Abstract

Clothing serves not only as a material entity but also as a crucial medium for cultural transmission and expression. The fashion design of the Renaissance period reflects the social trends and aesthetic pursuits of the time. However, traditional analytical methods are limited in efficiently extracting the cultural connotations embedded in these designs. This study develops a knowledge graph-based costume matching system that integrates cultural background, clothing knowledge, and expert commentary. The hierarchical recommendation model not only provides users with efficient and precise costume matching suggestions but also simplifies the selection process. The system constructs a knowledge graph through text mining and data annotation techniques, and optimizes matching recommendations using a weighting algorithm, ensuring cultural consistency and historical accuracy. Experimental results demonstrate that the system excels in recommendation accuracy, consistency, completeness, and immediacy. With its broad application potential and adaptability, the system is expected to contribute to cultural preservation, design fields.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The costume matching of the Renaissance period was influenced by various factors, including an individual’s identity, gender, occupation, social status, and lifestyle1, with adaptations made according to specific occasions and contexts. Beyond its aesthetic function, clothing of this era carried multiple layers of significance, serving to shape personal image, reflect the characteristics and cultural essence of the time, and construct symbols of cultural value2.

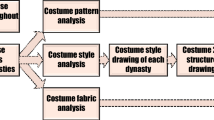

The diversity of influencing factors significantly increases the complexity of research on Renaissance clothing culture. Researchers in this field require not only extensive historical and cultural knowledge but also strong interpretive and integrative abilities3. For instance, during the design process, designers typically begin by examining the cultural background and clothing styles of the period. They then create costume designs that respect historical accuracy while aligning with the character’s image and contextual background4.

Renaissance attire is renowned for its distinctive structural sense and intricate design techniques. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the design approach breaks down the overall costume into multiple independent components, each meticulously crafted and then skillfully assembled to produce a cohesive visual effect5,6,7. This approach results in a layered decomposition and recombination in form. However, due to the diversity of design elements and the complexity of styles in Renaissance clothing, related documents and resources are highly fragmented and scattered. This fragmentation poses a significant challenge for the systematic organization and in-depth analysis of the clothing culture of this period. Traditional manual retrieval and information organization methods often fall short when addressing the complexity and rich cultural significance embedded in Renaissance fashion. They struggle to meet the stringent requirements for cultural consistency and historical accuracy in Renaissance costume matching, leading to potential confusion of styles across different historical periods and misinterpretations of cultural meanings.

Against this backdrop, a knowledge graph-based costume recommendation system can provide effective support for designers. Knowledge Graphs (KGs), an emerging method for organizing and managing digital resource knowledge, are increasingly applied across various fields, including recommendation systems8 such as news9, books10, music11, movies12, and product recommendations13. Introducing knowledge graphs into recommendation systems enriches semantic information, enhances interpretability, addresses the cold-start problem, and supports multi-hop reasoning and personalized recommendations. This significantly improves the accuracy, flexibility, and user experience of recommendations, assisting users in understanding and uncovering deeper insights14.

This study aims to assist researchers in rapidly accessing accurate costume information, simplifying the complex information retrieval process, and ensuring that costume matching aligns with specific cultural contexts and aesthetic standards by systematically presenting Renaissance clothing information, matching methods, cultural background, and their multidimensional connections. To achieve this goal, a knowledge graph-based costume recommendation system was developed. On one hand, the system efficiently filters costume recommendations based on selection criteria such as character identity, occasion, and gender, offering attire combinations that reflect specific cultural connotations while maintaining cultural consistency and historical accuracy. On the other hand, the recommendation system significantly enhances user efficiency in information retrieval, providing researchers with concise and accurate decision support. This allows them to quickly locate and apply appropriate costume matches, thereby offering intelligent support for fields such as film production, education, and cultural preservation.

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

First, this study achieves knowledge integration and structured presentation by proposing a multimodal knowledge graph construction framework tailored to the field of costume matching. This framework combines Renaissance clothing knowledge structures and expert recommendations, designing and constructing an ontology model that meets the study’s requirements, thereby laying the groundwork for the systematic presentation of cultural background and historical significance in costume design.

Second, an automated program was developed to dynamically import data into MySQL and Neo4j databases, resulting in a knowledge graph with 195 nodes and 2381 relationships. Based on this foundation, a recommendation algorithm using weight accumulation was designed and implemented, enabling real-time optimization of recommendations that dynamically adjust results according to user choices. Empirical experiments were conducted to validate the effectiveness of the recommendation system, and results demonstrated high accuracy and feasibility in practical applications.

Finally, a knowledge graph-based costume recommendation system was developed, providing an innovative case study for the digital display and cultural preservation of Renaissance attire. The system is highly transferable, allowing designers to apply it across diverse cultural and regional contexts by simply updating the data source, thus offering robust support for the protection and transmission of multicultural heritage.

Methods

This section introduces the development process of the knowledge graph-based recommendation system. As shown in Fig. 2, the framework consists of four main components: the data source layer, model layer, knowledge layer, and application layer.

Data source layer

To ensure data authenticity and expertise, the data sources for this study primarily include expert consultations, documented literature, and online data retrieval. Based on expert guidance, these sources are weighted according to their professional relevance, setting a foundation for the weight calculations in the subsequent recommendation algorithm.

Model layer

Building on the CIDOC CRM ontology, this layer incorporates expert commentary, Renaissance clothing characteristics, and fashion principles. By adding new categories, relationships, and metadata, we expand the ontology to construct a structure tailored to the study’s requirements.

Knowledge layer

The goal in this layer is to extract structured data from various text and image sources and transform it into knowledge. Key processes include knowledge extraction, knowledge fusion, and the identification of entities, relationships, and attributes from text. Images serve as one type of entity attribute, from which additional relationships and attributes can also be derived. The processed data is then imported into MySQL and Neo4j to create the knowledge graph.

Application layer

For practical application, we developed a web interface using Django and Vue, deploying it via Docker for containerization. The interface provides hierarchical options, associative selection, and information preview capabilities, facilitating an interactive and user-friendly experience.

Organization of data resource layer

In constructing the rule system for Renaissance costume matching, this study gathers fashion guidelines from multiple data sources, including documented literature, expert consultations, online data retrieval, and cinematic records. The primary data obtained consists of unstructured and semi-structured resources, including images and text.

