Abstract

Historic districts, as core areas in cities rich in historical, cultural, and aesthetic resources, offer diverse tourism services to the public. The development of tourism has become a global trend in revitalizing these districts, and evaluating the tourism elements within them provides an objective and accurate basis for decision-making in their multifunctional planning. However, traditional evaluation methods often lack the precision and comprehensive coverage necessary for fine-grained, dynamic studies of tourism elements in historic districts. To address this issue, the present study proposes an evaluation model based on machine learning. Cluster analysis of comment texts is conducted through LDA topic classification, and sentiment analysis is performed using the BERT model to extract key indicators and sentiment classifications that affect tourism element evaluation. Additionally, IPA analysis is utilized to explore the relationship between the importance of tourism elements in historic districts and tourist satisfaction. The main contribution of this study is the development of a quantitative and replicable evaluation model for tourism elements, providing a scientific foundation for both tourism development and heritage preservation. The results reveal several key findings: (1) Regional function (RF) is the dominant factor in evaluating tourism elements, while tourists have a weaker perception of management and service (MS), which has the lowest weight. (2) A significant interrelationship exists among topic keywords, with historical culture, the built environment, and local characteristics being interdependent and integrated. (3) Tourism experience (TE) and historic culture (HC) received the highest positive ratings, while RF and space accessibility (SA) accounted for a greater proportion of negative feedback. (4) Despite the high importance of RF, although RF is the most important, it has a low satisfaction among tourists and is a key factor that needs to be improved. These findings deepen our understanding of key tourism elements in historic districts and offer fresh perspectives for future research on historic districts the evaluation and sustainable development of historic districts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The concept of historic districts originates from the Athens Charter, adopted by the International Congress of Modern Architecture (CIAM) in 1933. The Charter asserts that “buildings and neighborhoods of historical value should be properly preserved and not destroyed1.” The preservation of historic districts has been a critical issue in urban planning since the 20th century. Today, influenced by the value of the experience economy, tourism has become an effective means of revitalizing historic and cultural districts while fostering the tourism economy2. As an integral part of cultural heritage, historic districts are key destinations for cultural heritage tourism. However, they currently face a range of challenges, including over-exploitation of tourism resources, over-commercialization, and insufficient appeal to tourists. The root cause of these issues lies in the absence of an effective evaluation system for the tourism elements of historic districts, which could help correct the misguided direction of tourism development in a timely manner.

Tourist element evaluation refers to the objective perceptions and subjective impressions formed through the two-way interaction between people and the spatial environment of a tourist destination3. The evaluation of tourism elements in historic districts reflects their ability to introduce elements such as historical and cultural charm, tourism services, and supporting facilities to the market, generating economic benefits and social impacts. This is a crucial research topic for the revitalization of historic districts. Existing studies on this topic primarily focus on subjects such as cities4, nature reserves5, villages6, and theme parks7. As tourism in historic districts has grown, research on this topic has expanded. However, studies specifically focusing on the evaluation system of tourism elements in these districts remain scarce. Existing research also lacks a comprehensive connection to the actual experiences of tourists, creating a research gap that this study seeks to address.

The data sources for evaluating tourism elements still primarily rely on questionnaires and interviews8,9,10, which are insufficient for capturing tourists’ perceptual evaluations of tourism elements across different locations and times. Existing studies on evaluation systems have mainly employed qualitative11,12, quantitative13,14,15,16,17,18, or mixed methods19,20,21,22,23. However, each method necessitates the manual processing of large amounts of unstructured data, demanding significant human and material resources. The evaluation results for tourism elements often depend on assessments made by tourists and experts. However, this approach is subject to personal biases, leading to vague evaluation standards, and it fails to establish a genuine link between the evaluation outcomes and the feelings of the majority of tourists. As shown by the current state of research, studies on the evaluation system of tourism elements in historic districts are still imperfect. There are significant gaps in terms of research objects, data sources, evaluation indicators, and the accuracy of evaluation results, which hinder the establishment of a deep correlation between evaluation findings and tourists’ authentic experiences. Therefore, it is crucial to develop a new evaluation system for tourism elements in historic districts to comprehensively assess both the transmission of objective elements and the subjective historical and cultural perceptions of tourists. This is essential for promoting the high-quality development of tourism in historic districts.

This study proposes a machine learning-based evaluation method for tourism elements in historic neighborhoods. Machine learning algorithms possess strong generalization and self-learning capabilities, allowing them to continuously learn from large datasets and achieve self-optimization24. The study effectively integrates the topic modeling ability of the LDA model25 and the deep semantic understanding of the BERT model26 in machine learning, offering a more scientific and accurate evaluation system for the tourism elements of historic neighborhoods. The core design ideas are as follows: First, an evaluation system for tourism elements is constructed. This study leverages the rapid information collection capabilities of machine learning to gather tourists’ comments on social media about historic districts. The aim is to use review data from popular websites to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the tourism elements of historic districts, addressing the limitations of previous studies that rely on questionnaires or interviews as data sources. The evaluation indices are selected by thematically categorizing the review texts using the LDA model. Departing from the qualitative or quantitative methods used in prior research, machine learning is employed to accurately establish evaluation indicators. Second, the evaluation of each tourism element in the historic district is based on the sentiment classification of the review texts. The BERT model is used to classify the sentiments of the review texts, generating evaluation results that address the subjectivity and vague evaluation criteria found in previous studies. Finally, importance-performance analysis (IPA) is used to visually display the performance-satisfaction results of each indicator. The IPA four-quadrant diagram provides a more intuitive representation of tourists’ perceptions of the tourism elements. Specifically, this method resolves several unresolved issues in prior research:

-

(1)

In data collection and analysis, how can we overcome the time and regional limitations inherent in manual data collection?

-

(2)

In the design of evaluation indicators, what criteria should be used to screen the indicators, and how can we ensure a reasonable quantification of these indicators?

-

(3)

When scoring evaluation indicators, how can we avoid ambiguity in the standards and use machine learning methods to calculate accurate scores?

Related work

The focus of research on evaluating tourism factors

The main objects of tourism element evaluation typically include cities4, nature reserves5, villages6, theme parks7, and other destinations. For example, Naoi et al. explored the influence of city tourism brand image, positioning, and other factors on tourists’ choices through survey research4. Similarly, Zhang et al. assessed the suitability of nature reserves5, and Nedeljković et al. evaluated the development potential of rural tourism6. In comparison with the evaluation of tourism elements at other scenic spots, the evaluation objectives and focus of historic districts differ. The built environment of historic districts emphasizes the originality and integrity of historical culture and the continuity of living culture27. The tourism experience centers on cultural immersion and unique shopping opportunities, while the economic and social development highlights the local characteristics of commercial activities and the preservation of cultural heritage. The evaluation objects of historic districts mainly encompass architectural and spatial environments28,29 cultural and folklore resources4,30, and the impact of tourism on the sustainability of heritage sites31,32,33,34. For instance, Giannakopoulou et al. used a questionnaire to explore tourists’ perceptions of the value of traditional built environments29. Similarly, Weng et al. developed a system of indicators to assess the sustainability of cultural heritage tourism destinations comprehensively35. While research on the evaluation of tourism elements has become relatively mature, there remains a gap in the research on the evaluation system for tourism elements in historic districts. Given the differences in evaluation objectives and focus between historic districts and other scenic spots, it is essential to develop a specialized evaluation system for tourism elements in historic districts.

