Abstract

The Angkor monument is a group of temples built between the 9th and 15th centuries. Mahendraparvata, the first capital of the Angkor Empire, was built by King Jayavarman II on the summit of Kulen Mountain, ~35 km northeast of Siem Reap, Cambodia. In this study, we investigated the building materials of the 18 temples that make up Mahendraparvata and found that mainly bricks were used in the construction of temples in Mahendraparvata. Gray sandstone, derived from the Phu Kradung Formation (the Red Terrain Formation) of the late Jurassic to early Cretaceous age (distributed in the southeastern foothills of Kulen Mountain and widely used throughout the Angkor monument), was used in small quantities at the door frames, stairs, and lintels of the temples. Chemical composition measured with a portable X-ray fluorescence analyzer and magnetic susceptibility measured with a portable magnetic susceptibility meter were conducted on the brick and sandstone materials, and the thickness of the bricks was also measured. On the basis of the magnetic susceptibility and Rb content of the bricks, the 18 investigated temples were categorized into three groups: Groups A, B, and C. The Rb content of the gray sandstone revealed that Group A differs from Groups B and C. Temples in Group A, namely Prasat O Phaong, Prasat Khmum, and Prasat Kraham (I & II), are aligned in a straight line, and Prasat O Phaong, Prasat Rong Chen, and Prasat O Top are also aligned in a straight line. The intersection of these two lines is at Prasat O Phaong. This suggests a possible relationship among the temples in Group A. Temples in Group A tend to be in better condition than those in other groups. The thickness of the bricks used in the temples of Mahendraparvata is between the thickness of bricks used in the Sambor Prei Kuk monument from the pre-Angkorian period and those of the temples of Hariharalaya, the next capital after Mahendraparvata. During these periods, there was an overall trend of decreasing brick thickness over time, suggesting a technical connection among these monuments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Angkor monument was built between the 9th to 15th centuries. The first capital of the Angkor Empire, Mahendraparvata, was established in 802 CE by King Jayavarman II on the summit of Kulen Mountain (Phnom Kulen). Kulen Mountain, located ~35 km northeast of Siem Reap—the base for Angkor archaeological tourism—features a flat-topped mountain. Kulen Mountain is the source of the Siem Reap River, which became essential for the Angkor Empire that flourished in the plains to the southwest of Kulen Mountain during the main Angkor period from the late 9th to 15th centuries. Extensive canals and waterways were constructed to effectively use the waters of the Siem Reap River, which became indispensable for agriculture and daily life1. The presence of the Siem Reap River is said to have brought prosperity to the Angkor Empire in the Angkor area. In this sense, the Siem Reap River is considered a sacred river, and many lingas (Hindu symbols), are carved into the riverbed at Kulen Mountain. Along with its natural abundance, Kulen Mountain has also become a resort area for Cambodians.

The city of Mahendraparvata was primarily constructed in the southern area of Kulen Mountain2,3,4. Recent LiDAR surveys have revealed the full extent of the urban networks of Mahendraparvata, which was built during the early period of the Angkor Empire1,3,4,5,6,7. The city featured well-developed roads oriented along east-west and north-south axes, and dams were also built, indicating the practice of water management. In 889 CE, King Yasovarman I moved the capital to Hariharalaya, which is located at the Roluos monument, and in 944 CE, the capital was moved again to the present-day Angkor area by King Rajendravarman II. Many brick temples were constructed at Mahendraparvata, and these are now sites of active research. The temples of Mahendraparvata, like the temples of the Sambor Prei Kuk monument built during the pre-Angkorian period, are primarily made of brick, with sandstone used for the door frames, stairs, lintels, and terraces. In this study, we analyzed the chemical composition of the brick and sandstone materials used in 18 major temples at Mahendraparvata using a portable X-ray fluorescence analyzer and measured magnetic susceptibility using a portable magnetic susceptibility meter. We also measured the thickness of the bricks. Using these data, we interpreted the grouping and construction sequence of the 18 investigated temples. Furthermore, we compared the brick thickness between the pre-Angkorian temples (e.g., the Sambor Prei Kuk monument) and the Angkorian period brick temples, including those at Mahendraparvata. The results revealed systematic changes among these monuments.

