Abstract

The ancient Yi books have a long history and are one of the most important cultural heritages of humanity. Currently, Yi character image recognition datasets are all constructed by manual handwriting. Nevertheless, there are significant feature differences between handwritten character images and real ancient manuscript character images. This limits their effectiveness in practical ancient manuscript character recognition scenarios. To address these issues, we propose a novel dataset construction method to construct a real-world character dataset Yi_1047. Our method first uses an unsupervised contrastive learning model to perform accurate feature extraction. It applies this to a large number of unlabeled single-character images from real ancient manuscripts. Then, we use image retrieval and clustering methods to construct a real Yi script single-character dataset. It contains 1047 classes of ancient Yi script characters, totaling 265,094 character images. It is currently the only non-manually handwritten ancient Yi single-character dataset. Additionally, for highly similar characters, we specifically construct a comprehensive list of similar characters. Extensive experimental results demonstrate the effectiveness and superiority of our proposed method for constructing the Yi_1047 dataset. This innovative method not only achieves the digital preservation of ancient Yi script, but our experiments also show that it plays a role in constructing single-character recognition datasets for other ancient books.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Yi ethnic group is an ancient and mysterious ethnic group residing in the southwestern region of mainland China. As early as 10,000 years ago, ancestors of the Yi ethnic group create Yi script characters, which become one of the six major ancient scripts in the world1. The Yi ancestors create countless ancient books that document the cultural heritage and wisdom passed down through the long course of historical development. The content is extensive and voluminous, covering various aspects such as astronomy, geography, divination, medicine, etc.23. Due to its strict cultural transmission system, only specific Yi Bimo individuals possess the skills required to translate Yi language ancient books. Nevertheless, with the passage of time, the number of individuals capable of translating these books decreases. Therefore, many ancient books become treasures buried in dust4. This highlights the urgency of applying intelligent analysis and machine translation tasks to ancient Yi books. In this way, we can ensure the preservation of these valuable human cultural heritages. For the analysis and translation of ancient Yi language books, the first step is to recognize individual characters5. Currently, single-character recognition tasks achieve good recognition results in isolated languages such as handwritten Chinese. Designing neural networks with various ingenious structures becomes the most effective method for single-character recognition tasks. In this case, constructing high-quality large-scale datasets becomes the most important task.

At present, the construction of single character datasets is mainly achieved through manual handwriting imitation. For instance, Bi et al. construct a Naxi Dongba script single-character recognition dataset DB14046 by manual handwriting imitation. This dataset contains 1404 Naxi Dongba script character classes and 445,273 single-character image samples. Tang et al. use clustering and manual handwriting methods to construct a Shuishu character image dataset, ShuiNet-A7. The dataset contains 113 water character categories and a total of 226,000 water character single character image samples. Chen et al.8 construct a single-character dataset for Ancient Yi Script through artificial handwriting imitation. This dataset comprises 2142 Ancient Yi Script character categories, with ~300,000 Ancient Yi Script single-character image samples. Researchers also conduct studies on this dataset for One-shot Yi character recognition9 and Yi character image restoration10.

The above studies all construct corresponding datasets through handwriting. Although they can perform well in handwritten data recognition, they are limited by feature differences in practical ancient book application scenarios. Participants lack expertise in ancient books, which leads to significant differences between handwritten single-character images and real ancient book single-character images. In addition, different writing tools produce inconsistent results. For instance, ancient books are typically written with brushes or carving tools, whereas manual imitation often employs finer tools like ballpoint pens. The specific example is shown in Fig. 1. One can see that the strokes of the characters in the first row are curved in real ancient book images, but in the artificially imitated images, they are depicted as vertical. The remaining lines of text exhibit similar issues. In addition, the tools used by the imitators are mostly ballpoint pens, which produce thinner strokes compared to those found in real ancient book images. This difference significantly affects the extraction of single-character image features.

As mentioned above, despite their outstanding performance in handwritten Yi script single-character recognition, they fall short when it comes to recognizing single characters in ancient Yi script books. This phenomenon can be attributed to the limitations of writing experience and writing tools. These limitations restrict the development of single-character recognition tasks for real ancient Yi script books. Therefore, it is necessary to construct a single character image dataset from real Yi ancient books. Due to the lack of single image labels, we first use unsupervised contrastive learning to enable the model to extract features from single-character images in ancient Yi script manuscripts. Subsequently, we use clustering and image retrieval methods to construct a real single-character image dataset of ancient Yi books.

In the dataset construction process, we find that the character frequency in ancient Yi script manuscripts exhibits a long-tail distribution. Therefore, to better explore unsupervised feature extraction models, we also construct a novel long-tail dataset. Finally, to validate the effectiveness of our method, we also conduct extensive experiments on Shuishu and ancient books. The contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

1.

We propose a general method for constructing real ancient books datasets. First, unsupervised contrastive learning is utilized to extract features from a large amount of unlabeled data. Then, clustering and bidirectional are combined to complete the dataset construction process. Experiments demonstrate that this method extends to the construction of single-character recognition datasets for other isolated languages, such as Shuishu and Classical Chinese.

-

2.

We construct a real ancient Yi script single-character dataset, comprising 1047 categories and 265,094 character image samples. It is the largest authentic dataset for ancient Yi character recognition.

-

3.

