Abstract

This study conducts a systematic review of 50 articles on virtual restoration of architectural heritage using the PRISMA framework. It proposes an integrated framework based on the analysis of technologies, methods, and platforms used across restoration stages. Future directions include expanding data sources and interdisciplinary integration, enhancing empirical validation, and exploring emerging technologies such as 4D restoration and AI-generated content to improve automation, intelligent reconstruction, and immersive restoration experiences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Architectural heritage (AH) embodies profound historical, cultural, and social values, and its preservation and restoration are of paramount importance for the transmission of human civilization. Against this backdrop, virtual restoration has emerged as a method that integrates advanced technologies with conservation objectives. By employing 3D modeling, image processing, and virtual reality (VR) technologies, virtual restoration enables non-invasive restoration of cultural heritage1. The 1995 “Virtual World Heritage” conference held in the United Kingdom marked a significant milestone in the research and development of virtual restoration technologies2. As technology has progressed, the role of virtual restoration in cultural heritage conservation has become increasingly prominent. In 2015, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) issued the Recommendation Concerning the Preservation of, and Access to, Documentary Heritage Including in Digital Form, which underscored the critical role of digital technologies in heritage preservation and transmission3. This guideline not only provided a policy framework for the protection of digital heritage but also catalyzed the application and innovation of virtual restoration technologies in the field of AH.

Virtual restoration, also referred to as simulated or digital restoration, has evolved and matured as a technical approach within this context. By integrating multilayered data of architectural artefacts—such as images, point clouds, and documentation—with traditional conservation techniques, virtual restoration leverages modern technologies including computer graphics, image processing, and virtual information. High-precision 3D models are used to restore the geometric shapes, textures, and structural details of buildings. These models are rendered through technologies such as VR, augmented reality (AR), and animation, generating interactive and visualized outputs4.

Prior research has offered valuable insights into virtual restoration for AH. For instance, Li et al.5 reviewed a novel research framework for the digital preservation of AH in the context of disaster cycles. Mendoza et al.6 conducted a systematic literature review analyzing the application of technologies in cultural heritage conservation and dissemination. Basu et al.7 systematically reviewed and investigated the use of machine learning, deep learning, and computer vision methods. Mansuri et al.8 identified research gaps in the integration of heritage conservation and building information modeling (BIM). Trillo et al.9 analyzed ten digital heritage platforms in Jordan and proposed optimized strategies for technology selection and implementation. Zhao10 used scient metric methods to analyze global BIM research trends, identifying key authors, institutions, hot topics, and research frontiers.

While these studies have advanced understanding of AH conservation and restoration across various dimensions, they primarily focus on specific technical applications or individual aspects of the field. A systematic integration of the complete workflow for virtual restoration of AH remains lacking. Key processes—including data collection, documentation, processing and interpretation, multidimensional reconstruction hypotheses, and visualization—have yet to be comprehensively mapped and interconnected. The absence of a holistic approach underscores the need for a systematic workflow framework for virtual restoration, addressing the requirements of integrity and coherence in heritage conservation practices. This research gap provides the entry point for the present study, which aims to fill this void and offer additional insights for virtual restoration practices.

To address the aforementioned gap, this study systematically reviews literature from the past decade to consolidate and analyze research findings and applications of virtual restoration in AH conservation. It proposes a systematic workflow framework to guide future developments in the field, offering theoretical insights and practical references.

The primary objectives of this study are as follows:

-

1.

To conduct a comprehensive analysis of virtual restoration for AH, including the geographical distribution of heritage sites, the countries involved, and the collaborative networks among co-authors.

-

2.

To analysis virtual restoration technologies on a phase-based basis, including the identification of specific technologies, methods, tools employed at each stage.

-

3.

To develop an integrated framework for the virtual restoration of AH, leveraging visual analysis to reveal the connections between workflows, research significance, and target users.

Methods

Data collection

A systematic review is a transparent and reproducible method that provides researchers with an effective approach to synthesizing scientific evidence and addressing specific research questions11 To ensure the scientific rigor and reliability of data collection, this study established strict inclusion and exclusion criteria based on predefined standards12. The literature search was completed on 26 April 2024, encompassing relevant research articles published between 2014 and 2024.

The primary data source for this study was the Scopus database. While both Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus are internationally recognized authoritative databases13, Scopus was chosen due to its broader coverage and notable multidisciplinary focus. It includes research not only in the natural sciences and engineering but also in the humanities, social sciences, architecture, and cultural heritage conservation—fields closely aligned with the objectives of this study14. This made Scopus particularly suited to supporting comprehensive retrieval of relevant literature for this research.

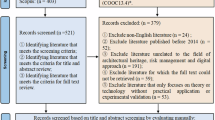

In addition, this study strictly adhered to the PRISMA 2020 guidelines15 for literature screening. Keywords including “cultural heritage” AND “Restor*” AND “techn*” were employed in the TITLE-ABS-KEY fields during the search. To avoid excluding critical works related to specific cultural heritage types, such as churches or museums, or particular technological applications, no specific terms such as “architecture,” “building,” or individual technologies were imposed. The wildcard keyword “Restor*” was used to target studies on hypothetical reconstructions or innovations in virtual restoration technologies, ensuring alignment with the study’s objectives and maintaining a comprehensive scope.

Virtual restoration technologies have undergone rapid development and widespread application over the past two decades16,17. However, this study focuses on literature from the past ten years (2014–2024) rather than a longer timeframe. This selection avoids outdated technologies and methods that may no longer be widely used, while accurately reflecting current research trends and technological advancements. A ten-year period provides a contemporary perspective on the field while covering the latest technological developments and key challenges in practice, thereby establishing a robust foundation for understanding the current state and future directions of virtual restoration technologies.

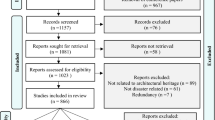

The specific process of literature screening is illustrated in Fig. 1, encompassing the stages of “identification,” “screening,” and “eligibility.” Ultimately, 50 articles met the inclusion criteria and were selected for systematic review and analysis.

Data analysis

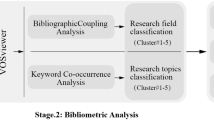

The 50 articles included in this study were systematically coded, and preliminary analysis was conducted using multiple visualization tools, including Datawrapper, VOSviewer v.1.6.18, and Scimago Graphica. This analysis focused on two dimensions: the geographical distribution of heritage sites and the regions of publication. These visualizations revealed the geographic characteristics and academic hotspots of research, providing contextual background for subsequent investigations.