To scientifically determine the weight assigned to each data source, this study references previous research that utilized subjective scoring experiments to quantify reliability15. We invited 10 experts in the history and theory of costume to assess the credibility and professionalism of these four data sources, using a weighted scoring method. The scoring scale was set from 1 to 10, where a higher score indicates greater credibility and professionalism for that source. To ensure scientific rigor and transparency in weight distribution, we employed a direct scoring and weighting approach, normalizing the total score for each data source so that the sum of all weights equals 1. The specific steps are as follows:

Constructing the scoring matrix

Construct the expert scoring matrix \(X={({x}_{{ij}})}_{m\times n}\), where \({x}_{{ij}}\) represents the score given by the \(i\)-th expert to the \(j\)-th data source, with \(i={\mathrm{1,2}},\ldots ,m\), and \(j={\mathrm{1,2}},\ldots ,n\). The structure of the scoring matrix is as shown in Eq. (1):

Calculate the total score for each data source

For each data source \(j\), calculate its total score \({S}_{j}\) based on the ratings provided by all experts, as described in Eq. (2):

Where \({S}_{j}\) represents the total score for the \(j\)-th data source.

Normalization of weight calculation

To ensure the sum of weights equals 1, divide the total score of each data source by the sum of the total scores for all sources. This yields the weight \({w}_{j}\) for the \(j\)-th data source, as shown in Eq. (3).

Here, \(\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{j=1}^{n}{w}_{j}=1\), fulfilling the requirement for weight normalization. The final detailed calculation results are presented in Table 1.

This approach to weight allocation not only lays the groundwork for the subsequent outfit recommendation algorithm but also ensures that the rule system for matching is established on a reliable and multidimensional basis. Additionally, it allows for flexible adjustments based on different data sources, thereby ensuring the scientific rigor and rationality of the final rules.

Organization of model layer

Ontology is a formal representation of concepts, entities, and their relationships, commonly used to structure knowledge within a specific domain. The purpose of ontology is to provide semantic associations and reasoning capabilities between data by defining explicit relationships and hierarchical classifications. It not only describes data but also builds complex semantic networks by defining relationships among entities.

Currently, there is no unified standard for ontology in the domain of digital resources for clothing16. However, systems such as VRA, CDWA17, and DC18 are widely adopted and can be readily adapted to traditional clothing digital resources. CDWA, established in 1990, was one of the first ontology standards applied in the art field. Having undergone numerous updates, it now includes approximately 540 elements19. CIDOC CRM is another widely-used ontology in the cultural heritage sector, employed for knowledge management in various scenarios20. The library at Beijing Institute of Fashion Technology used DC, CDWA, and VRA as reference standards to construct an ontology framework comprising 23 basic elements for costume images. This framework was subsequently expanded to 29 elements, divided into 14 core elements, 7 specialized core elements for costume images, and 8 individual elements, with certain elements enhanced by additional modifiers, including encoding system modifiers21. Wu developed an ontology for the textile patterns of Chinese She ethnic costumes, collecting information across foundational, explicit, implicit, and digitalized information categories. This ontology comprised 21 data elements, such as name, collection site, provider, creator, date, dimensions, location, and usage occasion22. These cases offer valuable references and exemplary frameworks for this study.

Existing ontology research does not yet fully or comprehensively capture the characteristics of Renaissance costumes, especially in terms of conveying their cultural significance and artistic value. This limitation hinders the ability to meet the needs of Renaissance cultural heritage preservation. Therefore, this study builds on the CIDOC CRM ontology structure, integrating unique Renaissance costume styles, cultural elements, and matching principles to construct a metadata standard and ontology structure tailored for this research. This model aims to assist researchers in systematically analyzing the historical background, cultural value, and design elements of Renaissance costumes with greater accuracy and efficiency, thus providing technological support for the preservation and transmission of Renaissance culture.

This study not only focuses on the aesthetic design of clothing but also emphasizes an in-depth exploration of its cultural significance and historical value. Ontology plays a crucial role in this research by providing a systematic framework that aids researchers in comprehensively understanding the relationships between historical context, cultural background, and design elements.

The ontology in this study draws upon and reuses core attributes from the CIDOC CRM ontology, such as period, style, and material. Simultaneously, it incorporates the unique characteristics and matching principles of Renaissance attire to develop a custom set of core categories. For instance, within the three essential elements of clothing, style and color have been refined to accommodate the design needs of various characters and occasions. Additionally, social context factors from the Renaissance period, such as class and occasion, are integrated as core elements to ensure that the attire not only aligns with the era’s characteristics but also conveys the social status and emotional expression of the character. The following sections will elaborate on the principles behind the establishment and design of the ontology, attributes, and relationships.

To meet the requirements of the subsequent recommendation functionality, this study first constructed a clothing element ontology based on the components of Renaissance attire. Then, focusing on the core factors influencing clothing choices, an element constraint ontology was developed to regulate clothing selections across different classes, occasions, and gender conditions. Finally, to ensure knowledge completeness and the system’s professional depth, additional related information ontologies were incorporated. This knowledge graph ontology model integrates multidimensional classifications and attribute settings, systematically presenting the structure, element compatibility, and cultural significance of Renaissance clothing. The categories and object properties of the knowledge graph model are shown in Table 2, with only the first two classification levels displayed due to space limitations.

In constructing the main clothing components for the recommendation system, this study categorizes items based on three core elements: style, material, and color. This ensures a clear classification structure within the recommendation system, allowing it to offer a diverse range of recommendation options. This classification framework not only enhances the accuracy of the recommendation system but also increases its flexibility, enabling it to better accommodate the diverse needs of users.

Style

Style is a core element of the recommendation system, referring to the overall form of the garment and its specific components. To achieve precise classification, this study subdivides style hierarchically based on the characteristics of Renaissance clothing. The first level of classification includes categories such as tops, bottoms, suits, components, and decorations, with further refinement in the second level; for instance, suits are divided into long dresses, robes, and similar items23,24. To provide a more systematic and detailed description of clothing entities, multiple attributes are incorporated within the style category. These include english_name and chinese_name, which reference and extend the E41_Appellation ontology from CIDOC CRM. Other attributes, such as Period, hey_day (peak period), and hey_period (peak era), draw from the structure of the E52_Time-Span subclass in E65_Creation. Additional attributes in the style category, such as origin, craft, description, detail, meaning, factor, and image_key, contribute a standardized structure and semantic support to the recommendation system, revealing the cultural significance and social symbolism behind the clothing, thus enhancing the intelligence and personalization of recommendations.

Material

As a vital component of clothing, material directly influences comfort, functionality, and symbolic meaning. In the Renaissance, material selection was not merely a matter of physical choice but also conveyed economic status and social identity. Accordingly, this study employs the E57_Material subclass within the E24_Physical_Human-Made_Thing category from CIDOC CRM for classification. To further describe the material’s physical attributes, the Feature attribute is incorporated to detail aspects such as texture and craftsmanship.

