Abstract

Porcelain fragment classification is crucial for cultural relic restoration. Traditional manual methods relying on macroscopic features struggle to balance accuracy and efficiency. This study proposes a multi-channel graph convolutional network (GCN) architecture integrated with multi-directional Gaussian filtering. First, images are converted into graph structures and processed with multi-directional Gaussian filtering to reduce noise while preserving texture details. The proposed multi-channel GCN extracts rich interconnected features from multiple perspectives. Experimental results achieved 93.33% accuracy, outperforming ResNet50 by 3.33% and DenseNet121 by 2.80%. This approach effectively addresses noise interference and uneven feature distribution in microscopic images.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Porcelain stands as one of the great contributions of China to world civilization, characterized by a development history that is both long-standing and richly diverse. Over time, it has evolved into an extensive variety of types, each bearing witness to the technological advancements and transformations in artistic esthetics of ancient China. Moreover, porcelain reflects the social customs, religious beliefs, and philosophical thoughts prevalent during its creation. However, due to its inherent fragility, the number of intact porcelain fragments that have survived through the ages is limited. Particularly during archeological excavations of tombs, porcelain artifacts are often found shattered into fragments, with shards from different categories and even varying eras mixed together, thereby increasing the complexity of work for archeologists. Figure 1a illustrates a photograph taken during the excavation process at a particular site. The initial step in restoring these porcelain artifacts involves classifying the mixed fragments of porcelain. Porcelain from different kilns has unique features. For instance, Ding kiln is famous for its white porcelain1, using the upside-down firing method to create a tear-stained glaze. Its body contains kaolin, and the glaze is ivory-white, with sharp and flowing incised decoration. Compared to Xing kiln, Ding kiln’s white porcelain has better translucency, and the glaze surface shows bamboo comb marks. In the Southern Song Dynasty, Longquan kiln fired plum-green and powder-blue glazes using multi-layer glazing. The body contains purple gold clay, forming a cinnabar base. Jun kiln glaze often naturally forms thin2, winding cracks resembling worm trails. This happens because the glaze cracks at high temperatures and is later filled by subsequent glaze, a key feature for identifying official Jun ware from the Song Dynasty. The study of classifying microscopic images of Porcelain fragments is of great importance to cultural heritage conservation and archeological development. When it comes to the conservation of cultural heritage, analyzing the microscopic features of these fragments can be highly beneficial for the restoration of artifacts. Gliozzo’s research3 explored the reconstruction of firing processes by assessing the microstructure and mineral composition of unglazed porcelains, inferring the details of the original firing techniques through the microstructural analysis of ancient porcelains in order to restore artifacts. Regarding archeological development, since different dynasties had distinct types of porcelains and craft technologies, categorizing porcelain fragments can help determine the period of a site. Moreover, the microstructural characteristics of porcelain fragments, such as bubble distribution and crystal morphology4, can offer a scientific basis for identifying kiln sites. Traditional classification of porcelain shards heavily depended on expert observations based on experience, such as evaluating the luster, color, and texture of the porcelain glaze through visual inspection. However, with the progress of technology, modern archeology has incorporated more advanced technical means to assist in identification and research.

Recent advances in analytical methodologies have expanded the toolkit for material characterization. Comprehensive reviews of hyperspectral image classification5 highlight the growing role of deep learning in processing complex spatial-spectral relationships, while lightweight architectures like Xcep-Dense6 demonstrate efficient feature extraction through extreme inception modules. These developments provide valuable insights for addressing similar challenges in porcelain analysis.