Building on the universal analysis, this study further integrates the virtual restoration workflow proposed by Pietroni and Ferdani18 to systematically examine the specific technologies, methods, and software applications employed at five key stages of architectural virtual restoration. These findings offer data-driven insights that support the development of an integrated framework. Finally, through information visualization, the overall framework of architectural virtual restoration is analyzed and summarized. These visual outputs intuitively present the logical structure and critical components of the research, providing a reference pathway for a deeper understanding and practical application of virtual restoration in architectural heritage.

Results

Universal analysis

As shown in Table 1, the authors coded the 50 articles included in the review, identifying the cultural heritage sites and their respective countries.

Geospatial visualization (Fig. 2) reveals that most of the heritage sites studied are concentrated in Europe, with Italy and Spain serving as major contributors. This underscores Europe’s prominent role in research on virtual restoration for AH. Conversely, studies in Asia and other regions are relatively sparse, highlighting notable regional disparities in the adoption of virtual restoration technologies for AH. Such disparities may reflect differences in investment, research resources, and technological applications across regions.

The analysis conducted using VOSviewer v.1.6.18 and Scimago Graphica (Fig. 3) further illustrates international collaboration patterns in the field of virtual restoration technologies. Italy stands out with a highly centralized and dense collaboration network, forming core hubs of cross-national research alongside Spain, Portugal, and Romania. These tightly-knit networks have not only fostered innovation and development in virtual restoration but have also strengthened international collaboration in architectural heritage conservation.

By combining the global academic output and collaboration networks (Fig. 4a) with the distribution of global cultural heritage sites (Fig. 4b), this study reveals that academic research and collaboration on virtual restoration are concentrated in Europe, East Asia, and the Middle East. These regions attract significant attention due to their rich cultural heritage resources and serve as active centers of international academic collaboration and technological innovation. This distribution pattern suggests a strong correlation between the density of cultural heritage resources and research focus on virtual restoration technologies. Regions with abundant AH resources often emerge as focal points for research and application, offering valuable insights into global strategies for cultural heritage conservation.

a Global academic output and collaboration networks; b Global distribution of UNESCO world heritage sites (https://whc.unesco.org/en/wh-gis/).

Analysis of technological applications

This section systematically reviews and analyses the key techniques, methods, and tools (including equipment, software, or platforms) employed at five stages of virtual restoration for AH: Survey, Documentation, Data Processing and Interpretation, Creation of the Multi-Dimensional Reconstructive Hypothesis, and Source Mapping and Transparency The findings provide data-driven insights to support the development of an integrated framework for virtual restoration.

Stage 1: Survey

Figure 5 presents a statistical summary of data collection methods used during the survey stage, categorized into photogrammetry and scanning technologies. For instance, Article No. 40 utilized both aerial and ground photography to identify and classify pathological features of the Batalha Monastery19. The study further combined Structure-from-Motion Multi-View Stereo processing, Object-Based Image Analysis for automated classification, and infrared thermography to analyze surface damage to the building.

The review reveals that photogrammetry was employed more frequently than scanning, indicating its higher prevalence in relevant studies. Photogrammetry is further divided into ground-based and aerial photography (Table 2), while scanning technologies include laser scanning and radar scanning (Table 3). Additionally, some articles in the survey stage incorporated topographic surveys to collect environmental data. However, as this study focuses on the virtual restoration of AH, the statistical analysis is limited to photogrammetry and scanning technologies, without further discussion of topographic survey applications.

Photogrammetry

Photogrammetry is a foundational method for data collection in virtual restoration, valued for its broad applicability, ease of use, adaptability to various environments, flexibility, rapid and efficient data acquisition, relatively low cost, and highly extensible post-processing capabilities. As shown in Table 2, among 35 relevant studies, 15 employed aerial photography, while 31 used ground photography. Some studies combined both methods to achieve comprehensive documentation, ranging from macroscopic overviews to detailed micro-level features.

Aerial photography, facilitated by unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), offers a macroscopic perspective for documenting AH sites. Commonly used equipment includes DJI UAVs such as Yu-2pro, Inspire T600, Phantom 4 Pro, Phantom 3, S1000 eight-rotor, and Mavic Pro. These UAVs, equipped with high-resolution cameras, provide efficient site-wide environmental and structural feature capture through multiple flights. Their efficiency makes them suitable for documenting complex terrains or large-scale sites, offering a panoramic perspective essential for subsequent analyses.

While aerial photography excels in documenting overall site layouts, ground photography is indispensable for recording architectural details. Equipment used includes high-resolution cameras such as the Canon EOS 600D, Nikon D800E DSLR, Fuji X-T20, Panasonic DMC-TZ25, and Sony W830. These devices capture intricate details of surface decorations, textures, and internal structural elements, providing high-quality reference data for restoration and analysis. Lower-cost options such as the Canon EOS 600D SLR and Canon 450 SLR have been utilized in some studies, providing cost-effective solutions for ground photography.

In certain scenarios, smartphones (e.g., iPhone 11, Samsung Galaxy S7, Huawei Mate20) have been used as supplementary tools for quick documentation. While their resolution is lower than professional cameras, their portability and accessibility make them valuable for certain applications. Additionally, devices like the iPad Pro have been used for supplementary image capture in heritage environments, providing additional visual documentation.

Scanning

The choice of data collection methods during the initial survey stage of AH protection plays a key role in ensuring the scientific rigor and precision of restoration efforts. Among available methods, scanning technologies have become central to heritage documentation due to their high accuracy, non-invasive nature, and versatility. However, compared to photogrammetry, scanning technologies are less frequently adopted, possibly due to factors such as higher equipment costs, greater technical skill requirements, more complex and time-intensive data processing, and limited adaptability to certain conditions, such as rugged terrains or extreme weather. Additionally, one reason for this lower adoption is that photogrammetry retains natural color information, making data interpretation more intuitive, whereas laser scanning data lacks this visual information, requiring additional processing to reconstruct realistic textures.

This study systematically summarizes the applications of scanning technologies and associated equipment (Table 3) to provide insights for future data collection efforts in virtual restoration, particularly in high-precision mapping and complex structural modeling.

The findings indicate that laser scanning technologies are employed far more frequently than radar scanning during the scanning phase, reflecting their widespread application in AH surveying and modeling. Among these, terrestrial laser scanning is the most commonly used method due to its efficient data acquisition and adaptability to diverse environments. For instance, No.17 utilized the Leica BLK360 TLS and ZEB-REVO mobile laser scanner, successfully capturing high-precision 3D data of the Amezrou Synagogue20. Additionally, in the surveying of Corral del Carbón, Article No.46 combined the Leica BLK360 laser scanner and Leica TS02 total station21. The total station was used to establish reference coordinates for horizontal calibration, improve the registration accuracy of scan data, and assist in texture alignment in photogrammetry, contributing to enhanced geometric accuracy and texture quality of the model. Furthermore, 3D laser scanning has been employed in some studies due to its high-resolution modeling capability, which allows for comprehensive documentation of AH. This technology has proven particularly useful in reconstructing complex geometries and capturing large-scale architectural details, providing essential data for virtual restoration. However, the suitability of different technologies depends on specific research requirements, necessitating careful consideration of accuracy demands, environmental conditions, and data processing needs.