Data sources for evaluating tourism elements

The data used for evaluating tourism element indexes primarily come from two types: soft data and hard data. Soft data mainly include questionnaires or interviews8,9,10. For example, Al-Hagla et al. used two questionnaires: one to reveal Old Saida’s heritage and its attractiveness to tourists, and another to assess the impacts of cultural heritage and urban development projects from an economic perspective36. Similarly, Cetin et al. identified the problems and opportunities tourism activities may encounter by evaluating studies and literature while preserving the original characteristics of the protected area37. Hard data primarily consists of point-of-interest (POI) data38, user-generated content (UGC)39, and social media big data40. For instance, Filipe developed a tourism recommendation system based on users and points of interest (POIs)38. Jin-Soo et al. analyzed the cross-cultural destination image of Hong Kong’s top five source markets based on UGC data39, while Huahua et al. assessed tourists’ sensory experiences in space through social media data40. Currently, soft data, primarily represented by questionnaires or interviews, still dominate the field. These data are often gathered from a limited group of individuals through actual surveys or observations, making the results of sample analyses only representative of specific times and regions. Although hard data is more objective and comprehensive in evaluating tourism elements compared to soft data, its application in this field remains relatively rare.

Research methods for evaluating tourism factors

The research methods used for evaluating tourism elements are generally divided into qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods. Qualitative research methods often include techniques such as the Delphi method11 and grounded theory12. For example, Ma et al. employed the Delphi method and fuzzy mathematics to establish a cultural heritage tourism resource evaluation system11. Similarly, Li et al. analyzed online texts to assess the tourism experience of the Grand Canal Historical and Cultural Neighbourhood using grounded theory. These qualitative methods primarily rely on soft data and involve manually filtering evaluation indicators, which may be influenced by personal experience and bias, thereby compromising the objectivity of the evaluation. To address these issues, researchers began adopting quantitative methods to ensure greater objectivity in the evaluation process by using hard data. Quantitative methods commonly used include cluster analysis (CA)13 the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS)14, principal component analysis (PCA)15, structural equation modeling (SEM)16, preference ranking organization method (PROMETHEE)17, and data envelopment analysis (DEA)18. For instance, Li et al. applied the Grey Cluster Method to develop an evaluation index system for the tourism economic development level in China13. Zhang et al. used the TOPSIS method to assess the competitiveness of tourism destinations in the Yangtze River Delta region14, and Cheng et al. developed a provincial tourism development potential index model using PCA15. However, a single quantitative method may overlook complex contextual factors and causal relationships. To overcome these limitations, researchers have increasingly used a combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches, such as analytic hierarchy process (AHP)19,20,21,22 and importance-performance analysis (IPA)23. For example, Jiang et al. applied AHP to evaluate the value of six railway sites on China’s first industrial heritage list19, and IPA has been widely used in tourism satisfaction assessments, determining the importance and performance of tourism elements based on tourists’ perceptions and producing four-quadrant diagrams to assist decision-making. Variants of IPA, such as IPCA and AIPA, refine these methods by incorporating modifiers to adjust indicator weights and adjusting results by considering tourists’ attributes. For example, Boley et al. used IPA to examine residents’ perceptions of sustainable tourism initiatives23. However, both qualitative and quantitative approaches face challenges when applied to historic districts, particularly when dealing with large amounts of unstructured data. These methods struggle to fully capture the cultural heritage and emotional responses of tourists and are slow to adapt to new trends in tourism, lacking precise evaluation criteria.

In recent years, machine learning has emerged as a promising tool, and experts have started to use methods such as cluster analysis41, neural networks42, and text mining43 to study tourism elements. For example, Li et al. applied association rules to conduct cluster analysis on the preference attributes of inbound tourists at scenic spots41. Li et al. also used the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural network to predict tourism flows42. Haris et al. proposed a semantic extraction method for tourist attractions based on content analysis and natural language processing techniques43. Despite the growing use of machine learning, its application in evaluating tourism elements in historic districts remains relatively limited, particularly in terms of integrating both thematic modeling and sentiment analysis, leaving room for further innovation in this area.

Materials and methods

Overview of the study area

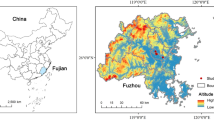

The study selects Taiping Old Street, one of the historic and cultural blocks in Changsha City, as the research object (Fig. 1). Taiping Old Street is located in the heart of the Wuyi business district in Changsha, Hunan Province, adjacent to the Xiangjiang River. Covering an area of 5.07 hectares, it is one of the best-preserved historical and cultural neighborhoods in Changsha’s ancient city. Its origins date back to the Ming and Qing dynasties, when it served as an important commercial hub and cultural exchange center. The street is lined with numerous historical buildings, featuring small green tiles, horse-head walls, and intricately carved doors and windows, which together create a distinctive architectural style. These structures embody rich historical memories and cultural heritage. This study selects Taiping Old Street as the research subject for the following reasons.

First, Taiping Old Street exhibits the typical characteristics of a historical district. It has a long history, tracing back to ancient times, and as the only historical street in Changsha preserved since the Ming and Qing Dynasties, it embodies the quintessential features of a historical neighborhood.

Second, Taiping Old Street holds significant commercial tourism value. Since its renewal and reconstruction in 2006, the street has managed to preserve its deep historical and cultural heritage while seamlessly integrating modern commercial elements. This fusion has created a unique blend where traditional culture and contemporary commerce coexist harmoniously. The area is home to a wide variety of businesses, including traditional local snack shops, souvenir stores, and handicraft shops, which collectively attract a large number of tourists.

Third, Taiping Old Street generates a substantial volume of review data on social media platforms, which can be leveraged for analysis. Changsha’s Wuyi Business District receives 30 million tourist visits annually, ranking second among the national core business districts in terms of traffic. As one of the key tourist destinations, Taiping Old Street benefits from significant foot traffic, resulting in a wealth of comment data available for analysis.

Fourth, Taiping Old Street faces several challenges common to historic districts. The sharp increase in tourist numbers has brought notable economic benefits but has also led to issues such as traffic congestion, particularly during peak seasons, which negatively impacts the visitor experience. Additionally, the area suffers from an imbalance in its functional development, with the catering industry dominating the street. There are also challenges in balancing commercial development with the preservation of historical and cultural assets. Some shop owners, in pursuit of profit, have over-decorated their establishments, and the excessive introduction of modern commercial elements has compromised the original, simple aesthetic of the historic buildings.

Currently, scholars have conducted various studies on Taiping Old Street, primarily focusing on the distribution of business forms44, quality evaluation45, and the impact of renewal and renovation46 on the neighborhood. For instance, Xu et al. investigated the community characteristics of the businesses on Taiping Old Street, analyzed the intrinsic connections between the businesses, and explored their symbiotic mechanisms44. Sun et al. employed multi-source data to assess the quality of Taiping Old Street45, while Wang et al. examined the renewal and renovation of the area to explore the potential value of the historic district in the development of a new type of urban space46. However, despite these studies, a comprehensive and scientific evaluation system for the tourism elements of Taiping Old Street remains lacking. This study seeks to address this gap by constructing a machine learning-based evaluation system to deeply analyze the tourism elements of Taiping Old Street and provide a scientific foundation for the sustainable tourism development of the historic district.

Research framework

The article presents a machine learning-based analysis method to develop an evaluation system for historic districts. The first step involves gathering research data. Using “Taiping Old Street” as the keyword, all visitor reviews from the evaluation section on the Dianping website are collected. The second step focuses on data preprocessing. The initial processing includes tasks such as removing stopwords, adding key terms, and merging synonyms to prepare the data for evaluation index selection and weight calculation. The jieba Python library is then used to further segment the text, resulting in DATE1. Subsequently, the data required for sentiment analysis are also preprocessed. Sentences are segmented by punctuation, and text data exceeding 10 Chinese characters are selected. The data are then randomly divided into training and test sets in a 6:1 ratio, forming DATE2. The third step involves analyzing the collected data. First, the optimal number of topics is calculated based on perplexity scores, and topic clustering is performed on DATE1 using the LDA model. This forms the evaluation indexes for the tourism elements of the historic district, derived from the overall characteristics of each topic. The weight of each index is calculated based on keyword frequency within these topics. Next, sentiment analysis is conducted on DATE2 using the BERT model, yielding a probability distribution of positive, neutral, and negative sentiments for each topic. In the fourth step, the evaluation results are normalized across two dimensions: the weights of the evaluation indicators and the probability of positive sentiment distribution. Using the weights to represent importance and the positive sentiment distribution to represent satisfaction, IPA analysis is applied to visually illustrate the performance-satisfaction outcomes for each indicator (Fig. 2).

