Abstract

Weiyang Palace, the royal palace of the Western Han Dynasty, is a part of the Silk Roads: the Routes Network of Chang’an-Tianshan Corridor on the World Heritage list. The south palace wall of Weiyang Palace is a well-preserved earthen heritage site within the palace, but it is undergoing continuous deterioration due to the influence of vegetation and external environmental factors. This study pioneers the integration of high-resolution three-dimensional LiDAR scanning with multi-source data analysis, including unprecedented on-site botanical surveys, to explore the subtle effects of different vegetation types on the structural integrity of the south palace wall. Through contour line analysis and facade grid analysis, we extracted the deterioration locations of typical sections of the earthen heritage sites. And we classified the overlying vegetation types on the wall using an object-oriented classification algorithm. Our findings reveal a complex interaction between vegetation and earthen structures: paper mulberry exhibits protective qualities against erosion, while Ziziphus jujuba significantly exacerbates structural vulnerabilities. The methodologies applied in this study for extracting deterioration at earthen heritage sites and integrating multi-source spatial data can serve as a technical application model for monitoring and analyzing the driving forces of earthen heritage sites along the entire Silk Road network, thereby better guiding the conservation of earthen heritage sites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cultural heritage is a crucial asset for humanity, encapsulating historical significance and significantly contributing to the sustainable development by substantially contributing to the socio-economic enhancement of local communities [1,2,3]. However, due to climatic conditions and human activities, both cultural heritage and its surrounding environment are increasingly facing deterioration [4, 5]. To address this, the United Nations has proposed the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which specifically mentions the need to further protect and safeguard cultural heritage in SDG 11.4 [6, 7]. Cultural heritage includes various categories such as ancient ruins, stone carvings, and cultural landscapes. Each type of cultural heritage has its unique characteristics, presenting technical challenges in the preservation of various kinds of heritage [4]. Consequently, there is a need for universally applicable technical methods tailored to specific types of heritage, which can serve as benchmarks for heritage management practices [8, 9].

Earthen heritage constitutes a significant category in the World Heritage list, accounting for 10% of the total entries [10]. During the Central Plains Dynasties in China, rammed earth technology was widely used in large constructions like the Great Wall [11]. Most earthen heritage sites, having been exposed to natural environmental factors such as wind, rain, and temperature variations over long periods, are progressively deteriorating [5]. Numerous studies have attempted to reveal the impacts of wind erosion and rain wash on these sites and to identify effective protective measures [12, 13]. However, constrained by technological limitations, previous studies primarily focused on small-scale assessments of deterioration, primarily employing manual methods, which often lacked follow-up surveys and were labor-intensive [14,15,16]. The advancement of spatial technology and remote sensing in recent years has enabled automatic and repetitive monitoring and protection of cultural heritage [17,18,19,20,21]. Among these technologies, LiDAR stands out as it can non-contact acquire information about earthen heritage sites using lasers, and its penetrative ability minimizes environmental interference during operation [22, 23]. Freeland et al. [24] combined LiDAR and automated feature extraction techniques to extract the earthworks in the Kingdom of Tonga; Wang et al. [25] extract ancient city wall by deep learning from LiDAR data. Despite these advancements, the primary application of LiDAR has been in recording and identifying earthen heritage sites, with less emphasis on detecting and analyzing deterioration.

In addition, previous research scenarios on earthen heritage sites have also been inadequate. Most earthen heritage sites are located in arid or semi-arid areas, where they are directly exposed to environmental factors, with research focusing on the impacts of wind and rain [5, 10, 26,27,28,29]. However, some earthen heritage sites are located in semi-humid and semi-dry regions, such as Xi'an, the eastern starting point of the Silk Road [30]. In these areas, there are earthen heritage sites where vegetation can grow. While it is generally accepted that vegetation mitigates the effects of environmental factors, the direct impact of the vegetation itself has been insufficiently explored [31, 32]. Moreno et al. [33] suggest that the impact of vegetation on earthen heritage sites varies with the type of vegetation, being either positive or negative.

Based on these research gaps, this study employs the south palace wall of Weiyang Palace as a case study, proposing a spatial analysis method that integrates the locations of wall deterioration with the types of overlying vegetation to assess the impact of vegetation on rammed earth walls. This method utilizes LiDAR data to evaluate wall collapses and on-site data collection to document wall cracks, alongside optical image data for vegetation classification. By correlating deterioration locations with vegetation distribution, this research elucidates the varying impacts of different vegetation types on the southern palace wall, informing future preservation strategies.

Materials and data

The south palace wall of Weiyang Palace

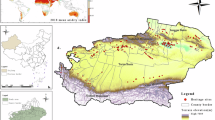

Weiyang Palace, once the royal palace of the Western Han Dynasty, is situated in Xi'an, Shaanxi Province, China, with geographic coordinates at 34°18′16″N and 108°51′26″E, covering a total area of 6.1 square kilometers (Fig. 1). Recognized as the eastern starting point of the Silk Road, it was designated a part of the Silk Roads: the Routes Network of Chang’an-Tianshan Corridor on the World Heritage list in 2014. The layout of the Weiyang Palace is characterized by palace walls, city walls, and archaeological remains of buildings. To date, archaeologists have identified 10 palace wall sites, with the south palace wall, particularly its western section, being relatively well-preserved.

