Abstract

Cultural diversity conservation is crucial for global sustainability, especially in rural areas facing challenges such as shrinking settlements and integration into nature reserves. However, existing research lacks discussion on how to establish cultural diversity conservation areas while considering the trade-offs with nature reserves. To address this gap, we employ the SCP method to develop a planning framework that balances ecosystem service benefits for nature conservation with the effectiveness of cultural diversity conservation, applied in rural Southwest China. Our findings indicate that overly ambitious or conservative conservation goals hinder cultural diversity conservation, whereas a value-based scenario enhances conservation effectiveness and reduces conflicts with rural natural ecosystems. We propose rural cultural diversity conservation networks comprising 9 cultural diversity areas, 33 core conservation areas, and 233 subcatchments. Compared with existing systems, our new conservation networks improve effectiveness by 29.62% and reduce the impact on the ecosystem service benefits of ecological conservation by 23.65%. These findings provide guidance for global cultural diversity conservation planning and sustainable development across various regions and scales.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Like biodiversity conservation planning, cultural diversity conservation planning is a key pillar of global sustainable development [1], but it has not received adequate attention [2]. In advancing sustainable development, we encounter the intriguing challenge of balancing the ecological importance of an area with its cultural significance. This is because in many quickly urbanizing countries and regions, numerous rural human settlements are quickly shrinking, hollowing out, and even reverting to wilderness [3]. On the one hand, a reduction in human disturbance can lead to increased ecological opportunities, enhancing nature’s contributions to people, such as ecosystem functioning and habitat quality [4, 5]. On the other hand, the disappearance of rural settlements inevitably leads to the loss of the cultures that they harbor, posing a significant threat to cultural diversity [6]. Therefore, considering the trade-off between ecological opportunities and cultural benefits in rural areas is crucial when exploring cultural sustainability. How can effective conservation planning for cultural diversity be achieved at a low ecological opportunity cost? This aspect has often been overlooked in previous research.

Cultural heritage reflects the values of cultural sustainability and the core of local identity in different regions [7, 8]. The cultural heritage conservation efforts represented by the UNESCO World Heritage List have emerged as a guiding force in the global conservation of cultural diversity [9]. Various countries and regions have also established their own cultural heritage conservation systems [10, 11] and constructed spatial networks for conservation [12,13,14]. In vast rural areas, a large amount of richly varied and representative human cultural heritage [15] is important for regional and global cultural diversity. In global spatial planning practices, shrinking rural human settlement areas are often utilized to enhance ecological benefits as a policy approach [16, 17]. However, how to maintain cultural diversity while meeting ecological conservation policies requires addressing the trade-offs between ecological opportunities and cultural diversity conservation outcomes in rural areas. The importance of rural cultural heritage has increased considerably in recent years with the introduction of concepts such as “cultural landscape” [18] and “rural landscape” [19]. However, rural cultural heritage is still not on par with urban heritage. Therefore, an exploration of the conservation of cultural diversity, with rural cultural heritage as the main theme, is necessary to determine rational ways to delineate the space for conserving rural cultural diversity. This exploration is crucial for maintaining global cultural sustainability.

The rural cultural heritage space represents a social-ecological system coupled with historical cultural resources and the regional environment, necessitating integrated regional conservation [20]. Internationally, the Recommendations concerning the Safeguarding of Beauty and Characteristics of Landscapes and Sites [21], the Venice Charter [22], and the Nara Document on Authenticity [23] emphasize the need to protect the integrity and authenticity of heritage objects and their environments through holistic and continuous conservation networks. In China, cultural heritage conservation efforts are primarily carried out based on administrative divisions. For instance, the Housing and Urban–Rural Construction Bureau and the Ministry of Finance establish demonstration counties (cities and districts) for the centralized and continuous conservation and utilization of traditional villages to promote the conservation of rural cultural heritage. The Ministry of Culture and Tourism has delineated cultural ecological conservation areas (experimental areas) to focus on intangible cultural heritage and holistically safeguard regional cultural forms. However, the use of administrative regions as spatial units for conservation leads to decentralized management and dispersed conservation, which increase conservation costs and create implementation challenges [24].

Currently, regional conservation planning research focused on rural cultural heritage primarily determines the boundaries of conservation areas through hot spot analysis [25], kernel density analysis [26], spatial risk assessment [27], and least-cost path analysis [28]. However, the integrity of planning units and the comprehensiveness of conservation features need improvement, and the impact on rural ecosystems requires further exploration [29]. In these aspects, the systematic conservation planning (SCP) approach can offer substantial assistance.

SCP [30] is a suite of methods used to identify and design conservation areas. The model comprehensively considers the conservation targets of the features and the size, connectivity, and boundary length of the conservation areas. The model also reflects the other aspects of the trade-offs required to achieve conservation targets by setting conservation costs. That is, the desired conservation targets can be attained with the minimum expenditure of resources, such as the lowest ecological opportunity cost [31]. Over the past two decades, tools for SCP, including C-Plan [32], Marxan [33], ResNet [34], Sites [35], Zonation [36], Consnet [37], and CAPTAIN [38], have continually evolved. SCP has been widely applied in areas such as biodiversity conservation [39,40,41], carbon conservation planning [42], ecosystem service management [43], habitat management [44], landscape restoration [45], land use planning [46, 47], and ecological conservation planning [48,49,50]. However, research concerning cultural diversity is limited.

Based on this background, we drew inspiration from the principles and procedures of SCP by constructing a methodology for planning cultural diversity conservation networks. This approach can balance the effectiveness of cultural diversity conservation in rural areas with the potential ecosystem services value (ESV) in a low-cost, low-ecological intervention manner. This will reduce the impact of cultural diversity conservation on rural ecosystem conservation and promote cultural sustainability. We apply this methodology to the cultural diversity conservation planning of rural Southwest China and conduct an empirical study.

Materials and methods

Study area

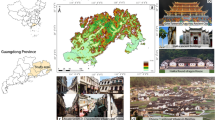

Southwest China is one of the seven geographical divisions of China and comprises the provinces of Sichuan, Yunnan, and Guizhou; the municipality of Chongqing; and the Xizang Autonomous Region, with a total area of approximately 2.33 million km2 (Fig. 1). The region represents one of the most culturally diverse areas in China and holds significant value for exploring the conservation of rural cultural diversity [51]. Characterized by high mountains, canyons, and plateau hills, the region’s topography defines the spatial differentiation of rural human settlements. Various ethnic groups inhabit this area, and they endow the rural heritage with distinctive local characteristics and a rich plurality. However, frequent natural disasters, the weak ecological carrying capacity of the region, and the introduction of urbanization and industrialization in recent years have led to rapid changes in the cultural identity of the region. These problems pose a great threat to rural cultural diversity and sustainability.

Additionally, this region is one of China’s primary ecological security barriers [52] and is a crucial area for biodiversity [53]. Reserves such as Giant Panda National Park, Sanjiangyuan National Park, and the Cangshan Erhai National Nature Reserve within this region offer vital ecosystem services both locally and globally [54]. Amid China’s ongoing territorial spatial planning, rural areas in this region grapple with the complex task of balancing “ecological services,” “cultural conservation,” and potentially, “urban development.” Numerous areas have been earmarked as core zones of nature conservation areas, prompting a gradual reduction in human activity levels. This strategy is appropriate for rural areas with limited cultural value that are also undergoing depopulation. However, in Southwest China, it is essential to consider the conservation of numerous cultural heritage sites with unique value. Consequently, our focus on cultural diversity conservation in Southwest China serves as an exploratory response to the trade-off between the ecological opportunities and cultural benefits faced by cultural sustainability.

