Abstract

Since ancient times, the Sichuan-Tibet Railway corridor has given birth to a wealth of cultural heritage. This study employs GSA, ESTDA, and OPGD to investigate the spatial patterns and influencing factors of cultural heritage in counties along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway. The results show that: (1) The quantity and spatial pattern of cultural heritage in counties along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway have dynamically changed over time, exhibiting a quasi-periodic characteristic of weak agglomeration—strong agglomeration—weak agglomeration. (2) The local spatial structure of cultural heritage quantity and the overall fluctuation amplitude of spatial dependency direction are small, indicating strong spatial integration. The local spatial autocorrelation structure is relatively stable, with evident transfer inertia and path dependency, and significant regional coordinated development relationships, especially in the areas at both ends of the railway. (3) The spatial pattern of cultural heritage along the route is the result of the interaction of multi-factor, especially historical and cultural factors. The research results have practical value for the excavation, protection and utilization of cultural heritage resources along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As a major strategic project in China, the area along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway is an important ethnic area in China, with profound cultural and historical accumulation. Since ancient times, it has been an important channel connecting Sichuan and Tibet (Tea-Horse Ancient Road) and an important linear cultural heritage in China1. The so-called linear cultural heritage refers to the material and intangible cultural heritage groups in the linear or belt-shaped areas with special cultural resources2. It has distinct characteristics such as unbalanced distribution of local resources, large time and space span, and many and complex components3. These unique ethnic historical and cultural heritage groups are testimonies to the region’s historical, cultural, social, and economic development and are crucial for maintaining regional cultural diversity and historical continuity4. In addition, linear cultural heritage has achieved remarkable results in resource integration and sustainable development through resource advantages and agglomeration effects, and is regarded as a growth driver for regional development5.

Throughout the research history of linear cultural heritage, related research originated in the early 20 th century in Europe and the United States and other countries to connect cultural elements such as monuments, squares, parks and other green landscape axes and boulevards, and then derived cultural routes and heritage corridor systems6, setting off a worldwide research boom in linear cultural heritage. The research content mainly includes landscape design and planning7,8, operation management9, regional cooperation10, spatial structure and management11 of linear cultural heritage, which basically involves the whole process of heritage utilization. In China, with the promotion of the strategic deployment of the Great Wall, the Long March, the Yellow River, the Yangtze River National Cultural Park and the construction of cultural belts, as well as the successful application of cultural heritage such as the Grand Canal, the protection, inheritance and utilization of linear cultural heritage has become a hot topic. Relevant research mainly focuses on the concept analysis of linear cultural heritage12, landscape value assessment13, sustainability assessment14, protection and management3, residents’ value perception of heritage sites15, heritage corridor construction16 and so on. The research objects focus on the Grand Canal, the Great Wall, the Silk Road, the Yunnan-Tibet Tea Horse Road, the Yunnan-Vietnam Railway, the Middle East Railway, and the ancient Qin-Shu Road. In addition, under the background of global urbanization and modernization, the original function of linear cultural heritage is limited or destroyed, and it is driven by economic development and cultural inheritance. Exploring the functional evolution and transformation of linear cultural heritage has become a key research topic at home and abroad. Many scholars at home and abroad have also affirmed the multiple functions of linear cultural heritage in religious culture17, cultural inheritance18, leisure and recreation19, popular science education20, and ecological environment21. In particular, the combination of linear cultural heritage and tourism has spawned related topics such as tourism product development22, tourism value assessment23, tourism stakeholders6, and tourism effects24.

In recent years, with the development of GIS and other geographic information technologies, international research on linear cultural heritage has gradually shifted from qualitative to quantitative approaches, focusing primarily on spatial analysis and evaluation of cultural heritage groups. The research object is divided into two categories: material cultural heritage and intangible cultural heritage, including traditional villages, ancient buildings, ancient sites, traditional skills, traditional medicine and other types25,26,27. Methods include kernel density analysis28, geographic concentration index29, and spatial autocorrelation27. Research scales range from global30, national31, and regional32 to provincial33 and municipal34 levels. At the same time, scholars have also revealed the driving mechanism of the spatial pattern of cultural heritage through geodetector27, geographically weighted regression35, buffer zones26 and other methods. The results show that cultural heritage is the product of the interaction of historical, natural, social and cultural environments, including topography, hydrological conditions, vegetation cover, population density, economic development level, traffic conditions, historical environment36,37,38. In general, the spatial pattern of cultural heritage in different periods is related to the natural geographical environment and cultural and historical conditions. To a certain extent, it is a geographical paradigm for the coordinated development of human-land relations.

However, the existing research mostly focuses on the static analysis and evaluation of linear cultural heritage. Even for the spatial research of linear cultural heritage, it only stays in the static spatial description of its ethnic group. At present, there is little systematic research on linear cultural heritage and its ethnic groups as a whole, and there is a lack of spatial co-opetition analysis of the development and evolution of cultural heritage in different periods between regions. In addition, the research objects are mainly the Grand Canal, the Great Wall Cultural Park, and the Silk Road. There are few studies on the linear region along the modern railway, and most of them use qualitative methods15. The theory of linear cultural heritage corridor points out that transportation infrastructure is not only a channel for material flow, but also a link for cultural dissemination and integration. As an important corridor connecting Chinese and Tibetan cultures, the distribution and evolution of linear cultural heritage along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway has unique research and development value. The Sichuan-Tibet Railway not only overlaps with the ancient tea-horse road in space, but also has a unique temporal pattern of its cultural heritage groups due to its complex terrain and changeable climatic conditions. Due to geographical restrictions and lack of concepts, compared with the depth and breadth of other cultural route heritage research in China, the research on Sichuan-Tibet Railway is not systematic, and the in-depth investigation and theoretical research work can not be carried out under the guidance of a complete theoretical system. The object of study is more focused on its ecological and environmental impact, the composition of cultural heritage, the value of cultural heritage and other static, point-like elements, as well as the operation of heritage protection, heritage development and other aspects. There is less attention to the dynamic evolution of the overall spatial pattern of linear cultural heritage and the analysis of neighborhood competition and cooperation, but it also provides research paradigms and theoretical references for related research in the region39. With the construction and operation of the railway, cultural heritage in these counties will face unprecedented opportunities and challenges. On one hand, the railway’s opening is expected to promote the protection and inheritance of cultural heritage by enhancing public awareness and conservation consciousness through cultural and tourism activities. On the other hand, rapid economic development and urbanization may pose potential threats to these fragile cultural heritage. Therefore, systematically characterizing the spatial-temporal patterns of cultural heritage in counties along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway and clarifying the influencing factors of its spatial distribution are of great theoretical and practical significance for formulating scientific and rational cultural heritage protection strategies and achieving sustainable development.