Non-destructive methods of measuring magnetic susceptibility using a portable magnetic susceptibility meter and chemical composition using a portable X-ray fluorescence analyzer are highly effective for elucidating the construction order and periods of temples at Khmer monuments, including the Angkor monument8,9,10,11,12. Therefore, in this study, we conducted these investigations, including measuring the thickness of bricks, at the temples of Mahendraparvata on the summit of Kulen Mountain to estimate the construction order of the temples and clarify the types and sources of the sandstone materials used in the temples.

Methods

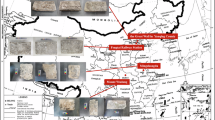

The survey was conducted at the following 18 temples: Prasat Kraham I, Prasat Kraham II, Prasat Khla Khmum, Prasat Anlong Thom, Prasat Neak Ta, Prasat Chrei, Prasat Bos Neak, Prasat O Top, Prasat Damrei Krap, Prasat Bram, Prasat Koki, Prasat Rong Chen, Prasat O Phaong, Prasat Phnom Sruoch, Prasat Khting Slap, Prasat Kancha, Prasat Thma Dap, and Prasat Chup Crei (Fig. 1). The latitude, longitude, and altitude of each temple were measured using a GPS device (eTrex Venture, Garmin Ltd, Schaffhausen, Switzerland) (Table 1). The distribution map of these investigated temples is shown in Fig. 2.

a Prasat Kraham I, b Prasat Kraham II, c Prasat Khla Khmum, d Prasat, Anlong Thom, e Prasat Neak Ta, f Prasat Chrei, g Prasat Bos Neak, h Prasat O Top, i Prasat Damrei Krap, j Prasat Bram, k Prasat Koki, l Prasat Rong Chen, m Prasat O Phaong, n Prasat Phnom Sruoch, o Prasat Khting Slap, p Prasat Kancha, q Prasat Thma Dap, and r Prasat Chup Crei.

The temples surveyed are located in the southeastern part of Kulen Mountain. The temples Prasat O Phaong, Prasat Khla Khmum, and Prasat Kraham (I & II), along with Prasat O Phaong, Prasat Rong Chen, and Prasat O Top, all in Group A, are positioned along two different straight lines, with Prasat O Phaong situated at the point where the two lines intersect. Prasat Damrei Krap is classified in Group B but is situated along the extended line connecting Prasat Kraham (I & II) and Prasat O Top. After the temple names, (A), (B), and (C) indicate their groups based on the chemical composition (Rb) and magnetic susceptibility of the bricks.

Chemical composition analysis of the brick and sandstone materials was performed non-destructively and on-site using a portable X-ray fluorescence analyzer (Delta Premium DP-4000-C, Innov-X Systems Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Rhodium (Rh) was used as the X-ray tube target, with a tube voltage of 15 kV for light elements and 40 kV for heavy elements. The beam diameter of the X-ray is ~10 mm. The measurements were conducted using the “Soil mode,” with a measurement duration of ~1 min. The X-ray fluorescence analyzer is powered by a lithium-ion battery, with a single battery providing ~4 h of measurement time. Prior to the measurements, the calibration curves were created using ten Japanese igneous rock standard samples (JA-1, JA-2, JB-1b, JB-2, JB-3, JG-1a, JG-2, JGb-1, JR-1, and JR-2)13, and the measurement results were corrected accordingly. Each time the equipment was turned on, it was standardized using stainless steel 316SS. Measurements were taken on smooth surfaces without algae or lichen, and surfaces were cleaned with a toothbrush. Measurements were conducted on five samples of brick and sandstone materials, respectively, from each temple, and the average values of the five measurements for brick and sandstone materials, respectively, were calculated for each temple. Please refer to Potts and West14, Mendoza Cuevas et al.15, and Tykot16 for details regarding the portable X-ray fluorescence analyzer.

