Abstract

In the era of global social and economic changes, World Natural Heritage Sites (WNHS) face growing threats, especially Karst WNHS with their distinct landform, ecosystems, and geology. Assessing the threat intensity of global karst WNHS is crucial for protecting their Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) and improving management. This study used the Threat Intensity Coefficient (TIC) to analyze spatio-temporal threat factors for karst WNHS. Results showed there were 31 karst WNHS globally, unevenly distributed, mostly meeting criteria (vii) and (viii). Thirteen factors impact them, with nine human-related. The threat intensity of karst WNHS is rising, particularly in Asia & Pacific (APA), while it is well-controlled in Europe and North America (EUR). Management and institutional factors (F9) pose the highest threat, followed by social/cultural uses of Heritage (F7) and buildings and development (F1). By integrating threat levels with States of Conservation reports, high-threat factors were identified in EUR and APA, highlighting the need for conservation. This research offers valuable insights for protecting global karst heritage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the characteristics of outstanding features, uniqueness and diversity of global significance, World Heritage Sites (WHS) are becoming increasingly a source of national pride and a collection of world - famous landmarks1,2 and it is a non-renewable and precious resource with Outstanding Universal Value (OUV)3. Only with this value can it be inscribed on the World Heritage List (List)4. OUV is the core concept of the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (Convention). Only when this value is possessed can it be recognized by the Convention5. OUV consists of three main elements: (1) WHS meet at least one of the evaluation criteria; (2) WHS meet the conditions of integrity and/or authenticity; and (3) WHS meet the requirements for protection and management. Among them, there are ten WHS criteria. Criteria (i) to (vi) are applicable for the World Cultural Heritage and Criteria (vii) to (x) are for the World Natural Heritage (Table 1). As of the end of 2024, 1223 WHS have been inscribed on the List, including 952 Cultural Heritages, 231 Natural Heritages, and 40 Mixed Heritages, distributed in a total of 168 States Parties6.

Since the adoption of the Convention in 1972, the number of WHS has been increasing annually, but the imbalance between the growing human population and their natural and cultural environments has caused numerous threats to WHS7. The Convention notes that the Cultural Heritage and the Natural Heritage are increasingly threatened with destruction. World Heritage is vulnerable to natural or human-induced events that threaten its integrity and undermine OUV. The 44th session of the World Heritage Committee (WHC-Committee) emphasized the need to address the challenges WHS faces8. With a mission to encourage States Parties to establish protection, conservation, and presentation services and to take appropriate measures for the protection of WHS, World Heritage Center (WHC) carries out Reactive Monitoring (RM) on the protection and management of WHS. RM is defined in The Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention (Operational Guidelines) as being “the reporting by the WHC, other sectors of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the Advisory Bodies to the WHC-Committee on the state of conservation of specific WHS that are under threat”9. According to Article eleven, Paragraph four of the Convention, WHC-Committee may at any time, in case of urgent need, make a new entry in the List of WHS in Danger and publicize such entry immediately. According to the statistics on the official website of the WHC as of the end of 2024, a total of 56 WHS have been inscribed on the List of WHS in Danger, of which 15 are Natural Heritages and 41 are Cultural Heritages, and even three WHS have been delisted by the WHC due to serious damage to the OUV6.

Threat Intensity Coefficient (TIC) was established by the WHC in 2007 as a statistical measure of the extent to which factors affecting WHS are detrimental to the OUV of any Heritage Site. A systematic and standardized quantitative analysis of the State of Conservation (SOC) reports submitted by WHS is carried out, based on threat factors and in terms of space and time. The severity of threats to WHS can be assessed more intuitively and accurately, and targeted advice can be provided on the conservation and management of WHS.

Karst landscapes are widely distributed on the Earth’s surface, covering about 15% of the land area10,11. The karst landform is unique in both its surface and subsurface double layer structure12,13,14. Many karst-related WHS have been inscribed on the List based on their remarkable ecological and geological structures as well as other outstanding values. However, soil loss can easily lead to rocky desertification15,16,17. In addition, ineffective land use will result in vegetation degradation and ultimately lead to rocky desertification18,19,20. Rocky desertification not only affects the OUV of karst World Natural Heritage Sites (WNHS), but also seriously restricts economic and social development and threatens human living space12,21. Therefore, we need to explore the threat factors affecting karst WNHS and threat intensity so as to provide a scientific basis for the karst WNHS to formulate targeted protection strategies and measures, which will help to better protect and pass on these precious sites.

Currently, there is a dearth of research on threats to global karst WNHS. In this paper, a literature search was conducted based on the core databases of China Knowledge Network and Web of Science. The search time range is the maximum time range of the database, and the search time is up to January 1, 2024. Using “Subject” as the search term, “World Natural Heritage” is the first search term, and “Karst” is the second search term. The results showed that there were 352 records matching the search terms. Among them, there were 204 papers in Chinese and 48 papers in English. Taking “Threat” as the keyword for the third search, a total of 19 documents were searched, with 11 in Chinese and eight in English, and most of the related documents were focused on localized studies22,23,24,25,26,27 or single factors affecting the study28,29,30,31. Every three years, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) publishes a World Heritage Conservation Outlook assessing the conservation prospects of all WNHS32, but does not specifically analyze karst WNHS. However, this shows that there is a lack of research on threats to karst WNHS on a global scale.