Therefore, this paper takes the county-level administrative regions along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway as the research area, and systematically excavates the linear cultural heritage of the Sichuan-Tibet Railway and constructs a database based on the census data of Chinese cultural relics. Then, by introducing dynamic research methods such as exploratory spatio-temporal data analysis, the spatio-temporal distribution characteristics and evolution rules of cultural heritage are quantitatively analyzed. On this basis, this paper constructs an index system of influencing factors from three dimensions: natural geography, social economy, and historical culture. Using the OPGD, this paper analyzes the impact and interaction of different factors on the spatial pattern of cultural heritage (Fig. 1). This paper aims to provide a scientific basis for the protection and utilization of cultural heritage along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway, and also provide a new paradigm reference for the study of other traffic-type linear cultural heritage, such as spatio-temporal dynamics and spatio-temporal interaction.

Methods

Study area overview

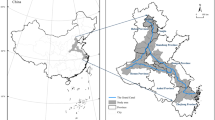

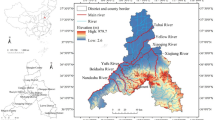

The Sichuan-Tibet Railway is an east-west rapid railway in southwestern China and the second railway into Tibet. It starts from Chengdu in the east and ends in Lhasa in the west, passing through five prefectures (cities) including Ya’an, Garze, Changdu, Nyingchi, and Shannan, as well as more than 30 counties (Fig. 2). The railway spans China’s first and second topographic steps, with a total length of 1,838 kilometers and a cumulative elevation gain of 14,000 meters. It traverses numerous famous mountains, rivers, and geomorphological units40. Additionally, the railway corridor was an important route of the ancient Tea Horse Road and an important linear cultural heritage in China. Along the route, there is a bright culture of the Han and Tibetan, which has nurtured 16 types of cultural heritage groups with national characteristics, such as ancient sites, architecture, grotto temples, traditional music, dance, and folklore, with great potential for cultural and tourism development.

Method selection basis and introduction

The research of traditional cultural heritage mostly relies on static methods such as nearest neighbor index and kernel density analysis, which can only reflect the spatial pattern characteristics of a certain time section, and it is difficult to capture the temporal and spatial dynamic evolution law of cultural heritage. In addition, the traditional geodetector is limited by the discrete method and the series, and the ability to explain the interaction of multiple factors is limited, which cannot reveal the comprehensive driving mechanism of multi-dimensional factors on the spatial pattern of cultural heritage. Therefore, this study dynamically presents the stability and transfer inertia of the local spatial structure of cultural heritage through the LISA time path, LISA space-time transition and LISA space-time interaction analysis of ESTDA, which breaks through the “snapshot” limitation of traditional static spatial analysis. At the same time, the geodetector based on parameter optimization can explore the potential interactive effects of geological variables and provide various visual spatial analysis results. The combination of the two provides a methodological innovation for the spatio-temporal dynamic analysis and multi-dimensional driving mechanism research of linear regional cultural heritage.

Global spatial autocorrelation. This study employs the Moran’s I index to analyze the spatial pattern of cultural heritage in counties along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway41, with the formula as follows:

Where Global Moran’s I denotes the autocorrelation coefficient; n is the number of counties, Xi and Xj represent the quantities of cultural heritage in counties i and j; \(\bar{{\rm{X}}\,}\) represents the mean value, and \({\omega }_{{ij}}\) represents the spatial weight. If the Moran’s I index is greater than zero and the Z-score is greater than 1.65, it indicates a positive global correlation. The counties with an approximate number of cultural heritage are spatially clustered. The larger the Z-score, the smaller the P value, the more significant the agglomeration state. If it is negative, it represents a global negative correlation, and the number of cultural heritage varies greatly among different counties. If the Z-score is between-1.65 and 1.65, it indicates that the cultural heritage is randomly distributed in space.

Exploratory spatial-temporal data analysis. This study utilizes Exploratory Spatial-Temporal Data Analysis (ESTDA) to reveal the interactive characteristics of cultural heritage in counties along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway across both spatial and temporal scales, dynamically presenting static Local Indicators of Spatial Autocorrelation (LISA). It includes LISA time path, LISA spatial-temporal transition and LISA spatial-temporal network.

The LISA time path includes three indicators: relative length, curvature, and movement direction, which respectively characterize the dynamic features of local spatial structure, the fluctuation of local spatial dependency direction, and the integration of local spatial structure42,43. The formulas are as follows:

Where \(\varPsi\) is the relative length; \(\varPhi\) is bending degree; T is the annual interval; \({L}_{i,t}\) is the LISA coordinate of county i in t years \(({y}_{i,t},y{L}_{i,t})\); \(d({L}_{i,t},{L}_{i,t+1})\) is the migration distance from t year to t + 1 year in i county; \(d({L}_{i,t},{L}_{i,T})\) the migration distance of county i from year t to the end of the year. If \({\varPsi }_{i}\) and \({\varPhi }_{i}\) is larger, it indicates that the region has a dynamic local spatial structure and direction. On the contrary, the spatial structure and state are stable.

To further reveal the spatial-temporal evolution characteristics of cultural heritage in counties along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway, this study combines the LISA time path with the traditional Markov chain to form a spatial-temporal transition matrix44,45, as shown in Table 1.

This paper reveals the characteristics of LISA spatio-temporal network between counties and neighborhoods by calculating the covariance coefficient of LISA spatio-temporal trajectory between counties and neighborhoods, which mainly includes four types : strong positive correlation, weak positive correlation, strong negative correlation and weak negative correlation.

Optimal parameter geographical detector. Parameter optimization is to combine different discretization classification methods and stages of continuous variables. According to the combination of discretization parameters corresponding to the highest interpretation of variables, it is optimal to carry out more accurate spatial analysis. The parameter optimization in this paper is mainly spatial discretization optimization. Among them, the classification method uses natural breaks, equal breaks, standard breaks, geometric breaks and quantile breaks. According to the principle of not too much46, the grades are set to 3–7 categories.

On the basis of parameter optimization, the degree of explanatory power of single factor to the spatial differentiation of cultural heritage is analyzed by factor detection. The calculation formula47 is :

Where N and σ2 respectively represent the variance of the number of units and Y in the study area. Y consists of L layers (h = 1, 2… L). q represents the explanatory ability of each influence factor to Y, and its value is strictly within [0, 1]. The larger the value of q, the stronger the explanatory ability of independent variable X to dependent variable Y, and vice versa.

