Abstract

The architectural texture of traditional villages reflects regional culture and is vital for sustainable conservation and renewal. However, for culturally diverse villages, current methods often lack integration of multi-dimensional evaluation and fusion of traditional and modern techniques, limiting data efficiency and analytical rigor. This study proposes a framework combining UAV remote sensing, deep learning (optimized Mask R-CNN), morphological indices, and statistical analysis. Applied to 27 traditional villages in Beijing, results show: (1) the method enables fast, accurate extraction of architectural texture with minimal manual input; (2) villages show heterogeneity in scale, proportion, and orientation, while patterns and boundaries remain stable; (3) texture features are influenced by geography, culture, history, economy, and construction methods; (4) indicators like settlement size and building proportion correlate strongly with other variables, offering insights for spatial planning. This interdisciplinary approach supports scientific evaluation and offers a digital foundation for preserving and optimizing traditional village environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traditional villages are vital witnesses of human civilization, carrying significant historical, artistic, and scientific value. Over centuries of social and cultural evolution across diverse geographical environments, these settlements have developed unique landscape characteristics—such as architectural styles, spatial patterns, and boundary forms—that reflect local culture and ethnic identity1,2. However, rapid global urbanization has triggered widespread threats to vernacular environments, including the expansion of village boundaries, destruction of traditional buildings, disordered spatial layouts, disproportionate architectural scales, and blurred settlement edges. These issues pose serious challenges to the preservation of local cultural heritage3.

To address this, China’s Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development has introduced the Evaluation and Identification Index System for Traditional Villages (Trial)4, which highlights architectural texture as a key indicator of the overall physical character of village architecture. It plays a crucial role in understanding settlement development patterns and guiding landscape conservation5. Therefore, there is an urgent need for a universal and transferable evaluation framework capable of identifying and assessing architectural textures. Such a system would support intelligent analysis, protection, and sustainable development of traditional villages across multicultural contexts.

Since the early geographic analysis of urban layouts by Conzen, quantitative morphological indices have evolved into a cross-culturally applicable method6. Based on mathematical and statistical principles of spatial form, these indices offer notable advantages in terms of practicality, flexibility, and operability. They have been widely applied in studies of architectural texture from various perspectives.

For example, several studies have demonstrated the feasibility of using shape indices to analyze spatial disorder, diversity, and complexity7,8,9. Other applications include assessments of settlement boundaries, road network patterns, building orientation indices10, patch area, fractal dimensions, and settlement scale indices11, as well as broader morphological features, spatial structures, and integrated building orientation metrics12. Some studies further combine morphological indicators with space syntax13, or utilize indices such as ratio, boundary definition, saturation, and building density14.

These methods have been employed in diverse contexts, including China10,13,15, Vietnam16, and Indonesia17, contributing to the scientific rigor of traditional village morphology studies and demonstrating the adaptability and universality of morphological index approaches across different regions.

Although morphological index methods have been widely applied, they still fall short in advancing a systematic architectural texture index framework and revealing deeper underlying mechanisms. The architectural texture of traditional Chinese villages is highly specific, shaped by geographical location, cultural context, and social relationships. Notably, mountain villages account for more than half of the nationally protected traditional villages, exhibiting spatial layouts that are distinctly adapted to topographic conditions, in contrast to those in plains regions18.

In different regions, building orientation is influenced to varying degrees by the Confucian cosmological worldview, reflecting certain spatial organization patterns and directional logic19. Furthermore, the layout and clustering of buildings are often reinforced by kinship ties, resulting in unique courtyard group formations20. These complex, multi-dimensional texture features require a more customized and context-sensitive evaluation framework.

Current research tends to focus on a single or limited set of architectural texture dimensions, lacking a comprehensive and systematic exploration of architectural texture indicators. Most studies emphasize either comparative descriptions of texture features10,12,14 or their relationships with elements such as transportation, natural environment, and local customs7,8,15, while the latent structural patterns across multiple dimensions remain understudied. This limits the ability to reveal the developmental logic and spatial evolution of traditional village forms.

Therefore, under the premise of high-quality and refined spatial management, future research should emphasize the construction of a multidimensional index system that integrates features such as settlement boundary morphology, building distribution patterns, orientation, settlement scale, and architectural proportions.

It is worth noting that the complex geographical environments of traditional villages often make field surveys time-consuming and labor-intensive. In earlier periods with limited technological capacity, large-scale and rapid investigation or quantitative evaluation of architectural textures in traditional villages was extremely difficult21. With the advancement of digitalization, informatization, and artificial intelligence, deep learning and remote sensing technologies have significantly improved the efficiency of data acquisition and processing in heritage conservation, bringing new momentum to the study of traditional village architectural textures22.

Due to resolution limitations, open-access satellite imagery is mostly suitable for detecting sparsely distributed buildings17,23,24 or settlement patches that exhibit clear contrast with their surroundings25. However, it remains inadequate for extracting detailed texture information from traditional villages, which typically feature multi-type, multi-scale, and multi-temporal architectural forms. In contrast, drone-based remote sensing has been widely adopted in the heritage field for its low cost, high operability, and noninvasive nature26. When enhanced with super-resolution reconstruction, UAV imagery can clearly capture the complex built environments of traditional villages27,28. Combined with deep learning models such as Mask R-CNN and HRNet, this approach enables high-precision extraction of architectural texture features in Chinese traditional villages, including automated identification of building types, locations, and boundaries29,30,31.