In the context of global social and economic changes, threats to global WNHS are increasing. Almost all types of threats are occurring in an increasing number of WNHS28. Against this backdrop, this paper is based on the official data released by UNESCO, WHC, and IUCN and takes global karst WNHS as the research object to assess the threat intensity of global karst WNHS. The temporal and spatial changes in the factors affecting karst WNHS were researched and TIC was used to quantify the threat intensity. The findings may provide a scientific basis for decision-making and promote sustainable development.

Methods

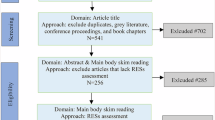

The dataset analyzed in this study was compiled from official publications by UNESCO, WHC, and IUCN, following the TIC calculation framework described in the Third paragraph of the introduction. To ensure temporal precision, all records were standardized to annual increments, with the dataset covering the period up to December 31, 2023. Following are the statistics on the number and distribution of karst WNHS and karst World Mixed Heritage Sites (collectively known as WNHS) on the List. The number of SOC reports and the affecting factors are counted. TIC proposed by the WHC is applied, and the UNESCO regional division standards are adopted to count the threat intensities of karst WNHS in the world as Asia & Pacific (APA), Europe and North America (EUR), Africa (AFR), Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) and Arab States (ARB) respectively; by analyzing their spatial disparities and adopting a 15-year cycle counting backwards from 2023, four time periods can be identified: 1978, 1979–1993, 1994–2008, and 2009–2023. Subsequently, the spatio-temporal evolution laws of the threat intensity of karst WNHS are summarized. Finally, a threat assessment and outlook for each geographic region is provided.

Research methods

In this paper, the literature research method is employed for the statistical analysis. The TIC method was applied in obtaining the resultant data, and the method of combining quantitative analysis and qualitative analysis was used in analyzing the data. Through these research methods, the following tasks were carried out: obtaining data on research subjects and indicators; calculating the weights of the indicators; and conducting integrated analyses and assessments.

Obtaining data on research subjects and indicators

To begin with, the research object was determined. The information on karst landform, rocks, and other related features was extracted by reviewing a large amount of literature, and 31 karst-related WNHS were selected through this information in the List published by WHC. Furthermore, for these 31 karst WNHS, the selection time, geographical location, criteria met, and SOC reports were counted. Then, in line with UNESCO’s regional classification criteria, the number of karst WNHS in the five major geographical regions and the number of SOC reports submissions associated with each factor were counted.

Calculating the weights of the indicators

TIC33,34 was proposed in 2007 to assess the extent of harm to the OUV of WNHS caused by each factor that affects it. In order to determine the level of protection of karst WNHS in each region of the world, the TIC for karst WNHS was computed.

There are a total of 14 affecting factors in karst WNHS to be counted (Table 2). The number of SOC reports submitted each year in each region and the relevant affecting factors were counted. Taking a 15-year cycle, count backwards in time from 2023 and divide the time into four periods: 2009–2023, 1994–2008, 1979–1993, and 1978. Due to the timeliness of the submission time of SOC reports, each time period is divided into three stages. For the recent SOC reports submission of this factor within the 1–5 year period, a weighting of 12 points is assigned; for the period within 5–10 years, a weighting of five points is assigned; and for the period within 10–15 years, a weighting of three points is assigned35. Then the scores of each factor were added up in each region within each time period to obtain Fi. Finally, the TIC was calculated.

The formula is as follows:

Where the TIC is the value of threat intensity. Fi represents the result of the weighted sum of the number of SOC reports submitted for each factor in each geographical region within the time period. n is the number of WNHS in the region in each time period. The value range of TIC is between 0 and 100, with two decimal places reserved. The larger the value is, the greater the threat intensity of this factor to the heritage in this area. According to the above calculation steps, the threat intensity of each factor for each karst WNHS was determined.

Conducting integrated analyses and assessments

Based on the above steps, the spatial and temporal divergence regularity of the level of threat to karst WNHS was analyzed. Then the level of threat to karst WNHS in different regions was assessed with a 0–10 scale (Table 3). The threat intensity of each factor affecting karst WNHS is translated into a threat level scale, with 0 indicating no threat, 1 indicating the least threat, and 10 representing the greatest threat, with intermediate scores indicating different levels of severity. Finally, the literature and relevant documents were reviewed related to the heritage sites and threats, challenges, destruction, development, etc. Qualitative Literature Research Method and Expert Consultation Method were used to understand the level of threats to karst WNHS in each geographic region, as well as the threats and challenges they face.

Results

Global distribution and characteristics of karst WNHS

By 2023, due to their unique karst characteristics36, 31 WNHS have been inscribed on the List (Table 4). Among them, there are 28 World Natural Heritage Sites and three Mixed Heritage Sites. These sites are distributed in 22 States Parties. Moreover, these sites exhibit distinct spatial and temporal patterns:

This study quantified karst WNHS in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres as well as in the Eastern and Western Hemispheres using latitudinal ranges. The Earth is divided into the Northern and Southern Hemispheres by the equator (0° latitude). North of the equator is the Northern Hemisphere, and south of the equator is the Southern Hemisphere. 87% (27) of karst WNHS are in the Northern Hemisphere (Fig. 1). The area east of 20°W and west of 160°E is the Eastern Hemisphere, and the area west of 20° W and east of 160°E is the Western Hemisphere. 81% (25) of karst WNHS are in the Eastern Hemisphere. In terms of geographic distribution, APA has the majority (15 karst WNHS, 49%), followed by EUR (14 karst WNHS, 45%). Moreover, AFR and LAC each have a karst WNHS, and there are no karst WNHS in ARB (Fig. 1). This distribution reflects the uneven global distribution of carbonate rock formations.