We create a long-tail data dataset and a list of similar characters. The similar character list is used to further improve the recognition of individual characters in ancient Yi manuscripts. The long-tail dataset trains the unsupervised model to extract features tailored for long-tail data.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In “Related work”, we introduce similar single-character recognition datasets and existing Yi script single-character datasets. “Methodology” provides a detailed description of our dataset construction methods. “Experiments” describes the experimental settings, experimental results, and the dataset itself. Finally, “Conclusions” closes with a summary.

Related work

Currently, most single-character recognition datasets are constructed through manually imitating handwriting. Only a small portion is created using clustering methods11, but these datasets are often relatively small in scale. This section will provide a detailed overview of the existing single-character recognition datasets, as well as the Yi script single-character recognition datasets. Finally, we introduce existing methods for constructing datasets using clustering, self-labeling, and other techniques.

Single-character image datasets

With the development of pattern recognition and deep learning, researchers construct several public datasets to address problems such as image classification and single-character recognition. For the recognition tasks of digits and English letters, Peter et al. create the NIST handwritten dataset12. NIST contains 62 classes of characters, including lowercase English letters a-z, uppercase English letters A-Z, and digits 0-9. It involves 3600 volunteers, with each character category having over 2000 samples on average. The digit category has the highest number of samples, with the most numerous category exceeding 40,000 samples. It advances the field of digit and English character recognition. For Chinese character recognition tasks, Liu et al.13 construct the CASIA-HWDB dataset. It contains 7185 classes of Chinese characters with a total of 3,721,874 character samples. The large number of categories and samples presents a more challenging task for single-character recognition models. The above two datasets greatly propel the development of Chinese, English, and numeric single-character recognition tasks, making significant contributions to the advancement of this field. It ensures the diversity of the samples, meeting the practical application requirements.

In addition to single-character images of currently used character, many researchers construct various datasets of single-character images from ancient books. These characters are no longer used by people today. Inspired by the construction of single-character recognition datasets for currently used scripts, many ancient single-character datasets are also created using handwritten methods. Among these datasets, Tang et al. release the Shuishu single-character recognition dataset shuishu_C7. First, they crop single-character images from ancient books and then manually label the cropped single-character images. Since the samples are directly cropped from ancient books, the number of samples in each category is influenced by the frequency of characters in those books. For categories with fewer samples, Tang et al. expand the dataset through handwritten imitation and data augmentation. They ultimately construct a dataset comprising 113 categories with a total of 226,000 sample images.

Unlike the construction method of Shuishu_C, Bi et al. refer to the current dataset construction methods used for characters. They create the Dongba single-character dataset DB14046 entirely through handwritten means. It contains 1404 categories with a total of 445,000 samples, making it one of the largest publicly available Dongba single-character recognition datasets. The construction method of the aforementioned dataset is very similar to the construction method of existing datasets for the recognition of ancient Yi characters. They all construct single-character recognition datasets either entirely through handwritten methods or by partially supplementing with handwritten samples. “The Yi script single-character image dataset” provides a detailed discussion on constructing a dataset through manual handwriting.

The Yi script single-character image dataset

The Yi character set has a very large number of categories, making its construction more challenging compared to other ancient single-character datasets. Currently, there are over ten thousand volumes of ancient Yi books in existence, and when including those scattered among the people, the total number can reach tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of volumes. They record the centuries-old history and culture of the Yi people, making them an important part of humanity’s cultural heritage.

Currently, there are three known datasets for Yi single-character recognition, constructed using various methodologies such as clustering, manual annotation, and artificial imitation. Jia et al. collect Yi ancient book images and segment them into 50,000 Yi single-character images11. These character images are not labeled with specific categories. Subsequently, they use a clustering algorithm that recognizes density peaks to cluster these 50,000 images into 100 categories. Then, they select the correct category sample images from these 100 categories and finally obtain a dataset containing 10,530 Yi character image samples. This method uses clustering to classify unlabeled images and construct the dataset. Nonetheless, due to the insufficient high-level semantic features, it can only cluster them into 100 categories. This does not meet practical application needs.

To solve the problem of few categories of Yi characters, Chen et al. construct a handwritten Yi character dataset through artificial imitation. This dataset addresses the issues of insufficient character categories and limited sample size in Yi datasets8. They distribute handwritten character collection sheets containing commonly used ancient Yi characters to 120 volunteers, with a total of 1200 copies distributed. This effort collects 2142 categories of Yi script characters, totaling 151,200 Yi script single-character image samples. This dataset is also the largest to date in terms of both categories and sample size for Yi script single characters. Unlike datasets constructed entirely through handwritten methods, Shao et al. create their dataset using two types of sample images: one through artificial imitation and the other from screenshots of manually annotated book. This dataset comprises a total of 1130 Yi script character classes and 78,042 Yi script image samples. These two datasets successfully fill the gap in Yi script single-character recognition datasets and make a significant contribution to the digital preservation of Yi script ancient books.

Nevertheless, they are primarily constructed through artificial imitation, which presents the same issues as the other ancient single-character image datasets. Since the writers are not familiar with the ancient characters they are imitating, the handwritten images exhibit significantly different characteristics from the single-character images found in authentic Yi ancient books. Although it performs well in handwritten single-character recognition, its effectiveness in recognizing single characters in actual ancient books still needs further improvement. The dataset we construct complements the above dataset in the field of ancient Yi character recognition. In addition, the construction of handwritten datasets requires a large number of participants. Specifically, CASIA-HWDB1.0-1.2 involves 1020 volunteers in its construction, and HWAYI involves 120 volunteers in the imitation work.

