Abstract

Minnan nursery rhymes (MNRs), an integral part of Minnan intangible cultural heritage (ICH), are shared by southern Fujian, Taiwan, and overseas Chinese communities. Preserving and analyzing MNRs, especially their emotional evolution over time, is crucial but challenging due to shifting cultural contexts. Traditional sentiment analysis methods often overlook intrinsic relationships among nursery rhymes. To address this, we construct an MNR network using textual feature vectors and cosine similarity thresholds, enabling the exploration of structural and emotional patterns. Inspired by graph neural networks, we propose a Joint-GraphSAGE model for sentiment classification, which effectively captures complex relationships and semantic nuances. Comparative experiments with classical machine learning and deep learning models demonstrate that the Joint-GraphSAGE model significantly outperforms baselines in sentiment classification tasks for both traditional and modern MNRs. This approach not only enhances sentiment analysis accuracy for MNRs, but also offers new perspectives for studying ICH cultural connections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intangible cultural heritage (ICH) refers to cultural elements passed down through generations, including performing arts, social practices, rituals, festivals, and oral traditions and expressions1. As a typical form of ICH, Minnan nursery rhymes (MNRs) are children’s rhymed verses recited in the Minnan dialect, representing a form of folk oral literature2. MNRs were recognized as a form of art in the domain of “Oral Traditions and Expressions” by UNESCO in the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the ICH3. The preservation and research of Minnan ICH has the potential to positively impact society, the economy, and the environment. And the aim of MNR's research is to secure the perpetuation and evolution of these traditions, thereby enriching the diversity within Minnan culture.

The singing language of MNRs, a vital branch of the Chinese language, retains many ancient features reflecting its long history and culture. Therefore, many scholars consider MNRs as a carrier of the living linguistic fossil4. In addition, MNRs embody rich historical heritage and national sentiment, tracing back to the Tang Dynasty5,6,7. They reflect the cultural exchanges between Central Plains culture and Baiyue culture, carrying cultural information on the living conditions, social ethics, and folk customs of the Minnan people2,8. MNRs enjoy widespread popularity not merely within the Minnan region spanning Fujian, Guangdong Province, and Taiwan, but also extend their appeal to Minnan communities across Southeast Asia and worldwide9. Through the unique transmission mode of oral tradition, MNRs shape children’s speech, moral education, and historical perspective, becoming a crucial component of Minnan culture. They offer a distinctive and important cultural window for reminiscing, restoring, and understanding traditional Minnan culture, reflecting the wisdom, emotions, and spirit of the Minnan people10,11. To better protect this ICH, MNRs were included in the second batch of the National ICH list in 200812. Thus, the preservation, inheritance, and analysis of ICHs like MNRs, especially the emotional changes embedded in nursery rhymes over time, are crucial. Traditional methods of preserving MNRs rely on oral transmission and intergenerational transfer, which are challenging for preservation and research. Cultural globalization further complicates the challenges in preserving and promoting MNRs.

Nowadays, the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence technology has rendered digital culture indispensable for the preservation, analysis, and dissemination of ICH13. Digital formats such as text, audio, and images allow more individuals to gain profound insights into traditional cultures14. Advanced artificial intelligence technologies, notably machine learning, deep learning, and natural language processing, streamline systematic exploration of diverse cultural expressions, thereby bolstering the curation, analysis, and safeguarding of cultural heritage data15,16,17. Sentiment classification, also known as opinion mining, is a subfield of natural language processing that identifies and extracts subjective information from texts like online reviews and blogs, focusing on computationally analyzing opinions, sentiments, and subjectivity, which can be either positive or negative18,19. There are two main types of sentiment classification algorithms: lexicon-based and machine learning-based. Lexicon-based methods rely on predefined sentiment lexicons for sentiment classification. These methods are simple and interpretable, while their efficacy is often constrained by their inability to adequately capture context-dependent sentiment. Consequently, they may struggle to accurately classify sentiment in complex or domain-specific texts such as MNRs, which exhibit unique linguistic and cultural characteristics20. In contrast, machine learning-based approaches, including supervised methods like support vector machines (SVM) and decision trees, as well as unsupervised techniques, have shown promise in overcoming these limitations by learning complex patterns from data21. Experimental results have shown that supervised learning methods, such as SVM and naive Bayes, generally achieve higher accuracy22.

With the advancement of artificial intelligence, deep learning has emerged as a powerful approach in sentiment analysis, particularly for fine-grained sentiment classification. Deep neural architectures, such as convolutional neural networks (CNN), long short-term memory (LSTM), and their variants, have demonstrated superior performance by automatically capturing both syntactic and semantic features of text, effectively circumventing the limitations of traditional manual feature engineering approaches in aspect-based sentiment analysis23. Researchers have further enhanced the joint modeling performance of aspect extraction and sentiment polarity classification by incorporating pre-trained word embeddings, linguistic rules, and conceptual knowledge bases24. To address the issue of scarce labeled data, researchers have proposed attention-based CNN-BiLSTM hybrid models, which enhance the representation of complex semantic features through joint learning and transfer learning mechanisms. This approach has demonstrated significant improvements in classification accuracy through optimized data augmentation and attention weight distribution25.

Recently, graph neural network (GNN) models have demonstrated their efficacy in sentiment classification, further advancing the field. By leveraging GNNs such as graph convolutional networks (GCN)26 and graph attention networks (GAT)27, syntactic feature representations can be learned from dependency trees, leading to a more comprehensive understanding of sentence sentiment28. This approach addresses the limitations of traditional sentiment classification by incorporating both syntactic and semantic features, which has shown superior performance in tasks such as Weibo comment analysis and aspect-based sentiment classification. For instance, a GNN-LSTM model achieved 95.25% accuracy in analyzing Weibo comments by effectively capturing the semantic and syntactic features of sentences29. Additionally, methods like heterogeneous graph neural networks (Hete_GNNs) and attentional graph neural networks (AGN-TSA) have demonstrated improvements in sentiment classification and Twitter sentiment analysis, respectively, by integrating various context information30,31. GraphSAGE, a type of GNN, has emerged as a powerful approach for sentiment classification by leveraging graph structures to capture complex relationships and enhance textual data analysis. By incorporating diverse structural information, such as part-of-speech tags, syntactic dependencies, and co-occurrence patterns, GraphSAGE and similar GNN models significantly improve the extraction and interpretation of sentiment from short texts and social media data32,33. This advancement represents substantial progress in sentiment classification, overcoming the limitations of traditional methods and enabling a more nuanced understanding of texts. Specifically, this approach facilitates a detailed analysis of emotional content within MNRs, offering valuable insights into their cultural and historical contexts.