Furthermore, the interaction detector is used to identify the interactions between influencing factors, i.e., to assess the combined effects (enhancement or reduction) of factor pairs on the spatial pattern of cultural heritage, as shown in Fig. 3.

Indicator system and data sources

Based on the core viewpoint of cultural landscape theory, the spatial pattern of cultural heritage is essentially the result of the long-term interaction of the triple composite system of “natural base-human activities-cultural inheritance”. Based on the three-dimensional dialectical framework of Lefebvre’s spatial production theory, this study constructs a composite dynamic mechanism of “environmental adaptability-socio-economic drive-cultural reproduction” : (1) The natural geographical environment forms the basic framework of cultural heritage distribution through topographic barrier effect and water corridor effect. (2) Socio-economic factors are driven by gradient through spatial differentiation of population aggregation, transportation network and economic activities. (3) Historical and cultural elements realize the spatial and temporal reproduction of cultural genes through ethnic migration, religious communication, settlement succession and other processes. Therefore, based on the relevant research27,28,29,32,48,49, this paper constructs an index system including ten factors in three dimensions of natural geography, social economy and historical culture, and comprehensively discusses the influencing factors of the spatial pattern of cultural heritage in counties along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway (Table 2).

Specifically, elevation (X1) and slope (X2) are important factors affecting regional climate, hydrology, landform, and human habitability, thereby influencing the spatial pattern of cultural heritage. Additionally, the distribution of river systems (X3) is closely related to human activities. To determine its impact, this study calculates the nearest distance between cultural heritage sites and river systems. Ancient cities (X4), as concentrated areas of early human activities, provide a basis for the emergence and development of cultural heritage. The historical transportation conditions (X5) in the region, such as the ancient Tea Horse Road, promoted economic trade and cultural exchanges along the line. Due to the lack of data on the Tea Horse Road, this study uses the modern transportation routes G317 and G318, which closely match the ancient road, as the transportation factor. Population-dense areas (X6) and economically developed core regions (X7) are inevitably areas where culture flourished in ancient times, facilitating the formation and inheritance of cultural heritage. The proportion of ethnic minorities (X8) promotes the emergence of numerous cultural heritage with unique folk customs. The scale and authenticity of historical settlements (X9) are interdependent with the distribution and quantity of cultural heritage. The number of religious and sacrificial sites (X10) reflects the degree of religious belief in the region and can better illustrate the impact of regional religious culture on the spatial differentiation of cultural heritage.

Cultural heritage data were obtained from the national and provincial (autonomous region) level intangible cultural heritage lists and cultural relic protection unit lists published by cultural relics bureaus and tourism departments at all levels. The spatial coordinates of cultural heritage were acquired using Baidu Coordinate Selector (for intangible cultural heritage, the place of origin was selected), converted to WGS_1984 coordinates, and corrected to obtain a total of 702 cultural heritage sites. The vector data of provincial, municipal, and county-level administrative boundaries and government seats were sourced from the Resource and Environmental Science Data Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The vector data of major transportation routes and river systems were obtained from the 1:250,000 basic geographical database. The 90-meter DEM data were sourced from the geographical spatial data cloud, and elevation and slope data were derived from the DEM. County-level population density, minority population numbers, and GDP statistics were obtained from the 2023 statistical yearbooks of respective districts and counties. The number of national historical and cultural cities, historical and cultural towns and historical and cultural villages, and the number of traditional Chinese villages are obtained through the corresponding official websites of the country, such as the digital museum of traditional Chinese villages. The religious and sacrificial sites come from the State Religious Affairs Bureau and local religious management departments.

Results

Spatial-temporal evolution characteristics of cultural heritage in counties along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway

Temporal evolution characteristics. Based on the characteristics of Chinese historical evolution and related studies15, this study divides the cultural heritage along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway into five periods: prehistory to pre-Qin, Qin-Han-Sui-Tang, Song and Yuan, Ming and Qing, and modern China (Fig. 4). The radar charts shows that the number of cultural heritage in each period has increased step by step, with the highest proportion in the Ming and Qing (39.32%). The second is the Qin-Han-Sui-Tang, with 196 different types of cultural heritage. The Song and Yuan and modern China accounted for 12.68% and 11.11% respectively, while the prehistoric to pre-Qin accounted for only 8.97%. This change is closely related to the political and economic pattern and the intensity of ethnic exchanges in different historical stages.

According to historical records, due to the unique natural geographical environment, Han and Tibetan ethnic groups began to interact in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau region in ancient times, forming ancient sites such as Karuo and Qugong with cultural features of the Yellow River basin29. However, due to the low productivity level and sparse population of primitive society, the number of cultural heritage in this period was relatively small. In the Qin-Han-Sui-Tang period, with the establishment of the central government in the eastern counties of Tibet, the introduction of Han clothing and smelting technology promoted the development of Tibetan local culture. In particular, the entry of Princess Wencheng of the Tang Dynasty into Tibet (A.D. 641), the spread of Bon religion, and the “Tang-Tibet Alliance Stele” greatly promoted the cultural exchanges between the Central Plains and Tibet, and gave birth to many cultural heritage with national characteristics, an increase of 311% over the previous period. Among them, traditional skills, ancient buildings, traditional dances, and folk customs are the main ones. In the Song and Yuan period, the rise of the Tea Horse Road and Kublai Khan’s reverence for Tibetan Buddhism led to the construction of rich Tibetan Buddhist temples and grotto temples along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway. The further integration of Han and Tibetan culture became the main driving force for the birth of cultural heritage. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the Central Plains placed great emphasis on transportation construction in Tibet and supported the local economy. The Han-Tibet tea trade reached its peak, and the Sichuan-Tibet Tea Horse Road became an important channel for long-term economic trade and cultural exchange between Han and Tibetans. As a result, the number of cultural heritage reached a peak during this period, including national cultural heritage such as Potala Palace, Sera Monastery, Batang String Dance and Kangmian Satangka. Subsequently, in modern China, revolutionary wars and post-founding support and construction in Tibet left behind many significant revolutionary sites and memorials, bringing the number and types of cultural heritage to new heights. Overall, the temporal evolution of the number of cultural heritage along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway presents the stage characteristics of “low-level equilibrium, policy-driven growth, economic and trade dominance, institutional attenuation”. The fundamental mechanism lies in the synergy of the governance intensity of the central government, the scale of cross-regional economic exchanges and the protection policies of cultural heritage.