Unlike the methods, which require a large amount of manual work, our dataset construction method can significantly reduce the amount of manual work. It not only improves the recognition accuracy of single characters in authentic ancient books, but also enhances the efficiency of dataset construction.

Existing dataset construction methods

Currently, most datasets rely on manual annotation for their construction. Only a few studies use clustering algorithms to construct datasets, and a small number of unsupervised approaches validate the self-annotation performance of models on existing datasets. For instance, Jia et al.11 apply a clustering algorithm based on finding density peaks to classify 50,000 Yi script single-character images. After filtering, they create a handwritten Yi script single-character dataset containing 100 classes with 10,530 image samples. This method takes raw images as input or uses compressed features from PCA or SVD for clustering. Due to insufficient extracted features, it can only cluster a limited number of categories and samples, making the constructed datasets unsuitable for practical applications. Recently, the advanced semantic feature extraction capability of deep learning models gains widespread attention from researchers. It achieves remarkable results in fields such as image classification, object detection, and image segmentation. Nonetheless, the model training requires a large amount of manually annotated data for supervised training, which contradicts our research on dataset construction. With the development of unsupervised contrastive learning techniques14,15,16,17,18, deep learning models can accurately extract advanced semantic features from images in an unsupervised manner. This development enables deep learning models to accurately extract semantic features from images in the absence of image labels. These extracted features can be used for clustering or image retrieval, thereby automatically constructing datasets. Nonetheless, most contrastive learning models require a large number of negative samples for comparison with positive samples. This leads to high GPU memory space requirements for training machines15,19,20.

Currently, most unsupervised image self-labeling tasks are applied to natural image datasets such as ImageNet21 and CIFAR1022. Nevertheless, this technology is not widely applied to single-character datasets at present. In natural image datasets, Wouter et al.23 employs three steps—unsupervised feature extraction, nearest neighbor mining, and fine-tuning self-labeling—to accomplish image category self-labeling tasks. Elad et al.24 proposes an end-to-end self-labeling model that enhances self-labeling effectiveness through a mathematically motivated variant of the cross-entropy loss. The self-labeling method mentioned above assigns a unique label to all unlabeled samples and requires prior knowledge of the number of classes in the dataset. In the actual task of constructing a single-character image dataset, we cannot determine the number of categories for the unlabeled image samples. Similarly, we do not need to classify all the unlabeled samples. We only need to provide a sufficient number of training, validation, and testing samples for each category. Therefore, our research proposes to construct a Yi character recognition dataset using image retrieval and clustering methods, rather than traditional self-annotation approaches.

Methodology

In this section, we first introduce the sample collection process of the dataset. Then, we describe the proposed dataset construction method, including the feature extraction process based on unsupervised contrastive learning, image retrieval, and image clustering. Finally, we provide a detailed description of the constructed dataset, including the list of similar characters and the long-tail dataset.

Data collection

We directly choose to segment from authoritative translations and annotations of ancient books, thereby obtaining authentic Yi script single-character images. This solves the problem of significant differences between artificially imitated handwriting and the actual characteristics of single characters in ancient books. The main data source is the authoritative translation of the “Southwest Yi Zhi”25 known as the encyclopedia of the Yi people. It is the most voluminous and content-rich historical work in Yi script, comprising a total of 26 volumes and over 370,000 characters. It is an important historical record for studying the ancient astronomy, politics, military, religion, culture and other aspects of the nation.

The specific construction process is as follows: First, we scan Yi script books to obtain digitized images. Then, we binarize the digitized images and apply row projection to obtain single-line images. These operations can generate a large number of unlabeled single-character images. This completes the collection of authentic single-character image samples of ancient Yi script.

Research framework and methods

Through the collection, we obtain a large number of unlabeled Yi script single-character image samples. Then, we use a two-stage dataset construction method to automatically label the above samples. In the first stage, we apply unsupervised training to the Fine-tunes Prototypical contrastive learning model26. The training data is a large amount of unlabeled single-character data collected during the data collection phase. This allows the backbone network to accurately extract high-level semantic features from single-character images. In our framework, we select ResNet50 as the backbone.

In the second stage, we employ a bidirectional retrieval method. We select the k most similar images for each chosen image from the large unlabeled dataset. The value of k is manually set according to actual needs. Thus, we can select the required images to form the single-character recognition dataset. In addition to constructing the single-character recognition dataset, we also use clustering methods to build a long-tail dataset of Yi script single-character images. Finally, we complete the dataset construction by manually filtering out incorrect samples. The process of dataset construction is illustrated in Fig. 2.

First, we use our fine-tuned PCL model to perform unsupervised feature extraction on a large number of unlabeled images. It automatically extracts image features through contrastive learning of positive and negative examples. At the same time, it uses the K-means clustering method to adjust the category semantic space, enabling the model to better extract category semantic features. The trained model extracts features from unlabeled images, followed by bidirectional image retrieval and clustering tasks, ultimately completing the dataset construction.

