Abstract

The industrial fabrication of useful, persistently luminescent paints started in the 1930s. They were used to make safety signs for places where blanking was commanded or as slowly decaying lighting during blackouts, e.g., in shelters. In this work, we investigated samples of painted plaster from a cellar room of the fortress Špilberk in Brno occupied by the Wehrmacht during World War 2. The investigation of material composition indicates the presence of the white reflecting base layer of Ba(Sr)SO4 covered by the luminophore layer of ZnS:Cu. Optical properties (luminescence spectra and decay kinetics) were investigated in detail and compared with samples of similar age that remained in the university collections and with a modern material (LumiNova). The emission spectrum and visual colour of WW2 luminophore match very well with the most common green luminophore ZnS:Cu, as well as with LumiNova.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Luminescence is spontaneous non-equilibrium radiation from condensed matter excited to higher electronic or vibrational states1,2. Different types of luminescence are discerned according to the means of excitation (e.g., cathodoluminescence, radioluminescence, electroluminescence, etc.). Here, we shall concentrate on photoluminescence, which is excited by light. In organic luminophores, one can distinguish two main luminescence processes called fluorescence and phosphorescence, where the first process is spin-allowed with fast relaxation (ps to ns decay time), and the second one is “forbidden” with slow transition (μs to ms). We prefer to keep the term photoluminescence (PL) for inorganic luminophores, albeit fluorescence and phosphorescence are often used3.

There is a special kind of inorganic luminophores that show long-lasting emission decay (after switching-off an excitation source) visible for minutes or even hours. This effect is (again erroneously) called phosphorescence, but the appropriate name is persistent luminescence4 – more precisely, the mechanism is, in fact, thermoluminescence at ambient temperature. In such materials, the energy given to electronic excited states can be “stored” in shallow traps from which it is released by thermal vibrations and transferred to emission centres (usually related to impurities introduced by doping)5.

In this work, we investigate the properties of persistently luminescent paints from the first half of the 20th century and compare them with currently produced materials. Such comparison can serve as a guide for renovation or restoration6,7 of, e.g., shelters from the 2nd World War (WW2).

Persistently luminescent stones were the first inorganic objects demonstrating “cold-light” emission that were discovered by humans. Many minerals can produce efficient photoluminescence, but we cannot distinguish faint luminescence from much stronger reflection and scattering of excitation light. In order to achieve that, one needs either an invisible excitation source (ultraviolet (UV) illumination in a dark room) or filters that can stop the scattered excitation light (e.g., blue light). However, a persistently luminescent material/mineral excited by the sunshine can emit light for some time when brought into a dark room. Thanks to the alchemist literature, the first recorded case of luminescent material called “Bologna stone” dates back to 16028,9. At that time, Vincenzo Casciarolo, an Italian shoemaker and “amateur alchemist,” collected barite (BaSO4) stones at Monte Paderno near Bologna. Then he tried to anneal these stones, and so he unintentionally reduced the material to BaS, including various impurities, mostly Cu. The resulting material BaS:Cu produced yellow persistent luminescence.

The modern history of luminophores started with the discovery of X-rays by W. Roentgen in 1895. These mysterious rays produced visible luminescence in the glass tube walls and other materials. The possible link between luminescence and X-rays was explored (among others) by Henry Becquerel (1852–1908), who (along with his father Edmond) previously studied the luminescence of minerals. When testing the green-luminescent uranium minerals, he discovered (1896) that the uranium sample produces radiation (detected by a photographic plate) even without any excitation10. This effect was named “natural radioactivity” by Marie Curie, who took over the investigation of these subjects with her husband, Pierre Curie11.

It should be noted that some of the inorganic pigments fabricated for, e.g., paintings, can demonstrate photoluminescence, albeit unintentionally. One example is a white pigment fabricated as a coprecipitate of ZnS and BaSO4. It was manufactured on a commercial scale from 1874. One of its names was lithopone12.

Thus, by the end of the 19th century, luminophores became very important for science and technique development, allowing the visualization of ionizing radiation (scintillator screens) or electron rays in cathode ray tubes (oscilloscopes and later TV-sets). The most systematic and inventive studies of luminophores were performed at the dawn of the 20th century by Philipp Lenard (1862–1947, Nobel Prize in physics laureate in 1905 for X-ray studies), after whom a group of luminophores based on alkali earth metal sulphides (CaS, SrS and BaS) with impurities was known as the “Lenard’s phosphors” (Fig. 1)13,14. Fortunately, Lenard included in his study also ZnS (synthesized by Sidot in 186615 and known as “Sidot’s blende”), which became the most commonly applied luminophore for many decades to come. Lenard summarized his work in the two-volume monograph16. A set of the Lenard’s phosphors was preserved in collections of Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Charles University in Prague (Fig. 1). The object is labelled by a wax stamp “Vorlesung” (Lecture) and was, most probably, used by Prof. Bernhard Gudden (1892–1945) during his lectures in Institute of Physics, German Charles University (1939–1945)17,18.

