Abstract

Huashan Rock Art, located in Guangxi, China, reflects the social, economic, cultural, and artistic aspects of the local ancestors and is included in the World Cultural Heritage list. However, surface cracking and pigment layer detachment have severely affected its value. This study employed Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), micro X-ray fluorescence (μ-XRF), micro-Raman, and X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) to analyze the micro-characteristics of the rock art’s surface. Results show a three-layer surface structure: calcium sulfate, pigment layer, and rock layer. Calcium sulfate is partially embedded into the pigment layer, making it difficult to remove. The distribution of calcium sulfate indicates that sulfur (S) mainly comes from the external environment. XRD analysis reveals that the phase changes of calcium sulfate play a significant role in rock art deterioration. This study provides a new microscopic perspective for pigment layer research and offers a scientific reference for the protection and study of rock art heritage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rock art is one of the types of cultural heritage that uses rocks as a medium. Before the emergence of written language, early humans recorded their production, life, and spiritual world through this form of imagery. To date, rock art relics have been discovered on five major tectonic plates in the world, providing intuitive materials for studying the aspects of human societies in different regions and historical periods1,2,3. Unfortunately, over millennia, these precious cultural heritages, often exposed to open-air environments, have been subjected to a range of natural and human-induced factors, resulting in their deterioration or even disappearance. Although extensive research and published work has been conducted on the physical conditions and pigment characteristics of rock art sites globally4,5, studies focusing on the mechanisms of their surface pigment deterioration remain limited. Such research is crucial for the effective conservation and long-term preservation of this irreplaceable cultural heritage.

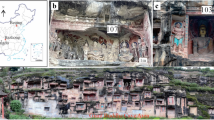

The Huashan Rock Art, located in Guangxi, China, is distributed along the Zuojiang River basin, and was inscribed as a World Cultural Heritage site by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization in 2016, representing one of the most significant prehistoric cultural heritages in southwestern China. The rock paintings are all painted in red, and the main content includes squatting human figures, abstract animals, and symbols (Fig. 1c). Published studies indicate that plant sap was used as a binder to mix with iron-rich red mineral pigments in the creation of the Huashan rock paintings6,7. According to the C14 dating results, the Huashan Rock Art was created approximately 2200–2400 years ago6. This area belongs to the subtropical humid monsoon climate zone, characterized by high temperatures, ample sunshine, abundant but uneven rainfall, a long summer without winter, and a continuous spring and autumn with a long frost-free period8. In terms of topography, the Huashan Rock Art cultural heritage protection area is situated in a valley region, with high mountains and deep ravines on both sides of the river, most of which are over 500 m high. The rock art is distributed on the cliffs along both sides of the river, as shown in Fig. 1a, b.

Despite being painted on durable limestone rock, however, these valuable rock arts have not been immune to deterioration over time, especially in the surface pigment layer. Cracking and flaking of the rock surface, along with pigments fading, are prominent issues affecting the Huashan Rock Art (Fig. 1d, e), and the ongoing detachment and damage of the surface continue to threaten the preservation of the value of this cultural heritage. As early as 2005, scholars had already investigated the issues of fading and peeling affecting the Huashan rock paintings9. Notably, the weathering mechanism of these petroglyphs’ surface layers has not been fully understood until now, with limited literature available on this topic. In early studies, GUO et al.10,11,12 proposed that the roles of water and biological factors are two major contributors to the weathering damage of the Huashan rock paintings. Then in the survey research published in 2009, the temperature difference stress on the rock surface and the physical weathering caused by repeated wetting and drying were considered the main reasons for the flaking disease13. Furthermore, SUN et al.14 tested the thermal expansion rate of the Huashan rock and proposed that the anisotropy in the thermal expansion process of the calcite carrier might cause damage to the rock art. In recent years, research by Chen et al.15 also found that changes in the rock’s temperature and humidity could intensify the cracking process of the rock surface at Huashan. Despite these studies, comprehensive and in-depth research into the weathering process affecting the surface pigment layers of this rock art site, especially at a microscopic level, is still insufficient (Fig. 2).