Color

Color held significant symbolic meaning in Renaissance clothing design, representing not only aesthetics but also social class, religious beliefs, and cultural symbols. In the recommendation system, the symbolic meaning and historical background of colors are prioritized. The color ontology encompasses classifications of hues and their symbolic implications. For instance, red was commonly associated with power, passion, and religious devotion during the period, and sumptuary laws restricted colors like purple and red to the nobility, while commoners often opted for modest shades such as brown or gray6. Therefore, understanding the use and symbolism of color is essential for grasping the cultural significance of Renaissance attire.

In the Renaissance, the key elements influencing clothing choices were defined as constraint elements to enable more precise matching within the recommendation process. These elements are further subdivided into occasion, class, and gender, forming the constraint ontology. This ensures that the recommendation system thoroughly considers user backgrounds and provides attire suggestions aligned with the cultural context.

Class

The social class ontology is primarily divided into noble class, middle class, peasant class, impoverished class, and enslaved class, with further subdivisions into specific categories. For example, the noble class is distinguished into hereditary nobility, high clergy (including bishops, cardinals, and the pope), urban nobility, and wealthy merchants. To deepen understanding, the Explanation attribute is added to provide social context. Renaissance attire strongly reflected social stratification: the noble class favored luxurious materials, intricate styles, and fine craftsmanship to display power and wealth25, while clothing for the lower classes leaned towards simplicity and practicality. Consequently, the recommendation system needs to account for the user’s social class background and suggest clothing styles that are appropriate to their status.

Occasion

Occasion is a critical dimension in the constraint ontology, as clothing choices varied significantly by occasion. The occasion ontology, based on Renaissance clothing customs, includes court occasions, religious ceremonies, social events, and daily activities7. For instance, formal occasions such as banquets or religious services required attire that conveyed decorum and formality, whereas daily or casual occasions emphasized comfort and ease. The recommendation system should therefore suggest clothing types that align with the user’s occasion needs, such as formal wear or casual wear, ensuring attire aligns with cultural standards of the event.

Gender

The gender ontology is divided into male, female, and unisex (attire suitable for both genders). Despite the unisex category, male and female clothing in the Renaissance had distinct design requirements and aesthetic preferences, necessitating separate consideration. The incorporation of gender elements further optimizes the recommendation system, enabling it to provide clothing choices that align closely with the user’s gender background.

In ontology construction, establishing complex semantic relationships between different concepts and entities is essential for machines to accurately understand, reason, and infer knowledge. The goal of this section is to build a comprehensive attribute-relationship model that establishes intricate semantic associations between concepts and entities. This model encompasses hierarchical relationships, namely classification relations within the same entity, as well as internal relationships within entities, reflecting the interdependencies between subjects, as shown in Table 3. These relationships define the interactions between concepts, instances, and attributes within the ontology. To achieve this, the modeling process is divided into two main steps: multi-level association modeling and internal entity relationship modeling, ensuring the logical rigor and semantic completeness of the ontology.

The previous section established a multidimensional data structure to reflect the key elements of the recommendation system. These dimensions form an integrated, multi-dimensional data view through their associations with the class category, as shown in Fig. 3, enabling users to conduct in-depth analysis from various perspectives.

In defining relationships between constraint ontologies, the focus is on the clothing’s association with the wearer’s class, occasion, and gender, which exhibit interdependent relationships. For instance, characters allowed to participate in court occasions are typically limited to the noble class, while attendance at religious ceremonies is mostly restricted to nobility and certain members of the middle class. This association ensures that the recommendation system can provide attire suggestions that align with the user’s status and occasion requirements.

Next, we establish the relationships influencing clothing choices:

First, class determines the style, material, and color of clothing. In the Renaissance, social stratification was distinctly expressed through clothing. For example, the upper nobility wore expensive silk, velvet, and satin, in luxurious colors like purple and gold, symbolizing power and status, often adorned with jewelry and intricate embroidery. In contrast, the middle class, although fashion-conscious, was restricted by economic limitations, opting for linen and wool with simpler designs but refined details. Thus, each clothing element directly reflected the wearer’s social class, serving as an important symbol of status.

Second, occasion plays a critical role in influencing clothing style and material. Renaissance attire varied according to the occasion; nobles wore formal and elaborate robes in religious ceremonies and court balls, with luxurious fabrics and rich adornments. In daily life, however, attire tended towards simplicity and practicality. For commoners, everyday clothing was modest and lightweight, suitable for their lifestyles and work demands26. Therefore, occasion greatly influenced clothing style, with different social etiquette and cultural norms impacting clothing choices.

Finally, gender differences had a significant impact on clothing style. During the Renaissance, men’s and women’s attire were distinct. Men typically wore fitted tops paired with wide trousers or robes, emphasizing strength and authority, while women wore corsets and wide skirts, designed to highlight elegance and modesty, with floor-length hemlines and longer sleeves to reflect social norms27. Given that gender ontology primarily influences clothing style, it functions as an attribute of the clothing category.

In dealing with ontologies across different domains, class structure enables the unified modeling of cross-domain concepts. This multi-layered association modeling approach provides semantic support for interoperability between different ontologies, laying a foundation for subsequent knowledge reasoning and query optimization.

Internal relationship modeling focuses on describing the subdivisions and associations within each ontology category, emphasizing the relationships among various levels within each ontology. This approach precisely models the attributes, instances, and interrelations within complex entities, allowing the ontology to exhibit top-down inheritance and intra-level associations across different layers, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

After subdividing the six primary categories—class, occasion, gender, clothing style, color, and material—the interrelated levels include secondary class, secondary occasion, tertiary style, secondary color, and secondary material. Gender acts as an attribute within the tertiary style category, directly filtering clothing options accordingly.

Organization of knowledge layer

Since Google first introduced the concept of Knowledge Graphs (KGs) in 2012, this technology has become a key component in artificial intelligence, finding broad applications in fields such as finance, healthcare, and intelligence analysis28,29. Knowledge graphs are typically divided into two main categories: general knowledge graphs and domain-specific knowledge graphs. Domain-specific knowledge graphs focus on particular industries, supporting knowledge organization and intelligent reasoning through in-depth data mining and refined modeling. Examples include the IMDB knowledge graph in the film industry30, the MusicBrainz knowledge base in the music domain31, and personalized fashion design knowledge graphs12. This study falls under the category of domain-specific knowledge graphs, focusing on integrating multifaceted information about Renaissance attire, social classes, and occasions for wearing particular outfits. By constructing a knowledge graph tailored to this field, the study aims to provide costume-matching recommendations, offering researchers a systematic reference to support the preservation and in-depth study of Renaissance fashion culture.

The construction of domain-specific knowledge graphs follows a top-down approach, beginning with insights from domain experts or existing knowledge systems to build a foundational ontology and knowledge framework, and subsequently filling in specific data and knowledge elements. For instance, the Freebase project extracted triples from Wikipedia and structured them into a knowledge graph through manual curation32. The specific construction process includes identifying the domain and user needs, designing the ontology framework, structuring data sources, and performing information extraction and knowledge fusion33. This process culminates in building a semantic network of entities and their relationships, with the selection of an appropriate graph database for storage and querying.

