Abstract

As an important military defense project in Chinese history, the Ming Dynasty Great Wall and its associated military settlements played a crucial role in maintaining border security. A systematic analysis of how military settlements allocated resources based on external threats and geo-strategic needs is essential to understanding their settlements defense systems. However, this aspect has been relatively under-explored in existing research. Therefore, a resource allocation assessment model for Great Wall military settlements during the Cold Weapon era is established to facilitate a more scientific analysis and quantitative assessment of Military Defense Capabilities(MDC) and Military Requirements(MR). This study employs a combined Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) approach to determine the weight of each indicator for both military defense capability and military requirement. Spatial clustering using K-means is conducted to visualize the distribution of these strengths and weaknesses. An Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression model links military requirements with defense capabilities, assessing the relationship between settlement locations and historical battle sites. Residual analysis is utilized to identify areas of resource over-allocation or under-allocation. The study reveals that the regional differences in military defense capabilities and requirements within the Zhenbao Town area during the Ming Dynasty correspond closely with the locations of frequent conflicts. This finding suggests that the distribution of defensive capabilities were strengthened in areas with challenging terrain, while the effectiveness and allocation of defense capabilities were determined by logistical support and transportation conditions. This study enhances our understanding of historical military strategies from a historical geography perspective and offers innovative insights for analyzing Great Wall settlement, moving beyond mere sensory intuition and historical experience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Ming Great Wall, an important component of the world cultural heritage, was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1987 [1]. It includes numerous military settlements and defensive structures, collectively forming the Great Wall’s defensive system [2]. The primary purpose of the Great Wall’s military defense line was protection [3], and the military settlements, responsible for combat operations, were key to its defensive capabilities. The effective allocation of military resources by the government depends on the accurate assessment of military requirements [4], which determined the capacity of these settlements to resist foreign invasions. However, during this period, military settlements faced challenges in resource allocation, including geographical constraints, limited strategic resources, and the complexities of material deployment [5]. Ancient governments had to consider how the defenses of military settlements were influenced by natural geography and the socio-human environment factors, and how to ensure national defense and security while strategically allocating resources to support economic development.

Ancient military settlements have attracted the interest of researchers across fields such as architecture, geography, and planning, recognizing that a deeper understanding of these settlements not only enriches their defense mechanisms but also contributes to the preservation and integration of such cultural heritage [6]. Despite this growing interest, there are currently no effective tools or methods to analyze the resource allocation assessment for ancient military settlements situated in complex terrains. Developing and implementing such tools is essential, particularly for the military defense zones of the Ming Great Wall, to provide insights beyond qualitative research and historical experience by applying military resourcing models to the Great Wall settlements.

In recent years, studies leveraging the GIS platforms have examined military resources in ancient settlements from various perspectives, such as ecological security [7], military security [8], transport accessibility [9], and troop deployment [10]. These factors collectively influence the defensibility of the settlements. Ecological considerations, including topography, water sources, and arable land, are deemed essential for the sustainable development of these settlements. Meanwhile, military considerations, such as the positioning of the Great Wall, the spacing between settlements, and defense strategies directly impact defense effectiveness [11]. Wang’s study compared the average military weights with the frequency of intrusions during the Jiajing period, confirming that effective troop deployment enhances the defense efficiency of the garrison system [10]. Wu reconstructed historical maps and extracts spatial data to build a hierarchical evaluation model that quantifies the accessibility of military settlements, with the results visualized through spatial mapping [9]. Another study by Wang analyzed the ancient defense systems through terrain and water features, suggesting the establishment of military buffer zones based on spatial analysis [12]. Additionally, deep learning has been explored to predict military settlement locations and identify potential sites [13]. However, methodologies such as hierarchical evaluation models, entropy methods, and Voronoi diagrams for spatial segmentation have been predominantly applied to coastal military settlements, yet following the limited application to those along the Great Wall. Although existing researches have explored the various aspects of military resources in defense, the comprehensive allocation of these resources and their specific impact on the defensive capabilities of military settlements remain under-explored.

As the computational power of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) has increased, its application in spatial analysis of military clusters has become a vital tool for uncovering the social and power dynamics underlying these formations [14, 15]. Traditional studies, predominantly conducted from the perspective of Ming rulers, have examined how economic, social, geographic, and political factors constrained the capacity of military settlements to withstand external threats within defined regions, a concept referred to as Military Defense Capability (MDC) [16]. However, there is a relative lack of research that analyzes the attack risks faced by these military regions from the perspective of northern tribes, as well as a deficiency in quantitative assessments of these risks. To supplement this research gap, this paper introduces the concept of Military Requirement (MR), defined as the likelihood of military settlements becoming targets of attack [17]. This aspect remains under-explored in military history research. The study endeavors to assess the effectiveness of resource allocation and the judiciousness of strategic deployment through an analysis of the data patterns pertaining to MDC and MR. This endeavor fosters an innovative comprehension of ancient defensive strategies, adopting a perspective that considers the dynamics of adversaries on both sides.

This study employed a combination of Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to determine the weights of indicators for military defense capabilities and requirements, followed by K-means spatial clustering to visualize the spatial distribution strengths of MDC and MR. An Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression model is utilized to analyze the overall patterns of MDC and MR factors, linking military requirements and defense capability indicators. GIS tools are applied to assess the relationship between settlement locations and historical conflicts, identifying areas resources over-allocation or under-allocation through residual analysis. These analyses provide a deep understanding of the logic and distribution patterns of defense forces along the Great Wall and its military settlements, thereby supporting the protection and utilization of the Great Wall and related cultural heritage. This methodology signifies a significant trend in Great Wall research, particularly by enhancing the spatial analysis of complex military systems through modern science and technology [18].

This paper presents the construction, calibration, and application of a military resource allocation assessment model based on the GIS platform, focusing on Zhenbao Town along the Ming Great Wall. The primary objective is to comprehensively understand and analyze military strategy and policy-making during the Cold Weapon era, while improving the scientific analysis and quantitative assessment of MDC and MR. To achieve this, a quantitative model has been developed to support resource allocation in military settlements within complex terrains. The model introduced here has several key features: (1) This study applies the OLS regression model to historical military data, introducing a novel approach to analysis of military resource supply and requirement during the Cold Weapon era. (2) The current level of technological development, combined with the availability and quality of historical data, makes it feasible to implement such models in other military settlements along the Great Wall. (3) The validation method, combining digital calculations with historical data, ensures the accuracy and reliability of the numerical results, offering a new perspective on analyzing the heritage beyond sensory intuition and historical experience. (4) This study represents an interdisciplinary fusion, integrating methods from history, geography, and planning, to address the challenge of specializing complexity of military systems from a comprehensive perspective.