Unsupervised feature extraction

The dataset construction process is essentially labeling a portion of the large unlabeled data. This requires extracting high-level semantic features from single-character images. Then, we use methods such as clustering, image retrieval, or self-labeling for the labeling process. In terms of feature extraction, deep learning models achieve significant advantages over traditional methods like PCA and SVD on multiple public datasets. However, most early deep learning models require supervised learning during training. This training method contradicts the original intention of constructing the dataset. Therefore, we need to use an unsupervised training method, which allows the model to be trained on large unlabeled datasets. At present, common unsupervised learning methods include Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)27,28, Autoencoders29, and Contrastive learning. Unsupervised generative learning methods14 such as GANs and autoencoders primarily focus on reconstructing image content. They do not focus on extracting high-level semantic features like categories. On the other hand, contrastive learning evaluates whether two images belong to the same category by using positive and negative samples. This approach is more suitable for category classification tasks and aligns with the research requirements for constructing dataset clusters. Since we need to differentiate the category semantic features of the samples, we choose the contrastive learning method to extract unsupervised features from unlabeled images. The contrastive learning method is mainly implemented through the contrastive learning loss function. The loss function is represented by Equation 114.

In Equation 1, n represents the number of samples, r represents the number of negative samples, vi and \({v}_{i}^{{\prime} }\) are the features of two positive samples from different views of the same sample, vj is the feature of a negative sample, and τ is the temperature coefficient.

We choose the Fine-tunes contrastive learning model PCL for feature extraction. The model uses a standard encoder for feature encoding of positive samples at the beginning of training. Meanwhile, it uses a momentum encoder for feature encoding of negative samples. The negative sample features extracted by the momentum encoder continuously update the momentum feature queue after each iteration. We choose ResNet-50 as the standard encoder and momentum encoder, with the specific network structure shown in Table 1.

After the number of iterations exceeds the preset warm step, a clustering algorithm is used to optimize the distribution of samples in the feature space. At the same time, the EM algorithm is used for iterative optimization. It is important to note that the clustering algorithm is used after each training iteration is completed. This follows the completion of feature extraction for all training data using the standard encoder. The loss function \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\rm{info}}}\text{NCE}\,\) is shown in Equation 2. We fine-tunes settings such as the number of clusters, momentum feature queue length, and batch size based on the characteristics of the data. The model’s overall training framework is illustrated in Fig. 3.

In Equation 2, N represents the number of samples. \({c}_{s}^{m}\) is the cluster center for the category of positive samples, and \({\phi }_{s}^{m}\) is the density of the cluster samples corresponding to this category. \({c}_{s}^{j}\) is the cluster center for the category of negative samples, and \({\phi }_{s}^{j}\) is the density of clustering samples in the corresponding category.

This model adopts MOCO’s momentum queue mechanism, which enables it to dynamically store and update negative samples. The momentum queue ensures that the features of negative samples in the queue continuously update while it maintains the number of negative samples. The aforementioned setup ensures feature consistency between positive and negative samples during the contrastive learning process. Furthermore, the model enhances its ability to extract high-level semantic features from categories by using clustering techniques after each training iteration. This reduces the distance between features of the same category in the feature space and increases the distance between features of different categories. This distribution of the feature space provides more accurate category semantic features for subsequent image retrieval tasks. The loss function is represented by Equation 2. The detailed proof is presented in ref. 26.

Bidirectional image retrieval and clustering

The construction of the dataset only requires retrieving a certain number of sample images for each class from the unlabeled data. This requirement is sufficient to meet the needs of dataset construction. There is no need to assign labels to each unlabeled data as in the traditional category self-labeling process. Therefore, we avoid using self-labeling methods to assign labels to the categories. Instead, we use a retrieval-based method to construct the Yi script single-character dataset.

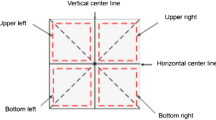

For most image retrieval methods, the standard procedure includes selecting a representative sample from each category and querying it within the specified database. We calculate the feature distances and select a predetermined number of sample images based on these distances. These sample images belong to the same category as the query sample. It is worth noting that during retrieval, we first need to construct a directory list of Yi script character categories, with each category containing a sample image as a retrieval template. If we use standard retrieval methods, we will overlook the valuable information in the directory list. Therefore, we innovatively propose a bidirectional image retrieval method based on the requirements of data set construction. In addition to selecting a specific category sample for retrieval in the unlabeled database, the method also compares each sample in the unlabeled database with the samples in the directory list. The specific process is illustrated in Fig. 4. We first select the top-K samples with the closest feature distances for each retrieved category sample from the unlabeled samples. Then, we select the top-H most similar categories for each unlabeled sample. Two retrieval lists are obtained through the aforementioned two retrievals. Finally, we generate a selection retrieval matrix from the two retrieval lists, which eliminates a large number of incorrect retrieval samples. It then filters out the Top N most similar samples from the directory list for each unlabeled sample. The method effectively utilizes the informational advantages of the Yi script sample directory list. This significantly improves the accuracy of image retrieval and, in turn, enhances the efficiency of dataset construction. In “The effectiveness of bidirectional image retrievals”, we validate the effectiveness of the method on publicly available large-scale Chinese datasets. The experimental results show that the accuracy of retrieval significantly improves after performing bidirectional retrieval.

The left side of the image identifies the top-H most similar Yi script categories for all M unannotated images and generates a similarity matrix with dimensions M × N. The right side identifies the top-K most similar samples for all N Yi script categories, with a matrix size of N × K. The center of the image displays the selection matrix generated from the similarity matrices produced by the two retrievals.