The south palace wall of Weiyang Palace, constructed using the rammed earth technique, measures about 3 m in height and 8 m in width. It is exposed to various environmental factors such as humidity, temperature fluctuations, salinization, wind erosion, and rain wash, compounded by human activities. These factors lead to widespread deterioration, including cracking, powdering, erosion, and collapses. Vegetation on the wall also plays a significant role, with the canopy offering some protection against wind and rain, while the roots can destabilize the structure. Consequently, extracting the wall deterioration and understanding the interaction between vegetation and the wall are critically important for the conservation of the south palace wall. After conducting field surveys, we discovered that the south palace wall of Weiyang Palace hosts various types of vegetation, including paper mulberry, Ziziphus jujuba, Bromus, Paulownia tomentosa, Ailanthus altissima, and Robinia pseudoacacia. Paper mulberry and Ziziphus jujuba are the predominant species, whereas the others occur in significantly smaller quantities. Herbaceous plants such as Bromus are primarily found on the flat, upper sections of the walls and are nearly absent from the vertical facades, occurring in minimal amounts and having a negligible impact on the structural integrity compared to the more prevalent woody species. Therefore, this study primarily focuses on the impact of paper mulberry and Ziziphus jujuba on the deterioration of the wall. Additionally, the types of deterioration observed are numerous; this study categorizes them into small-scale deterioration, such as cracks, and large-scale deterioration, such as collapses.

Data description

We utilized the DJI M300 drone to design flight paths and captured a series of overlapping optical images, achieving a lateral overlap rate of 70% and a longitudinal overlap rate of 50%. These optical images were registered and stitched together using DJI TERRA software, producing an orthophoto of the southern palace wall with a resolution of 0.17 m (Fig. 2a). Additionally, the drone was equipped with a Livox LiDAR sensor to conduct low-altitude flights over the wall. By controlling the drone to direct laser pulses from both the top and the sides onto the wall, we obtained detailed information about the wall, especially its vertical facades (Fig. 2b).

The cracks in the wall are too small for current spatial technologies to effectively detect. Consequently, we gathered data on these cracks through field surveys, measuring their location, length, and width on the vertical facades on-site, and documenting the growth of root systems within them. We then digitized these records into spatial data, complete with location and attribute details. For large-scale deterioration, such as collapses, we utilized LiDAR point cloud to pinpoint the locations of the collapses and verified the accuracy using on-site recorded positions and photographs of the collapses.

Methods

This section introduces a combined analysis method employing optical image and LiDAR data to assess the impact of vegetation on ancient sites (Fig. 3). We initiated by digitizing the wall’s three-dimensional (3D) structure, followed by delineating the cracks at their corresponding locations on the wall model. Additionally, we employed the innovative application of contour line analysis and facade grid analysis to identify the collapse locations of the wall. For the optical image data captured by the drone, we conducted multi-scale segmentation to create image objects, and then calculated the internal texture features of each object. These texture features, along with the original image bands, were input into a random forest classifier to produce a map classifying the types of vegetation covering the south palace wall. Finally, by integrating the results from the extraction of deterioration locations and the classification of vegetation, we conducted an analysis of how different vegetation types on the wall influence its deterioration.

Wall deterioration detection

Firstly, we applied top-down ground filtering methods to the LiDAR point cloud data to remove the vegetation point cloud, retaining only the ground point data. In this process, we employed a cloth simulation filter to separate the vegetation point cloud from the point cloud of the wall itself. The cloth simulation filter works by simulating the physical process of cloth draping over an object to separate ground and non-ground points [34]. The procedure begins by inverting the point cloud, then analyzing the interaction between the cloth nodes and the corresponding LiDAR points to define the final cloth shape, which represents the ground points. Once the ground points were obtained, we created a multipatch feature in ArcGIS software based on this ground point data, resulting in a spatially referenced 3D model. We then transferred the field-recorded locations, lengths, and trends of wall cracks onto this model, completing the spatial digitization of the wall cracks.

To identify collapse locations digitally on the wall, we generated contour lines on the 3D model, segmented at approximately 2-m intervals horizontally into curved segments. We calculated the curvature of these segments and categorized them by different colors based on their curvature, which was determined by dividing the length of each contour segment by the straight-line distance between its endpoints. In the color-graded map of contour line curvature, areas of the wall collapse were identified as regions where high-curvature contour lines clustered and concaved towards the inside of the wall. Following this principle, we recorded the identified collapse locations on the wall.