Materials and methods

Study area

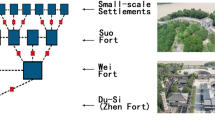

Given Zhenbao Town’s unique position as the “inner border” of the Great Wall and its distinctive mountainous terrain, this study focuses on the military settlements of Zhenbao Town during the Ming Dynasty. Constructed to defend the capital city, Zhenbao Town is situated within the Taihang Mountains, representing one of the most complex terrains within the Great Wall defense system. The Great Wall extended approximately 390 kms along the Zhenbao Town line, forming a north–south military defense line.The topography of the defense area generally slopes from west to east, characterized by diverse and intricate landscapes. The western region features mountains and hills interspersed with valleys, while the central and southeastern parts consist of plains. Military settlements strategically leveraged the unique geographical features of the Taihang Mountains, utilizing natural barriers as defensive fortifications and establishing passes at crucial intersections of land and water [19]. Located in Baoding, the town is divided into four main Roads from north to south: Mashuikou(MSK) Road, Zijingguan(ZJG) Road, Daomaguan(DMG) Road, and Longquanguan(LQG) Road, with commanders stationed at each pass.

This study references the Ming Dynasty maps from the “Historical Atlas of China [20]” to delineate the territory of Zhenbao Town during the Ming Dynasty. The jurisdiction of Zhenbao Town corresponds to parts of present-day Hebei Province, Beijing City and Shanxi Province, stretching from the Mentougou District in northern Beijing to Wu’an County in Handan City, in the south. Considering the strategic importance of the transportation routes through the Taihang Mountains, the northern region beyond the Jundu Pass is also included. To ensure a comprehensive analysis of the Great Wall, we account for its entire length and extend westward to encompass any adjacent areas. Due to the lack of precise historical records to define the specific defense zones of Zhenbao Town during the Ming Dynasty, and the absence of detailed administrative and military boundaries, the scope of this study is determined based on current administrative divisions. Through this approach, the surrounding areas of the Zhenbao Town Great Wall defense system can be roughly delineated. However, it is worth noting that, as shown in Fig. 1, this delineation serves primarily as a general framework for studying various factors related to the defense system, rather than representing the exact historical defense zones of Zhenbao Town.

Data sources

The supporting data for this study were obtained from the following sources as illustrated in (Fig. 2):

-

1.

Terrain Data (Fig. 2\(\textcircled {1}\)): This data was sourced from the Geospatial Data Cloud platform. It consists of DEM terrain data at a resolution of 30 m\(\times \)30 m, precisely clipped to align with provincial boundaries.

-

2.

Great Wall Heritage Data (Fig. 2\(\textcircled {2}\)): Our research group developed the Ming Great Wall Cultural Heritage Database [21], a result of over a decade of research. This database integrates Geographic Information Systems (GIS), remote sensing, and computational analysis to provide a detailed spatiotemporal overview of ancient defensive settlements along the Great Wall of China. It includes geospatial, heritage-specific, ecological, socio-economic, and cultural environment data. For this study, the database provided extensive details on wall structures, military settlements, buildings, and associated relics.

-

3.

Water System Data (Fig. 2\(\textcircled {4}\)): We derived this data from Tan Qixiang’s The Historical Atlas of China [20] combining and georeferencing maps from the Ming Dynasty’s capital (Northern Zhili) and Shanxi regions. Using ArcGIS for spatial adjustments, we integrated this historical data with current water system information from Google satellite maps to reconstruct the Ming Dynasty’s water systems in these areas.

-

4.

Military Configuration Data (Fig. 2\(\textcircled {7}\textcircled {8}\)): The organization of military forces, derived from the Chronicles of Four Garrisons and Three Passes - Military Structures - Camps [22], informs this study’s foundation. Additionally, the distribution of garrison grains, as documented in Chronicles of Four Garrisons and Three Passes - Provisions - Garrisoned Supplies, and the allocation of mounts, as outlined in Chronicles of Four Garrisons and Three Passes - Zhenbao Garrison Mounted Forces - Standard Allocations, contribute to our understanding of logistical deployments. Given the incomplete garrison records from Zhenbao Town, this research employs Kriging interpolation, modeled on the methodology presented in Du’s study, to visualize the distribution across the designated study area, identified as [16].

-

5.

Transportation Data (Fig. 2\(\textcircled {5}\)): The data on postal stations was obtained from the Ming Great Wall Cultural Heritage Database developed by our research group. The data on postal routes was derived from the study by Cao, which employed GIS-based surface cost and shortest path analyses, using the atlas of the Ming Dynasty Great Wall Defense as a reference [23].

-

6.

War Data: This data was sourced from the Chronology of Wars in China(vol. 2) [24]. The dataset adheres to three specific criteria: it is well-documented, pertains to the Ming Dynasty era (1368–1644), and encompasses the regions of Hebei Province, Shanxi Province, Shaanxi Province, Beijing City, and the central and western parts of Inner Mongolia Province. Each entry includes the war name, the Gregorian year, and both the ancient and modern names of the locations involved.

Methods

This study is organized into four stages, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

-

1.

Factor Selection and Visualization The initial stage involved conducting a comprehensive literature review to identify factors relevant to war geography, military force and supply logistics, and transportation and communication, which were considered the three aspects for assessing Military Defense Capability (MDC). Additionally, social, political, and military factors were identified as the three aspects for assessing Military Requirement (MR). The AHP-PCA method, combining both subjective and objective approaches, was employed to determine the weights of various indicators for MDC and MR. Subsequently, K-means spatial clustering was applied to visualize the spatial distribution and intensity of these two factors.

-

2.

Model Construction An ordinary least squares (OLS) regression model was employed to establish correlations between MR with the identified MDC factors. Residual values – representing the discrepancy between actual values (derived from the four MR factors) and predicted values from the regression model (based on the nine MDC factors) were visualized to identify areas with disproportionately strong or weak defenses.

-

3.

Model Evaluation The accuracy of the regression model was evaluated by comparing the locations of the Northern Border Wars during the Ming Dynasty with regions exhibiting higher absolute residual values in the OLS model. This comparison provided insights into the primary factors that may have contributed to conflicts between the Ming government and the northern nomads.

-

4.

Explanation The results were visualized within a spatial context, and a clustering analysis of the military settlements was conducted. A resource allocation assessment model for military settlements in the Cold Weapons Era was constructed, aiding in the analysis of the distribution logic and patterns of defense forces along the Great Wall and its military settlements.

Data vertebralisation

All data processing and calculations in this study were performed on the ArcGIS platform, utilizing its built-in tools for spatial clustering and ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. In addition, all data analysis and classification tasks, including k-means clustering and AHP-PCA factor analysis, were conducted using SPSS 26 software.