In addition to its application in dataset construction tasks, image retrieval involves the following two aspects: 1. Add new Yi script categories to the dataset. During the dataset construction process, it is first necessary to build a directory of Yi script character categories. This directory is used to determine whether the encountered Yi script categories are already included in the directory. Therefore, we need to select a template image sample in advance for each category in the directory for retrieval purposes. In the absence of a dictionary, manual comparison retrieval can be very slow. Therefore, we use image retrieval methods to continually insert new category samples by continuously comparing new samples with existing categories. 2. Construct a list of similar characters. In addition to constructing a conventional Yi character dataset, we also notice that the recognition performance of similar characters is worse than that of other categories through observation of experimental results. To address this issue, we need to create a list of similar Yi characters. During the construction process, we select all similar characters based on the retrieval results and complete the creation of the list of similar characters. This list contributes to improving the recognition results of Yi script single characters, particularly by providing data support for better recognition of similar characters.

Currently, unsupervised feature extraction for long-tail data is still inferior compared to normally distributed data. However, there are currently few character image datasets available with long-tail distribution characteristics. In addition, the long-tail distribution in ancient books is more uneven compared to that in natural images. The most common categories have tens of thousands of images, while the least common categories have only one image. Therefore, we not only construct a Yi script character recognition dataset and a list of similar Yi characters. We also create a long-tail recognition dataset based on the long-tail distribution of characters in ancient books. During the dataset construction process, we choose the efficient K-Means algorithm for clustering. This is applied to the Yi script single-character image features extracted by the unsupervised feature extraction model Fine-tunes PCL. After clustering, manual screening is performed to complete the construction of a long-tail recognition dataset for ancient Yi character images through the above process.

Dataset description

Yi_1047 includes a large number of Yi script characters annotated with their respective categories. It consists of three parts: Yi character recognition dataset, similar characters list, and long-tail recognition dataset. All the images contained in the dataset are cropped from real ancient manuscripts and their translations. The Yi character recognition dataset is used for training and validating models for single character recognition in ancient Yi books. The list of similar characters is specifically used for training and validating the recognition of similar characters to improve the accuracy of Yi character recognition. The long-tail recognition dataset is used for training and validating models for unsupervised feature extraction and clustering of long-tail character data.

Yi character recognition dataset

The Yi character recognition dataset is constructed through image retrieval and is used for the task of recognizing ancient Yi characters. It includes as many categories and samples of ancient Yi characters as possible. This enables deep learning models to better learn the high-level semantic features of single character image samples, thus achieving better performance in single character recognition and OCR tasks for ancient Yi books. The Yi character recognition dataset constructed in this study contains 69,389 samples, distributed across 779 categories. All categories in this dataset contain more than 20 samples, and each character is cropped from real ancient manuscripts and their translations. We assign a unique code to each category, consisting of letters and numbers. Due to the differences in the shape of each sample character, the width and height of all images range between 70 and 100. The images generally appear square. The display of some single-character categories and their codes is shown in Fig. 5.

List of similar Yi characters

The list of similar characters is constructed through image retrieval and is specifically used for similar character recognition tasks. Presently, handwritten single-character recognition for languages like Chinese, ancient Yi script, and Shuishu script achieves very high accuracy. Nonetheless, the recognition of similar characters does not receive much attention, yet it becomes a critical factor limiting further improvements in recognition rates. We conducted extensive ablation experiments to investigate this issue (described in “The effectiveness of the single-character recognition dataset”). The results confirmed that several classical models have lower accuracy in recognizing similar characters compared to single character recognition in other categories. At present, there is no dataset specifically designed for studying similar characters in ancient Yi script. Therefore, we address this issue by constructing a list of similar characters in ancient Yi script. The list is specifically aimed at the task of recognizing similar characters in ancient Yi script. It can further enhance the model’s ability to extract local detail features and provide a data foundation for training and testing similar character models. The list of similar characters contains 67 similar character groups, with each group containing between 2 and 10 categories. The categories within each group have only subtle differences in character shape, while the overall shapes are very similar. All samples also come from real ancient manuscripts and their translations. The size and code are the same as those described in “Yi character recognition dataset”. Specific examples can be seen in Fig. 6. The list of similar characters in ancient Yi script constructed in this study contains 187 categories.

Ancient Yi script long-tail dataset

The dataset is constructed through clustering and addresses issues related to unsupervised feature extraction and recognition for long-tail data distributions. Due to the differences in the frequency characters in real ancient books, the distribution characters exhibits a long-tail pattern. This means that some characters in the head of the distribution may appear thousands of times, while other characters in the tail appear infrequently, sometimes even only a few times. The proposed dataset construction method involves model training, clustering, and image retrieval for long-tail data. Due to the lack of long-tail data sets, we directly use classic models to perform advanced feature extraction and clustering on Yi character images. Since the models are not tailored for long-tail data processing, the feature extraction results and clustering effectiveness will be greatly affected. This greatly affects the effectiveness of dataset construction. Therefore, we address the above issue through multiple iterations of clustering, ultimately constructing a large-scale long-tail dataset. The dataset reflects the actual distribution of Yi characters in ancient books. The specific character frequency distribution is shown in Fig. 7.

From Fig. 6, we can see that there are significant differences in frequency, with some frequencies reaching only twenty thousand times, and others only occurring once. Other researchers can explore contrastive learning models, clustering methods, and other research areas suited to long-tail data distributions based on this dataset. At the same time, it can also test the performance of unsupervised feature extraction models on long-tail distribution data. This helps in constructing real ancient book single-character image datasets for other languages.