MNRs in the Minnan region exhibit a wide range of complex emotional expressions. Traditional machine learning and deep learning models usually treat nursery rhymes as independent entities for sentiment analysis, neglecting the interconnectedness among them. To address this issue, this paper proposes to construct a network structure for nursery rhymes, where GNNs can be employed to learn both the semantic content and the inter-textual relationships of nursery rhymes within a specific genre, thereby improving sentiment prediction accuracy. Specifically, we first collect and analyze two datasets of traditional and modern MNRs. We then build a network using the TF-IDF (term frequency-inverse document frequency) and Doc2vec (document to vector) method. Subsequently, we conduct a comprehensive network analysis based on complex network theory to gain a deeper understanding of the structure, pattern, and connotation of the MNR network. Finally, we propose a Joint-GraphSAGE model, tailored to the characteristics of MNRs, and compare it with mainstream machine learning methods (e.g., SVM34, LR35) and deep learning methods (e.g., CNN36, LSTM37, and Bi-LSTM38), as well as the classical GNN models (e.g., GraphSAGE39). The experimental results demonstrate that the Joint-GraphSAGE-based sentiment classification approach for MNRs significantly outperforms the baseline models. This analysis and results not only deepen our understanding of the interrelationships and characteristics of MNRs but also provide valuable insights and guidance for the preservation and exploration of Minnan culture.

Methods

Description of MNRs

Data collection of MNRs

The dataset used in this paper includes two types of MNRs: traditional and modern MNRs. Traditional MNRs are sourced from two compilations of Minnan folk songs: Selection of Singapore Minnan Folk Songs, edited by Changji Zhou and Qinghai Zhou, and Selection of Zhangzhou and Taiwan Minnan Folk Songs, edited by Yuping Jiang et al. Modern nursery rhymes are sourced from various musical platforms, including QQ Music, NetEase Cloud Music, and Migu Music. Following a rigorous process of manual selection and the removal of duplicates, we have assembled a total of 617 unique traditional nursery rhymes and 289 modern nursery rhymes. It is important to note that we only include nursery rhymes in Minnan dialect, so rhymes with pure Mandarin are excluded from this dataset. Overall, the dataset encompasses 14 sentiment genres. Table 1 displays the top five emotional categories and their respective quantities within the traditional and modern nursery rhyme collections.

Word cloud of MNRs

Word cloud analysis is a data visualization technique that highlights the most frequent terms in a text, providing visual insights into the thematic essence of MNRs. After segmenting the lyrics, a word cloud diagram for MNRs is generated, as depicted in Fig. 1. In this diagram, the size of each word is proportional to its frequency of occurrence in the lyrics. Thus, more common lyrical words will be larger and bolder, while less frequent words will be smaller.

Figure 1a reveals the frequent imagery words related to daily life, the natural environment, and cultural practices of the Minnan region within traditional MNRs, with lyrical terms like “Moonlight (月光光)", “Dark sky (天乌乌)", “Fireflies (火金姑)", “November (十一月)", and “Amitabha (阿弥陀福)" appearing prominently. In contrast, Fig. 1b depicts a joyful and playful tone characteristic of modern MNRs. It features terms like “Smiling (阿弥陀福)" and “Really fun (真好玩)", along with children’s activities such as “Hide and seek (捉迷藏)" and “Flying kites (放风筝)".

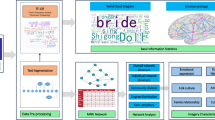

Overall framework

Figure 2 illustrates the architecture of our research on network analysis and sentiment classification of MNRs using the Joint-GraphSAGE method. The framework begins with dataset preprocessing, followed by text transformation using TF-IDF and Doc2Vec to create a combined vector representation, which is then used to build an MNR network. We perform network analysis based on the complex network theory to uncover the imagery of MNRs. Next, we propose a GNN model-Joint-GraphSAGE-for sentiment classification. This model leverages its ability to capture complex relationships and semantic nuances within the MNRs, thereby improving the accuracy of sentiment classification. We also compare our model with classical sentiment classification techniques, including SVM, LR, CNN, GCN, LSTM, Bi-LSTM, and GraphSAGE.

Data preparation

We outline a tailored processing pipeline for lyrics of MNRs that addresses the specific characteristics of the text, which mixes written Chinese (both simplified and traditional) with written Hokkien (a written form of the Minnan dialect) as follows.

(1) Conversion to simplified Chinese: convert all lyric texts into simplified Chinese to standardize the MNRs dataset.

(2) Removal of irrelevant characters: remove irrelevant characters such as special characters and punctuation that do not contribute to understanding the meaning of the lyrics.

(3) Custom tokenization: split the lyric texts into discrete tokens by a constructed Minnan-Jieba dictionary. Due to the limitation of Jieba segmentation for non-Chinese texts, the MNR lyrics segmentation will yield inaccurate results. Thus, we enrich the Jieba lexicon with a Minnan dialect dictionary to create an integrated Minnan-Jieba dictionary.

Calculation of lyric similarity

To quantitatively assess the similarity between two nursery rhymes, it is essential to convert the lyrical content of each rhyme into a numerical representation. We extract textual features by exploiting the strengths of two prevalent natural language processing techniques, TF-IDF and Doc2Vec. Specifically, TF-IDF is a statistics-based method that identifies keywords by calculating term frequency and inverse document frequency. This effectively amplifies unique and distinctive words in each nursery rhyme, reduces the weight of common words, and generates vector representations based on word frequency statistics. However, TF-IDF is limited to capturing statistical features and fails to account for semantic information and sequential context. In contrast, Doc2Vec, as a document-level neural embedding technique, directly learns vector representations of entire nursery rhymes. Unlike simple aggregation of word embeddings, this method preserves sequential context through paragraph-token training, thereby capturing semantic patterns inherent in structured short texts like MNRs. In our implementation, each nursery rhyme undergoes parallel processing: TF-IDF vectors are used to retain lexical frequency distributions, while Doc2Vec embeddings capture contextual semantic patterns. The TF-IDF and Doc2Vec vectors for each rhyme are then concatenated to form hybrid feature vectors, enabling a more comprehensive representation of the characteristics of nursery rhymes.