Magnetic susceptibility measurements of the brick and sandstone materials were conducted using a portable magnetic susceptibility meter (SM30, ZH Instruments, Brno, Czech Republic). The measurements were performed non-destructively and on-site. The measurement coil had a diameter of 5 cm. Magnetic susceptibility was measured on the surface of the brick or sandstone materials (smooth surfaces without algae or lichen) and then in the air (Mode A). The measurement time for each location was ~2–3 s and the measurement accuracy was ~0.001 × 10–³ SI units. From each temple site, 25 samples of brick and 5 samples of sandstone were measured, and the average values for each material at each temple were calculated. For details on the magnetic susceptibility measurements and their effectiveness, refer to William-Thorp and Thorp17, William-Thorp et al.18,19, Alva-Valdivia et al.20. and Tanikawa et al.21.

The thickness of the bricks was usually measured on wall surfaces: the thickness of 10 rows of bricks was measured at 5 locations (a total of 50 bricks) and the thickness per individual brick was calculated. In cases where the temple had collapsed and the wall surfaces were no longer intact, the thicknesses of 50 scattered bricks were measured and the average value calculated (Prasat Rong Chen).

Results

Bricks

Chemical composition

The analytical results for the representative elements detected in the bricks using the portable X-ray fluorescence analyzer are shown in Table 2 (please refer to Additional File 1 for detailed chemical analysis data). Among these data, Rb was the only element that exhibited significant differences between the temples, with average values for each temple ranging from 5 to 110 ppm.

Magnetic susceptibility

The magnetic susceptibilities of the bricks measured with the portable magnetic susceptibility meter are shown in Additional file 2. There was a considerable range in the average magnetic susceptibility values for each temple, ranging from 0.05 × 10–³ to 5.6 × 10–³ SI units.

Thickness of bricks

The thicknesses of the bricks for each temple are shown in Additional file 3. The relationship between the average Ti content and average thickness of the bricks used in the temples surveyed is shown in Fig. 3. For comparison, the relationship between the average Ti content and average thickness of the brick sanctuaries from the Sambor Prei Kuk Monument, which was built during the pre-Angkor period, is also drawn in Fig. 3. The range of average brick thickness values for each temple is 50 to 60 mm, and that of average Ti content values is 1800 to 4400 ppm. No significant systematic differences were observed among the surveyed temples (Fig. 3). However, based on data from the sanctuaries of the Sambor Prei Kuk Monument, each temple in Mahendraparvata tends to have been constructed at a later period than the Sambor Prei Kuk sanctuaries. This observation aligns with the construction periods of both sites.

As a comparison, the thickness and Ti content of the bricks used in the pre-Angkorian Sambor Prei Kuk Monument are found within the region enclosed by the brown line25.

Sandstone blocks

Chemical compositions

The analytical results for the representative elements detected in the chemical composition analysis using the portable X-ray fluorescence analyzer are shown in Table 3 (please refer to Additional File 4 for detailed chemical analysis data). The average Sr content of the gray sandstone at each temple ranged from 150 to 200 ppm, while the average Rb content ranged from 60 to 140 ppm. In white or red sandstones, the Sr and Rb contents were below 26 ppm and 12 ppm, respectively, suggesting these materials are siliceous sandstones (Additional File 4)22,23. Although only present in small quantities, siliceous sandstone was identified only in Prasat Bos Neak, Prasat Koki, Prasat O Top, and Prasat Rong Chen.

Magnetic susceptibility

The magnetic susceptibility measurements for the sandstone used in each temple, obtained using a portable magnetic susceptibility meter, are shown in Additional file 5. The average magnetic susceptibility of the gray sandstone in each temple ranged from 1 × 10–³ to 5 × 10–³ SI units. However, in Prasat Bos Neak, Prasat Koki, Prasat O Top, and Prasat Rong Chen, some sandstones had magnetic susceptibilities below 0.025 × 10–³ SI units and are siliceous sandstones because of their low magnetic susceptibility22,23.