While integrated approaches combining remote sensing, Earth observation, and morphological index analysis have been successfully applied in urban studies32,33, their application to the evaluation of architectural texture in traditional villages remains largely unexplored. Whether these methods can fully leverage their advantages—namely high accuracy, scientific rigor, and efficiency—still requires further investigation.

This study integrates deep learning, UAV remote sensing, and traditional morphological indices to establish a technical framework for evaluating the architectural texture of traditional villages, addressing common challenges in vernacular cultural heritage preservation. First, deep learning models are combined with drone imagery to efficiently extract information on building types, boundaries, and spatial distribution. Based on this, a correlation analysis of multidimensional architectural texture indicators is conducted, demonstrating how culturally meaningful texture metrics can be embedded within a generalized analytical framework. The study further reveals common features, spatial anomalies, and underlying structural relationships in the architectural textures of traditional villages in Beijing. Using traditional villages in Beijing as a case study, the proposed framework proves to be both practical and transferable, offering valuable insights for international heritage conservation efforts facing similar challenges.

Methods

The study aims to provide a scientific, efficient, and comprehensive assessment of the architectural texture of traditional villages. It develops an integrated technical approach that combines deep learning, UAV remote sensing, the morphology index method, and correlation coefficient analysis, as shown in Fig. 1. In data acquisition and processing, drones capture and reconstruct high-resolution images. For deep learning, the enhanced Mask R-CNN model is employed to address the complex features of the built environment in traditional villages. The morphology index method classifies building types and establishes a quantitative evaluation system for architectural texture. In characterizing architectural texture, descriptive statistics, histogram analysis, and correlation coefficient analysis are used to examine the distribution, standard features, and intrinsic correlations of architectural texture. The study also investigates the underlying causes of the architectural texture and proposes recommendations for future optimization and control.

UAV remote sensing

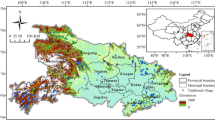

Beijing has a rich cultural heritage of traditional villages. Since the 2012 survey, 26 national-level traditional villages have been identified, each with significant historical and cultural backgrounds, including Red Culture, Great Wall Culture, and Ancient Road Culture. In line with the Beijing Urban Overall Plan (2016–2035), the city has also selected 44 municipal-level traditional villages, with a focus on those that, while not nationally recognized, hold considerable value for preservation. Additionally, Beijing is home to numerous historical villages with deep cultural significance, such as the fortress settlements at the base of the Ming Great Wall in Miyun District. These villages, with their wealth of traditional buildings and well-preserved settlement patterns, offer comparable research value to the existing traditional villages. This study focuses on 27 villages, including 19 national-level traditional villages, 3 municipal-level traditional villages, and 5 historical villages (Fig. 2).

Study area, Note: 1. Baimaguan Village; 2. Chaoguan Village; 3. Dongguan Village; 4. Dongshiguyan Village; 5. Gubeikou Village; 6. Heshi Village; 7. Jijiaying Village; 8. Jieshi Village; 9. Lingshui Village; 10. Malan Village; 11. Weizishui Village; 12. Xihulin Village; 13. Xiaokou Village; 14. Yanhecheng Village; 15. Yaoqiaoyu Village; 16. Xiaoying Village; 17. Xituogu Village; 18. Fengjiayu Village; 19. Qianjuntai Village; 20. Huanglingxi Village; 21. Shuiyu Village; 22. Baoshui Village; 23. Liugshui Village; 24. Nanjiao Village; 25. Shangyu Village; 26. Heilongguan Village; 27. Cuandixia Village.

Given the complex traffic conditions and geographic features of traditional villages in Beijing, this study employs the DJI M300RTK UAV to capture low-altitude remote sensing images. To minimize the impact of solar radiation, wind speed, and other environmental factors on data quality, data collection was conducted under sunny and breezy weather conditions. A detailed flight plan was developed, incorporating flight altitude, speed, overlap rate, and return altitude, as outlined in Table 1. The raw image data were then reconstructed with super-resolution using Context Capture software, enabling clear visualization of building morphology, materials, and colors (Fig. 3). This approach offers significant advantages over open-source remote sensing images, effectively overcoming the resolution limitations of traditional high-resolution sources.

Deep learning model

Given the multi-scale, multi-type, and multi-temporal architectural distribution in traditional villages, this study employs an enhanced Mask R-CNN instance segmentation model29, derived from the original Mask R-CNN34 with superior architecture and fitting performance. The model replaces the traditional feature pyramid with the path aggregate feature pyramid network (PAFPN)35, which leverages precise localization signals from the bottom layer, shortening the information path, and enhancing the contextual relationships between multi-layer features. This modification improves the model’s ability to handle complex environments. Additionally, the inclusion of the atlas space pyramid pool (ASPP)36 module captures multi-scale information, further enhancing the model’s detection and recognition capabilities in complex settings. To address data scarcity, the study incorporates transfer learning and data augmentation strategies during the pre-training phase.