Chemical composition analysis represents one of the primary methodologies7 employed in the study of ancient porcelain both domestically and internationally. Techniques such as X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy8, proton-induced X-ray emission spectroscopy9, and Raman spectroscopy10 are widely utilized to determine the elemental composition and mineral structure of porcelains. These methods provide crucial information about the source of raw materials, aiding in identifying the production site or kiln and offering evidence for dating11. Furthermore, radiometric dating techniques like thermoluminescence11 and optically stimulated luminescence12 are used to estimate the age of the porcelain. Despite their effectiveness in compositional analysis, these methods typically cannot delve into the microscopic level to analyze the glaze structure of porcelain. The glaze structure, a micro-characteristic that encompasses details such as glaze layer thickness, crystal distribution, bubble density, and shape, plays a critical role in distinguishing between different types of porcelain shards. To address this limitation, microscopic analytical techniques have increasingly become important tools for studying the glaze structure of porcelain. Recent innovations in 3D-convolutional autoencoders13 and spectral-spatial generative adversarial networks14 have shown remarkable success in capturing hierarchical features from complex microstructures, suggesting promising directions for porcelain glaze analysis. Figure 1b presents the structure of porcelain fragments under an optical electron microscope, allowing for a clear observation of the size and distribution characteristics of bubbles within the shards. Therefore, if we can capture the distinctive characteristics of different categories of porcelain shards from these microscopic images, we will be able to achieve more accurate and scientifically rigorous classification results.

In recent years, advancements in computer vision and machine learning have given rise to numerous methods for image classification. In the fields of cultural heritage and archeology, deep learning has been successfully applied to porcelain classification, significantly improving accuracy and efficiency. For instance, Zhou et al.15 proposed a CNN-based method for porcelain microscopic image classification, using a multi-scale fusion bottleneck structure and chunking attention mechanism to better identify complex micro-features. Ling et al.16 reviewed 22 empirical studies on machine-learning-based ancient porcelain classification, noting a growing trend in the use of deep learning algorithms, which offer advantages in feature extraction and classification accuracy. Wang et al.17 classified the provenance of archeological porcelain using microscopic imaging and ensemble deep learning, constructing a porcelain microscopic image dataset and employing three deep learning architectures for efficient classification. Zhuang et al.18 introduced a method combining multi-scale fusion bottleneck structures and chunking attention mechanisms, enhancing classification accuracy for porcelain microscopic images. Most classification models are based on convolutional neural networks19,20, such as ResNet5021, VGG1622, and DenseNet12123. These models usually leverage translational invariance and sliding window strategies to sequentially extract features from images. Comparative studies on limited sample scenarios24 reveal that conventional CNNs struggle with spatially heterogeneous features, motivating the exploration of alternative architectures like graph neural networks. However, some characteristic information of porcelain fragment microscopic images (PFMIs) is often unevenly distributed and requires multifactorial correlation for effective classification. Figure 2 illustrates the process of constructing a graph structure from a two-dimensional image. In this graph structure, various parts of the image can be connected to form a network of nodes and edges. Each node represents a feature region within the image, while the edges denote the relationships between these regions. The constructed graph structure can more accurately capture the complex relationships between feature regions. The method proposed by Todescato et al.25, based on multi-scale patch-based feature graphs (MPFG), improves image classification by creating multi-scale feature maps and encoding them with graph convolutional networks (GCNs), considering features at different scales and capturing spatial relationships between image regions through a graph structure. The Vision GNN architecture proposed by Han et al.26 represents images as graph structures and uses graph neural networks for information exchange and feature transformation among nodes (image patches), offering a new approach for image classification by effectively handling irregular and complex objects in images.

Additionally, the presence of noise in the microscopic images is inevitable and can impact the classification results. Cross-domain semi-supervised approaches27 and autoencoder-enhanced frameworks28 have demonstrated robust noise suppression capabilities in related domains, providing methodological references for our work.

To this end, we propose MCMG, a multi-channel graph convolutional network (MGCN) with a multi-directional Gaussian filter (MDGF). A key step in using graph structures for classification is to construct a graph from the image. Commonly, each pixel is defined as a node in the graph29,30, and edges are constructed based on spatial relationships between pixels. However, this method is computationally intensive. An alternative approach employs superpixel segmentation31,32 to divide the image into multiple superpixel regions, with each superpixel serving as a node. This reduces the number of nodes and significantly lowers computational complexity. However, the quality of superpixel segmentation can affect the final results. Therefore, we segment the porcelain fragment's microscopic images into N non-overlapping patches to construct a graph with these patches as nodes. Through this method, we can leverage the characteristics of graph structures to associate features of different regions of the image and pass information through edges between nodes.

