Abstract

This study investigates the spatial genotypes of traditional Tibetan dwellings in Ganzi County, China, using the Justified Plan Graph (JPG) method and a dataset of 12 houses across three historical periods. The analysis focuses on spatial integration (i) values and control (CV) values, combined with Z-score standardization to ensure comparability. The results reveal changes in spatial layouts driven by social transformations. In early houses, open terraces (OT) (e.g., House 1: Zi = 2.55, Zcv = 2.42) served as key spaces for agrarian lifestyles, while inner yard corridors (C) in aristocratic houses (e.g., House 3: Zi = 3.2, Zcv = 3.7) reflected formal social organization. Later houses shifted to multi-core layouts. For example, in House 4, H (Zi = 1.99, Zcv = 1.74) and OT1 (Zi = 1.99, Zcv = 1.37) jointly serve as organizational cores, balancing traditional and modern functions. In contemporary and modern houses, circulation spaces halls (H) and corridors (C) dominate spatial organization, as seen in House 8, where C (Zi = 3.26, Zcv = 3.13) reflects the trends of functional optimization and spatial homogenization. Spaces such as storage (S), chanting hall (CH), and toilet (T) consistently exhibit low i and CV values, reflecting a historical continuity in the need for privacy. Overall, traditional design principles persisted in houses built as recently as 30 years ago, with significant changes in spatial layouts only emerging in the past decade. These findings reveal the evolution of Tibetan dwelling layouts, providing insights for their preservation and adaptation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traditional Chinese houses confront significant challenges in the modern era as rapid urbanization and modernization threaten their preservation and development. These challenges include preservation issues stemming from demolition and lack of funding, adaptability concerns related to changing family structures and modern amenities, economic viability difficulties, and a general lack of public awareness and appreciation.

Especially in the traditional Tibetan areas, although the forms and styles of architecture have survived throughout history, the modernized way of life and production has had a tremendous impact on them. Some Tibetan communities still gather in Sichuan, Qinghai, and Gansu in China, especially in Ganzi County in Sichuan, where a considerable number of Tibetans gather. Since these areas are not the core area of Tibetan culture, the traditional way of life in this area is more vulnerable as other cultures continue to influence it. Due to the treacherous terrain of these places, some historical architectural remains are still preserved, which are highly praised by the local people. The Tibetan dwellings in Ganzi County are unique in their spatial structure, shaped by local geography, climate, and cultural practices, reflecting social hierarchy, religious beliefs, and community interactions. Field investigations revealed that certain historical dwellings underwent unauthorized modifications by non-residents for exhibition, resulting in a failure to maintain their inherent spatial configuration. Additionally, in relocated or post-disaster reconstruction buildings, the spatial design of new structures often does not fully meet the living and production needs of local residents. To address this issue, identifying the genotypes of local traditional housing can help architects understand the social-spatial logic of these homes and make more informed decisions.

Spatial syntax is a set of theories, methods, and techniques developed by Bill Hillier and his team at University College London to investigate the relationships between spatial configuration and social interaction1. Rooted in mathematical principles, spatial syntax analysis uses topological data to represent spatial organizations and the resulting social structures without prioritizing measurable spatial properties, thus providing researchers with a practical tool to establish correlations between spatial configurations and social behaviors2,3. Space syntax is also regarded as a scientific methodology for investigating the historical characteristics and morphological qualities of the built environment4,5,6. In spatial syntax studies, the use of axial and convex maps enables the analysis of morphological changes in historic buildings, thereby facilitating the formulation of appropriate design interventions7,8,9,10.

In the context of spatial syntax analysis, the Justified Plan Graph (JPG) provides a graphical and mathematical model for analyzing the spatial configuration of a building and assessing the spatial permeability of a built environment11,12,13. There are typically three models of JPG: shallow tree, deep tree, and ring (Fig. 1). Model (a) shows a shallow tree structure with few layers, meaning the space is accessible from the outside. Model (b) is a deep tree structure with many layers and a hierarchical organization, often representing a linear layout with specific functions. Model (c) is a ring structure with alternative routes between parts of the pattern, suggesting higher spatial connectivity and navigational flexibility. These models enable a deeper exploration of hidden behavioral patterns and social interactions within built environments14.

Although initially introduced in Hillier’s and Hanson’s books, it did not generate significant interest and there was only a limited number of research articles on this approach15,16. This is likely due to the lack of a comprehensive explanation of the JPG method. In 2011, Ostwald from the University of Newcastle School published two articles in the Nexus Network Journal, presenting a scientific framework for the analysis and mathematical calculation steps of the justified plan graph (JPG) method17,18. Inspired by Ostwald’s work, recent studies have applied the JPG method to various contexts. For example, Jeong and Ban (2014) used the method to analyze spatial patterns in Korean apartments, revealing changes in functional and spatial configurations over time19. Similarly, Elizondo (2022) examined social housing in Monterrey, Mexico, using JPG to assess transformations in spatial structures across different historical periods20. Additionally, the method has been employed in the study of historical architecture, such as Palladian villas, to understand the underlying spatial logic and visitor-inhabitant relationships14,22,2321. In vernacular architecture, the JPG method has been applied to understand spatial and cultural dynamics in various regions. Kamelnia et al.24 explored traditional courtyards in Iran, revealing shifts in accessibility and privacy in core spaces24. Similarly, Asif et al.25 investigated the socio-spatial arrangements in traditional Malay houses, demonstrating how spatial organization supports cultural practices25.