Multimodal Knowledge Graphs (MMKGs) integrate various forms of data, such as text, images, videos, and audio, providing richer and more multidimensional support for representation, understanding, and reasoning. Multimodal knowledge graphs are increasingly used in various aspects of the fashion industry, such as design resources, outfit matching, smart manufacturing, and personalized recommendation applications34. Examples include 3D fashion modeling knowledge graphs that incorporate 3D garment images and contour features35, A3-FKG, a fashion knowledge graph that integrates user preferences and attributes for item-specific insights36, and dynamic knowledge graphs for custom clothing production processes37. Clothing information acquisition mainly relies on visual image recognition to identify garment attributes or on methods like data scraping and information extraction38,39. Entity extraction uses manual methods and computational techniques, such as CNN-BNLSTM-CRF40 and Bi-LSTM+CRF41 algorithms.

The construction sequence in this study is as follows: first, a Renaissance clothing ontology framework is designed as a reference; next, unstructured and semi-structured data are converted to structured formats and filled in to correspond with metadata. Subsequently, this data is imported into MySQL and Neo4j databases via Python programs to construct a structured and standardized domain-specific multimodal knowledge graph.

This chapter, building upon the ontology framework discussed earlier, addresses the process of knowledge acquisition. It then details the transformation of unstructured and semi-structured data into structured data, followed by the mapping and population of metadata accordingly. Subsequently, Python scripts were developed to facilitate the dynamic import and representation of data from MySQL to Neo4j. This automation enhances operational efficiency, supports complex data preprocessing and transformation, and ensures reusability, maintainability, and scalability. The script also supports dynamic, real-time data synchronization, equipped with robust error handling and logging mechanisms.

Based on the ontology model framework constructed in the previous section, this section will proceed with information extraction and further implement knowledge fusion to enhance the knowledge structure of the system.

First, given that comprehensive and precise clothing elements and their characteristics play a critical role in improving the reliability of the knowledge graph35, this study employs a multi-channel approach involving manual identification and collection for information extraction. Core information related to Renaissance attire is extracted from various data sources. This process includes steps such as text processing, entity recognition, and attribute relationship extraction, ensuring the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the extracted information. Information extraction is systematically mapped according to the categories and attributes defined by the ontology model, ensuring that each piece of data is accurately aligned with the ontology categories of clothing style, material, color, class, occasion, and gender.

Knowledge fusion is achieved by aligning identical concept entities from different data sources and references, unifying them into standardized knowledge identifiers within the knowledge graph. This process effectively resolves issues of semantic ambiguity and data redundancy, thereby improving the consistency of knowledge relationships42. A key challenge in this process is multi-source heterogeneity, particularly due to variations in translation and language, which cause the same concept to have different names in different contexts. For instance, the upper garment “chemise” is referred to as “chemise,” “camicia,” and “camisa” in French, Italian, and Spanish respectively, while in English, the term retains the French-derived “chemise.” Such multi-source heterogeneity increases the complexity of entity alignment. Additionally, the ontology extraction results from literature are often sparse, necessitating supplementation through domain experts and online data, which in turn introduces more data heterogeneity issues. Some data sources may contain synonyms or polysemous terms, requiring similarity-based entity matching to improve selection accuracy and ensure the precision of knowledge fusion.

The database primarily stores two types of data: ontology information and clothing matching information. We performed preliminary preprocessing on the collected data, including data cleaning, field modification, filling in missing values, and recording timestamps. During the data import process into the MySQL database, we designed and created multidimensional data tables to reflect associations between different data elements. These multidimensional structures primarily combine through class indicators to construct an integrated data view. In this model, the occasion dimension, which mainly influences clothing style and material, is embedded within both the clothing style and material models. Gender, primarily affecting clothing style, is incorporated as an attribute within the clothing style model.

To further explore the relationships in clothing matching and support subsequent weight calculations, the imported data also includes a clothing matching information table. Each piece of matching information is categorized based on its source, with distinct weight values assigned to each category according to the four types of data sources previously mentioned. These weight values support the implementation of the subsequent recommendation algorithm. When documenting clothing matching information, this study determined limits on the number of items per outfit through extensive data analysis and expert feedback. Specifically, each outfit can contain a maximum of 3 tops, 3 bottoms, 1 suits, 8 components, and 3 decorations. The detailed matching data model is illustrated in Table 5.

Finally, a Python script was developed to handle data processing and import. The primary function of this script is to accurately import the collected main information and clothing matching data into the MySQL multidimensional database, ensuring efficient data storage, integration into the knowledge graph, and serving as a backend data source for the system.

During the process of importing MySQL data into Neo4j, ontology, entity data, relationships, and attributes correspond to labels, nodes, relationships, and properties within the knowledge graph, as shown in Fig. 5. The Python script utilizes Neo4j’s capabilities to sequentially create nodes for different categories, such as clothing style, color, material, and class, and establishes relationships between these nodes.

In constructing the knowledge graph, the script ensures the uniqueness of each node and creates clear hierarchical relationships for nodes across different levels. For instance, the classification information for clothing style is divided into multi-level nodes, connected by “subordinate relationships.” Similarly, the script establishes nodes and relationships for class, color, and material, forming a comprehensive and complex network structure.

Additionally, the script uses a predefined weighting model to assign different weights to relationships between nodes based on data sources, reflecting the importance of the information. Finally, all node and relationship information can be exported as a CSV file, facilitating subsequent data analysis and backup processes. This knowledge graph construction enables users to intuitively analyze the complex relationships in clothing matching and supports further recommendation research.

Organization of application layer

This chapter primarily discusses the system’s construction, which combines traditional and graph databases to store data and their relationships, using a front-end and back-end separated architecture to provide flexible user interaction and efficient data processing capabilities. This section will explore the system’s database design, key functional modules, and their implementation in detail.

In terms of application architecture, the front end is built using the Vue 3 framework, while the back end utilizes the Django framework. This architecture enhances the system’s maintainability and scalability.

Traditional recommendation systems based on collaborative filtering43 and content-based recommendations44 allow for a broader range of factors to be considered in making recommendation decisions45. With advancements in deep learning, models based on recurrent neural networks46, convolutional neural networks47, graph neural networks48, and attention mechanisms49 have become popular in recommendation algorithms.