a Spatial distribution of karst WNHS. Green circles represent WHNS and yellow circles represent mixed WHS. 1 Australian Fossil Mammal Sites(Riversleigh/Naracoorte), 2 Huanglong Scenic and Historic Interest Area, 3 Jiuzhaigou Valley Scenic and Historic Interest Area, 4 Wulingyuan Scenic and Historic Interest Area, 5 Three Parallel Rivers of Yunnan Protected Areas, 6 South China Karst, 7 Gunung Mulu National Park, 8 Rock lslands Southern Lagoon, 9 Puerto-Princesa Subterrancan River National Park, 10 Jeju Volcanic lsland and Lava Tubes, 11 East Rennell, 12 Dong Phayayen-Khao Yai Forest Complex, 13Ha Long Bay-Cat Ba Archipelago, 14 Phong Nha-Ke Bang National Park, 15 Trang An Landscape Complex, 16 Pirin National Park, 17 Nahanni National Park, 18 Plitvice Lakes National Park, 19 Pyrénées-Mont Perdu, 20 Caves of Aggtelek Karst and Slovak Karst, 21 The Dolomites, 22 Evaporitic Karst and Caves of Northern Apennines, 23 Durmitor National Park, 24 Lena Pillars Nature Park, 25 Škocjan Caves, 26 Henderson Island, 27 Dorset and East Devon Coast, 28 Mammoth Cave National Park, 29 Carlsbad Caverns National Park, 30 Desembarco del Granma National Park, 31 Andrefana Dry Forests. b Percentage of karst WNHS in different geographic regions.

In terms of criteria compliance. Over 80% of karst WNHS on the List meet the Criteria (vii) (“natural beauty”) and (viii) (“geological significance”) (Fig. 2, Table 1), underscoring their dual value as aesthetic landmarks and scientific resources37.

In terms of temporal trends. The number of karst WNHS inscribed on the List until the third period (1994–2008) increased linearly and then decreased.

Firstly, this is because most of the OUV of karst had already been inscribed on the List prior to 2008. Since then, the OUV of karst WNHS inscribed on the List has been distinct from previously inscribed karst features. For example, the Rock Islands Southern Lagoon’s OUV highlights the special value of the limestone islands in conjunction with the sea and lakes. Similarly, the Trang An Landscape Complex is a globally unique presentation of the final stages of the evolution of tower limestone landscapes in a humid tropical environment, among others.

Secondly, the introduction of the Cairns Decision at the 24th session of the WHC-Committee, which comes in the context of an increasing number of nominations for WHS, has seriously inhibited the nomination process in many countries and regions, especially in large heritage countries like China38. The 28th session of the WHC-Committee revised the Cairns Decision, which restricts nominations to countries with a large number of WHS39,40. This makes it more difficult for countries that already have WHS to reapply for World Natural Heritage41.

Thirdly, in 2021, the 44th session of the WHC-Committee adopted the 2021 version of the Operational Guidelines. This is the biggest revision of the content in the recent 10 years. The revision includes the addition of a preliminary assessment process. The revision implements the quantitative limit and priority principle of preliminary assessment along the lines of the formal nomination. The revision also adds a limit on the number of preliminary assessments to be submitted by States Parties per year (Each State Party shall submit to the WHC no more than one preliminary assessment per year by 15 September), and increases the limit on the total number of projects to be assessed by the Advisory Bodies42,43. These reasons have led to a gradual decrease in the number of applications for WHS each year.

Threat factors and their spatial-temporal evolution

The WHC-Committee has adopted a specific procedure to encourage States Parties to conserve WHS. RM is the monitoring of anomalies or risk factors that threaten the conservation of WHS. Its purpose is to discover and solve the problems arising in WHS protection in a timely manner, and ensure that the outstanding universal value of WHS is effectively protected and transmitted to future generations. RM is defined in Paragraph 169 of the Operational Guidelines as being “the reporting by the WHC, other sectors of UNESCO and the Advisory Bodies to the WHC-Committee on the state of conservation of specific WHS that are under threat”4.

A standard list of factors affecting OUV in WHS was identified by WHC in the process of revising the questionnaire for the second cycle of Periodic Reporting in 2008 (Table 2). It comprises 14 primary factors and some secondary factors. The primary factors can be divided into two categories: human factors and natural factors. There are nine human factors F1-9, and four natural factors F10-13. There is also one factor named other factors, which refers to the factors affecting that are not involved in addition to the above common affecting factors. Subsequently, the State of Conservation Information System was established by the WHC-Committee in 2013 to provide information on the state of conservation of WHS for conservation management44. This provides an important basis and guidance for the nomination, assessment and conservation of WHS.

As of December 31, 2023, the number of global karst WNHS inscriptions on the List is gradually decreasing, and while the number of SOC reports is on an overall upward trend, with a total of 169 (Fig. 3). APA has submitted the most SOC reports, accounting for 51% of the global total. EUR accounts for 48% of SOC reports. As the number of karst WNHS inscribed on the List varies from one geographic region to another, the number of SOC reports varies from one region to another. The number of karst WNHS in each geographic region is directly proportional to the number of SOC reports they have submitted (Fig. 4).

Yellow columns represent the annual total number of SOC report submissions for Karst WNHS. The green columns represent the annual total number of inscribed Karst WNHS. The sloping yellow transparent line represents the overall direction of change in the number of SOC reports from 1977 to 2023. The sloping green transparent line represents the overall direction of change in the number of inscribed Karst WNHS.