At the same time, mobile laser scanning has been utilized in certain studies to enhance flexibility and efficiency in data acquisition. For example, No.17 and No.43 employed ZEB-REVO for mobile scanning. Additionally, wearable mobile laser scanning has been used in specific scenarios requiring rapid measurements in complex environments, as demonstrated in No.3822. However, some studies (No.15, No.26, No.28, and No.50) mentioned the application of scanning technologies without specifying the exact methods used.

In contrast, radar scanning is relatively less prevalent in AH conservation. Although it offers advantages in detecting underground voids, buried components, and structural damage, its limited ability to capture surface details restricts its role in virtual restoration. For instance, ground-penetrating radar was used in No.36 and No.40 to analyze foundation stability and identify subsurface structures in AH19,23. While ground-penetrating radar remains a valuable supplementary tool in specific scenarios, its overall application in virtual restoration remains more limited compared to laser scanning technologies.

Stage 2: Documentation

The management of visual information during the documentation stage is one of the key components of the virtual restoration workflow for AH. Existing research on this stage primarily focuses on recording certain visual and textual information for AH restoration. This information not only provides critical data support for virtual restoration but also plays an irreplaceable role at various stages of the restoration process.

Despite the significant reliance on visual data in virtual restoration, only five of the 50 reviewed studies explicitly mention the documentation of visual information (Table 4). This phenomenon may be related to the rapid development of modern data acquisition technologies, which can directly generate digital data, rendering the documentation of visual information an “implicit” step. Consequently, issues such as standardized management, long-term storage, and cross-platform sharing of visual information are often insufficiently addressed in the literature. These shortcomings may limit the full utilization of visual information as a reliable reference resource in the restoration process.

In addition, researchers have highlighted the software and platforms used in managing visual information. Autodesk Revit and Cyclone software play crucial roles in image processing and information management. These tools support systematic archiving of collected photographs and other visual data, ensuring data integrity and accuracy. The ENEA It@cha Platform integrates visual information with other restoration data, offering users an immersive experience of cultural heritage sites while demonstrating high practical value in risk assessment. These platforms expand the application scenarios of visual information in cultural heritage conservation, enhancing the depth and breadth of virtual restoration efforts.

Tools like Excel and FileMaker Pro are used for encoding and describing both visual and textual data. Specifically, No.32 used Excel for the initial classification of collected architectural heritage data, standardizing and systematically organizing information from multiple sources24. This process facilitated the subsequent import into FileMaker Pro for database management, information visualization, and data retrieval, contributing to the accuracy, organization, and sustainability of heritage conservation efforts. By integrating multiple information sources, these tools support more efficiency and precise of information management. Notably, the Bundler file system excels in mapping correspondences between 3D coordinates and image pixels, providing technical support for data consistency and reliability.

Regarding the documentation of textual information, related studies are relatively scarce, with only two articles discussing this aspect in detail. Protégé software has been applied to construct knowledge graphs, enabling semantic annotation of various elements of AH. This enhances the systematicity and precision of information management, providing robust support for the semantic management of cultural heritage while laying a solid foundation for future research. Another study mentions that Excel and FileMaker Pro are not only used for managing visual information but also serve as tools for encoding and describing textual data. This multidimensional approach to data integration offers a clear and feasible pathway for managing complex information in virtual restoration workflows.

Stage 3: Data processing and interpretation

In the third stage of virtual restoration for AH, namely the Data Processing and Interpretation stage, research primarily focuses on three key areas: Data Alignment and Integration, Geometry and Texture Processing, and Semantic Information Processing. These areas involve the application of various techniques, software, and platforms to photo and scan data (Table 5). The findings indicate that Data Alignment and Integration is the central theme of current research, involving the effective merging of data from different sources and formats to ensure compatibility and consistency. The second major area is Geometry and Texture Processing, which emphasizes achieving high-precision visual restoration of architectural heritage. However, Semantic Information Processing is less frequently addressed in the literature, and its exploration remains in the early stages.

In the Data Alignment and Integration phase, 35 studies have extensively discussed the related technologies. In terms of photography data processing, Structure-from-Motion (SfM) is one of the predominant techniques, and Agisoft Metashape is among the most frequently used software tools. For example, in the City Walls of Pisa project described in Article No.2, researchers utilized SfM technology in combination with Agisoft Metashape to automatically detect photo data, match feature points, and calculate external camera parameters (position and angle), supporting the high-precision 3D reconstruction of architectural heritage25. Additionally, in image preprocessing, Photoshop was used to enhance image quality, while PTGui played a crucial role in panorama stitching and multi-view image alignment. In the domain of scan data processing, four studies mention the use of RMS Reprojection, the Totally Automated Co-registration and Orientation (TACO) Algorithm, the Simultaneous Localization and Mapping Algorithm (SLAM), and the GeoSLAM Algorithm, all of which play a significant role in improving point cloud accuracy and automated registration efficiency. Additionally, Faro Scene, Autodesk ReCap, and CloudCompare are widely employed for laser scan data processing, point cloud registration, and model optimization, highlighting their importance in scan data integration.

The Geometry and Texture Processing phase focuses on achieving high-precision visual restoration, with 12 studies addressing related research. In optimizing the geometry and texture of photographic data, some studies employed UV mapping and texture mapping techniques to enhance the detailed representation of AH surfaces. Additionally, several studies utilized software platforms such as Agisoft Metashape, Esri ArcGIS Pro, Maya, Substance Painter, and Photoshop to support the geometric and texture processing of AH. For scan data processing, some studies applied Triangulated Network techniques for geometric mesh generation, while others used the SIFT algorithm for feature matching and image registration to improve model accuracy and consistency. Among software tools, Cyclone and Autodesk Revit were used more frequently. For instance, No.4 employed Cyclone for site model stitching, exported the data in rcp format, and then imported it into Revit for data segmentation, measurement, and point cloud processing to provide geometric references for AH26. Overall, the integration of these technologies and tools not only enhances the geometric accuracy and texture detail of AH 3D reconstructions, making them more visually realistic, but also enriches the presentation of virtual restoration, laying a solid technical foundation for future conservation and research.