Methodological framework

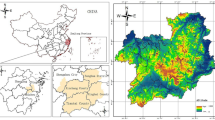

This study referenced the process of system conservation planning [30] and established the method framework illustrated in Fig. 2. The specific steps included the following. (1) The types of rural cultural heritage in Southwest China were identified, and a spatial database of rural cultural heritage in Southwest China was constructed with subcatchments as the planning unit. (2) The main parameters and determination methods of Marxan software were clarified, and four scenarios were established according to the heritage value, conservation status, and conservation vision. (3) By comparing and evaluating the results of conservation planning under different scenarios, the best conservation plan with “high feasibility” was selected as the core conservation area (CCA). In addition, the more macroscopic rural cultural diversity areas (RCDAs) were further divided to form spatial networks for the conservation of rural cultural diversity.

Principles of the method

Our research methodology integrates various principles of SCP [55]. (1) Representativeness includes safeguarding the rural cultural heritage emblematic of local customs and distinctive regional features. (2) Cost-effectiveness encompasses maximizing conservation outcomes at minimal expenditure, thus minimizing conservation-related conflicts. (3) Adequacy involves guaranteeing the achievement of various conservation targets anchored in the heritage value and conservation levels while locking in critical areas and excluding uncontrollable high-threat areas based on the current conservation status. (4) Finally, compactness includes identifying an appropriate boundary length-to-area ratio via SCP software to form cohesive and compact conservation networks for rural cultural heritage conservation, thereby reducing boundary management costs and mitigating adverse edge effects. By adhering to these principles, the framework aims to ensure the integrity of regional-scale networks to conserve rural cultural heritage and achieve a situation in which “the whole is more than the sum of its parts.”

Division of planning units

We used subcatchments, the basic units of human settlement, as planning units, thereby linking cultural diversity conservation planning with specific geographical areas [56]. A subcatchment represents a relatively integrated human-land-coupled system in which the settlements within the subcatchment share roughly consistent cultural characteristics, historical developments, and ecological settings [57]. Using subcatchments as planning units not only protects cultural diversity itself but also emphasizes the holistic conservation of rural human-settlement environments. Based on 1:1000 m and 1:90 m digital elevation data from China (https://www.resdc.cn) within the ArcGIS framework, we first delineated catchments across the terrestrial region of China. For the raster data of each catchment, we sequentially applied fill, flow direction, flow accumulation, raster calculator, stream link, and watershed operations. Finally, the catchments were merged, and topological relationships were established, resulting in a total of 8209 subcatchments. The smallest subcatchment covers an area of 77.52 km2, while the largest subcatchment covers an area of 1954.58 km2, with an average area of 240.87 km2.

Selection of conservation features

Because cultural heritage is both the foundational cornerstone [23] and a significant manifestation [58] of cultural diversity, we chose various types of rural cultural heritage as conservation features. Cultural diversity is reflected in religion, beliefs, customs and traditions, languages, food, arts, values, and the spatial and morphological characteristics of rural settlements [56]. According to the dimensions of cultural diversity, rural cultural heritage encompasses village and town settlements; cultural landscapes such as agricultural and water heritage, which elucidate human-nature interactions; and intangible cultural heritage rooted in rural areas, which comprises unique knowledge, techniques, products, and folk cultures [59]. According to The Opinions on Strengthening the Protection and Inheritance of History and Cultural Heritage in the Course of Urban and Rural Construction, the Chinese government specified that the objects of historical culture conservation and inheritance include “historical and cultural cities, towns, villages (traditional villages), blocks, immovable cultural relics, historical buildings, historical areas, as well as industrial heritage, agricultural cultural heritage, irrigation engineering heritage, intangible cultural heritage, and toponymic cultural heritage.” Accordingly, we identified the following nine representative heritage types for conservation: World Cultural Heritage, Globally Important Agricultural Cultural Heritage Systems, World Heritage Irrigation Structures, Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in Rural Areas, China’s Nationally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems, China’s Famous Historical Towns and Villages, China’s Traditional Villages, China’s Ethnic Minority Characteristic Villages, and China’s Nationally Intangible Cultural Heritage in Rural Areas. These typologies comprehensively reflect the diversity of rural culture in Southwest China.

To avoid redundant constraints on the same conservation feature and provide greater flexibility within the SCP software, thereby maximizing the conservation of rural cultural heritage diversity, we implemented a deduplication procedure for the chosen features. In instances where a rural cultural heritage asset falls under several types, it is classified according to the heritage type that has the most stringent conservation measures and selection standards. In our study, world-level cultural heritage sites are accorded with a higher conservation level than national cultural heritage sites. As the pinnacle of cultural preservation and inheritance, World Cultural Heritage necessitates stringent conservation. Tangible cultural heritage requires a greater level of conservation than intangible cultural heritage because of its weaker dissemination capacity, limited coverage, and greater susceptibility to direct impacts from urban–rural construction and natural disasters. For heritage types centered on settlements, China’s Famous Historical Towns and Villages boast the most concentrated historical architecture and the most intact traditional layouts, thereby meriting a higher conservation level. China’s traditional villages include settlements with moderate scales of historical architecture but high degrees of contiguous integrity or distinctive site selection and layout complemented by intangible cultural heritage, resulting in a moderate level of conservation. In contrast, China’s Ethnic Minority Characteristic Villages, which focus more on the unique cultural traits of specific minority groups, have a more limited scope of conservation, resulting in a comparatively lower conservation level. We linked the heritage site to the planning units via the spatial join tool in ArcGIS Pro 3.0.1, to form a spatial database for conservation features. Table 1 presents detailed information on the rural cultural heritage of Southwest China encompassed by planning units. In this study, all heritage data sources were obtained before September 2023. Future studies can use updated data for analysis to better support planning.

Conservation planning approach

We used the SCP software Marxan to delineate conservation networks for rural cultural diversity. The software performs the optimal site-selection process by satisfying preset conservation targets while minimizing conservation costs and considering connectivity, as larger and more compact reserves are normally more effective than scattered reserves [68]. The main operating principle of Marxan is to perform repeated iterative calculations via the simulated annealing process to locate conservation areas that minimize the objective function value. The objective function for Marxan’s analytical planning, which has three parts, is as follows [69, 70]:

(i) The first set of parameters is \(\sum_{{PU}_{s}}Cost\) s, which represents the general costs of the conservation planning units, where s is the number of each planning unit. The direct costs of conservation planning usually include expenses related to construction facilities, management, and community development in conservation areas [71]. However, these costs are often phased, short-term costs [72] that are relatively small and difficult to quantify uniformly across various planning units [73]. Additionally, just as the shrinkage of rural settlements leads to a reduction in cultural diversity and an increase in ecological opportunities, the ecological opportunities sacrificed for cultural diversity conservation represent a cost that is long-term and significant, which warrants considerable attention. Therefore, we characterized ecological opportunity costs, which represent the benefits that people derive from nature, as conservation costs. These costs are expressed in terms of the value of the ecosystem services that can be reasonably quantified by well-established computational methods. They can be viewed as the difference between the current ESV and the ideal ESV. We hypothesize that the ESV between maintaining current land use to preserve rural cultural diversity and the scenario where human activities in the region gradually diminish, ultimately transitioning to an ideal natural state, has a significant gap. This difference represents the ecological opportunity cost of cultural diversity conservation and is expressed as follows:

where \({ESV}_{{PU}_{s} Target}\) represents the ideal ESV for each planning unit and \({ESV}_{{PU}_{s}}\) denotes the current ESV for each planning unit.