In recent decades, modern characterization techniques have been widely employed to analyze the microstructures and physicochemical properties of rock art surfaces16,17,18,19,20. These methods can generally be grouped into three categories: spectroscopy, microscopy, and diffraction techniques. Among these, micro-Raman spectroscopy has demonstrated exceptional performance in studying the micro-characteristics of rock art due to its non-destructive nature and ability to provide spatial resolution of different structures within a sample21,22. Similarly, micro X-ray fluorescence (μ-XRF), compared to traditional X-ray fluorescence (XRF), can quickly obtain elemental information over a larger area and shows excellent potential for non-destructive testing and analysis of rock art and other cultural heritage samples23,24. In addition, Scanning Electron Microscopy - Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) and X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) are two commonly used analytical techniques. SEM-EDS provides simultaneous information on the surface morphology and elemental distribution of a sample, while XRD can effectively aid in identifying the mineral composition of pigments and rock substrates. Although these techniques have demonstrated their advantages in the field of cultural heritage conservation, the systematic application in Huashan rock paintings has not yet been reported. To elucidate the microstructural characteristics of the surface layer, particularly the pigment layer, of the Huashan Rock Art and to deepen the understanding of the mechanisms behind its deterioration, this paper employs a comprehensive set of testing methods including μ-XRF, Micro-Raman, SEM, and XRD. These methods are used to characterize the microstructure of the Huashan Rock Art samples from two dimensions: different areas on the surface and different depths within the sample. The analysis of the structural features and deterioration mechanisms aims to provide a reference for further research on rock art conservation and the development of effective protective measures.

Methods

Samples

Huashan Rock Art is both a World Cultural Heritage site and a National Key Cultural Relics Protection Unit in China, destructive sampling does not be permitted. Hence, all samples used in this study are fragments of rock art that have fallen off the cliffs gathered by the Guangxi Institute of Cultural Relics Protection and Archeology during routine work. They were collected from various locations across hundreds of meters of the cliff at Huashan, ensuring representativeness. Optical photographs and corresponding descriptions of the samples are presented in Table 1. In the series of tests conducted on the samples, distinctions were made between the front and back sides. The side with red pigment is referred to as the front side of the sample, while the side closer to the mountain, which is entirely rock, is designated as the back side of the sample. Except for the sputter-coating with gold prior to SEM analysis, no other special pretreatment was performed on the samples.

Microstructural information test

SEM-EDS and μ-XRF were used to test the micromorphology and elemental distribution of different areas on the sample surface. The desktop scanning electron microscope model is Phenom XL G2, and EDS testing was conducted under an acceleration voltage of 15 kV. The Bruker M4 TORNADO PLUS micro-area X-ray fluorescence spectrometer has a maximum output power of 30 W, a maximum tube voltage of 50 kV, and a maximum tube current of 0.6 mA.

The BWTEK I-Raman was used to test the structural information at different depths within the sample. The instrument has a resolution of 4 cm–1, with a spectral range of 65–3200 cm–1, and a ×50 long-focus objective lens was used during testing with an excitation wavelength of 780 nm. In the test, the exposure time was 10 s, and the number of cycles for data acquisition was 3 times.

Mineral composition test

The mineral composition of the sample was tested using the Rigaku SmartLab SE X-ray diffractometer. The maximum output power of the device’s X-ray generator is 3 kW, with a maximum tube voltage of 60 kV and a maximum tube current of 60 mA.

Results

Microscopic characteristics of different areas on the sample surface

SEM tests were conducted on both the front and back sides of the sample S1–S4. As can be seen from the scanning electron microscope images, the structure of the front side (F) of the samples are more porous and looser than the back side, with particle sizes ranging from a few to several tens of micrometers. The EDS results show that the main elemental composition of the sample’s front side is S, Ca, and O, with a relatively high content of S. The back side (B) of the samples have a denser structure, with the main elements being Ca, O, and C, and no sulfur element was detected by EDS. This indicates that the front side of the samples have a loose and porous sulfur-containing coating, and within the testing depth range of EDS, the special elemental signals belonging to the pigment were not detected.

Furthermore, to observe the distribution of elements on the sample surface at a more macroscopic scale, μ-XRF was used to test different surfaces of the sample S1, and the results are shown in Fig. 3. The test area on the front side of the sample includes two different states: the left side is the area where the rock substrate is exposed, and the right side is covered with red pigment. Figure 3a1-4 is the optical photos of the test area on the front side of the sample and the distribution of the main elements. The results show that there is S element coverage on different areas of the sample surface, with the percentage of S element in the pigment-peeled area higher than that in the pigment-covered area, which indicates that calcium sulfate deposition occurred after the pigment layer was applied and continued to enrich even after the pigment had flaked off. The distribution of Fe element is basically consistent with the pigmented area, and the distribution percentage of Ca element shows no significant difference in different areas. Figure 3b1-3 is the optical photos of the test area on the back side of the sample and the distribution of the main elements. The S element is only sparsely distributed, mainly consisting of Ca element, and no Fe element signal is detected on the back side.