According to the obtained numerical representations of each nursery rhyme’s lyrics, we can then compute the similarity degree between any two nursery rhymes using the cosine similarity measure. For any two nursery rhymes, i and j, the cosine similarity score pij is defined by Eq. (1). The Aik in Eq. (1) is for the k-th element of the numerical feature vector for nursery rhyme i, the Bjk for the k-th element of the numerical feature vector for nursery rhyme j.

The pij is in the range of [−1, 1]. A similarity value of 1 indicates perfect similarity of two nursery rhymes, 0 indicates no similarity, and −1 indicates complete divergence.

Network construction

In the MNR network, each node represents a distinct nursery rhyme. According to the obtained cosine similarity in section “Calculation of lyric similarity”, the link between nursery rhyme nodes is determined by the Eq. (2). Specifically, a link connecting two rhymes i and j is established if the cosine similarity exceeds or equals a predefined threshold θ, and the similarity value is the weight of this link. Otherwise, no edges are formed. Since edges between connecting nodes are undirected, this construction process yields an undirected MNR network with the weighted adjacency matrix P.

Joint-GraphSAGE-based model

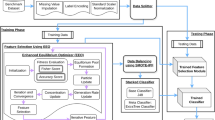

As shown in Fig. 3, the Joint-GraphSAGE model framework integrates both uniform and weighted sampling strategies across two convolutional layers to enhance node representation learning. In Convolution Layer 1, features are aggregated using a joint sampling strategy, which combines uniform sampling (random neighbor selection) and weighted sampling (selection based on edge weights) in the neighbor sampling process. Following a ReLU activation, Convolution Layer 2 further refines the features using the same joint sampling strategy. The output layer combines the node-level features from different layers, capturing comprehensive and informative node representations by leveraging node diversity and node importance within the graph.

Joint sampling strategy

In the original GraphSAGE framework, the sampling strategy is designed to uniformly select a fixed number of neighbors for each node. Under this strategy, each sampled neighbor contributes equally to the aggregated feature, regardless of the potential differences in the importance between the node and its neighbors. For the weighted MNR network constructed in this study, the importance of node neighbors and their influence on the representation of nodes are different. Therefore, a weighted sampling is designed to consider the link weight of the MNR network. For the weighted sampling strategy, neighboring nodes with higher edge weights are more likely to be sampled, while those with lower weights have a reduced chance of selection. Such a strategy inherently prioritizes more influential nodes during the representation learning process.

To balance the diversity and importance of neighbor selection in the MNR network, we consequently introduce a joint sampling strategy that combines both uniform and weighted sampling in the Joint-GraphSAGE model. As illustrated in Fig. 4, a probabilistic mechanism is devised to determine the sampling approach for each node. Specifically, a biased coin flip is conducted independently for every node, with a probability of α for a heads outcome. If heads, weighted sampling is employed; otherwise, uniform sampling is adopted. In Fig. 4, red nodes symbolize neighbors selected via uniform sampling, while pink nodes represent those chosen through weighted sampling. Specifically, when α is small, nodes are more likely to use uniform sampling; when α is large, nodes are more likely to use weighted sampling. It is essential to highlight that the proposed joint sampling strategy degenerates to pure weighted sampling for α = 1 and to pure uniform sampling for α = 0.

Embedding generation

For the given node v, its feature representation \({h}_{v}^{k}\) at layer k is obtained by concatenating the aggregated features \({h}_{{N}_{(v)}}^{k}\) from its neighbors N(v) with its previous layer features \({h}_{v}^{k-1}\). Here, the N(v) represents the set of nodes directly connected to the neighborhood of node v in the constructed MNR network. The initial feature of node v is obtained from the hybrid feature vector corresponding to its associated nursery rhyme. As defined in Eq. (3), CONCAT(,) is the concatenation operation. Then the concatenated output is subsequently fed into a fully connected layer with a nonlinear activation function σ. After passing through K iterations of embedding updates, the final representation \({h}_{v}^{k}\) of node v is achieved. For convenience, we denote this final representation as zv, which is equivalent to \({h}_{v}^{k}\).

The neighboring feature vector \({h}_{{N}_{(v)}}^{k}\) at layer k is computed by applying the aggregation function AGGREGATEk(,) to the feature representations \({h}_{u}^{k-1}\) of all neighboring nodes of node v from the previous layer. As shown in Eq. (4), AGGREGATEk(,) combines these neighboring features into a single aggregated vector for node v at layer k. This aggregation function is trainable and learned from the MNRs, with common methods such as element-wise mean and max-pooling operations.

Loss function

By iteratively performing sampling and aggregation procedures across its layers, the Joint-GraphSAGE model updates the feature representations of the nodes. This iterative process enables the model to encapsulate the intricacies of neighborhood connections and the relative importance of each link, leading to more expressive node representations. We employ supervised learning to train the Joint-GraphSAGE on the labeled MNRs. During the training phase, we utilize the cross-entropy loss, formalized in Eq. (5), for the sentiment classification of MNRs.

The Eq. (5) consists of two terms: The first term \(-\frac{1}{V}\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{v = 1}^{V}\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{c = 1}^{C}{y}_{vc}log\widehat{y}^{{\prime} }_{vc}\) quantifies the discrepancy between the actual labels and the predicted labels for node v. This term effectively measures the predictive accuracy of the model. The second term \(\lambda {\sum }_{\theta }{\left\Vert \theta \right\Vert }^{2}\) is the regularization loss over the network parameters, reducing the risk of overfitting. In Eq. (5), V denotes the number of labeled nodes in the training set, yvc represents the true labels of nodes for node v in the sentiment category c. The \(\widehat{y}^{{\prime} }_{vc}\) denotes the predicted label for node v, as inferred by the model.