-

1.

Grid Analysis Grid analysis partitions large-scale datasets into smaller cells, standardizing the spatial scale of all factors, ensuring effective visualization, and providing a broad range of applications in spatial pattern analysis [25, 26]. In this study, the area was divided into a grid system of 3 km by 3 km, comprising 8,407 cells (as shown in Fig. 1). The values of each factor within MDC and MR systems were extracted for each grid, serving as the basic data for cluster analysis. The selection of a 3 km by 3 km grid was based on a comprehensive consideration of the accuracy of the acquired historical data and the significant spatial differences in internal elements attributed to larger grid scales.

-

2.

Normalization Given the diverse dimensions of the evaluation factors, such as spatial and numerical relationships in the evaluation factors, the original data units differ, and their numerical ranges vary greatly. This study employs a normalization method to unify data from different dimensions into the same dimensional unit, ensuring data integrity while preparing for subsequent weight calculation, clustering analysis, and OLS regression analysis [27, 28]. The commonly used method for normalising data transforms the original data into a range of [0, 1] through linearisation, where the minimum value of the data is 0. This means that, regardless of this data’s weights, the minimum result will always be 0. To circumvent the issue of a minimum value of 0, this study employs specific formulae for all factors:

$$ X' = 0.1 + 0.8 \cdot \frac{|x - min(x) |}{|max(x) - min(x) |} $$(1)where X’ is the normalized value in the range [0.1,0.9]; x is the original value; and min(x) and max(x) are the minimum and maximum values of the original value.

Data analysis tools

-

1.

AHP-PCA combined method In this study, a hybrid method combining subjective and objective approaches was employed to calculate the weights. Specifically, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) calculates weights with an emphasis on objectivity. On one hand, PCA condenses weights based on the data’s inherent characteristics [29]. On the other hand, the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) constructs matrices from expert evaluation scores to assess factor importance, mapping these assessments to weight levels. This PCA and AHP combination aims to mitigate AHP’s inherent subjectivity in weight allocation and more accurately capture the data’s true characteristics.

AHP determines the weight value of each indicator through eigenvector normalisation.To ensure decision-making reliability and consistency, the consistency ratio (CR) assesses the elements’ consistency within the judgement matrix. When CR < 0.1, the judgement matrix is deemed to have satisfactory consistency, allowing for the reasonable calculation of model evaluation indicator weights [30, 31].

Weight values for each level were determined by averaging the row weight values based on the calculated weight vector. To ascertain final weights, these averages were multiplied by the corresponding weight pairs at different hierarchy levels. The formulas that follow complete the method description, offering a clearer understanding of the weight calculation process:

$$W=t*Wahp+(1-t) Wpc$$(2)Wahp is the weight obtained from the AHP method and Wpc is the weight obtained from the principal component method. The value of t is between 0 and 1, which depends on the degree of difference between the weights of the indicators of the AHP analysis method, and in this study, t is taken as 0.5, which represents the equivalent influence of subjective and objective weights.

-

2.

K-means In this study, the K-means algorithm clustered nine factors within the MDC system and four factors within the MR system, with all factor data sourced from corresponding grid cells. The optimal number of clusters for MDC was identified using the elbow method. This method pinpoints a moment where adding another cluster fails to significantly enhance data modelling [32].

Through the analysis of clustering results, we can gain a deeper understanding of the strategic considerations and defense priorities at that time, thereby achieving a nuanced comprehension of military strategies in history.

-

3.

OLS Linear Regression Regression analysis is a method used to predict a dependent variable based on one or more independent variables [33]. In the OLS (Ordinary Least Squares) linear regression model, the fundamental principle involves fitting a straight line through data points. The optimal line in OLS regression is achieved when the sum of the squares of the distances from all data points to this line is minimized, expressed as:

$$Y_i=b_0+b_1 x_i1+b_n x_in$$(3)where \(b_0\) is the intercept, \(b_n\) represents the coefficient for the nth independent variable \(x_{n}\). Here, i denotes the number of data points. The goal is to determine the regression model parameters (intercept and slope) by minimizing the residuals, specifically the sum of squares of the residuals, where residuals are the differences between the observed values (\(Y_{n}\)) and the predicted values (\(Y_{n}\)).The coefficient of determination \(R^{2}\) measures the proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by the independent variables, with values closer to 1 indicating a better model fit. This study employs an OLS linear regression model to evaluate the relationship between MR and MDC in the study area, identifying regions with disproportionately high or low defense capabilities from a data-driven perspective.

Factor selection

Factors influencing MDC (explanatory variable)

Military geography is an interdisciplinary field that integrates both natural and social sciences. From a natural science perspective, it examines such as terrain, river systems, and climatic features, which constitute the objective geospatial environment in which wars occur [34]. On the social science side, it includes elements like political systems, economic conditions, military strategies, transportation networks, and population demographics [18, 35], which together form the material and ideological forces of warfare [36]. Building on the research of scholars like Zhou [37], Zhang [38], and Tan [39], this study focuses on three key aspects for in-depth analysis: war geography, military force and supplies geography, and transportation and communication geography. These dimensions collectively provide a comprehensive understanding of the complex nature of military geography (see Table 1,Fig. 4).

Visualization of the factors of the Military Defense Capability (MDC). The map marks the Ming capital, the four hierarchical levels of the Zhenbao Town military settlements (Town City, Road City, Fortress, and Passes), as well as the Great Wall. The defense values are divided into nine intervals, each represented by a different color

-

1.

War Geography

For defense purposes, an elevation of 800 ms (D1) is optimal due to easier construction and adequate height for effective observation and defense capabilities. Proximity to river systems (D2) is ideally around 10 kms, balancing strategic access to water and reducing direct vulnerability; this distance allows citadels to oversee and protect major transport routes, thus enhancing defense against invasions and supporting logistics [8]. For slope considerations (D3), areas with mid to steep slopes are best, providing natural defensive advantages and facilitating surveillance of enemy movements [40].

-

2.

Military Force and Supplies Geography

The geography of military force and supplies, focusing on resource distribution and logistics, is crucial. The number of troops (D4) not only reflects strategic intentions but also provides insights into Ming dynasty military dynamics [37]. The “cantonment system” near Great Wall citadels allowed soldiers to farm nearby wastelands during peacetime, ensuring a self-sufficient food supply and reducing military costs and civilian economic burdens. Two other significant factors are the army provisions (D5), which gauge the capacity to store and supply food, and the distance from the Great Wall (D6), which influences a castle’s strategic and defensive effectiveness due to its proximity to walls, towers, and natural defenses [22].

-

3.