At the same time, four test points were selected at different positions on the sample surface, and elemental content tests were conducted at each point. Table 2 lists the main elemental composition of each test point. The S element content in Dot 1 and Dot 2 on the front side of the sample is relatively high, at 26.44% and 17.79%, respectively, with the pigment-peeled area significantly higher than the unpigmented area, reflects that the enrichment of sulfur may have a certain impact on the peeling off of rock painting pigment layer. The S element content in Dot 3 and Dot 4 on the back side of the sample is lower, not exceeding 2%. The test results all reflect that the sulfur element content on the front side of the sample is much higher than on the back side, indicating that the surface sulfur element mainly comes from the external environment, and the amount produced by the dissolution of S from within the rock is relatively small.

The same differences were consistently observed across the XRF results for samples S2 to S4. As illustrated in Table 3, the front side of each sample exhibited an S element content of approximately 20%, in contrast to the back sides, where the highest S content reached merely 1.25%. Notably, the front sides of samples S2–S4 are mostly covered with red pigment, with only minor areas of loss, so the front sides show higher Fe element content, while no Fe element was detected on the back sides. In line with the findings for S1, the back sides of these samples displayed elevated Mg levels relative to the front sides. This pattern may arise from the presence of front-side pigment and other surface layers, which could interfere with the detection of Mg element. Alternatively, it might indicate Mg element depletion due to surface weathering processes. These results further indicate that there is an S-bearing surface structure on the rock paintings in addition to the pigment layer, which requires further analysis with more techniques.

Microscopic characteristics at different depths within the sample

To further reveal the microscopic structure of the sample’s surface, Micro-Raman spectroscopy was used for compositional analysis. Due to the sample’s flatness potentially interfering with testing, the analysis was performed on sample S1.

Firstly, signals from different depths of the sample surface were obtained by adjusting the focal depth. From the microphotograph of the sample’s front side in Fig. 4a1, it can be seen that the red pigment material does not completely cover the rock surface, with some areas missing. In the microphotograph of the sample’s back side (Fig. 4b1), white crystals and the rock substrate can be observed, indicating that the underlying limestone crystals have good crystallinity. In Fig. 4a2, F1-F3 represent the changes in Raman spectra obtained from the pigmented area of the sample’s front side as the focal depth increases. By comparing with literature data, it is known that the peaks at 414 cm–1, 492 cm–1, 671 cm–1, 1007 cm–1, and 1135 cm–1 are characteristic peaks of calcium sulfate25, while the peaks at 295 cm–1 and 413 cm–1, 606 cm–1 are characteristic peaks of α-Fe2O326. Combining the elemental analysis with the Raman test results of Fig. 4a2, it can be preliminarily concluded that the surface covering of the sample is calcium sulfate, and the red coloring mineral in the pigment is α-Fe2O3. The Raman curve of the sample’s back side, Fig. 4b2, shows characteristic peaks at 280 cm–1 and 1086 cm–1, which correspond to calcium carbonate27, indicating that the main component of the rock carrier of the rock art is calcium carbonate.

It is worth noting that there are strong signals of calcium sulfate at different testing depths in Fig. 4F1-3. The signals obtained from the surface layer F1 are all calcium sulfate. After increasing the depth, hematite is detected in F2, but with weak intensity. In F3, there are signals belonging to the rock substrate’s calcium carbonate, as well as calcium sulfate and hematite, which reflects that the thickness of the pigment layer is extremely thin, easily penetrated, and calcium sulfate may have penetrated to the bottom of the pigment layer and combined directly with the rock.