Data sources and processing

Data sources

This study utilizes reviews of Taiping Old Street from VW Dianping (https://www.dianping.com) as the primary data source. VW Dianping, China’s leading platform for local lifestyle information and transactions, is also recognized as the world’s first independent third-party consumer review website. As a professional review platform, it boasts a large user base and provides comprehensive evaluation data. Using Python, the comment texts related to Taiping Old Street were scraped from VW Dianping’s review section. The collected data includes the reviewer’s name, review date, rating score, and review content, resulting in a total of 8872 initial reviews.

Data processing

-

(1)

Evaluation indicators and weights section

This study involves crawling review texts related to Taiping Old Street from popular review platforms using Python. The initial review texts are often written in non-standard language and contain a significant amount of noise; thus, data processing is necessary to enhance the usability of these texts for machine learning. The data processing consists of six steps. First, preliminary data processing. The comment information is organized and analyzed by removing irrelevant data such as duplicate comments, advertisements, and unrelated entries, resulting in a total of 8800 valid comments. Second, remove unnecessary words. The Jieba library in Python is used to preprocess the raw data by removing filler words and meaningless terms. Using the Chinese stop-word list, irrelevant words, quantifiers, adverbs, and symbols that could affect thematic analysis—such as “haha,” “wow,” “one,” “all the time,” etc.—are deleted. The data is then further processed using the Jieba library. Third, a custom thesaurus is created. Local characteristic words from Taiping Old Street, such as “Cha Yan Yue Se,” “Sugar and oil” and “Jia Yi’s former residence” are added to the thesaurus. This enhances the accuracy of word classification and strengthens the relevance between the vocabulary and the research object. Fourth, replace near-synonyms. Construct a thesaurus of near-synonyms, treating all synonyms as equivalent terms. For example, “Taiping Street,” “Taiping Old Street” and “Old Street” can be uniformly replaced with “Taiping Old Street,” while “shop” and “small shop” can be consolidated into “shop.” Fifth, Python’s Jieba library is used to segment the processed data and extract keywords from the comment text. Sixth, frequency statistics are conducted on the segmented data to identify high-frequency topic words and generate a vocabulary frequency table. Following these steps, a total of 173,811 valid data samples were obtained, referred to as DATE1.

-

(2)

Emotional analysis

In Chinese writing, a complete sentence often contains multiple elements. For instance, “The food here is quite good, but there are too many people, you have to queue up everywhere you go, and there is no resting place.” This single comment addresses the food, environment, and infrastructure, where the sentiment about food is positive, but the sentiment about the environment and infrastructure is negative. Therefore, in sentiment analysis of review texts, it is essential to divide each review into multiple phrases. The data processing consists of three steps: first, utterance segmentation. In Chinese texts, punctuation is commonly used to segment utterances. Thus, this study adopts punctuation marks such as “”, “?”, “!”, and “..” as the basis for text segmentation to ensure maximum correspondence between the topic and the evaluation content. This method resulted in a total of 84,082 data points after text segmentation. Second, screening and analysis. Longer statements are more conducive to semantic analysis in connection with the context, so data containing more than 10 Chinese characters are selected as samples for sentiment analysis, resulting in a total of 27,013 entries. Third, deletion of useless data. Blank, repetitive, and non-sentimentally inclined comments were removed. After these steps, 25,638 valid samples containing thematic evaluation content were obtained, named DATE2.

Research methodology

Evaluation of the construction of indicators

In this study, evaluation metrics are constructed based on the topics and high-frequency keywords extracted from the LDA topic model, one of the most powerful techniques in text mining for data analysis, latent pattern discovery, and identifying relationships between data and text documents25. The LDA topic model is highly effective in analyzing the complex structures of documents, topics, and words in review texts, revealing hidden topic patterns and relationships. By using LDA, meaningful evaluation indices can be extracted from large volumes of unstructured text data, enhancing the scientific rigor of index selection and reducing the bias inherent in manual classification. The LDA model uncovers the probability distribution of topics in review texts, such as those in the VW Review dataset, by analyzing the three-tier structure of documents, topics, and words. As shown in Eq. (1), this analysis process generates a matrix vector consisting of n topics and corresponding m keywords. Each column represents the probability distribution of each word across the m topics, while each row represents the probability distribution of each topic across the n words.

This article adopts Perplexity, a scientific model used to determine the optimal number of topics K. Perplexity is a key metric in natural language processing that measures the predictive power of language models. It has a solid theoretical foundation and is widely applied in the evaluation of topic models. The formula for calculating topic perplexity is presented in Eq. (2):

In this equation, p(w) represents the probability of each word in the test set, and N denotes the number of words or the total length of the test set. The rationale behind this is that when the model has a higher probability of predicting words in the test set, the perplexity value decreases, indicating that the model performs better on that test set. In other words, a lower perplexity suggests that the model’s thematic structure is relatively stable and the expected error is smaller. A lower perplexity also means the model can capture the semantic information in the text more accurately, thus fitting the data better. The effectiveness and importance of perplexity in topic model evaluation have been discussed in numerous studies. For example, Hoffman et al. used perplexity to evaluate the performance of LDA models on different datasets and demonstrated that perplexity effectively reflects the degree to which the model fits the data, providing an important basis for model parameter selection and optimization47. Wallach et al. elaborated on the advantages of perplexity as an evaluation metric for topic models, emphasizing its key role in measuring the relationship between the model and the data, which provided strong theoretical support and practical reference for its use in this study48.

In this study, we calculate the perplexity for different numbers of topics using the scikit-learn package in Python. The specific results show that the perplexity is lowest when the number of topics is 7, indicating that this is the optimal equilibrium point, where the model achieves its best predictive performance.

The process of constructing the evaluation index is as follows: First, high-frequency keywords are screened. DATE1 is used as the data sample, and the trained LDA topic model classifies DATE1 into 7 topics, generating a “topic-vocabulary” matrix. The selection of high-frequency topic words is based primarily on word frequency statistics, supplemented by the TF-IDF index49. The top 10 most frequent words in each topic are selected as high-frequency candidates, which are then verified using the TF-IDF index. To ensure low-frequency keywords are not overlooked, a review panel was established, consisting of experts in the fields of culture and tourism, senior merchants from Old Street, and frequent travelers. This panel manually screens low-frequency words associated with the model-generated topics to identify potential high-impact indicators50. Additionally, this process was used to fine-tune the parameters of the LDA model, moderately increasing the weight of low-frequency keywords in subsequent iterations. This adjustment helps the model adapt more effectively to complex tourism scenarios, taking into account both high-frequency general terms and low-frequency specific features.

Next, the evaluation team—comprising culture and tourism experts, senior merchants, and frequent travelers—generated evaluation indicators by summarizing the characteristics of the high-frequency keywords in each topic. For example, topic 1, which is closely related to local snacks, business, food, shopping, drinks, entertainment, and other factors, highlights the basic needs of tourists and is therefore categorized as “Regional Function.” Similarly, the topics of topics 2 through 7 were described as follows: Spatial Accessibility, History and Culture, Environmental Features, Local Characteristics, Management Services, and Tourism Experience.