The predicted label \(\widehat{y}^{{\prime} }_{vc}\) in Eq. (5), is computed through the softmax function at the final layer of the Joint-GraphSAGE. In Eq. (6), zvc represents the raw logit of node v with respect to the sentiment category c. The softmax normalizes these logits across all categories to produce a probability distribution, which reflects the model’s confidence in the prediction of each emotion category within the MNRs dataset.

Evaluation metrics

Aligning with established evaluation conventions, we adopt the accuracy (7) and F1 score (8) for systematic quantification of model performance, ensuring comparability with state-of-the-art approaches.

In Eqs. (7 and 8), TP represents the count of true positives, FP represents the count of false positives, FN represents the count of false negatives, and TN represents the count of true negatives.

Results

Overall network analysis of the MNR network

In the analysis of the MNR network, we use complex network metrics to reveal the characteristics of the cultural imagery of MNRs. Specifically, the overall network topology reflects the cultural dynamics of the MNRs, while the centrality measurements of the nodes demonstrate the distribution of significant imagery elements. This network-based imagery analysis approach enables us to understand and interpret the rich cultural connotations carried by MNRs from a data-driven perspective.

We use social network analysis to calculate the overall characteristics of traditional and modern MNR networks. As illustrated in Table 2, the traditional MNR network comprises 617 nodes and 169,187 edges, resulting in an average degree of 548.42 and a network density of 0.89. In contrast, the modern MNR network consists of 289 nodes and 6413 edges, yielding a significantly lower average degree of 44.38 and a network density of 0.15. These metrics indicate a high level of connectivity in the traditional MNR network, suggesting that each MNR is interlinked with a substantial proportion of other MNRs, thereby reflecting a significant degree of cultural homogeneity within the MNRs corpus. Conversely, the modern MNR network shows reduced connectivity, reflecting a more fragmented structure and possibly a more diverse or evolving cultural narrative.

Figure 5 demonstrates the degree distribution of two networks. The traditional MNR network (Fig. 5a) is characterized by a high prevalence of nodes with high degrees, indicating a dense connectivity and prominent hub nodes in the traditional MNR network. However, the modern MNR network (Fig. 5b) shows a power-law distribution with a majority of nodes having very low degrees.

Node centrality analysis of the MNR network

We quantitatively evaluate the role of an MNR by calculating the node centrality of MNR networks. Tables 3 and 4 show nodes with top-10 degree centrality, closeness centrality, betweenness centrality, and eigenvector centrality.

In the traditional MNR network, the top 10 nodes measured by degree and closeness centrality are the same. Additionally, the eigenvector centrality produces similar top-10 rankings. Specifically, the rhymes “Identifying Herbs (药仔歌)", “Chinese Flute (孔对孔)", “Huan-a Fangdidu (番仔番嘀嘟)" exhibit high centrality values across degree, betweenness, closeness, and eigenvector measures as shown in Table 3. The rhymes “Identifying Herbs (药仔歌)" and “Chinese Flute (孔对孔)" are Number Songs, which are frequently found in MNRs to teach children numbers. The term “Huan-a (番仔)" in the “Huan-a Fangdidu(番仔番嘀嘟)" is used by Han Chinese to describe foreigners (specifically, meaning Malaysians in our data set). The “Huan-a Fangdidu(番仔番嘀嘟)" in MNRs is often used to describe the living habits of overseas Minnan people. In addition, in the Minnan region, Huan-a buildings (番仔楼) are a type of residential architecture that blends Chinese and Western styles. These buildings are typically constructed by overseas Chinese who either return to their hometowns or remit funds for their construction. The high ranking of these three rhymes not only reflects the broad relevance of their lyrics to other rhymes but also underscores their importance and prevalence in the sociocultural lexicon of traditional MNRs. Rhymes “Kite (鹞)", “Eating Noodles (食线)", and “Exorcism Chant (收惊歌)" also have very high centrality values. They include lyrics such as “...The kite flies up the mountain, the child will become an official in the future. The kite flies high and hangs in the air; the child will become a top scholar in the future (鹞飞上山, 婴仔日后会做官. 鹞飞悬悬, 婴仔日后中状元)..." and “After cooking noodles with oyster omelette, the old man eat a bowl of the noodle, and the old woman eat a plate of the noodle (蚵仔辇,煮面线,公仔食一碗,婆仔食一碟)," to describe the unique food culture and blessing custom of the Minnan region. It should be noted that the betweenness centrality yields significantly different ranking results compared to the other three measures. This metric highlights rhymes with a distinct thematic focus. For example, the rhyme “Rice Pounding Maiden (舂米姑仔)" employs personification to depict labor scenes, while “First Birthday Celebration Day (度晬天)" and “Hair-combing Ritual Ballad II (上头谣(二))" describe the blessings and ritual customs. Rhymes “Pearl as Treasure Cup (珍珠做宝斗)" and “Stones on The Niche (顶龛石)" center on guessing games for children, and “Spies Scattered to Arrest People (暗牌四散舂)" is a political song records people’s work and life from the British colonial period (in the 1850s).