In practical application, tasks such as building classification, data labeling, training, evaluation, and morphological optimization are carried out sequentially (Fig. 4). First, the study catalogs the roof forms, materials, and colors of buildings across eight villages, identifying six initial building types, which are categorized into traditional-style, style-coordinated, and other-style buildings based on the traditional village protection and development plan, as shown in Fig. 5. Next, Labelme software is used to annotate buildings in the UAV shadow, constructing the instance segmentation dataset, which is then trained and evaluated under the TensorFlow 2.5 deep learning framework. The model achieves precision scores of 0.91, 0.75, and 0.65 for traditional-style, style-coordinated, and other-style buildings, respectively; recall values of 0.92, 0.86, and 0.75; and F1 scores of 0.91, 0.79, and 0.69, demonstrating a clear improvement over existing models.

To handle large-format UAV images, the study uses a moving window method, ignoring edge pixels37 and adjusting for the scale of traditional village buildings with a window size of 600 × 600 pixels. This approach effectively mitigates issues with fragmented building recognition caused by large image sizes. Post-processing includes regularization algorithms for building morphology and anomaly filtering38 to enhance the completeness and smoothness of building contours, resulting in more accurate building vector information. Finally, the recognition results are cross-checked through visual interpretation and refined with minimal manual correction to ensure the accuracy and scientific integrity of the architectural texture analysis.

Morphological index methodology

To assess the multi-dimensional architectural texture of traditional villages, this study adopts the morphology index method for quantitative evaluation. A comprehensive index system covering six dimensions—scale, proportion, size, pattern, orientation, and boundary—is developed, based on the “Indicator System of Evaluation and Recognition of Traditional Villages (for Trial Implementation)”39 and existing studies39.

First, in the context of value assessment for traditional Chinese villages, two dimensions, scale and proportion, are used to evaluate the overall building area and the proportion of different building types. Next, within the scale dimension, two indicators—average building area and diversity—are introduced to assess the overall architectural scale characteristics of the villages. In the pattern dimension, three indicators—building distribution aggregation, building distribution disorder, and the number of clusters—are used to evaluate the spatial structure of traditional villages. For the orientation dimension, the ratio of south-facing buildings and the alignment of clusters are incorporated to evaluate the orientation characteristics of buildings and the overall long-axis distribution of the settlement. Finally, in the boundary dimension, two indicators—boundary morphological complexity and boundary aspect ratio—are introduced to characterize the macro features of the settlement. The calculation methods and detailed explanations for all indicators are provided in Table 2.

Correlation analysis methods

Correlation analysis is a standard method for assessing the strength and direction of relationships between variables. Common approaches include Spearman and Pearson correlation coefficient analyses, which are widely used in architectural heritage preservation8,40, environmental science41, and ecological conservation42. In practice, to ensure the reliability of correlation assumptions and avoid random results, a two-tailed test is typically applied to assess the significance of the correlation coefficient. A value below 0.05 indicates a significant correlation, while values above 0.05 are considered insignificant. However, differences in linearity assumptions, data distribution, and outliers may lead to conflicting results when applying these two methods to the same dataset. In this study, to enhance objectivity and scientific rigor, both Spearman and Pearson correlation analyses are combined to explore the intrinsic correlations between the quantitative indicators of architectural texture.

Results

The data conversion process for architectural information extraction is illustrated in Fig. 6. First, the improved Mask R-CNN model is applied to UAV images of 27 traditional villages, generating a grayscale map where varying grayscale levels represent different architectural types. After minimal manual adjustment and morphological optimization, the final vector map is produced, containing detailed information on building types, scales, and distribution. This completes the architectural data collection for the 27 traditional villages.

Traditional village architecture extraction data conversion process, the labeling order is the same as that in Fig. 1.

Descriptive statistics of the architectural texture of traditional villages

The statistical analysis results of all architectural texture indicators are presented in Table 3 and visualized through violin plots in Fig. 7. OS ranges from 5388 to 102,150 square meters, with a coefficient of variation of 0.91, indicating the highest intrinsic heterogeneity among all indicators. PTB varies between 0.08 and 0.81, with a mean of 0.46 and a coefficient of variation of 0.48, suggesting that the overall integrity of traditional features in Beijing’s villages is relatively high and stable. PCB ranges from 0.01 to 0.65, with a coefficient of variation of 0.76, reflecting a greater variability in coordinated architectural features across different villages. AFA and DFA in the scale dimension, as well as ABD and BDD in the pattern dimension, have the lowest coefficients of variation, indicating a more uniform architectural scale and distribution pattern. NG, BO, and CO have coefficients of variation greater than 0.5, signaling higher territorial variation in these indicators across villages. In the boundary dimension, the coefficients of variation for VBC and BAR are below 0.5, suggesting that boundary features are less effective in distinguishing architectural texture. In conclusion, the study reveals significant descriptive differences among the architectural texture indicators in Beijing’s traditional villages.