Evaluation indicator weights

In this study, the weights of the topics are determined based on the frequency of the corresponding keywords within the “topic-vocabulary” matrix. The high-frequency keywords are then summarized to derive feature words that represent the content of each topic. The weight of each topic is calculated using Eq. (3).

In this formula, Ik represents the weight of the topic, nk,j is the number of occurrences of the keyword associated with the topic in document dj, and the denominator is the total occurrences of all keywords in document dj. The weights of each topic were calculated using Eq. (3) based on the results of the seven topics identified by the LDA model.

Sentiment analysis

In this study, the BERT model is employed to conduct sentiment analysis, offering deeper contextual sentiment capture compared to traditional natural language processing (NLP) techniques such as Word2Vec, CNN, RNN, and Bi-LSTM51. The BERT model consists of an input layer, a Transformer encoder layer, and an output layer. First, comment text from DATE2 is processed, with each piece of data transformed into a sequence of word embeddings, starting with [CLS] tags and ending with [SEP] tags. This sequence is then passed through BERT’s Transformer encoder to extract deep contextual semantic information. Specifically, the model takes as input the embedding containing the [CLS] token (X0) and the text sequence embeddings (X1 to XN). These inputs are then encoded through BERT’s multi-layer Transformer structure to generate high-level feature representations. Finally, the output layer uses a softmax function to transform the encoded representations into probability values for each classification result, indicating the likelihood of each sentiment category (Fig. 3).

After this process, the model can accurately identify the emotional tendencies of the comment text and classify the text into three categories: positive, negative, and neutral emotions. Finally, subject satisfaction is calculated based on the classification results, with the calculation formula presented in Eq. (4).

Where P represents the number of positive comments, N is the number of neutral comments, Neg is the number of negative comments, and T is the total number of comments for a given topic. The weights for each sentiment are defined as: Wp = 1 for positive comments, Wn = 0 for neutral comments, and Wneg = −1 for negative comments. DATE2 is used as the data sample for sentiment analysis, with the data classified according to the keywords of the topics in each piece of data before the analysis. Using the LDA model, the keywords of each topic are identified and matched with the corresponding comments from DATE1. This keyword matching determines the relevant topic for each comment. For example, in DATE2, if a comment states, “The sugar and oil here is super delicious,” the keyword “sugar and oil” can be located in DATE1. Based on this match, the comment is classified into the corresponding topic.

The IPA method of analysis

Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) is used to gain detailed insights into the performance of tourism elements on Taiping Old Street. IPA was first introduced by Martilla and James in 199752. Its fundamental concept is to assess the importance of various factors influencing user satisfaction and to evaluate the actual performance of these factors as experienced by users. The goal is to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the evaluated elements. The IPA four-quadrant diagram provides a clear visualization of both the development priorities for tourism factors in Taiping Old Street and the level of user satisfaction with these factors, based on users’ evaluations. In this analysis, the weight of each topic is considered as “Importance,” as shown in Eq. (5), while the distribution of topic satisfaction is represented as “Performance,” as in Eq. (6). “Importance” is used as the horizontal coordinate, and “Performance” is used as the vertical coordinate. The methods for calculating “Ik” (Importance) and “Pk” (Performance) were introduced in Eqs. (3) and (4) in the previous section. To establish the four-quadrant graph, the average values of “Importance” and “Performance” serve as the dividing lines for the horizontal and vertical axes, respectively. Based on these axes, the IPA diagram divides the evaluation indicators into four quadrants: Advantage, Opportunity, Vulnerable, and Patch. This allows for a visual representation of the performance satisfaction of each tourism element.

Model performance evaluation

To evaluate the validity and reliability of the constructed model, we employed a cross-validation approach. The dataset was divided into seven equal subsets. In each iteration, one subset was selected as the validation set, and the remaining six subsets were used for training. The model was trained on the training data, and evaluation metrics were computed based on the validation set. This procedure was repeated such that each subset was used as the validation set once. The final performance metric was determined by averaging the evaluation results from all iterations. In this study, we primarily used four evaluation metrics: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and the F1 score. Accuracy is defined as the proportion of correctly predicted instances out of the total number of samples. Precision refers to the proportion of true positive predictions among all predicted positive samples. Recall represents the proportion of true positives among all actual positive instances, and the F1 score is the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall53, which is calculated using the following formula:

In this study, the following terms are used to define the model’s performance: TP (True Positive) represents the number of samples that are actually positive and predicted as positive by the model; TN (True Negative) refers to the number of samples that are actually negative and predicted as negative by the model; FP (False Positive) denotes the number of samples that are actually negative but predicted as positive by the model; and FN (False Negative) represents the number of samples that are actually positive but predicted as negative by the model. The results of the cross-validation for both the LDA and BERT models are presented in Table 1.

The results show that the LDA model achieves high accuracy and F1 score in topic classification, indicating its effectiveness in clustering review texts and accurately identifying the topics of different tourism elements. The BERT model also performs well in sentiment analysis, with high accuracy, recall, and F1 scores, demonstrating its ability to accurately assess the sentiment of the texts and provide a better understanding of tourists’ evaluations for precise classification.

Results

Evaluation indicators and weights

The results from the Table 2 experiment show that users’ evaluation topics of Taiping Old Street are diverse and varied. These topics not only encompass material and spatial aspects, such as physical function, spatial accessibility, environmental features, and local characteristics, but also include subjective topics like history and culture, management services, and tourism experiences.

As shown in Table 2, RF has the largest number of keywords and the highest weight of 0.412. This topic primarily focuses on the regional functions of historic blocks, with keywords related to commerce, food and drink, and shopping, indicating that these functions hold a dominant position in the text. The EC follows, with a weight of 0.269, encompassing the city’s environmental features, particularly elements such as streets, architecture, and historical and cultural aspects. The SA, HC, LC, and TE have relatively moderate weights. The SA emphasizes the importance of spatial accessibility, with keywords focused on transportation and location, especially concerning the metro and walking. The HC keywords highlight historical buildings and cultural sites, while LC keywords concentrate on local cuisine and culture. The TE reflects the tourist experience, particularly aspects like nightlife, travel experiences, and the business atmosphere, which mainly represent tourists’ subjective feelings toward Taiping Old Street. The MS has the smallest weight of 0.009, primarily related to management and service, with keywords focusing on price, service quality, and facilities.

The analyses based on the keywords corresponding to each topic reveal an uneven distribution of different topics in the comment texts. The results indicate that keywords under the RF, HC, EC, and LC topics, such as “Snacks” (RF1), “Taiping Old Street” (HC1, EC1), and “Stinky Tofu” (LC1), are the primary focus of discussion, with word frequencies of 8879, 9255, and 5649, respectively, and percentages of 0.511, 0.0532, and 0.0325. In contrast, other keywords received relatively little attention. The keywords in each topic exhibit a typical long-tail distribution, with the word frequency and percentage of each topic demonstrating the characteristic of “a few core elements dominating” (Fig. 4).

Relationship between evaluation indicators

When analyzing the keywords of each topic, significant cross-correlations were identified, reflecting the interdependence and integration of urban functions and characteristics (Fig. 5). The RF and LC both include keywords related to commerce and food, such as “stinky tofu” “Cha Yan Yue Se” and “Wen He You” Similarly, the HC and EC topics encompass keywords for historical sites and cultural places, including “Taiping Old Street” “Jia Yi’s Residence” and “Wen He You” This crossover indicates that history and culture are not confined to specific cultural topics but are deeply embedded in the city’s environmental characteristics, influencing its overall appearance. The SA and EC also intersect in geographic location and spatial layout, exemplified by landmarks like “Wuyi Square.” Although MS and TE contain fewer overlapping keywords, those related to management and services, such as “price,” “service quality” and “facilities” are indirectly reflected in the TE.