In the initial top-down ground point filtering process, we treated the ground point cloud data as representing the wall itself, and used contour line analysis to extract collapses observed in the vertical direction. However, collapses such as partial indentations of the wall facade were not observable from a vertical perspective. To address this issue, Cai et al. [35] proposed a method involving the horizontal placement of the facade, followed by the use of existing ground filtering algorithms to separate the wall surface and protrusions. In this study, we manually separated the point cloud data containing the wall facade from original point cloud data, rotated it 90 degrees to horizontally place the facade, and then applied the cloth simulation filter to obtain the point cloud data of the wall facade. From this facade point cloud data, we identified areas of indentation, pinpointing collapse locations on the wall from a horizontal perspective.

Vegetation classification

We employed an object-oriented approach for vegetation classification, a rapidly emerging technique in Geographic Information System (GIS) and archaeology, which provides a more accurate representation of geographical objects compared to single pixels [36, 37]. Initially, the drone’s optical images underwent multi-scale segmentation using eCognition software. The results of this segmentation were influenced by the scale of segmentation, shape, and compactness parameters. Based on preliminary research and subsequent experiments, we set the segmentation scale to 50, the shape parameter to 0.5, and the compactness to 0.8 [38].

After acquiring image objects, using only the original red, green, and blue bands of the drone's image as classification features was insufficient. Therefore, we calculated the internal texture features of these objects as supplementary features to improve the classification results. We generated a gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) for the pixels within these image objects, a method that tabulates the frequency of pixel gray level combinations [39]. Statistical measures derived from the GLCM, such as mean, dissimilarity, second-order moment, contrast, correlation, variance, homogeneity, and entropy, were used to effectively enhance image classification [40].

Finally, we developed a random forest classification model incorporating these features to ascertain vegetation types. The random forest model achieves robust classification by combining multiple weak classifiers. These weak classifiers were built using decision tree algorithms, with the Gini index serving as the criterion for constructing the decision tree nodes [41]. The Gini index is calculated as follows:

where \(Gini\) is the Gini index, \(I\) represents the number of classes, \(i\) denotes the class index, and \({p}_{i}\) is the probability of occurrence of class \(i\). A smaller Gini index indicates a higher purity of the sample set. Therefore, in constructing each tree node within the random forest classifier, the feature that results in the largest decrease in the Gini index is chosen for splitting, continuing until a leaf node is reached.

To evaluate the accuracy in vegetation classification, Precision, Recall, and F1 score were served as metrics. They are formulated ad follows:

Where \(TruePositive\) represents the quantity of positive samples correctly classified as such, \(FalsePositive\) represents the quantity of negative samples incorrectly classified as positive, and \(FalseNegative\) represents the quantity of positive samples incorrectly classified as negative.

Analysis of the impact effects of vegetation on wall deterioration

We analyze the overlapping digital data of vegetation types, cracks, and collapses on the wall to establish their spatial interrelationships This analysis involves conducting spatial statistical evaluations to digitally represent and quantitatively assess how vegetation growth and its types are spatially correlated with the deterioration patterns of the wall. This method enables us to understand how different types of vegetation correlate with and potentially contribute to collapses of the wall. Additionally, based on field survey data, which includes measurements of the lengths and widths of cracks as well as the conditions of root system growth within them, we further identified the impact of vegetation on wall cracks through statistical analysis.

Results

Extraction of wall deterioration

The south palace wall of Weiyang Palace is divided into eastern and western sections, separated by a road. The eastern section, as depicted in the model (Fig. 4a), lacks the original and regular shape of the wall, indicating significant damage verified during field inspection (Fig. 4b). Additionally, the presence of large trees in this area impeded the penetration of the LiDAR signal. In contrast, the 3D model of the western section more clearly depicts the wall’s overall structure (Fig. 4c). Consequently, our subsequent research and analysis focused on the western section. We established the starting point of the western section of the wall as the origin, with westward direction serving as the positive direction for positioning wall deterioration. Based on the cracks recorded during field surveys, we marked these cracks on the corresponding locations of the wall model.

During our comprehensive field surveys, combined with an analysis of orthophoto and LiDAR point cloud data, we identified significant structural collapses along the western section of the wall, specifically between 130 and 740 m. Here, the earth from collapsed sections had formed sloped terrains. Vegetation on these slopes, predominantly large paper mulberry trees, grew more rapidly than on the vertical rammed earth surfaces, thereby obscuring large sections of the wall. The dense foliage of these trees not only posed challenges for field sampling but also severely obstructed the LiDAR signals, complicating our data collection efforts. Due to these obstructions, we decided to exclude the segment from 130 to 740 m from the collapse extraction process in our study. To facilitate a clearer presentation and analysis, the remaining sections of the wall were subdivided into three distinct parts: Part 1 extends from 50 to 130 m; Part 2 ranges from 750 to 1050 m; and Part 3 spans from 1200 to 1300 m.