The ideal ESV was calculated based on the ESV of the national nature reserves. National nature reserves possess exceptionally high ESV and are more prevalent in areas with minimal human intervention and highly pristine ecological conditions [74]. The macrogeographical context and terrain differences play pivotal roles in influencing the spatial heterogeneity of ESVs at larger scales [75]. Therefore, we utilized the average ESV from national nature reserves (http://www.papc.cn/html/folder/946895-1.htm) in four distinct geographic zones of the southwest region as the ideal ESV for the corresponding planning units within these zones. These zones include the Xizang Plateau, the Sichuan Basin, the Chongqing Hills, and the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau. The current ESV was calculated according to the actual ecosystem type of each planning unit.

We used the equivalency factor method to calculate the ESV, which is adapted to the current ecological conditions in China [76]. For this method, the economic value of each ecosystem service from an ecosystem was estimated as the product of an equivalence coefficient. Moreover, the economic value was represented by one standard equivalence factor, which is the value of the product or service provided per unit area. The equivalence coefficient reflects the relative weight of a certain ecosystem. The standard equivalence factor for ecosystem services was defined as the economic value of the natural grain output from 1 ha of farmland. We calculated a standard equivalence factor of 1645.82 RMB yuan per hectare for the southwest region based on 2018 rice yields (https://www.gov.cn) and unit prices (http://www.gov.cn) for the region. According to land use types, the main ecosystem types in Southwest China include 8 categories—cropland, woodland, grassland, watershed, desert, wetland, construction land, and unused land—that can provide 4 primary ecosystem services and 11 secondary categories [77]. The total ESV was obtained by summing the service values of the different ecosystems. The formula for calculating the total ESV is as follows:

where ESV indicates the ecosystem service value of the planning unit (expressed in RMB yuan), i is the number of ecosystem types, j is the number of ecosystem service types, \({A}_{i}\) is the area of the ecosystem type, \({e}_{ij}\) is the equivalence coefficient of the jth ecosystem service for the ith ecosystem, and V is the economic value expressed as one standard equivalence factor, as described in Xie et al. (2015). The costs of the planning units are provided in Fig. S1.

(ii) The second set of parameters pertains to \(BLM\sum_{{PU}_{s}}Boundary\), which refers to boundary costs and determines the aggregation of the conservation areas. \(\sum_{{PU}_{s}}Boundary\) represents the cumulative boundary length for selecting the conservation areas calculated by the software. The boundary length modifier (BLM) is designed to equilibrate the conservation area boundary length with the associated conservation cost, thereby mitigating potential surges in conservation expenditures caused by overly extended boundaries. Conservation costs and boundary lengths vary across different conservation scenarios. As a result, for each scenario, a different BLM value must be selected. We used the Graph BLM tool in the ArcMarxan toolbox, with increments of 2,500, to determine the optimal BLM value that effectively balances both general costs and boundary lengths (Fig. S2).

(iii) The third set of parameters is \(\sum_{ConValue}SPF\times Penalty\), which represents the total penalty imposed when conservation targets are not met. The penalty indicates the penalty given for not adequately representing conservation features, which is calculated by the conservation costs of the planning units. The species penalty factor (SPF) is a multiplier of different conservation features that determines the penalty size added to the objective function. We started with an SPF value of 0.5 and adjusted it in increments of 0.5. Using the Calibrate SPF tool in the ArcMarxan toolbox, we determined the optimal SPF values for conservation features across various conservation scenarios (Table S1).

We input the aforementioned parameters, along with the quantity of heritage sites in each planning unit and conservation targets for different conservation features, into Marxan software and ran it 100 times, with each run comprising 10 million iterations. Marxan can output two conservation planning results after each run. The “summed solution” file provides the irreplaceability index (0–100) for each planning unit and identifies the importance of the planning unit in reaching conservation targets and assisting in the priority of conservation efforts. The “best run” file denotes the conservation areas with the lowest objective function values and signifies the optimal conservation solution [70].

Setting scenarios and evaluation

The results of conservation planning for cultural diversity are largely determined by the current conservation status, conservation visions, and trade-offs between the values of different rural cultural heritage sites [78, 79]. In previous systematic conservation studies, the establishment of conservation scenarios typically considered the following factors: future development trends [80], conservation targets [81], costs [82], conservation measures [83], trade-offs between various attributes of conservation features (such as themes, values, and levels of endangerment) [84], benefits to stakeholders [44], conditions of planning units (including resource conditions, current conservation levels, and degree of disturbance) [85], and the compactness of conservation areas [86]. Based on these components, we developed four Marxan operating scenarios to address the uncertainties in rural cultural diversity conservation, comprising value-based, existing systems fixed with high and low conservation levels (Table 2). We met the conservation rules for different scenarios by setting conservation targets and either ignoring or retaining existing rural cultural heritage conservation systems.

The conservation targets denote the anticipated proportion of conservation for various types of rural cultural heritage. Considering the challenge in determining quantitative targets for the conservation of rural cultural heritage, we established a range for these targets between 10 and 100%, with increments of 10%. We tested and compared the outcomes of conservation planning at various target levels. In conjunction with expert opinions, we then selected appropriate combinations of conservation targets for different scenarios (Table 3). Furthermore, we ensured that the conservation planning results under the various scenarios were significantly distinct, which makes the outcomes sensitive to each scenario and thereby guarantees the rationality of the scenario setup.

For the value-based and existing systems fixed scenarios, the target weights correspond to the value weights of the heritage site, thereby ensuring that rural cultural heritage sites with higher values are more likely to be prioritized for conservation. Meanwhile, the cultural heritage sites with lower values can be appropriately compromised. The value weights of the heritage site were referenced against the conservation levels defined in the section on conservation feature selection, with greater conservation levels corresponding to higher value weights. We established a strict 100% conservation target for the most valuable World Cultural Heritage site and reduced this target to 90% for other world-level heritages. For China’s Ethnic Minority Characteristic Villages, the target was set at half of that for China’s Traditional Villages. The national-level tangible cultural heritage targets were set 10% lower than those for world-level rural cultural heritage. A minimum target of 10% was set for the least valuable of China’s Nationally Intangible Cultural Heritages.

For the high and low conservation level scenarios, we defined conservation levels based on the conservation proportions of the ideal state for the heritages of all types. The ideal state is when the heritage objects of all types aim for a 100% conservation target without regard for boundary length constraints (BLM = 0) and are subject to the minimal penalty (SPF = 0.5). In this ideal state, the average conservation proportion for heritages of all types stands at 63.09%. In the high conservation level scenario, we set the conservation targets to exceed 60% for all categories, and we raised the target for the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity to 90%. In the low conservation level scenario, we maintained the target levels for world-level heritages as in the first two scenarios. For all other world-level heritage sites, except for World Cultural Heritage sites, we set a target of ≤ 60%. Additionally, we established a minimum target of 10% for national-level heritages to meet the needs of conservation.