In summary, we construct a dataset of ancient Yi characters Yi_1047, which includes three parts:Yi character recognition dataset, similar character list and long-tail recognition dataset. It provide data support for various tasks such as Yi ancient character recognition, OCR (optical character recognition), and character database construction, etc. At the same time, to address the issue of low accuracy in recognizing similar characters, we specifically construct a list of similar Yi characters. Additionally, we also create a long-tail data recognition dataset.

Experiments

In the dataset construction section, the feature extraction model and bidirectional image retrieval model for dataset construction were implemented using the PyTorch framework. Details about the dataset can be found in “Methodology”. All images are resized to 100 × 100 pixels. The learning rate is set to 0.03. The SGD optimizer is adopted for parameter updates. In the unsupervised feature extraction phase, the epoch is set to 200. The batch size is set to 256. The feature dimension extracted by the last layer of the model is set to 128. The queue size of negative pairs is set to 1024, which is the number of negative samples required in contrastive learning. In the image retrieval phase, Top-H is set to 5, and Top-K is set to 150. In the image clustering phase, we directly use the FAISS library for image clustering. The data feature dimension is set to 128, the number of clusters to 2000, the clustering iterations to 20. We set the maximum retries to 5 in case of clustering failure. The maximum number of items per cluster is 1000, with a minimum of 10. All experiments are conducted on an Ubuntu 20.04.6 LTS operating system, which includes 2 Intel(R) Xeon(R) Platinum 8358 CPUs and 8 NVIDIA A800-SXM4-80GB GPUs.

In the dataset validation section, all codes are implemented in Python using the PyTorch toolbox. We adopt 8 classical models for recognition experiments on the dataset: AlexNet, MobileNet_v2, SqueezeNet_v1, VGG16, EfficientNet_b0, ResNet50, Inception_v3, and ShuffleNet_v2. The learning rate is set to 0.01, the loss function is the cross-entropy function, and the SGD optimizer is adopted for parameter updates. The server setup matches the one described in the dataset construction section.

The effectiveness of the single-character recognition dataset

This section uses 8 classical deep learning models to validate the effectiveness of the Yi ancient single-character recognition dataset. The specific experimental results are shown in Table 2. The experiments show that after training, all models achieve a top-1 accuracy of over 93%, which demonstrates the dataset’s effectiveness.

These models include both lightweight and deep models. We adopt various evaluation metrics, such as top-1 accuracy, top-5 accuracy, recall, mAP, and F1 score, to demonstrate the recognition performance. The model with the fewest parameters, SqueezeNet, contains only 1 million parameters and achieves a top-1 accuracy of 93.99%. This result shows that even with a low number of model parameters, the model can effectively recognize ancient Yi single-character images by training on the constructed dataset. The best-performing model is MobileNet v2, which has over 3 million parameters and achieves a top-1 accuracy of 95.43%. This indicates that as the number of parameters increases, the recognition effect can be further improved. This signifies that there is still potential for deeper exploration and utilization of the dataset. It is worth mentioning that this experiment does not use any data augmentation techniques. Through observation of the experimental results, we notice that there are a large number of similar characters. This may lead to the model being unable to effectively distinguish them. Therefore, in “High-similarity character list”, we specifically discuss the recognition of similar characters. The experimental results show a significant drop in accuracy for similar character recognition compared to other single-character recognition tasks. This suggests a new direction for future research.

High-similarity character list

This section uses the same 8 classical deep learning models as in “The effectiveness of the single-character recognition dataset” to conduct recognition experiments on the list of similar characters. We do not retrain the model with new data. Instead, we directly extract the recognition results for similar characters from the results of the experiments in “The effectiveness of the single-character recognition dataset”. The experimental results show that, under the same parameter settings, the recognition accuracy for similar characters is lower than that for regular Yi script characters. The experimental results are shown in Table 3.

As shown in Table 3, all models experience a significant decrease in metrics such as top-1 accuracy and F1 score when recognizing similar characters. In the task of recognizing similar characters, the MobileNet v2 model performs notably. Nonetheless, despite its strong performance, the model’s top-1 accuracy is still only 88%, which represents a 7.43% decrease compared to the results in “The effectiveness of the single-character recognition dataset”. This indicates that existing models cannot effectively recognize similar characters, and there is still considerable potential for improving recognition accuracy. Therefore, this suggests that carefully constructing the list of similar characters is essential. It provides data for addressing the challenges of recognizing similar characters in subsequent research.

The effectiveness of bidirectional image retrievals

This section experiments with the bidirectional image retrieval algorithm used in the dataset construction process to verify its effectiveness. Since we use this algorithm to create our dataset, we conduct the experiments on public datasets for fairness. Due to the large number of Yi script characters and the substantial data volume, we choose the HW1.013 and HW1.213 datasets for the experiments. These two datasets are handwritten character datasets, with each dataset containing up to 3886 sample classes for training and testing. For feature extraction, we adopt the classic machine learning algorithm PCA and the ResNet50 model with random parameters. We also use the MOCOv2 and PCL models, with the latter combining clustering and the EM optimization algorithm. We choose ResNet50 as the backbone network. We first perform unsupervised feature extraction pre-training on the model using the training dataset, and then use the trained ResNet50 model for image retrieval. In this experiment, the retrieval quantity k for each category is 100. The experimental results show that, compared to standard image retrieval, bidirectional image retrieval reduces incorrect options and improves accuracy. The experimental results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4 shows that both the MOCO and PCL models achieve lower accuracy with standard image retrieval compared to bidirectional retrieval on the HW1.0 and HW1.2 datasets. As mentioned in “Yi character recognition dataset”, the fine-tuned PCL model introduces a clustering algorithm compared to the MOCO model. The algorithm brings features of the same category closer within the category semantic feature space. At the same time, it increases the distance between features of different categories. Therefore, the PCL model performs better than the MOCO model on both datasets. The classic machine learning algorithm PCA essentially loses its feature extraction capability when dealing with large-scale datasets, leading to suboptimal image retrieval results. In contrast, using the ResNet50 model with random parameters significantly improves image retrieval accuracy compared to the PCA algorithm. This shows that the deep learning model is highly capable. Even without training, it extracts image features more effectively than machine learning algorithms when handling large-scale datasets. On the HW1.2 dataset, the fine-tuned PCL model achieves an accuracy of 64.01% with bidirectional image retrieval. In comparison, standard unidirectional retrieval achieves only 48.00%, resulting in an improvement of 16.01%. We also observe an interesting phenomenon on the HW_1.2 dataset. Through experiments, we observe that with a similar number of correct retrievals, bidirectional retrieval significantly reduces the total number of retrievals. This improves retrieval accuracy, thereby enhancing the efficiency of dataset construction.