After the Great War (WW1), the first commercial production of luminophores was initiated. We can mention the company of the Switzer brothers in the USA19,20 or Riedel-de Haën, Seelze, Germany (namely producing chemicals for gas lamp mantles (Th: Ce), luminescent dyes (nachleuchtender Stoffe; Glow-in-the-Dark) from 1914, and luminophores for television screens from 1935)21. WW2 marked the widespread application of luminophores for dials in airplane cockpits, radar screens, night-vision devices, or for signalling, including persistently luminescent materials for shelters, etc.

Interesting information on applications of persistent luminophores with many details can be found in a textbook by Nikolaus Riehl (1901–1990), published in Berlin 194122, where he wrote (now citing from the original text): “While in peacetime the practical applications of luminescent colours are essentially limited to the manufacture of luminescent jewellery items, toys, Christmas decorations, etc., their applications in the darkening of buildings in wartime are extremely extensive. […] The most commonly used luminescent materials are zinc sulphide activated with copper and, in some cases, strontium sulphide activated with bismuth. While ZnSCu gives off a green glow, SrSBi glows blue-green. […] A luminescent paint (Clarolit) has recently been developed that can be applied using a conventional painting technique and can, therefore, be used by any painter without any special prior knowledge. Since this new luminescent paint is also almost ten times cheaper than the luminescent paints used up to now, it can be used to paint large areas, such as the entire walls of a room. It produces white, well-covering surfaces and can be used both as a first coat of paint for new rooms and as an additional coat of paint for rooms that have already been painted. According to unpublished measurements by W. Arndt, this luminous paint, when used as a wall paint, produces an illuminance (1 m above the floor in the middle of the room) of 10–20 Nox (= 1 ×·10-2 to 2 × 10-2 lux) in a room with a floor area of around 5 × 6 m and a height of 3 m immediately after the normal lighting is switched off. After 3 hours, the illuminance drops to around 0.1 Nox. These are lighting values that allow safe orientation in the room.”

The trademarks, Permaphan, Clarophan, and Clarolit belonged to Auergesellschaft (N. Riehl was director of the scientific headquarters in that company). Other persistent German luminophores during WW2 were produced by IG Farben (Lumogen – several colour variants, based on organic dyes). It is worth noting that the main disadvantage of Sr-containing luminophores was instability due to their hygroscopic properties.

The development of new persistently luminescent materials, obviously, continues23. Modern materials exploit rare earth metals (lanthanides) as efficient emitting centres. One of the best-performing and widely used materials is LumiNova (produced by Nemoto & Co., Ltd. from 1998), based on strontium aluminate doped with Eu and Dy (SrAl2O4:Eu2+, Dy3+)24. However, the “good old” ZnS-based luminophores are still in production.

Methods

The luminescence of the paint on plaster was visually inspected in situ using a UV-LED torch in a dark room. Small pieces of loose plaster were placed in plastic Petri dishes using tweezers.

The optical characterization was performed with the home-built micro-spectroscopy set-up based on the inverted optical microscope (Olympus IX-71) coupled to the 30-cm imaging spectrograph (Acton Spectra Pro 2300i) with the back-illuminated CCD camera (Princeton Instruments Spec-10:400B). A low magnification objective lens (Olympus UPLFLN 4x/0.13) was used. PL was measured in the epi-fluorescence geometry with excitation by the diode laser continuously emitting at 405 nm (Omicron LDM405.120.CWA.L). Colour micro-photographs were taken using a compact CMOS camera (Thorlabs Kiralux LP126CU). The spectral response of the set-up was calibrated using the secondary standard of spectral irradiance (45 W tungsten-halogen lamp, Newport Oriel).

The structural and compositional characterization was performed after optical characterization in order to avoid possible effects of the X-ray exposure on the photoluminescence of the studied samples. XRD was obtained using the Seifert XRD7 diffractometer equipped with a copper X-ray tube and scintillation detector. XRF spectra were measured using the Rigaku Nex CG table top energy dispersive spectrometer.