In the realm of Semantic Information Processing, while only six studies specifically addressed this topic, its importance is gradually gaining recognition in the academic community. Some studies employed semantic segmentation techniques, alongside the TagLab tool, for semantic processing of images. Additionally, 2D/3D semantic annotation and semantic segmentation became the main methods for processing scan data. For example, No.15 utilized the open-source software LabelMe to annotate damage on the scanned images of Wehrkirche Döblitz Church, enabling the tracking of surface deterioration over time27. These techniques support the semantic management of architectural components and spaces, laying the foundation for the future development of complex knowledge graphs. However, current research predominantly focuses on basic semantic annotation, lacking a comprehensive semantic information processing framework. This situation highlights the considerable potential for advancing semantic processing in cultural heritage digitization, underscoring the need for further exploration and refinement.

Stage 4: Creation of the multi-dimensional reconstructive hypothesis

In the Creation of the Multi-Dimensional Reconstructive Hypothesis stage, the digital reconstruction of AH primarily encompasses three aspects: Geometric Modeling, Semantic Modeling, and Dynamic and Temporal Dimension Modeling. Research in this phase highlights the application of diverse techniques and software in the virtual restoration of AH (Table 6).

Geometric modeling is a core research area in the digital preservation of AH, with 37 out of the 50 reviewed studies delving deeply into this topic. These studies underscore the importance of accurately restoring geometric forms for visualization and conservation, facilitating the precise recreation of complex structures and scenes while also providing scientific data for heritage studies. BIM and Heritage Building Information Modeling (HBIM) are widely adopted techniques in this field. While BIM is primarily applied to modern architectural digital modeling, HBIM focuses on reconstructing the intricate forms and details of historic buildings. In terms of software, tools such as Revit, Archicad, and AutoCAD are frequently used. For example, No.24 integrated BIM, HBIM, and Revit to digitally model and analyze the structure of Amman Citadel, enhancing the precision, visualization, and informatization of conservation and restoration efforts28.

Although semantic modeling was discussed in only two of the reviewed articles, its potential for development is significant. The primary goal of semantic modeling is to embed cultural context and historical information into digital representations of AH components and spaces. For example, Ontology-based Semantic Modeling (OSM) and the Semantic Annotation Framework (SAF) have been utilized in No.1 to organize architectural structural, material, and functional information using semantic web technologies29. By integrating CIDOC CRM and CRMdig, this approach establishes connections between architectural data, historical context, and conservation processes, thereby enhancing data sharing and interoperability.

Dynamic and temporal dimension modeling is an emerging field, with only one article discussing its application to AH conservation. This technique incorporates a timeline to simulate the evolution of AH over different historical periods. For instance, Article 43 utilized the JavaScript API Web and the 3D Heritage Online Presenter (3DHOP) platform to visually represent the historical transformations and degradation processes of certain heritage sites30. This approach introduces a dynamic perspective to heritage conservation, enabling models to display changes across various points in time.

Dynamic modeling holds significant value for academic research and public engagement. For example, virtual timelines can vividly depict the construction, expansion, and deterioration of architectural heritage, enhancing the audience’s understanding and interest in AH. This interactive presentation method has great potential for the education and dissemination of heritage knowledge, bridging the gap between the public and cultural heritage while raising awareness of its preservation.

Stage 5: Source mapping and transparency

In the Source Mapping and Transparency stage of AH conservation, research leverages various technologies and platforms to support multidimensional tasks in cultural heritage protection and presentation. The applications in this stage can be categorized into three main areas: Information Collaboration, Digital Documentation and Archiving, and Visualization and Display (Table 7).

Six studies highlight the importance of collaborative information management in AH conservation. Key tools include OpenTheso, the Atis Cloud Platform, Protégé Tool, and the integration of HBIM methodology with Business Process Management (BPM) systems. Current research in this field primarily focuses on WebGIS, thematic maps, semantic association engines, and AH restoration processes. For instance, Article No.48 explores the integration of HBIM and BPM using the Medieval Wall of Ávila in Spain as a case study, proposing a restoration process based on multi-source data fusion31. This study enhances the systematization and standardization of restoration workflows while improving the dynamic visualization of AH sites through multi-scale time-series data management. Additionally, it underscores the importance of collaborative information management in AH conservation by providing a platform for interdisciplinary cooperation and multi-stakeholder participation, ultimately improving transparency in information sharing.

Digital documentation and archiving represent another key area, emphasizing the systematic management, traceability, and sustainable use of archived heritage information. Seven studies have explored related applications, showcasing various digital tools and platforms, including HBIM, BIM, Autodesk Revit, PetroBIM, and GraphDB. These tools facilitate digital modeling, data management, and information integration, providing effective storage and access solutions for AH preservation. Research findings highlight multiple digital platforms and applications, such as OpenLab Applications, the As-built Model of HBIM, the Q-HBIM Platform, and Knowledge Graphs. These advancements drive the digital archiving, intelligent management, and interdisciplinary integration of AH information, offering valuable references for long-term monitoring and research in heritage conservation.

Visualization and display represent the most diverse area of technology applications in this stage, with 21 studies showcasing the potential of virtual technologies in cultural heritage presentation. Widely used tools include Unity, Pano2VR, WebGL API, Three.js, and Potree.js, which collectively support the creation of highly interactive digital environments for the immersive presentation of cultural heritage. In terms of outcomes, VR and AR applications are particularly prominent. These technologies offer diverse interactive formats that allow users to deeply engage with the spatial features and historical significance of cultural heritage. Notably, Article No.43 recommends that the Web 4D Viewer to enhance the visualization of temporal dimensions, vividly illustrating the dynamic changes in cultural heritage throughout its historical evolution30.

Such tools not only provide dynamic temporal data for academic research but also significantly enhance the appeal of heritage presentations. For instance, engaging content such as virtual flights, explorer diaries, and multi-use trails enables users to explore cultural heritage in varied and creative ways, fostering a deeper understanding and appreciation of its historical and cultural value.

Discussion

Integrated framework for virtual restoration of architectural heritage

Building upon the analysis presented in the preceding sections, this section systematically explores the workflow, target users, and research significance of virtual restoration for AH across five stages: Survey, Documentation, Data Processing and Interpretation, Creation of the Multi-Dimensional Reconstructive Hypothesis, and Source Mapping and Transparency. The study synthesizes these stages to construct an integrated framework for virtual restoration, offering a comprehensive perspective on its implementation and impact.