We utilize a multi-channel graph convolutional structure to extract features from the graph. Different graph convolution methods can extract features from multiple perspectives, and combining the results from different channels yields richer feature information. This multi-stream strategy draws inspiration from feature fusion techniques in deep Siamese networks33, where hybrid architectures effectively combine handcrafted and learned representations. In addition, by combining Gaussian filters with different directions, we can reduce image noise while enhancing texture details. We conducted experiments on the PFMI dataset, where MCMG achieved an accuracy of 93.33%, which is 3.33% higher than ResNet50, 2.66% higher than VGG16, 2.67% higher than ViG, and 0.53% higher than DenseNet121. and 0.38% higher than MPFG. We also performed a series of ablation experiments to validate the effectiveness of our method.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

(1)

We propose a method for the classification of PFMIs, termed MGCN with multi-directional Gaussian filter (MCMG). This method achieves multifactorial feature association by constructing graphs from the images. It utilizes a multi-channel GCN to extract features from multiple perspectives and applies a multi-directional Gaussian filter to reduce noise and enhance texture features in the microscopic images.

-

(2)

We constructed the PFMIs dataset and validated the proposed method on this dataset. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method outperforms traditional classification models in the classification of PFMIs.

Method

Overall framework

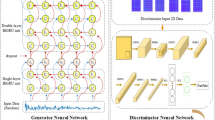

The MCMG primarily consists of two modules: the multi-directional Gaussian filter (MDGF) module and the MGCN. Figure 3 illustrates the overall structure of MCMG. Specifically, in the MDGF module, the input image is filtered using a series of Gaussian filters rotated in different directions. For each pixel, the convolution result corresponding to the direction with the highest response value is selected as the final output. This module aims to reduce noise and enhance texture in the input image. In the MGCN, the network receives a graph with N nodes as input. This graph is constructed by dividing the output of the MDGF module into N non-overlapping patches and extracting features from them. The graph is processed through C graph convolutional channels, and their outputs are aggregated before being passed to the Triplet-Attention34, which adds attention mechanisms and outputs the results. In this module, by aggregating the results from multiple graph convolutional methods, the model can extract feature information from different aspects.

Multi-directional Gaussian filter module

In image processing, Gaussian filtering is a common smoothing technique used to reduce noise in images. The standard Gaussian filter kernel, g(x, y), is a two-dimensional Gaussian function, with the formula as follows:

Traditional Gaussian filters35,36 smooth features in all directions when processing images. This means they uniformly reduce noise in the image but can also blur important directional features such as edges or textures. To address this, we propose the MDGF module.

The MDGF module captures texture features by applying a Gaussian filter in multiple directions. Specifically, we can rotate the base Gaussian filter Nd times to obtain a set of directional Gaussian filters \(K\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{N}_{d}\times C\times m\times m}\), where m is the size of the filter. For each direction d, we compute the corresponding Gaussian filter \({g}_{{\theta }_{d}}(x,y)\) (as shown in Equation (2)) and construct its matrix form kd, where \({\theta }_{d}=\frac{2\pi d}{{N}_{d}}\), and \(x^{\prime}\) and \(y^{\prime}\) are the rotated coordinates.

Next, we apply each directional Gaussian filter kd to the input image \(X\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{B\times C\times H\times W}\) through a convolution operation, obtaining the convolution result Yd = Conv2D(X, kd). During this process, each directional Gaussian filter performs noise reduction in its respective direction. Subsequently, we combine the convolution results from different directions into a single output \(Y=\max ({Y}_{0},{Y}_{1},\ldots ,{Y}_{{N}_{d}-1})\), retaining the maximum response value for each pixel. Since noise is randomly distributed, while texture features have a certain directionality, by retaining the maximum response values across all directions, we can enhance these directional features, thereby preserving and enhancing texture features.