Transportation and communication Geography

Transportation and communication geography explores infrastructure that supports movement and communication in ancient military settings, covering the transportation of armies, supplies, and war information via stations and roads. Extensive road networks in plains facilitate transportation, while in hilly regions, roads follow valley directions. The defense area’s relay system, comprising relay stations, delivery posts, and rush stores, was vital for transporting documents, troops, and supplies (D7). The concept of internal accessibility (D8) assesses each road’s connectivity to relay stations within the system, determining its efficiency [41]. External accessibility (D9) measures proximity to the overall road system, emphasizing the strategic location of citadels near key routes [42].

Factors influencing MR (dependent variable)

In the context of ancient northern nomadic invasions, which were primarily driven by territorial and resource conflicts [43], this study incorporates the factors of county tax payments per unit area (D10) and historical settlement kernel density (D11) into the assessment of MR. These factors are pivotal in understanding the motivations and patterns of predatory warfare, which is closely linked to the level of taxes, the defensive capabilities of other towns along the Great Wall, proximity to the capital city, and the concentration of settlements [8]. The rationale is that invaders typically target areas rich in resources and population. Furthermore, many attacks on Zhenbao Town were politically motivated and aimed directly at capturing the capital city (D12). Hence, the distance to the capital city is also considered a crucial factor in evaluating MR. Additionally, in relation to the joint defense mechanism of Zhenbao Town, its position as part of the inner Great Wall and its strategic location east of Chang Town, north of Xuanfu Town, and west of Datong Town and Shanxi Town should also be considered. In times of war, these towns would collaborate to combat enemy forces [44, 45]. This collective defense strategy implies that the closer the proximity between the inner and outer Great Walls (D13), the less the location would be considered a target for invasion, thereby reducing the overall MR value. This factor is indicative of the synergistic defensive capabilities afforded by the geographical positioning of Zhenbao Town within the broader network of the Great Wall(see Table 2, Fig. 5).

Result

This chapter involves the quantified evaluation of MDC and MR, as well as the spatial regression of both.

Characteristics of the spatial distribution of MDC and MR

In this study, the AHP-PCA synthesis method is employed to combine subjective and objective weights for MDC and MR for each influencing factor. Table 3 presents the weight values for MDC and MR for each factor, assuming equal influence of subjective and objective weights. The AHP weights were determined by Professors Li, Tan, and four additional experts in military settlements or related disciplines, as well as scholars focused on Ming Dynasty history. Each secondary factor was represented in a pairwise comparison matrix, designed to evaluate various impact dimensions. Following standardized comparison principles, matrix diagonals were assigned a value of 1 to uphold reciprocity. A Consistency Ratio (CR) less than 0.1 indicates satisfactory consistency.Furthermore, the spatial overlay function of ArcGIS software was utilized to weight and sum the combined weights of the MDC and MR indicators in the fishing network unit, incorporating the standardized results of each indicator. A cluster analysis was performed on these weighted results, revealing significant geographic variability. This analysis produced a map illustrating the distribution of military defence power and potential in the Zhenbao town region Fig. 6, Fig. 7. The classification and grading of MDC and MR reflect the structural distribution differences of regional MDC and MR. MDC and MR were classified into five grades: Supreme, Advanced, Moderate, Limited, and Minimal, respectively. Obvious differences in area proportions exist between the grades, with MDC results at 21.76\(\%\), 27.55\(\%\), 26.67\(\%\), 16.62\(\%\), and 7.41\(\%\) for the respective grades; and MR results at 27.69\(\%\), 24.86\(\%\), 19.79\(\%\), 17.64\(\%\), and 10.02\(\%\).The overall military defence power in the Zhenbaozhen area falls within Advanced and Limited levels, comprising 54.22\(\%\) of the total; similarly, the overall MR lies at Supreme and Advanced levels, accounting for 52.55\(\%\) of the total.

The analysis results (Fig. 6) indicate that the MDC, particularly that of Baoding Town City, is most prominent, while Road Towns are generally situated in areas of higher-MDC. Comparing the military settlements of the four Roads revealed that ZJG Road settlements were predominantly located in areas with higher-MDC; MSK Road and DMG Road exhibited similar-MDC, albeit slightly inferior to ZJG Road; LQG Road, however, was situated in an area of overall lower-MDC.

The MR analysis map (Fig. 7) shows a gradual decrease in MR from the northeast to the southwest of the Zhenbao Town region, with high-value areas primarily concentrated east of the military settlements, especially in the western parts of Beijing, Baoding, and Shijiazhuang regions. Notably, both DMG Road at the Plugging Arrow Ridge and DMG Road City are situated in high-MR areas, serving as important transport routes from the Shanxi plateau to the central Hebei plain.

Constructing a military resource supply and demand model

To verify the suitability of selected indicators for principal component analysis–that is, their independence–the indicators undergo factor analysis testing with SPSS 26’s Bartlett’s spherical test. The approximate chi-square value from Bartlett’s test (3769.473) and the significance value (0.001**) suggest further analyses are warranted. Consequently, the correlation coefficient matrix significantly differs from the unit matrix. With KMO (Kaiser Meyer Olkin) values of 0.826 (MDC) and 0.682 (MR) exceeding 0.650, the original variables are deemed suitable for factor analysis.

This study investigates the intrinsic patterns of MDC and MR in Zhenbao Town. Utilizing the spatial statistics module of ArcGIS 10.8 software, a comprehensive analysis of MDC in Zhenbao Town was conducted, examining nine variables and their relationship with MR. Residuals from the OLS regression model were analyzed for auto correlation with clustering and Anselin Local Moran ’I outlier analysis, yielding a Moran ’I cluster and significance plot (Fig. 8). The analysis revealed a clustered distribution of the residuals, with a corrected R-squared value of 0.65, indicating the model explains 65.9\(\%\) of the variance in relationship between variables, thus demonstrating high model credibility. The coefficient of an explanatory variable indicates both the strength and the nature of its relationship with the dependent variable. A negative coefficient signifies an inverse relationship with MR, as the dependent variable.

OLS regression results indicated that the coefficients of explanatory variables elucidate the model. All explanatory variables, except elevation, river system, slope, and distance from the Great Wall, exhibited a positive coefficient relationship with military defense. This implies that lower values of elevation, river system, slope, and distance from the Great Wall, post-normalization, correlate with higher military defense potential. Table 4 presents the coefficients, significance, and Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) of the explanatory variables. VIF measures the extent of multicollinearity in OLS regression analysis. Each VIF value was found to be less than 6, indicating no redundancy or multicollinearity among the explanatory variables.