Discussion

Grouping of temples based on brick and sandstone materials

Based on the plot of average magnetic susceptibility versus average Rb content for the bricks for each temple (Fig. 4), three groups can be distinguished. Prasat O Phaong, Prasat Khla Khmum, Prasat Kraham (I & II), Prasat Rong Chen, and Prasat O Top have both higher magnetic susceptibility and Rb content and are categorized as Group A. Temples with low Rb content but with high magnetic susceptibility include Prasat Damrei, Prasat Thma Dap, Prasat Khting Slap, Prasat Koki, Prasat Neak Ta, Prasat Chrei, and Prasat Anlong Thom, and are categorized as Group B. The rest of the temples are categorized as Group C. The temples in Group A tend to be relatively well-preserved, while those in Group C tend to have more severe deterioration. This suggests that the temples in Group A are important and may have been maintained by local people, or that these early temples were constructed with greater care, resulting in better preservation.

Based on the average magnetic susceptibility and Rb content, the surveyed temples can be divided into three groups. The temples classified in Group A are enclosed in a red square frame, the temples in Group B are enclosed in a blue square frame, and the temples in Group C are enclosed in a green square frame.

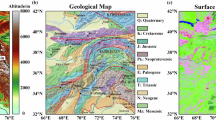

Figure 5 shows a plot of average Sr content versus average Rb content of the gray sandstone at each temple. The gray sandstone blocks at each temple have an Sr content ranging from 150 to 200 ppm, with no significant differences observed between the temples. In contrast, the average Rb content varies widely, ranging from 60 to 140 ppm. According to Uchida et al.23, the Rb content of the gray to yellowish-brown sandstone used in the Angkor monument ranges from 50 to 95 ppm. The gray sandstones used in the temples classified as Group A, including Prasat O Phaong, Prasat Khla Khmum, Prasat Kraham (I & II), Prasat Rong Chen, and Prasat O Top, have relatively high Rb content values ranging from 95 to 140 ppm. There are no significant differences in magnetic susceptibility among the gray sandstone blocks of these temples, with average values ranging from 0.5 × 10−3 to 2 × 10−3 SI units. According to Uchida et al.23, the magnetic susceptibility of the gray to yellowish-brown sandstone supplied from the southeastern foothills of Kulen Mountain ranges from 0.5 × 10−3 to 7 × 10−3 SI units, which is similar to the values for the gray to yellowish-brown sandstone used in the Angkor monument. Kulen Mountain is primarily composed of Cretaceous siliceous sandstone, with gray to yellowish-brown sandstone (the Phu Kradung Formation, referred to as the Red Terrain Formation in Cambodia) from the Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous located at its base24. The siliceous sandstone consists of three layers: the Phra Wihan Formation at the base, the Sao Khua Formation in the middle, and the Phu Phan Formation at the top. In Cambodia, these siliceous sandstones are collectively referred to as the Upper Sandstone Formation. The temples on the summit of Kulen Mountain are built on the Phu Phan Formation, characterized by its white color and presence of small siliceous pebbles that make the procurement of siliceous sandstone relatively easy. However, the use of siliceous sandstone in the temples on the summit of Kulen Mountain is extremely limited. Instead, the sandstone used in these temples is primarily the gray to yellowish-brown sandstone of the Phu Kradung Formation, which constitutes the lower part of Kulen Mountain and is exposed only in the southeastern foothills. The temple on the summit of Kulen Mountain is situated at an altitude of 350 to 430 m above sea level, whereas the formations that yield the gray to yellowish-brown sandstone are distributed at an altitude of ~90 to 120 m above sea level; therefore, this sandstone had to be lifted 250 to 300 m from the quarries to each temple, which suggests that this valuable sandstone was used for the construction of the temples at Mahendraparvata. It is unclear whether the use of the gray to yellowish-brown sandstone as the building material was because of its ease of processing or a preference for its color. However, this sandstone has been used as a building material throughout the Angkor period, including Mahendraparvata. Similarly, a small amount of gray sandstone was commonly used in the pre-Angkorian Sambor Prei Kuk monument.

