Abstract

Clay sealing represents the key physical example of the document sealing system of the Qin dynasty in ancient China. However, only the inscriptions and aesthetic values of clay sealings have been discussed until now, and the relevant sources have not been traced from the perspective of scientific analysis. A total of 81 clay sealings unearthed in Xi’an were studied via ultra-depth field microscopy, petrographic microstructure analysis and X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy. The relevant methods of tracing and making clay samples are discussed based on the results of the literature investigation and elemental analysis. The composition, technology and spatial links between different clay sealings collected from all over the country show that highly organized sealing materials and systematic processes are important parts of the establishment of unified China. They also provide detailed and effective scientific information that is useful for the future preservation of clay sealings protection and further archaeological research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The clay sealing is an antique used for the encapsulation of documents, which was put on Jian (wooden board) that bounded with a cord in the Qin and Han dynasties. Then the clay would be employed on the Jian in order to seal the entire set of documents impressed by an official seal. And it facilitated the safe delivery of documents. The earliest clay sealing in Chinese history can be traced back to the Warring States period and was widely used in the Qin and Han dynasties [1]. Moreover, the traces of retained on the back of most clay sealing samples provide important information for the discussion of the sealing system of Qin documents, confirming and complementing the research of Qin officials based on documents. In the second half of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, a comprehensive catalogue of clay sealings was published, among which the main ones were Tieyunzang Clay Sealings, a Summary of Clay Sealings, and a Summary of Clay Sealings collected by Cezhaishou [2]. Most ancient clay sealing samples discovered since the 1950s can be found in archaeological briefs [3] and reports [4, 5]. Ancient Chinese Seals by Sun summarized all kinds of clay-sealed materials unearthed or collected worldwide and clearly presented the evolution of the characters and forms of ancient Chinese seals, as well as the system of counties, officials and official seals in the Qin and Han dynasties. In 2000, Zhou focused on the interpretation of Qin clay sealings unearthed in Shaanxi and their historical value focusing on topics such as production technology and geography. However, the unearthed locations of the clay sealings recorded in these works are scattered. Furthermore, most of the studies focus only on the exploration of the artistic and aesthetic value of the inscriptions and lack relevant, comprehensive, and systematic scientific analysis, and further archaeological discussion [1]. In recent years, many clay sealing samples have been excavated, but no further scientific analysis has been performed.

In this preliminary study, unpublished information on clay sealings unearthed from the same site in Xi’an is presented, and the number and region of clay sealings used in different parts of China are summarized and displayed (Fig. 1). The largest quantity of clay sealings was used in Shaanxi. Additional clay was unearthed in the neighbouring provinces of Shaanxi, such as Sichuan, Henan, Anhui and Shanxi, and this discovery suggests that there may be a potential connection between the production of clay sealings and the geographical location of Shaanxi.

A total of 81 clay sealings samples were selected in this study, all of which were unearthed in Xi’an. Provenance determination of ceramics is often accomplished through combined chemical and petrographic analysis [6, 7]. In this study, ultra-depth field microscopy, thin section ceramic petrography and X-ray fluorescence spectrometry were used to conduct a comprehensive analysis of the selected samples from multiple perspectives (microscopic, phase composition and raw material procurement) and provide detailed scientific information that is useful for their preservation and for further archaeological research.

Research aim

Research on the origin of ceramics (pottery [8,9,10], clay figurines [11]), glass [12], and other cultural relic samples [13] has been effective, but it usually concerns only a specific area. With respect to clay sealings, this research studies the origin of cultural relic samples, which are widely used but not limited to a certain region, to discuss centralization systems. Currently, there is a paucity of scientific and technical analyses of the clay sealing samples unearthed extensively in recent years. This research offers a scientific foundation for further investigation and analysis of clay sealings. Furthermore, the elemental composition and micro-morphology of the samples were examined with the objective to trace the origin of the raw materials used and further discussing the degree of centralisation during the Qin dynasty.