To evaluate the influence of the various conservation scenarios on the optimal solutions, we compared the general costs, compactness, quantity, area, and spatial distribution of the optimal solutions across the different scenarios. The method for calculating general costs was introduced in the section on conservation planning approaches.

The compactness ratio (CR) reflects the completeness and clustering degree of the optimal conservation plan for each scenario [87]. When the compactness of the optimal conservation plan is lower, it becomes more dispersed, which reduces the likelihood of maintaining the stability of its internal rural cultural diversity resources [68]. We used the following formula to calculate the CR:

where S is the area of the optimal conservation plan, and the Boundary Length is the perimeter of the optimal conservation solution.

Results

Conservation prioritization

We adopt the irreplaceability index exported by Marxan as a reference to categorize the selected irreplaceable planning units into different levels of priority areas for conservation (Fig. 3). The conservation contribution rate refers to the ratio of the overall number of conserved heritages to the target number, which is indicative of the extent to which the conservation targets have been achieved. Except for the low conservation level scenario, the first priority areas constitute the largest area (Fig. S3) and have the highest conservation contribution (Fig. S4), which play a dominant role in the conservation of rural cultural diversity. We use the value-based scenario as a reference to analyze the conservation priorities of all scenarios.

Under the value-based scenario, 1414 planning units are irreplaceable, with an average irreplaceability index of 61.38. The irreplaceable areas cover an area of 408,500 km2, accounting for 17.68% of the total area. Among these areas, 45.46% are first priority areas, 9.83% are second priority areas, 8.97% are third priority areas, 7.64% are fourth priority areas, and 28.11% are fifth priority areas (Fig. S3). The first priority areas have a conservation contribution rate greater than 1 (Fig. S4) and are located mainly in the following: the Xiangquan River Basin in the Ali Prefecture of western Xizang; the Chongqu River Basin, the Nimu Maqu River Basin, Yalong River Basin and Niyang River Basin in southern Xizang; the Jinsha River-Yalong River Basin, Jinsha-Dingqu River Basin and Litang River Basin in northwestern Sichuan; the Meigu River Basin, Min River Basin, and Tongjiang River Basin around the Sichuan Basin; the Dujiangyan-Tongjiyan irrigation area in the Sichuan Basin; the Yangtze River-Tuojiang River confluence, Wuling Mountain area and Jiannan River Basin in Chongqing; the Anshun area in central Guizhou; the Qingshui River-Duliu River Basin in southeastern Guizhou; the Shiqian River Valley in northern Guizhou; the Hengduan Mountains-Three Parallel Rivers area and Yao’an Bazi area in northwestern Yunnan; and the Liusha River Basin, Ning’er River Valley, Yuan River Valley and Guangnan area in southern Yunnan Province (Fig. 3).

Under the existing systems fixed scenario, 1015 planning units are irreplaceable, with an average irreplaceability index of 77.48. The irreplaceable areas cover an area of 287,300 km2, accounting for 12.44% of the total area. Among these areas, 63.60% are first priority areas, 7.18% are second priority areas, 5.79% are third priority areas, 6.64% are fourth priority areas, and 16.79% are fifth priority areas (Fig. S3). Compared with those in the value-based scenario, the size of each priority area decreases, but the overall irreplaceability increases, especially since the proportion of first-priority areas increases. The conservation contribution rate of the first priority areas is greater than 1 (Fig. S4). This scenario contains additional first priority areas, including the following: the Longxi River Valley and Bahe River Basin in southwestern Sichuan Basin; the Geshiza River-Dajinchuan River Valley and Sidaogou River Valley in the Hengduan Mountains of northwestern Sichuan; and the confluence area of the Yangtze River and Wujiang River in Chongqing (Fig. 3).

Under the high conservation level scenario, 2739 planning units are irreplaceable, with an average irreplaceability index of 74.39. The irreplaceable areas cover an area of 733,400 km2, accounting for 31.74% of the total area. Among these areas, 62.00% are first priority areas, 7.04% are second priority areas, 5.56% are third priority areas, 6.45% are fourth priority areas, and 18.95% are fifth priority areas (Fig. S3). The size of each priority area expands because of elevated conservation targets. The conservation contribution rate of the first priority areas is 0.94 (Fig. S4). Compared with the previous two scenarios, this scenario adds the following areas as first priority areas: the Gar Zangbo River Basin in the Ali Prefecture of western Xizang; the upper Nujiang River Basin in northern central Xizang; the middle and lower reaches of the Yarlung Zangbo River Basin in southern Xizang; the upper reaches of the Lancang River Basin in eastern Xizang; the Dulong River Basin in northwestern Yunnan; the Nanpanjiang River Basin in southwestern Guizhou; the Wujiang River-Liuchong River Basin in western Guizhou; and the Jialing River-Bailong River Basin in northern Sichuan (Fig. 3).

Under the low conservation level scenario, 593 planning units are irreplaceable, with an average irreplaceability index of 39.30. The area of nonreplaceable areas decreases to 151,900 km2, accounting for 6.57% of the total area. Among these areas, 19.53% are first priority areas, 7.13% are second priority areas, 12.98% are third priority areas, 15.22% are fourth priority areas, and 45.14% are fifth priority areas (Fig. S3). The overall irreplaceability of the planning units is reduced because of the lowered conservation targets. The conservation contribution of the first priority areas is 0.69 (Fig. S4). As a result, other priority areas become critical to achieving conservation targets. Therefore, the conservation of rural cultural diversity under this scenario should emphasize the conservation value of planning units with low irreplaceability values. The priority areas show a contraction trend toward the following areas: the middle Yarlung Zangbo River-Yarlung River Valley in southern Xizang; the Jinsha River-Yalong River Basin, Shuoqu River Valley, and Lequ River Valley in northwestern Sichuan; the Dujiangyan-Tongjiyan irrigation area in Sichuan Basin; the Qingshui River Basin and Duliu River Basin in southeastern Guizhou; the Xi’er River Valley in northwestern Yunnan; the Gezan Township of Shangri-La; and the Yuanjiang River Valley in southern Yunnan (Fig. 3).

Optimal solutions

In the optimal conservation plan, the conservation planning units are assembled into conservation areas of different sizes (Fig. 4), which can achieve the conservation targets of all heritage properties (Fig. S5). Under all scenarios, the conservation areas are distributed across the following 15 regions: the Chongqu River Valley, Nimu-Maqu Basin, and middle Yarlung Zangbo River-Yalong River Valley in southern Xizang; the Jinsha River-Yalong River Basin, Jinsha River-Dingqu River Valley and Litang River Basin in northwestern Sichuan; the Jinsha River-Shuoqu River Basin, Erhai Basin, and Mangshi River Valley in northwestern Yunnan; the Yuan River-Tengtiao River Basin in southern Yunnan; the Dujiangyan-Tongjiyan irrigation area in Sichuan Basin; the Min River-Heishui River Basin on the western edge of Sichuan Basin; the Yangtze River-Jiannan River Basin in northeastern Chongqing; and the Qingshui River Basin and Duliu River Basin in southeastern Guizhou. The general costs, compactness of the optimal solutions, numbers and sizes of the conservation areas under each scenario are shown in Table 4.