The JPG method enhances traditional space syntax by offering hierarchical visualization, precise quantification of spatial properties, and effective analysis of socio-spatial dynamics17,16. It allows systematic comparison and tracing of spatial evolution, revealing configurations often missed by traditional methods12. This makes it particularly suitable for analyzing the complex layouts of Tibetan dwellings in Ganzi County. Despite its strengths, JPG has been underutilized in rural vernacular studies, particularly in the systematic extraction of spatial genotypes and the exploration of cultural and social factors influencing these genotypes over time, especially in culturally rich Tibetan regions. Existing studies often focus on general architectural functionality, neglecting the temporal and cultural dynamics reflected in spatial genotype evolution25. Recent studies, such as An et al.26, have demonstrated the potential of the JPG method in analyzing Tibetan vernacular dwellings, particularly in revealing spatial isomerism and socio-cultural significance26. Based on these advancements, this study applies the JPG method to extract and compare spatial genotypes of Tibetan dwellings across different historical periods, uncovering the socio-cultural factors that drive changes in these genotypes. Such an approach offers a novel lens for understanding the interplay between spatial organization and cultural heritage in Tibetan vernacular architecture.

Instead of JPG analysis, Visibility Graph Analysis (VGA) can focus on visual connections within a space, making it particularly useful for environments where sightlines and spatial awareness are crucial33. Recent studies have also integrated spatial syntax with system dynamics to examine spatial changes over time, offering insights into evolving layouts34. Although alternatives like Visibility Graph Analysis (VGA) and system dynamics integration provide insights into visual connections and spatial changes, they lack the depth and cultural specificity needed for Tibetan architecture. The JPG method can provide a comprehensive analysis of vernacular architecture with a culturally rich background, which is quite important for this study14.

The AGRAPH software, developed by Delft University of Technology, is a PC application designed for drawing spatial syntax graphs and performing spatial syntactic calculations. It provides graphical and data validation support for this study27,28.

Study areas and objects

Ganzi County, located in the northwest of Ganzi Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Sichuan Province, China, is a key area for this research (Fig. 2a). Situated on the southeastern edge of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, the region is characterized by diverse topography, including undulating mountains, river valleys, and elevations averaging 3500 meters, with Gongga Mountain reaching a peak of 7556 meters. It is crossed by major rivers such as the Yalong, Jinsha, and Dadu Rivers. Ganzi County lies within the active “Kangding-Ganzi” seismic zone, historically prone to frequent earthquakes.

Historically, Ganzi County has served as the political, economic, and cultural hub of northern Kham, holding significant strategic importance as a junction along the ancient Tang-Tibetan route, facilitating trade between Lhasa and inland China. The broad valleys of the Yalong River, which provide fertile agricultural land, have supported dense populations and economic development (Fig. 2a). The Hor tribe, which gained prominence during the Yuan Dynasty and evolved into a ruling Tusi family by the Qing Dynasty, significantly shaped the region’s culture and architecture until the mid-20th century. In this socio-historical context, the traditional dwellings in Ganzi County exhibit certain characteristics of cultural integration, which themselves serve as a manifestation of local distinctiveness. Moreover, this integration has undergone a certain evolutionary process over the course of history.

Most of the existing traditional houses in Ganzi County are two stories high, with some older houses reaching three or even four stories. These houses reflect the local semi-farming and semi-pastoral lifestyle. The ground floor of the house is primarily used as animal stables (AS), the first floor serves as the main living area for the family, including spaces such as the living room (LR), bedroom (BR), kitchen (K), chanting hall (CH), toilet (T), and storage (S). Houses with three or four stories typically include an semi-open grain drying shed. These dwellings are often located in river valleys near water sources, with an average covered area of 300 to 500 square meters, and are constructed using wooden beams and columns with rammed earth walls (Fig. 3).

The study area focuses on the core region of the Yalong River valley in Ganzi County, specifically encompassing the Ganzi Town and the townships of Shengkang, Kagong, Xiala. This region serves as the primary agricultural hub and is the core governance area of Tusi strongholds. It includes four national-level traditional villages, along with several others that, while not officially recognized, retain well-preserved village forms and buildings. The research primarily investigates traditional dwellings in these national-level villages, supplemented by others. Given the historically complex social structure, the dwellings in this area comprise Tusi residences, aristocratic residences (headmen or chiefs), farmers’ houses, merchants’ houses, Monks’ houses and settled pastoralists’ houses.

To clarify the historical evolution of housing genotypes and their relationship with social activities, twelve representative cases from four villages (Fig. 2b) were selected based on the following criteria: 1) identifiable construction dates, 2) preserved original exterior appearance, and 3) known or still-functioning interior spatial functions. These 12 houses span 200 years: houses 1-7 are older traditional houses, houses 8-10 were built about 30 years ago and are widely present, and houses 11–12 were newly constructed in the last 10 years with distinctive features. Table 1 details these selected houses, Table 2 provides the letter abbreviations for each type of space in the twelve houses, and Fig. 4 provides the Floor plans and JPGS.

Methodology

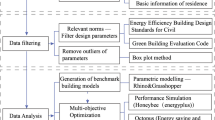

In the spatial analysis of the twelve selected houses in Ganzi County, this paper will use the following four processes to conduct a graphical and mathematical analysis of each space, and will then use tables and graphs to compare and summarize the data, and finally extract the genotypes of house space.