This analysis revealed significant clustering patterns within the data. The spatial clustering process, facilitated by ArcGIS, enabled the categorization of spatial defense levels into three distinct categories: high-high (HH), not-significant (NS), and low-low (LL).The HH category, represented in black, highlights regions where the defense capability falls short of the regression line’s predicted potential. These areas should be understood as having a critical deficiency in defense capability(MDC>MR). Conversely, the LL category, shown in blue, indicates areas where the defense capability significantly surpasses the potential value predicted by the regression line. These areas could be interpreted as having an excess of defense resources(MDC < MR). Finally, the NS category, depicted in grey, denotes areas where clustering is not statistically significant.Import the recorded conflict locations between the Ming Dynasty government and the northern nomadic tribes, including their latitude and longitude, into ArcGIS 10.8 and visualize them. This will result in the green points shown in Fig. 8. The larger the green point, the more frequent the wars occurred at that location. The analysis of residuals and outlier evaluation revealed that 19% of conflicts between the Ming dynasty and Mongolia occurred in the low-low (LL) region, including Shijiazhuang City, Zhengding County, Laiyuan County, and Lingqiu County. Furthermore, 38% of wars took place in the high-high (HH) area, encompassing Wutai County, Fangshan District, Chengde City, Yuxian County, and Changping County. Additionally, 43% of the conflicts occurred in the not-significant (NS) region, which includes Xingtai City, Wangdu County, Yi County, and Yanqing County.

K-means cluster analysis and spatial auto-correlation testing were applied to three secondary factors (B1-B3) related to military defence capacity. This preliminary analysis revealed spatial clustering tendencies in all these factors, laying the groundwork for a more detailed K-means clustering analysis. The optimal number of clusters was determined using the elbow rule, which analyzes the linear graph of aggregation coefficients.The key insight gleaned from this graph, as illustrated in Fig. 8, is the point at which the decline in the trend of the line begins to plateau. Specifically, when the classification of military defence capacity reaches seven categories, the downward trend of the line graph decelerates. This observation suggests that the most appropriate number of military defence capacity classes is seven. Following this determination, a detailed K-means clustering analysis was conducted. The results were subsequently visualized in ArcGIS, as shown in Fig. 9. This visualization effectively highlights the significant spatial aggregation within most identified clusters, reinforcing the K-means analysis findings and offering a more accessible insight into the spatial distribution and clustering of MDC.

The analysis identifies Baoding Town as a crucial defense point within the military settlement system, although its flat terrain poses challenges to defensive strategies. The town is fortified with four Road cities, each recognized for robust defense capabilities.Notably, ZJG Road is distinguished by its effective defense, as demonstrated by its frequent involvement in Ming-Mongolian conflicts. The imperial court frequently deployed reinforcements to strengthen the fortresses along ZJG Road. Similarly, MSK Road, sharing features with DMG Road, displays substantial but slightly lesser defensive capabilities. Historically, MSK Road has been a pivotal military bastion, safeguarding the capital and constituting a vital defense line in the northeastern region. It is strategically positioned in the mountains, overseeing major north–south transportation corridors.

Adjacent to ZJG Road, Dalongmen Fort City is strategically located yet vulnerable in the southwest region. This area, frequently targeted by Mongolian cavalry for southern detours and pincer attacks on the capital, is critical for defense purposes. The defense emphasis on DMG Road focuses on the Langyakou area, which represents the strategic core of the region.

In contrast, LQG Road is less effective defensively due to its expansive defense zone and stretched defense line. The key defense area of LQG, around Guguan, oversees the principal passage from Taiyuan to Zhending (present-day Shijiazhuang), a crucial bottleneck. Mongolian forces typically conducted harassment along LQG Road to disrupt the main forces, without making significant incursions into Beizhili. Additionally, LQG Road exhibits considerable geographical variation from north to south, characterized by distinct terrain features.

Discussion

This study employs the Analytic Hierarchy Process-Principal Component Analysis (AHP-PCA) method for weight determination, and K-means clustering to analyze the spatial patterns of Military Defense Capability (MDC) and Military Requirement (MR). The Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression model is applied to identify regions with excessive or insufficient defense capabilities during historical periods, and the factors contributing to this phenomenon are explored. These findings not only highlight the spatial clustering of military force distribution but also provides new insights into the strategic intentions of military heritage and the influence of geographic factors.

Methodological concerns

Historical data quantification methods in the study of ancient military settlements have primarily been applied to assess the defense efficiency and scope of Ming Dynasty coastal defense settlements in Zhejiang [13, 39], with fewer applications to Ming Dynasty Great Wall military settlements. Wang identified the overall distribution pattern of coastal defense capabilities by determining weights and constructing Voronoi diagrams [10]. Wu assessed the accessibility of Ningbo’s naval defense system by reconstructing it through a hierarchical evaluation model and historical maps [9].However, these methods have been less frequently applied to military settlements along the Ming Dynasty Great Wall. This study provides a new perspective by quantifying MDC and MR within defense zones and evaluating the effectiveness of technical methods for assessing military resource supply and demand. It addresses challenges faced in previous research, such as determining the weight of multidimensional data on defense capability and interpreting historical data models [8]. Additionally, this method presents several advantages. Firstly, the combined AHP-PCA approach accurately assigns weights to various influencing factors of MDC and MR, providing an effective assurance for analyzing complex military defense systems. By categorizing MDC and MR into five distinct levels and conducting area proportion analysis, the disparities between them across different levels and spatial distributions are revealed. Secondly, the adoption of quantitative methods coupled with GIS technology enhances research transparency, improves data visualization, and renders the research method applicable to other historical military settlements, offering innovative perspectives beyond qualitative research and historical experience for analyzing the heritage of Great Wall settlements. Thirdly, the OLS linear regression method, commonly used in economics, ecology, geography has seen limited application in historical analysis. This study, by integrating previous and experimental data quantification, marks the first application of this method in the study of military settlements, supporting a fresh interpretation of historical data.

Insights for the OLS model

Zheng’s research focused on the defensive strategies of Zhenbao Town [46], while Xie examined Zhenbao Town’s formation and development [19]. Our study further validates these conclusions by analyzing the distribution of military requirements and historical conflict events. This study explores the strategic resource allocation of Ming Dynasty military settlements along the Great Wall, uncovering the complex interactions between resource distribution, geographical factors, and strategic requirements.Previous research has often struggled to capture the full complexity of these spatial environments. Settlements were often built in strategically important locations, close to the Great Wall, with steep and rugged terrain. This is particularly evident in areas like ZJ and DM, where the use of natural gorges to form defensive sequences is a prominent feature [45]. Studies on Zhejiang coastal defense settlements have identified terrain complexity as one of the most critical factors. In areas with complex terrain, settlements are easier to defend and result in fewer troop losses [47]. Existing studies have focused more on terrain factors. Research by Zhang, Duan, and others suggests that the distribution of garrisons is closely linked to the natural geographical environment, with site selection being strongly influenced by mountains, water, transportation routes, and proximity to the Great Wall [6, 7]. Our study reinforces these findings, demonstrating that the high defense capability (MDC>MR) in these areas is closely relevant to their rugged terrain, which allows allocating less defense resource to successfully repel more powerful enemy attacks. This further underscores the crucial role of terrain in defensive planning.