In the fashion domain, clothing recommendation algorithms are mainly used to assess and weight garment attribute features and to conduct clustering analyses of these attributes. For instance, Hu et al.50 assign ratings to clothing based on user-assigned weights, recommending items with the highest ratings. Other researchers use clustering analyses of user preferences combined with the semantic features of clothing attributes to recommend suitable outfits, thereby enhancing recommendation accuracy51,52. Zhen40 employs a CNN-BNLSTM-CRF algorithm to recognize named entities in clothing, retrieve attribute information, and recommend items through a collaborative filtering system.

In recommendation algorithms that integrate knowledge graphs, Zhu et al.53 improved entity recognition efficiency by automatically identifying fundamental attributes, such as style and color, in online reviews to build a fashion knowledge graph. Wen et al.54 proposed combining a fashion recommendation system with semantic knowledge from a fashion knowledge graph and user context-specific needs to alleviate the cold-start problem and enhance recommendation quality. They used the Apriori algorithm to capture relationships between garment and environmental attributes, recommending the most suitable clothing based on user requirements. Cai Liling et al.55 highlighted the significant influence of online review content on consumer purchase intentions, suggesting the inclusion of auxiliary information to enrich clothing attributes in recommendation systems. Additionally, Yu56 developed a knowledge graph-based recommendation system that provides personalized recommendations by incorporating weather conditions and considering user-system interactivity.

The recommendation needs in this study are complex, requiring historically accurate costume matching along with detailed knowledge presentation. Therefore, this study proposes a knowledge graph-based weighted accumulation recommendation algorithm to ensure rigor in historical style and cultural consistency, while also effectively supporting in-depth cultural information display. This approach enables precise communication and broad dissemination of Renaissance clothing culture. In this chapter, the development steps of the recommendation algorithm and system will be presented in detail.

As previously noted, the matching data is divided into four groups based on data sources: literature records, expert consultations, online data retrieval, and film records. Each group is assigned a different weight according to its source. Each matching data entry contains nine dimensions: three tops, three bottoms, one suit, components, and decorations. The order of these dimensions aligns with the steps users follow in the matching process. The first dimension (top) is required, while the others are optional. Components can include up to 8 items, and decorations up to 3.

The algorithm for data processing proceeds as follows: first, all matching data is grouped by source, and the weight is calculated for each group. Then, each matching entry within each group is iterated over, with each pair of dimension values being associated to generate a series of element combinations. If both elements in a combination are non-empty, the relationship between these two elements is strengthened by adding the weight of the respective source group, representing an increase in the weight between the two nodes in the knowledge graph. For combinations that appear repeatedly, the weight is accumulated, with the total being the sum of occurrences of that combination, as indicated by the formula.

Let \(G\) represent a knowledge graph, where \(V\) denotes the set of nodes and \(E\) the set of edges, representing relationships between nodes. The accompanying dataset, \(D\), consists of multiple dimensions \({d}_{1}\), \({d}_{2}\), \({d}_{3}\),…,\({d}_{9}\) for each data entry. The data originates from source \(S\), with each source assigned a weight \({w}(S)\), specified as follows:

\({\rm{Literature}}\; {\rm{Documentation}}\!\!:\,w\left({S}_{1}\right)=0.373\)

\({\rm{Expert}}\; {\rm{Consultation}}\!\!:\,w\left({S}_{2}\right)=0.298\)

\({\rm{Online}}\; {\rm{Data}}\; {\rm{Retrieval}}\!\!:\,w\left({S}_{3}\right)=0.227\)

\({\rm{Film}}\; {\rm{and}}\; {\rm{Television}}\; {\rm{Records}}\!\!:\,w\left({S}_{4}\right)=0.102\)

For each data entry \({d}\in D\), where each dimension is denoted by \({d}_{i}\), we define the edge weight \({W}({d}_{i},{d}_{j})\) for any two non-empty dimension values \({d}_{i}\) and \({d}_{j}\) as formulated in Eq. (4):

Where \(W({d}_{i},{d}_{j})\) represents the cumulative weight between the current pair of nodes \({d}_{i}\) and \({d}_{j}\), and \(w(S)\) is the weight value associated with the data source. For each repeated pair \({d}_{i}\), \({d}_{j}\), the weight value accumulates according to the following formula, as shown in Eq. (5):

Where \(n\) denotes the frequency of this pair in the dataset.

Finally, for any pair of nodes in the graph that lack an association, the weight value is set to 0, as shown in Eq. (6):

After calculating the weights for all combinations, each unique pair and its corresponding cumulative weight are used to update the relationships between nodes in the knowledge graph using Cypher query statements. The weight attribute of each relationship is set to the calculated weight value. Finally, for any relationships lacking a weight attribute, the attribute is uniformly updated to 0 to ensure that the weight attribute of all node relationships in the knowledge graph is properly assigned.

This approach establishes complex relationships between nodes from multidimensional, multi-source fashion matching data, providing foundational data support for intelligent fashion matching recommendations.

The clothing recommendation feature in this section is based on the user’s initial selection criteria, combined with inherent attribute information of clothing items in the knowledge graph and pre-defined matching combinations among garments. The overall process is illustrated in Fig. 6.

The approach begins with the user selecting required parameters on the page, including class, occasion, material, color, and gender. These parameters are then passed to the backend interface. Upon receiving the parameters, the backend queries the database for all top-wear items that meet the specified criteria, returning them to the frontend as selectable options for the next component in the selection sequence. The chosen gender serves as a filtering criterion for all subsequent clothing recommendations.

The user then selects the first top item on the page, which is mandatory. This selection is sent to the backend, which queries the knowledge graph to retrieve other compatible top items related to the selected item, using Cypher queries in Neo4j to locate matching nodes and relationships. Once matching top items are identified, they are sorted by the weight attribute of their matching relationships, and the sorted list is sent back to the frontend as options, arranged in descending order of recommendation value.

The clothing selection process involves nine steps in total, following the sequence of Top > Top > Top > Bottom > Bottom > Bottom > Outfit > Components > Decoration. Apart from the first step, the user can choose to select items or leave fields blank as desired. After completing all selection steps, the user can view a table of all selected items on the interface, containing detailed attribute information for each clothing item.

Results

Data collection

The data is primarily sourced from literature documentation, expert consultation, online data retrieval, and film and television records. Detailed sources are listed in the Supplementary. Literature, expert input, and online searches mainly focus on collecting clothing elements and styling information, covering aspects such as materials, styles, colors, historical context, and cultural significance. The results of collecting detailed information on clothing elements are shown in Table 4, which provides an example of single-item information collection, listing specific attributes and classifications.

Film records focus on collecting information about clothing and styling, particularly on how these elements are applied across various occasion and characters. By analyzing costume choices in films, researchers can identify trends, design styles, and the emotions or social status conveyed by characters. Figure 7 illustrates extracted examples of clothing matches from Elizabeth: The Golden Age.