Then, Micro-Raman tests were also conducted at various positions on the cross-section of the sample, and the results are shown in Fig. 5b1-4. From the ×70 magnified photo in Fig. 5a1, it can be clearly seen that the area less than 100 μm on the sample surface is composed of three structural parts: the surface layer, the pigment layer, and the rock layer. The thickness of the surface layer is not uniformly distributed at different positions, and the pigment layer is extremely thin. The scanning electron microscope results of the cross-section Fig. 5a2 show that there is a certain difference in the density between the surface layer and the internal layers, but the contrast of the pigment layer under the scanning electron microscope is limited and the thickness is thin.

Under the optical microscope, the color differences of the three different components of the sample are well distinguished. As can be seen from Fig. 5b1, there is a phenomenon where the surface covering invades the pigment layer, which corresponds to the results in Fig. 4 where calcium sulfate signals were detected at different focal depths. At the same time, the Raman test results at different positions of the sample cross-section in Fig. 5b2-4 correspond well with the characteristic peaks of different components in Fig. 4, further verifying the composition at different depths within the sample.

Weathering mechanism

In order to elucidate the mechanism of rock art surface deterioration from a microscopic perspective, XRD was used to analyze the mineral phase composition of the front and back surfaces of the sample. As can be seen from Fig. 6b, the back of the sample is mainly composed of calcium carbonate. According to published research, calcareous rocks are susceptible to transformation into sulfates under the influence of acidic environments. This transformation includes two different pathways: dry deposition and acid rain, as shown in Eq. (1) and Eq. (2), respectively28. The XRD results of the front side of the sample detected two different phases of calcium sulfate, dihydrate calcium sulfate (commonly known as gypsum, CaSO4·2H2O) and anhydrous calcium sulfate (commonly known as anhydrite, CaSO4). Dihydrate calcium sulfate belongs to the monoclinic crystal system, with water molecules located between the double-layer structures formed by SO42- tetrahedra and Ca2+ linkages. Anhydrous calcium sulfate, on the other hand, belongs to the orthorhombic crystal system and does not contain crystalline water in its structure. The crystal structure of anhydrous calcium sulfate is more compact, with a higher density, and it readily absorbs moisture from the air to transform into dihydrate calcium sulfate, which has a lower density, under conditions of high environmental humidity (Eq. (3))29. The climate in the Huashan area is sufficient to meet this condition.

The impact of calcium sulfate coverage on the rock art is multi-dimensional, as shown in Fig. 7. On one hand, the calcium sulfate that invades the pigment layer undergoes phase changes, and the expansion of crystal volume and further growth generate crystallization pressure that can cause damage to the rock art’s pigment layer. When calcium sulfate is abundant, the accumulation of its crystallization process can cause the pigment layer and the surface rock to detach from the substrate, which is one of the causes of flaking diseases. On the other hand, the calcium sulfate deposited on the surface forms a crust of a certain thickness, preventing the pigment layer from direct contact with rainwater, surface runoff, and dust, reducing its fading due to external environmental factors, and thus providing a certain level of protection. Additionally, the calcium sulfate covering on the surface is tightly bonded with the pigment layer, making it difficult to remove the covering by general physical methods.

As an outdoor, large-scale, and immovable cultural heritage, rock paintings are subject to weathering influenced by various factors, such as pigment, binders and salts. Among these, the role of salts such as calcium sulfate in the porous medium of rocks has long been a focus of attention30. Notably, over the past decade, due to the acceleration of industrialization, the impact of air pollution on cultural heritage has gradually garnered increasing attention from researchers31,32. Similarly, at the Huashan Rock Painting site, enhanced acid deposition in the atmosphere is also one of the significant sources of sulfur elements on the rock painting surface. Figure 8 presents temperature and humidity data recorded by the environmental monitoring station installed at the Huashan Rock Painting from August 2024 to March 2025. The maximum temperature at this location is approximately 33 °C, while the minimum temperature remains above 15 °C, and the relative humidity is consistently maintained above 90%. Under these environmental conditions, the conversion of anhydrite to gypsum occurs very easily33. Additionally, biological factors play an important role in the weathering of rock paintings and other stone cultural relics. Research by Prieto et al.18 indicates that the action of organisms such as lichens can also lead to the formation of gypsum. Therefore, the occurrence and development of weathering-related damage in rock paintings are the result of multiple factors acting in concert, and their conservation and management require more systematic research.