Graph construction

After enhancing the texture features through the MDGF module, we construct a graph representation from the processed feature map to capture complex spatial and structural relationships. The feature map is divided into a set of non-overlapping patches of size H × W × C, where each patch is vectorized into a feature vector \({{\bf{x}}}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d}\) such that d = H × W × C. These vectors form a feature matrix \(X=[{{\bf{x}}}_{1},{{\bf{x}}}_{2},\ldots ,{{\bf{x}}}_{N}]\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d\times N}\), defining the node set V = {v1, v2, …, vN}, where each node vi corresponds to a patch’s feature representation. To establish edges between nodes, we use the K-nearest neighbors (KNN) algorithm. For each node vi, pairwise Euclidean distances to all other nodes are computed as

The KNN of vi are selected to form N(vi). Directed edges eji are created from each neighbor vj ∈ N(vi) to vi, resulting in an adjacency matrix \(A\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{N\times N}\) defined by

The final graph structure is G = (V, E), where E = {(vj, vi)∣Aji = 1}. This formalizes the graph construction as G = G(X), explicitly linking the graph topology to the input feature matrix. This approach transforms the enhanced feature map into a structured graph representation, enabling subsequent analysis to leverage both local texture patterns encoded in patches and global structural dependencies captured via KNN-based edges.

Multi-channel graph convolutional network

The constructed graph G is input into the MGCN module, as illustrated in Fig. 4. Specifically, the graph G undergoes processing through c ∈ [1, 2, …, C] different graph convolution methods Fc( ⋅ ). Taking the maximum relative graph convolution as an example, the graph convolution operation can be formalized as follows:

Here, Wagg and Wupdate are the learnable weights in the aggregation and update operations, respectively. F(G, W) represents the entire graph convolution process. The functions \({\mathcal{A}}\) and \({\mathcal{U}}\) correspond to the aggregation and update steps in the graph convolution, respectively.

More specifically, the aggregation operation calculates the representation of each node xi by collecting the features of its neighboring nodes. For each node xi and its neighboring node set N(xi), we perform aggregation using the maximum relative difference:

This step captures the most significant differences between the node and its neighbors, and combines this information with the node’s own features.

Next, the update operation further processes the aggregated features. New node feature representations are generated through linear transformation and activation functions:

Here, σ is the activation function, and b is the bias term. To extract features from different perspectives, we introduce multiple graph convolution methods that complement the maximum relative graph convolution and enrich the model’s feature representation from multiple dimensions. For example:

-

Max-Relative GraphConv (MR)37: this method emphasizes local contrast information, focusing on the relative feature differences between nodes and their neighbors.

-

Graph Isomorphism Network (GIN)38: it transforms node features through a multi-layer perceptron and combines the adjacency matrix to maintain isomorphism invariance, which helps capture the similarity and heterogeneity between nodes.

-

GraphSAGE (SAGE)39: it adopts an aggregation strategy, gathering information from neighbors to update node features, making it suitable for large-scale graph datasets.

-

EdgeConv (EDGE)40: it focuses on information transfer along edges, allowing the model to learn the dynamic changes in node interactions, and is suitable for capturing data features in non-Euclidean spaces such as point clouds.

We leverage this diversity to enrich the model’s expressiveness by combining the results from all channels. Specifically, as shown in formula (8), the final feature matrix Zout is obtained through matrix concatenation, integrating the advantages of various graph convolution methods to form a comprehensive and multi-level feature representation.

Subsequently, Zout is fed into the Triplet-Attention module. This module not only captures cross-dimensional dependencies through rotation operations and residual transformations but also enhances the effectiveness of the attention mechanism, ensuring that the model focuses on the most relevant features while introducing minimal computational overhead.

Result

Dataset

We used the RX-100 ultra-depth 3D digital microscope produced by Horix Corporation in Japan to capture the microstructure of different kinds of porcelain relic fragment samples collected by the laboratory. Figure 5 shows some relic fragment samples and data acquisition equipment. We built the PFMIs dataset with 200 magnification. This dataset consists of 2000 microscopic images, categorized into 20 groups based on porcelain relic fragment types, as shown in Fig. 6. The ultra-depth 3D digital microscope can capture tiny details and microstructures of samples, providing important data support for scientific research. The PFMI datasets can be used for tasks such as porcelain fragments intelligent classification, virtual restoration, authenticity identification, dynastic analysis, kiln mouth judgment, etc, which provide a new perspective for the restoration, analysis, and identification of porcelain cultural relics in the field of archeology.