As shown in Table 4, the centrality analysis of the modern MNR network reveals similar top-10 rankings across degree centrality, closeness centrality, and eigenvector centrality. A core group of nursery rhymes, including “Goddess Matsu Spread Benevolence Everywhere (妈祖仁爱满四海),” “Bees With Colorful Bellies II (蜜蜂花仔肚(二)),” “It is a pity that Good Flower Was Stuck in Cow Dung (无采好花插牛屎),” “Rolling the Iron Hoop (遨铁环),” “Pushing Hands (推手),” “Cockfighting Game (咬鸡),” and “Compatriots on Both Sides of the Taiwan Strait Share the Same Root (两岸同胞同根源),” consistently rank high in degree, closeness, and eigenvector centrality measures, indicating their central role in the modern MNR network. Similar to the imagery expressed in Talbe 4, these rhymes also reflect the religious devotion of Minnan people, the educational values of MNRs, and social themes prevalent in the Minnan region. For instance, “Goddess Matsu Spread Benevolence Everywhere (妈祖仁爱满四海)" highlights the religious devotion to the Goddess Mazu, while rhymes “Bees With Colorful Bellies II (蜜蜂花仔肚(二)),” “Rolling the Iron Hoop (遨铁环),” “Pushing Hands (推手),” and “Cockfighting Game (咬鸡)” emphasize children’s enlightenment puzzles and activities. Notably, the inclusion of “Compatriots on Both Sides of the Taiwan Strait Share the Same Root (两岸同胞同根源)” and “One Should Be an Honest Person (做人着做老实人)” is particularly significant, which exemplifies the social values embedded within the nursery rhymes. Apart from the three rhymes–"Goddess Matsu Spread Benevolence Everywhere (妈祖仁爱满四海),” “Bees With Colorful Bellies II (蜜蜂花仔肚(二)),” “It is a pity that Good Flower Was Stuck in Cow Dung (无采好花插牛屎),”—appear in the top-10 rankings of degree, closeness, and eigenvector centrality, some other nursery rhymes in Table 4 exhibit notably high betweenness centrality. For example, nursery rhymes such as “Millet Festival (栗祭)” and “The Mountain Dressed in Golden Silk (满山罩金纱)” celebrate the festive and joyful aspects of the harvest season. “Be Filial to Parents with Genuine Feelings (孝敬父母着真情)” promotes Confucian values of filial piety, while “Waiting to Return Soon (等要早日转咋兜),” “Taiwan Produces Sweet Rice Cakes (台湾出甜粿),” and “Big Cheap and Clumsy (大抠呆)” highlight regional culinary traditions. “Thundershower Kept falling (西北雨直直落)” illustrates the reliance on traditional deities for guidance during challenging times, illustrating the enduring influence of local religious practices. These rhymes indicate their bridging roles across different themes within the modern MNR network.

To conclude, the high centrality rankings of these nursery rhymes underscore their significant roles in both traditional and modern Minnan cultural contexts. These rhymes reveal a deep connection to various aspects of Minnan culture, including religious devotion, food culture, folk customs, social critique, and children’s education. The prominence of these aspects reflects their enduring influence and the way they serve as a medium for transmitting cultural values and social concerns of the Minnan community. The presence of similar imagery in traditional and modern MNRs suggests their continued relevance and adaptability in addressing the changing dynamics of the Minnan region.

Experiment settings for sentiment prediction of Joint-GraphSAGE

For the proposed Joint-GraphSAGE, the experimental datasets are partitioned into training and test sets using various split ratios ranging from 0.5:0.5 to 0.9:0.1. The deep learning framework used is PyTorch 1.10.0 in the experiments. Our dataset, code, and implementation details can be found at: https://github.com/MiyaWu/GNN-Sentiment-Classification-of-MNRs. For evaluating the performance of Joint-GraphSAGE, we employ several widely used machine learning, deep learning models, and GNN models as baselines, including SVM (support vector machine)34, LR (logistic regression)35, CNN36, LSTM37, Bi-LSTM (bidirectional long short-term memory)38, and GraphSAGE39. These models are selected due to their proven effectiveness in text classification tasks, particularly sentiment classification, thereby offering a robust benchmark for assessing the performance of the Joint-GraphSAGE model. Notably, the machine learning and deep learning models in this study operate solely on nodal feature vectors (i.e., the hybrid feature vectors derived from the integration of TF-IDF and Doc2Vec in section “Calculation of lyric similarity”), without considering the structural relationships within the network. The details of the selected baseline models are described as follows:

-

(1)

SVM34: SVM is a typical machine learning model that separates data points into distinct categories by identifying an optimal hyperplane. It employs structural risk minimization and kernel methods to handle both linear and nonlinear classification in high-dimensional space, making it effective for sentiment classification by learning the emotional similarity between words.

-

(2)

LR35: LR is a simple and efficient classification model used for binary or multiclass classification tasks. By converting text data into numerical features and applying the LR model, sentiment classification can be effectively performed.

-

(3)

CNN36: CNN is a powerful class of deep learning models widely used for various tasks in computer vision and natural language processing. CNN for sentiment classification involves transforming text into a numerical form that the network can analyze and then applying convolution and pooling operations to extract meaningful features and patterns in the text. This ultimately allows the network to classify the sentiment expressed in the text.

-

(4)

LSTM37: LSTM is a recurrent neural network designed to capture long-distance dependencies among words. In sentiment classification, LSTM processes text by retaining essential contextual information over long sequences, enabling the model to make accurate sentiment classification.

-

(5)

Bi-LSTM38: Bi-LSTM is an enhanced version of LSTM that captures both forward and backward dependencies. This bidirectional approach allows the model to capture intricate dependencies and relationships between words in text, making it highly effective for sentiment classification.

-

(6)

GraphSAGE39: GraphSAGE is a GNN that can be applied to sentiment classification by representing words as nodes in a graph and learning the emotional relationships between them. By employing uniform sampling and aggregating from neighboring nodes, GraphSAGE can uncover the latent emotional context of words to facilitate accurate sentiment classification.

Sentiment prediction evaluation with Joint-GraphSAGE

To evaluate model performance under different training data sets, we varied training-test split ratios from 0.5:0.5 to 0.9:0.1 for the sentiment classification task of MNRs. We compare the results of Joint-GraphSAGE with six baseline models. To ensure a robust evaluation of classification accuracy, we conduct ten repeated experiments for each model and report the average results from these experiments. The experimental results on traditional MNRs and modern MNRs are summarized in Tables 5–8, respectively.