Drawing JPG

To mathematically analyze the justified plan graph (JPG), the first step is to transform the architectural plans into a “convex map” that identifies spaces and their connections. Hillier and Hanson define a convex space as one where “no line drawn between any two points in the space goes outside the space”16. However, overly detailed segmentation can complicate spatial nodes, making it harder to understand the house’s spatial logic. Recent research favors drawing convex maps by associating spaces with functional zones, reducing the number of nodes and more closely aligning with inhabitation patterns29,30,31,32.

In this paper, convex maps are drawn using architectural labels as boundaries. Once the convex map is established, a justified plan graph is created. Each space is represented as a circular node, numbered alphabetically by function (e.g., BR1, BR2 for bedrooms), with the exterior shown as a crossed circle (⊕). The nodes are arranged in horizontal layers indicating depth: line 0 typically represents the outside, with other lines representing spaces connected to the previous layer. Links between nodes are drawn as lines: dashed for connections to the exterior, solid for connections within the same floor, and break lines for connections across floors (Table 3).

Mathematical analysis

Step 1: Determine the total number of graph nodes K. For example, in Fig. (1c). K = 8(that is, there are 8 nodes: ⊕, H1, K, CO, L, H2, BR, T). At the same time, the depth L of each node relative to the carrier ⊕ is marked. There are 5 levels of depth. (0, 1, 2, 3, 4) in Fig. (3c), the depth L value for node H2 = 3.

Step 2: Calculate the total depth of the graph for a given space node, denoted TD. Equation (1) outlines the expression for calculating the total depth4. The nX in the equation represents the total number of space nodes in a given level.

Step 3: Mean depth MD refers to the average depth of spatial nodes in a reasonable floor plan (Ostwald, 2011). MD is calculated by dividing the total depth TD by the number of graph nodes K minus one (i.e., excluding itself)17.

Step 4: The relative asymmetry RA can be used when there is a need to compare and analyze the TD and MD results when there are two housing estates with different numbers of spatial nodes. However, if the K values (total number of space nodes) become too dissimilar, the accuracy of this comparison will be reduced, as shown in step 6 below. This term describes an important method of normalizing the range of possible results to between 0.0 and 1.02. The RA of a carrier space reflects its relative isolation. The formula is:

Step 5: The degree of integration iRA of a space node in JPG can be calculated by taking the reciprocal of the RA.

However, when comparing buildings of radically different sizes, a comparison must be constructed against an optimal benchmark (see Step 7).

Step 6: When buildings with radically different K values, Real Relative Asymmetry RRA values can be used instead of Relative Asymmetry RA for analysis. The RRA analysis develops a scalable spatial configuration that can be utilized to analyze sets of results in a relative manner. To achieve this, a diamond-shaped configuration is selected and its RA value is denoted as the D value to signify this initial stage. A lower RRA value means a higher level of integration, while a higher RRA value means a higher degree of resolution.

The RRA is produced by dividing the subject RA by the relativized RA or D, and D for a K can be obtained from Hillier and Hanson’s table16.

Step 7: When using RRA to represent the relative isolation of nodes in JPG, the degree of integration i can be calculated as:

The degree of integration reflects the accessibility and importance of a space within the entire layout. Specifically, the lower the iRRA value, the more easily accessible the space is relative to others, indicating higher integration. This typically means that the space is more central and important within the entire layout.

Step 8 The control value CV of a JPG is typically described as being a reflection of the degree of influence exerted by a space in a network. To calculate the CV value of a node, first calculate the numeric Ncn value of each node that is directly connected to other nodes. Since “each space provides its neighbor with a value equal to 1/n of its ‘control’” (Shapiro, 2005). The distributed or shared value of each node is called Cve, and Cve = 1/ Ncn. In the end, the CV value of the node is the sum of the Cve values shared by all the nodes directly connected to it.

These are all the values involved in the analytical methodology, and since there are relatively large differences in the number of spaces in the cases selected for this paper, the RRA values will be used instead of the RA values in the final results for the sake of comparable analysis of the values, and the i values will be based on this.

Z-Score standardization of i-values and CV-values

To enable consistent comparisons of i values and CV values across different houses and periods, this study applies Z-score standardization. The Z-score method standardizes each space’s i values and CV values by converting them into a common scale. This process helps identify deviations from the mean, where positive values indicate above-average integration or control, and negative values represent lower values. The formula for calculating the Z-score is:

Where X is the original i-value or CV-value of the space. μ is the mean value for all spaces in the dataset. σ is the standard deviation of the values.

This standardization process is essential for comparing spatial configurations across different houses, allowing for a clearer understanding of how certain spaces function over time in relation to household social and functional needs.

Results

Justified plan graphs

The JPGs of the 12 houses show that although the overall structures remain tree-like, significant changes have occurred within the internal configuration (Fig. 4).

The Justified Plan Graphs (JPGs) of traditional houses exhibit an asymmetric tree-like structure. In early farmer dwellings (e.g., Houses 1 and 2), the open terrace (OT) serves as the central core, with a single core node connecting the primary family spaces through the shortest paths, demonstrating a highly centralized layout. However, some nodes are located at greater depths from the core, with lower accessibility, reflecting a certain demand for privacy. In noble residences (e.g., Houses 3 and 6), the corridor (C) becomes the central core, leading to a clearer spatial organization and improved accessibility, while still maintaining some private spaces that are less accessible. Additionally, the branching in Houses 4, 5, and 7 increases significantly, presenting a multi-core distribution and making the overall spatial structure increasingly asymmetric with separated circulation spaces. This evolution reflects the changes in spatial layout patterns driven by shifting functional demands.