Experimental setting

We use accuracy as the evaluation criterion for our method. All models were trained using the AdamW41 optimizer, with an initial learning rate set to 2 × 10−3, for a total of 300 epochs. The weight decay was set to 0.05, and the batch size was 16. Additionally, all models incorporated random erasing42 with a probability of 0.25. To ensure that the learning rate smoothly decays during training, we employed the cosine annealing strategy43 as the learning rate scheduler. For data preprocessing. In the image segmentation phase, all images were divided into 14 × 14 patches for graph construction. In the process of building these graphs, we utilized a KNN algorithm with k = 9. In the final feature transformation module, composed of fully connected layers, the number of modules is 6. For the Multi-Channel Graph Convolution component, we utilized 4 types of graph convolution methods: EdgeConv (EDGE), Max-Relative GraphConv (MR), Graph Isomorphism Network (GIN), and GraphSAGE (SAGE). Our network implementation was carried out using the PyTorch framework, and all models were trained on two NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPUs.

Comparison with the SOTA methods

In order to verify the effectiveness of the proposed MCMG, we compared the proposed method with ResNet50, VGG16, DenseNet121, and ViG. The results, as shown in Table 1, indicate that our method achieved an accuracy of 93.33%, which is 3.33% higher than ResNet50, 2.67% higher than ViG, 2.66% higher than VGG16, 0.53% higher than DenseNet121, and 0.38% higher than MPFG.

Experimental results show that our MCMG architecture outperforms other models in porcelain microscopic image classification.ResNet50, VGG16, and DenseNet121 are CNN-based models. They mainly use translation invariance and sliding window strategies to capture spatial features, but have difficulty in capturing the complex features associated with different regions of an image. ViG and MPFG are GCN-based models. Although they can capture global image features using graph convolutions, their single graph convolution method cannot fully and effectively mine key information from the complex features of porcelain microscopic images. In practical porcelain microscopic images, noise is a key factor affecting classification accuracy. For example, imaging system noise and diffraction can cause random interference. This can mask or blur details like bubble edges and crystal shapes, making classification harder. Also, noise may lead models to learn wrong feature patterns during training, further reducing classification reliability. Our MCMG architecture uses multi-directional Gaussian filters to reduce noise and enhance texture details. It also uses an MGCN to capture complex relationships between feature regions from different angles. These features make our method more suitable for classifying porcelain microscopic images.

Ablation study

The effectiveness of MDGF and MGCN

To verify the effectiveness of MDGF and MGCN, we conducted a series of ablation experiments. As shown in Table 2, the experimental results indicate that removing MDGF alone results in a 1.33% decrease in accuracy compared to MCMG. Removing MGCN while retaining single-channel MR leads to a 0.83% decrease in accuracy. When both MDGF and MGCN are removed while retaining single-channel MR, the accuracy decreases by 1.50%. These results demonstrate that both MDGF and MGCN enhance the model’s classification accuracy, with the best performance achieved when both modules are included together.

The effectiveness of the number of channels

In the MGCN part of our method, we can enhance model performance by fusing multiple channels. To explore the impact of the number of channels on model performance, we conducted hyperparameter experiments with different channel settings. The experimental results are shown in Table 3. We selected 4 different convolution methods: Max-Relative GraphConv37 (MR), Graph Isomorphism Network (GIN)38, GraphSAGE39 (SAGE), and EdgeConv40 (EDGE).

The experimental results demonstrate that increasing the number of channels from 1 to 4 gradually improved the model’s classification performance, achieving an accuracy of 93.33% at 4 channels. This enhancement may be attributed to the MGCN’s effective utilization of features from various perspectives, which integrates information from additional channels to boost classification accuracy.