The value-based scenario contains 32 conservation areas, and each has an average area of 7451.92 km2, adding up to a total area of 245,900 km2 or 10.64% of the study area, and involves county-level administrative divisions. The overall layout of the optimal conservation plan is compact, with a moderate number of medium-sized conservation areas, and features a low general cost.

The existing systems fixed scenario contains 55 priority conservation areas, and each has an average area of 3465.07 km2, totaling 211,400 km2 or 9.15% of the study area, and involves 166 county-level administrative divisions. Although this scenario shares the same conservation targets as the value-based scenario, the compactness and connectivity of the optimal conservation plan under the existing systems fixed scenario are lower because of constraints. Moreover, many of the conservation areas are small and relatively dispersed, which leads to increased costs and discourages centralized management.

The high conservation level scenario contains 59 priority conservation areas, and each has an average area of 8896.63 km2, totaling 524,900 km2 or 22.72% of the research area, and involves 265 county-level administrative regions. To achieve higher targets, the number and size of conservation areas in the optimal conservation plan are greater. However, this scenario leads to decreased compactness, and the overall cost is more than twice as high as that of the value-based scenario. Large-scale continuous rural cultural diversity conservation plans have greater impacts on the natural ecosystems of rural areas and contain more potential conservation conflicts, which, in turn, are not conducive to sustainable cultural development.

The low conservation level scenario contains 34 priority conservation areas, and each has an average area from 3576.01 km2 to 57,200 km2 or 2.48% of the study area, and involves 52 county-level administrative divisions. The optimal conservation plan is the least expensive and most compact and focuses on important world-level rural cultural heritage in low-cost areas. It features the fewest and smallest conservation areas, thereby minimizing conflicts between rural cultural diversity conservation and natural ecosystem conservation.

Conservation networks in the value-based scenario

By comprehensively considering the number of conservation areas, average size of each conservation area, general costs, and compactness of the optimal conservation plan, we concluded that the value-based scenario is most feasible. We thus constructed conservation networks that use this scenario as an example. We wanted to reflect the spatial heterogeneity among the components and the intrinsic mechanism that underlies the differences in cultural diversity resources among different areas. Therefore, we adopted a bottom-up approach to further integrate the conservation areas into larger RCDAs while taking the conservation areas in the optimal conservation plan as CCAs. We comprehensively considered the regional differences in the geographical environment and traditional rural culture. We also referred to previous research results, including the comprehensive regionalization of Chinese human geography [88] and Chinese rural territorial systems [89], among others [90,91,92]. We then proposed rural cultural diversity conservation networks in southwestern China, which feature “9 RCDAs and 33 CCAs” and cover 233 planning units (Fig. 5). Basic information on the conservation networks is provided in Table S2.

Discussion

We proposed a framework for cultural diversity conservation planning as a new approach to enhancing cultural sustainability. Previous studies have typically relied on spatial analysis or value assessment methods to define rural cultural conservation areas. However, these methods are limited in their systematicity and lack a recognition and exploration of the complex relationships between rural cultural conservation and nature conservation [93, 94]. In this study, by employing the SCP approach, we balanced the effectiveness of rural cultural diversity conservation with ecological opportunity costs. For cultural diversity conservation management, this approach can establish cost-effective control mechanisms by setting conservation targets, costs, and boundary lengths, thus meeting various stages of conservation needs. For dynamic cultural diversity monitoring, the efficacy of current rural cultural diversity conservation efforts can be gauged by comparing set conservation targets with the prevailing conservation proportions.

We identified conservation priorities and optimal solutions for preserving rural cultural diversity in Southwest China. Traditionally, systematic conservation research has focused primarily on natural ecological elements and establishing conservation scenarios based on targets, attributes of elements, conditions of planning units, and other factors. However, the research that focuses on cultural diversity conservation planning is limited. Accordingly, we compared the results of rural cultural diversity conservation planning across the four scenarios. In terms of conservation priorities, first priority areas within the value-based, existing systems fixed, and high conservation level scenarios have the highest contribution rates and are of paramount importance. In the low conservation level scenario, the contribution rate of first priority areas diminishes, suggesting the importance of considering the value of conservation areas beyond those of first priority. In optimal solutions, setting overly ambitious conservation targets and strict constraints can compromise other system properties, such as cost efficiency and compactness, in the pursuit of fully meeting conservation feature targets. Therefore, on balance, the value-based scenario is the most feasible. Our results are consistent with the spatial requirements of the World Heritage Convention’s Operational Guidelines, which state that “delineated conservation boundaries should be drawn to include all those areas and attributes (e.g., habitats, species, processes, or phenomena) that are a direct tangible expression of the Outstanding Universal Value of the property [78].” Therefore, the value-based scenario demonstrates broader applicability and reference in the context of cultural heritage conservation and the value assessment of various types of cultural heritage.

Based on the methodology and empirical results presented in this study, we propose a program for conservation networks of rural cultural diversity in Southwest China that includes 9 RCDAs and 33 CCAs. We compare our new conservation networks with conservation systems based on demonstration counties (cities and districts) for the centralized and continuous conservation and utilization of traditional villages and cultural ecological conservation areas (experimental areas). Our new conservation networks align better with the holistic and hierarchically nested features of the human-settlement environment and the connection between rural cultural heritage and the human-settlement environment. It encompasses essential types of rural cultural heritage in the southwestern region and high conservation value areas outside existing conservation systems. It is thus more conducive to achieving the goal of preserving the diversity of rural cultures.

With the SCP approach, our rural cultural diversity conservation areas are more effective. Conservation effectiveness is the proportion of conservation features that are protected by CCAs or existing conservation systems. The existing conservation systems include demonstration counties (cities and districts) for the centralized and continuous conservation and utilization of traditional villages and cultural ecological conservation areas (experimental areas). These areas cover an expanse of 40.50 million km2, representing 17.53% of the region, with an ecological opportunity cost of 39.72 × 1010 (RMB yuan). However, these areas fail to protect certain environments enriched with rural cultural heritage and do not include any World Cultural Heritage or World Heritage Irrigation Structures. We compare the CCAs with the existing conservation system (Fig. 6). Despite a reduction in area of 159,100 square kilometers, CCAs effectively address the conservation gaps in World Cultural Heritage and World Heritage Irrigation Structures. In this way, CCAs significantly contribute to the comprehensive conservation of World Cultural Heritage. There has been a notable increase in the conservation effectiveness of China’s Historic Cultural Towns and Villages and China’s Important Agricultural Cultural Heritage sites. The ecological opportunity cost decreases by 10.46 × 1010 RMB yuan, reflecting a reduction rate of 26.35%. Additionally, the average conservation effectiveness increases from 41.27% to 70.89%, indicating a 29.62-percentage point increase (Fig. 7). Consequently, the new conservation networks are more efficient and sustainable.