Spatial evolution characteristics. This study employs global autocorrelation to examine the overall spatial clustering characteristics of cultural heritage in counties along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway during the study period (Table 3). Overall, the global Moran’s I index ranges from 0.01 to 0.22. Except for the prehistoric to pre-Qin period, there is a significant positive spatial autocorrelation at least at the 10% level through the significance test, indicating significant positive spatial autocorrelation. This suggests that counties with higher (or lower) quantities of cultural heritage tend to cluster spatially. In terms of trend, the global Moran’s I index first increased significantly and then decreased slowly during the study period, showing a quasi-periodic characteristic of weak agglomeration- strong agglomeration- weak agglomeration. This indicates that the quantity of cultural heritage in counties along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway exhibited a growth pole pattern from the Qin-Han-Sui-Tang periods to the Song and Yuan period. Particularly during the Tang Dynasty, policies of marriage alliances and economic trade led to frequent cultural exchanges between Han and Tibetan ethnic groups in Tibet, causing high-quantity counties to gradually cluster spatially, such as Chengguan District, Duilongdeqing District, and Naidong District in Tibet. In contrast, counties in Sichuan such as Yajiang County, Kangding City, and Tianquan County had fewer cultural heritage sites due to geographical and transportation constraints. Subsequently, a more balanced trend emerged, with the number of cultural heritage sites in Karuo District and Litang District also increasing, and the spatial diffusion effect becoming stronger (Fig. 5).

Spatial-temporal evolution characteristics. In terms of LISA time path analysis, firstly, during the study period, 15 counties had a LISA time path relative length greater than 1, mainly distributed in the Tibetan area, including Duilongdeqing District, Chengguan District, and Qushui County. This indicates a strong dynamic local spatial structure. By region, the dynamic nature of the Tibetan area (1.254) is greater than that of the Sichuan area (0.746), with the highest value in Karuo District (2.469) and the lowest in Bayi District (0.391), suggesting that the LISA time path relative length decreases from west to east. The reason is that the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau has historically been a close interaction zone between Han and Tibetan ethnic groups, and rich cultural heritage has been generated in different historical periods with the deepening of exchanges, resulting in a more fluctuating local spatial structure. In contrast, the Sichuan area had fewer cultural heritage sites in the early stages, with significant increases only during the Ming and Qing period and modern China. Overall, the local spatial structure in the Sichuan area is more stable (Fig. 6a).

Secondly, 21 counties had a LISA time path curvature below the mean (2.171), indicating a relatively stable local spatial dependency direction. Overall, these counties are less influenced by neighborhood spatial spillover or polarization effects, with a more stable increase over time. By region, the mean curvature of the Tibetan area (2.064) is lower than that of the Sichuan area (2.279), indicating that the Sichuan area has a more dynamic local spatial dependency direction. Counties such as Pujiang County, Baiyu County, and Kangding City in Sichuan have more complex spatial structure changes and greater fluctuations due to neighborhood spatial influences. Combined with the LISA time path relative length, although the overall change in the Tibetan area is greater, the process is smoother. In contrast, the Sichuan area, despite smaller overall changes, has more fluctuations and directional changes. This is due to population turmoil caused by dynastic changes, which has a significant impact on the inheritance and development of cultural heritage (Fig. 6b).

Thirdly, the movement direction of the LISA time path reveals the characteristics of local spatial integration of cultural heritage quantities. Based on the direction and distance of coordinate movement, the movement direction can be divided into four categories: positive synergistic growth type (win-win), negative synergistic growth type (lose-lose), and reverse growth type (win-lose and lose-win). There are 22 counties with synergistic growth types, accounting for about 68.75% of the total study units, indicating that the local spatial structure of cultural heritage shows a trend of cooperation greater than competition, with strong spatial integration. The positive synergistic growth type is mainly distributed at both ends of the railway, gradually becoming the core area for the inheritance and protection of cultural heritage. In contrast, the central region, limited by natural geography, political environment, and social economy factors, has become a negative synergistic growth area. The reverse growth type is mainly distributed in some counties and cities in Garze Prefecture and Chengdu, with lower spatial integration due to policy competition and ecological conflicts (Fig. 6c).

Considering that LISA time path analysis alone cannot systematically reveal the transfer characteristics of local spatial autocorrelation types, this study further uses LISA spatial-temporal transition to describe the evolution trend of local spatial autocorrelation types of cultural heritage quantities in counties along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway.

According to Table 4, the local autocorrelation characteristics of cultural heritage quantities in counties along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway exhibit significant transfer inertia and path dependency. During the study period, 12 counties experienced spatial-temporal transitions, involving types I, II, and III, including HH-LL (0.063), HH-HL (0.031), LH-HH (0.031), LH-LL (0.125), LL-HL (0.063), HL-HH (0.031), and HL-LL (0.031). These types of counties have active transitions in local Moran’s I index types, especially Baiyu County and Basu County, which transitioned from the HH type in prehistory to pre-Qin to the LL type in modern China. This indicates significant changes in both their own and neighboring local Moran’s I index types, with evident spatial-temporal pattern evolution characteristics. Conversely, ~62.5% of counties did not experience spatial-temporal transitions (type I), including HH-HH (0.094), HL-HL (0.094), LH-LH (0.031), and LL-LL (0.406). This suggests that the local spatial autocorrelation characteristics of cultural heritage quantities in counties along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway are relatively stable and difficult to change their autocorrelation types. Counties with LL-LL types, mostly in Garze Prefecture and Ya’an City, have long maintained low levels of cultural heritage quantities and exhibit a low-low clustering distribution trend with neighboring areas. In contrast, Chengguan District, Duilongdeqing District, Gongga County, Naidong District, and Zhanang County currently have high-high clustering states. This is mainly due to their roles as political, economic, and cultural centers of the Tibet Autonomous Region. Historical cultural integration and modern policy benefits have made them core areas for cultural heritage distribution along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway, with a long-term sustained trend.

During the inheritance and development of cultural heritage, neighboring counties along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway may have relationships of regional cooperation or spatial-temporal competition. To reveal the local autocorrelation characteristics of cultural heritage inheritance and development along the railway, this study depicts the spatial-temporal network pattern of cultural heritage quantities in counties along the line (Fig. 7).