Materials and methods

Sample selection

A considerable number of seals with different styles and characters and whose inscriptions are either legible or not, were excavated at a site in Xi 'an. Eighty-one representative samples were selected for this study. The descriptions of 44 clay sealing samples are shown below (Table 1).

Analytical procedures

OM analysis

The microscopic morphology was observed via an ultra-depth 3D digital microscope (Carl Zeiss Smartzoom5 from Germany). An integrated segmented LED ring light was used to replace the traditional polarizing filter, and the colour, impurities (plant fibre carbonization marks), and surface details of the front and reverse side of each seal were studied.

Petrographic microstructure analysis

The analysis was conducted using two polarizing microscopes, one for observation (Leica DMLSP) and another for sample preparation (Batuo), a polishing machine (Struers Dap-v), a cutting machine (Micro Gut3), a thin section preparation and polishing system (Buehler PretroThin), and a vacuum impregnation apparatus (Germany ATM Brilliant210). The samples were prepared into thin sections of approximately 30 μm thickness and then we use the digital petrography system of PETROG to determine the type and size of 200 evenly distributed small selection areas in the field of 20mm*30mm polarizing microscope.

X-ray fluorescence spectrometry

A micro-X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (German Bruker ARTAX400) was used. The test conditions of the instrument were a voltage of 30 kV, current of 900 μA, helium atmosphere and data acquisition time of 200 s.

Results and discussion

Micromorphology

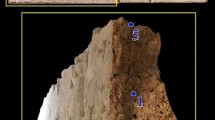

In this study, 81 samples were subjected to micro-observation on their surfaces using ultra-depth of field microscopy. 9 photographs of inscriptions, rope marks and indentations displaying the most obvious and representative marks were selected for display. Figure 2a, b and c show the inscriptions on the surface of the sample, while Fig. 2d, e and f show the impressions of the bamboo slips (processed bamboo strips) retained on the reverse side of the seal during production. These impressions are smooth, the marks of the bamboo strips are oriented in the same direction, and there are two types: interleaving impressions and parallel impressions. Figure 2g, h and j show the seal marks of suspected rope strips. The clay sealings exhibit transverse holes in the central region, with the upper and lower layers displaying partial or complete breakage. The fracture surface is characterised by a neat and smooth appearance, and the holes are fully exposed, with spiral and parallel lines distinctly visible on the sidewalls.

The bamboo strips and rope marks are obvious, but no traces of organic matter have been observed. Only a small number of bamboo slips from the Qin and Han dynasties exist now, and the traces retained on the reverse side of the clay sealing can provide important information, combined with the interpretation of the inscriptions, to further explore archaeological questions.

Petrography

The clay samples bear inscriptions of considerable historical value. but thin section petrography provides important information regarding the clay raw materials used. Therefore, three samples exhibiting the least historical value were selected for petrographic analysis. Petrographic observations revealed that the particle sizes can be divided into two trends below: a) 0.06 mm and between 0.174 mm and 1.313 mm (the particles below 0.029mm are more uniform), and b) below 0.025mm and between 0.039 mm and 0.163 mm. Most of the particles are angular with different sizes. The colour of the matrix both in PPL and XPL is dark yellowish-brown. The voids are elongated, accounting for 46.3%, 63% and 68.7%, respectively, and the yellowish-brown material is elliptical (Table. 2; Fig. 3, 4, 5).

The percentage of the voids in the thin sections of the samples is greater than 7% and less than 10%. The proportion of the matrix is approximately 46% to 69%. The proportions of particles in Sample 81–3-2 and Sample 81-3-3 are also relatively close, between 24 and 27%, and the proportion of particles in Sample 81-3-1 is 43.3%. After examination, the main components are quartz and feldspar, and the matrix is more uniform [14, 15]. The difference in the surface colour of the clay sealings is speculated to be caused by the change in the atmosphere during firing. The petrologic characteristics of all the sealed clay samples are mainly quartz and feldspar, which are components of typical sedimentary loess found in northern China [16].