This research identified significant regional disparities in MDC and MR. Notably, Baoding City, as the central town of Zhenbao Town, is situated on the plains but plays a vital role in supporting military operations and cultivation. It provides essential military support to the capital while maintaining substantial MDC. The strategic deployment of defenses along Baoding and collaborative fortification efforts with adjacent areas underscore the necessity of enhancing fortifications at critical sites, consistent with Zhou’s insights on the role of fortress cities in safeguarding the capital [11]. Moreover, there are areas within Zhenbao Town where the MDC is lower than the MR (LL areas), such as Shijiazhuang City, Zhengding County, and Laiyuan County. These areas, crucial for military strategy, have records of both repelling and succumbing to enemy assaults [24], frequently engaging in conflicts with northern nomadic tribes. The capital region, characterized by both high-MDC and high-MR (HH areas), aligns with historical encounters during the Ming Dynasty’s conflicts with Mongols in the Zhenbao Town area [48]. The formidable terrain contributes significantly to its defense. Tumu Fort’s positioning within the HH zone likely results from the dynamics between military settlements and warfare activities. Post the Tumu Crisis, Zhenbao Town saw significant construction activities aimed at bolstering the Great Wall’s defenses, highlighting that warfare acts as a catalyst for the ongoing enhancement of military settlements [3, 16].

Previous studies has primarily concentrated on the military defense architectures of historical settlements, with less emphasis on quantifying troop numbers, logistical support, and human aspects such as village configurations. To detail the reasons some areas in Zhenbao Town, scene of historical conflicts, are situated in regions with disparities between MR and MDC, this paper will focus on three main aspects. The first aspect is geographical factors. Typically, passes and fortresses were strategically situated in deep ravines, gorges with significant mountain and water features, or at locations controlling rivers, streams, and bays, enabling defense against larger enemy forces with fewer troops. The second aspect concerns human factors, notably economic and trade elements. Locating passes and fortresses along main traffic routes facilitates military management, goods transportation, and benefits local populations. Yuxian County, rich in rivers and valleys, served as a crucial transport hub during the Ming Dynasty. Alongside fortresses, the Ming government established several post stations, connecting the north and northwest regions and ensuring prompt battlefield information transmission during wars. Consequently, despite Yuxian’s steep terrain, its fortresses’ placement on main traffic routes–due to logistical considerations–resulted in insufficient defense capabilities. The third aspect involves political factors. During the Ming-Mongolian War, capturing Beijing, the Ming Dynasty’s capital, held considerable significance for Mongolia. Capturing Beijing enabled Mongolia to further consolidate its dominance in the northern region. Furthermore, Beijing’s capture represented a significant military triumph for the Mongols, boosting their army’s morale and combat efficacy, potentially precipitating the Ming Dynasty’s collapse. Currently, regions such as Chengde, Tumu Fortress in Huailai, Hebei Province, and the fortresses in Fangshan District of Beijing remain overly reliant on their strategic potential yet under-defended, a condition directly tied to the historical political importance of the Ming Dynasty’s capital.

Significance and limitations

The significance of adopting the tools and models in this study lies in their provision of more rational technical support for large-scale regional historical and cultural resource management, research, and preservation efforts, with a primary focus on the excavation of heritage values. This study aims to improve the overall knowledge of different military settlements and to enhance the historical and cultural value of ancient military heritage [49]. It emphasizes the key role played by digital models of ancient environments in the analysis and understanding of the spatial structure of ancient heritage, and it explores methods for the digital preservation of 2D historical maps. Additionally, this digital investigation into defense mechanisms derived from historical military settlements offers valuable insights into model construction aimed at improving the safety and protection of modern cities [50], optimizing resource allocation, and bolstering the defense of critical areas. This study assists heritage conservationists in prioritizing locations along the Great Wall and its military settlements that require greater attention [13]. It ensures that both historically significant and vulnerable sites receive the necessary protection, providing valuable insights for academic research and public heritage management practices.

This study explores the relationship between the supply and requirement of military defense forces in ancient times, identifying several challenges that future research must address. The study’s scope, which includes the historical Zhending and Baoding prefectures and aligns with modern administrative divisions, requires further validation due to its speculative nature [51]. Concerning the selection of factors for evaluating MDC and MR, the limitations of existing literature and the challenges of quantification have led to an incomplete selection, highlighting the need for more granular and precise historical data [52].Moreover, the unpredictable nature of historical warfare has led this paper to compare the residuals of the OLS regression model with border conflicts in an attempt to identify patterns and validate them with historical data. However, this task is complicated by the inherent randomness of historical events. The accuracy and suitability of the OLS regression model require improvement, and it is advisable to explore other regression models that account for spatial location, such as GWR and MGWR, is advisable [53].Furthermore, it is recommended to enhance comparative studies of military settlement resource allocation strategies across different historical periods and regions. Such comparative research can provide a more comprehensive understanding of historical trends in military resource allocation and their relationship with geographic environments and political contexts. This, in turn, would offer richer theoretical and methodological support for studies in historical geography.

Conclusions

This study proposes a resource allocation model for ancient military settlements, focusing on the Zhenbao Town of the Ming Great Wall. This model is significant because it provides a novel approach to understand the heritage of Great Wall settlements from a supply and requirement perspective, considering the complex influences of mountainous terrain. Previous studies have primarily relied on subjective assessments, limiting their ability to objectively evaluate Military Defense Capability (MDC) and Military Requirement (MR) in defense zones. In contrast, our research introduces a more comprehensive and standardized method for measuring MDC and MR, incorporating quantitative metrics and spatial analysis. By digitizing historical data and analyzing military defense capability through the lenses of war geography, military force and supplies geography, and transportation and communication geography – and military requirements from three aspects – social factors, political factors, and military factors, we focus on examining the spatial distribution relationship between MDC and MR in Zhenbao Town of the Ming Great Wall. Using the OLS model, we identify regions with excessive or insufficient defense capabilities and explore the reasons for defense capability mismatches from cultural, geographical, and political perspectives. This study draws several key conclusions:

-

(1)

The study area exhibits area shows significant regional differences in MDC and MR. Baoding Town City has the highest defense strength, with all road cities situated in areas of elevated defense capability. Despite its plain terrain, which traditionally is less conducive to defense, Baoding Town City remains a crucial military settlement point, a finding consistent with previous research. MR gradually diminishes from northeast to southwest, with the western Beijing, Baoding, and Shijiazhuang areas representing high-value regions. Notably, these regions frequently witnessed conflicts during the Ming-Mongolian wars, aligning with historical records.