The effectiveness of the number of directions

To evaluate the effect of varying the number of Gaussian filter directions in the MDGF on our method’s performance, we conducted a systematic hyperparameter search. Within the MDGF module, we modified the number of filter directions to assess its impact on the accuracy of our method. The experimental results are shown in Fig. 8a.

From the figure, it can be observed that as the number of directions increases, the model’s accuracy initially improves significantly, reaching a peak of 93.33% at 16 directions. However, when the number of directions increases to 24, the model’s accuracy decreases. This indicates that moderately increasing the number of directions helps in extracting richer features, but an excessive number of directions (such as 24) may lead to performance degradation, possibly due to unnecessary complexity causing overfitting or other issues.

Visualization

To better understand the classification capabilities and performance of our method, we conducted a visualization analysis using heatmaps and t-SNE44 plots.

The heatmaps were constructed using the Grad-CAM45 method. We compared our method trained on the PFMI dataset with the pre-trained models VGG16 and ResNet50 on the ImageNet dataset. The visualization results (as shown in Fig. 7) indicate that our method performs better in capturing the edges of bubbles in PFMIs and extracts features from a broader area. Additionally, our method demonstrates stable feature extraction across different categories of porcelain fragments, even for those with subtle visual features. In contrast, VGG16 and ResNet50 focus primarily on the bubbles, with more concentrated feature extraction regions, and their extraction capability varies significantly across different types of PFMIs. The differences in visualization between MCMG and other classification models stem from two main factors. First, MCMG uses a multi-directional Gaussian filter for noise reduction and texture detail enhancement in input images. This helps the model focus precisely on crucial features like bubble edges and textures in microscopic images. Models without this processing are prone to noise interference, leading to unstable feature extraction. Second, unlike traditional CNNs relying on translation invariance and sliding window strategies, MCMG constructs a graph structure to capture complex relationships between different image regions. This allows for a deeper understanding of feature context and associations, enabling the model to cover a broader area. Each color in Fig. 8b represents a category, and the position of the points reflects the similarity between samples. The figure shows that our method can effectively classify different types of PFMIs.

Discussion

This study proposes an MGCN with multi-directional Gaussian filtering (MCMG) for PFMI classification. The framework employs two core components: the MDGF for simultaneous noise suppression and directional texture enhancement; and the MGCN that aggregates features through heterogeneous topological modeling. Experimental validation on the PFMI dataset confirms the method’s effectiveness in porcelain microscopic image classification.

Notably, the framework demonstrates cross-domain adaptability: the configurable directional parameters in MDGF show potential for medical image enhancement tasks such as tumor boundary detection, while MGCN’s structural modeling capability exhibits transferability to material microstructure characterization. Current limitations primarily stem from computational complexity in graph construction and parallelized graph convolution operations, which constrain real-time deployment in field applications like archeological onsite analysis. Future work will prioritize (1) optimized graph construction through sparse connectivity patterns and (2) adaptive channel selection mechanisms.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- GCN:

-

graph convolutional network

- MCMG:

-

Multi-Channel graph convolutional network with Multi-directional Gaussian filter

- MDGF:

-

multi-directional gaussian filter

- MGCN:

-

Multi-channel Graph Convolutional Network

- PFMI:

-

porcelain fragment microscopic images

- t-SNE:

-

t-Distributed stochastic neighbor embedding

- Grad-CAM:

-

gradient-weighted class activation mapping

- SOTA:

-

State of the art

References

Huang, E. Chinese ceramics: from the Paleolithic period through the Qing Dynasty ed. by Li Zhiyan, Virginia Bower, and He Li. China Rev. Int. 19, 291–292 (2012).

Wood, N. Chinese glazes: Their Origins, Chemistry, and Recreation (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999).

Gliozzo, E. Ceramic technology. How to reconstruct the firing process. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 12, 260 (2020).

Ren, Z. et al. Study of sauce glazed wares from Yaozhou Kilns (Northern Song Dynasty, 960–1127 CE): probing the morphology and structure of crystals in the glazes. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 42, 7352–7359 (2022).