The grain size range is mainly distributed in two trends, forming a bimodal grain size distribution [17], which is in the range of silt particles and gravel (≥ 0.0625 mm), and the grain sizes are very different, which is not consistent with that of natural clay without refining. The presence of inclusions with polymodal or skewed unimodal grain size distributions as a criterion for interpreting intentional clay mixing, given that unprocessed naturally occurring clay is commonly unimodal. Furthermore, significant variations in the composition of inclusions within a single fabric could be attributed to the deliberate blending of multiple clay sources from distinct geological origins [18].

Due to technical limitations, the number of samples currently used in the experiment is small, so we can reasonably speculate that the raw materials of the selected clay sealing samples should be processed and mixed artificially.

X-ray fluorescence spectrometry

An X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis was conducted on all 81 samples collected. The data were converted into the percentage content of oxides corresponding to the elements and recalculated to 100 wt%. Six elements, namely Mg, Al, Si, P, Ca and Fe which exhibited a high degree of dispersion, were selected for principal component analysis and clustering. The specific data are presented in the appendix. The SiO2 content is 70.20%-42.09%, the Al2O3 content is 15.54%-6.47%, and the Fe2O3 content is 7.57%-4.50% (Fig. 6).

There are many similarities in elemental composition, particularly in terms of major elements (aluminium, calcium, and iron), as well as sodium and magnesium. Without excluding the effect of environmental factors related to the burial environment [19], the samples selected for the experiment have relatively consistent elemental composition [20]. Within the PCA analysis, the cumulative contribution rates of the first three principal components are 43.045%, 62.024% and 80.196% (Fig. 7).

Scatter plot clustering was performed with principal components 1 and 2 and principal components 1 and 3, and the results are as follows:

The scatter plots show dense clouds. The results of scatterplots Figs. 8 and 9, which are based on the kernel density estimation method, are clustered nearly in the same central region. Except for the occasional offset of a point in a county far from the central coast, Qin clay sealings are very stable in terms of elemental composition, showing a high degree of consistency and standardization [21] and indicating that the sources of the raw materials may be consistent. However, the use of the clay sealings may not be local to the raw material source. That is, the samples used for research may have raw materials from the same region even if the inscriptions indicate that they are used in different regions. Clay is collected in a centralized organization, processed by specialized technology and distributed to different areas for use [22,23,24], which is an important link in the establishment of a unified China [25].

The Qin dynasty gradually extended its control over the country from north to south, as evidenced by the increasing number of areas represented in the excavated clay sealings. The most significant accomplishment of the Qin dynasty was the establishment of a centralized and highly effective system of governance in 221 BC. The proven effective administrative system for the Qin State served as the foundation for the subsequent Qin Empire government system. The Qin Empire was subdivided into thirty-six chun, or commanderies. Each chun was jointly governed by a chun-shou (administrator), who was responsible for civil affairs, and a chun-wei (military governor), who was responsible for security affairs. The aforementioned achievements are contingent upon the existence of an authentication system [26]. In ancient China, official seals served the function of certifying the authenticity of orders issued by representatives of the court to citizens outside of the overlord's court. Seals were bestowed upon officials at the time of their appointment to their respective posts. Consequently, the composition and materials of these seals vary considerably, and clay sealings were also used prudently.

Conclusion

In this study, the material source of Qin seal mud extracted from the Xi’an site was studied via microscopic observation and elemental analysis.

The microscopic observations revealed no residual organic components in the clay. However, ultra-depth field microscopic observations revealed obvious upper and lower layers inside the clay, with spiral and long string marks visible in the middle that may provide strong support for subsequent research on the bundling method of bamboo slips. In addition, it is presumed that following the application of a high-temperature fire treatment, the document sealed will remain intact and secure during transportation.