Sentiment analysis of tourism elements

Sentiment analysis of topic

The sentiment analyses derived from the test set revealed the following results: positive comments totaled 3052, negative comments amounted to 273, and neutral comments reached 948. The final calculations are summarized in Table 3. The remaining training set was utilized to validate the sentiment distribution of the test set, confirming its reasonableness.

The results show that “TE” and “HC” received the highest positive ratings, with 82.28% and 77.44% of positive feedback, respectively, reflecting a high level of recognition from tourists. In terms of neutral evaluations, “SA” and “LC” received relatively high proportions of neutral feedback, with 29.84% and 24.17%, respectively, while “RF” also had 24.01% of neutral evaluations. Regarding negative feedback, “MS” and “RF” received the most negative ratings, with 14.29% and 7.40%, respectively. Overall, the sentiment analysis indicates that the “TE” and “HC” elements of Taiping Old Street are the most praised by tourists, while the “SA” element performs poorly and requires further optimization.

Sentiment analysis of keyword

The sentiment analysis graph of high-frequency keywords for each topic in the evaluation text of Taiping Old Street reveals significant differences in sentiment distribution across tourists’ comments (Fig. 6). First, in the RF and LC topics, keywords related to food, such as “Snacks” and “Stinky Tofu” received highly positive evaluations, far exceeding neutral and negative assessments. However, for the keyword “Business” despite having 19 positive ratings, there were also 11 neutral and 8 negative ratings. In the SA, keywords like “Pedestrian Flow” and “Walk” which pertain to infrastructure, exhibited a higher percentage of neutral and negative comments. In the HC and EC topics, keywords related to culture and history, such as “Taiping Old Street,” “History,” and “Culture” garnered the majority of positive feedback. The analysis of the MS topic indicated that negative and neutral sentiments were more pronounced in comments concerning “Price” with keywords like “Garbage” and “Service” also reflecting a certain proportion of negative sentiment. In the TE topic, keywords such as “Night,” “Lively,” and “Delicious” which describe the overall atmosphere and experience, received nearly all positive comments, while keywords like “Queue” and “Crowded” revealed a dichotomy in attitudes.

Meanwhile, based on the co-occurrence frequency of keywords from different topics in the same comment text, it was found that RF and LC, as well as EC and HC, demonstrated strong correlations in positive, neutral, and negative comments (Fig. 7). This reflects the close interconnection of these elements in visitors’ feedback.

IPA analysis

Based on the results of the IPA analysis, this study offers a detailed classification and summary of the tourism elements of Taiping Old Street (Fig. 8). The findings indicate significant variation in the performance of these elements concerning tourist satisfaction and importance, allowing them to be categorized into four distinct quadrants.

The tourism element that falls into the first quadrant is EC, indicating that tourists’ attention and satisfaction with this element are high. This suggests that EC is a core strength in the tourism experience of Taiping Old Street, which should be maintained and strengthened. The environment of Taiping Old Street provides a positive experience for tourists. The tourism elements that fall into the second quadrant are TE and HC, which are relatively less important, although they perform well in terms of satisfaction. This means that, while these elements bring high levels of satisfaction, they are not widely recognized or valued by tourists in the current tourism experience. The elements in the third quadrant are LC, MS, and SA, which have some shortcomings in terms of satisfaction, even though they are of relatively low importance to tourists. Located in the fourth quadrant is RF, which represents a disadvantage in the overall tourism element evaluation system. This element has the high importance, yet satisfaction is at a low level. This finding suggests that the lack of regional functionality may be a major factor affecting the overall tourism experience in Taiping Old Street.

Discussion

Theoretical contributions to the evaluation of tourism elements

The theoretical contributions of this study are reflected in four key aspects: the research object, data sources, evaluation indexes, and the accuracy of the evaluation results. (1) With regard to the research object, while the evaluation of tourism elements in general has become relatively mature, there remains a significant gap in evaluating tourism elements specific to historic districts. Unlike other scenic spots, historic districts place particular emphasis on historical and cultural elements, which are a key focus for tourists. Therefore, this study employs machine learning techniques to evaluate tourism elements in historic districts, aiming to address this gap. (2) Regarding evaluation data sources, soft data—primarily obtained through questionnaires or interviews—still dominate. These data are often derived from small sample sizes based on surveys or observations, resulting in findings that are only representative of specific times and regions. Although hard data offers a more objective and comprehensive approach to evaluating the research object, its use in tourism element evaluation remains limited. This study aims to address this limitation by utilizing text data from reviews on popular review websites, providing a more comprehensive evaluation of tourism elements in historic districts. (3) In terms of the methodology for evaluating indicators, most existing studies rely on the Delphi method or incorporate qualitative research techniques, such as grounded theory, to conduct detailed systematic categorization. While these methods are scientifically valid, they face challenges due to the large volume of unstructured data, which complicates semantic analysis and the widespread adoption of methodologies. To overcome this limitation, this study employs the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) model, a machine learning technique, to classify topics in social media comments, thereby informing the determination of evaluation indicators. This approach enhances the scientific rigor of indicator selection and mitigates the biases inherent in manual categorization. (4) Previous evaluation results often lack an objective basis. Both qualitative and quantitative methods in earlier studies still rely heavily on scoring by tourists or experts. These scoring systems, typically on a 1-5 scale, are often vague, with terms such as “excellent,” “good,” “average,” “bad,” and “very bad,” which fail to provide precise data support. To address this, the current study categorizes sentiment in review texts using the BERT model, which analyzes sentiment tendencies across various topics in detail. Compared to traditional methods, the bidirectional structure of the BERT model enables more accurate sentiment analysis, offering a stronger representation of evaluation results.

This study introduces two key innovations compared to previous studies on the application of machine learning to tourism element evaluation: (1) Combination of LDA and BERT Models: This study integrates the LDA model with the powerful semantic feature extraction capabilities of BERT to analyze review texts for sentiment tendencies. The framework not only identifies important keywords but also considers the overall semantics and context of the reviews, improving the accuracy and comprehensiveness of sentiment recognition. (2) Exploring Correlations Between topics and Keywords: Unlike earlier studies that focused solely on the importance and satisfaction of individual keywords, this study explores the correlations between topics and keywords. This analysis compensates for the limitations of previous studies by providing a deeper understanding of tourists’ attention and emotional tendencies toward tourism elements. It also uncovers the underlying drivers behind these evaluations. In theory, this study proposes a new evaluation method based on machine learning, while in practice, it offers more comprehensive strategic suggestions for the innovative enhancement of tourism elements.

Practical implications for enhancing the visitor experience

This study provides a comprehensive evaluation of the tourism elements of Taiping Old Street and offers practical suggestions for enhancing the tourist experience. Based on the evaluation results, the following strategies are proposed:

In the RF topic, According to the IPA analysis, the RF topic, although frequently mentioned in the overall review text, has a low satisfaction level. This finding suggests that the lack of regional functionality may be a key factor negatively impacting the overall tourism experience at Taiping Old Street. While RF-related mentions are common and sentiment toward it is generally positive, this indicates that local businesses and catering services are major attractions for tourists. However, the catering function currently dominates over the other tourism functions by a large margin. Therefore, to enhance the functional experience, the first step should be to reduce the redundancy of catering services and promote a more balanced development of the six tourism elements: food, accommodation, transportation, tourism, shopping, and entertainment. It is also essential to eliminate online shops that are not aligned with the local culture and clearly define the industry’s entry and exit mechanisms. Furthermore, the tourism experience can be enriched by developing a regional food brand54, which would improve tourist satisfaction by connecting local food offerings with regional characteristics.