The JPGs of Houses 8 to 12 still exhibit an asymmetric tree-like structure, but significant changes have occurred within their internal organization. In these houses, the spatial layout centers on vertical circulation spaces, such as corridors (C) or halls (H), as core nodes. The control value of the outer yard (Yo) also increases. The multi-core node layout improves spatial accessibility and allows for more efficient movement. The reinforcement of circulation spaces introduces localized symmetry within the overall asymmetry, contributing to the specialization and uniformity of spatial functions. Overall, the JPGs reflect the increasing number of control nodes in Ganzi County’s houses as they adapt to evolving social needs, as layouts transition from compact and imbalanced to more dispersed and balanced arrangements.

Spatial composition

The statistical analysis of the twelve houses identified a total of twenty spatial nodes. A heatmap was generated to visualize their distribution across a 0–35% range, with darker colors representing higher percentages (Fig. 5).

The spatial elements of traditional farming dwellings (Houses 1, 2, 5, 7) reveal a layout rooted in Tibetan values and agricultural-pastoral lifestyle. These houses share common spatial elements such as storage (S), kitchen (K), animal stable (AS), open terrace (OT), chanting hall (CH), living room (LR), and bedroom (BR), reflecting the essential layout required for agricultural activities, animal husbandry, and social interactions in farming households. House 3, 6, built 100 years ago for an aristocratic or merchant family, include inner yard (Yi) and corridor (C) spaces for formal gatherings and social interactions. Similarly, merchant houses like Houses 4 incorporate outer yards (Yo) and corridors (C) to facilitate commercial and social functions. Nevertheless, even among these aristocratic and merchant families, traditional agricultural and pastoral spaces are still preserved, indicating a continued connection to their traditional livelihoods.

The contemporary farmhouses were generally built around 30 years ago, with House 8 to House 10 being the most representative examples of contemporary farm dwellings in the Ganzi region. Although still featuring essential agricultural spaces such as open terrace (OT) and storage (S), these farming households have begun expanding their ground-floor outer yards (Yo), and use the space porch (PO) frequently for more complex activities. Houses 11 and 12, built within the last 10 years as a restaurant and guesthouses, showcase the impact of modernization and urbanization. Their spatial focus has shifted to commercial functions, reflecting a trend toward adapting traditional spaces for tourism, which is influenced by Han culture.

The heatmap analysis indicates a consistent presence of fundamental spatial elements in traditional houses, particularly in farmhouses. Core elements such as storage (S), kitchen (K), bedroom (BR), living room (LR), animal stable (AS), chanting hall (CH), toilet (T), and open terrace (OT) are consistently found across these farmhouses, emphasizing their alignment with the agricultural-pastoral lifestyle and Tibetan Buddhist practices. However, other types of households, such as aristocratic or merchant houses, exhibit slight variations. These houses may include spatial, elements for formal gatherings, such as inner yards (Yi) and corridors (C). In the past decade, with the advent of modernization and urbanization, the spatial composition elements have become more diverse and complex.

Syntactic measures

In this study, after extracting the i values and CV values of various spaces, standardized processing and analysis were conducted (Table 4). Spatial Heatmaps were created for each sample house (Fig. 8). A diachronic analysis was conducted focusing on the values of spaces H, C, Yo, OT, and LR (Fig. 6). These visualizations provide a deeper understanding of the evolution of architectural spatial structures and changes in human behavior patterns.

Spaces with high i (Zi > 1) and CV values (Zcv > 1)

When Z > 1, it indicates that the data point deviates significantly from the mean and is considered a high value within the overall dataset. This serves as the basis for evaluating core spaces in this study.

OT (Zi = 2.55, Zcv = 2.42) in House 1 and OT (Zi = 3.4, Zcv = 3.45) in House 2 all stand out in these two houses. In House 3, key spaces include C (Zi = 3.2, Zcv = 3.7) and LR (Zi = 1.17, Zcv = 2.62). In House 4, the halls include H1 (Zi = 2.99, Zcv = 1.3) and H2 (Zi = 1.48, Zcv = 1.68), which are prominent. In House 5, H (Zi = 1.99, Zcv = 1.74) and OT1 (Zi = 1.99, Zcv = 1.37) emerge as key spaces. In House 6, C (Zi = 2.93, Zcv = 2.2) is prominent. For House 7, Yo (Zi = 2.14, Zcv = 1.24) and OT (Zi = 2.14, Zcv = 1.96) hold significant roles.

In Houses 8 to 12, spaces with high i (Zi > 1) and CV values (Zcv > 1) are limited to halls and corridors, highlighting the importance of circulation spaces. Specific values are as follows: in House 8, C (Zi = 3.26, Zcv = 3.13) and H (Zi = 1.37, Zcv = 1.14); in House 9, C (Zi = 2.82, Zcv = 3.00) and H (Zi = 1.96, Zcv = 1.77); in House 10, H2 (Zi = 2.69, Zcv = 2.81) and H1 (Zi = 1.67, Zcv = 1.99); in House 11, C1 (Zi = 3.31, Zcv = 2.78) and C2 (Zi = 1.76, Zcv = 2.28); and in House 12, H3 (Zi = 2.19, Zcv = 1.46), H1 (Zi = 2.84, Zcv = 1.31), and H2 (Zi = 1.53, Zcv = 1.08).