Virtual restoration workflow of architectural heritage

As shown in Supplementary Information 1, the stages of focus in each article have been marked. According to the results of this analysis, Stage 1 (Survey) and Stage 3 (Data Processing and Interpretation) are the most highly emphasized, indicating that these two stages play a central role in the field of AH virtual restoration research. Following this, Stage 4 (Creation of the Multi-Dimensional Reconstructive Hypothesis) and Stage 5 (Source Mapping and Transparency) are also given significant attention, while Stage 2 (Documentation) receives the least focus (Fig. 6).

It is noteworthy that Stage 3 is present in nearly all workflow combinations. Whether focusing solely on Stage 3 or integrating it into broader workflows, its inclusion consistently dominates. This highlights that data processing is not only a core component of AH virtual restoration research but also a crucial nexus linking and integrating the other stages. In contrast, Stage 2 receives relatively less attention. As an intermediary step, the findings from the Documentation phase often lack direct applicability, which may result in its insufficient emphasis and in-depth exploration in the reviewed literature.

As illustrated in Fig. 6, the combination of Stage 1, Stage 3, Stage 4, and Stage 5, as well as Stage 1, Stage 3, and Stage 4, received significant attention, with 12 articles addressing this workflow. The focus on Stage 1, Stage 3, Stage 4, and Stage 5 suggests that a multi-stage collaborative research approach is more suited to the complex demands of AH virtual restoration, emphasizing the importance of data acquisition, geometric modeling, hypothesis creation, and the transparency of outcomes. In comparison, the workflow comprising Stage 1, Stage 3, and Stage 4 places greater emphasis on the internal logic of technological implementation and process optimization. However, these studies paid less attention to the external dissemination and open discussions of the outcomes. This reflects the tendency, within technology-driven research, to delve deeper into the technical aspects of virtual restoration while neglecting the application needs of the target audience.

Furthermore, three articles focused on the combination of Stage 1, Stage 3, and Stage 5, emphasizing the coherence from preliminary investigation to data processing and outcome visualization to ensure the integrity and authenticity of the restoration work. Similarly, another four articles examined the workflow of Stage 1, Stage 4, and Stage 5, highlighting the interconnectedness of data collection, multi-dimensional hypothesis construction, and the visualization of results. These studies collectively suggest a greater focus on user interaction and the visual effects of the final output, demonstrating the potential value of virtual restoration in public education and heritage presentation. Moreover, three articles addressed the complete workflow of architectural virtual restoration, covering all stages to provide a comprehensive perspective on the process.

Meanwhile, three articles explored the workflow comprising Stage 1 and Stage 3, with a focus on optimizing the technologies and tools used for data acquisition and processing to improve the accuracy and efficiency of the restoration work. Another three articles concentrated on the data collection and modeling phases of Stage 1 and Stage 4. As the stages most likely to produce immediate, tangible outcomes, data collection and modeling are particularly suited to applications that require rapid generation of visualized models.

In contrast, the remaining workflow combinations received lower attention, with only one or two articles addressing them. This distribution suggests that researchers, based on their academic background and available resources, typically opt to concentrate on specific stages rather than attempting to cover the entire restoration workflow. Although Stages 1 through 5 together constitute a complete virtual restoration workflow, only three articles focus on the full process. This phenomenon may stem from the interdisciplinary depth required for full-process virtual restoration, involving the collaboration of fields such as history, architecture, computer science, and digital technologies. The coordination and integration of interdisciplinary teams often present significant challenges, which might lead researchers to prefer focusing on their own technical strengths and addressing specific workflow stages rather than attempting to encompass all aspects.

In conclusion, this research distribution reflects both the diversity of technological developments and the variety of application scenarios in the field of AH virtual restoration. It also highlights the challenges associated with constructing a comprehensive workflow, including resource constraints and collaborative difficulties. Future research could foster greater interdisciplinary collaboration and technological integration to advance the establishment of complete workflows, thereby offering more comprehensive and systematic solutions for AH conservation.

Workflow-user-significance association diagram of virtual restoration for architectural heritage

As shown in Supplementary Information 2, the authors systematically classified and analyzed the research significance target users of the 50 articles reviewed. The research significance is divided into five main categories: Significance 1: Educational & Public Engagement, Significance 2: Documentation & Preservation, Significance 3: Technological Development, Significance 4: Cost Control & Management, and Significance 5: Disaster Risk Management & Reconstruction.

The target users are categorized into expert users and non-expert users. The analysis reveals that 26 of the 50 articles address both expert and non-expert users, reflecting the researchers’ efforts to balance technical depth with practical applicability, thereby extending the multifaceted value and impact of their findings. Meanwhile, 24 articles focus solely on expert users, underscoring the field’s high dependence on professional expertise as a technology-intensive discipline.

As visualized in Fig. 7, the relationship between workflows, research significance, and target users was analyzed. The findings reveal that articles focusing on the workflow combination of Stage 1, Stage 3, Stage 4, and Stage 5 predominantly emphasize Educational & Public Engagement and Documentation & Preservation as their primary research significance. This dual focus highlights both the expectation for social impact from academic outcomes and the fundamental need for digital recording and representation of irreplaceable cultural heritage in restoration work.

For articles addressing the workflow combination of Stage 1, Stage 3, and Stage 4, the research significance is more diverse, spanning Educational & Public Engagement, Documentation & Preservation, Technological Development, and Cost Control & Management. This indicates that research in this area not only caters to academic and technological innovation but also integrates multidimensional goals of social dissemination and practical application. These varied research significances exemplify the collaborative evolution of theory and practice in cultural heritage restoration, balancing cultural communication, technological efficiency, and sustainable preservation.

Articles focusing on the workflow combination of Stage 1, Stage 4, and Stage 5 concentrate their research significance on Educational & Public Engagement, Documentation & Preservation, and Technological Development. This distribution demonstrates the field’s highly integrated and coordinated approach to social dissemination, scientific preservation, and technological innovation. It further indicates that cultural heritage restoration is gradually shaping into a multidimensional development pathway aimed at social value dissemination, underpinned by scientific preservation and driven by technological innovation.

Furthermore, articles that explore the workflow combination of Stage 1 and Stage 4 focus primarily on Documentation & Preservation and Disaster Risk Management & Reconstruction. This suggests that such workflows are more inclined to address the needs of emergency protection and long-term conservation. By applying virtual restoration technologies in disaster risk management, these studies enhance the protection and reconstruction potential of cultural heritage in the context of sudden disasters.

In contrast, other workflow combinations exhibit more singular focuses in terms of research significance, with only one or two articles addressing these aspects. This trend indicates that different workflow combinations vary significantly in their emphasis on target users and research significance. It not only reflects the diverse academic, practical, and societal demands within the field of virtual restoration for AH but also reveals the potential for future development in fostering more comprehensive research directions.