Most seals were unearthed in Shaanxi, and more were unearthed in the surrounding provinces of Shaanxi, such as Sichuan, Henan, Anhui and Shanxi. Combined with the results of the principal component analysis, after the first unification of the Qin dynasty, it seems probable that the sealing materials used in the slips and in the document exchanges between the central government and the official offices and officials of the counties were artificially and specially processed that it may have something to do with central government. Therefore, owing to the transportation cost, the amount of regional clay materials near Shaanxi Province must have been large; notably, only a small amount of clay sealings has been unearthed in remote areas. This reflects the strengthening of power of the State of Qin, the exchange of materials and information sharing between the local and central authorities became more frequent and close, and unified collection, processing and distribution revealed that the Qin dynasty strictly controlled official documents. Although the manufacturing of clay sealings could have been carried out locally and information could have been transmitted more quickly and conveniently, the distribution of raw materials was controlled by the central government. This system further reflects the strengthening of the centralization of the Qin dynasty and was inherited by later emperors. The manufacturing technology and administrative management methods demonstrated by this system became a model for the central government in later generations.

The formation of centralized rule laid an extremely important foundation for the current administrative division and the formation of Chinese national culture. As the direct material remains of the sealing system in this historical period, the integration of clay and bamboo slips represents a significant area of interest for the advancement of archaeological and historical research. However, research on the origin and production process of clay sealings is in the initial stage, and research on the physical and chemical properties of other types of cultural relics is not thorough. Although sealing system has not been recorded in texts, the study of the current scientific research could provide valuable information for understanding the formation of the sealing system, which will have profound significance for the development of archaeology and related disciplines.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Zhou X, Liu R, Li K, Tang C. Message recently presented in Beijing showing the ancient Central Official’s Positions as found in the Clay Seal of Qin dynasty - In memory of the 10th anniversary of Qin clay seal of Xiangjia lane. Archaeol Cult relic. 2005;5:3–15. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-7830.2005.05.001.

Liu Q, Li S. A study of the Qin clay sealings from the Xiangjiaxiang site Xi’an. Acta Archaeologica Sinca. 2001;4:1.

Han G, Zhou Z, Chai Y, Zhang X. Summary of Qin clay sealings unearthed at H4 site of Xiangjiaxiang, Xi’an. Wenwu. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1361/j.cnki.cn11-1532/k.2022.10.006.

Chai Y, Zhang X, Zhou Z, Han G. Brief report on the excavation of midden pit no. 30 (H30) at the Xiangjiaxiang Site in Weiyang District, Xi’an City. Archaeology. 2023;3:44–63.

Han B, Cheng L, Ni Z, Zhang X, Wen X, Chai Y, Han G. Preliminary report on the excavation of the ash pit no H3 at the Xiangjiaxiang Site in Xi’an. Wenbo. 2024;2:3–23.

Degryse P, Braekmans D. Elemental and isotopic analysis of ancient ceramics and glass. In: Treatise Geochem. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2013.

Quinn P. Scientific preparations of archaeological ceramics status, value and long term future. J Archaeol Sci. 2018;91:43–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2018.01.001.

Kelepeshi C, Braekmans D, Daems D, Poblome J, Vassilieva E, Degryse P. From Hellenistic slipped tableware to Roman Imperial Sagalassos Red Slip Ware: a petrographic and geochemical study. J Archaeol Sci. 2024;53: 104390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2024.104390.

Quinn P, Zhang S, Xia Y, Xia Y, Li X. Building the Terracotta Army: ceramic craft technology and organisation of production at Qin Shihuang’s mausoleum complex. Antiquity. 2017;91(358):966–79. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2017.126.

Ting C, Erhardt S, Gyulamiryan H, Lichtenberger A, Muradyan S, Schreiber T, Zaradaryan M. The Artaxiad capital of ceramic: Exploring the changing local pottery production and exchange at Artaxata (Armenia) from the 2nd century BCE to 1st century CE. Archaeol Res Asia. 2023;34: 100444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ara.2023.100444.

Braekmans D, Boschloos V, Hameeuw H, Perre A. Tracing the provenance of unfired ancient Egyptian clay figurines from Saqqara through non-destructive X-ray fluorescence spectrometry. Microchemical J. 2019;145:1207–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2018.12.029.