For the traditional MNRs, as shown in Tables 5 and 7, the Joint-GraphSAGE consistently outperforms all other methods in both accuracy and F1 score across various training-test splits. The Joint-GraphSAGE achieves the highest accuracy rate of 91.46% with a 0.5:0.5 split, which is at least 38.23% higher than the accuracy rates of classical machine learning models and deep learning models. In particular, the graph-based model GraphSAGE also outperforms machine learning and deep learning models, achieving a peak accuracy of 89.21% at a 0.5:0.5 split. However, it is 2.25% lower than Joint-GraphSAGE. The results in Table 5 also show that machine learning models generally outperform deep learning models on the traditional MNRs. For example, SVM and LR achieve their highest accuracies of 50.00% and 53.23%, respectively, with a 0.8:0.2 split. In contrast, deep learning models such as LSTM and Bi-LSTM reach lower accuracies of 46.05% and 44.76%, respectively, at the same split. CNN performed the least favorably, attaining its highest accuracy of 44.44% at the 0.8:0.2 split. Similarly, Joint-GraphSAGE gets the highest F1 score of 91.36% with a 0.5:0.5 split. GraphSAGE again shows good performance with an F1 score of 88.98% at the same split, but it still lags behind the Joint-GraphSAGE by 2.38%. Comparatively, SVM and LR obtain F1 scores of 39.50% and 41.94%, respectively, with a 0.8:0.2 split. LSTM and Bi-LSTM achieve F1 scores of 41.86% and 41.94% with the same split. CNN performs the worst, with an F1 score of 38.68% at the 0.8:0.2 split.

In Tables 6 and 8, the accuracy of sentiment classification for modern MNRs is comparable to that observed in traditional MNRs. However, the F1 scores reveal a decline for modern MNRs compared to their traditional counterparts. In terms of classification accuracy, Joint-GraphSAGE significantly outperforms other methods in all split ratios, achieving the highest accuracy rate of 95.74% with a 0.7:0.3 split, which is significantly higher than other models. The GraphSAGE model follows closely with a peak accuracy of 92.68% at the same split, but is still about 3.06% lower than Joint-GraphSAGE. In contrast, the SVM and LR machine learning methods, as well as CNN, LSTM, and Bi-LSTM deep learning algorithms, exhibit relatively lower performance. Specifically, SVM and LR get the highest accuracy of 79.31% with the 0.8:0.2 and 0.9:0.1 splits. LSTM, CNN, and Bi-LSTM show relatively lower performance, with their highest accuracy values of 79.31%, 77.07%, and 73.10%, respectively. In particular, the accuracy performance in sentiment classification for modern MNRs is significantly higher compared to that of traditional MNRs. This improvement may be attributed to the lower semantic diversity and fewer lexical combinations present in modern MNRs, in contrast to the more complex semantic structures found in traditional MNRs. Regarding the F1 score, Table 8 shows that the Joint-GraphSAGE surpasses the five machine learning and deep learning baselines, namely SVM, LR, CNN, LSTM, and Bi-LSTM. Specifically, Joint-GraphSAGE reaches the highest F1 score of 89.44% at the split 0.6:0.4, which is at least 10.98% higher than the F1 scores of five baselines. GraphSAGE has the second-best performance in general, with its highest F1 score reaching 84.17%, which is 5.27% lower than that of Joint-GraphSAGE. When comparing the two graph-based models, Joint-GraphSAGE is 2.14% lower than GraphSAGE at the 0.8:0.2 split, potentially due to overfitting arising from its increased training samples.

In summary, the proposed Joint-GraphSAGE model exhibits superior performance in sentiment classification tasks for both traditional and modern MNRs compared to baseline machine learning and deep learning models, as well as the GraphSAGE model. These results underscore the importance of incorporating graph structure into sentiment classification for MNRs. By employing joint sampling and leveraging the graph structure of MNRs, the Joint-GraphSAGE model captures more comprehensive contextual representations that encompass both semantic content and inter-textual relationships, thereby enhancing predictive performance compared to GraphSAGE.

Parameter sensitivity analysis of Joint-GraphSAGE

In the Joint-GraphSAGE model, the α parameter plays a crucial role in the neighbor sampling process. As described in the section “Joint sampling strategy”, a lower α value emphasizes neighbor diversity but may neglect important nodes, while a higher α value focuses more on neighbors with large-weight links, potentially limiting the diversity of information obtained. The parameter α ranges from 0 to 1. It is noticeable that Joint-GraphSAGE draws back to the standard GraphSAGE when α = 0. When α = 1, Joint-GraphSAGE only considers important neighbors in the sampling process. For the traditional MNR network, as depicted in Table 9, the Joint-GraphSAGE demonstrates consistently high accuracy and F1 scores across different α values, albeit with minor fluctuations. Both accuracy and F1 score reach their peaks at α = 0.5, reaching values of 91.46% and 91.36%, respectively, as marked bold in Table 9. This suggests that the model effectively balances neighbor diversity and edge weight information at α = 0.5, leading to improved sentiment classification. Specifically, the performance of Joint-GraphSAGE exhibits a trend of initially increasing and then decreasing with the increase of α, which can be attributed to the role of α in balancing neighbor diversity and the selection of important neighbors. In comparison, the Joint-GraphSAGE displays a similar pattern on the modern MNR network. As illustrated in Table 9, the accuracy and F1 score increase gradually as α rises from 0 to 0.5, reaching a peak at α = 0.5 with 95.74% and 88.89%, respectively, as marked bold in Table 9. Then, further increases in α lead to a decreasing performance of Joint-GraphSAGE. The F1 score of Joint-GraphSAGE decreases to 79.28% at α = 1. It is worth noting that the performance of Joint-GraphSAGE on modern MNR datasets is more sensitive to variations in α compared to its performance on traditional MNR datasets. Specifically, the fluctuations of accuracy (and F1 score) is around 3% (and 9%), respectively, i.e., a maximum difference of 3% (and 9%) between the highest and lowest accuracy values (and F1 scores). These higher fluctuations in the modern MNR network can be caused by its lower density and degree (see Table 2 and Fig. 5) compared to the traditional MNR network, which renders Joint-GraphSAGE more sensitive to the neighbor sampling strategy affected by variations in α.