Divergent characteristics of the architectural texture of traditional villages

To further explore the distribution characteristics of different indicators, this study uses histograms to visualize the evaluation results of architectural texture across multiple dimensions. As shown in Fig. 8, under the scale dimension, 24 OS values fall within 35,000 square meters. Additionally, the areas of Nanjiao Village, Gubeikou Village, and Hexi Village exceed 70,000 square meters, reflecting the generally small-scale nature of the villages, influenced by their mountainous environment. In the proportion dimension, PTB values are primarily centered around 60%, with 15 villages having more than 50% of traditional buildings. Meanwhile, 81% of villages exhibit less than 40% PCB, with a few villages, such as Yanhecheng Village and Xihulin Village, having higher values. Overall, the traditional villages in Beijing maintain a high level of traditional landscape integrity. In the pattern dimension, 89% of NG values are below 10, 85% of BDD values range from 0.3 to 0.7, and 78% of ABD values lie between 0.5 and 0.8. These values reflect the architectural texture of traditional villages in Beijing, characterized by fewer clusters, moderate aggregation, and higher levels of disorder. Under the scale dimension, 96% of AFA values are between 30 and 80 square meters, contrasting with the more concentrated distribution of DFA values between 0.25 and 0.35. This indicates significant variability in AFA values across villages, although architectural scales within individual villages tend to be more uniform. In the boundary dimension, 89% of VBC values are between 4.3 and 10, with a concentration around 6, all higher than the circular 2√π, suggesting that boundary features are complex and varied. Additionally, 52% of BAR values exceed 2, indicating that settlements primarily follow linear development patterns. Under the orientation dimension, the number of villages with east-west long-axis orientations gradually decreases compared to those with north-south orientations, with 70% of CO values falling within 45 degrees of east-west to north or south, reflecting the dominance of the east-west direction in settlement orientation. The BO values range from 0 to 65%, with 63% of villages having fewer than 30% of south-facing buildings, indicating a diverse range of architectural orientations across the traditional villages of Beijing. The study reveals significant dimensional differences in the architectural texture of Beijing’s traditional villages. Overall, the histogram frequency distribution enhances the understanding of these differentiation characteristics, such as distribution density, range, maximum and minimum values, and more.

Correlation analysis of quantitative indicators of architectural texture

Exploring the underlying structure between architectural texture indicators helps to comprehensively understand the formation and evolutionary patterns of traditional village architectural textures, providing effective strategies for the sustainable development of settlement architectural styles. The results of the Pearson and Spearman correlation analyses are presented in Fig. 9. Asterisks (*) in the upper-right corner indicate correlations with a significance level below 0.05. The findings reveal a high degree of consistency between the two correlation methods, both highlighting the significant correlations between several indicators. Eight indicators—OS, PTB, PCB, DFA, ABD, NG, BO, and VBC—showed substantial associations across all six dimensions. Specifically, OS demonstrated a strong positive correlation with NG, VBC, and BO, suggesting that larger clusters tend to have more groups, more complex boundaries, and a greater number of south-facing buildings. In the second group, PTB showed a significant negative correlation with DFA and PCB, while PCB exhibited a positive correlation with DFA. This indicates that villages with more traditional buildings tend to have fewer style-coordinated buildings and lower architectural scale diversity. Conversely, villages with more style-coordinated buildings showed higher architectural scale diversity. In the third group, ABD negatively correlated with NG and VBC, suggesting that villages with higher aggregation levels may have fewer clusters and simpler boundary patterns.

Discussion

In light of the large number of traditional villages, their wide distribution, and complex environments, as well as the inefficiencies of traditional evaluation methods that rely heavily on subjective judgments, this study for the first time constructs a comprehensive methodological system integrating UAV remote sensing, deep learning technology, multi-dimensional morphological indexes, and statistical and correlation analyses. Using 27 traditional villages in Beijing as examples, the study demonstrates the effectiveness and innovation of combining new technology with traditional methodologies, and discusses the multi-dimensional characteristics and internal correlation structure of the building texture, which is of great significance for realizing the digital protection and deep understanding of the traditional village building texture.

First, the integration of UAV remote sensing and deep learning technologies has revolutionized the evaluation of architectural textures in traditional villages, particularly in regions like Beijing, where these villages are numerous and widely distributed. Traditional methods, which often rely on subjective judgments, are increasingly being supplemented by more objective, technology-driven approaches. UAVs facilitate the acquisition of high-precision data in rural areas, especially in traditional villages located in remote mountainous regions. This data plays a crucial role in overcoming the challenges of identifying traditional villages, which are often characterized by target aggregation, small-scale structures, and multiple temporal states. The deep learning model used in this study is instance segmentation, a versatile model that effectively combines the benefits of target detection and semantic segmentation34. It allows for the simultaneous extraction of architectural type, boundary, and location information, which lays the foundation for developing a multidimensional architectural texture index system. The Mask R-CNN model optimized with PAFPN and ASPP achieves higher accuracy in extracting architectural details from traditional village buildings. During application, it was observed that building value correlates positively with extraction accuracy. Specifically, traditional-style buildings, which have more uniform forms, tend to yield higher extraction accuracy. In contrast, buildings with coordinated styles, such as double-sloped roofs and diverse materials, as well as buildings of other styles with varied roof forms, exhibit greater heterogeneity, requiring more sophisticated deep learning recognition. This integrated approach, combining UAV imagery, deep learning, and traditional methods, offers significant advantages that have often been overlooked in previous studies17,23,30, making it highly valuable for evaluating the architectural texture of traditional villages.