Conclusion

This study systematically reviewed literature on AH virtual restoration from 2014 to 2024 using the PRISMA framework, with in-depth analysis and synthesis conducted across three aspects: universal analysis, phased integration of virtual restoration technologies, and the development of an integrated framework for AH virtual restoration.

The analysis of geographical distribution and patterns of international collaboration revealed a notable imbalance. While Asia hosts a significant proportion of UNESCO World Heritage Sites, the region has comparatively fewer research outputs in the field of AH virtual restoration. This disparity underscores insufficient research investment and resource allocation in the region, highlighting the need for a more globally balanced development of cultural heritage virtual restoration technologies.

The phased integration of AH virtual restoration technologies revealed the interdisciplinary and multi-technical nature of this field. The convergence of diverse methodologies reflects an increasing reliance on and potential for innovation through multidisciplinary collaboration, laying a solid foundation for cross-disciplinary partnerships and technological integration in the future.

However, visualized workflow analysis indicates that only a limited number of studies encompass a complete virtual restoration workflow. This highlights the inherent complexity and uneven development of comprehensive workflows. On one hand, achieving a complete workflow necessitates the integration of knowledge across disciplines such as architecture, history, computer science, and digital technology. On the other hand, regional disparities in technological advancement further exacerbate the challenges in achieving a holistic workflow. These issues represent the primary challenges in current virtual restoration research.

Approximately half of the studies focus on expert users, reflecting the field’s reliance on professional expertise as a technology-intensive discipline. However, this emphasis potentially limits the application of virtual restoration in public education and social dissemination. Regarding research significance, practical needs such as disaster risk management and cost control are underexplored, suggesting an imbalance between theoretical exploration and practical application. The “workflow-user-significance” interactions reveal the diversity and directionality of virtual restoration research while exposing its limitations in integrating academic theory with societal practice.

Although this study provides a systematic review and analysis in the field of AH virtual restoration, it has certain limitations. First, as the study primarily relies on English-language literature indexed in the Scopus database, it does not fully encompass non-English publications. This may lead to the omission of important local studies from non-English-speaking countries, which could offer valuable insights into practical experiences and research methodologies. Second, from an applied perspective, the main contribution of this study lies in constructing a conceptual framework and summarizing technological trends. However, it has not yet been empirically validated in real-world heritage conservation projects. As a result, practical implementation of these findings may face challenges related to technological adaptability and operational feasibility. Additionally, given the rapid advancements in virtual restoration technologies for AH, with new tools and platforms constantly emerging, researchers are required to continuously track and adapt to these developments. Consequently, this study may not comprehensively capture the latest technological trends.

To address these limitations, future research should focus on several key areas to further advance AH virtual restoration. First, in terms of data collection, the scope of research should be expanded to include multiple databases, such as Web of Science and CNKI, while also incorporating more non-English literature, particularly studies from countries actively engaged in cultural heritage conservation. Second, regarding practical applications, empirical research should be strengthened to validate the proposed theoretical framework. Future studies could employ case studies or experimental projects to apply the integrated virtual restoration framework in real-world heritage conservation practices, assessing its effectiveness and feasibility across different architectural types, cultural contexts, and technological environments. Close collaboration with heritage management institutions, technology developers, and policymakers is essential to further refine the applicability of virtual restoration technologies and enhance their practical value.

Finally, given the rapid evolution of technologies in AH virtual restoration, future research should actively track and explore the potential applications of emerging technologies such as 4D restoration and AI-generated content (AIGC). The integration of these innovations could lead to breakthroughs in automated data processing, intelligent reconstruction, and immersive experiences, ultimately improving the sustainability and intelligence of heritage conservation. Therefore, maintaining a keen awareness of technological frontiers, fostering theoretical innovation, and bridging research with practical applications will be crucial to ensuring the feasibility and long-term development of virtual restoration technologies in the field of cultural heritage conservation.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- AH:

-

Architectural Heritage

- UNESCO:

-

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

- VR:

-

Virtual Reality

- AR:

-

Augmented Reality

- WoS:

-

Web of Science

- UAVs:

-

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles

- GPR:

-

Ground-Penetrating Radar

- SfM:

-

Structure-from-Motion

- TACO:

-

Totally Automated Co-registration and Orientation

- SLAM:

-

Simultaneous Localization and Mapping Algorithm

- HBIM:

-

Heritage Building Information Modelling

- OSM:

-

Ontology-based Semantic Modelling

- SAF:

-

Semantic Annotation Framework

- 3DHOP:

-

3D Heritage Online Presenter

- MR:

-

Mixed Reality

- BPM:

-

Business Process Management

References

Higueras, M., Calero, A. I. & Collado-Montero, F. J. Digital 3D modeling using photogrammetry and 3D printing applied to the restoration of a Hispano-Roman architectural ornament. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 20, e00179 (2021).

Zhang, Z., Zou, Y. & Xiao, W. Exploration of a virtual restoration practice route for architectural heritage based on evidence-based design: a case study of the Bagong House. Herit. Sci. 11, 35 (2023).

UNESCO Recommendation concerning the preservation of, and access to, documentary heritage including in digital form. https://www.unesco.org/en/legal-affairs/recommendation-concerning-preservation-and-access-documentary-heritage-including-digital-form (2015). Accessed 28 Nov 2024.

Hou, M. et al. Novel Method for Virtual Restoration of Cultural Relics with Complex Geometric Structure Based on Multiscale Spatial Geometry. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 7, 353 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. A review of the tools and techniques used in the digital preservation of architectural heritage within disaster cycles. Herit. Sci. 11, 199 (2023).

Mendoza, M. A. D., De La Hoz Franco, E. & Gómez, J. E. G. Technologies for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage—A Systematic Review of the Literature. Sustainability 15, 1059 (2023).

Basu, A. et al. Digital Restoration of Cultural Heritage With Data-Driven Computing: A Survey. IEEE Access 11, 53939–53977 (2023).

Mansuri, L. E. et al. A systematic mapping of BIM and digital technologies for architectural heritage. Smart Sustain Built Environ. 11, 1060–1080 (2022).

Trillo, C., Aburamadan, R., Mubaideen, S., Salameen, D. & Makore, B. C. N. Towards a Systematic Approach to Digital Technologies for Heritage Conservation. Insights from Jordan. Preserv. Digit Technol. Cult. 49, 121–138 (2020).

Zhao, X. A scientometric review of global BIM research: Analysis and visualization. Autom. Constr. 80, 37–47 (2017).

Lame, G. Systematic literature reviews: An introduction. Proc. Int. Conf. Eng. Des. ICED 1:1633–1642 (2019).

Nightingale, A. A guide to systematic literature reviews. Surgery 27, 381–384 (2009).