The threshold θ for network construction is also essential as it determines the MNR network’s structure and may impact the sentiment classification performance of Joint-GraphSAGE. As introduced in the section “Network construction”, a high threshold θ leads to a sparse network, which may make it challenging to capture semantic relationships between nursery rhymes. Conversely, a low threshold θ will generate a dense network, which may introduce noise and reduce model robustness. To investigate the effect of threshold θ on the performance of Joint-GraphSAGE in MNR sentiment classification, we examine the accuracy and F1 score of Joint-GraphSAGE under different threshold values in Fig. 6. As shown in Fig. 6a, the accuracy and the F1 score on the traditional MNR network reach their peak values (91.46% and 91.36%, respectively) at the threshold of 0.6, suggesting that the Joint-GraphSAGE model performs optimally at this specific threshold θ. The model’s performance exhibits relative stability within the θ range of 0.3–0.8, with accuracy and F1 scores fluctuating within 3% and 5%, respectively, and both metrics exceeding 87%. However, at θ = 0.9, a sharp decline in both accuracy (to 80.23%) and F1 score (to 81.93%) is observed, indicating that an overly sparse network, induced by an excessively high θ, negatively impacts the performance of Joint-GraphSAGE. Different from the results presented in Fig. 6a, the classification accuracy and F1 score of Joint-GraphSAGE on the modern MNR network exhibit greater instability with variations in the threshold θ. Specifically, as shown in Fig. 6b, the difference between the maximum accuracy (95.74% at θ = 0.8) and the minimum accuracy (87.34% at θ = 0.3) does not exceed 9% with varying threshold θ. In addition, the variation in F1 scores across different threshold values is more pronounced. It is noticeable that the F1 score is 67.12% at θ = 0.3 and increases to a peak value of 88.89% at θ = 0.8 in Fig. 6b. This significant difference may be attributed to the highly imbalanced semantic categories in the modern MNR dataset. As indicated in Table 1, the top five categories in modern MNRs constitute approximately 93.08% of the total sentiment categories. Consequently, when the network is highly dense with a small value of θ, the Joint-GraphSAGE model tends to exhibit a strong bias towards predicting the majority class. This bias results in reduced model performance.

Discussion

To advance the understanding of Minnan cultural heritage, this study uses MNRs as a case study and introduces a novel architecture for imagery analysis and sentiment classification. We first preprocessed and extracted textual features from both traditional and modern MNRs, constructing corresponding networks where the rhymes serve as nodes and co-occurrence relationships form the edges. Network analysis, based on the complex network theory, was then employed to uncover the imagery of MNRs. Subsequently, we developed a GNN model, Joint-GraphSAGE, to predict the sentiment of MNRs.

The imagery analysis conducted in this study, encompassing word cloud diagrams, overall network analysis, and node centrality measures, yielded significant insights into the thematic content and structural characteristics of MNR networks. The identification of key nursery rhymes in both traditional and modern MNRs underscored deep regional culture, such as religious devotion, food culture, folk customs, social critique, and educational values, embedded within these rhymes. Our proposed Joint-GraphSAGE model outperformed commonly used machine learning and deep learning models, as well as GraphSAGE in sentiment classification. Specifically, Joint-GraphSAGE achieved the highest accuracy rate (or F1 score) of 91.46% (or 91.36%) on the traditional MNR network, significantly surpassing the performance of baseline models. Similarly, Joint-GraphSAGE exhibited the highest prediction accuracy (95.74%) on the modern MNR network, maintaining a good F1 score (88.89%) despite a high imbalance among semantic categories. These experiments highlighted that capturing intricate relationships and semantic nuances, along with integrating uniform and weighted sampling strategies across convolutional layers, can significantly improve the sentiment classification performance of the Joint-GraphSAGE model.

This exploration of sentiment prediction in MNRs using GNNs provides promising avenues for future research. One such direction involves integrating multimodal data by combining lyrical content with vocal audio, which is expected to significantly enhance sentiment prediction accuracy. Expanding the scope of this study to include a broader range of Minnan songs, rather than focusing solely on nursery rhymes, is another interesting direction, as it would yield more robust and generalizable findings in sentiment prediction and offer deeper insights into regional variations in musical forms. Lastly, constructing a large-scale, comprehensive multimodal knowledge graph of Minnan songs will provide an integrated framework for analyzing, preserving, and expanding knowledge about Minnan’s musical heritage. Such future research will also enhance sentiment analysis, uncover hidden patterns, promote interdisciplinary studies, and support cultural preservation.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Code availability

The implementation code can be found at https://github.com/MiyaWu/GNN-Sentiment-Classification-of-MNRs.

References

Heritage, U. I. C. Texts of the convention for the safeguarding of the intangible cultural heritage. In Tillgänglig på Internet: https://ich. unesco. org/en/convention [hämtad Mars 2, 2020] J White, W. et al.(2018) Tabletop role-playing games. I Deterding, S. Zagal, J.(red.) Role-Playing Game Studies: Transmedia Foundations Routledge Taylor & Francis Group Østbye, H. et al. (2003) (Metodbok för Medievetenskap, Malmö, 2003).

Hui, L. The multi-cultural value of Minnan nursery rhymes and their contemporary transmission. Fujian Forum (Humanities and Social Sciences Edition) 125–128 (Universe Scientific Publishing, 2012).

Blake, J. Unesco’s 2003 convention on intangible cultural heritage. Intangible Heritage 45 (Routledge, 2008).

Chen, W. A Grammar of Southern Min: The Hui’an Dialect. (Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin, 2020).

Yanping, D. The linguistic excavation value of Minnan nursery rhymes. New Course (Comprehensive Edition) 10–11 (2019).

Wang, M. A new perspective on the inheritance of minnan nursery rhymes from the perspective of intangible cultural heritage. Contemp. Lit. Art. 6, 204–206 (2015).

Minnan Nursery Rhymes (accessed 10 December 2023; https://xiamen.chinadaily.com.cn/2019-05/06/c_346992.html (2019).

White, C. Waves of influence across the south seas: mutual support between protestants in minnan and southeast asia. Ching Feng 11, 29–54 (2012).

Junyu, R. The cultural value and transmission of minnan nursery rhymes in the context of intangible cultural heritage. J. Shenyang Norm. Univ. 37, 172–174 (2013).

Miao, W. Analysis of the contemporary cultural and educational value of minnan nursery rhymes. Literature & Art Criticism 4 (Universe Scientific Publishing, 2017).

Shunmei, L. & Zahari, Z. A. The design and development of cultural and creative products from the perspective of digital media-taking intangible cultural heritage of nursery rhymes in minnan dialect as an example. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 6, 287–298 (2022).