Discussion

This study aims to deepen the understanding of the mechanisms behind the deterioration of the surface diseases of the Huashan Rock Art by conducting a comprehensive analysis of the microstructure of the sample surface using various non-destructive analytical methods. Under this objective, the integrated use and correlation analysis of multiple testing techniques offer unique insights into the microstructure of the pigment layer and the weathering mechanisms of the rock paintings. Notably, the micromorphology and elemental analysis of different areas on the sample surface show that there is a layer of calcium sulfate covering the outer surface of the Huashan Rock Art samples, and there is a significant difference in sulfur content between the inner and outer surfaces. Furthermore, the elemental distribution and micro-characteristics at different depths within the sample indicate that the surface covering is tightly bonded with the pigment layer, and some of it has invaded into the pigment layer and combined with the rock layer. On this basis, when the pigment layer has a high content of calcium sulfate, its phase changes and the resulting crystallization pressure can lead to the occurrence of surface diseases.

Furthermore, a deeper understanding of the weathering mechanisms contributes to developing more effective conservation strategies. The tight bond between calcium sulfate and the pigment layer on the surface of the rock art makes it difficult to remove the calcium sulfate layer without damaging the pigment using conventional physical methods. However, it is noteworthy that a small amount of enriched calcium sulfate layer can also reduce the direct contact between the pigment and the external environment, which may have certain beneficial effects on the preservation of the rock art. In-depth analysis of the three-layer composite structure of calcium sulfate-pigment layer (α-Fe2O3)-rock layer in Huashan Rock Art not only helps to elucidate the mechanisms of rock art deterioration but also provides a scientific basis for the conservation of this world cultural heritage.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Jalandoni, A., Taçon, P. & Haubt, R. A systematic quantitative literature review of Southeast Asian and Micronesian Rock Art. Adv. Archaeol. Pract. 7, 423–434 (2019).

Mcclure, S. B., Balaguer, L. M. & Auban, J. B. Neolithic rock art in context: Landscape history and the transition to agriculture in Mediterranean Spain. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 27, 326–337 (2008).

Smith, B. W. & Ouzman, S. Taking stock - Identifying Khoekhoen herder rock art in Southern Africa. Curr. Anthropol. 45, 499–526 (2004).

Gomes, H. et al. Pigment in western iberian schematic rock art: an analytical approach. Mediterr. Archaeol. Ar. 15, 163–175 (2015).

Stuart, B. H. & Thomas, P. S. Pigment characterisation in Australian rock art: a review of modern instrumental methods of analysis. Herit. Sci. 5, 1–6 (2017).

Kuang, G. et al. Early analysis of pigment synthesis and mechanism of the Zuojiang Huashan Rock Paintings. Chin. Cult. Herit. 4, 82–85 (2016).

Sun, Y., Wang, Z. & Wei, S. Analysis of binder materials of pigments in Huashan Rock Art, Ningming, Guangxi. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 24, 38–43 (2012).

Huang, X. et al. Climate changes in temperature and precipitation in Guangxi over the past 50 years. Guangxi Meteor 4, 9–11 (2005).

Guo H., et al. Prevention and control strategies for pigment fading in the Huashan Rock Paintings of Guangxi. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 4, 7-14+67 (2005).

Guo, H. et al. Mechanisms and prevention strategies for biological weathering of Rocks in the Huashan Rock Paintings of Guangxi. Chin. Cult. Relics Sci. Res. 2, 64–69 (2007).

Guo H. et al. Environmental Pollution and Its Preventive Measures for the Huashan Rock Paintings of Guangxi; Proceedings of the 2005 Yungang International Academic Symposium Datong, Shanxi, China (2005).

Guo, H. et al. The role of water in weathering damage and prevention strategies for the Huashan Rock Paintings of Guangxi. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 2, 5–13 (2007).

Zhang, B. Investigation of rock painting diseases in the Huashan Rock Paintings of Ningming, Guangxi. Chin. Cult. Relics Sci. Res. 3, 63–66 (2009).

Sun, Y. & Wang, Z. Analysis of pigment flaking and fading in the Huashan Rock Paintings of Guangxi. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 23, 13–17 (2011).

Chen, J. et al. Analysis of the cracking mechanism in the surface rock of the Huashan Rock Paintings in Ningming, Guangxi. Fudan J. Nat. Sci. Ed. 60, 157–165 (2021).

Domingo, I. & Chieli, A. Characterizing the pigments and paints of prehistoric artists. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 13, 196 (2021).