Ranjan, P. & Girdhar, A. A comprehensive systematic review of deep learning methods for hyperspectral images classification. Int. J. Remote Sens. 43, 6221–6306 (2022).

Ranjan, P. & Girdhar, A. Xcep-dense: a novel lightweight extreme inception model for hyperspectral image classification. Int. J. Remote Sens. 43, 5204–5230 (2022).

Nigra, B. T., Faull, K. F. & Barnard, H. Analytical chemistry in archaeological research. Anal. Chem. 87, 3–18 (2015).

Pillay, A., Punyadeera, C., Jacobson, L. & Eriksen, J. Analysis of ancient pottery and ceramic objects using X-ray fluorescence spectrometry. X Ray Spectrom. Int. J. 29, 53–62 (2000).

Dasari, K., Acharya, R., Ray, D. & Lakshmana Das, N. Application of PIXE for the determination of transition elements in the grouping study of archaeological clay potteries. X Ray Spectrom. 46, 180–185 (2017).

Medeghini, L., Lottici, P. P., De Vito, C., Mignardi, S. & Bersani, D. Micro-raman spectroscopy and ancient ceramics: applications and problems. J. Raman Spectrosc. 45, 1244–1250 (2014).

Galli, A., Sibilia, E. & Martini, M. Ceramic chronology by luminescence dating: how and when it is possible to date ceramic artefacts. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 12, 1–15 (2020).

Feathers, J. K., Holliday, V. T. & Meltzer, D. J. Optically stimulated luminescence dating of southern high plains archaeological sites. J. Archaeol. Sci. 33, 1651–1665 (2006).

Ranjan, P., Kumar, R. & Girdhar, A. A 3D-convolutional-autoencoder embedded siamese-attention-network for classification of hyperspectral images. Neural Comput. Appl. 36, 8335–8354 (2024).

Ranjan, P., Girdhar, A., Ankur & Kumar, R. A novel spectral-spatial 3d auxiliary conditional GAN integrated convolutional LSTM for hyperspectral image classification. Earth Sci. Inform. 17, 5251–5271 (2024).

Mingquan, Z., Jiatong, L., Long, F., Zhenghan, L. & Yangyang, L. Microscopic images of ceramic relics fragments classification method based on dual channel attention mechanism and comparative learning. In Proc. International Conference on Optics and Machine Vision 13179, 315–323 (SPIE, 2024).

Ling, Z., Delnevo, G. & Mirri, S. Finding on machine learning approaches for classification of ancient ceramics—a systematic literature review, 19 October 2023, PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square.

Wang, Q., Xiao, X. & Liu, Z. Using microscopic imaging and ensemble deep learning to classify the provenance of archaeological ceramics. Sci. Rep. 14, 32024 (2024).

Zhuang, Z., Xu, X., Xia, X., Li, Y. & Zhang, Y. Ceramic microscope image classification based on multi-scale fusion bottleneck structure and chunking attention mechanism. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 15, 1120-1136 (2024).

Lee, H. & Kwon, H. Going deeper with contextual CNN for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 26, 4843–4855 (2017).

Wang, J. et al. CNN-RNN: a unified framework for multi-label image classification. In Proc. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2285–2294 (2016).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proc. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 770–778 (2016).

Karen, S. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv: 1409.1556 (2014).

Huang, G., Liu, Z., Van Der Maaten, L. & Weinberger, K. Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proc. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 4700–4708 (2017).

Ranjan, P. & Girdhar, A. A comparison of deep learning algorithms dealing with limited samples in hyperspectral image classification. In Proc. 2022 OPJU International Technology Conference on Emerging Technologies for Sustainable Development (OTCON) 1–6 (IEEE, 2023).

Todescato, M. V., Garcia, L. F., Balreira, D. G. & Carbonera, J. L. Multiscale patch-based feature graphs for image classification. Expert Syst. Appl. 235, 121116 (2024).

Han, K., Wang, Y., Guo, J., Tang, Y. & Wu, E. Vision GNN: an image is worth graph of nodes. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 8291–8303 (2022).