Spaces with relatively high i but lower CV values

Spaces include H in House 1 (Zi = 1.35, Zcv = 0.52) and House 2 (Zi = 1.01, Zcv = 0.35), as well as AS (Zi = 1.3, Zcv = 0.72) and the Yi (Zi = 1.3, Zcv = −0.23) in House 6. Additionally, Yo in House 12 (Zi = 0.8, Zcv = 0.27) demonstrates moderate integration. These spaces may serve as local hubs within the spatial structure of the houses.

Spaces with relatively high CV but lower i values

Spaces include the LR in House 1 (Zi = −0.05, Zcv = 1.37) and AS in House 2 (Zi = −0.26, Zcv = 1.08). In House 4, both C (Zi = 0.75, Zcv = 2.18) and OT (Zi = 0.46, Zcv = 1.17) exhibit this pattern. Similarly, BR in House 5 (Zi = 0.19, Zcv = 1.37) and BR1 (Zi = 0.57, Zcv = 1.28) and PO (Zi = −0.72, Zcv = 1.65) in House 6 highlight this trend. Other examples include H in House 7 (Zi = 0.52, Zcv = 1.96), LR in House 8 (Zi = 0.43, Zcv = 1.14), Yo in House 11 (Zi = 0.17, Zcv = 2.21), and C3 in House 12 (Zi = 0.90, Zcv = 3.51). These spaces likely function as localized control points within the spatial organization.

Spaces with low i and low CV values

Spaces, such as the grain drying shed (GD), hay room (HR), kitchen (K), storage (S), chanting hall (CH), and toilet (T) have low i values and CV values. The Zi and Zcv values of these spaces are generally less than 0, indicating that the data points are below the mean. This suggests that these spaces are typically located at the periphery of the structure and are less accessible. These spaces are likely related to the need for privacy or serve primarily as auxiliary spaces for daily activities (Table 1, Fig. 8).

When conducting diachronic analysis of the values for H, C, Yo, OT and LR, the highest value was used when multiple similar spaces existed within a house. The study focuses on typical houses, excluding Houses 3 and 6 due to their unique historical spatial structures, which limit their comparability with other houses. When certain spaces are absent, the value of Z is set to -1 (Fig. 6).

Halls (H) consistently maintain high i and CV values across all periods, emphasizing their stable and central role in spatial organization. Corridors (C) show a significant increase in both i and CV values in contemporary and modern houses, reflecting their growing importance as traffic and connection hubs. Outer yards (Yo) display a marked rise in integration and control in modern houses, highlighting their increasing functional and social significance. Meanwhile, open terraces (OT) are highly integrated and controlled in historical houses, like houses 1 and 2, but their importance diminishes in contemporary layouts. Living rooms (LR) consistently show low integration but maintain moderate control in traditional houses, gradually losing their hierarchical importance in modern layouts. Overall, these trends reflect a shift in spatial organization, with modern houses increasingly emphasizing interior connectivity and the renewed importance of outdoor courtyards, driven by evolving cultural and functional priorities. (Fig. 6).

Spatial connection patterns

To further explore the spatial genotypes of the houses, the study also conducted an analysis of spatial connection patterns. It also calculated the connection values for each type of spatial connection pattern in Houses 1-7, 8-10, and 11-12, and conducted a comparative analysis.

The spatial connection patterns in Houses 1-7

The main connection patterns are as follows: S-LR has the highest connection, with a value of 7. K-OT and K-W each have a connection value of 3. GD-OT is closely connected with a value of 4. AS-HR and AS-H both have a connection value of 3. CH-BR is consistently connected, while BR-OT and BR-H each have a connection value of 3. H serves as a central node, with strong connections to K-OT and other spaces. The chord diagram below provides an intuitive understanding of the differences in connections, with thick lines indicating stronger connections and thin lines indicating weaker ones (Fig. 7).

The spatial connection patterns in Houses 8-10

In contemporary Houses 8-10, some traditional spatial connection patterns with specific connection values are still preserved, including AS-H, AS-HR, HR-H, S-LR, OT-T, LR-CH, and K-W. Unlike traditional houses, the high connection values in these three houses are primarily concentrated on the connections between the corridor (C) and other main functional spaces, and the halls (H). Notably, all three houses feature a connection between the outer yard (Yo) and the halls (H).

The spatial connection patterns in Houses 11-12

The spatial connection patterns in Houses 11-12 have undergone significant changes, with most of the traditional connection patterns nearly disappearing, replaced by strong connections between the corridor (C) and other main functional spaces. Additionally, the outer yard (Yo) is connected with more auxiliary spaces, resembling the spatial organization typically found in modern rural houses in Han regions.

Discussion

Types of house genotypes

Houses in Ganzi County have different features that reflect the lifestyles of their inhabitants and their social status. Based on the above calculations and graphical analysis, the spatial genotypes of houses in Ganzi County can be classified into four types. The changes in genotypes are visually illustrated in Fig. 8.

Traditional house genotype

Open terrace-dominated houses (genotype I: houses 1, 2)

This spatial genotype is characteristic of early farmers’ houses in Ganzi County. In this genotype, the open terrace (OT) functions as the dominant core space, reflecting its significance in early agrarian lifestyles. The open terrace demonstrates high spatial integration and control (Zi ≥ 2, Zcv ≥ 2), which makes it the primary hub for activities. Secondary spaces, such as the hall (H) and outer yard (Yo), show moderate integration, serving as transitional zones that connect private and public areas. Peripheral spaces like the living room (LR) and animal stable (AS) offer limited connectivity but retain some control in the spatial hierarchy. This layout reveals a single-core organization centered around the open terrace, with private spaces loosely connected to the core.