The blue rectangular frame indicates the range of chemical composition of the gray to yellowish-brown sandstone used in the Angkor monument. The composition of the gray sandstone used in the temples classified in Group A, enclosed in a red ellipse, is plotted outside the blue rectangular frame. In contrast, the gray sandstone used in the temples classified in Groups B and C, enclosed in a green ellipse, is plotted inside the blue rectangular frame.

An interesting result was obtained regarding the positions of the temples classified in Group A. Two groups of temples—Prasat O Phaong, Prasat Khla Khmum, and Prasat Kraham (I & II), as well as Prasat O Phaong, Prasat Rong Chen, and Prasat O Top—are each aligned in a different straight line, with Prasat O Phaong located at the intersection of these two lines (Fig. 2). There may be some relationship between these temples, and they are considered to form a single group. Prasat Damrei Krap is classified as Group B but is situated along the extended line connecting Prasat Kraham (I & II) and Prasat O Top, suggesting a special relationship with these temples (Fig. 2). Based on the high magnetic susceptibility, it can be inferred that Prasat Damrei Krap was the earliest constructed temple among those in Group B. There are a number of examples of several temples or monuments being aligned in straight lines in Khmer monuments, including, despite the distances between them, the three monuments of Preah Vihear (Cambodia), Wat Phu (Laos), and My Son (Vietnam); the three monuments of Preah Vihear, Preah Khan of Kompong Svay, and Phnom Chisor; and the three monuments of Koh Ker, Preah Khan of Kompong Svay, and Sambor Prei Kuk. Additionally, on a smaller scale, the three temples of Phnom Bakheng, Phimeanakas, and Baphuon in the Angkor area are also aligned.

According to Chevance et al.7, Prasat O Phaong is located at the intersection of major east-west and north-south roads, indicating its significance. Unlike other temples, Prasat Rong Chen is primarily constructed of laterite and is considered to be one of the earliest built temples on the summit of Kulen Mountain7.

In addition, the trend of changes in the chemical composition of brick and gray sandstone materials suggests that the temples in Group A were built first, followed by the temples in Group B, and finally the temples in Group C.

Although the 18 temples on the summit of Kulen Mountain that were investigated in this study were divided into three groups, unfortunately, no remains of kilns used for firing the bricks have been found so far.

Temporal changes in brick thickness used in construction

The average thickness of the bricks used in the temples on the summit of Kulen Mountain ranges from 50 to 60 mm. According to Shimoda et al.25, the Sambor Prei Kuk monument, which consists of pre-Angkorian temples and is registered on the World Heritage List of UNESCO in 2017, has an average brick thickness ranging from 50 to 80 mm for each temple, with a decreasing trend of brick thickness over construction time within the same site. In the temples on the summit of Kulen Mountain, the brick thickness ranges from 50 to 60 mm, trending toward thinner bricks similar in thickness to the late-period bricks of the Sambor Prei Kuk monument. According to Uchida et al.26, the bricks used in the Bakong and Phnom Bakheng temples of Hariharalaya (the Roluos monument), the successor to Mahendraparvata, tend to be even thinner (~40 mm). This indicates a decreasing trend of brick thickness from the Sambor Prei Kuk monument to the Roluos monument over time. The thickness of the bricks used in the temples on the summit of Kulen Mountain appears to continue the trend observed in earlier periods. However, in the relatively old temples of the Angkor monument constructed from the late 9th to the 10th centuries, which were predominantly built with bricks, there is a trend toward increasing brick thickness over time (ranging from ~40 to 80 mm)26.