Yellow columns represent the total number of SOC report submissions by region. The green columns represent the total number of inscribed Karst WNHS by region. The yellow line represents the variation in the number of SOC reports from different regions. The green line represents the change in the number of Karst WNHS in different regions.

Threat intensity increased globally from 1979 to 2023, with TIC rising from 0 (1978) to 23.83 (2009–2023), yet significant regional disparities exist. Human activities, particularly management and institutional factors (F9) and social/cultural uses of Heritage (F7), drove this trend (Fig. 5). In the APA region, the TIC has been climbing steadily, reaching a peak of 32.9 from 2009 to 2023. This is mainly driven by insufficient management mechanisms and tourism pressure. In the EUR region, the TIC has been gradually brought under control since 1994, with threats concentrated on tourism development and planning and management issues.

It reflects the TIC for each geographic region for different time periods. a The TIC of 14 kinds of factors in different geographical regions during 1979–1993; b The TIC of 14 kinds of factors in different geographical regions during 1994–2008; c The TIC of 14 kinds of factors in different geographical regions during 2009–2023.

Threat Intensity in 1978. Since the establishment of the Convention, the year 1978 was the first year in which WHS were inscribed on the List. This year the only karst WNHS was Nahanni National Park in Canada. The first SOC report for karst WNHS was in 1984. TIC for this period is unknown and is recorded by the authors as 0.

Threat Intensity in 1979–1993. The data show that karst WNHS are threatened by six factors, all of which are human factors. EUR is the most threatened, mainly involving services infrastructures (F3), pollution (F4) and other human activities (F8). F3 and F4 only threaten the Durmitor National Park. F8 only threatens Plitvice Lakes National Park. All other threat factors have a threat intensity of less than 10.

Threat Intensity in 1994–2008. The data reveal a marked escalation in cumulative threat levels across global karst WNHS compared to the preceding observational period. Thirteen distinct threat factors were identified during this cycle, comprising nine human factors and four natural factors. Notably, both EUR and APA regions exhibited vulnerability to 12 concurrent threat categories, with management and institutional factors (F9) and social/cultural uses of Heritage (F7) emerging as predominant stressors.

Global-scale analysis demonstrates that management and institutional factors (F9) registered the most substantial TIC increment, concurrently maintaining peak TIC values throughout the study period. This factor adversely affected 15 karst WNHS, as evidenced by its consistent documentation in SOC reports submitted to the WHC for properties including Henderson Island and Pyrénées-Mont Perdu. Secondary threat prevalence was associated with social/cultural uses of Heritage (F7). This threat factor pertains to 10 karst WNHS. Representative cases encompass Ha Long Bay-Cat Ba Archipelago, Pirin National Park, Durmitor National Park, and the aforementioned Pyrénées-Mont Perdu. Remaining threat factors demonstrated limited spatial influence, all recording TIC values below threshold significance levels (TIC < 10).

Threat Intensity in 2009–2023. The data indicate that Karst WNHS are subject to threats from 12 distinct factors during the period 2009–2023. Notably, sudden ecological or geological events (F12) were absent in this period, unlike in previous years. Among these threats, nine are human factors and three are natural factors. These threats predominantly affect the APA, with all 12 factors present, compared to only nine in the EUR, marking a reduction of three factors from the preceding period. APA is primarily threatened by management and institutional factors (F9), social/cultural uses of Heritage (F7), buildings and development (F1), biological resource use/modification (F5); while EUR is threatened by (F7), (F1), (F9).

The factor with the highest threat intensity remains management and institutional factors (F9), which threaten 12 Karst WNHS. The TIC for F9 in the APA has escalated by nearly 50% compared to the previous period, whereas it has declined in the EUR. Key sites threatened by F9 include the Three Parallel Rivers of Yunnan Protected Areas, East Rennell, Dong Phayayen-Khao Yai Forest Complex, Ha Long Bay-Cat Ba Archipelago, and Phong Nha-Ke Bang National Park. The second most significant threat is social/cultural uses of Heritage (F7), threatening 11 Karst WNHS, with an observed increase in threat intensity from the previous period. Major sites threatened by F7 include Pirin National Park, Dong Phayayen-Khao Yai Forest Complex, and Ha Long Bay-Cat Ba Archipelago. Following F7, buildings and development (F1) constitute the third major threat, threatening seven Karst WNHS, with an increased threat intensity noted from the previous period. Significant threats to F1 are observed at Pirin National Park and Ha Long Bay-Cat Ba Archipelago. Although these top three factors threaten fewer sites compared to earlier periods, the intensity of their threat to each affected site has increased. The fourth most significant threat factor is biological resource use/modification (F5), which threatens three karst WNHS. East Rennell, Dong Phayayen-Khao Yai Forest Complex and Three Parallel Rivers of Yunnan Protected Areas are threatened by F5. Remaining threat factors demonstrated limited spatial influence, all recording TIC values below threshold significance levels (TIC < 10).

Temporal Shifts in Threat Dynamics. In 1979–1993, human-driven threats (F3, F4, F8) emerged in EUR, with a low TIC (<10). In 1994–2008, a rapid escalation of F9 (management) and F7 (tourism) occurred, particularly in APA. In 2009–2023, APA TIC surged (32.9 for F9), while EUR stabilized through policy interventions. Natural factors (e.g., climate change) remained secondary but are rising in APA (Fig. 5).