Tomasini, E., Basile, M., Ratto, N. & Maier, M. Evidencias químicas de deterioro ambiental en manifestaciones rupestres: un caso de estudio del oeste tinogasteño (Catamarca, Argentina). Bol. Mus. Chil. Arte Precolomb. 17, 27–38 (2012).

Prieto, B. et al. A Fourier transform Raman spectroscopic study of gypsum neoformation by lichens growing on granitic rocks. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A, Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 55, 211–217 (1999).

Ilmi, M. M. et al. Physicochemical analysis of deterioration affecting the darkening of rock art in Maros-Pangkep, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 57, 104629 (2024).

Sepúlveda, M. Making visible the invisible. A microarchaeology approach and an Archaeology of Color perspective for rock art paintings from the southern cone of South America. Quat. Int. 572, 5–23 (2021).

Iriarte, M. et al. Micro-Raman spectroscopy of rock paintings from the Galb Budarga and Tuama Budarga rock shelters, Western Sahara. Microchim. J. 137, 250–257 (2018).

Rousaki, A. et al. Micro-Raman spectroscopy for the analysis of materials found in rock art shelters in Piedra Parada valley, Chubut province, Argentinian Patagonia. J. Raman Spectrosc. 53, 570–581 (2022).

Vadrucci, M. et al. Analysis of Roman Imperial coins by combined PIXE, HE-PIXE and μ-XRF. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 143, 35–40 (2019).

Oriolo, S. et al. Basalt weathering as the key to understand the past human use of hematite-based pigments in southernmost Patagonia. J. South Am. Earth Sci. 96, 102376 (2019).

Prieto-taboada, N. et al. Raman spectra of the different phases in the CaSO4-H2O system. Anal. Chem. 86, 10131–10137 (2014).

Defaria, D. L. A., Silva, S. V. & Deoliveira, M. T. Raman microspectroscopy of some iron oxides and oxyhydroxides. J. Raman Spectrosc. 28, 873–878 (1997).

Gunasekaran, S., Anbalagan, G. & Pandi, S. Raman and infrares spectra of carbonates of calcite structure. J. Raman Spectrosc. 37, 892–899 (2006).

Cardell-fernández, C. et al. The processes dominating Ca dissolution of limestone when exposed to ambient atmospheric conditions as determined by comparing dissolution models. Environ. Geol. 43, 160–171 (2002).

Tang, Y. B. et al. Dehydration pathways of gypsum and the rehydration mechanism of soluble anhydrite γ-CaSO4. Acs Omega 4, 7636–7642 (2019).

Charola, A. E. Salts in the deterioration of porous materials: An overview. J. Am. Inst. Conserv. 39, 327–343 (2000).

Gulzar, S. & Burg, J. P. Preliminary investigation of late Mughal period wall paintings from historic monuments of Begumpura, Lahore. Front. Archit. Res. 7, 465–472 (2018).

La Russa, M. F. et al. The Oceanus statue of the Fontana di Trevi (Rome): The analysis of black crust as a tool to investigate the urban air pollution and its impact on the stone degradation. Sci. Total Environ. 593, 297–309 (2017).

Krejsová, J. et al. New insight into the phase changes of gypsum. Mater. Struct. 57, 128 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Guangxi Institute of Cultural Relics Protection and Archeology for their invaluable support in conducting field surveys and experimental analyses.This work was supported by Guangxi Key Technologies R & D Program (No. AB22080102) and Scientific and Technological Research Project on Cultural Relics of the State Administration of Cultural Heritage (No. 2023ZCK019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W. and Z.R.Z. performed the examination, analyzed and interpreted the data, and were major contributors in writing the manuscript. B.C. assisted in performing the experiments. J.H.W. supervised the entire research procedures. H.B.Z. and Q.P.Y. came up with the initial project idea, contributed ideas to data collection and analysis, edited substantial portions of the manuscript, and is the corresponding author on this work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Zhu, Z., Cui, B. et al. Microscopic characteristics and weathering mechanism of pigment layers in Huashan Rock Art, Guangxi, China. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 307 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01873-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01873-x

This article is cited by

-

Research on traditional craftsmanship of ‘Shengfanhong’

npj Heritage Science (2025)

-

Investigation on surface condition surveys and study on weathering mechanism of the stone wall at the Zhouqiao bridge ruins in Kaifeng

npj Heritage Science (2025)