On the facade of the western section of the wall, we generated contour lines at 0.2-m elevation intervals and segmented these lines at a horizontal distance of 2 m, subsequently calculating the curvature of these segments and applying color grading based on their curvature. In the color-graded curvature map of the contour lines, the areas of wall collapse are indicated by the clustering of high-curvature contour lines that concave inward towards the wall. Based on this criterion, we identified the areas of collapse on the wall. Additionally, the protruding paper mulberry trees caused the contour lines to bulge outward before concaving inward. This required a manual comparison with the LiDAR point cloud data to exclude any misidentified collapse areas. Ultimately, using the contour line method, we identified a total of 29 collapse locations., as illustrated in Fig. 5.

Based on the 3D model, we manually extracted the point cloud data of the wall's facade and rotated it by 90 degrees before reapplying the cloth simulation filter. Using the filtered point cloud data, we constructed a grid model and visually interpreted areas of local indentation, identifying them as horizontal collapse locations on the wall. In total, we identified an additional 10 collapse locations (Fig. 6).

Through the analysis of contour lines and the facade grid, we identified a total of 39 collapse locations on the wall. We physically photographed and recorded 20 instances of wall collapse on-site. Upon detailed comparison with the digitally identified collapse locations, 18 out of the 20 recorded instances matched those detected by digital methods (Fig. 7). The detection accuracy for the collapse of Weiyang Palace’s south palace wall was determined to be 90%. This close alignment between the collapse locations identified through digital methods and those observed during field surveys demonstrates the validity of our collapse data extraction technique, confirming that our method accurately reflects the actual conditions of deterioration.

Vegetation classification

To streamline our study, we focused our classification on Ziziphus jujuba, paper mulberry, and an ‘others’ category, which includes bare earth and less common vegetation such as Bromus. After performing multi-scale segmentation, we obtained 179,202 image objects, delineating 1075 patches as paper mulberry samples, 336 as Ziziphus jujuba samples, and 186 as samples of the ‘others’ category. We divided the sample set into a training set and a test set in 7:3 ratio and evaluated the classification model on the test set. We used Precision, Recall and F1-score as metrics (Table 1). The final results of the vegetation types covering the wall are as presented in Fig. 8. The final classification ratios for paper mulberry, Ziziphus jujuba, and 'other' were 0.78, 0.07, and 0.14, respectively. Paper mulberry and Ziziphus jujuba are in a competitive state on the wall, with paper mulberry occupying a dominant position.

Analysis of the impact effects of vegetation on wall deterioration

Combining the collapse locations extracted in Sect. “Extraction of wall deterioration” with the vegetation classification results from Sect. “Vegetation classification” for an overlay analysis, we calculated the proportions of overlying surface types within a 0.5 m buffer zone around the identified collapse locations. We found that within the buffer zones of these collapses, 74.6% of the area is covered by Paper mulberry, 16.3% by Ziziphus jujuba, and 9.1% has no vegetation coverage. Notably, vegetation was present in the 0.5 m buffer zone around every collapse location, which indicates that overlying vegetation is correlated with wall collapses. Furthermore, comparing this with the overall proportions of vegetation types on the wall facade (paper mulberry: Ziziphus jujuba: others = 0.78: 0.07: 0.14), it appears that locations with Ziziphus jujuba are more prone to collapses.

We conducted an overlay analysis of the wall cracks’ attributes in conjunction with the types of vegetation covering the wall. Figure 9 displays the locations, lengths, and widths of the cracks on the wall and the types of vegetation above them. It is evident that the cracks without vegetation above them are significantly larger in both length and width than those with vegetation, and these cracks are primarily concentrated in the 750 to 800 m area. Based on our field investigations, we discovered that this particular section had undergone artificial treatment, resulting in the absence of vegetation growth above it. Consequently, due to the erosion caused by rainwater, this area experienced a significant number of large cracks. In the other cases, cracks under paper mulberry averaged 0.95 m in length and 3.37 cm in width, while those under Ziziphus jujuba averaged 1.17 m in length and 1.41 cm in width, indicating that cracks under paper mulberry tend to be wider, whereas those under Ziziphus jujuba are longer. Additionally, we noticed that 32% of the cracks had Ziziphus jujuba growing above them, a proportion much higher than its occurrence on the wall (7%), suggesting a higher likelihood of crack formation in areas with Ziziphus jujuba.

During field investigations, we discovered that 62% of the cracks had vegetation roots growing directly within them; of these, 37% were from paper mulberry and 63% from Ziziphus jujuba. This distribution suggests that Ziziphus jujuba plays a significant role in the formation of wall cracks. The ratio of paper mulberry to Ziziphus jujuba in the classified overlying vegetation types on the wall is 0.78 to 0.07, highlighting the disproportionate prevalence of Ziziphus jujuba roots within the cracks. This suggests a strong tendency for Ziziphus jujuba roots to infiltrate and negatively affect the wall structure. Further statistical analysis shows that both paper mulberry and Ziziphus jujuba roots increase the average length and width of the cracks compared to conditions without roots. Specifically, paper mulberry roots significantly enhance the width, while Ziziphus jujuba roots notably increase the length (Table 2).