Conclusions

(1) An investigation of building materials was conducted at 18 temples on the summit of Kulen Mountain. The results revealed that, except for Prasat Rong Chen (constructed mainly of laterite), the primary building material for these temples was brick, with a small amount of gray sandstone used for door frames, stairs, and lintels. Some siliceous sandstone was also identified as an exception.

(2) The gray sandstone has magnetic susceptibility and chemical composition (Sr and Rb contents) similar to the gray to yellowish-brown sandstone used in the Angkor monument and may have been quarried from the Phu Kradung Formation at the southeastern foothills of Kulen Mountain.

(3) Systematic differences were observed in the average magnetic susceptibility and average Rb content of the bricks. In addition, based on the average Rb content of the gray sandstone, the 18 surveyed temples can be divided into three groups (Groups A, B, and C).

(4) The Group A temples Prasat O Phaong, Prasat Khla Khmum, and Prasat Kraham (I & II), as well as Prasat O Phaong, Prasat Rong Chen, and Prasat O Top, lie on two straight lines, with Prasat O Phaong located at the intersection of the two lines. Moreover, based on the magnetic susceptibility and chemical composition of the brick and sandstone materials from these temples, it can be concluded that these temples form a single group and were likely constructed during the earliest period of the temples on the summit of Kulen Mountain.

(5) The temples in Group A exhibit a special relationship in their positions and are relatively well-preserved compared with those in Groups B and C. Based on the changes in the chemical composition and magnetic susceptibility of the bricks, it is inferred that the temples were constructed in the following order: Group A, followed by Group B, and then Group C.

(6) The thickness of the bricks used in the temples on the summit of Kulen Mountain is between the thickness of the bricks used in the Sambor Prei Kuk monument of the pre-Angkorian period and those used in the temples of Hariharalaya, the second capital of the Angkorian period. This suggests that there was a technical connection in brick manufacturing between these regions.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Evans, D. et al. Comprehensive archaeological map of the world’s largest preindustrial settlement complex at Angkor, Cambodia. PNAS 104, 14277–14282 (2007).

Chevance, J. B. Inscriptions du Phnom Kulen: corpus existant et inscriptions incrédites, une mise encontexte. Bull. de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient 100, 201–230 (2014).

Penny, D., Chevance, B. P., Tang, D. & De Greef, S. The environmental impact of Cambodia’s ancient city of Mahendraparvata (Phnom Kulen). PLoS ONE 9, e84252 (2014).

Chevance, B. P. Banteay, palais royal de Mahendraparvata. Asèanie 33, 279–330 (2015).

Evans, D. et al. Uncovering archaeological landscapes at Angkor using lidar. PNAS 110, 12595–12600 (2013).

Evans, D. Airbone laser scanning as a method for exploring long-term socio-ecological dynamics in Cambodia. J. Archaeol. Sci. 74, 164–175 (2016).

Chevance, J. B., Evans, D., Hofer, N., Sakhoeun, S. & Chhean, R. Mahendraparvata: an early Angkor-period capital defined through airborne laser scanning at Phnom Kulen. Antiquity 93, 1303–1321 (2019).

Uchida, E., Cunin, O., Shimoda, I., Suda, C. & Nakagawa, T. The construction process of the Angkor monuments elucidated by the magnetic susceptibility of sandstone. Archaeometry 45, 221–232 (2003).

Uchida, E., Cunin, O., Suda, C., Ueno, A. & Nakagawa, T. Consideration on the construction process and the sandstone quarries during Angkor period based on the magnetic susceptibility. J. Archaeol. Sci. 34, 924–935 (2007).

Uchida, E., Tsuda, K. & Shimoda, I. Construction sequence of the Koh Ker monuments in Cambodia deduced from the chemical composition and magnetic susceptibility of its laterites. Herit. Sci. 2, 1–11 (2014).

Uchida, E., Mizoguchi, A., Sato, H., Shimoda, I. & Watanabe, R. Determining the construction sequence of the Preah Vihear monument in Cambodia from its sandstone block characteristics. Herit. Sci. 5, 1–15 (2017).