Based on the above findings, we recommend the following policy recommendations. (1) At both the national and southwestern regional levels, to safeguard the conservation networks of rural cultural diversity, a conservation mechanism for cross-regional overall conservation and interdepartmental collaborative management should be established. This approach can coordinate and harmonize the development relationships among various RCDAs and devise multiple differentiated conservation strategies. This approach can also optimize the spatial distribution of regional conservation work and promote the formation of regionally characteristic clusters of rural cultural spaces. In this way, the systematic and focused conservation of rural cultural diversity can be ensured. (2) At the level of RCDAs, the conservation of cultural diversity should focus on better coordinating systematization and CCAs. Conservation and planning strategies may include constructing a rural cultural exhibition system centered on CCAs and establishing connections between CCAs through linear infrastructure such as roads and water systems or through cultural migration routes in RCDAs. (3) At the CCA level, rural cultural diversity conservation should leverage the inherent advantages of these areas, notably their high cultural value and low ecological opportunity conservation potential. In this way, concentrated and efficient rural cultural display spaces that also influence neighboring regions will be formed. Here, conservation and planning strategies for cultural diversity focus more on the implementation of spatial control and the demonstration and adaptive use of rural cultural heritage values. For example, for land use, planning authorities can incorporate the boundaries of CCAs into a comprehensive spatial management framework, along with urban development boundaries, permanent basic farmland conservation redlines, and ecological conservation redlines. This strategy will mitigate the influence of urban and rural construction on the spatial pattern of regional rural cultural diversity. For heritage itself, the eco-museum model can be adopted for dynamic in situ conservation. Ultimately, the southwest region can gradually establish a systematic conservation framework for rural cultural diversity by using basic human settlement units as carriers that range from strict conservation at the grassroots level to regional support and safeguarding.

Considering the rationality and feasibility of conservation networks, our study can be further improved in the following aspects. (1) Regarding conservation costs, there is an uneven distribution and geographic variability of national nature reserves within each geographic unit. Therefore, using the average ESV value of national nature reserves in each geographic unit as the benchmark of each planning unit for calculating conservation costs introduces errors. A more refined approach on a smaller scale might yield better accuracy. (2) Moreover, we have not designated a cost threshold penalty; however, in actual planning practice, exact adjustments can be tailored to specific conservation objectives and budgetary limitations. (3) Concerning the setting of conservation scenarios, we can establish more diverse scenarios based on actual conservation needs, associated costs, boundary lengths, or a more accurate value judgment. (4) For heritage selection, parameter settings, conservation network design, and policy development, convening an interdisciplinary team and engaging experts from fields such as ecology, history, sociology, geography, anthropology, architecture, and urban and rural planning are beneficial. This team, in conjunction with local villagers, planners, and policymakers, can enhance the implementation of conservation programs.

Conclusion

Conservation planning for cultural diversity is crucial for safeguarding global cultural sustainability. In this study, we utilized the SCP approach to conduct cultural diversity conservation planning in Southwest China. We addressed the core challenges in cross-regional rural cultural heritage conservation, such as difficulties in integrating cultural heritage with the environment, reconciling the value of different conservation features, and conflicts between conservation costs and benefits. Using Marxan software, we identified priority area solutions and optimal solutions for regional cultural diversity conservation in different scenarios. This exploration led to the construction of cultural diversity conservation networks in rural Southwest China that have ecological and cultural benefits and align with holistic, hierarchical, and local characteristics. The findings provide important references for cultural diversity conservation planning practices, the formulation of conservation policies, and sustainable cultural development in the rural areas of southwestern China.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- SCP:

-

Systematic conservation planning

- ESV:

-

Ecosystem service value

- BLM:

-

Boundary Length Modifier

- SPF:

-

Species Penalty Factor

- CR:

-

Compactness Ratio

- RCDA:

-

Rural cultural diversity area

- CCA:

-

Core conservation area

References

UNESCO. The 2005 Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions. 2005. https://www.unesco.org/creativity/en/2005-convention. Accessed 23 Sep 2023.

Vlami V, Kokkoris IP, Zogaris S, Cartalis C, Kehayias G, Dimopoulos P. Cultural landscapes and attributes of “culturalness” in protected areas: an exploratory assessment in Greece. Sci Total Environ. 2017;595:229–43.

Liu Y, Liu Y, Chen Y, Long H. The process and driving forces of rural hollowing in China under rapid urbanization. J Geogr Sci. 2010;20(6):876–88.

Quintas-Soriano C, Buerkert A, Plieninger T. Effects of land abandonment on nature contributions to people and good quality of life components in the Mediterranean region: a review. Land Use Policy. 2022;116: 106053.

Zhang X, Brandt M, Tong X, Ciais P, Yue Y, Xiao X, et al. A large but transient carbon sink from urbanization and rural depopulation in China. Nat Sustain. 2022;5(4):321–8.

Lin BB, Melbourne-Thomas J, Hopkins M, Dunlop M, Macgregor NA, Merson SD, et al. Holistic climate change adaptation for World Heritage. Nat Sustain. 2023;6(10):1157–65.

Foster G, Saleh R. The circular city and adaptive reuse of cultural heritage index: measuring the investment opportunity in Europe. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2021;175: 105880.

UNESCO. Universal declaration on cultural diversity. 2001. https://en.unesco.org/about-us/legal-affairs/unesco-universal-declaration-cultural-diversity. Accessed 12 Feb 2024.

UNESCO. Convention concerning the protection of the world cultural and natural heritage. 1972. https://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/. Accessed 12 Jun 2023.

Australia ICOMOS. The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance. 2013. https://australia.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Burra-Charter-2013-Adopted-31.10.2013.pdf. Accessed 8 Apr 2023.

Parks Canada. Standards and Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Places in Canada. 2010. https://www.historicplaces.ca/en/pages/standards-normes.aspx. Accessed 12 Jun 2023.

Historic England. Conservation Areas. 2007. https://opendata-historicengland.hub.arcgis.com/maps/historicengland::conservation-areas/explore. Accessed 6 Oct 2023.

Mairie de Suresnes. Site Patrimonial Remarquable (SPR). 2008. https://opendata.hauts-de-seine.fr/explore/dataset/site-patrimonial-remarquable-spr/information/. Accessed 12 Oct 2023.

National Park Service. Discover NHAs - National Heritage Areas. 2023. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/heritageareas/discover-nhas.htm. Accessed 15 Sep 2023.

Ter Ü, Özcan K, Eryiğit S. Cultural heritage conservation in traditional environments: case of Mustafapaşa (Sinasos), Turkry. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2014;140:138–44.

Casson SA, Martin V, Watson A, Stringer A, Kormos CF, Locke H, et al. Wilderness protected areas: management guidelines for IUCN Category 1b protected areas. Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series. 2016(25).

Hoffmann J, Nowakowski A, Metera D. Integrating Natura 2000, rural development and agrienvironmental programmes in Central Europe. Warsaw: International World Conservation Union; 2004.

World Heritage Committee. Revision of the Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. 1992. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000383579.locale=en. Accessed 1 Oct 2023.

ICOMOS. ICOMOS-IFLA Principles Concerning Rural Landscapes as Heritage. 2017. https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/General_Assemblies/19th_Delhi_2017/Working_Documents-First_Batch-August_2017/GA2017_6-3-1_RuralLandscapesPrinciples_EN_final20170730.pdf. Accessed 6 Aug 2023.

Sahle M, Saito O. Mapping and characterizing the Jefoure roads that have cultural heritage values in the Gurage socio-ecological production landscape of Ethiopia. Landsc Urban Plan. 2021;210: 104078.

UNESCO. Recommendation Concerning the Safeguarding of Beauty and Character of Landscapes and Sites. 1962. http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=13067&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html. Accessed 8 May 2023.

ICOMOS. International charter for the conservation and restoration of monuments and sites. 1964. http://www.international.icomos.org/charters/venice_e.pdf. Accessed 11 Aug 2024.