-

(2)

In the Zhenbao Town area, MDC levels are predominantly Advanced and Limited, comprising 54.22% of the total; while, MR levels reach Supreme and Advanced, representing 52.55% of the total. Zhenbao Town’s establishment aimed to counter invaders from Shanxi and protect the capital, highlighting its military importance.

-

(3)

Among the documented Ming-Mongolian conflicts, 19% occurred in the LL region (MDC < MR) near Beijing, emphasizing the strategic proximity to the capital. The capture of Beijing promised substantial military, political, and economic gains for Mongolia, indicating a higher military requirement value. Additionally, 38% of conflicts occurred in the HH region (MDC>MR), strategically positioned to control key waterways, enabling effective defense with fewer troops due to the treacherous terrain.

-

(4)

High-MDC settlements, closely correlated with war geography factors, were positioned at the forefront of battlefields but suffered from inadequate troop and logistics reserves, relying on challenging terrain for defense. Medium-MDC settlements demonstrated stronger correlations with troop support and logistics factors, often located on moderate slopes. Low-MDC settlements struggled with transportation and communication, where the viability of stagecoach routes significantly influenced command and supply operations.

The digitization of historical data presents significant potential for applications. The military resource allocation assessment model developed in this study for Zhenbao Town has proven to be a tool for optimizing resource allocation and enhancing defense in critical areas. This model has been instrumental in gaining a deeper understanding of the spatial distribution characteristics of historical MDC and MR, particularly in assessing military resource supply and requirement in the Zhenbao Town. The findings are crucial for the formulating more effective policies concerning cultural heritage and environmental protection. Firstly, the results provide a solid foundation for exploring the spatial distribution of military resources during the Cold Weapon Era. Secondly, considering the urgency and scientific basis of heritage preservation, this tool offers valuable guidance for heritage protection policies.

Data availibility

All the data and materials supporting the results and analyses presented in this paper are available upon request. The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- MDC:

-

Military Defense Capability

- MR:

-

Military requirement

- MSK:

-

Mashuikou

- DMG:

-

Daomaguan

- LQG:

-

Longquanguan

- ZJG:

-

Zijingguan

References

Heritage U, Rii P. Convention for the safeguarding of the intangible cultural heritage. Paris: Unesco Org; 2003.

Li Y, Zhang Y, Li Z. Research on defence system and military settlement of the great wall in the ming dynasty. Archit J. 2018;5:69–75.

Ziyao Y. Study on the defense efficiency of the coastal defense military settlements in ningbo in the ming dynasty. PhD thesis, Tianjin University. 2019

Wuchao K. The military geographical viewpoints in on warfare. Human Geogr. 1991;6(4):29–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdu013I2014.

Yu A. Military-economic interaction theory. Beijing: Chinese Economy Press; 2005.

Yukun Z, Songyang L, Lifeng T, Jiayin Z. Distribution and integration of military settlements’ cultural heritage in the large pass city of the great wall in the ming dynasty: a case study of juyong pass defense area. Sustainability. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137166.

Shile D, Qing L. Research on the distribution and site selection of military settlements of the ming great wall in ningxia military town. Landsc Archit. 2021;28:107–13. https://doi.org/10.14085/j.fjyl.2021.06.0107.07.

Yan L, Wang Y, Yukun Z, Zhe L. Comparison between the silk road settlement and the ming great wall settlement. New Architecture 2020; 127-131

Yukun Z, Bei W, Lifeng T, Jiayi L. Information visualization analysis based on historical data. Multimed Tools Appl. 2022;4:81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-021-11030-8.

Yinggang W, Lifeng T, Zao Z, Huanjie L, Jiayi L, Yukun Z, Mengqi M. A quantitative evaluation model of ancient military defense efficiency based on spatial strength - take zhejiang of the ming dynasty as an example. Herit Sci. 2023;11(1):246. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-023-01098-w.

Chao Z, Kexin W, Chuli H, Jing L. Research on the layout and site selection of the military settlements in guizhou in the ming dynasty. Chin Landsc Archit. 2022;38:109–14.https://doi.org/10.19775/j.cla.2022.12.0109

Wang L. Spatial analysis of the great wall ji town military settlements in the ming dynasty: Research and conservation. Ann GIS. 2018;24(2):71–81.

Lifeng T, Bei W, Yukun Z, Shuaishuai Z. Gis-based precise predictive model of mountain beacon sites in Wenzhou, China. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):10773. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-15067-z.

Jie H, Meng Y. Spatial humanities in landscape history studies in the digital era. Landsc Archit. 2017;11:7. https://doi.org/10.14085/j.fjyl.2017.11.0016.07.

Sui DZ. Gis, cartography, and the “third culture”: Geographic imaginations in the computer age. Prof Geogr. 2004;56:62–72.

Yumin D, Wenwu C, Kai C, Zhigian G, Guopeng W, Xiaofeng R. An exploration of the military defense system of the ming great wall in qinghai province from the perspective of castle-based military settlements. Archaeol Anthropol Sci. 2021;13(3):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-021-01283-7.

Baolin M. Research of theory and method of military requirement assessment. J Nanjing Univ Sci Technol. 2020;44(5):13–24. https://doi.org/10.14177/j.cnki.32-1397n.2020.44.05.017.

Goyal S, Vigier A. Attack, defence, and contagion in networks. Rev Econ Stud. 2015;81:1518–42.

Dan X, Minghao Z, Lifeng T. Study on the spatial characteristics of defensive settlements in zijingguan defence area of the great wall of the ming dynasty based on gis. China Cultural Heritage 2020;6:97–104.

Qixiang T. Concise Historical Atlas of China. Beijing: Sinomap press; 1991.

Yuku Z, Lingyu X, Yan L, Jie H. Database construction and application of the defense system of ming great wall from the perspective of spatial humanities. Tradit Chin Archit Gard. 2019;2:7.

Liu X. The History of the Four Towns and Three Passes. Zhengzhou: Zhongzhou Ancient Books Publishing House; 1991.

Yingchun C, Yukun Z, Haoyan Z. Gis-based road rehabilitation of the map on the datong zone of the great wall defense system in ming dynasty. J Agric Univ Hebei. 2014;37(2):7.

Group CMHW. Chronology of Wars in China. Beijing: Chinese People’s Liberation Army Press (PLAP); 2003.

Li Jiangsu LX, Wang Xiaorui. Spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of chinese traditional villages. Econ Geogr. 2020;40(02):143–53. https://doi.org/10.15957/j.cnki.jjdl.2020.02.016.