Uchida, E., Sakurai, Y., Cheng, R., Shimoda, I. & Saito, Y. Supply ranges of stone blocks used in masonry bridges and their construction period along the East Royal Road in the Khmer Empire, Cambodia. Herit. Sci. 8, 1–16 (2020).

Imai, N., Terashima, S., Itoh, S. & Ando, A. 1994 compilation values for GSJ reference samples, “Igneous rock series. Geochem. J. 29, 91–95 (1995).

Potts P. J., West M. Portable X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometry. Capabilities for In-situ Analysis (RSC Publishing, 2008).

Mendoza Cuevas, A., Bernardini, F., Gianoncelli, A. & Tuniz, C. Energy dispersive X-ray diffraction and fluorescence portable system for cultural heritage applications. X-ray Spectrom. 44, 105–115 (2015).

Tykot, R. H. Using nondestructive portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometers on stone, ceramics, metals, and other materials in museums: advantages and limitations. Appl. Spectrosc. 70, 42–56 (2016).

Williams-Thorpe, O. & Thorpe, R. S. Magnetic susceptibility used in non-destructive provenancing of Roman granite columns. Archaeometry 35, 185–195 (1993).

Williams-Thorpe, O., Jones, M. C., Tindle, A. G. & Thorpe, R. S. Magnetic susceptibility variations at Mons Claudianus and in Roman columns: a method of provenancing to within a single quarry. Archaeometry 38, 15–41 (1996).

Williams-Thorpe, O., Jones, M. C., Webb, P. C. & Rigby, I. J. Magnetic susceptibility thickness corrections for small artefacts and comments on the effects of background materials. Archaeometry 42, 101–108 (2000).

Alva-Valdivia, L. M., Agarwal, A. & Cruz-Y-Cruz, T. Magnetic Susceptibility. in Encyclopedia of Archaeological Science (eds Lόpez Varela, S. L.) 1–4, (Wiley, 2018).

Tanikawa, W. et al. Provenance of granitic gravestones in graveyard of feudal lords evaluated by multiple non-destructive rock analyses. J. Cult. Herit. 56, 183–192 (2022).

Uchida, E., Ito, K. & Shimizu, N. Provenance of the sandstone used in the construction of the Khmer monuments in Thailand. Archaeometry 52, 550–574 (2010).

Uchida, E., Watanabe, R., Cheng, R., Nakamura, Y. & Takeyama, T. Non-destructive in-situ classification of sandstones used in the Angkor monuments of Cambodia using a portable X-ray fluorescence analyzer and magnetic susceptibility meter. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 39, 103137 (2021).

Meesook, A. et al. Mesozoic rocks of Thailand: a summary. In: Proc. Symposium on Geology of Thailand. 82–94 (2002).

Shimoda, I., Uchida, E. & Tsuda, K. Estimated construction order of the major shrines of Sambor Prei Kuk based on an analysis of bricks. Heritage 2, 1941–1959 (2019).

Uchida, E., Maeda, N. Petrology. In: Annual Report on the technical Survey of Angkor Monument 1999, Japanese Government Team for Safeguarding Angkor. 247–291, (JSA, 1999).

Acknowledgements

We received permission from the APSARA Authority of Cambodia to conduct this survey. The staff of the Japanese Government Team for Safeguarding Angkor assisted us in obtaining permission to conduct this survey. We thank Edanz for editing a draft of this manuscript. This research was financially supported in part by Grants-in-Aids for Open Partnership Joint Research Projects (Uchida: JPJSBP1202199401) and Scientific Research (Uchida: 19KK0016) of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.U., A.M., K.K., and K.A. conducted investigation, interpreted data, and draw figures. E.U. wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Uchida, E., Mizumori, A., Kuriyama, K. et al. A study on the possible construction order of the temples in Mahendraparvata on the summit of Kulen Mountain, Cambodia, based on brick and sandstone materials. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 15 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01576-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01576-3