We conducted field observations and analyzed the characteristics of Ziziphus jujuba and paper mulberry roots (Fig. 10). We found that paper mulberry roots are thick but shallow, while Ziziphus jujuba roots are slender but penetrate deeper into the soil. Additionally, paper mulberry typically has a single main root, whereas Ziziphus jujuba roots often have multiple branches. The characteristics of Ziziphus jujuba roots make them more likely to infiltrate the wall structures, which is why the majority of roots found in cracks are from Ziziphus jujuba, and these cracks are typically narrower and longer. In contrast, paper mulberry’s thicker roots, with fewer splits, result in fewer but significantly wider cracks.

The analysis indicates that deterioration on the wall is associated with the vegetation growing on them: In terms of collapses, the presence of vegetation tends to increase the likelihood of collapses, with Ziziphus jujuba having a greater impact; regarding cracks, paper mulberry is associated with wider cracks, while Ziziphus jujuba is associated with longer cracks. Areas with Ziziphus jujuba are particularly prone to forming cracks. Importantly, although paper mulberry has a detrimental effect on the severity of cracks, it still provides better protection than leaving the wall exposed to external environmental conditions.

Discussion

Advancement and limitation

Spatial technology is increasingly being applied in the field of cultural heritage [20, 42]. However, its use is often limited to digitalizing and demonstrating archaeological sites [43], with only a minority of studies employing intelligent algorithms to extract useful information for heritage monitoring and protection from spatial data [44, 45]. The deterioration of earthen heritage sites results from a combination of multiple factors [46]. Therefore, it is essential not only to use spatial technology for monitoring these sites but also to explore the underlying forces driving their deterioration to develop effective protection strategies. Regrettably, research in these areas tends to be conducted in isolation: studies utilizing spatial technology typically concentrate on data acquisition and site monitoring, whereas those analyzing deterioration mechanisms focus primarily on these processes [47], frequently relying on small-scale laboratory experiments that fail to offer a comprehensive understanding of the sites or viable conservation solutions.

This study integrated multi-source spatial data to monitor and analyze the deterioration and driving forces of the Han Dynasty Weiyang Palace's south palace wall. Using the cloth simulation filter, especially after the 90-degree rotation, we developed three-dimensional data of the wall itself and portrayed its deterioration through a series of spatial analysis methods. These methods are crucial for data processing and information extraction applicable to earthen heritage sites like the wall. By combining intelligent algorithms with high-resolution drone image, we classified the overlying vegetation on the wall. Through overlay and statistical analysis, we analyzed the impact of the vegetation on the wall. The approach of integrating multi-source data for overlay analysis in this study can be extended to similar research on earthen heritage sites. Beyond the impact of vegetation, sensors mounted on drones can infer temperature, humidity and so on [48, 49], which can be overlaid with the extracted locations of wall deterioration for further analysis, identifying driving forces and formulating scientific conservation recommendations. Furthermore, this study highlights the advantages of spatial technology for the monitoring and preventive conservation of cultural heritage sites. By offering detailed and accurate assessments of site conditions, spatial technology facilitates timely interventions that can prevent further deterioration. This proactive approach in conservation strategy is crucial for preserving the integrity and value of heritage sites worldwide.

Our research has developed a method for analyzing the driving forces affecting earthen heritage sites using spatial technology, but it has some limitations. With the advancement of deep learning algorithms [50], it has become possible to automatically extract wall deterioration from LiDAR point cloud data or 3D models. However, at this stage, our study only includes the case of Weiyang Palace's south palace wall, which is insufficient to build an adequate sample set for deep learning. In reality, the Silk Road is home to a multitude of earthen heritage sites. Incorporating these sites into comprehensive research could significantly enhance the potential for automated and accurate identification of site deterioration. Moreover, during our research process, we found that the scale of the cracks in the wall is too small for detection by the data from airborne platforms, so our data on cracks was manually recorded. In winter, when vegetation leaves wither, close-range photogrammetric techniques can be used to identify cracks [51]. The identified cracks can be digitally mapped onto the surface of the wall, allowing for direct calculation of their lengths and widths. This is also a direction for our future research.

Furthermore, through spatial technology, we have unearthed a series of evidential chains that reveal the impact of vegetation on the deterioration of the walls. However, beyond the clearly observable expansion of cracks caused by root systems, the specific mechanisms of vegetation’s impact on the walls remain unclear. Nevertheless, our use of multi-source data analysis and structures provides a clear direction for subsequent biochemical research. Future studies might require a more detailed approach, one that combines biochemical analyses with spatial data to comprehensively understand these interactions.