ICOMOS. The Nara Document on Authenticity. 1994. https://www.icomos.org/en/charters-and-texts/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/386-the-nara-document-on-authenticity-1994. Accessed 6 Aug 2023.

Dallimer M, Strange N. Why socio-political borders and boundaries matter in conservation. Trends Ecol Evol. 2015;30(3):132–9.

Feng X, Hu M, Somenahalli S, Bian X, Li M, Zhou Z, et al. A study of spatio-temporal differentiation characteristics and driving factors of Shaanxi Province’s traditional heritage villages. Sustainability. 2023;15:7797.

Chang B, Ding X, Xi J, Zhang R, Lv X. Spatial-temporal distribution pattern and tourism utilization potential of intangible cultural heritage resources in the Yellow River Basin. Sustainability. 2023;15(3):2611.

Nebbia M, Cilio F, Bobomulloev B. Spatial risk assessment and the protection of cultural heritage in southern Tajikistan. J Cult Herit. 2021;49:183–96.

Huang Y, Shen S, Hu W, Li Y, Li G. Construction of cultural heritage tourism corridor for the dissemination of historical culture: a case study of typical mountainous multi-ethnic area in China. Land. 2023;12(1):138.

UNESCO. Managing cultural world heritage. 2013. https://whc.unesco.org/document/125839. Accessed 11 Aug 2024.

Margules CR, Pressey RL. Systematic conservation planning. Nature. 2000;405(6783):243–53.

Ban NC, Bax NJ, Gjerde KM, Devillers R, Dunn DC, Dunstan PK, et al. Systematic conservation planning: a better recipe for managing the high seas for biodiversity conservation and sustainable use. Conserv Lett. 2014;7(1):41–54.

Pressey R, Watts M, Barrett T, Ridges M. The C-plan conservation planning system: Origins, applications, and possible futures. Spatial Conservation Prioritization: Quantitative Methods and Computational Tools. 2009.

Ball IR, Possingham HP. Marxan (V1.8.2): Marine Reserve Design Using Spatially Explicit Annealing. 2000. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=e4bb170af42f3172e971991599fbbb69d092d1bc. Accessed 2 Mar 2023.

Kelley C, Garson J, Aggarwal A, Sarkar S. Place prioritization for biodiversity reserve network design: a comparison of the SITES and ResNet software packages for coverage and efficiency. Divers Distrib. 2002;8(5):297–306.

Fischer DT, Church RL. The SITES reserve selection system: a critical review. Environ Model Assess. 2005;10(3):215–28.

Moilanen A. Landscape Zonation, benefit functions and target-based planning: Unifying reserve selection strategies. Biol Conserv. 2007;134(4):571–9.

Ciarleglio M, Wesley Barnes J, Sarkar S. ConsNet: new software for the selection of conservation area networks with spatial and multi-criteria analyses. Ecography. 2009;32(2):205–9.

Silvestro D, Goria S, Sterner T, Antonelli A. Improving biodiversity protection through artificial intelligence. Nat Sustain. 2022;5(5):415–24.

Campos FS, Lourenço-de-Moraes R, Llorente GA, Solé M. Cost-effective conservation of amphibian ecology and evolution. Sci Adv. 2017;3(6): e1602929.

Huang Z, Qian L, Cao W. Developing a novel approach integrating ecosystem services and biodiversity for identifying priority ecological reserves. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2022;179: 106128.

Yang R, Cao Y, Hou S, Peng Q, Wang X, Wang F, et al. Cost-effective priorities for the expansion of global terrestrial protected areas: setting post-2020 global and national targets. Sci Adv. 2020;6(37): eabc3436.

Zhu L, Hughes AC, Zhao XQ, Zhou LJ, Ma KP, Shen XL, et al. Regional scalable priorities for national biodiversity and carbon conservation planning in Asia. Sci Adv. 2021;7(35): eabe4261.

Vallecillo S, Polce C, Barbosa A, Perpiña Castillo C, Vandecasteele I, Rusch GM, et al. Spatial alternatives for Green Infrastructure planning across the EU: an ecosystem service perspective. Landsc Urban Plan. 2018;174:41–54.

Nguyen NTH, Friess DA, Todd PA, Mazor T, Lovelock CE, Lowe R, et al. Maximising resilience to sea-level rise in urban coastal ecosystems through systematic conservation planning. Landsc Urban Plan. 2022;221: 104374.

Crossman ND, Bryan BA. Systematic landscape restoration using integer programming. Biol Conserv. 2006;128(3):369–83.

Allan JR, Possingham HP, Atkinson SC, Waldron A, Di Marco M, Butchart SHM, et al. The minimum land area requiring conservation attention to safeguard biodiversity. Science. 2022;376(6597):1094–101.

Gordon A, Simondson D, White M, Moilanen A, Bekessy SA. Integrating conservation planning and landuse planning in urban landscapes. Landsc Urban Plan. 2009;91(4):183–94.

Liang J, He X, Zeng G, Zhong M, Gao X, Li X, et al. Integrating priority areas and ecological corridors into national network for conservation planning in China. Sci Total Environ. 2018;626:22–9.

Yao L, Yue B, Pan W, Zhu Z. A framework for identifying multiscenario priorities based on SCP theory to promote the implementation of municipal territorial ecological conservation planning policy in China. Ecol Indic. 2023;155: 111057.

Zeng W, Tang H, Liang X, Hu Z, Yang Z, Guan Q. Using ecological security pattern to identify priority protected areas: a case study in the Wuhan Metropolitan Area. China Ecol Indic. 2023;148: 110121.

Xu J, Ma ET, Tashi D, Fu Y, Lu Z, Melick D. Integrating sacred knowledge for conservation: cultures and landscapes in southwest China. Ecol Soc. 2005. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-01413-100207.

Sun M, Yang R, Li X, Zhang L, Liu Q. Designing a path for the sustainable development of key ecological function zones: a case study of southwest China. Glob Ecol Conserv. 2021;31: e01840.

CEPF (Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund). (2019). Mountains of Southwest China Hotspot. (2019). https://www.cepf.net/sites/default/files/final.china_.southwestchina.ep_.pdf. Accessed 16 May 2023.

Fan X, Xu W, Zang Z, Ouyang Z. Representativeness of China’s protected areas in conserving its diverse terrestrial ecosystems. Ecosyst Health Sustain. 2023;9:0029.

Fischer DT, Alidina HM, Steinback C, Lombana PI, de Arellano R, et al. Chapter 8: ensuring robust analysis. In: Ardron JA, Possingham HP, Klein CJ, editors., et al., Marxan good practices handbook, Version 2. Vancouver: Pacific Marine Analysis and Research Association; 2010. p. 19–20.

Li G, Jiang G, Jiang C, Bai J. Differentiation of spatial morphology of rural settlements from an ethnic cultural perspective on the Northeast Tibetan Plateau, China. Habitat Int. 2018;79:1–9.

Wang F, Gao C. Settlement–river relationship and locality of river-related built environment. Indoor Built Environ. 2020;29(10):1331–5.

Council of Europe. European charter of the architectural heritage. 1975. https://rm.coe.int/090000168092ae41. Accessed 6 Oct 2023.

Chiva I. Une politique pour le patrimoine culturel rural: Ministere de la Cuture et de la Communication. Mission du patrimoine ethnologique; 1994.