From the geographical network and topological network of cultural heritage, the spatial-temporal pattern of cultural heritage quantities is mainly characterized by positive correlation, with 33 pairs accounting for 78.57%. Among them, there are 22 strong positive correlation, such as between Chengguan District and Zhanang County, Chengguan District and Duilongdeqing District, and Qingyang District and Wenjiang District. This indicates that the spatial-temporal evolution of cultural heritage quantities in counties along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway shows a strong spatial integration process. Additionally, some counties, including Naidong District and Sangri County, Litang County and Yajiang County, Qionglai City and Xinjin District, and Naidong District and Qusong County, exhibit strong negative correlation. The evolution process of cultural heritage quantities in these counties has certain competitive characteristics, possibly due to uneven population distribution, social development levels, and cultural resource endowments. The inheritance and protection of cultural heritage in individual counties have regional exclusivity. Overall, the spatial-temporal pattern of cultural heritage quantities in counties along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway is significant. The eastern and western ends are collaborative development areas, mainly characterized by strong positive correlation, while the central section is a differentiated development area, dominated by weak negative correlation.

Analysis of influencing factors of spatial pattern of cultural heritage in counties along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway

Identification of optimal parameters. Different discretization combinations have a significant impact on the driving mechanism of the spatial pattern of cultural heritage along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway (Fig. 8). Existing studies usually use the combination of the largest q value as the optimal parameter for data discretization46. Taking elevation (X1) as an example, when the classification method is quantile breaks and the number of categories is 7, the q value is the largest. Similarly, the slope (X2), river distribution (X3), distance to historical cities (X4), population density (X6) and ethnic cultural background (X8) were divided into 7, 7, 7, 7, and 6 categories by quantile breaks. The distance to historical transportation routes (X5) is divided into 7 categories by standard breaks. GDP (X7) is divided into five categories by geometric breaks. According to the natural breaks, the historical settlement environment (X9) and the religious belief level (X10) are divided into 7 and 5 categories respectively.

Analysis of factor detector. This study employs the OPGD to explore the influencing factors of the spatial pattern of cultural heritage in counties along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway, revealing the significant roles of natural geography, social economy, and historical culture in the protection and inheritance of cultural heritage in the region. Different factors in each dimension have varying explanatory power for the spatial pattern of cultural heritage along the railway, all passing the significance test at the 0.01 level (Table 5).

Regarding natural geography, the unique plateau topography, complex terrain, and variable climatic conditions of the Sichuan-Tibet Railway region significantly impact the spatial distribution of cultural heritage. Specifically, the q values of elevation (X1) and river distribution (X3) are 0.4551 and 0.1332, respectively, indicating that topography and hydrological conditions play a key role in shaping the spatial pattern of cultural heritage. The special climate and terrain of high-altitude areas directly affect the preservation and distribution of cultural heritage, while river distribution influences human activity patterns and the formation of cultural heritage. Statistics show that 67.81% of cultural heritage sites are located above 3000 m in elevation, while less than 25% are below 1000 m. Additionally, the quantity of cultural heritage decreases with increasing distance from river systems. Slope also explains 20.09% of the spatial differentiation characteristics of cultural heritage along the railway.

In terms of social economy factors, GDP (X7) has the highest q value of 0.3721, indicating that the level of economic development is a key factor influencing the spatial pattern of cultural heritage. The economic development level of the Sichuan-Tibet Railway region directly affects the protection and utilization of cultural heritage. The stronger the regional economic strength, the more likely it is to attract population and resource aggregation, thereby giving rise to a rich and diverse array of cultural heritage. For example, cultural heritage sites in Chengdu and Lhasa account for 46.01% of the total. Additionally, population density (X6) and distance to historical cities (X4) also have significant impacts, with q values of 0.2360 and 0.1989, respectively. This suggests that population aggregation and the radiation effect of historical cities play important roles in the protection and inheritance of cultural heritage. Areas with high population density tend to have richer cultural heritage, while the distance to historical cities affects the dissemination and influence range of cultural heritage. In contrast, the explanatory power of distance to historical transportation routes (X5) is only 0.1133, indicating a weak driving force on the spatial differentiation of cultural heritage.

Historical and cultural factors play a decisive role in the formation of the spatial pattern of cultural heritage along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway. Among them, the q value of religious belief level (X10) is the highest at 0.9007, highlighting the core position of religion in the inheritance and development of cultural heritage in the region. Because some cultural heritage are important religious sites such as temples and pagodas, cultural heritage-intensive areas have been formed in space. At the same time, religious activities promote the intergenerational inheritance of art forms such as thangkas and murals and Tibetan architectural styles, and strengthen cultural communication through pilgrimage routes and festival ceremonies. In addition, the stability of the religious community provides long-term social support for the protection of cultural heritage, and ultimately shapes the cultural heritage space network with religion as the core. The religious beliefs in the Sichuan-Tibet region are diverse and profound, exerting a far-reaching impact on local culture and lifestyle. The q values of ethnic cultural background (X8) and historical settlement environment (X9) are also high at 0.5238 and 0.6163, respectively, further confirming the importance of historical and cultural factors in the formation of the spatial pattern of cultural heritage. The counties along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway have historically been important areas for economic trade and cultural exchanges between Han and Tibetan ethnic groups, with rich ethnic cultural backgrounds and unique historical settlement environments. These factors have formed many representative Chinese historical and cultural cities, towns, villages, and traditional villages, providing an overall cultural ecological environment for the protection of cultural heritage and jointly shaping the unique spatial pattern of cultural heritage in the region.

Analysis of multi-factor interaction driving mechanism. To explore the interactive effects of different factors on the spatial pattern of cultural heritage along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway, this study employs the Interaction Detector to further analyze the driving mechanisms of spatial differentiation of cultural heritage. The heat map reveals complex interrelationships and mechanisms among factors, showing that the combined effects of different factors enhance the explanatory power of the spatial pattern of cultural heritage, confirming that the spatial pattern of cultural heritage is the result of the combined effects of natural geographical constraints, socioeconomic factor guidance and cultural continuity (Fig. 9).