Zhang, D. et al. Study on sustainable urbanization literature based on Web of Science, scopus, and China national knowledge infrastructure: A scientometric analysis in CiteSpace. J. Clean. Prod. 264, 121537 (2020).

Harzing, A.-W. & Alakangas, S. Google Scholar, Scopus and the Web of Science: a longitudinal and cross-disciplinary comparison. Scientometrics 106, 787–804 (2016).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 88, 105906 (2021).

Papadopoulou, E. E. & Papakonstantinou, A. Combining Drone LiDAR and Virtual Reality Geovisualizations towards a Cartographic Approach to Visualize Flooding Scenarios. Drones 8, 398 (2024).

Acke, L., Corradi, D. & Verlinden, J. Comprehensive educational framework on the application of 3D technologies for the restoration of cultural heritage objects. J. Cult. Herit. 66, 613–627 (2024).

Pietroni, E. & Ferdani, D. Virtual Restoration and Virtual Reconstruction in Cultural Heritage: Terminology, Methodologies, Visual Representation Techniques and Cognitive Models. Information 12, 167 (2021).

Solla, M. et al. A Building Information Modeling Approach to Integrate Geomatic Data for the Documentation and Preservation of Cultural Heritage. Remote Sens. 12, 4028 (2020).

Matoušková, E., Pavelka, K., Smolík, T. & Pavelka, K. Earthen Jewish Architecture of Southern Morocco: Documentation of Unfired Brick Synagogues and Mellahs in the Drâa-Tafilalet Region. Appl. Sci. 11, 1712 (2021).

Reinoso-Gordo, J. F., Rodríguez-Moreno, C., Gómez-Blanco, A. J. & León-Robles, C. Cultural Heritage Conservation and Sustainability Based on Surveying and Modeling: The Case of the 14th Century Building Corral del Carbón (Granada, Spain). Sustainability 10, 1370 (2018).

Di Filippo, A. et al. Use of a Wearable Mobile Laser System in Seamless Indoor 3D Mapping of a Complex Historical Site. Remote Sens. 10, 1897 (2018).

Cozzolino, M, et al. Combined use of 3D metric surveys and non-invasive geophysical surveys for the determination of the state of conservation of the Stylite Tower (Umm ar-Rasas, Jordan). Ann. Geophys. https://doi.org/10.4401/ag-8060 (2019).

Fadli, F. & AlSaeed, M. Digitizing Vanishing Architectural Heritage; The Design and Development of Qatar Historic Buildings Information Modeling [Q-HBIM] Platform. Sustainability 11, 2501 (2019).

Giuliani, F., Gaglio, F., Martino, M. & De Falco, A. A HBIM pipeline for the conservation of large-scale architectural heritage: the city Walls of Pisa. Herit. Sci. 12, 35 (2024).

Chen, Y., Wu, Y., Sun, X., Ali, N. & Zhou, Q. Digital Documentation and Conservation of Architectural Heritage Information: An Application in Modern Chinese Architecture. Sustainability 15, 7276 (2023).

Taraben, J. & Morgenthal, G. Integration and Comparison Methods for Multitemporal Image-Based 2D Annotations in Linked 3D Building Documentation. Remote Sens. 14, 2286 (2022).

Al-Bayari, O. & Shatnawi, N. Geomatics techniques and building information model for historical buildings conservation and restoration. Egypt J. Remote Sens. Sp. Sci. 25, 563–568 (2022).

Moraitou, E. et al. Supporting the Conservation and Restoration OpenLab of the Acropolis of Ancient Tiryns through Data Modelling and Exploitation of Digital Media. Computers 12, 96 (2023).

Rodríguez-Gonzálvez, P., Guerra Campo, Á., Muñoz-Nieto, Á., Sánchez-Aparicio, L. & González-Aguilera, D. Diachronic Reconstruction and Visualization of Lost Cultural Heritage Sites. ISPRS Int. J. Geo. Inf. 8, 61 (2019).

Malagnino, A., Mangialardi, G., Zavarise, G. & Corallo, A. Process modeling for historical buildings restoration: an innovation in the management of cultural heritage. ACTA IMEKO 7, 95 (2018).

Lauro, V., Giovannangelo, M., De Riggi, M., Lanzaro, N. & Murtas, V. R.A.O. Project Recovery: Methods and Approaches for the Recovery of a Photographic Archive for the Creation of a Photogrammetric Survey of a Site Unreachable over Time. Heritage 6, 4710–4721 (2023).

Zhang, C., Deng, K., Yan, D., Mao, J. & Yang, X. Research on Multi-Source Image Fusion Technology in the Digital Reconstruction of Classical Garden and Ancient Buildings. Int. Rev. Spat. Plan Sustain. Dev. 11, 116–116 (2023).

Ortiz-Zamora, F. J. et al. Realidad aumentada aplicada a la recuperación del patrimonio histórico. DYNA-Ing.ía e Ind. 98, 86–90 (2023).

Abergel, V., Manuel, A., Pamart, A., Cao, I. & De Luca, L. Aïoli: A reality-based 3D annotation cloud platform for the collaborative documentation of cultural heritage artefacts. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 30, e00285 (2023).

Santini, S., Canciani, M., Borghese, V., Sabbatini, V. & Sebastiani, C. From Digital Restitution to Structural Analysis of a Historical Adobe Building: The Escuela José Mariano Méndez in El Salvador. Heritage 6, 4362–4379 (2023).

Karasaka, L. & Ulutas, N. Point Cloud-Based Historical Building Information Modeling (H-BIM) in Urban Heritage Documentation Studies. Sustainability 15, 10726 (2023).

Altadonna, A., Cucinotta, F., Raffaele, M., Salmeri, F. & Sfravara, F. Environmental Impact Assessment of Different Manufacturing Technologies Oriented to Architectonic Recovery and Conservation of Cultural Heritage. Sustainability 15, 13487 (2023).

Romanova, I. A. & Poluboyarova N. M. The Virtual Reconstruction of Historical and Cultural Heritage Monuments of the Vodyansky Settlement. Sci. Vis. https://doi.org/10.26583/sv.13.3.02 (2021).

Bruno, S. et al. VERBUM – virtual enhanced reality for building modelling (virtual technical tour in digital twins for building conservation). J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 27, 20–47 (2022).

Fiorini, G., Friso, I. & Balletti, C. A Geomatic Approach to the Preservation and 3D Communication of Urban Cultural Heritage for the History of the City: The Journey of Napoleon in Venice. Remote Sens 14, 3242 (2022).