Assessment of threat intensity and conservation outlook for karst WNHS

Given the absence of TIC data in 1978, this section focuses on comparative analyses of three chronological phases: 1979–1993, 1994–2008, and 2009–2023. The TIC data were classified into threat levels based on geographic regional categorization (Fig. 6).

The first karst WNHS in APA was inscribed in 1992, with the inaugural SOC report submitted in 1995. Consequently, our analysis covers 1994-2008 and 2009–2023. Current data (2023) identifies 15 karst WNHS in APA, affected by 13 threat factors (nine human factors, four natural factors).

According to the classification in Table 3 and Fig. 6, Level 4 (the highest level): Factor F9 threatens 12 WNHS with 66 associated SOC reports. Level 3: Factor F7 affects 10 WNHS with 45 SOC reports. Level 2: Factors F1, F2, F3, F5, F6, F14. Level 1/Below: Remaining factors.

Key case studies. Ha Long Bay-Cat Ba Archipelago (18 SOC reports): Primary threats come from F1, F2, F7, and F9. However, proactive measures include WHC-recognized management plans (2021–2025), serving as regional best practice. Three Parallel Rivers (14 SOC reports): Key challenges include F3, F6, and F9-related issues such as ambiguous boundaries, unauthorized infrastructure, and adjacent mining activities. East Rennell (14 SOC reports): Listed as Endangered (2013–present) due to F5, F6, F9, F11, F13 threats. It is mainly due to marine overexploitation, storm impacts, and invasive species. Dong Phayayen-Khao Yai Complex (12 SOC reports): Multiple pressures from F2, F3, F5, F7, F9, F14, including highway expansion, illegal logging, and dam construction.

APA demonstrates higher threat complexity than other regions, particularly through F9 (global maximum threat level) and escalating F7 threats. Urgent collaborative mitigation strategies are required.

The 14 karst WNHS in EER are confronted with 12 threat factors, among which nine are human-related and three are natural. Based on the current threat hierarchy presented in Fig. 6, at Level 3, Factor F7 poses a threat to 5 WNHS and is associated with 47 SOC reports. At Level 2, the threat factors are F1 and F9. As for Level 1/Below, it encompasses the remaining factors.

Key case studies. Pirin National Park (20 SOC reports): There is tourism infrastructure expansion despite environmental concerns related to factors F1, F7, F8, F9. Durmitor National Park (16 SOC reports): Ski resort development poses threats due to factors F1, F3, F7, F9. Plitvice Lakes National Park (12 SOC reports): It faces primarily F7-related overvisitation pressures.

While EUR shows better overall conservation status than APA, monitoring is crucial for F7 (increasing trend) and F1. Successful F9 mitigation should be maintained.

In AFR the single WNHS (Andrefana Dry Forests) resolved its 1992 financial/management challenges through World Bank support (US$85,000), with no current SOC reports indicating threats.

There is also only one Heritage Site in the LAC, Desembarco del Granma National Park, for which no SOC report has been filed to date, so it is unclear whether it is threatened, and this paper considers that there is no threat for the time being.

Discussion

This study evaluates the threat intensity to karst WNHS globally, analyzing their spatiotemporal patterns and conservation challenges. The findings are summarized as follows:

The number of WNHS on the List with typical karst features as the OUV totals 31 by the end of 2023. They are characterized by the following features: Most sites meet criteria (vii) (aesthetic significance) and (viii) (geological integrity). Karst WNHS occupies a relatively large proportion in the northern and eastern hemispheres, 87% and 81%, respectively. The number of karst WNHS in each geographic region is directly proportional to the number of SOC reports they submit. APA leads with 15 karst WNHS (49%), followed by EUR with 14 combined (45%). AFR and LAC each have one site (3%), while ARB lacks karst WNHS. Inscriptions peaked during 1994–2008, followed by a decline post-2009.

World Heritage monitoring is an indispensable requirement for strengthening heritage conservation and an important way to increase the level of heritage management45. In 1998, the WHC-Committee required States Parties to submit periodic reports on their subordinate WHS to the WHC every 6 years46. Global WHS need to be subjected to periodic reports of conservation and management of the WHS and RM, which places greater demands on States Parties to conserve, monitor, and manage the World Natural Heritage47. The SOC report is a component of conservation management efforts. The WHC has established a World Heritage Conservation Status System that identifies a total of 14 factors affecting karst WNHS.

As of 2023, among the factors affecting karst WNHS, 13 are relevant to karst WNHS. Nine are human factors and four are natural, with human factors posing a far greater threat. Compared with the results of a previous study, there was an increase in F11 for natural factors33, but again, the number of human factors is much greater than that of natural factors in terms of both variety and number of threats to WHS. This indicates that governance and development pressures are critical challenges.

The global development of karst WNHS has been divided into four phases, based on when sites were inscribed on the List: 1978, 1979–1993, 1994–2008 and 2009–2023. There are spatial and temporal differences in the intensity of threats to the global karst WNHS due to differences in the number, distribution, and monitoring of heritage sites over time.

The year 1978 was the Initial Phase. The inaugural year of World Heritage inscription saw only one karst WNHS: Nahanni National Park in Canada. No SOC reports were submitted for karst sites during this period, resulting in a TIC of zero.