The interaction between natural geography, social economy and historical culture reveals the core logic of multi-factor synergy. First of all, the interaction between natural geography and historical culture is manifested in the fact that high-altitude areas strengthen the originality and continuity of religious culture due to geographical closure. For example, the interaction q value between elevation (X1) and religious belief level (X10) reaches 0.9536, and Tibetan Buddhist temples such as Seda Wuming Buddhist College, which are located at an altitude of more than 4000 m in Ganzi Prefecture, are both sheltered by the terrain and rely on religious activities to form settlement heritage. Because of the natural barrier, such areas limit the infiltration of external culture, but promote the high concentration of religious culture in space. Secondly, the interaction between social economy and natural geography is reflected in the breakthrough of natural constraints by the level of economic development. The interaction q value between GDP (X7) and elevation (X1) is 0.7301. Taking Lhasa as an example, through the investment in transportation infrastructure such as the extension of the Qinghai-Tibet Railway, the restrictions of high altitude on the development of cultural heritage are partially eliminated, and the spatial agglomeration of the cultural and tourism integration industry around the Potala Palace can be realized. Regions with strong economic strength can reshape the influence path of natural geographical conditions on the distribution of cultural heritage through technology investment and resource allocation. In addition, the interaction between social economy and historical culture is manifested as the “scale effect” of population aggregation on cultural inheritance. The interaction q value between population density (X6) and ethnic cultural heritage (X8) is 0.5801. As the starting point of the Sichuan-Tibet Railway, Chengdu relies on high-density population and diverse ethnic communities (such as Jinli Ancient Street) to form a “living heritage” protection model. Population agglomeration not only provides human and financial support for cultural heritage protection, but also accelerates the spatial diffusion of traditional handicrafts and festival culture through frequent cultural activities, forming a dynamic inheritance network.

Based on the above interaction, this study proposes a “three-force synergy” driving mechanism for the spatial pattern of cultural heritage along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway. Among them, natural base force refers to the initial distribution pattern of cultural heritage shaped by natural elements such as topography and water system by limiting the scope of human activities (such as the concentration of religious heritage in high altitude areas). Economic boost force refers to the regional economic level and population agglomeration through resource supply and spatial transformation, breaking through natural constraints and activating the modern use of cultural heritage (such as Lhasa Cultural and Tourism Economic Belt). Cultural continuity force refers to the fact that religious beliefs and national traditions maintain the authenticity and spiritual connotation of cultural heritage through intergenerational transmission and symbol solidification (such as the network of Tibetan Buddhism). The three form a positive feedback loop through nonlinear superposition: for example, religious activities (cultural continuity force) attract the pilgrim population (economic boost force), and then promote the construction of transportation facilities (natural base force improvement), and ultimately expand the distribution of cultural heritage.

Discussion

Firstly, this research mainly has the following theoretical value:

-

(1)

The existing literature mostly focuses on the static spatial pattern of linear cultural heritage. For example, Zhang et al. revealed the spatial agglomeration characteristics of China ‘s border cultural heritage through kernel density analysis, but did not involve the law of spatial and temporal evolution27. Similarly, although Cao et al. quantified the spatial and temporal distribution of traditional Chinese medicine, they lacked a discussion on the dynamics of local spatial autocorrelation25. This study introduces LISA spatial-temporal transition and network analysis, and finds that the spatial pattern of cultural heritage along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway presents a quasi-periodic feature of weak agglomeration-strong agglomeration-weak agglomeration, and 62.5% of the counties have spatial autocorrelation inertia, revealing the long-term impact of historical path dependence on the distribution of cultural heritage. This conclusion is complementary to the dynamic adaptability theory of modern transportation heritage proposed by Ruiz et al., revealing the temporal and spatial inertia characteristics of linear heritage under the constraints of natural base1. In addition, the application of OPGD significantly improves the interpretation accuracy of the driving mechanism, which is more scientific than the traditional GD.

-

(2)

Existing studies generally emphasize the dominance of natural and socioeconomic factors. For example, Yuan et al. pointed out that the heritage distribution of the Yellow River National Cultural Park is driven by water system and population density28, while Shen et al. found that national cultural heritage is significantly related to economic level48. However, this study confirms that the level of religious belief is the strongest explanatory factor for the distribution of cultural heritage along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway, which is partially consistent with Astor’s research on the politicization of religious heritage17, but it also highlights the unique influence of Tibetan Buddhism on the originality and continuity of plateau cultural heritage. In addition, the study also found that the interaction between the natural base and religious culture (such as high altitude to strengthen religious heritage agglomeration) provides a regional empirical evidence for Harvey’s “landscape heritage trajectory theory”8.

-

(3)

Existing studies pay more attention to traditional routes such as ancient post roads and canals. For example, Li et al. discussed the ecological security and heritage activation of the Straight Road of the Qin Dynasty3, while Zhang et al. analyzed the tourism value of the Silk Road5. In contrast, this paper takes the modern railway (Sichuan-Tibet Railway) as the research object, and finds that it is highly overlapped with the Tea-Horse Road in space, and a strong positive correlation is formed at both ends of the railway. This finding confirms Caton’s hypothesis of “heritageization of traffic corridors”20 and complements Denstadli’s model of “perceived quality of landscape routes” with empirical evidence of the cultural heritage dimension6.

Secondly, this study draws the following management implications:

-

(1)

The spatial overlap rate between the Sichuan-Tibet Railway and the Tea-Horse Ancient Road is high. It can rely on the advantages of railway connection to integrate cultural heritage resources along the route and create a Sino-Tibetan cultural integration corridor. Priority should be given to setting up heritage protection centers in cultural agglomeration areas such as Chengdu and Lhasa, and coordinating the restoration of core heritage nodes such as ancient post stations and Tibetan Buddhist temples. In the middle ecologically sensitive areas (Litang to Changdu), a cultural-ecological compound reserve is established to limit large-scale development, restore the ancient post road landscape through digital modeling, and use AR technology to create virtual tour routes to reduce physical intervention. In addition, the counties along the joint set up a cross-administrative cultural heritage management alliance to formulate unified protection standards and avoid fragmentation of protection due to administrative division.

-

(2)

Given the symbiotic relationship between cultural heritage and the natural environment on the Tibetan Plateau, a living cultural ecosystem framework must be developed. First, in traditional villages (Danba Tibetan Villages), implement in-situ intangible cultural heritage conservation by embedding practices like Thangka painting and Tibetan medicinal processing into daily community life. A resident ICH practitioner program can ensure intergenerational transmission of these traditions. Second, in high-altitude religious heritage areas (Larung Gar Buddhist Academy), execute ecological restoration projects using native vegetation to rehabilitate exposed slopes, while standardizing pilgrimage routes to reduce human-induced damage to fragile terrains. This dual approach synchronizes cultural continuity with ecological governance to preserve heritage integrity.

-

(3)

Capitalizing on the railway’s connectivity, develop immersive tourism products such as “themed carriage exhibitions” and “heritage station hubs”, transforming trains into mobile cultural spaces that dynamically narrate ICH stories along the route. In high-traffic destinations, promote reservation-based in-depth tourism featuring niche experiences like pilgrimage trail trekking and Tibetan homestead visits to alleviate overcrowding. Support community-led cultural cooperatives to market region-specific products (highland barley-themed cultural goods, yak wool handicrafts), directing profits toward heritage restoration. Concurrently, establish a tourism feedback fund that allocates fixed percentages of ticket revenues to ICH practitioner training, creating a self-sustaining tourism-nurtures-heritage cycle.