Collection of historical samples

The samples of luminescent plaster were collected in the ancient fortress Špilberk in Brno (Spielberg, Brünn, in German). A castle was built on this hill in the 13th century, rebuilt into a baroque fortress in the 17th century, and later adapted into a prison. During WW2, when the Germans occupied Czechia, the fortress was adapted (1939–1941) for the purposes of the German army (Wehrmacht)25. After liberation in 1945, the Czechoslovak army used the barracks until 1959. Since 1960, Špilberk is the residence of the Museum of the City of Brno.

Two casemate rooms at the east entrance (Fig. 2) still have walls partially covered by a persistently luminescent paint (these rooms are normally not accessible to visitors). They were possibly used as a stock room or shelter. When the samples were collected, the most preserved painting was around the entrance to room 1 (Fig. 3), while on the west wall of room 2, the painted plaster was already highly damaged (Fig. 4). We collected three loose pieces of plaster with paint (that were about to fall off) from three locations on the west wall in room 2. The total volume of collected material was only about 1 cm3 (Fig. 2b). Due to its fragility, the collected plaster had a form of small grains with a typical size of a few mm, which further fragmented when manipulated.

For comparison, we measured the optical properties of the set of luminophores from the university collections that were introduced above (Fig. 1). The age of these materials should be like that of the painted plaster. As we did not dare break the glass tubes, the material composition of these powders was not verified.

Results

Material structure and composition

In order to reveal the nature of the luminophore in the paint layer on plaster, we needed to determine its composition and crystal structure. The selected instruments had to be able to work with a small number of fragile samples.

The crystalline structure was determined by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a Seifert XRD7 diffractometer equipped with a copper X-ray tube and scintillation detector (Fig. 5). The diffraction pattern indicates the dominant presence of ZnS and BaSO4 (Fig. 3).

The elemental analysis of samples was performed using the X-ray fluorescence (XRF) with the Rigaku Nex CG table top energy dispersive spectrometer (Fig. 6). The dominant presence of Zn, S, and Ba is seen at the luminophore side. As expected, we see mainly Si, Ca, Fe, and Cl at the plaster side. The typical lime plaster is made from sand and slaked lime (calcium hydroxide), hence it contains mainly silica with iron impurity (typical local sand in Czechia is from river deposits, so it can contain some salt as well) and calcium carbonate (formed by the reaction of slaked lime with air).

These results indicate that barium sulphate BaSO4, which is known as highly reflecting white paint, was used as the base layer with the function to reflect back the luminescence and the excitation light passing through the luminophore upper layer to increase luminescence brightness. Sr is a common impurity of Ba due to chemical similarity. The luminophore itself is probably ZnS doped by Cu, the most often used dopant in green ZnS-based luminophores26. However, due to the low amount of tested luminophore and the concentration of Cu (usually about 5 ppm), we were not able to confirm the presence of copper (or any other dopant) by the applied methods.

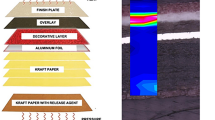

In addition, we investigated the extremely fragile plaster pieces under an optical microscope – combining the white-LED reflectance and the violet-LED excited luminescence imaging (see Fig. 7). In some spots of the plaster grains, we can see the white layer with just small spots of luminescent paint sitting on it. The layer thickness estimated by refocusing the microscope is roughly around 100 µm and a few hundred µm for the luminescent and reflecting layers, respectively. This observation provides additional evidence of the presence of two layers: the base reflecting layer (composed of BaSO4) and the upper layer of the ZnS-based luminophore.

a Optical microscopy image taken under the white-LED illumination and b luminescence image under 405-nm-excitation of the same location on a plaster grain, which is almost entirely covered by the white reflecting base layer (except the yellowish part in the upper left corner indicated as p). The lower panel demonstrates that the luminescent layer is preserved only at a fraction of the white layer and on top of it.

Optical properties

The most important properties of persistently luminescent materials are the emission spectrum and the decay kinetics after the excitation is switched off (sometimes called afterglow). We measured these properties using the properly calibrated micro-spectroscopy set-up27 and applying the 405-nm diode laser for excitation. The painted plaster is compared with the historical luminophore powder marked SrZnFl (the central tube in Fig. 1) and modern luminophore LumiNova in the form of plastic foil (optical properties of such luminophores based on the lanthanide dopants are insensitive to the encapsulating matrix; therefore, we used the form, which was the most easily available).

Photoluminescence spectra of the three materials (under the 405-nm excitation) are shown in Fig. 8, revealing a very good match of the emission band, i.e., having almost identical colour. The historical paint has a small emission shoulder in the blue-violet spectral range around 440 nm – possibly it indicated admixture of blue-emitting ZnS pigment (ZnS:Ag). But the colour appearance of all three samples is the same (the human eye is quite insensitive in the violet-blue region).