Inner yard corridor-dominated house (genotype II: houses 3, 6)

This genotype is characteristic of aristocratic or merchant households, emphasizing formal interactions and social status. The inner yard corridor (C) serves as the central organizing element, exhibiting high levels of both integration and control. Other spaces, such as the living room (LR) and animal stables (AS), also hold significant roles, reflecting the diverse functional demands of these households. The spatial organization in this genotype is marked by high coherence and fluidity, with multiple secondary nodes supporting public and formal activities. This is a historically unique genotype, as houses combining inner yards with corridors are relatively rare among the preserved dwellings in Ganzi County.

Multiple nodes-dominated house (genotype III: houses 4, 5, 7)

These houses represent a transition from traditional agrarian to semi-modern lifestyles. Unlike the single-core structure of earlier genotypes, this type features a multi-core layout, with halls (H1, H2) and open terraces (OT) sharing the role of organizational cores. This configuration provides more diverse traffic routes and accommodates both agricultural and social functions. For instance, the hall and open terrace form dual cores in House 4, while in Houses 5 and 7, open terraces (OT) play a reduced role as halls across different floors gain prominence. This evolution reflects an adaptation to changing functional needs, moving towards a balance of domestic and social spaces.

ii. Contemporary and modern house genotype

Circulation-dominated spatial genotype (genotype IV: houses 8-12)

In these houses, spatial connection patterns shift significantly, with the corridor (C) emerging as the dominant core. Traditional strong connections, such as those with open terraces (OT), diminish or disappear, while corridors connect directly to key functional spaces like halls (H) and activity areas. This shift indicates a reorganization of space to prioritize circulation and efficiency. Additionally, the connection between outer yards (Yo) and halls (H) is consistently observed, and the increasing CV values of the outer yard (Yo) suggests that it is emerging as a local central node within the house's spatial layout.

Relationship between household activities and spatial genotypes

The transition from single-node-dominated houses to circulation-dominated house in Ganzi County illustrates the household activities within different socio-cultural contexts. This section will further explore the differences and consistency in these household activities, which help us gain a deeper understanding of the evolution of the genotypes.

Differences in public activity spaces

In traditional farmhouses, open terrace (OT) accommodates agricultural and social activities like grain drying, ritual offerings, and gatherings, essential for both livelihood and social cohesion. It symbolizes shared responsibility and public life, reflecting the intertwined economic and social aspects of Tibetan rural life. While in contemporary and modern houses, the organization of circulation spaces has led to the gradual homogenization of family public spaces such as open terrace (OT) and living room (LR). However, it is important to note that outer yards (Yo) have gained increasing prominence, becoming key venues for family public activities. This transformation reflects the impact of social development and ethnic integration.

Additionally, traditional noble and merchant families were usually large households that needed public activity spaces and optimized circulation provided by inner yards (Yi) and corridors (C). In contrast, families in modern society are typically smaller nuclear units, and as modern economic activities have become more focused on external trade, commerce, and services, the enclosed inner yards have lost their significance. As a result, the inner yard corridor genotype has gradually disappeared.

Consistency in private activity spaces

Despite the evolution in public spaces, private spaces across all periods show notable similarities. Spaces like the bedroom (BR), chanting hall (CH), storage (S), and toilet (T) consistently exhibit low i and CV values, reflecting their private, function-specific roles. For instance, the storage room (S) is isolated to ensure security for valuable goods. Similarly, the chanting hall (CH), central to Tibetan Buddhist practice, is placed in secluded parts of the house to maintain spiritual privacy. The toilet (T), while segregated from other areas, has moderate i values but low CV values, ensuring limited interaction with more central spaces.

These specific private space designs have persisted into houses built in the past 30 years. Although modern houses have largely homogenized spatial layouts, these spaces still maintain their privacy. The consistency in private activity highlights the cultural continuity in Tibetan household designs, where private needs are consistently prioritized across different social classes and periods. The design of these spaces reflects not only practical considerations but also deep-rooted cultural and religious values that transcend changes in economic activities.

Spatial behavior patterns under cultural concepts

In traditional Tibetan houses, Tibetan values influenced by valley agriculture, religious beliefs, and the Tusi political system profoundly shape the behavior patterns within the houses. It is noteworthy that the chanting hall (CH) is often accessible only through the bedroom (BR) or living room (LR), underscoring its sacred and private nature, deeply embedded within family life. Additionally, the direct connection between the open terrace (OT) and the grain drying shed (GD) demonstrates the close integration of household production and daily life. The strong connection between storage (S) and the bedroom (BR) or living room (LR) reflects the Tibetan people’s concern for the safety of their family’s property. The toilet (T) are usually only connected to the open terrace (OT), reflecting the Tibetan people’s sense of cleanliness and ecological wisdom.

However, the spatial behavior patterns in modern houses have undergone significant changes. The unique spatial connections within the house have gradually disappeared, leading to a homogenization of spatial functions and greater functional refinement. These changes indicate that the lifestyle and attitudes of Tibetan residents have gradually shifted from being inward-looking and secure to outward-facing and open.

Conclusion

This study applies the Justified Plan Graph (JPG) method to analyze the spatial genotypes of traditional Tibetan dwellings in Ganzi County, focusing on twelve representative houses spanning three historical periods. The findings reveal significant transitions in spatial configurations, reflecting socio-cultural and functional changes over time. Four primary spatial genotypes are identified:

Open Terrace-Dominated Houses (Genotype I), exemplified by Houses 1 and 2, where open terraces (e.g., House 1: Zi = 2.55, Zcv = 2.42) serve as central spaces for agricultural activities, community gatherings, and religious rituals, emphasizing shared responsibilities and social cohesion.