In addition, this study also has the following shortcomings and prospects: Firstly, the research data mainly comes from the census data of cultural relics, and it is inevitable that the data is incomplete. For example, it is difficult to accurately locate the birthplace of some intangible cultural heritage, which may affect the accuracy of the research results. Secondly, the time span of this study is limited, and it fails to cover the spatial and temporal evolution mechanism of cultural heritage in a longer historical period. On the method, although the OPGD model can be optimized according to the discrete parameter combination corresponding to the highest explanatory degree of the variable, its ability to deal with nonlinear relationships is limited, and it may not fully reveal the complex interactions between all factors. Based on the limitations of this study, future research can be expanded from the following aspects. Firstly, we should further improve the cultural heritage database, strengthen the investigation and recording of intangible cultural heritage, and improve the accuracy and integrity of the data. Secondly, future research should strengthen exchanges with geological and archeological experts to identify the main factors affecting the spatial pattern of ancient cultural heritage. On this basis, the long-term evolution law of cultural heritage can be analyzed in depth by combining longer time series data. In terms of methods, it is suggested to introduce machine learning algorithms, to further explore the complex relationship between influencing factors and provide more scientific decision support for cultural heritage protection.

Finally, this study systematically analyzes the spatial-temporal pattern and evolution characteristics of cultural heritage in more than 30 counties along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway and explores the key factors influencing its spatial distribution. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

Spatial-Temporal Evolution Characteristics of Cultural Heritage: The quantity and distribution of cultural heritage in counties along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway have shown significant dynamic changes over time. From prehistory to modern times, the number of cultural heritage sites has continuously increased. The global Moran’s I index indicates a significant positive spatial autocorrelation, with a quasi-periodic pattern of weak agglomeration-strong agglomeration-weak agglomeration, reaching the strongest clustering state during the Qin-Han-Sui-Tang to Song-Yuan periods. Further analysis using LISA time path and spatial-temporal transition reveals the dynamic nature and transfer characteristics of the local spatial structure of cultural heritage. Some counties have experienced significant changes in the quantity of cultural heritage during different periods, while most counties show strong stability in spatial autocorrelation. Additionally, the spatial pattern of cultural heritage quantities along the railway shows collaborative development at both ends, dominated by strong positive correlation, while the central section is a differentiated development area, mainly characterized by weak negative correlation.

-

(2)

Analysis of Influencing Factors on Spatial Pattern: Using the OPGD, this study identifies the mechanisms by which natural geography, social economy, and historical culture influence the spatial pattern of cultural heritage. The results show that religious belief level, historical settlement environment, economic development level (GDP), and population density are key factors influencing the spatial pattern of cultural heritage. Among them, the religious belief level has the strongest explanatory power for cultural heritage distribution, indicating the core position of religious culture in the formation and inheritance of cultural heritage along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway. Moreover, the interaction between historical and cultural factors and natural geography and social economy factors significantly enhances the explanatory power of the spatial pattern of cultural heritage, indicating that the distribution of regional cultural heritage is the result of the combined effects of multiple factors.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ruiz, R., Rodríguez, J. & Coronado, J. M. Modern roads as UNESCO World Heritage sites: framework and proposals. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 23, 1–13 (2017).

Zhang, S.-Y. et al. Tourism value assessment of linear cultural heritage: the case of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal in China. Curr. Issue Tour. 26, 47–69 (2023).

Li, H., Zhang, T., Cao, X.-S. & Yao, L.-L. Active Utilization of Linear Cultural Heritage Based on Regional Ecological Security Pattern along the Straight Road (Zhidao) of the Qin Dynasty in Shaanxi Province, China. Land 12, 1361 (2023).

Jiang, A.-H. et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics and driving factors of vegetation coverage around linear cultural heritage: a case study of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal. J. Environ. Manag. 349, 119431 (2024).

Zhang, S.-Y., Liu, J.-M., Zhu, H. & Zhang, X.-J. Characteristics and tourism utilization of linear cultural heritage: a statistical analysis on the World Heritage List. J. Chin. Ecotourium11, 203–216 (2021).

Denstadli, J. M. & Jacobsen, J. K. S. The long and winding roads: perceived quality of scenic tourism routes. Tour. Manag. 32, 780–789 (2011).

Sugio, K. A Consolidation on the Definition of the Setting and Management/Protection Measures for Cultural Routes (World Publishing Corporation, 2005).

Harvey, D. Landscape and heritage: trajectories and consequences. Landsc. Res. 40, 911–924 (2015).

Cottle, C. The South Carolina National Heritage Corridor taps heritage tourism market. Forum J. 17, 4650 (2003).

Lovelock, B. & Boyd, S. Impediments to a cross-border collaborative model of destination management in the catlins, New Zealand. Tour. Geogr. 8, 143–161 (2006).

Martorell, C. The transmision of the spirit of the place in the living cultural routes: the Route of Santiago de Compostela as case study. Stren Mate 45, 82–92 (2017).

Shan, J.-X. Preliminary discussion on large-scale linear cultural heritage protection: breakthrough and pressure. Cult. Relics South. China 3, 1–5 (2006).

Zhang, H., Wang, Y.-T., Qi, Y., Chen, S.-W. & Zhang, Z.-K. Assessment of Yellow River region cultural heritage value and corridor construction across urban scales: a case study in Shaanxi, China. Sustainability 16, 1004 (2024).

He, D., Hu, J.-C. & Zhang, J. Assessment of sustainable development suitability in linear cultural heritage—a case of Beijing great wall cultural belt. Land 12, 1761 (2023).

Li, F., Ma, J.-G. & Liu, X.-H. Residents’ perceived and expected value of linear cultural heritage: the example of the Yunnan-Vietnam railway. Trop. Geogr. 41, 93–103 (2021).

Yue, F.-T., Li, X.-Q., Huang, Q. & Li, D. A framework for the construction of a heritage corridor system: a case study of the Shu Road in China. Remote Sens. 15, 4650 (2023).

Astor, A., Burchardt, M. & Griera, M. The politics of religious heritage: framing claims to religion as culture in Spain. J. Sci. Study Relig. 56, 126–142 (2017).

Payne, A. A. & Hurt, D. A. Narratives of the mother road: geographic themes along route 66. Geogr. Rev. 105, 283–303 (2015).