PL decay kinetics are measured by detecting a series of PL spectra after a shutter stops the laser excitation. The samples were kept in the dark for at least 30 minutes before the experiment. The excitation duration was 1 minute – we found that such duration well saturates the initial luminescence signal amplitude for the studied set of samples (one can see this saturation at times before zero in Fig. 9a). The decay kinetics of persistent luminophores is characterized by a fast drop of emission amplitude within a second followed by much slower decay (Fig. 9a). At longer decay times the kinetics roughly follow the power-law function t-x, where x is around 1.4 for both historical materials and close to 1 for LumiNova (Fig. 9b). Interestingly, the initial drop is much lower for the powder sample than for the paint (being similar to LumiNova) – it may be due to the reduced degradation of powder sealed in the glass tube.

Discussion

The samples of persistently luminescent materials collected in the casemate of Špilberk reveal the presence of ZnS and BaSO4 pigments (using XRD and XRF analysis). From the optical microscopy, we can see that the plaster was covered by a layer of white paint based on BaSO4, and the luminescent layer was painted on it. We were not able to detect the activator doping in ZnS. However, we can suppose that it was copper as the most common dopant in green persistently luminescent ZnS (usually present in a concentration of a few ppm). That means that the luminescent paint corresponds to Clarolit, produced by Auergesellschaft.

By comparing the luminescence spectra of historical samples with a modern material (LumiNova), we have shown that the emission colour match is excellent. The persistent luminescence duration of modern materials is much longer, which may be due to the optimization of current materials, but also because of the degradation of historical pigments. Indeed, when we take the information from the Riehl’s book22 cited above – claiming the Clarolit emission decreased by about two orders of magnitude in three hours – it is even better performance than we detected for LumiNova (Fig. 9b). We can speculate how precise the historical characterization was, but this parameter was definitely crucial for the commercial success of persistent luminophores.

It should be noted that the ZnS-based luminophores (e.g., NightGlo™ NG-200 or NG-880 by the company DayGlo, Cleveland, OH) are still in production and may be tested for the purposes of restoration or renovation. Also, white paints based on BaSO4 are broadly available and currently applied, e.g., to reduce the heating of buildings by reflection of solar light28.

The presented work aimed to demonstrate the testing of historical luminophores and compare their composition with historical documents. By the applied methods, we were not able to detect dopants presented in very low concentrations. Also, the other components of the studied paints, especially the binder, cannot be specified from our data. The future work must include a broader portfolio of methods, like Raman scattering spectroscopy or electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy12. It would be desirable to collect samples from more locations and perform the first optical measurements in situ before acquiring the samples29. However, we currently know of only one more location with a luminescent cellar from WW2 in Jihlava (Iglau) in Czechia.

In conclusion, persistently luminescent materials started to be commonly available in the 1920s and 1930s. Then, they were applied during WW2, especially for signalling and safety-light purposes. We have collected samples of such paints and compared them with similar contemporary pigments and a modern material. Our study of material composition shows that WW2 paint on plaster contains a white base layer of BaSO4 covered by the ZnS:Cu luminophore (possibly the paint produced under the trademark Clarophan by Auergesellschaft). The luminescent spectrum peak (~525 nm) and colour match very well with the contemporary “Lenard phosphor” SrZnFl and the modern LumiNova material. The persistent luminescence duration of modern materials is much improved, but the historical information reporting excellent luminescence duration suggests that persistent luminescence degraded significantly with time and/or the historical measurements are inaccurate.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data analysis in this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Pelant I., Valenta J. Luminescence Spectroscopy of Semiconductors. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012.

IUPAC Goldbook: Luminescence: https://goldbook.iupac.org/terms/view/L03641.

Liu R. S., Wang X. Phosphor Handbook: Fundamentals of Luminescence. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2022.

Brito, H. F. et al. Persistent luminescence mechanisms: human imagination at work. Opt. Mater. Express 2, 371–381 (2012).

Chiatti, C., Fabiani, C. & Pisello, A. L. Long persistent luminescence: a road map toward promising future developments in energy and environmental science. Annu Rev. Mater. Res. 51, 409–433 (2021).

Schmidtke Sobeck, S. J. & Smith, G. D. Shedding light on daylight fluorescent artists’ pigments, part 2: spectralproperties and light stability. J. Am. Inst. Conserv.62, 222–238 (2023).

Álvarez-Martín, A. et al. Multi-modal approach for the characterization of resin carriers in Daylight Fluorescent Pigments. Microchem J. 159, 105340 (2020).