Jing W, Xiaohuan Y, Ruixiang S. Spatial distribution of the population in shandong province at multi-scales. Prog Geogr. 2012;31(02):176–82. https://doi.org/10.11820/dlkxjz.2012.02.006.

Shuangjin L, Shuang M, Yongmin Z. Spatial patterns of the mismatch degree between the accessibility and the visiting preference for all parks in the main city of zhengzhou. Areal Res Dev. 2019;38(02):79–85.

Hongan W, Janjn J, Je Z, Haing Z, Li Z, Li A. Dynamics of urban expansion in xi’an city using landsat tm/etm+ data. Acta Geogr Sin. 2005;01:143–50.

Taohong Z, Kunihiko Y. Environmental vulnerability assessment using remote sensing and gis: a case study in daxing’anling area, china. J Japan Soc Photogramm Remote Sens. 2016;55(5):314–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.03.039.

Mengyun Z, Cai Yongli ZR, Jian L, Xuejun S. The tempo-spatial pattern of regional ecological vulnerability before and after the establishment of national nature reserve in helan mountain of ningxia. Ecol Sci. 2019;38(05):78–85.

Taohong Z, Yaxuan C, Peng C, Jiafu L. Evaluation of eco-environmental vulnerability in jilin province based on an ahppca entropy weight model. Chin J Eco-Agric. 2023;31(09):1511–24.

Xiaomeng W, Jin W, Qing Z. Identification of hollowing phenomenon in commercial space of six district of beijing based on checking-in data. Urban Dev Stud. 2018;25(02):77–84.

Zhihao F, Imran A, Assefa F, Ahmad DM, Halefom TA, Zewdu BA, Ebrahim SE. Identification of potential dam sites using ols regression and fuzzy logic approach. Environ Sci Eur. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/jins.2022.11.139.

Rubio-Campillo X, Cardona FX, Yubero-Gomez M. The spatiotemporal model of an 18th-century city siege. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439314558559.

Arkush E, Stanish C. Interpreting conflict in the ancient andes. Curr Anthropol. 2005;46:3–28.

Wang J. Differentiation and focus in the development of military surveying and mapping and military geography. J Geomat Sci Technol. 2017;34:111–9.

Zhou R, Zou Z. A tentative analysis of china’s historical military geography studies. Military History 2017;58-63.

Yan L, Yukun Z, Zhe L. A study of the defense system and military settlements of the ming great wall. Archit J. 2018;5:7.

Lifeng T, Huanjie L, Jiayi L, Jiayin Z, Pengfei Z, Yukun Z, Shuaishuai Z, Shenge S, Tong L, Yinggang W. Influence of environmental factors on the site selection and layout of ancient military towns (zhejiang region). Sustainability. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052572.

Li Yan SX, Yaqin Z. The geographical landscape model of military settlements in the great wall of the ming dynasty. Landsc Archit. 2023;30(2):97–104.

Zhibin Z, Cuicui Z. A review of research on regional and intra-city accessibility and its applications. Rec Dev. 2016;3:6.

Gao W, Ouyang Y, Zhao M, Gao Y. A review of public service facility accessibility measurement methods. Acta Sci Nat Univ Pekin. 2023;59(2):344–54.

Xiaoyun L, Yu Y, Yi L. The historical evolution and influence mechanism of man land relationship in china. Geogr Res. 2018;37:1495–514.

Yingchun C, Yukun Z. Spatial distribution of the military settlement of the great wall in ming dynasty based on voronoi diagram. J Hebei Univ (Nat Sci Edit). 2014;34(2):129.

Yukun Z, Songyang L, Yan L. Overall layout and joint defense mechanism of the inner and outer three passes about the great wall of the ming dynasty. City Planning Review. 2021.

Yuchen Z, Yukun Z, Yan L. Analysis on the spatial layout and natural topography of ming zhenbao town military defense system. Tradit Chin Archit Gard. 2023;5:118–22.

Lifeng T, Jiayin Z, Yukun Z. The applications and advantages of fractal theory in the study of traditional military settlements- taking the great wall and coastal defense settlements of the ming dynasty for example. Urban Environ Design. 2023. https://doi.org/10.19974/j.cnki.CN21-1508/TU.2023.08.0346.

Wuqiang C. Hongwu period of the ming dynasty characteristics of war on mongolia in temporal and spatial distribution. Northern Forum. 2014;06:114–8. https://doi.org/10.13761/j.cnki.bflc.2014.06.017.

Raffaella DM, Francesca G, Chiara M. Digital documentation of fortified urban routes in pavia (italy): territorial databases and structural models for the preservation of military ruins. J Digit Doc. 2020;13(2):124–36. https://doi.org/10.4995/FORTMED2020.2020.11518.

Tassilo G, Jürgen D. Abstract representations for interactive visualization of virtual 3d city models. Comput Environ Urban Syst. 2009;33(5):375–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2009.07.003.

Gui M, Kaiyong W, Fuyuan W, Yaojia D. The research of administrative division of china in the past 30 years: progress, implications, and prospect. Prog Geogr. 2023;42(05):982–97.

Bendor J, Shapiro JN. Historical contingencies in the evolution of states and their militaries. World Polit. 2019;71(1):126–61.

An R, Wu Z, Tong Z, Qin S, Zhu Y, Liu Y. How the built environment promotes public transportation in wuhan: a multiscale geographically weighted regression analysis. Travel Behav Soc. 2022;29:186–99.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the Liuhe Studio of the School of Architecture, Tianjin University, for providing information on the Zhenbao Town settlements of the Ming Dynasty.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Quantitative Research on the formation composition of the traditional villages in Taihang mountain, grant number 51978441.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Jinni Bai, and Junjie Bian; methodology, Junjie Bian; software, Junjie Bian; validation, Junjie Bian, Jinni Bai, and Zhao Wang; formal analysis, Jinni Bai, Junjie Bian, and Zhao Wang; investigation, Jinni Bai; resources, Jinni Bai, Junjie Bian and Zhao Wang; data curation, Junjie Bian; writing-original draft preparation, Jinni Bai; writing-review and editing, Jinni Bai; visu-alization, Junjie Bian; supervision, Sinan Yuan; project administration, Jinni Bai; funding acquisition, Sinan Yuan. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no Competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bai, J., Bian, J., Wang, Z. et al. Resource supply and demand model of military settlements in the cold weapon era: case of Zhenbao Town, Ming Great Wall. Herit Sci 12, 389 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01496-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01496-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Study on the subsidiary border wall and its siting layout of the Ming Great Wall

npj Heritage Science (2025)

-

Integrity protection of the Chang Zhen Great Wall heritage corridor based on minimum cumulative resistance

npj Heritage Science (2025)