The method generality experiments

To demonstrate the generality of our method, we conduct unsupervised image retrieval experiments across four datasets. These include the Shuishu dataset, a real Classical Chinese single-character dataset, and a handwritten Chinese character dataset. Shuishu dataset contains 1525 classes of Shuishu characters, with a total of 152,776 character images. The real Classical Chinese single-character dataset CASIA-AHCDB Style1 Basic includes 2362 classes of Classical Chinese characters, with a total of 726,647 character images. The handwritten Chinese character datasets (HW1.0, HW1.2) are the same as the dataset used in “The effectiveness of bidirectional image retrievals”. The four datasets selected for this section’s experiments include a wide variety of characters and a large number of images, with the HW1.0 dataset containing over 1.6 million images. Moreover, this section’s tests include datasets of both handwritten characters and real ancient book images. The CASIA-AHCDB Style1 Basic dataset consists of Classical Chinese character images segmented from real Siku Quanshu ancient books, with significant variations in characteristics. The experimental results are shown in Table 5.

Nonetheless, the experimental results show that despite the complex and diverse dataset, our method maintains a retrieval accuracy of over 40%. This roughly meets the retrieval requirements for dataset construction. Therefore, it verifies that the method proposed in this paper can be used for constructing single-character recognition datasets in other languages.

To better demonstrate why we use unsupervised contrastive learning for feature extraction, we visualize the distribution of feature samples. We randomly select 8 categories, each containing 15 samples. We first apply k-means clustering and then use t-SNE to display the feature space distribution. This visualization demonstrates that after using the PCL model for feature extraction, samples from the same category cluster more closely in the feature space. The visualization results are shown in Fig. 8.

In Fig. 8, we reduce the dimensionality of sample features and use two t-SNE features to visualize the feature space distribution. From Fig. 8, we observe that before using the PCL model for feature extraction, each category’s feature distribution is relatively dispersed. This phenomenon makes it difficult to distinguish between categories. After using the PCL model for feature extraction, the feature points of each category become more concentrated in the feature space. Therefore, we can better perform category retrieval and clustering of the samples. This also demonstrates that using the unsupervised contrastive learning model for feature extraction contributes to dataset construction.

Conclusions

In this paper, we propose a novel dataset construction method to construct a real single-character dataset Yi_1047 from ancient Yi books. This dataset includes 1047 classes of ancient Yi characters and contains a total of 265,094 Yi single-character samples. Besides, we also construct a list of similar characters to better explore the model construction. Furthermore, to enable the unsupervised model to better extract semantic features from less frequently occurring data in long-tail distributions, we create a long-tail dataset. Finally, we validate the effectiveness and advancement of our proposed dataset construction method and the dataset itself through experiments. In the future, we build single-character recognition datasets for other scripts based on the methods presented in this paper to better preserve the ancient cultural heritage of various ethnic groups. We build Yi_1047 that include most of the common characters from Yi script ancient books. Nevertheless, some other Yi script ancient books still scatter among private collectors and museums, such as the National Ethnic Library and the Shexiang Museum. In the future, we strive to collect more Yi script ancient books to expand our dataset, thereby better exploring the history and culture of the Yi ethnic group.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Gu, W. Reconstructing Yi history. in Perspectives on the Yi of Southwest China Vol. 26, 21 (University of California Press, 2001).

Bao, H. & Bao, A. The current situation of collection and research on ancient books of Chinese ethnic minorities. Inn Mongolia Soc Sci 6, 9–14 (2004).

Jinwei, M. To Study the Origin and Development of the Written Language of Yi People. Ph.D. thesis, Southwest University (2010).

Zhang, F. et al. Pay attention to the preservation status of ancient Yi books in China. China’s Ethnic Groups. 10, 65 (2005).

Lu, Y.-p, Wu, X. & Huang, W.-h. The digital construction of documents in Yi language ancient books of northwestern Guizhou. J. Guizhou Univ. Eng. Sci. 28, 18–22 (2010).

Luo, Y., Sun, Y. & Bi, X. Multiple attentional aggregation network for handwritten dongba character recognition. Expert Syst. Appl. 213, 118865 (2023).

Zhao, H., Chu, H., Zhang, Y. & Jia, Y. Improvement of ancient shui character recognition model based on convolutional neural network. IEEE Access 8, 33080–33087 (2020).

Chen, S., Han, X., Wang, X. & Ma, H. A recognition method of ancient Yi script based on deep learning. Int. J. Comput. Inf. Eng. 13, 504–511 (2019).

Liu, X. et al. One shot ancient character recognition with Siamese similarity network. Sci. Rep. 12, 14820 (2022).

Chen, S., Yang, Y., Liu, X. & Zhu, S. Dual discriminator gan: Restoring ancient Yi characters. Trans. Asian Low. Resour. Lang. Inf. Process. 21, 1–23 (2022).

Xiaodong, J., Wendong, G. & Jie, Y. Handwritten Yi character recognition with density-based clustering algorithm and convolutional neural network. In 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computational Science and Engineering (CSE) and IEEE International Conference on Embedded and Ubiquitous Computing (EUC) Vol. 1, 337–341 (IEEE, 2017).

LeCun, Y., Bottou, L., Bengio, Y. & Hafner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE, vol. 86, pp. 2278–2324 (IEEE, 1998).

Liu, C.-L., Yin, F., Wang, D.-H. & Wang, Q.-F. Casia online and offline Chinese handwriting databases. In 2011 International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition 37–41 (IEEE, 2011).

He, K., Fan, H., Wu, Y., Xie, S. & Girshick, R. Momentum contrast for unsupervised visual representation learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition 9729–9738 (IEEE, 2020).

Chen, T., Kornblith, S., Norouzi, M. & Hinton, G. A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. In International Conference on Machine Learning 1597–1607 (PMLR, 2020).

Grill, J.-B. et al. Bootstrap your own latent—a new approach to self-supervised learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 21271–21284 (2020).

Caron, M. et al. Unsupervised learning of visual features by contrasting cluster assignments. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 9912–9924 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Contrastive clustering. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence Vol. 35, 8547–8555 (AAAI Press, 2021).

Oquab, M. et al. DINOv2: Learning Robust Visual Features without Supervision. In Transactions on Machine Learning Research 2835–8856 (TMLR, 2024).

Caron, M. et al. Emerging properties in self-supervised vision transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision 9650–9660 (IEEE, 2021).

Russakovsky, O. et al. Imagenet large scale visual recognition challenge. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 115, 211–252 (2015).

Krizhevsky, A. & Hinton, G. Learning multiple layers of features from tiny images. https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~kriz/learning-features-2009-TR.pdf (University of Toronto, 2009).

Van Gansbeke, W., Vandenhende, S., Georgoulis, S., Proesmans, M. & Van Gool, L. Scan: learning to classify images without labels. In European Conference on Computer Vision 268–285 (Springer, 2020).

Amrani, E., Karlinsky, L. & Bronstein, A. Self-supervised classification network. In European Conference on Computer Vision 116–132 (Springer, 2022).

Wang, J. Qu, S. Southwest Yi zhi (Guizhou Ethnic Publishing House, 2015).

Li, J. Zhou, P. Xiong, C. Hoi, S. Prototypical contrastive learning of unsupervised representations. in Proc. 9th Int. Conf. Learn. Representations, Austria, May (2021).

Radford, A., Metz, L. & Chintala, S. Unsupervised representation learning with deep convolutional generative adversarial networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1511.06434 (2015).

Donahue, J. & Simonyan, K. Large scale adversarial representation learning. Advances in neural information processing systems 32 (2019).

He, K. et al. Masked autoencoders are scalable vision learners. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 16000–16009 (IEEE, 2022).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 60, 84–90 (2017).

Sandler, M., Howard, A., Zhu, M., Zhmoginov, A. & Chen, L.-C. Mobilenetv2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 4510–4520 (IEEE, 2018).

Iandola, F. N. et al. Squeezenet: Alexnet-level accuracy with 50x fewer parameters and <0.5 mb model size. arXiv preprint arXiv:1602.07360 (2016).

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. In: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations. San Diego, CA, USA, (2015).

Tan, M. & Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In International Conference on Machine Learning 6105–6114 (PMLR, 2019).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 770–778 (IEEE, 2016).

Szegedy, C., Vanhoucke, V., Ioffe, S., Shlens, J. & Wojna, Z. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2818–2826 (IEEE, 2016).

Ma, N., Zhang, X., Zheng, H.-T. & Sun, J. Shufflenet v2: practical guidelines for efficient CNN architecture design. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) 116–131 (Springer, 2018).

Chen, X., Fan, H., Girshick, R. & He, K. Improved baselines with momentum contrastive learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.04297 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by A. National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.62236011), B. The National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No.20&ZD279). and C. Special funding of “Young Teachers Strengthening the Awareness of the Chinese National Community” (Grant No.2024ZLQN42).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Bi Xiaojun provides ideas and guidance on the manuscript, Sun Ziwei contributes to completing the experiments and writing the manuscript, and Chen Zheng is involved in guiding the experiments and revising the manuscript. The three authors jointly participate in the revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bi, X., Sun, Z. & Chen, Z. A novel unsupervised contrastive learning framework for ancient Yi script character dataset construction. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 39 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01600-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01600-6

This article is cited by

-

Multimodal context-aware translation of the endangered dongba script

npj Heritage Science (2025)

-

Multimodal AI for Yuan Buddhist sculpture chronology and style

npj Heritage Science (2025)

-

FFSSC: a framework for discovering new classes of ancient texts based on feature fusion and semi-supervised clustering

Journal of King Saud University Computer and Information Sciences (2025)