Database presentation

As the relational database for this study, MySQL primarily stores raw data. The table structure is designed in accordance with standard relational database normalization principles to ensure data consistency, integrity, and feasibility for subsequent operations. A sample view of the imported data in MySQL is provided in Fig. 8.

After importing the data from MySQL into Neo4j, all node and relationship data were exported in CSV format to facilitate backup, migration, data auditing, and failure recovery. This export includes a total of 195 node entries and 2381 relationship entries. A sample of this data is shown in Fig. 9.

Knowledge graph visualization

In the knowledge graph, nodes represent entities such as style, color, material, and class, with each node containing detailed attribute information, including clothing classification, origin, description, and period of popularity. The edges in the graph depict relationships between nodes. For instance, the main clothing node and the component node are connected through a “Match_to” relationship, indicating that they can appear as coordinated items, as shown in Fig. 10.

In the visualization process, Neo4j’s query language, Cypher, can be used to generate visual representations of various nodes and relationships. For example, this section can showcase the hierarchical structure of clothing classifications, including primary, secondary, and tertiary levels, along with their hierarchical relationships. Additionally, it is possible to display connections between different entities, such as the matching relationships between color and class or the pairing relationships between different styles.

Recommendation system presentation

The user interface (UI) was developed using the Element Plus framework, which offers a comprehensive set of UI components to meet common application needs, including forms, buttons, navigation, and data displays. This framework enables a consistent look and feel across interface styles and interactive effects, facilitating the rapid construction of a fully functional UI while minimizing the need for development from scratch.

The UI components used in this development include the cascader panel selector (el-cascader-panel), image component (el-image), dropdown selector (el-select), table component (el-table), step indicator component (el-step), and button component (el-button). The cascader panel selector was chosen for setting preconditions, as it allows for multi-dimensional data selection and effectively displays the interrelationships between each dimension, as illustrated in Fig. 11.

After completing the precondition selection, users click “Next” to proceed to the first-level tops selection. The first-level tops interface utilizes a radio panel component, with each option displaying the clothing item’s Chinese name and a corresponding image. Clicking on an image allows users to preview multiple images of that garment. The subsequent interfaces for selecting tops, bottoms, suits, and components follow a similar logic, but the available options are filtered based on prior selections to quickly return multiple matching suggestions, sorted by weight. For components and decorations, a dropdown selection component is used. The maximum selection limit for components is set to 8, while for decorations it is set to 3. Once the maximum number is reached, the remaining options become unclickable, as shown in Fig. 12.

After completing all selection steps, clicking “Finish” displays all selected clothing information in a table component. This table provides an overview of each chosen item, including details such as source, period, classification, craftsmanship, and other relevant fields, offering a comprehensive summary of the selected attire.

Quality evaluation

In this study, we developed a knowledge graph-based costume matching system focused on the Renaissance period. Given that the system aims to provide specialized matching recommendations for content with high historical and artistic value, the professional requirements for the recommendation system are exceptionally stringent. To ensure the quality of recommendations and meet domain-specific needs, several experts in Renaissance culture and fashion design were invited to conduct a comprehensive quality evaluation of the system. This evaluation focused on four dimensions: accuracy, consistency, completeness, and immediacy.

Accuracy

The core of the recommendation system lies in providing pairing suggestions based on historical accuracy, so accuracy is an important metric for evaluating the system’s quality. The expert evaluation team reviewed the system’s style recommendations, attribute information display, and historical authenticity to ensure that the recommended content aligns with the style, dress norms, and scene reproduction of the Renaissance period. To assess the accuracy of the recommendation system, 60 tests were conducted, and based on the expert evaluation results, the following confusion matrix was constructed:

True Positive (TP): Correct recommendations made by the system, correctly judged by experts = 51

False Positive (FP): Incorrect recommendations made by the system, incorrectly judged as correct by experts = 3

False Negative (FN): Correct recommendations made by the system, incorrectly judged as incorrect by experts = 2

True Negative (TN): Incorrect recommendations made by the system, correctly judged as incorrect by experts = 4

Accuracy refers to the proportion of correct recommendations in the system. Using the data as shown in equation (7):

Precision refers to the proportion of actual correct recommendations among those the system identified as correct. Using the data as shown in Eq. (8):

Recall refers to the proportion of actual correct recommendations that the system correctly identifies. Using the data as shown in Eq. (9):

F1 score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall. Using the data as shown in Eq. (10):

The evaluation results show that the system’s recommended pairings, based on historical background, present a high level of accuracy in reflecting Renaissance elements.

Consistency

The consistency evaluation examines whether the recommendation system can provide consistent recommendations without conflicts in knowledge expression. For example, when recommending tops, a higher-weighted combination, such as the Kecken-Daubrit-Sumiz combination, will always appear in the subsequent recommended list, regardless of the first item selected, as long as the preceding choices remain unchanged. In the consistency test, we conducted 50 experiments on three recommendation systems (Knowledge Graph-based recommendation system, Collaborative Filtering-based recommendation system, and Content-based recommendation system) to evaluate their consistency in recommendation frequency and user selection distribution under the same conditions. The experimental results show that the Knowledge Graph-based recommendation system demonstrates a significant advantage in terms of consistency.

The experiment measured the frequency of the “highest weight combination” in each recommendation and the proportion of users selecting clothing that fits the Renaissance style. The specific data is as Table 5.

The Knowledge Graph-based recommendation system shows a significant advantage in consistency testing. Both its recommendation frequency and user selection distribution demonstrate high consistency and stability, allowing for a more precise capture of the cultural connotations of Renaissance-era clothing. In contrast, the Collaborative Filtering and Content-based recommendation systems perform weaker in terms of consistency, with their recommendations more likely to be influenced by user history preferences or item features, thus affecting the stability and accuracy of the recommendations.

Completeness

Completeness in recommendations refers to whether the system includes essential elements and details from the Renaissance period. For this, the evaluation team meticulously examined the generated recommendations to ensure that the content encompassed clothing styles, colors, materials, social class, occasion, and gender, as well as detailed attributes of each entity. The system performed excellently in the integrity evaluation, demonstrating a high level of completeness. It is able to provide users with comprehensive and precise clothing matching suggestions, showcasing the cultural connotations of Renaissance-era attire.

Immediacy

Finally, the immediacy assessment evaluated the system’s adaptability to new information or updated requirements. During system construction, all backend data was imported into the database via Python scripts, enabling high flexibility and efficient data updates. The script supports convenient dynamic updates, allowing for one-click system-wide updates with simple additions or modifications to the data source. This design enhances the system’s real-time responsiveness and adaptability, enabling it to promptly incorporate new Renaissance-related information, thus better serving users’ needs for timely recommendations.