The period from 1979 to 1993 was the Exploratory Phase. Eleven karst WNHS were inscribed globally during this period, with seven in EUR, three in APA, and one in AFR. Only three properties in EUR (Durmitor National Park, Plitvice Lakes National Park, Škocjan Caves) and one in AFR (Andrefana Dry Forests) have submitted SOC reports. Threat analysis revealed low-intensity pressures, with six human factors emerging. Durmitor National Park faced two threats, while others were affected by one factor. The highest TIC values were observed for Factor 3 (TIC = 11.5) and Factor 4 (TIC = 10.25), with the remaining factors below 10. Overall, conservation statuses remained favorable.

The period from 1994 to 2008 was the Rapid Expansion Phase. Fifteen new karst WNHS were inscribed, predominantly in APA (10 sites), followed by EUR (4) and LAC (1). Threat diversity and intensity increased significantly, with seven new factors emerging. F9 and F7 became prominent threats, while TIC values for F3, F4, and F8 declined. Notably, F9 and F7 exhibited rising TICs, though no new factor exceeded TIC = 10. Conservation statuses remained stable except for sites threatened by F7 and F9.

The period from 2009 to 2023 was the Maturation Phase. Five new karst WNHS were added (3 in EUR, 2 in APA). Threat types stabilized, but intensity escalated sharply. All factors except F12 showed increased TICs, signaling deteriorating conservation statuses. In EUR, F7 emerged as the primary threat (TIC = 21.83), followed by F1 (TIC = 18.67) and F9 (TIC = 18.17). The APA faced acute pressures from F9 (TIC = 32.9), F7 (TIC = 20.8), and F5 (TIC = 16.5), with eight factors exceeding TIC = 10. Regional disparities became pronounced: EUR demonstrated improved threat mitigation since the second phase, while APA experienced linear intensification. AFR’s singular threat (TIC = 1) disappeared post-1993, and other regions currently face negligible pressures.

From 1978 to 2023, the cumulative TIC growth was highest for F9, followed by F7 and F1. While global threat intensity trends upward, only the APA exhibits a linear increase. EUR achieved threat mitigation post-1993, whereas AFR’s minor threat was resolved entirely. These findings underscore the need for region-specific conservation strategies, particularly in the APA, where management efficacy lags behind EUR.

Evaluation of threat severity affecting karst WNHS reveals that the APA region faces disproportionately high pressures, with most threat factors exceeding level 2 on the intensity scale. Sites exhibiting suboptimal conservation status include Three Parallel Rivers of Yunnan Protected Areas, East Rennell, and Ha Long Bay-Cat Ba Archipelago, where primary threats stem from factors F7 (tourism impacts), F1 (infrastructure development), and F9 (institutional management deficiencies). In contrast, EUR karst WNHS such as Pirin National Park, Durmitor National Park, and Plitvice Lakes National Park demonstrate lower cumulative pressures, with minimal high-intensity threats. Other geographic regions currently maintain stable conservation conditions.

Thirteen distinct threat factors threaten APA karst WNHS, with F9 (management system deficiencies) and F7 (tourism pressures) reaching intensity levels 4 and 3, respectively. Institutional weaknesses manifest as insufficient management planning, inadequate resource allocation, and limited technical capacity, correlating strongly with national socioeconomic disparities and heritage investment priorities48. Case analyses reveal:

Three Parallel Rivers of Yunnan: Infrastructure projects caused 22–35% declines in keystone species populations; Dong Phayayen-Khao Yai Forest Complex: Road expansion reduced core habitat connectivity; Ha Long Bay-Cat Ba Archipelago: Absence of integrated zoning increased non-compliant coastal development; Australian Fossil Mammal Sites: Tourism infrastructure gaps enable in situ fossil degradation.

F7-related pressures predominantly involve unregulated tourism growth, exemplified by Phong Nha-Ke Bang National Park’s cave tramway project increasing microclimate fluctuations, and Ha Long Bay’s visitor increase driving unplanned urbanization. Secondary threats (F1, F2, F3, F5, F6, F14) show concerning upward trajectories requiring proactive monitoring.

Twelve threat factors affect EUR karst WNHS, with F9 and F7 persisting as primary concerns at reduced intensities (level 3 and 2). Management challenges center on legal framework gaps (F9) and seasonal tourism impacts (F7):

Pirin National Park: Ski resort expansions degraded alpine ecosystems; Durmitor National Park: Proposed dam projects threatened endemic aquatic species; Plitvice Lakes National Park may be overvisited by tourists.

Notably, EUR has implemented IUCN-recommended carrying capacity models, demonstrating improved regulatory responsiveness compared to APA counterparts.

For APA, it is recommended to strengthen institutional frameworks, enforce sustainable tourism strategies, and address infrastructure pressures. Maintain vigilance on tourism impacts and legal enforcement for EUR. Globally, it is necessary to prioritize standardized monitoring, capacity building, and transboundary collaboration.

This study fills a critical gap in karst WNHS threat analysis, providing the first comparative framework for prioritizing management interventions by threat magnitude, standardizing SOC reporting metrics across biogeographic regions, and providing a foundation for targeted conservation strategies. However, it is important to acknowledge several limitations of this research.

Firstly, this study’s data mainly comes from existing reports and monitoring data, which could be incomplete or inaccurate in certain regions. Karst WNHS in remote or underdeveloped areas may lack comprehensive and updated information, possibly causing misjudgment of threat factors and their impacts.

Secondly, the comparative framework simplifies the complex, non-linear interactions and cumulative effects among threat factors on karst WNHS. Thus, the current analysis fails to fully capture these relationships.

Finally, the proposed recommendations are based on the current understanding of threats and conservation needs. Given the constantly changing global social, economic, and environmental conditions, their effectiveness may decline over time.