Second, as we delve deeper into the architectural texture of Beijing’s traditional villages, we observe notable heterogeneity, especially in scale, proportion, and orientation, which highlights the distinct characteristics of different villages. For instance, the village size dimension reveals that the majority of these villages feature small architectural structures that harmonize with the natural environment, creating a distinctive and idyllic landscape. However, larger villages such as Nanjiao Village, Gubeikou Village, and Hexi Village, with areas exceeding 70,000 square meters, often owe their size to special historical functions, resource endowments, or geographical advantages43. These larger villages exhibit more complex architectural layouts and spatial planning, reflecting a rich history shaped by cultural, historical, and socio-economic forces.

Moving to the proportion dimension, the overall higher integrity of traditional features indicates that Beijing’s traditional villages have successfully preserved their historical and cultural essence. However, the high proportion of coordinated buildings in certain towns highlights the challenges posed by urbanization, where old and new structures must be integrated and replaced44. Villages with a high degree of traditional integrity should focus on enhancing protection efforts to prevent overdevelopment and irrational transformation45. On the other hand, villages with a significant proportion of coordinated buildings should focus on strengthening the unity between traditional and modern architectural styles, promoting awareness of traditional building preservation46, encouraging the restoration of traditional features, and fostering cultural heritage.

Exploring the building pattern dimension reveals the distinctiveness of Beijing’s traditional villages in terms of spatial organization. The small number of clusters may be linked to factors such as village population size, family structures10, and land distribution. The degree of agglomeration remains stable across villages, which not only ensures close architectural connections but also preserves spatial independence, improving residents’ living interactions47, agricultural production48, and energy efficiency47,49. Greater disorder suggests that the development of these villages does not strictly adhere to plans but has organically evolved due to the influence of natural topography, cultural backgrounds, and environmental factors such as floods and disasters50. This contrasts sharply with modern communities and provides a valuable threshold for reference when planning the expansion of villages, supporting the creation of vibrant and adaptable rural spaces.

The building scale dimension reflects the combined influence of regional culture and geography. The uniformity in architectural scale within villages may be linked to traditional construction techniques, norms, and the availability of materials51, indicating a stable social structure and cultural tradition. However, variations in architectural scale between villages could stem from differing levels of economic development, functional needs, and geographical environments52, particularly in areas like Miyun, Fangshan, and Mentougou districts. This diversity in architecture and culture reflects the regional reality and offers a foundation for scale control to sustain traditional architectural textures.

The complex boundary patterns result from the interaction between villages and their natural surroundings. This feature reflects the organization of public spaces and facilitates communication between buildings53. The boundary elements contribute to landscape formation and spatial definition, and these should be utilized to highlight the region’s unique characteristics. The linear constraints emphasize the need to respect the natural conditions of rivers, mountains, ancient pathways, and other resources54,55 when planning future village development. Maintaining ecological patterns and landscape styles should be prioritized to preserve the village’s connection to its environment.

The orientation dimension is deeply influenced by the geographic environment and settlement strategies. Due to the complexity of the mountainous terrain, village buildings do not strictly follow the traditional north-south orientation. Instead, they are flexibly arranged according to topography, sunlight, ventilation, and other natural factors56. This diversity not only reflects the residents’ wisdom in adapting to their environment but also embodies passive strategies for optimizing lighting, ventilation, and landscape, which are of significant value for modern architectural design.

Third, we further explored the correlation structure of architectural texture through correlation coefficient analysis, which reveals the underlying patterns of village-scale expansion, traditional building distribution, and the development of historical and cultural contexts.

The significant positive correlation between OS and NG, VBC, and BO reveals a series of changing patterns in the process of village-scale expansion. During this expansion, villages such as Hexi Village (Fig. 10), where the surrounding terrain is conducive to construction, have increased public spaces and roads to meet operational needs, thus creating more building clusters. At the same time, they are not significantly constrained by the surrounding mountainous environment, showcasing the advantages of a north-south orientation. Moving forward, small-scale villages should maintain their existing patterns, boundary forms, and building orientations to adapt to terrain-specific construction techniques. Larger settlements, on the other hand, should regulate the expansion direction, boundary forms, and building scales through rational planning to enhance spatial quality and improve the overall landscape.

The correlation between PTB, DFA, and PCB suggests that traditional buildings typically have relatively balanced forms. In contrast, style-coordinated buildings exhibit greater diversity in scale, which leads to an increase in PCB and DFA. On the other hand, a higher proportion of PTB correlates with a decrease in DFA. Villages such as Xihulin Village (Fig. 11) have seen an increase in the number of modern double-slope buildings in recent years due to rapid urbanization, resulting in a more diverse range of building scales and a reduction in the traditional landscape value of the village. In response, future construction standards and scales for style-coordinated buildings should be strictly regulated to prevent the uncontrolled expansion of such buildings from disrupting the village’s overall architectural balance. Additionally, targeted restoration and renewal strategies should be developed, such as encouraging residents to adopt traditional building materials and forms for renovations and new construction, in order to minimize the impact of modern building elements on the traditional landscape.