Suggestions for the protection of the south palace wall

The deterioration of earthen heritage sites in natural environments is complex, making it challenging to completely prevent deterioration [52]. Our experimental data indicate that the south palace wall of Weiyang Palace is currently undergoing gradual deterioration. Consequently, it is imperative to use suitable materials to reinforce the wall's structure to mitigate further extensive damage [53]. Ziziphus jujuba significantly contributes to the formation of cracks and collapses in the wall, while paper mulberry, although slightly exacerbating the cracks, offers better protection than exposing the wall directly to external environmental conditions (Fig. 11). On the wall, paper mulberry and Ziziphus jujuba are in competition, with paper mulberry in a dominant position. Given these dynamics, we recommend employing chemical methods to eradicate Ziziphus jujuba to prevent further deterioration. Until an appropriate man-made shelter is created for the wall, the paper mulberry trees on it should be preserved to avoid direct erosion by wind and rain.

Conclusion

This study has offered comprehensive insights into the deterioration of the south palace wall of Weiyang Palace. By integrating multi-source spatial data, including LiDAR and high-resolution drone image, we have successfully identified the deterioration along the wall and analyzed the impact effects of vegetation on wall deterioration. Utilizing innovative methods such as contour line analysis and facade grid analysis, we effectively pinpointed the locations of deterioration along the wall. These techniques enabled a detailed spatial representation of the wall's condition, demonstrating the value of advanced spatial analysis in cultural heritage preservation. And our research employed an object-oriented approach, integrating texture features to classify the types of overlying vegetation on the wall. This classification played a crucial role in understanding the interaction between vegetation and the wall’s deterioration. Finally, we discovered that paper mulberry and Ziziphus jujuba compete for dominance on the wall and their impact on the wall's structure is distinct. Paper mulberry, despite slightly exacerbating the cracks, offers a level of protection against direct environmental exposure, whereas Ziziphus jujuba contributes significantly to the formation of cracks and collapses.

The study highlights the complexity of conserving earthen heritage sites, especially those continuously exposed to natural elements and human interventions. It is clear that a one-size-fits-all approach is not feasible for the preservation of such earthen heritage sites. Our research provides a case study on the detailed analysis of the driving forces behind wall deterioration using spatial technology and intelligent algorithms. This approach can guide more precise conservation strategies for earthen heritage sites.

In conclusion, our study not only advances the understanding of biotic factors affecting earthen heritage deterioration but also sets a precedent for the application of integrated spatial and botanical analysis in the conservation of cultural heritage worldwide. Furthermore, the utilization of spatial technology in this study showcases its potential for monitoring and preventive conservation of cultural heritage sites, highlighting its vital role in enhancing heritage management and protection strategies.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Bowitz E, Ibenholt K. Economic impacts of cultural heritage—research and perspectives. J Cult Herit. 2009;10(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2008.09.002.

Gravagnuolo A, Micheletti S, Bosone M. A participatory approach for “circular” adaptive reuse of cultural heritage, building a heritage community in Salerno, Italy. Sustainability. 2021;13(9):4812. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094812.

Cheng W, Fulong C, Wei Z, Huafen Y. Sequential PSInSAR approach for the deformation monitoring of the Nanjing Ming Dynasty City Wall. Natl Remote Sens Bull. 2022;25(12):2381–95. https://doi.org/10.11834/jrs.20211098.

Wang X, Li H, Wang Y, Zhao X. Assessing climate risk related to precipitation on cultural heritage at the provincial level in China. Sci Total Environ. 2022;835: 155489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155489.

Shao M, Li L, Wang S, Wang E, Li Z. Deterioration mechanisms of building materials of Jiaohe ruins in China. J Cult Heritage. 2013;14(1):38–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2012.03.006.

Petti L, Trillo C, Makore BN. Cultural heritage and sustainable development targets: a possible harmonisation? Insights from the European perspective. Sustainability. 2020;12(3):926. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030926.

Guo H, Chen F, Tang Y, Ding Y, Chen M, Zhou W, et al. Progress toward the sustainable development of world cultural heritage sites facing land-cover changes. Innovation. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xinn.2023.100496.

Richards J, Wang Y, Orr S, Viles H. Finding common ground between United kingdom based and Chinese approaches to earthen heritage conservation. Sustainability. 2018;10(9):3086. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093086.

Gutiérrez-Carrillo ML, Arizzi A. How to deal with the conservation of the archaeological remains of earthen defensive architecture: the case of Southeast Spain. Archaeol Anthropol Sci. 2021;13(8):131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-021-01358-5.

Richards J, Zhao G, Zhang H, Viles H. A controlled field experiment to investigate the deterioration of earthen heritage by wind and rain. Herit Sci. 2019;7(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-019-0293-7.

Xie L, Wang D, Zhao H, Gao J, Gallo T. Architectural energetics for rammed-earth compaction in the context of Neolithic to early Bronze age urban sites in Middle Yellow River Valley, China. J Archaeol Sci. 2021;126: 105303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2020.105303.

Rainer L. Deterioration and pathology of earthen architecture. Terra Lit Rev. 2008;45:58.