In the SA topic, improving transportation and accessibility is crucial to enhancing the tourism experience, particularly given the low satisfaction levels in this area. The findings indicate that “pedestrian flow” and “walking” are the primary sources of negative feedback. Therefore, clearer directional signs and rest areas should be installed at popular attractions and public transport hubs to alleviate the negative experiences caused by congestion. Additionally, collaborating with transport providers to increase the frequency and accessibility of public transport services during peak tourist seasons will help reduce congestion and improve overall accessibility. Furthermore, the rational layout of tourism-related businesses should prioritize areas with high traffic accessibility and concentrations of tourism elements, especially food, beverage, and shopping businesses, which tend to have higher customer flow and should therefore be located in these areas.

In the HC topic, tourists show less interest in the historical and cultural aspects, reflecting the over-commercialization phenomenon in the neighborhood, which threatens the integrity and originality of local history and culture. Authenticity, which refers to how tourists perceive and appreciate the historical and cultural resources of a destination, plays a crucial role in shaping their experience55. Research has shown that authenticity is tied to both tourists’ understanding of intangible heritage and the quality of tangible heritage, which significantly influences their overall experience56. Therefore, enhancing the impact of history and culture should involve a comprehensive approach that combines both tangible and intangible heritage. A multifaceted display of history and culture is essential to strengthen tourists’ perception and identification with these elements. First, a diversified presentation of historical and cultural elements should be prioritized. Utilizing innovative AR visualization techniques57 and experience design can offer a more immersive and interactive exploration of the history, culture, and architectural details of historic districts. For example, digital tours of architecturally significant heritage sites, such as Jia Yi’s former residence, can be facilitated through heritage digitization technology58, while historical storytelling59 and intangible cultural heritage experiences60 can further enrich the cultural experience and deepen visitors’ engagement. Second, for architectural sites with lower historical significance, such as the Taiping Granary, which are less frequently perceived by tourists, a more community-oriented approach can be adopted. These sites can be repurposed for public use and connected to local functions. Organizing traditional cultural ceremonies and festivals61 within the neighborhood can help restore the connection between the site and its indigenous heritage.

In the EC topic, tourists are particularly concerned with environmental factors such as buildings and streets. Therefore, local authorities should prioritize the preservation of local architectural heritage, ensuring that these structures become key attractions for tourism in historic districts. Additionally, the cleanliness and greenery of the streets should be enhanced by increasing the frequency of street cleaning, implementing stricter waste management policies, and planting more trees and flowers to improve the area’s aesthetics. Furthermore, efforts should be made to control noise levels, particularly in areas with high tourist traffic, to create a more pleasant and welcoming environment for visitors.

In the LC topic, the high-frequency keywords are strongly associated with food. Therefore, the tourism experience can be enhanced by establishing a regional food brand54, which can increase visitor satisfaction by linking food with local characteristics. Additionally, local merchants and artisans should be supported in promoting and selling traditional handicrafts, as well as developing other products that highlight local features, beyond just specialty foods. Finally, cultural heritage protection regulations should be enforced to prevent the loss of local identity due to over-commercialization.

In the MS topic, “Price” generates a significant amount of negative sentiment, reflecting the tourism board’s insufficient control over pricing. Local tourism authorities should regularly monitor and assess commodity prices to ensure they remain within reasonable market levels. Additionally, training programs should be implemented for tourism staff to improve their service skills and customer service awareness, including courses on effective communication, problem-solving, and handling customer complaints. Furthermore, a feedback mechanism should be established to allow tourists to easily report issues and provide suggestions for improvement.

In the TE topic, keywords such as “many people” and “quaint” appeared. These negative descriptions of the site’s atmosphere significantly impacted tourists’ travel experiences. Meanwhile, keywords like “night” and “delicious” under the TE topic suggest that night tourism and culinary experiences are key factors in enhancing tourist satisfaction. Atmosphere provides the foundation for an immersive tourism experience and is an essential factor in improving the overall experience62. In tourism, ambience is understood as a by-product that emerges from the space and events, and it is shaped by all tourism elements working together. Atmosphere originates from both human and non-human activities in the area, each with a unique rhythm, providing tourists with distinct visual, auditory, and olfactory sensations63. Therefore, to enhance the tourist experience, designers can focus on developing specialty tourism to elevate the area’s atmosphere. First, a variety of night-time cultural tourism venues, such as special snack night markets and 24-hour bookstores, should be developed in the historic district, closely integrating them with local characteristics and culture to create a unique brand for night tourism64. Second, organizing tourism-related ceremonial activities that combine history and culture can stimulate tourists’ sense of awe, sanctity, and identity65. Finally, improving supporting facilities that enhance the atmosphere—such as architecture, decoration, color, lighting, sound, and music—can further enrich the experience. For example, playing appropriate music or setting off fireworks in certain areas can amplify the atmosphere of the tourism environment.

Limitations and future research

The evaluation system proposed in this study has some limitations that should be addressed in future research.

(1) Regarding the data source, while user-generated review data offers an irreplaceable advantage, it primarily reflects a large number of visitor evaluations, covering various tourism elements such as dining, accommodation, shopping, and sightseeing experiences during tourists’ visits to Taiping Old Street. This data provides a valuable window into tourists’ immediate, subjective experiences. However, due to the specificity of the study area and the age distribution concentration of the evaluation population, it is challenging to develop a comprehensive set of indicators that can represent all potential tourism elements of the historic district. The active users on review platforms tend to be younger consumers, enthusiastic about sharing their travel experiences, and this group typically has specific preferences and aesthetic views. As a result, it is difficult to fully represent tourists of different ages, regions, and travel purposes. For instance, elderly tourists may prioritize leisure facilities and barrier-free access, while family tourists are more concerned with child-friendly rides and safety features. These aspects may not be adequately captured in the available review data. Additionally, the objectivity of Dianping data can be influenced by factors such as merchants’ promotional activities, where some businesses may encourage customers to provide high ratings, or individual users may post extreme negative comments due to unresolved disputes, distorting the authenticity of the reviews. This mix of commercial marketing and personal emotions can compromise the data’s reliability, weakening its ability to accurately represent the overall tourism ecosystem. Future research could expand the data sources and study area by incorporating social media, field surveys, and other data systems, allowing for a more comprehensive analysis of tourism elements in historic districts across multiple aspects, levels, and time periods. This expansion could include a combination of user-generated content (UGC)39, social media big data40, POI data66, geospatial big data67, field trip data68, and survey data69 to form a multi-source database for analyzing and evaluating tourism elements from diverse perspectives. Data from different sources are cross-validated to ensure consistency and reliability. For specific tourism elements in historical and cultural neighborhoods, such as the use of barrier-free facilities and the demand for children’s play areas, targeted questionnaires or field observation programs can be designed to ensure these elements are adequately included in the evaluation system. (2) The analysis in this study focused solely on textual data, neglecting the valuable insights that emoticons and images embedded in the review text can provide. Future research could enhance the tourism element evaluation system by further developing and applying deep learning models to detect tourism elements and evaluate sentiment from emoticons70,71 and photos72. (3) As an evaluation system study, this study primarily examined the relationship between tourism elements and sentiment classification. Future studies could include additional variables such as time, location73, gender74, and income level75 to enrich the factors considered in evaluating tourism elements. (4) The tourism elements in this study were primarily evaluated around Taiping Old Street in Changsha City, which limits the direct generalizability of the findings and the framework to some extent. In future research, we plan to expand the study area to include a broader range of historical and cultural neighborhoods for comparative analysis, aiming to further validate and refine the framework to enhance its applicability across different scenarios. Additionally, we will actively explore how the framework can be adjusted and optimized according to the characteristics of different neighborhoods, ensuring its adaptability to diverse historical and cultural environments.