Inner Yard Corridor-Dominated Houses (Genotype II), found in aristocratic or merchant houses, like Houses 3 and 6, featuring inner yard corridors (e.g., House 3: Zi = 3.2, Zcv = 3.7) as organizing cores, supporting hierarchical social interactions and balancing accessibility with privacy.

Multiple Nodes-Dominated Houses (Genotype III), represented by transitional houses like Houses 4, 5, and 7, showcasing a shift from single-core to multi-core layouts where terraces lose dominance to halls (e.g., House 4, Zi = 1.99, Zcv = 1.74) and other spaces, accommodating both domestic and social functions.

Circulation-Dominated Houses (Genotype IV), observed in contemporary and modern houses, where corridors (e.g., House 8, Zi = 3.26, Zcv = 3.13) and halls (e.g., House 8, Zi = 1.37, Zcv = 1.14) dominate as central nodes and, outer yards (Yo) evolve into multifunctional spaces, reflecting functional optimization and spatial homogenization.

Despite these transitions, private spaces such as bedrooms (BR), chanting halls (CH), and toilets (T) consistently exhibit low integration and control, usually with Zi < 0, Zcv < 0, underscoring their enduring role in maintaining privacy across historical periods.

The analysis of spatial connection patterns further illustrates the evolution of Tibetan dwellings. Traditional houses (Houses 1-7) exhibit strong connections between key spaces, such as S-LR and K-OT, emphasizing their agricultural and communal focus. Contemporary houses (Houses 8-10) retain some traditional patterns while shifting toward corridor-dominated layouts, with connections like C-LR and C-H reflecting the growing importance of circulation spaces. In modern houses (Houses 11-12), traditional patterns have largely disappeared, replaced by strong connections between corridors and main functional spaces, along with increased connectivity between outer yards (Yo) and auxiliary spaces. These changes highlight a transition from agrarian-oriented spatial configurations to circulation-centric layouts, driven by modernization and changing socio-cultural priorities.

A relevant study on Tibetan vernacular dwellings using JPG method is the one conducted by An et al.26. This paper analyzes Tibetan vernacular dwellings in semi-agricultural and semi-pastoral transition zone in Gannan Prefecture and reveals the variability of vernacular dwellings in different areas within Tibetan settlements, influenced by the varying intensity of Han cultural diffusion26. Similarly, Ganzi County, is also a semi-agricultural and semi-pastoral transition zone. As a key hub in northern Kham, Ganzi County has historically experienced frequent inter-ethnic interactions, with notable influences from Han-style courtyard dwellings. Furthermore, with urbanization and tourism development, the spatial layouts of houses in Ganzi County are increasingly resembling modern Han rural residences. While the perspectives differ, both studies underscore the historical transformations in Tibetan spatial layouts and their influencing factors.

While the JPG method effectively highlights spatial-genotype transitions, it has notable limitations. One key issue is its disregard for spatial dimensions, as it focuses solely on topological relationships and overlooks the size or scale of spaces, which may influence their function and accessibility17,16. This reliance on quantitative metrics may also fail to capture the nuanced cultural meanings embedded in spatial arrangements. Additionally, the sample of twelve houses, though representative, may not encompass the full diversity of Tibetan dwellings in Ganzi County. Future research should integrate qualitative methods, such as ethnographic studies, to explore how spatial-genotype changes relate to broader social and cultural transformations. Expanding the dataset to include a wider range of Tibetan dwelling types and regions, combined with advanced computational techniques like machine learning, could further refine the predictive modeling of spatial-genotype changes under evolving socio-economic conditions.

Data availability

Availability of data and materials: Please contact the author for data requests.

References

Dettlaff, W. Space syntax analysis–methodology of understanding the space. PhD Interdiscip. J. 1, 283–291 (2014).

Zolfagharkhani, M. & Ostwald, M. J. The spatial structure of Yazd courtyard houses: a space syntax analysis of the topological characteristics of the courtyard. Buildings 11, 262 (2021).

Mustafa, F. A. & Hassan, A. S. Mosque layout design: an analytical study of mosque layouts in the early Ottoman period. Front. Archit. Res. 2, 445–456 (2013).

Hillier, B. Space is the machine: a configurational theory of architecture. (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996).

Griffiths, S. The use of space syntax in historical research: current practice and future possibilities. In Proc. of the 8th International Space Syntax Symposium (eds Greene, M., Reyes, J. & Castro, A.) 8193 (PUC: Santiago, Chile, 2012).

Redjem, M. & Mazouz, S. Spatial and social interaction in medieval algerian mosques: a morphological analysis using space syntax. Built Herit. 6, 55–75 (2022).

Rashid, M. Space syntax: a network-based configurational approach to studying urban morphology. In The Mathematics of Urban Morphology. 199–251 (Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2019).

Wang, M. et al. Spatial pattern and micro-location rules of tourism businesses in historic towns: a case study of Pingyao, China. J. Destin. Market. Manag. 25, 100721 (2022).

Yin, L., Wang, T. & Adeyeye, K. A comparative study of urban spatial characteristics of the capitals of tang and song dynasties based on space syntax. Urban Sci. 5, 34 (2021).

Wang, Y., Lin, D. & Huang, Z. Research on the aging-friendly kitchen based on space syntax theory[J]. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 5393 (2022).