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization). Selection Criteria and Action Plan. 2017. https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/giahs_assets/GIAHS_test/04_Become_a_GIAHS/02_Features_and_criteria/Criteria_and_Action_Plan_for_home_page_for_Home_Page_Jan_1_2017.pdf. Accessed 20 May 2023.

ICID (International Commission on Irrigation & Drainage). Register of ICID Heritage Irrigation Structures (HIS). 2012. https://www.icid.org/icid_his1.html. Accessed 14 Nov 2023. https://en.unesco.org/sites/default/files/china_regprotectionhiscities_entof. Accessed 14 Nov 2023.

UNESCO. Basic Texts of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. 2022. https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/2003_Convention_Basic_Texts-_2022_version-EN_.pdf. Accessed 19 Nov 2023.

MOA (Ministry of Agriculture) of the PRC. Notification of Ministry of Agriculture on Exploration of China Nationally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (China-NIAHS). 2012. https://www.cbd.int/financial/micro/china-giahs.pdf. Accessed 2 May 2023.

General Office of the State Council of the PRC. Regulation on Protection of Famous Historical and Cultural Cities, Towns and Villages. 2008.

MOHURD (Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development), MOCT (Ministry of Culture and Tourism), MOF (Ministry of Finance), NCHA (National Cultural Heritage Administration). The Notice on the Survey of Traditional Villages. 2012. http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2012/04/24/content_2121.40.htm. Accessed 19 Nov 2023.

National Ethnic Affairs Commission. Outline of the Plan for the Protection and Development of Ethnic Minority Villages (2011–2015). 2012. https://www.gov.cn/zhuanti/2012-12/10/content_2609632.htm. Accessed 19 Nov 2023.

General Office of the State Council of the PRC. Opinions of the General Office of the State Council on Strengthening the Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Our Country. 2005. https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2005/content_63227.htm. Accessed 20 Nov 2023.

Fischer DT, Church RL. Clustering and compactness in reserve site selection: an extension of the biodiversity management area selection model. For Sci. 2003;49:555–65.

Ball IR, Possingham HP, Watts ME. Marxan and relatives: software for spatial conservation prioritization. In: Moilanen A, Wilson KA, Possingham HP, editors. Spatial conservation prioritization: quantitative methods and computational tools. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. p. 185–95.

Game ET, Grantham HS. Marxan user manual: for Marxan version 1.8.10. St. Lucia, Queensland, Australia: University of Queensland; Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada: Pacific Marine Analysis and Research Association; 2008.

Baeumler AE, Ebbe K, Licciardi G. Conserving the past as a foundation for the future: China-world bank partnership on cultural heritage conservation. In: Urban development series knowledge papers, no. 12. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group. 2011. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/17389. Accessed 22 May 2023.

Le Bouille D, Fargione J, Armsworth PR. Spatiotemporal variation in costs of managing protected areas. Conserv Sci Pract. 2022;4(6): e12697.

Adams VM, Iacona GD, Possingham HP. Weighing the benefits of expanding protected areas versus managing existing ones. Nat Sustain. 2019;2(5):404–11.

Wu J, Gong Y, Wu J. Spatial distribution of nature reserves in China: driving forces in the past and conservation challenges in the future. Land Use Policy. 2018;77:31–42.

Li L, Li Y, Yang L, Liang Y, Zhao W, Chen G. How does topography affect the value of ecosystem services? An empirical study from the Qihe Watershed. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:11958.

Xie GD, Zhang CX, Zhang LM, Chen WH, Li SM. Improvement of the evaluation method for ecosystem service value based on per unit area. Nat Resour J. 2015;30(8):1243–54.

Xie G, Zhang C, Zhen L, Zhang L. Dynamic changes in the value of China’s ecosystem services. Ecosyst Serv. 2017;26:146–54.

UNESCO. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. 2023. https://whc.unesco.org/document/203803. Accessed 24 Sep 2023.

Wijesuriya G, Thompson J, Young C. Managing cultural world heritage: UNESCO; 2013.

Smith A, Schoeman MC, Keith M, Erasmus BFN, Monadjem A, Moilanen A, et al. Synergistic effects of climate and land-use change on representation of African bats in priority conservation areas. Ecol Indic. 2016;69:276–83.

Egoh BN, Reyers B, Rouget M, Richardson DM. Identifying priority areas for ecosystem service management in South African grasslands. J Environ Manag. 2011;92(6):1642–50.

Mehri A, Salmanmahiny A, Momeni DI. Incorporating zoning and socioeconomic costs in planning for bird conservation. J Nat Conserv. 2017;40:77–84.

Bourque K, Schiller A, Loyola Angosto C, McPhail L, Bagnasco W, Ayres A, et al. Balancing agricultural production, groundwater management, and biodiversity goals: a multi-benefit optimization model of agriculture in Kern County, California. Sci Total Environ. 2019;670:865–75.

Eckert I, Brown A, Caron D, Riva F, Pollock LJ. 30×30 biodiversity gains rely on national coordination. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):7113.

Stewart RR, Noyce T, Possingham HP. Opportunity cost of ad hoc marine reserve design decisions: an example from South Australia. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2003;253:25–38.

Vaz AS, Amorim F, Pereira P, Antunes S, Rebelo H, Oliveira NG. Integrating conservation targets and ecosystem services in landscape spatial planning from Portugal. Landsc Urban Plan. 2021;215: 104213.

Batty M. Exploring isovist fields: space and shape in architectural and urban morphology. Environ Plann B Plann Des. 2001;28:123–50.

Fang C, Liu H, Luo K, Xiaohua Y. Process and proposal for comprehensive regionalization of Chinese human geography. J Geogr Sci. 2017;27:1155–68.

Liu YS, Zhou Y, Li YH. Rural regional system and rural revitalization strategy in China. Acta Geogr Sin. 2019;74(12):2511–28 (in Chinese).

Liu P, Liu C, Deng Y, Shen X, Li B, Hu Z. Landscape division of traditional settlement and effect elements of landscape gene in China. Acta Geogr Sin. 2010;65(12):1496–506 (in Chinese).

Wu B. Partition and the formation of the Chinese culture areas. Acad Monthly. 1996;03:10–5 (in Chinese).

Yang B, Chao H, Li G, He Y. Concept, identification and division of village and town settlements in China. Econ Geogr. 2021;41(05):165–75 (in Chinese).

Bryan BA, Crossman ND. Systematic regional planning for multiple objective natural resource management. J Environ Manage. 2008;88(4):1175–89.

Richards J, Orr SA, Viles H. Reconceptualising the relationships between heritage and environment within an Earth System Science framework. J Cult Herit Manag Sustain Dev. 2020;10(2):122–9.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (2020YFD1100705).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Collecting the data: H. Li, M. Gao Analyzing: H. Li Interpreting the results: H. Li Methodology: Z. Zhou, H. Li Supervision: Y. Zhang, Z. Zhou Writing—original draft: H. Li Writing—review and editing: Z. Zhou, Y. Zhang, H. Li, M. Gao.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Manuscripts reporting studies not involve human participants, human data or human tissue.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, H., Gao, M., Zhang, Y. et al. Mapping cultural diversity conservation networks to enhance cultural sustainability in rural Southwest China. Herit Sci 12, 424 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01503-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01503-y