Ranjan, P. & Gupta, G. A cross-domain semi-supervised zero-shot learning model for the classification of hyperspectral images. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 51, 1991–2005 (2023).

Ranjan, P., Kaushal, A., Girdhar, A. & Kumar, R. Revolutionizing hyperspectral image classification for limited labeled data: unifying autoencoder-enhanced GANs with convolutional neural networks and zero-shot learning. Earth Sci. Inform. 18, 1–26 (2025).

Liu, Q., Xiao, L., Yang, J. & Wei, Z. Cnn-enhanced graph convolutional network with pixel- and superpixel-level feature fusion for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 59, 8657–8671 (2020).

Jia, H. et al. A convolutional neural network with pixel-wise sparse graph reasoning for COVID-19 lesion segmentation in CT images. Comput. Biol. Med. 155, 106698 (2023).

Avelar, P. H., Tavares, A. R., da Silveira, T. L., Jung, C. R. & Lamb, L. C. Superpixel image classification with graph attention networks. In Proc. 2020 33rd SIBGRAPI Conference on Graphics, Patterns and Images 203–209 (IEEE, 2020).

Bae, J.-H. et al. Superpixel image classification with graph convolutional neural networks based on learnable positional embedding. Appl. Sci. 12, 9176 (2022).

Ranjan, P. & Girdhar, A. Deep siamese network with handcrafted feature extraction for hyperspectral image classification. Multimed. Tools Appl. 83, 2501–2526 (2024).

Misra, D., Nalamada, T., Arasanipalai, A. U. & Hou, Q. Rotate to attend: convolutional triplet attention module. In Proc. IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision 3139–3148 (2021).

Deng, G. & Cahill, L. An adaptive Gaussian filter for noise reduction and edge detection. In Proc. 1993 IEEE Conference Record Nuclear Science Symposium and Medical Imaging Conference 1615–1619 (IEEE, 1993).

Kopparapu, S. K. & Satish, M. Identifying optimal Gaussian filter for Gaussian noise removal. In Proc. 2011 Third National Conference on Computer Vision, Pattern Recognition, Image Processing and Graphics 126–129 (IEEE, 2011).

Li, G., Muller, M., Thabet, A. & Ghanem, B. DeepGCNs: Can GCNs go as deep as CNNs? In Proc. IEEE/CVF International Conference On Computer Vision 9267–9276 (2019).

Xu, K., Hu, W., Leskovec, J. & Jegelka, S. How powerful are graph neural networks? arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.00826 (2018).

Hamilton, W., Ying, Z. & Leskovec, J. Inductive representation learning on large graphs. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Dynamic graph CNN for learning on point clouds. ACM Trans. Graph. 38, 1–12 (2019).

Loshchilov, I. et al. Fixing weight decay regularization in Adam. arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.05101 5 (2017).

Zhong, Z., Zheng, L., Kang, G., Li, S. & Yang, Y. Random erasing data augmentation. In Proc. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence Vol. 34, 13001–13008 (2020).

Loshchilov, I. & Hutter, F. SGDR: Stochastic Gradient Descent with Warm Restarts. In Proc. 5th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), (Toulon, France, 2017).

Van der Maaten, L. & Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 9 (2008).

Selvaraju, R. R. et al. Grad-CAM: visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proc. IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision 618–626 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work is partially supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (No.2023YFF0906504), by the National Natural Science Foundation of China through Project 62271393, and by the Open Project Program of the State Key Laboratory of Virtual Reality Technology and Systems, Beihang University (No. VRLAB2024C02).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xinda Liu: writing—review and editing, data collection. Jinkai Zhen: conceptualization, data collection, writing—original draft. Yangyang Liu: writing—review and editing, data collection. Guohua Geng: supervision, Writing—review and editing. Wuyang Shui: preparing the figures and the caption. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, X., Zhen, J., Liu, Y. et al. Multiple channel GCN with multiple directional Gaussian for porcelain microscopic image classification. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 254 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01716-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01716-9