Discussion

This study successfully developed a Knowledge Graph-based clothing matching system for the Renaissance period. As an important cultural carrier, clothing embodies the historical traces of economic, political, and social changes throughout different periods. This system integrates Renaissance-era clothing information from multiple dimensions, including styles, colors, fabrics, social classes, occasions, and gender, ensuring high standards in accuracy, consistency, completeness, and timeliness. It not only provides users with professional and precise clothing matching suggestions but also reveals the cultural connotations behind the clothing. The system demonstrates significant application value and expansion potential, such as further expansion into fashion design (e.g., film creation, clothing design) and education fields (e.g., museum displays, children’s education). However, despite the promising application of Knowledge Graphs in cultural and historical fields demonstrated by this research, there are still several limitations that require further exploration and improvement.

Firstly, the current system mainly focuses on matching clothing and accessories, but it has not fully considered individual user characteristics, such as age differences and other factors that may influence matching choices. Renaissance clothing is not only closely related to social class but may also differ based on individual factors like age and personality. Therefore, future research could expand the system by incorporating more personalized dimensions to enhance the personalization and precision of the recommendations.

Secondly, the system design has not fully considered the evolution and differences in clothing elements across different historical periods or cultural backgrounds. For example, there are certain differences in clothing styles during the Renaissance depending on the region or period. The current system has not fully addressed these subtle historical and cultural differences. Therefore, future research could incorporate cross-period and cross-cultural clothing matching elements into the recommendation system to improve its professionalism and cultural adaptability. Particularly when integrating historical figures, art movements, or specific historical events, the system could offer recommendations with greater cultural depth, enhancing the user’s historical experience and cultural understanding.

In conclusion, although this study demonstrates the powerful potential of a Knowledge Graph-based clothing recommendation system, there are still many aspects that need further improvement. Future research can enhance the system’s personalization and cross-cultural adaptability, refine the content of the knowledge graph, and further improve the recommendation system’s professionalism and application value to meet the multi-layered needs of cultural heritage preservation and promotion.

Data availability

The datasets and code used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The code used and/or developed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kuper, H. Costume and identity. Comp. Stud. Soc. Hist. 15, 348–367 (1973).

Laverty, C. Fashion in Film (Laurence King Publishing, 2021) https://www.google.com/books?hl=zh-CN&lr=&id=h_9wEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT13&dq=Laverty+C.+Fashion+in+Film&ots=p4mt5f0hqV&sig=sSCPNW1vyqQuiYFoPR7dLnN8vMo.

Yin, F. Analysis of the Role of Costume Design in Shaping the Characters of Film and Television. Front. Art Res. 5, https://francis-press.com/uploads/papers/eZPqF8qZcjEAQub5pqcziY6LTYnpCdeWW22xcHQK.pdf (2023).

Landis, D. N. Filmcraft: Costume Design (Ilex Press, 2012), https://www.google.com/books?hl=zh-CN&lr=&id=3yCkCgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT9&dq=fashion+film+costume+design&ots=dGlxjurVu6&sig=IUlTeN1g2CBlLq0OcyJxuJXI0Pw.

Rublack, U. Clothing and cultural exchange in Renaissance Germany. Cultural Exch. Early Mod. Eur. 4, 258–288 (2007).

McCall, T. Materials for Renaissance fashion. Renaiss. Q. 70, 1449–1464 (2017).

Bridgeman, J. Dressing Renaissance Florence: Families, Fortunes and Fine Clothing. Engl. Historical Rev. 119, 779–781 (2004).

Khan, N., Ma, Z., Ullah, A. & Polat, K. Categorization of knowledge graph based recommendation methods and benchmark datasets from the perspectives of application scenarios: A comprehensive survey. Expert Syst. Appl. 206, 117737 (2022).

Wang, H., et al. RippleNet: Propagating User Preferences on the Knowledge Graph for Recommender Systems. In: Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, 417–426, (ACM, 2018). https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3269206.3271739.

Zhang, F., Yuan, N. J., Lian, D., Xie, X., Ma, W. Y. Collaborative Knowledge Base Embedding for Recommender Systems. In: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 353–362 (ACM, 2016), https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2939672.2939673.

Huang, J., Zhao, W. X., Dou, H., Wen, J. R. & Chang, E. Y. Improving Sequential Recommendation with Knowledge-Enhanced Memory Networks. In: The 41st International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research & Development in Information Retrieval, 505–514 (ACM, 2018), https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3209978.3210017.

Wang, H., et al. Knowledge-aware Graph Neural Networks with Label Smoothness Regularization for Recommender Systems. In: Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 968–977 (ACM, 2019), https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3292500.3330836.

Wang, X., Zhang, Y., Wang, X. & Chen, J. A Knowledge Graph Enhanced Topic Modeling Approach for Herb Recommendation. In: Li, G., Yang, J., Gama, J., Natwichai, J., Tong, Y., editors. Database Systems for Advanced Applications. Cham: Springer International Publishing; p. 709–724. (Lecture Notes in Computer Science; 11446). https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-18576-3_42 (2019).

Zhang, J. C., Zain, A. M., Zhou, K. Q., Chen, X. & Zhang, R. M. A review of recommender systems based on knowledge graph embedding. Expert Syst. Appl. 250, 123876 (2024).

Wang, T. C. & Lee, H. D. Developing a fuzzy TOPSIS approach based on subjective weights and objective weights. Expert Syst. Appl. 36, 8980–8985 (2009).

Ye, Q. Metadata construction scheme of a traditional clothing digital collection. Electron. Libr. 41, 367–386 (2023).

Liang, J., Wang, Q. & Zhao, Y. Metadata construction for the digitalization of traditional costumes of indigenous ethnic groups in Guangxi. J. Guangxi Univ. Nationalities 43, 112–116 (2021).

Zhou, W. & Zhao, H. Y. Metadata construction for the digitalization of traditional ethnic costumes. J. Graph. 39, 9 (2018).

Baca, M. & Harpring, P. Categories for the description of works of art, https://apo.org.au/node/14985 (2017).

Lu, L. et al. A study on the construction of knowledge graph of Yunjin video resources under productive conservation. Herit. Sci. 11, 83 (2023).

Li, Y. Core elements of clothing image metadata. Digital Library Forum 6, https://doi.org/10.3772/j.issn.1673-2286.2014.01.008 (2014).

Wu, Y. J. Design and application of the pattern factor library for She ethnic costumes (Zhejiang Sci-Tech University, 2022).

Jacob, P. L. Manners, Customs, and Dress During the Middle Ages, and During the Renaissance Period. (Chapman and Hall, 1874).

Pleydell, B. H. The Spanish Tudors: Fashioning the Anglo-Spanish Elite through Dress, c. 1554–1603, and beyond. PhD diss, University of Bristol, https://research-information.bris.ac.uk/files/188686962/Final_Copy_2019_01_23_Pleydell_H_PhD_Redacted.pdf (2018).