Qin, X.-C., Cui, S.-N. & Liu, S. Linking ecology and service function in scenic road landscape planning: a spatial analysis approach. J. Test. Eval. 46, 1297–1312 (2018).

Caton, K. & Santos, C. A. Heritage tourism on route 66: deconstructing nostalgia. J. Travel Res. 45, 371–386 (2007).

Makkay, K., Pick, F. R. & Gillespie, L. Predicting diversity versus community composition of aquatic plants at the river scale. Aquat. Bot. 88, 338–346 (2008).

Tomic, N. The potential of Lazar Canyon (Serbia) as a geotourism destination: inventory and evaluation. Geogr. Pannonica 13, 103–112 (2011).

Bozis, S. & Tomic, N. Developing the cultural route evaluation model (CREM) and its application on the Trail of Roman Emperors, Serbia. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 17, 23–35 (2016).

Campolo, D., Bombino, G. & Meduri, T. Cultural landscape and cultural routes: infrastructure role and indigenous knowledge for a sustainable development of inland areas. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 223, 576–582 (2016).

Cao, K.-R., Liu, Y., Cao, Y.-H., Wang, J.-W. & Tian, Y.-G. Construction and characteristic analysis of landscape gene maps of traditional villages along ancient Qin-Shu roads, Western China. Herit. Sci. 12, 37 (2024).

Gan, X.-J., Wang, H. & Ye, L. An analysis of the spatiotemporal evolution of traditional medicine in China using point-area representation. Npj Herit. Sci. 13, 110 (2025).

Zhang, S.-R., Chi, L., Zhang, T.-Y. & Ju, H.-R. Spatial pattern and influencing factors of land border cultural heritage in China. Herit. Sci. 11, 187 (2023).

Yuan, D., Wu, R.-H., Li, D., Zhu, L. & Pan, Y.-G. Spatial patterns characteristics and influencing factors of cultural resources in the Yellow River National Cultural Park, China. Sustainability 15, 6563 (2023).

Zhang, Z.-W., Li, Q. & Hu, S.-X. Intangible cultural heritage in the Yellow River Basin: its spatial-temporal distribution characteristics and diferentiation causes. Sustainability 14, 11073 (2022).

Liang, Y.-Q., Yang, R.-X., Wang, P., Yang, A.-L. & Chen, G.-L. A quantitative description of the spatial-temporal distribution and evolution pattern of world cultural heritage. Herit. Sci. 9, 1–14 (2021).

Xu, X.-Y., Sun, X.-H. & Liu, J.-P. Spatial-temporal characteristics and determinants of World heritages in Italy. World Reg. Stud. 28, 187–196 (2019).

Pang, L. & Wu, L.-N. Distribution characteristics and influencing factors of intangible cultural heritage in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei. Herit. Sci. 11, 19 (2023).

Dong, B.-L., Bai, K., Sun, X.-L., Wang, M.-T. & Liu, Y. Spatial distribution and tourism competition of intangible cultural heritage: take Guizhou, China as an example. Herit. Sci. 11, 64 (2023).

Liu, S., Ge, J., Bai, M., Yao, M. & Zhu, Z.-N. Uncovering the factors influencing the vitality of traditional villages using POI (point of interest) data: a study of 148 villages in Lishui, China. Herit. Sci. 11, 123 (2023).

Yang, Y.-H., He, J.-X., Zhang, X.-H. & Rui, Y. Multi-scale spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of Chinese vernacular culture. J. N. W. Uni(Nat. Sci. Edi). 53, 529–540 (2023).

Fu, J., Zhou, J.-L. & Deng, Y.-Y. Heritage values of ancient vernacular residences in traditional villages in Western Hunan, China: Spatial patterns and influencing factors. Build Environ. 188, 107473 (2021).

Li, M.-M., Wu, B.-H. & Cai, L.-P. Tourism development of world heritage sites in China: a geographic perspective. Tour. Manag. 29, 308–319 (2008).

Zhang, Z.-W., Li, Q. & Hu, S.-X. Intangible cultural heritage in the Yellow River Basin: its spatial-temporal distribution characteristics and differentiation causes. Sustainability 14, 11073 (2022).

Feng, Z.-M. Study on Framework of the Protection and GIS Technology Application of the Sichuan-Tibet “Tea Horse Road” Cultural Routes Heritage. Doctoral dissertation, Master thesis of Chongqing University. (2016).

Yang, C.-Y. et al. Spatial-temporal variation characteristics of vegetation coverage along Sichuan-Tibet railway. J. Arid Land 35, 174–182 (2021).

Moran, P. A. The interpretation of statistical maps. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 10, 243–251 (1948).

Rey, S. J. Spatial empirics for economic growth and convergence. Geogr. Anal. 33, 195–214 (2010).

Ye, X. Y. & Rey, S. A framework for exploratory space-time analysis of economic data. Ann. Reg. Sci. 50, 315–339 (2013).

Rey, S. J. & Janikas, M. V. STARS: space-time analysis of regional systems. Geogr. Anal. 38, 67–86 (2006).

Elhorst, J. P. Matlab software for spatial panels. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 37, 389–405 (2014).

Song, Y.-Z., Wang, J.-F., Ge, Y. & Xu, C.-D. An optimal parameters-based geographical detector model enhances geographic characteristics of explanatory variables for spatial heterogeneity analysis: cases with different types of spatial data. GISci Remote Sens. 57, 593–610 (2020).

Wang, J.-F. & Xu, C.-D. Geodetector: principle and prospective. Acta Geogr. Sin. 72, 116–134 (2017).

Shen, W. et al. Spatial pattern and its influencing factors of national-level cultural heritage in China. Herit. Sci. 12, 1–17 (2024).

Kummu, M., Moel, H. D., Ward, P. J. & Varis, O. How close do we live to water? A global analysis of population distance to freshwater bodies. PLoS ONE 6, e20578 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: U24A20583). The authors would like to thank the research group for the financial support and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.C. and L.Z. briefly introduced the background and reviewed all the published papers. L.C., L.Z., and S.Z. collected relevant data and made tables for explanation. L.C. and L.Z. analyze the spatial pattern of county-level cultural heritage along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway in China. L.C., S.Z., and T.Z. summarized the factors affecting the spatial distribution of county-level cultural heritage along the Sichuan-Tibet Railway in China and proposed suggestions for the protection and development of the heritage resources. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chi, L., Zhong, L., Zhang, S. et al. Spatial-temporal pattern of cultural heritage along the Sichuan Tibet railway and influencing factors. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 301 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01849-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01849-x