Fodde E, Khan MS. Affordable monsoon rain mitigation measures in the world heritage site of Moenjodaro, Pakistan. Int J Archit Herit. 2013;11(2):161–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15583058.2013.771293.

Parisi F, Asprone D, Fenu L, Prota A. Experimental characterization of Italian composite adobe bricks reinforced with straw fibers. Compos Struct. 2015;122:300–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2014.11.060.

Du Y, Chen W, Cui K, Zhang K. Study on damage assessment of earthen sites of the Ming Great Wall in Qinghai province based on Fuzzy-AHP and AHP-TOPSIS. Int J Archit Herit. 2019;14(6):903–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/15583058.2019.1576241.

Zhang Y, Ye WM, Chen B, Chen YG, Ye B. Desiccation of NaCl-contaminated soil of earthen heritages in the Site of Yar City, northwest China. Appl Clay Sci. 2016;124–125:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2016.01.047.

Chen F, Lasaponara R, Masini N. An overview of satellite synthetic aperture radar remote sensing in archaeology: From site detection to monitoring. J Cult Herit. 2017;23:5–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2015.05.003.

Luo L, Wang X, Guo H, Lasaponara R, Zong X, Masini N, et al. Airborne and spaceborne remote sensing for archaeological and cultural heritage applications: a review of the century (1907–2017). Remote Sens Environ. 2019;232: 111280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2019.111280.

Remondino F. Heritage recording and 3D modeling with photogrammetry and 3D scanning. Remote Sens. 2011;3(6):1104–38. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs3061104.

Campiani A, Lingle A, Lercari N. Spatial analysis and heritage conservation: leveraging 3-D data and GIS for monitoring earthen architecture. J Cult Herit. 2019;39:166–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2019.02.011.

Chen F, Guo H, Ma P, Tang Y, Wu F, Zhu M, et al. Sustainable development of World cultural heritage sites in China estimated from optical and SAR remotely sensed data. Remote Sens Environ. 2023;298: 113838. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2023.113838.

Mallet C, Bretar F. Full-waveform topographic lidar: state-of-the-art. ISPRS J Photogramm Remote Sens. 2009;64(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2008.09.007.

Comer DC, Comer JA, Dumitru IA, Ayres WS, Levin MJ, Seikel KA, et al. Airborne LiDAR reveals a vast archaeological landscape at the Nan Madol world heritage site. Remote Sens. 2019;11(18):2152. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11182152.

Freeland T, Heung B, Burley DV, Clark G, Knudby A. Automated feature extraction for prospection and analysis of monumental earthworks from aerial LiDAR in the Kingdom of Tonga. J Archaeol Sci. 2016;69:64–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2016.04.011.

Wang S, Hu Q, Wang S, Ai M, Zhao P. Archaeological site segmentation of ancient city walls based on deep learning and LiDAR remote sensing. J Cult Herit. 2024;66:117–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2023.11.005.

Guo Q, Wang Y, Chen W, Pei Q, Sun M, Yang S, et al. Key issues and research progress on the deterioration processes and protection technology of earthen sites under multi-field coupling. Coatings. 2022;12(11):1677. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings12111677.

Du Y, Chen W, Cui K, Gong S, Pu T, Fu X. A model characterizing deterioration at earthen sites of the Ming Great Wall in Qinghai province. China Soil Mech Found Eng. 2017;53(6):426–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11204-017-9423-y.

Richards J, Mayaud J, Zhan H, Wu F, Bailey R, Viles H. Modelling the risk of deterioration at earthen heritage sites in drylands. Earth Surf Process Landf. 2020;45(11):2401–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.4887.

Canuti P, Casagli N, Catani F, Fanti R. Hydrogeological hazard and risk in archaeological sites: some case studies in Italy. J Cult Herit. 2000;1(2):117–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1296-2074(00)00158-8.

Liu S, Huang S, Xie Y, Wang H, Huang Q, Leng G, et al. Spatial-temporal changes in vegetation cover in a typical semi-humid and semi-arid region in China: changing patterns, causes and implications. Ecol Indic. 2019;98:462–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.11.037.

Richards J, Bailey R, Mayaud J, Viles H, Guo Q, Wang XJSR. Deterioration risk of dryland earthen heritage sites facing future climatic uncertainty. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):16419. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73456-8.

Wolfe SA, Nickling WG. The protective role of sparse vegetation in wind erosion. Prog Phys Geogr. 1993;17(1):50–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/030913339301700104.

Moreno M, Ortiz P, Ortiz R. Analysis of the impact of green urban areas in historic fortified cities using landsat historical series and normalized difference indices. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):8982. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-35844-8.

Zhang W, Qi J, Wan P, Wang H, Xie D, Wang X, et al. An easy-to-use airborne LiDAR data filtering method based on cloth simulation. Remote Sens. 2016;8(6):501. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs8060501.

Cai S, Zhang S, Zhang W, Fan H, Shao J, Yan G, et al. A general and effective method for wall and protrusion separation from facade point clouds. J Remote Sens. 2023;3:0069. https://doi.org/10.34133/remotesensing.0069.