The correlations between ABD, NG, and VBC reflect the unique relationship between history, culture, and village development. Ji Jiaying Village (Fig. 12), for instance, has a relatively high ABD but contains only one cluster, with a VBC of 4.99. In contrast, Gubeikou Village (Fig. 13) has a lower ABD but the highest number of clusters, 24, and a VBC as high as 14.16. While many villages share historical ties to the Great Wall’s city ports, Ji Jiaying Village has expanded less beyond the city wall and retains a more military-style settlement layout, with a regular settlement boundary pattern57. For villages with a focus on historical and cultural preservation, particularly those that retain military settlement characteristics, it is crucial to maintain the original layout and boundary features. Conversely, villages with more diverse functional needs, such as tourism development or those located in more open geographic environments, may promote boundary space openness. This approach would better accommodate the needs of various user groups and enrich the esthetic experience, based on a moderate increase in the number of clusters and the diversification of boundary forms.

In summary, among all the indicators, NG has the highest number of associated indicators (four), followed by OS with three associated indicators. DFA, VBC, PTB, ABD, PCB, and BO each have two related indicators, while BAR, CO, BDD, and AFA have no associated indicators. Evaluation indicators with a larger number of associations and a higher coefficient of variation tend to have a stronger global influence, and changes in these indicators may drive the evolution of the entire settlement. In the future conservation and development planning of traditional villages, key indicators such as NG, OS, and PTB should be prioritized and managed to ensure the sustainable development of the architectural texture of traditional villages through strategic guidance.

Although this study improves the scientific evaluation of the architectural texture of traditional villages and promotes the application of new technologies in their preservation, there remains room for further improvement in comprehensive assessments of architectural features, initial screening, and dynamic monitoring across a large number of villages. First, since buildings typically consist of three parts: the roof, façade, and foundation, evaluating architectural features solely from the perspective of the roof may lead to one-sided results. Future work should strengthen the extraction of architectural information from multiple perspectives. Secondly, the model’s training relies heavily on labeled data, and for some traditional villages with unique architectural styles or specific historical and cultural backgrounds, there may be insufficient data, which could affect the accuracy and generalizability of the model. Additionally, China’s assessment model, from local declarations to expert reviews, is susceptible to local biases, national protection policies, and conflicting interests58. As a result, some esthetically appealing villages may be overlooked. Therefore, it is worth exploring in depth future training that involves comprehensive architectural labeling, top-down screening, and ongoing monitoring.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available on reasonable request.

Code availability

The code used and/or analysed during the current study is available on reasonable request.

References

Guo, Z. & Sun, L. The planning, development, and management of tourism: the case of Dangjia, an ancient village in China. Tour. Manag. 56, 52–62 (2016).

Zhao, Y., Zhan, Q., Du, G. & Wei, Y. The effects of involvement, authenticity, and destination image on tourist satisfaction in the context of Chinese ancient village tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 60, 51–62 (2024).

Fu, J., Zhou, J. & Deng, Y. Heritage values of ancient vernacular residences in traditional villages in Western Hunan, China: spatial patterns and influencing factors. Build. Environ. 188, 107473 (2021).

Dayu, H. T. Z. Research on the evolution of selection indicators and value assessment of Chinese traditional villages. City Plan. Rev. 46, 6 (2022).

Qi, L. et al. Research on parametric analysis and simulation application of spatial texture in traditional villages: a case study of Cantonese traditional villages. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 23, 1–26 (2024).

Whitehand, J., Samuels, I., Conzen, M. P. & Conzen, M. R. G. 1960: Alnwick, Northumberland: a study in town-plan analysis. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 33, 859–864 (2009).

Peng, P. et al. Quantitative research on the degree of disorder of traditional settlements: a case study of Liangjia Village, Jingxing, Hebei Province. Herit. Sci. 12, 109 (2024).

Ge, H. et al. Study on space diversity and influencing factors of Tunpu settlement in central Guizhou Province of China. Herit. Sci. 10, 1–18 (2022).

Zhang, C. et al. Analyses of the spatial morphology of traditional Yunnan Villages utilizing unmanned aerial vehicle remote sensing. Land 12, 2011 (2023).

Nie, Z. et al. Quantitative research on the form of traditional villages based on the space gene—a case study of Shibadong Village in Western Hunan, China. Sustainability 14, 8965 (2022).

Yang, X., Song, K. & Pu, F. Laws and trends of the evolution of traditional villages in plane pattern.Sustainability 12, 3005 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Baimu, S., Tong, J. & Wang, W. Geometric spatial structure of traditional Tibetan settlements of Degger County, China: a case study of four villages. Front. Archit. Res. 7, 304–316 (2018).

Zhu, Q. & Liu, S. Spatial morphological characteristics and evolution of traditional villages in the mountainous area of southwest Zhejiang. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 12, 317 (2023).

An, Y., Wu, X., Liu, R., Liu, L. & Liu, P. Quantitative analysis village spatial morphology using “SPSS + GIS” approach: a case study of Linxia Hui autonomous prefecture. Sustainability 15, 16828 (2023).