Lastusaari, M. et al. The Bologna Stone: history’s first persistent luminescent material. Eur. J. Miner. 24, 885–890 (2012).

Hölsä J. Persistent Luminescence Beats the Afterglow: 400 Years of Persistent Luminescence. ECS Interface. 2009:42–45.

Allisy, A. Henry Becquerel: The discovery of radioactivity. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 68, 3–10 (1996).

Curie E. Madame Curie: A biography. Da Capo Press, 2001. (New York: Doubleday & Co., 1937)

Bellei, S. et al. Multianalytical study of historical luminescent lithopone for the detection of impurities and trace metal ions. Anal. Chem. 87, 6049–6056 (2015).

Pelant, I. & Valenta, J. From history of luminescence: Philipp Eduard Anton Lenard. Czechoslovak J. Phys. 65, 287–290 (2015). (in Czech).

Xu, J. & Tanabe, S. Persistent luminescence instead of phosphorescence: History, mechanism, and perspective. J. Lumin 205, 581–620 (2019).

Kolar, Z. I. & den Hollander, W. A centennial of spinthariscope and scintillation counting. Appl Radiat. Isot. 2004, 261–266 (2003).

Lenard P. Phosphorescence and Fluorescence. In: Schmidt F., Tomaschek R., editors. Handbook of Experimental Physics. Band 23. Leipzig: Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft M. B. H.; 1928. (in German)

Gisolf, J. H. Memory of Bernhard Friedrich Adolf Gudden. Arch. der Elektr. Übertragung 3, 111–112 (1949).

Frank, H. Memory of Bernhard Gudden and semiconductor physics development in German Institute of Physics in Prague. Czech. J. Phys. 65, 90–94 (2015).

Thorne Baker, T. Fluorescent Inks and Paints. J. Roy. Soc. Arts 99, 763–776 (1951).

Lindblom K. DayGlo fluorescent pigments: brighter, longer lasting color. ACS Landmarks. 2012. [online] https://www.acs.org/content/dam/acsorg/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/dayglo/dayglo-fluorescent-pigments-historical-resource.pdf.

Pfeiffer K. H., editor. 100 years of Chemiestandort Seelze. Seelze: Museumsverein für die Stadt Seelze e.V.; 2002. (in German) [on-line] http://www.heimatmuseum-seelze.de/100_Jahre_Chemiestandort_Seelze.web.pdf.

Riehl N. Physics and Technical Applications of Luminescence (Physik und technische Anwendungen der Lumineszenz). Berlin: Verlag von Julius Springer; 1941. (in German).

Huang, K. et al. Designing next generation of persistent luminescence: recent advances in uniform persistent luminescence nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 34, 2107962 (2022).

Matsuzawa, T., Aoki, Y., Takeuchi, N. & Murayama, Y. A new long phosphorescent phosphor with high brightness, SrAl2O4:Eu2+,Dy3+. J. Electrochem Soc. 143, 2670–2673 (1996).

Kroupa P. Špilberk – Reconstruction During World War 2. Forum Brunense. 1990;95–106.

Smet, P. F., Moreels, I., Hens, Z. & Poelman, D. Luminescence in sulfides: a rich history and a bright future. Materials 3, 2834–2883 (2010).

Valenta, J. & Greben, M. Radiometric calibration of optical microscopy and microspectroscopy apparata over a broad spectral range using a special thin-film luminescence standard. AIP Adv. 5, 047131 (2015).

Li, X., Peoples, J., Yao, P. & Ruan, X. Ultrawhite BaSO4 Paints and Films for Remarkable Daytime Subambient Radiative Cooling. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 21733–21739 (2021).

Valenta, J. et al. Radiometric characterization of daytime luminescent materials directly under the solar illumination. AIP Adv. 14, 105113 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the director of the Museum of City Brno for allowing the collection of samples of luminescent plaster in Špilberk castle, for providing the documentation (plans and photos), and permission to adapt and reproduce them. JV thanks to late Prof. Karel Vacek for preserving the historical luminophores over many decades. AF would like to thank the National Heritage Institute Brno for the opportunity to access their archives. This work was a proof-of-concept work performed within the institutional support from Charles University (Cooperatio).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.V. proposed the project, collected samples, performed optical characterization, and wrote the paper. S.D. performed structural and compositional characterization, participated in manuscript finalization. AF managed permissions, studied archives, and participated in optical characterization and manuscript finalization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Valenta, J., Danis, S. & Fucikova, A. Persistently luminescent materials used by the Germans during World War 2 and related contemporary luminophores. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 253 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01838-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01838-0