Future work should integrate socioecological metrics to refine risk forecasting and also address these limitations to enhance the accuracy and applicability of the research findings.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- WHS:

-

World Heritage Sites

- OUV:

-

Outstanding Universal Value

- List:

-

World Heritage List

- Convention:

-

Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage

- WHC-Committee:

-

World Heritage Committee

- WHC:

-

World Heritage Center

- RM:

-

Reactive Monitoring

- Operational Guidelines:

-

The Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention

- UNESCO:

-

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

- TIC:

-

Threat Intensity Coefficient

- SOC:

-

State of Conservation

- WNHS:

-

World Natural Heritage Sites

- IUCN:

-

International Union for Conservation of Nature

- APA:

-

Asia & Pacific

- EUR:

-

Europe and North America

- AFR:

-

Africa

- LAC:

-

Latin America and Caribbean

- ARB:

-

Arab States

References

Zeng, C. & Luo, J. Review and prospects of International World Heritage monitoring. Relics Museol 25, 47–52 (2008).

Zhou, H. & Luo, J. On the establishment of the monitoring and controlling system for the management of China’s World Heritage. J. Southwest Jiaotong Univ. (Soc. Sci.)5, 31–4+44 (2004).

UNESCO. Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. https://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/. Accessed 15 Mar 2024 (1972).

UNESCO. The operational guidelines for the implementation of the World Heritage Convention. https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/. Accessed 15 Mar 2024. Accessed 15 Mar 2024 (2023).

UNESCO. Managing natural world Heritage (World Heritage resource manual). https://whc.unesco.org/en/managing-natural-world-heritage/. Accessed 10 Feb 2024 (2015).

UNESCO. World Heritage List. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/. Accessed 10 Feb 2024.

UNESCO, ICCROM, ICOMOS, IUCN. Guidance and toolkit for impact assessments in a World Heritage Context. https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidance-toolkit-impact-assessments/. Accessed 20 Mar 2024 (2022).

Lyu, Z. The 44th session of the World Heritage Committee and the value and significance of the convention concerning the protection of the world cultural and natural heritage. Study Nat. Cult. Herit. 7, 1–5 (2022).

UNESCO. Strengthening the effectiveness of the world heritage reactive monitoring process. https://whc.unesco.org/en/173/. Accessed 10 Feb 2024 (2019).

Goldscheider, N., Chen, Z., Auler, A. S., Bakalowicz, M., Broda, S. & Drew, D. et al. Global distribution of carbonate rocks and karst water resources. Hydrogeol. J. 28, 1661–77 (2020).

Luo, W. & Liu, Y. Ghostly Karst caves. Bull. Min. Petrol. Geochem. 43, 1–6 (2024).

Cui, J., Wen, Q. & Huang, J. Comprehensive management of stony desertification in Karst areas. Soil Water Conserv. China. 45, 49–52 (2024).

Jia, X., Yang, S., Wei, C. & Yu, Y. Basic characteristics and research progress of Karst Environment. J. Jishou Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 46, 58–67 (2024).

Yuan, D. et al. Karst in southwestern China and its comparison with karst in northern China. Quat. Sci. 9, 352–361 (1992).

Tu, C., Luo, W., Li, F., Yue, X., Liu, P. & Wu, Z. Spatial and temporal changes of karst rocky desertification and its cause analysis in South China. Geol. Bull. China. 44, 326–339 (2025).

Peng, X. & Dai, Q. Drivers of soil erosion and subsurface loss by soil leakage during karst rocky desertification in SW China. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 10, 217–27 (2022).

Wen, H., Liu, E., Yan, S., Chang, J., Xiao, N., Zhou, J. Conserving Karst Cavefish Diversity in Southwest China. Biol. Conserv. 273 (2022)

Wang, K., Yue, Y., Chen, H., Wu, X., Xiao, J. & Qi, X. et al. The comprehensive treatment of karst rocky desertification and its regional restoration effects. Acta Ecol. Sin. 39, 7432–40 (2019).

Yuan, D. Global view on Karst rock desertification and integrating control measures and experiences of China. Pratacult. Sci. 23, 352–361 (2008).

D’ettorre, U., Liso, I. & Parise, M. Desertification in karst areas: a review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 253, 19 (2024).

Gunn, J. Karst groundwater in UNESCO protected areas: a global overview. Hydrogeol. J. 29, 297–314 (2021).

He, G., Zhao, X. & Yu, M. Exploring the multiple disturbances of karst landscape in Guilin World Heritage Site, China. Catena 203, 11 (2021).

Lewis, I. South Australian geology and the State Heritage Register: an example of geoconservation of the Naracoorte Caves complex and karst environment. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 66, 785–92 (2019).

Van, D., Adams, J., Durand, J., Grobler, R., Grundling, P. & Van, R. et al. Conservation conundrum—Red listing of subtropical-temperate coastal forested wetlands of South Africa. Ecol. Indic. 130, 14 (2021).

Zhang, N., Xiong, K., Zhang, J. & Xiao, H. Evaluation and prediction of ecological environment of Karst World Heritage Sites based on google earth engine: a case study of Libo-Huanjiang karst. Environ. Res Lett. 18, 9 (2023).

Chen, P., Xiong, K. & Xiao, S. Global comparative analysis on the world natural heritage values of Libo cone karst in China. Geogr. Res. 32, 1517–27 (2013).