Blaschke T, Hay GJ, Kelly M, Lang S, Hofmann P, Addink E, et al. Geographic object-based image analysis–towards a new paradigm. ISPRS J Photogramm Remote Sens. 2014;87:180–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2013.09.014.

Magnini L, Bettineschi C. Theory and practice for an object-based approach in archaeological remote sensing. J Archaeol Sci. 2019;107:10–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2019.04.005.

Chen G, He Y, De Santis A, Li G, Cobb R, Meentemeyer RK. Assessing the impact of emerging forest disease on wildfire using Landsat and KOMPSAT-2 data. Remote Sens Environ. 2017;195:218–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2017.04.005.

Haralick RM, Shanmugam K, Dinstein IH. Textural features for image classification. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern. 1973;6:610–21. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSMC.1973.4309314.

Gadkari D. Image quality analysis using GLCM. 2004.

Breiman L. Random forests. Mach Learn. 2001;45:5–32. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010933404324.

De Reu J, Plets G, Verhoeven G, De Smedt P, Bats M, Cherretté B, et al. Towards a three-dimensional cost-effective registration of the archaeological heritage. J Archaeol Sci. 2013;40(2):1108–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2012.08.040.

Landeschi G, Nilsson B, Dell’Unto N. Assessing the damage of an archaeological site: new contributions from the combination of image-based 3D modelling techniques and GIS. J Archaeol Sci: Rep. 2016;10:431–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2016.11.012.

Du Y, Chen W, Cui K, Zhang J, Chen Z, Zhang Q. Damage assessment of earthen sites of the Ming Great Wall in Qinghai Province: a comparison between support vector machine (SVM) and BP neural network. J Comput Cult Herit (JOCCH). 2020;13(2):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1145/3376120.

Lercari N. Monitoring earthen archaeological heritage using multi-temporal terrestrial laser scanning and surface change detection. J Cult Herit. 2019;39:152–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2019.04.005.

Richards J, Viles H, Guo Q. The importance of wind as a driver of earthen heritage deterioration in dryland environments. Geomorphology. 2020;369: 107363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2020.107363.

Richards J, Guo Q, Viles H, Wang Y, Zhang B, Zhang H. Moisture content and material density affects severity of frost damage in earthen heritage. Sci Total Environ. 2022;819: 153047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153047.

Frodella W, Elashvili M, Spizzichino D, Gigli G, Adikashvili L, Vacheishvili N, et al. Combining infrared thermography and uav digital photogrammetry for the protection and conservation of rupestrian cultural heritage sites in Georgia: a methodological application. Remote Sens. 2020;12(5):892. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12050892.

Su T-C. Environmental risk mapping of physical cultural heritage using an unmanned aerial remote sensing system: a case study of the Huang-Wei monument in Kinmen, Taiwan. J Cult Herit. 2019;39:140–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2019.03.011.

Guo Y, Wang H, Hu Q, Liu H, Liu L, Bennamoun M. Deep learning for 3d point clouds: a survey. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2020;43(12):4338–64. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2020.3005434.

Galantucci RA, Fatiguso F. Advanced damage detection techniques in historical buildings using digital photogrammetry and 3D surface anlysis. J Cult Herit. 2019;36:51–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2018.09.014.

Li L, Shao M, Wang S, Li Z. Preservation of earthen heritage sites on the Silk Road, northwest China from the impact of the environment. Environ Earth Sci. 2011;64:1625–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-010-0829-3.

Correia M, Guerrero L. Conservation of earthen building materials. Encycl Archaeol Sci. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119188230.saseas0117.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the Xi'an Academy of Conservation and Archaeology for their generous support and funding.

Funding

This work was jointly support by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (grant no. 42271327) and 'Silk Road: Digital Preservation of Cultural Heritage Sites in the Xi'an Section of the Chang'an-Tianshan Corridor Network' project of the Xi'an Academy of Conservation and Archaeology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, L.T. and F.C.; methodology, S.G., F.C. and L.T.; software, S.G., P.S and Z.X; formal analysis, S.G. and F.C.; investigation, S.G., W.L., Y.L, H.L and C.C.; resources, X.Y. and W.L.; data curation, S.G. and X.Z; writing—original draft preparation, S.G.; writing—review and editing, S.G. L,T and F.C.; visualization, S.G., W.Z., and M.Z.; supervision, F.C. and L.T.; project administration, F.C. and L.T.; funding acquisition, F.C. and L.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, S., Tao, L., Chen, F. et al. Extraction of deterioration and analysis of vegetation impact effects on the south palace wall of Weiyang Palace. Herit Sci 12, 364 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01485-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01485-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Comparative analysis of physical characteristics of traditional rammed earth dwellings in Macau

npj Heritage Science (2025)

-

Spontaneous vegetation on the Jiankou Great Wall Heritage Site as ecological blueprint for the soft capping

npj Heritage Science (2025)