Currie, E. Clothing and a Florentine style, 1550–1620. Renaiss. Stud. 23, 33–52 (2009).

Cunnington, C. W. & Cunnington, P. The history of underclothes. Courier Corporation, https://www.google.com/books?hl=zh-CN&lr=&id=36FPs4p8tjEC&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=The+History+of+Underclothes&ots=v5GZG10iFC&sig=df3EOglZ5hBMTK_96cmifmQJDT4 (1992).

Richardson, C. Clothing Culture, 1350-1650. Routledge, https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9781315260068/clothing-culture-1350-1650-catherine-richardson (2017).

Shen, T., Zhang, F. & Cheng, J. A comprehensive overview of knowledge graph completion. Knowl. Based Syst. 255, 109597 (2022).

Du, Z. Q., Li, Y., Zhang, Y. T., Tan, Y. Q. & Zhao, W. H. Research on construction methods for knowledge graphs in natural disaster emergency response. J. Wuhan. Univ. 45, 1344–1355 (2020).

Chen, K. T. & Luo, J. When Fashion Meets Big Data: Discriminative Mining of Best Selling Clothing Features. In: Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web Companion - WWW’17 Companion, 15–22 (ACM Press, 2017), http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=3041021.3054141.

Lo, L. et al. Dressing for attention: Outfit-based fashion popularity prediction. In: 2019 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), 3222–3226 (IEEE, 2019).

Bollacker, K., Cook, R. & Tufts, P. Freebase: A shared database of structured general human knowledge. In: AAAI, 1962–1963, https://cdn.aaai.org/AAAI/2007/AAAI07-355.pdf (2007).

Ji, S., Pan, S., Cambria, E. & Marttinen, P. Philip SY. A survey on knowledge graphs: Representation, acquisition, and applications. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 33, 494–514 (2021).

Gong, Q. Y. & Li, X. H. Research progress of knowledge graphs in the field of clothing. Silk 60, 8–14 (2023).

Zheng, J. & Hong, W. Construction of Knowledge Graph of 3D Clothing Design Resources Based on Multimodal Clustering Network. Computational Intell. Neurosci. 1–12, https://www.hindawi.com/journals/cin/2022/1168012/ (2022).

Zhan, H. et al. A^3-FKG: Attentive Attribute-Aware Fashion Knowledge Graph for Outfit Preference Prediction. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 24, 819–831 (2021).

Shen, X., Li, X., Zhou, B., Jiang, Y. & Bao, J. Dynamic knowledge modeling and fusion method for custom apparel production process based on knowledge graph. Adv. Eng. Inform. 55, 101880 (2023).

Yang, Z., Su, Z., Yang, Y. & Lin, G. From recommendation to generation: A novel fashion clothing advising framework. In: 2018 7th International Conference on Digital Home (ICDH), 180–186 (IEEE, 2018).

Deng, Q., Wang, R., Gong, Z., Zheng, G. & Su, Z. Research and implementation of personalized clothing recommendation algorithm. In: 2018 7th International Conference on Digital Home (ICDH), 219–223 (IEEE, 2018).

Zhen, D. S. Application research on recommendation technology based on knowledge graphs in the field of clothing (Donghua University; 2021).

Cui, L. Construction and application of knowledge graphs for ethnic minority costume culture (Yunnan Normal University, 2021).

Holzinger, A., Malle, B., Saranti, A. & Pfeifer, B. Towards multi-modal causability with graph neural networks enabling information fusion for explainable AI. Inf. Fusion 71, 28–37 (2021).

Chen, R. et al. A survey of collaborative filtering-based recommender systems: From traditional methods to hybrid methods based on social networks. IEEE Access 6, 64301–64320 (2018).

Pazzani, M. J. & Billsus, D. Content-Based Recommendation Systems. In: The Adaptive Web, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 4321 (eds, Brusilovsky, P., Kobsa, A., Nejdl, W.) 325–341 (Springer, 2007). http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-540-72079-9_10.

Zhang, Y., Yuan, J., Wei, C. & Xie, Y. Aggregating knowledge and collaborative information for sequential recommendation. IDA 28, 279–298 (2024).

Hidasi, B., Karatzoglou, A., Baltrunas, L. & Tikk, D. Session-based Recommendations with Recurrent Neural Networks. arXiv, http://arxiv.org/abs/1511.06939 (2016).

Tang, J. & Wang, K. Personalized Top-N Sequential Recommendation via Convolutional Sequence Embedding. In: Proceedings of the Eleventh ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, 565–573, (ACM, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1145/3159652.3159656.

Chang, J. et al. Sequential Recommendation with Graph Neural Networks. In: Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 378–387 (ACM, 2021).

Kang, W. C. & McAuley, J. Self-attentive sequential recommendation. In: 2018 IEEE international conference on data mining (ICDM), 197–206 (IEEE, 2018). https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/8594844/.

Hu, J. L., Wang, Z. F. & Han, S. G. Research on personalized clothing recommendation model based on user preferences. J. Zhejiang Sci. Tech. Univ. 40, 136–143 (2018).

Wang, Y. & Ma, S. C. Design and application of personalized recommendation system based on user behavior. Comput. Syst. Appl. 19, 29–33 (2010).

Ai, L. Research on personalized clothing recommendation based on product attributes and user clustering. Mod. Inf. 35, 165–170 (2015).

Zhu, M. & Zhen, D. S. Chinese Named Entity Recognition for Clothing Knowledge Graph Construction. In: IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 012043 (IOP Publishing, 2019). https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1757-899X/646/1/012043/meta.

Wen, Y., Liu, X. & Xu, B. Personalized clothing recommendation based on knowledge graph. In: 2018 International Conference on Audio, Language and Image Processing (ICALIP), 1–5 (IEEE, 2018), https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/8455311/.

Cai, L. L., Ji, X. F. & Pang, C. Factors influencing the usefulness of online clothing reviews. J. Text. Res. 39, 158–163 (2018).

Yu, Y. Y. Research and application of knowledge graph in the field of clothing and apparel (Wuhan Textile University, 2023).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by data provided by the Shanghai Dongyi Art Museum and Donghua University. We are deeply grateful to the ten experts in fashion history for their invaluable assistance with semantic annotations and data validation. Our sincere thanks also go to the anonymous reviewers, whose suggestions greatly enhanced the quality of this research. Additionally, the authors acknowledge the financial support from the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant NO. 2232024G-08).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Y.T.: Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Data curation; Y.X.F.: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition; W.J.P.: Validation, Supervision, H.M.R.: Resources, Investigation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xia, Y., Yao, X., Wang, J. et al. Leveraging knowledge graphs for renaissance costume matching and cultural transmission. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 219 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01742-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01742-7