in Korean).

Böhm J, Haala N, Becker S. Façade modeling for historical architecture. In: XXI International CIPA Symposium; 2007. p. 1–6.

Ahn K-J, Choi JH. A study on the process to demolish official buildings in Suwon during Japanese colonial period. Archit Hist. 2020;29:19–28 (in Korean).

Cha JH, Kim YJ. Reassessing the proportional system of Joseon Era Wooden architecture: the bracket arm, length, and width as a standard modular method. MDPI Build. 2023;13(8):2069.

Diara F, Rinaudo F. IFC classification for FOSS HBIM: open issues and a schema proposal for cultural heritage assets. Appl Sci. 2020;10:8320. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10238320.

Brumana R, Ioannides M, Previtali M. Holistic heritage building information modeling (HHBIM): from nodes to hub networking, vocabularies and repositories. In: Proceedings of the ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Milan, 8–10 May 2019. 2019; p. 42.

Antonopoulou S, Bryan P. BIM for heritage: developing a historic building information model. Swindon: Historic England; 2017.

Barontini A, Alarcon C, Sousa HS, Oliveira DV, Masciotta MG, Azenha M. Development and demonstration of an HBIM framework for the preventive conservation of cultural heritage. Int J Archit Herit. 2022;16:1451–73.

Chen Y, Shooraj E, Rajabifard A, Sabri S. From IFC to 3D tiles: an integrated open-source solution for visualising BIMs on cesium. ISPRS Int J Geo Inf. 2018;7(10):393. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi7100393.

Francesca G, Francesca G, Massimiliano M, Anna DF. A HBIM pipeline for the conservation of large-scale architectural heritage: the city walls of Pisa. Herit Sci. 2024;12:1.

Cha J, Kim Y. Recognizing the correlation of architectural drawing methods between ancient mathematical books and octagonal timber-framed monuments in East Asia. Int J Archit Herit. 2023;17(6):988–1015.

Calì A, de Moraes PD, Valle ÂD. Understanding the structural behavior of historical buildings through its constructive phase evolution using H-BIM workflow. J Civ Eng Manag. 2020;26(5):421–34.

Acierno M, Cursi S, Simeone D, Fiorani D. Architectural heritage knowledge modeling: an ontology-based framework for conservation process constructive phase evolution using H-BIM workflow. J Cult Herit. 2017;24:124–33.

Simeone D, Cursi S, Carrara G. BIM and knowledge management for building heritage. In: Acadia 2014 Design Agency: Proceedings of the 34th Annual Conference of the Association for Computer Aided Design in Architecture. Roundhouse Publishing Group; 2014. p. 681–90.

OPEN and co-created metaVERSe for Europe. CORDIS EU research results. 2024. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/101135701. Accessed 23 Apr 2024.

King L, Stark J, Cooke P. Experiencing the digital world: the cultural value of digital engagement with Heritage. Herit Soc. 2016;9(1):76–101.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Suwon Hwaseong Fortress Agency’s Cultural Asset Facility Division for providing the research data.

Funding

This research was supported by the 2023 Cultural Heritage Smart Preservation & Utilization R&D Program, issued by the Cultural Heritage Administration, National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage (Project Name: A smart H-BIM modeling technology of wooden architecture for the conservation of Historical and Cultural Environment, Project Number: 2023A02P01-001, Contribution Rate: 100%).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SHK—concept, program creation, file conversion, content design, experimental design, review and editing. JHL—concept, original draft, text, investigation, resources, experimental design, review and editing. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript and participated in the review and editing processes.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, S., Lee, J. A study on the digital restoration of an ancient city based on historic building information modeling of wooden architectural heritage: focusing on Suwon Hwaseong. Herit Sci 12, 365 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01473-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01473-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

HBIM for the protection and management: a case study of Chinese timber architectural heritage

npj Heritage Science (2025)

-

Development and application of an HBIM method for timber structures integrated with digital technologies

npj Heritage Science (2025)