Xiong, K., Zhang, Z., Xiao, S., Di, Y., Xiao, H. & Zhang, Y. et al. Impact of Guinan railway construction on the geomorphologic value of the Libo-Huanjiang Karst World Heritage Site. Trop. Geogr. 40, 466–77 (2020).

Cech, V., Chrastina, P., Gregorova, B., Hroncek, P., Klamar, R. & Kosova, V. Analysis of attendance and speleotourism potential of accessible caves in Karst Landscape of Slovakia. Sustainability 13, 21 (2021).

Pang, W., Pan, Y., You, Q., Cao, Y., Wang, L. & Deng, G. et al. Causes of aquatic ecosystem degradation related to tourism and the feasibility of restoration for karst nature reserves. Aquat. Ecol. 56, 1231–43 (2022).

Sunkar, A., Lakspriyanti, A., Haryono, E., Brahmi, M., Setiawan, P. & Jaya, A. Geotourism hazards and carrying capacity in geosites of Sangkulirang-Mangkalihat Karst, Indonesia. Sustainability 14, 26 (2022).

Xu, Z., Shu, X., Cao, Y., Xiao, Y., Qiao, X. & Tang, Y. et al. Wet deposition of sulfur and nitrogen in the Jiuzhaigou World Heritage Site, China: Spatial variations, 2010-2022 trends, and implications for karst ecosystem conservation. Atmos. Res. 297, 11 (2024).

IUCN. IUCN World Heritage Outlook 3: A Conservation Assessment of All Natural World Heritage Sites. https://iucn.org/resources/publication/iucn-world-heritage-outlook-3. Accessed 31 Jan 2024 (2020).

Hong, S. Factors affecting Karst World Natural Heritage properties in the world and the threat intensity. Guizhou Normal University. https://doi.org/10.27048/d.cnki.ggzsu.2021.000186 (2021).

Wang, Z., Yang, Z., Han, F., Luan, F., Li, D. & Duan, Z. Spatial-temporal evolution of the security pattern of world natural heritage and the threats in China. Arid Land Geogr. 38, 833–42 (2015).

Marc, P., Clare B., Benedicte L. The state of conservation of world heritage forests. World heritage series: reports. 21, https://whc.unesco.org/en/documents/8790. Accessed 10 Jan 2024 (2005).

Xiong, K., Zhang, S., Fei, G., Jin, A. & Zhang, H. Conservation and sustainable tourism development of the natural World Heritage Site based on aesthetic value identification: a case study of the Libo Karst. Forests 14, 25 (2023).

Zhong, Y., Xiong, K. & Du, F. Landscape aesthetic value of nominated Huanjiang Karst World Heritage and its comparative analysis based on World Heritage Criteria (vii).J. Kunming Univ. Sci. Technol. (Nat. Sci.) 39, 25–32 (2014).

Li, X. How to break through the Keynes resolution. Urban Rural Dev. 50, 27–30+5 (2005).

Shi, C. New tendency in the World Heritage Conservation. World Archit. 25, 80–2 (2004).

Zhang, R., Zhang, X., Jiang, J. & Ge, Y. Study on tendency and potential of World Natural Heritage. Geogr. Geo-Inf. Sci. 22, 57–61 (2006).

Li, J., Zhang, X. & Zheng, S. Tourism Tribune. Tour. Tribune 21, 86–91 (2006).

Tian, X., Chen, K. & Sun, Y. Study on natural and cultural heritage. Study Nat. Cult. Herit. 7, 92–102 (2022).

Williams, P. Karst in UNESCO World Heritage Sites[M]. Karst Management. 459–480 (2011).

Min, Q., Zhao, G. & Jiao, W. Progress of world heritage monitoring and evaluation and enlightenments to China’s agriculture heritage systems management. World Agric. 28, 1350–1360 (2020).

Jiao, W., Zhao, G., Min, Q., Liu, M. & Yang, L. Building a monitoring system for Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems(GIAHS) based on the monitoring experience of World Heritage. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 28, 1350–60 (2020).

Zhuang, Y. Preliminary comments on 2nd cycle world heritage periodic reporting. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 28, 97–100 (2012).

Xiang, B., Wen, T., Guo, H., Liu, H. & Liu, Z. Research on platform design scheme of natural heritage monitoring and protection management based on spatiotemporal data fusion. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 36, 95–9 (2020).

Lu, J., Chen, X., Zhao, D. & Wang, Q. A discussion on the challenges in the conservation and management of natural landscapes from the perspective of world natural heritage. Study Nat. Cult. Herit. 9, 85–94 (2024).

UNESCO. The criteria for selection. https://whc.unesco.org/en/criteria/. Accessed 10 Feb 2025.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of Guizhou Normal University. This work was supported by Guizhou Provincial Key Technology R&D Program: A study on the conservation model with technology and sustainable development demonstration of the World Natural Heritages in Guizhou (No. 220 2023 QKHZC), the China Overseas Expertise Introduction Project for Discipline Innovation (China 111 Project) [grant number: D17016]. Moreover, the authors are also grateful to the editors and anonymous reviewers for their opinions and comments to be provided on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the manuscript. Conceptualization, M.Q.S., S.Y.H., and S.Z.X.; methodology, S.Y.H.; validation, M.Q.S.; analysis, M.Q.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Q.S.; writing—review and editing, M.Q.S., and S.Z.X.; visualization, M.Q.S. and Q.Q.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, M., Hong, S., Meng, J. et al. Assessment and outlook of the global karst World Natural Heritage Sites based on threat intensity. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 180 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01768-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01768-x