Lin,Z., Liang,Y. & Liu,X. Study on spatial form evolution of traditional villages in Jiuguan under the influence of historic transportation network. Herit. Sci. 12, 29 (2024).

Deng, X., Liang, Y., Li, X. & Xu, W. Recognition and spatial distribution of rural buildings in Vietnam. Land 12, 2142 (2023).

Monna, F. et al. Deep learning to detect built cultural heritage from satellite imagery. -Spatial distribution and size of vernacular houses in Sumba. Indones. J. Cult. Herit. 52, 171–183 (2021).

Liu, X., Li, Y., Wu, Y. & Li, C. The spatial pedigree in traditional villages under the perspective of urban regeneration—taking 728 villages in Jiangnan Region, China as cases. Land 11, 1561 (2022).

Huang, X. & Gu, Y. Revisiting the spatial form of traditional villages in Chaoshan, China. Open House Int. 45, 297–311 (2020).

Chen, X., Xie, W. & Li, H. The spatial evolution process, characteristics, and driving factors of traditional villages from the perspective of the cultural ecosystem: a case study of Chengkan Village. Habitat Int. 104, 102250 (2020).

Yudantini, N. & Jones, D. The conservation of Balinese traditional architecture: the integration of village pattern and housing pattern in indigenous villages. Appl. Mech. Mater. 747, 84–87 (2015).

Wang, T., Chen, J., Liu, L. & Guo, L. A review: how deep learning technology impacts the evaluation of traditional village landscapes. Buildings 13, 525 (2023).

Zhang, M., Li, Z. & Wu, X. Semantic segmentation method accelerated quantitative analysis of the spatial characteristics of traditional villages. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. XLVI-M-1-2021, 933–939 (2021).

Qian, Z. et al. Simultaneous extraction of spatial and attributional building information across large-scale urban landscapes from high-resolution satellite imagery. Sustain. Cities Soc. 106, 105393 (2024).

Wang, P. et al. Provincial supervision exploration of historic cities, towns, and villages in China based on deep learning and GIS- taking Zhejiang Province as an example. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. X-M-1-2023, 277–284 (2023).

Bakirman, T. et al. Implementation of ultra-light UAV systems for cultural heritage documentation. J. Cult. Herit. 44, 174–184 (2020).

Liu, C., Cao, Y., Yang, C., Zhou, Y. & Ai, M. Pattern identification and analysis for the traditional village using low altitude UAV-borne remote sensing: multifeatured geospatial data to support rural landscape investigation, documentation and management. J. Cult. Herit. 44, 185–195 (2020).

Meng, C. E. et al. Automatic classification of rural building characteristics using deep learning methods on oblique photography. Build. Simul. 15, 1161–1174 (2021).

Wang, W. et al. Traditional village building extraction based on improved Mask R-CNN: a case study of Beijing, China. Remote Sens. 15, 2616 (2023).

Li, X., Yang, Y., Sun, C. & Fan, Y. Investigation, evaluation, and dynamic monitoring of traditional Chinese village buildings based on unmanned aerial vehicle images and deep learning methods. Sustainability 16, 8954 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Improved mask R-CNN for rural building roof type recognition from UAV high-resolution images: a case study in Hunan Province, China. Remote Sens. 14, 265 (2022).

Zhao, X. & Wu, Z. Unveiling the urban morphology of small towns in the eastern Qinba Mountains: integrating earth observation and morphometric analysis. Buildings 14, 2015 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. EO + morphometrics: understanding cities through urban morphology at large scale. Landsc. Urban Plan. 233, 104691 (2023).

He, K., Gkioxari, G., Dollár, P., Girshick, & R. B. Mask R-CNN. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 42, 386–397 (2017).

Liu, S., Qi, L., Qin, H., Shi, J. & Jia, J. Path aggregation network for instance segmentation. IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. 2018, 8759–8768 (2018).

Chen, L.-C., Papandreou, G., Schroff, F. & Adam, H. Rethinking atrous convolution for semantic image segmentation. Comput. Vision Pattern Recogn. abs/1706.05587 (2017).

Liang, S., Wang, M. & Qiao, B. Research on building extraction from high-resolution remote sensing image based on improved U-Net. In: Jain, L. C., Kountchev, R. & Shi, J. (eds.) 3D Imaging Technologies—Multi-dimensional Signal Processing and Deep Learning 191–201 (Springer Singapore, 2021).

Jun, C., Riqiang, W., Wei, J., Jiao, Y. & Lijuan, L. DeepLabV3+ improved algorithm for national building recognition in traditional village aerial images. Bull. Surv. Mapp. 69, 49–53 (2023).

Evaluation and identification index system of traditional villages (Trial). (Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development) https://www.dmctv.cn/zcfgShow.aspx?id=14 (2012).

Cheng, G. et al. Research on the spatial sequence of building facades in Huizhou regional traditional villages. Buildings 13, 174 (2023).

Xu, H., Croot, P. & Zhang, C. Exploration of the spatially varying relationships between lead and aluminium concentrations in the topsoil of northern half of Ireland using Geographically weighted Pearson correlation coefficient. Geoderma 409, 115640 (2022).

Zhang, N., Xu, H., Cheng, Y. & Hou, Q. Quantification and analysis study for the morphological characteristics of urban waterbodies: evidences from 42 cases in China. Ecol. Indic. 166, 112458 (2024).

Zhifeng, Z. & Qiangguo, M. Investigation and study on rural settlements in Nanjiao Village, Fangshan District, Beijing. Tradit. Chin. Archit. Gardens 6, 64–69 (2018).

Huang, Y. et al. Development types and design guidelines for the conservation and utilization of spatial environment in traditional villages in Southern China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 23, 1699–1716 (2024).

Li, G., Chen, B., Zhu, J. & Sun, L. Traditional Village research based on culture-landscape genes: a case of Tujia traditional villages in Shizhu, Chongqing, China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 23, 325–343 (2024).

Qi, Y. et al. Quantitative analysis and cause exploration of architectural feature changes in a traditional Chinese village: Lingquan Village, Heyang County, Shaanxi Province. Land 12, 886 (2023).

Zhang, D., Shi, Z. & Cheng, M. A study on the spatial pattern of traditional villages from the perspective of courtyard house distribution. Buildings 13, 1913 (2023).

Xun, L. I. et al. Spatial distribution of rural building in China: remote sensing interpretation and density analysis. Acta Geogr. Sin. 77, 835–851 (2022).

Li, Z., Chen, Y., Zhang, H. & Wang, S. Relationships among village spatial form, electricity use, and photovoltaic potential: evidence from 120 villages in Huaiyuan County, China. Energy Build. 325, 115027 (2024).

Deng, Y., Liang, S., Zhou, W. & Wang, P. Perspective on traditional village spatial order based on directed weighted networks: a case study of Banliang Village. Int. J. Digit. Earth 17, 2383430 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Renovation of traditional residential buildings in Lijiang based on AHP-QFD methodology: a case study of the Wenzhi Village. Buildings 13, 2055 (2023).

Indraganti, M. Understanding the climate-sensitive architecture of Marikal, a village in Telangana region in Andhra Pradesh, India. Build. Environ. 45, 2709–2722 (2010).

Liu, L. & Liu, Z. Delineation of traditional village boundaries: the case of Haishangqiao village in the Yiluo River Basin, China. PLoS ONE 17, e0279042 (2022).

Zhang, J., Tang, X., Yu, Z., Xiong, S. & Yang, F. Water-town settlement landscape atlas in the east river delta. China Land 13, 149 (2024).

Xu, H., Guo, Q., Siqin, C., Li, Y. & Gao, F. Study of settlement patterns in farming–pastoral zones in eastern inner Mongolia using planar quantization and cluster analysis. Sustainability 15, 15077 (2023).

Rabie, S., Sangin, H. & Zandieh, M. The orientation of village, the most important factor in rural sustainability in cold climate (case study: Masuleh and Uramantakht). J. Sol. Energy Res. 6, 761–776 (2021).

Shuo, L., Yang, S. & Jie, Z. Study on the spatial morphological characteristics of rural settlements along the Ming Great Wall in Beijing. Dev. Small Cities Towns 42, 50–58 (2024).

Yanli, K. Research on traditional villages’ protection system in China. Mod. Urban Res. 31, 2–9 (2016).

Zhang, X., Zhou, L. & Zhou, T. Quantitative analysis of spatial gene in traditional villages: a case study of Korean traditional villages in northeast China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 23, 1–12 (2024).

Wang, X., Tang, P. & Cai, C. Traditional Chinese village morphological feature extraction and cluster analysis based on multi-source data and machine learning. In Proc. Conference on Computer Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia (CAADRIA) 179–188 (2023). CEPT University.

Zhang, X., Li, J. & Xu, J. Micro-scale analysis and optimization of rural settlement spatial patterns: a case study of Huanglong Town, Dayu County. Land 13, 966 (2024).

Wang, X., Zhu, X. & Tang, P. Characterization of the chinese traditional villages based on the morphological clustering and knowledge graph. In Proc. Conference on Computer Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia (CAADRIA) (2024). Singapore University of Technology and Design.

Ma, W. et al. Complex buildings orientation recognition and description based on vector reconstruction. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 123, 103486 (2023).

Zhang, W. & Yang, H. Quantitative research of traditional village morphology based on spatial genes: a case study of Shaanxi province, China. Sustainability 16, 9003 (2024).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers who provided insightful comments on improving this article. This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number: 52478039), the National Key Research and Development Plan (Project number: 2023YFC3803900), the National Natural Science Foundation of China Youth Project (Grant number: 52108036), the National Natural Science Foundation of China Key project (Grant number: 51938002), supported by Beijing Natural Science Foundation (Grant number: 8242008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yang Shi: Writing–original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Wenke Wang: Writing–original draft, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Conceptualization. Jie Zhang: Supervision, Project administration. Dong Li: Software. Fei Liu: Resources. Wensheng Li: Resources.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, Y., Wang, W., Zhang, J. et al. UAV remote sensing and deep learning for assessing and optimizing architectural texture in traditional villages. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 325 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01804-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01804-w