Saura-Gómez, P., Spairani-Berrio, Y., Huesca-Tortosa, J. A., Spairani-Berrio, S. & Rizo-Maestre, C. Advances in the Restoration of Buildings with LIDAR Technology and 3D Reconstruction: Forged and Vaults of the Refectory of Santo Domingo de Orihuela (16th Century). Appl. Sci. 11, 8541 (2021).

Fanini, B., Ferdani, D. & Demetrescu, E. Temporal Lensing: An Interactive and Scalable Technique for Web3D/WebXR Applications in Cultural Heritage. Heritage 4, 710–724 (2021).

Lercari, N. et al. Building Cultural Heritage Resilience through Remote Sensing: An Integrated Approach Using Multi-Temporal Site Monitoring, Datafication, and Web-GL Visualization. Remote Sens. 13, 4130 (2021).

Grama, V. et al. Digital Technologies Role in the Preservation of Jewish Cultural Heritage: Case Study Heyman House, Oradea, Romania. Buildings 12, 1617 (2022).

Giuffrida, D. et al. The Church of S. Maria Delle Palate in Tusa (Messina, Italy): Digitization and Diagnostics for a New Model of Enjoyment. Remote Sens. 14, 1490 (2022).

Petrovič, D., Grigillo, D., Kosmatin Fras, M., Urbančič, T. & Kozmus Trajkovski, K. Geodetic Methods for Documenting and Modelling Cultural Heritage Objects. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 15, 885–896 (2021).

Pinti, L. & Bonelli, S. A Methodological Framework to Optimize Data Management Costs and the Hand-Over Phase in Cultural Heritage Projects. Buildings 12, 1360 (2022).

Giuffrida, D. et al. A Multi-Analytical Study for the Enhancement and Accessibility of Archaeological Heritage: The Churches of San Nicola and San Basilio in Motta Sant’Agata (RC, Italy). Remote Sens. 13, 3738 (2021).

Simou, S., Baba, K. & Nounah, A. The integration of 3D technology for the conservation and restoration of ruined archaeological artifacts. Hist. Sci. Technol. 12, 150–168 (2022).

Elhalawani, M. A., Zeidan, Z. M. & Beshr, A. A. A. Implementation of close range photogrammetry using modern non-metric digital cameras for architectural documentation. Geod. Cartogr. 47, 45–53 (2021).

Castán, M. Q. & Hernández, L. A. 3D survey and virtual reconstruction of heritage. The case study of the City Council and Lonja of Alcañiz. Vitr. Int. J. Arch. Technol. Sustain 6, 12–25 (2021).

Croce, V., Caroti, G., Piemonte, A. & Bevilacqua, M. G. From survey to semantic representation for Cultural Heritage: the 3D modeling of recurring architectural elements. ACTA IMEKO 10, 98 (2021).

Matrone, F. & Martini, M. Transfer learning and performance enhancement techniques for deep semantic segmentation of built heritage point clouds. Virtual Archaeol. Rev. 12, 73 (2021).

Vázquez de Ágredos Pascual, M. L. et al. 3D Model Acquisition and Image Processing for the Virtual Musealization of the Spezieria di Santa Maria della Scala, Rome. Heritage 5, 1253–1275 (2022).

Chen, S., Yang, H., Wang, S. & Hu, Q. Surveying and Digital Restoration of Towering Architectural Heritage in Harsh Environments: a Case Study of the Millennium Ancient Watchtower in Tibet. Sustainability 10, 3138 (2018).

Walmsley, A. P. & Kersten, T. P. The Imperial Cathedral in Königslutter (Germany) as an Immersive Experience in Virtual Reality with Integrated 360° Panoramic Photography. Appl. Sci. 10, 1517 (2020).

Soto-Martin, O., Fuentes-Porto, A. & Martin-Gutierrez, J. A Digital Reconstruction of a Historical Building and Virtual Reintegration of Mural Paintings to Create an Interactive and Immersive Experience in Virtual Reality. Appl. Sci. 10, 597 (2020).

Delegou, E. T., Mourgi, G., Tsilimantou, E., Ioannidis, C. & Moropoulou, A. A Multidisciplinary Approach for Historic Buildings Diagnosis: The Case Study of the Kaisariani Monastery. Heritage 2, 1211–1232 (2019).

Sestras, P. et al. Feasibility Assessments Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Technology in Heritage Buildings: Rehabilitation-Restoration, Spatial Analysis and Tourism Potential Analysis. Sensors 20, 2054 (2020).

Messaoudi, T., Véron, P., Halin, G. & De Luca, L. An ontological model for the reality-based 3D annotation of heritage building conservation state. J. Cult. Herit. 29, 100–112 (2018).

Nabiev, A. S., Nurkusheva, L. T., Suleimenova, K. K., Sadvokasova, G. K. & Imanbaeva, Z. A. Virtual Reconstruction of Historical Architectural Monuments: Methods and Technologies. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor Eng. 8, 3880–3887 (2019).

Bakhareva, O. & Kordonchik, D. Investments in preservation and development of regional cultural heritage: a library of BIM elements representing national architectural and urban-planning landmarks. Arch. Eng. 4, 39–48 (2019).

Turillazzi, B. et al. Heritage-led Ontologies: Digital Platform for Supporting the Regeneration of Cultural and Historical Sites. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 249, 307–318 (2020).

Andriasyan, M., Moyano, J., Nieto-Julián, J. E. & Antón, D. From Point Cloud Data to Building Information Modelling: An Automatic Parametric Workflow for Heritage. Remote Sens. 12, 1094 (2020).

Alsadik, B., Abdulateef, N. A. & Khalaf, Y. H. Out of Plumb Assessment for Cylindrical-Like Minaret Structures Using Geometric Primitives Fitting. ISPRS Int. J. Geo. Inf. 8, 64 (2019).

Martins, G. D., de Oliveira, H. C., de Gallis, R. A. B. & Vaz, D. V. Evaluation of Three-Dimensional Photogrammetric Model from Low-Cost Digital Camera Applied in the Cultural Heritage Registry. Anu. do Inst. Geocienc. 42, 338–348 (2019).

Portalés, C., Alonso-Monasterio, P. & Viñals, M. J. Reconstrucción virtual y visualización 3d del yacimiento arqueológico Castellet de Bernabé (Lliria, España). Virtual Archaeol. Rev. 8, 75 (2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Y.: literature search and screening, writing, methodology, information visualization; T.Q.: conceptualization, literature search and screening, information visualization and review; H.X.: literature screening, review, language and editing; S.B.: literature screening. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, Y., Tong, Q., He, X. et al. Exploring virtual restoration of architectural heritage through a systematic review. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 167 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01688-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01688-w

This article is cited by

-

A three-dimensional visualization model for intangible heritage of tie-dye handicrafts

npj Heritage Science (2025)