Li J, Sun F, Zhang Y, Ha W, Yan H, Zhai C. Scientific analysis of two compound eye beads unearthed in Hejia Village. Zhouling Herit Sci. 2024;12:127–36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01242-0.

Riehle K, Kistler E, Ohlinger B, Sterba J, Mommsen H. Mirroring Mediterraneanization: pottery production at Archaic Monte Iato, Western Sicily (6th to 5th century BCE). J Archaeol Sci. 2023;51: 104111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2023.104111.

Li X, Yu W, Lan D, Zhao J, Huang J, Xi N, et al. Analysis of newly discovered substances on the vulnerable Emperor Qin Shihuang’s Terracotta Army figures. Herit Sci. 2022;10:72–84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-022-00701-w.

Ho J, Quinn P. Intentional clay-mixing in the production of traditional and ancient ceramics and its identification in thin section. J Archaeol Sci. 2021;37: 102945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2021.102945.

He X, Wen J, He Z, Go I, Liu N, Guo H. Exploring pottery origin by composition and technique comparison: a case study at the Daqu burial site, Beijing China. Herit Sci. 2024;12:126–36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01245-x.

Neyt B, Braekmans D, Poblome J, Elsen J, Waelkens M, Degryse P. Long-term clay raw material selection and use in the region of Classical/Hellenistic to Early Byzantine Sagalassos (SW Turkey). J Archaeol Sci. 2012;39(5):1296–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2012.01.005.

Quinn P. Ceramic petrography: the interpretation of archaeological pottery & related artefacts in thin section. 1st ed. Oxford: Archaeopress; 2013.

Martinón-Torres M, Li X, Xia Y, Benzonelli A, Bevan A, Ma S, et al. Surface chromium on Terracotta Army bronze weapons is neither an ancient anti-rust treatment nor the reason for their good preservation. Sci Rep. 2019;9:5289–300. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-40613-7.

Kracht E, Bloch L, Keegan W. Production of greater antillean pottery and its exchange to the Lucayan islands: a compositional study. J Archaeol Sci. 2022;43: 103469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2022.103469.

Cheng W, Mason R, Shen C. A new approach in petrographic analysis of Loessic ceramics: Late Shang and Western Zhou bronze casting moulds. Archaeol Res Asia. 2023;35: 100449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ara.2023.100449.

Chen D, Yang Y, Jiang T, Yang B, Tang B, Luo W. On coinage technology features and lead material management of the Qin state from the Chengdu Ban Liang coins. J Archaeol Sci. 2021;35: 102779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2020.102779.

Quinn P, Yang Y, Xia Y, Li X, Ma S, Zhang S, Wilke D. Geochemical evidence for the manufacture, logistics and supply-chain management of Emperor Qin Shihuang’s Terracotta Army, China. Archaeometry. 2020;43(1):40–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/arcm.12613.

Marghussian A, Coningham R, Nashli H. The development of pottery production, specialisation and standardisation in the late Neolithic and transitional chalcolithic periods in the central plateau of Iran. Archaeol Res Asia. 2021;28: 100325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ara.2021.100325.

Ao J, Li W, Ji S, Chen S. Maritime silk road heritage: quantitative typological analysis of qing dynasty export porcelain bowls from Guangzhou from the perspective of social factors. Herit Sci. 2023;11:263–82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-023-01103-2.

Mayhew G. The formation of the qin dynasty: a socio-technical system of systems. Procedia Comput Sci. 2012;8:402–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2012.01.079.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff working at Xi’an site and the Emperor Qin Shihuang's Mausoleum Site Museum. They all gave us access to their facilities and waited patiently for us to finish our observations and sampling.

Funding

This research was supported by the 111 project (Grant No. D18004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by LY and HG, and LY provided the samples. The first draft of the manuscript was written by HG, and both authors read and revised the previous versions of the manuscript. Both authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, H., Yang, L. First scientific research to trace the origins of Qin clay sealings. Herit Sci 12, 428 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01524-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01524-7