Conclusion

This study proposes a comprehensive evaluation system for tourism elements in historic districts using machine learning methods, providing a scientific basis for the subsequent optimization of these elements. The analysis focuses on Taiping Old Street as a case study, utilizing data from Dianping.com, a leading local life information platform in China. For indicator selection and weight calculation, the tourism elements identified in the evaluation texts are categorized using LDA topics. This process yields seven evaluation indicators: RF, SA, HC, EC, LC, MS, and TE. The weights of these indicators are calculated based on the frequency of keyword appearances. In terms of sentiment analysis, the BERT model enables precise categorization of sentiments related to the evaluation indicators of tourism elements in historic districts, ultimately presenting their importance and satisfaction visually in an IPA four-quadrant diagram. This method addresses the shortcomings of previous manual data collection techniques, facilitating a more accurate selection of evaluation indicators and improving the reliability of weight assignment and scoring. The findings reveal that EC garners much attention from tourists and achieves higher satisfaction compared to other elements. TE and HC also perform well in terms of satisfaction, although their importance is relatively lower. Conversely, LC, SA and MS rank low in both importance and satisfaction. Notably, RF has low satisfaction despite its high importance. Therefore, prioritizing improvements in RF is essential for better meeting tourist needs and enhancing the overall tourism experience at Taiping Old Street. These results can guide urban planners and tourism managers in targeting future development efforts to enhance visitor satisfaction, with a focus on optimizing elements in vulnerable and disadvantaged areas to improve the overall experience in the historic district.

Data availability

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Abbreviations

- RF:

-

Regional function

- SA:

-

Space accessibility

- HC:

-

Historic culture

- EC:

-

Environmental characteristics

- LC:

-

Local characteristics

- MS:

-

Management and service

- TE:

-

Tourism experience

References

Corbusier, L. & Eardley, A. The Athens Charter (Grossman, 1973).

Amir, S., Osman, M. M., Bachok, S. & Ibrahim, M. Sustaining local community economy through tourism: Melaka UNESCO World Heritage City. Procedia Environ. Sci. 28, 443–452 (2015).

Xiao-gen, W. & Ying-ying, D. Empirical study on perceptive image formation of tourists on tourism destination: a case study of Nantong Jiangsu Province. Geogr. Res. 30, 1554–1565 (2011).

Naoi, T., Airey, D., Iijima, S. & Niininen, O. Towards a theory of visitors’ evaluation of historical districts as tourism destinations: frameworks and methods. J. Bus. Res. 60, 396–400 (2007).

Zhang, S., Zhang, Z., Yu, H. & Zhang, T. Assessment and empirical research on the suitability of eco-tourism development in nature reserves of China: a multi-type comparative perspective. Land 13, 438 (2024).

Nedeljković, M., Puška, A., Štilić, A. & Maksimović, A. Examining of the sustainable rural tourist potential of Semberija using multi-criteria analysis methods. Environ. Dev. Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-04395-3 (2024).

Milman, A. & Tasci, A. D. A. Exploring the experiential and sociodemographic drivers of satisfaction and loyalty in the theme park context. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 8, 385–395 (2018).

Peng, Y., Liu, W., Xiong, C. & Bai, X. Value transformation and ecological practice: the path to realizing the value of ecotourism products in heritage sites—a case study of the Qitai Dry Farming System in Xinjiang. Sustainability 16, 5031 (2024).

YaQing, G. Evaluation of agricultural cultural heritage tourism resources based on grounded theory on example of ancient Torreya grandis in Kuaiji mountain. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 19, 1193–1199 (2018).

Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Seyfi, S., Rather, R. A. & Hall, C. M. Investigating the mediating role of visitor satisfaction in the relationship between memorable tourism experiences and behavioral intentions in heritage tourism context. Tour. Rev. 77, 687–709 (2022).

Zhang, S. et al. Construction of cultural heritage evaluation system and personalized cultural tourism path decision model: an international historical and cultural city. J. Urban Manag. 12, 96–111 (2023).

Yongle, L., Fei, C. & Guihong, H. On the tourist experience based on web text of historical and cultural district of the Grand Canal. Nanjing J. Soc. Sci. https://doi.org/10.15937/j.cnki.issn1001-8263.2021.02.019 (2021).

Li, F. & Dong, F. Y. Grey clustering evaluation on regional tourism economy development in China. In Proc. 2013 IEEE International Conference on Grey Systems and Intelligent Services (GSIS), 274–279 (2013).

Zhang, H., Gu, C. L., Gu, L. W. & Zhang, Y. The evaluation of tourism destination competitiveness by TOPSIS & information entropy—a case in the Yangtze River Delta of China. Tour. Manag. 32, 443–451 (2011).

Chen, Y. Y. et al. Evaluation of tourism development potential on provinces along the Belt and Road in China: generation of a comprehensive index system. Land 10, 905 (2021).

Yi, K., Mao, X. L., Cheng, H. L., Zhang, L. G. & Zhang, D. A. Evaluation of information service in smart scenic area based on “SEM-ANP” synthetic evaluation mode. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 41, 2765–2777 (2021).

An, L. T., Markowski, J., Bartos, M., Rzenca, A. & Namiecinski, P. An evaluation of destination attractiveness for nature-based tourism: recommendations for the management of national parks in Vietnam. Nat. Conserv. 32, 51–80 (2019).

Wu, Y. C. & Lin, S. W. Efficiency evaluation of Asia’s cultural tourism using a dynamic DEA approach. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 84, 101426 (2022).

Jiang, P., Shao, L. & Baas, C. Interpretation of value advantage and sustainable tourism development for railway heritage in China based on the analytic hierarchy process. Sustainability 11, 6492 (2019).

Ma, H., Li, S. & Chan, C.-S. Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)-based assessment of the value of non-World Heritage Tulou: a case study of Pinghe County, Fujian Province. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 26, 67–77 (2018).

Chen, C.-A. Suitable festival activities for Taiwan’s tourism and nation branding with the application of the PR AHP program. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 19, 1381–1398 (2014).

Sasongko, I., Gai, A. M. & Azzizi, V. T. Sustainable development concept of heritage Kampung tourism using novel prioritization approach. Sustainability 16, 2934 (2024).

Boley, B. B., McGehee, N. G. & Hammett, A. L. T. Importance-performance analysis (IPA) of sustainable tourism initiatives: the resident perspective. Tour. Manag. 58, 66–77 (2017).

Tripathy, A., Agrawal, A. & Rath, S. K. Classification of sentiment reviews using n-gram machine learning approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 57, 117–126 (2016).

Jelodar, H. et al. Latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) and topic modeling: models, applications, a survey. Multimed. Tools Appl. 78, 15169–15211 (2019).

Gao, Z. J., Feng, A., Song, X. Y. & Wu, X. Target-dependent sentiment classification with BERT. IEEE Access 7, 154290–154299 (2019).

Sun, Q. Preservation and renewal of historical and cultural blocks under urban RBD model: a case study of Baoding West Street. E3S Web Conf. 553, 04006 (2024).

Naoi, T., Yamada, T., Iijima, S. & Kumazawa, T. Applying the caption evaluation method to studies of visitors’ evaluation of historical districts. Tour. Manag. 32, 1061–1074 (2011).

Giannakopoulou, S., Xypolitakou, E., Damigos, D. & Kaliampakos, D. How visitors value traditional built environment? Evidence from a contingent valuation survey. J. Cult. Herit. 24, 157–164 (2017).

Li, Y. Research on the protection and restoration of historical blocks based on landscape cultural ecology. In Proc. 2016 International Conference on Contemporary Education, Social Sciences and Humanities, 362–365 (2015).

Battilani, P., Bernini, C. & Mariotti, A. How to cope with dissonant heritage: a way towards sustainable tourism development. J. Sustain. Tour. 26, 1417–1436 (2018).

Cranmer, E. E., tom Dieck, M. C. & Jung, T. The role of augmented reality for sustainable development: evidence from cultural heritage tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 49, 101196 (2023).