Fallah Tafti, F. & Lee, J. H. Examining variance, flexibility, and centrality in the spatial configurations of Yazd schools: a longitudinal analysis. Buildings 12, 2080 (2022).

Xu, K., Chai, X., Jiang, R. & Chen, Y. Quantitative comparison of space syntax in regional characteristics of rural architecture: a study of traditional rural houses in Jinhua and Quzhou, China. Buildings 13, 1507 (2023).

Kim, Y., Kim, J., Yum, H. & Lee, J. A study on mega-shelter layout planning based on user behavior. Buildings 12, 1630 (2022).

Lee, J. H., Ostwald, M. J. & Dawes, M. J. Examining visitor-inhabitant relations in Palladian villas. Nexus Netw. J. 24, 315–332 (2022).

Hanson, J. Decoding homes and houses. (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999).

Hillier, B. & Hanson, J. The social logic of space. Volume 1 (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984).

Ostwald, M. J. The mathematics of spatial configuration: revisiting, revising and critiquing justified plan graph theory. Nexus Netw. J. 13, 445–470 (2011).

Ostwald, M. J. A justified plan graph analysis of the early houses (1975–1982) of Glenn Murcutt. Nexus Netw. J. 13, 737–762 (2011).

Jeong, S. K. & Ban, Y. U. The spatial configurations in South Korean apartments built between 1972 and 2000. Habitat Int. 42, 90–102 (2014).

Elizondo, L. A justified plan graph analysis of social housing in Mexico (1974–2019): spatial transformations and social implications. Nexus Netw. J. 24, 25–53 (2022).

Lee, J. H., Ostwald, M. J. & Gu, N. A justified plan graph (JPG) grammar approach to identifying spatial design patterns in an architectural style. Environ. Plan. B: Urban Anal. City Sci. 45, 67–89 (2018).

Lee, J. H. & Ostwald, M. J. Mathematical beauty and Palladian architecture: measuring and comparing visual complexity and diversity. Front. Archit. Res. 10, 467-–4482 (2021).

Dawes, M. J., Lee, J. H. & Ostwald M. J. Examining control, centrality and flexibility in Palladio’s villa plans using space syntax measurements. Front. Archit. Res. 10, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2021.02.002 (2021).

Kamelnia, H., Hanachi, P. & Moayyedi, M. Exploring the spatial structure of toon historical town courtyard houses: topological characteristics of the courtyard based on a configuration approach. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHMSD-03-2022-0051 (2022).

Asif, N., Utaberta, N., Sabil, A. B. & Ismail, S. Reflection of cultural practices on syntactical values: an introduction to the application of space syntax to vernacular Malay Architecture. Front. Archit. Res. 7, 521–529 (2018).

An, Y., Liu, L., Guo, Y., Wu, X. & Liu, P. An analysis of the isomerism of Tibetan vernacular dwellings based on space syntax: a case study of the semi-agricultural and semi-pastoral district in Gannan Prefecture, China. Buildings 13, 2501 (2023).

Manum, B., Rusten, E., & Benze, P. AGRAPH, Software for Drawing and Calculating Space Syntax Graphs. Proceedings of the 5th International Space Syntax Symposium, vol. I, 97. Delft (2005).

Manum, B. AGRAPH: Complementary software for axial-line analysis. In Proc. of the 7th International Space Syntax Symposium. (eds. Daniel Koch, Lars Marcus and Jesper Steen) (Stockholm: KTH, 2009).

Markus, T. Buildings as classifying devices. Environ. Plan. B: Plan. Des. 14, 467–484 (1987).

Peponis, J., Wineman, J., Rashid, M., Hong Kim, S. & Bana, S. On the description of shape and spatial configuration inside. Build.: Convex Partit. Their Local Prop. Environ. Plan. B 24, 761–781 (1997).

Bafna, S. The morphology of early modernist residential plans: geometry and genotypical trends in Mies Van der Rohe’s designs. Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Space Syntax, Brasilia,1999, pp. 01.01–01.12.

Bafna, S. Geometric intuitions of genotypes. Proc. of Third International Space Syntax Symposium. 7–11 May, 20.21–20 (Atlanta, 2001).

Wang, W. L., Lo, S. M. & Liu, S. B. A cognitive pedestrian behavior model for exploratory navigation: Visibility graph based heuristics approach. Simul. Model Pract. Theory 77, 350–66 (2017).

Gökçen, D., & Özbayraktar, M. Integrating space syntax and system dynamics for understanding and managing change in rural housing morphology: a case study of traditional village houses in Düzce, Türkiye. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 1–29, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-024-05132-01 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the professors, doctoral students and graduate students in Xi'an University of Architecture and Technology (XUAST) who have been involved in the study of Tibetan houses and settlements in western Sichuan, China. Special thanks to photographer Yang Yong for capturing and providing the scenic images of Ganzi County. We also extend our gratitude to the editor and each reviewer for their patience and valuable feedback, which greatly contributed to the improvement of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors designed the study. Zhe, Lei. analyzed the data and wrote the paper. All authors contributed to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lei, Z., Li, J. Genotype extraction of traditional dwellings using space syntax: a case study of Tibetan rural houses in Ganzi County, China. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 13 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01590-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01590-5

This article is cited by

-

Research on Cell-Chain-Form graphical representation and restoration of traditional architectural windows and doors

npj Heritage Science (2025)

-

Sofa as a Spatial Core: Exploring Regional Variations in Traditional Turkish House Plans Through Space Syntax

Nexus Network Journal (2025)