Network CICH. List of Representative Items of National Intangible Cultural Heritage. https://www.ihchina.cn/project.html (2008).

Thwaites, H. Digital heritage: What happens when we digitize everything? Visual Heritage in the Digital Age 327–348 (Springer, London, 2013).

Newell, J. Old objects, new media: Historical collections, digitization and affect. J. Mater. Cult. 17, 287–306 (2012).

Yasser, A., Clawson, K., Bowerman, C., Lévêque, M. et al. Saving cultural heritage with digital make-believe: machine learning and digital techniques to the rescue. In HCI’17 Proc 31st British Computer Society Human Computer Interaction Conference, Vol. 97, 1–5 (ACM, 2017).

Chen, Z., Huang, J., Dai, H. & Liu, J. Development route analysis of intangible cultural heritage industry of china based on data mining. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series, Vol. 1848, 012040 (IOP Publishing, 2021).

Dou, J., Qin, J., Jin, Z. & Li, Z. Knowledge graph based on domain ontology and natural language processing technology for chinese intangible cultural heritage. J. Vis. Lang. Comput. 48, 19–28 (2018).

Pang, B. & Lee, L. et al. Opinion mining and sentiment analysis. Found. Trends® Inf. Retr. 2, 1–135 (2008).

Hemmatian, F. & Sohrabi, M. K. A survey on classification techniques for opinion mining and sentiment analysis. Artif. Intell. Rev. 52, 1495–1545 (2019).

Sadia, A., Khan, F. & Bashir, F. An overview of lexicon-based approach for sentiment analysis. In 2018 3rd International Electrical Engineering Conference 1–6 (IEEC, 2018).

Patel, S. N. & Choksi, M. J. B. A survey of sentiment classification techniques. J. Res. 3, 2347–3878 (2015).

Zhang, H., Gan, W. & Jiang, B. Machine learning and lexicon based methods for sentiment classification: A survey. In 2014 11th web information system and application conference 262–265 (IEEE, 2014).

Zhang, L., Wang, S. & Liu, B. Deep learning for sentiment analysis: a survey. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 8, e1253 (2018).

Do, H. H., Prasad, P., Maag, A. & Alsadoon, A. Deep learning for aspect-based sentiment analysis: a comparative review. Expert Syst. Appl. 118, 272–299 (2019).

Ayetiran, E. F. Attention-based aspect sentiment classification using enhanced learning through cnn-bilstm networks. Knowl.-Based Syst. 252, 109409 (2022).

Kipf, T. N. & Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR, 2017).

Velickovic, P. et al. Graph attention networks. stat 1050, 10–48550 (2017).

Xiao, L. et al. Targeted sentiment classification based on attentional encoding and graph convolutional networks. Appl. Sci. 10, 957 (2020).

Li, Y. & Li, N. Sentiment analysis of Weibo comments based on graph neural network. IEEE Access 10, 23497–23510 (2022).

Lu, G., Li, J. & Wei, J. Aspect sentiment analysis with heterogeneous graph neural networks. Inf. Process. Manag. 59, 102953 (2022).

Wang, M. & Hu, G. A novel method for twitter sentiment analysis based on attentional-graph neural network. Information 11, 92 (2020).

Phan, H. T., Nguyen, N. T. & Hwang, D. Aspect-level sentiment analysis: a survey of graph convolutional network methods. Inf. Fusion 91, 149–172 (2023).

Jin, Z., Tao, M., Zhao, X. & Hu, Y. Social media sentiment analysis based on dependency graph and co-occurrence graph. Cogn. Comput. 14, 1039–1054 (2022).

Mullen, T. & Collier, N. Sentiment analysis using support vector machines with diverse information sources. In Proc. 2004 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing 412–418 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Barcelona, 2004).

Prabhat, A. & Khullar, V. Sentiment classification on big data using naiuml;ve bayes and logistic regression. In 2017 International Conference on Computer Communication and Informatics (ICCCI), 1–5 (IEEE, 2017).

Dos Santos, C. & Gatti, M. Deep convolutional neural networks for sentiment analysis of short texts. In Proc COLING 2014, the 25th International Conference on Computational Linguistics: Technical Papers 69–78 (Dublin City University and Association for Computational Linguistics, Dublin, 2014).

Li, D. & Qian, J. Text sentiment analysis based on long short-term memory. In 2016 First IEEE International Conference on Computer Communication and the Internet (ICCCI) 471–475 (IEEE, 2016).

Zhang, K., Song, W., Liu, L., Zhao, X. & Du, C. Bidirectional long short-term memory for sentiment analysis of chinese product reviews. In 2019 IEEE 9th International Conference on Electronics Information and Emergency Communication (ICEIEC) 1–4 (IEEE, 2019).

Hamilton, W., Ying, Z. & Leskovec, J. Inductive representation learning on large graphs. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS, Long Beach, 2017).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 62106092 and 22074058), the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (No. 2022J01916), the Natural Science Foundation of the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China (No. 22KJB520023), the Foundation of State Key Lab. for Novel Software Technology (No. KFKT2022B35), the National Social Science Found of China (No. 20FZWB038), the Key Lab of Intelligent Optimization and Information Processing, Minnan Normal University (No. ZNYH202004), and the Graduate Education Reform Project of Minnan Normal University (No. YJG202305). The authors wish to particularly acknowledge Yuena Wang and Deyi Yu for their valuable suggestions on understanding the proverbs of the Minnan language.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: H.W. and S.L. Methodology: H.W. and Q.W. Validation: B.L., F.Y., and Z.X. Result analysis: H.W., Q.W., and Z.X. Investigation: B.L., F.Y., and Z.X. Data collection and labeling: Q.W. and H.W. Data curation: Z.X. and H.W. Writing—original draft preparation: Q.W. and H.W. Writing—review and editing: B.L., F.Y. and Z.X. Visualization: Q.W. and H.W. Reviewing, language and editing: B.L., F.Y. and Z.X. Project administration: S.L. Funding acquisition: H.W., Z.X. and S.L.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, H., Wu, Q., Lin, B. et al. Network analysis and sentiment classification of Minnan nursery rhymes. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 172 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01773-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01773-0