Zhao, X., Elahi, E., Wang, F., Xing, H. & Khalid, Z. Sustainable tourism development for traditional Chinese drama’s intangible cultural heritage. Heliyon 10, e25483 (2024).

Hosseini, K., Stefaniec, A. & Hosseini, S. P. World Heritage Sites in developing countries: assessing impacts and handling complexities toward sustainable tourism. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 20, 100616 (2021).

Weng, L. S., He, B. J., Liu, L. N., Li, C. X. & Zhang, X. Sustainability assessment of cultural heritage tourism: case study of Pingyao Ancient City in China. Sustainability 11, 16 (2019).

Al-hagla, K. S. Sustainable urban development in historical areas using the tourist trail approach: a case study of the Cultural Heritage and Urban Development (CHUD) project in Saida, Lebanon. Cities 27, 234–248 (2010).

Cetin, M. Evaluation of the sustainable tourism potential of a protected area for landscape planning: a case study of the ancient city of Pompeipolis in Kastamonu. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 22, 490–495 (2015).

Santos, F., Almeida, A., Martins, C., Gonçalves, R. & Martins, J. Using POI functionality and accessibility levels for delivering personalized tourism recommendations. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 77, 101173 (2019).

Lee, J.-S. & Park, S. A cross-cultural anatomy of destination image: an application of mixed-methods of UGC and survey. Tour. Manag. 98, 104746 (2023).

Li, H., Li, M., Zou, H., Zhang, Y. & Cao, J. Urban sensory map: how do tourists “sense” a destination spatially? Tour. Manag. 97, 104723 (2023).

Li, C., Gao, L., Liu, Y. & Li, H. Cluster analysis of China’s inbound tourism market: a new multi-attribute approach based on association rule mining of tourist preferences at scenic spots. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 26, 654–667 (2021).

Li, Y. & Cao, H. Prediction for tourism flow based on LSTM neural network. Procedia Comput. Sci. 129, 277–283 (2018).

Haris, E. & Gan, K. H. Extraction and visualization of tourist attraction semantics from travel blogs. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 10, 710 (2021).

Chunxiao, X. & Siying, G. Community characteristics and symbiotic mechanism of historical and cultural blocks: a case study of Taiping district in Changsha city. Geogr. Res. 42, 3313–3330 (2023).

Geng, S., Xing, Z., Wen, Z., Chengqiang, L. & Jie, C. Joint evaluation of the local and overall quality of commercial streets using multi-source data. Remote Sens. Inf. 36, 135–143 (2021).

Wei, W., Chunyu, W., Lin, M., Yaning, L. & Dawei, L. The influence of historical blocks on the city development: a case study of reconstructed Taiping Street in Changsha. Archit. J. 7, 18–21 (2010).

Hoffman, M., Bach, F. & Blei, D. Online learning for latent Dirichlet allocation. In Proc. 24th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 856–864 (2010).

Wallach, H. M., Murray, I., Salakhutdinov, R. & Mimno, D. Evaluation methods for topic models. In Proc. 26th Annual International Conference on Machine Learning, 1105–1112 (2009).

Rose, S., Engel, D., Cramer, N. & Cowley, W. Automatic keyword extraction from individual documents in Text Mining: Applications and Theory, 1–20 (Wiley, 2010).

Galdo, V., Li, Y. & Rama, M. Identifying urban areas by combining human judgment and machine learning: an application to India. J. Urban Econ. 125, 103229 (2021).

Bello, A., Ng, S.-C. & Leung, M.-F. A BERT framework to sentiment analysis of tweets. Sensors 23, 506 (2023).

Martilla, J. A. & James, J. C. Importance-performance analysis. J. Mark. 41, 77–79 (1977).

Schütze, H., Manning, C. D. & Raghavan, P. Introduction to Information Retrieval, Vol. 39 (Cambridge University Press, 2008).

Recuero-Virto, N. & Valilla Arróspide, C. Culinary destination enchantment: the strategic interplay of local gastronomy in regional tourism development. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 36, 100931 (2024).

Kolar, T. & Zabkar, V. A consumer-based model of authenticity: an oxymoron or the foundation of cultural heritage marketing? Tour. Manag. 31, 652–664 (2010).

Chen, C.-F. & Chen, P.-C. Resident attitudes toward heritage tourism development. Tour. Geogr. 12, 525–545 (2010).

Koo, S., Kim, J., Kim, C., Kim, J. & Cha, H. S. Development of an augmented reality tour guide for a cultural heritage site. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 12, 24 (2019).

Styliadis, A. D. et al. Metadata-based heritage sites modeling with e-learning functionality. J. Cult. Herit. 10, 296–312 (2009).

Lovell, J. Fairytale authenticity: historic city tourism, Harry Potter, medievalism and the magical gaze. J. Herit. Tour. 14, 448–465 (2019).

Rodzi, N. I. M., Zaki, S. A. & Subli, S. Between tourism and intangible cultural heritage. In Proc. 4th ASEAN Conference on Environment-Behaviour Studies (AcE-Bs), 411–420 (Elsevier, 2013).

Lak, A., Gheitasi, M. & Timothy, D. J. Urban regeneration through heritage tourism: cultural policies and strategic management. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 18, 386–403 (2020).

Gravari-Barbas, M. & Guinand, S. Tourism and Gentrification in Contemporary Metropolises: International Perspectives (Taylor & Francis, 2017).

Paiva, D. The paradox of atmosphere: tourism, heritage, and urban liveability. Ann. Tour. Res. 101, 103600 (2023).

Wang, Y., Hu, W., Park, K.-S., Yuan, Q. & Chen, N. Examining residents’ support for night tourism: an application of the social exchange theory and emotional solidarity. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 28, 100780 (2023).

Lu, J., Lai, I. K. W., Zhang, H., Liu, G. & Li, J. How can tourism be made engaging and meaningful? A measurement scale for ritual interaction. Tour. Manag. 103, 104900 (2024).

Jiang, Y. et al. Investigating spatial patterns and determinants of tourist attractions utilizing POI data: a case study of Hubei Province, China. Heliyon 10, e32370 (2024).

Wu, J., Lu, Y., Gao, H. & Wang, M. Cultivating historical heritage area vitality using urban morphology approach based on big data and machine learning. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 91, 101716 (2022).

Banerjee, I. Production of Railwayscape in urban environment: analysing railway heritage tourism potential in Siliguri City, India. Reg. Sustain. 4, 1–12 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Evaluating tourist perceptions of architectural heritage values at a world heritage site in south-east China: the case of Gulangyu Island. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 60, 127–140 (2024).

Yang, S. Q. et al. Sentiment classification of Chinese tourism reviews based on ERNIE-Gram plus GCN. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 20 (2022).

Yan, H., Liao, Q. & Xiong, H. The effect of emojis in travel experience sharing. Ann. Tour. Res. 107, 103798 (2024).

Wang, X. et al. How to perceive tourism destination image? A visual content analysis based on inbound tourists’ photos. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 33, 100923 (2024).

Zhao, Q. et al. Does location affect the mechanism of tourism competitiveness? Evidence from machine learning analysis. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 53, 101291 (2024).

Leong, A. M. W., Yeh, S.-S., Chen, H.-B., Lee, C.-L. & Huan, T.-C. Does gender make a difference in heritage tourism experience? Searching for answers through multi-group analysis. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 52, 101250 (2024).

Wang, Y. & Bai, H. The impact and regional heterogeneity analysis of tourism development on urban-rural income gap. Econ. Anal. Policy 80, 1539–1548 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: J.W. and W.F.; methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, and writing—original draft preparation: J.W.; data curation: J.W. and J.Y.; writing—review and editing: J.W.; visualization: J.W.; supervision: W.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions