Abstract

Historic districts in developing countries undergo regeneration to preserve heritage and revitalize economies. Renovated building exteriors, as highly visible spatial elements, enhance vitality and sustain historical identity. Given that few studies have quantitatively examined exteriors’ impacts on regional vitality distribution, this study, reflected on Space Syntax, proposes a framework to assess exterior-renovation strategies at both local street and global network scales, involving: 1) identifying visitor-preferred exteriors and quantifying them as entropy to measure streets’ local attractiveness; 2) weighting streets by entropy to compute graph centralities for evaluating local attractions’ global impacts; and 3) employing the local, global, and Space Syntax metrics for regression analysis to reveal key contributors of visitor vitality. Taking the Chaozong historic district as a case, results reveal that current exterior strategies may constrain vitality to limited spaces, obscure visitor-perceived historical identity, and underscore the need to assess local attractions’ global impacts in relevant studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Historic districts in developing countries are deteriorating due to urbanization, motorization, modernization, and globalization1,2,3. Without proper intervention, these cultural-historical assets may risk degradation, leading to intergenerational inequity in accessing their economic, social, and cultural benefits4. To counteract the trend of decay, many practices have sought to preserve and revitalize historic districts, aiming to promote local and regional socio-economic development. Although interventions and their socioeconomic impacts vary globally, two key challenges persist: 1) the potential changes in local historical identity (HI)5,6,7 and vitality5,7,8,9,10 due to physical changes, and 2) the long-term impact of identity shifts on vitality4,11.

Among physical and environmental transformations, the most visually prominent modifications often involve building exteriors7, particularly those of non-landmark buildings (NLBs)—indistinct structures within intervention zones that do not meet the criteria for individual conservation11 and are therefore subject to more flexible renovation regulations. In contrast, landmark buildings (LBs), which possess exceptional heritage value11, are generally preserved to ensure the retention of their historical authenticity. Despite the difference, all exteriors are crucial spatial elements in sustaining vitality7, as the environments they shape influence people’s experiences. Attractive spaces can encourage people to linger, while uninviting surroundings may discourage engagement12,13, especially in historic districts where street spaces are primarily defined by continuous walls of attached and semi-attached buildings7. The substantial relationship between the perceptual qualities of exteriors and vitality14,15 underscores the importance of examining the exterior-associated factors and their impacts on visitor vitality (VV).

The investigation is especially pronounced in the implementation of exterior-renovation strategies (ERS) when considering the conservation of HI, as there are two distinct standpoints on the role of historic place identity in fostering vibrancy and sustainability. The first view, grounded in demand theory, regards the “uniqueness” of heritage assets as irreplaceable cultural and historical resources that attract consumers (or visitors) in heritage markets4,16. Thus, the impairment and erasure of past features are believed to diminish, or even eliminate, a place’s unique appeal, ultimately reducing its vitality and leading to decreased welfare for both current and future generations4. On the other hand, some designers and critics take an optimistic view of the evolution of HI, recognizing it as an inevitable aspect of the upgrading process. They argue that place identity is shaped and interpreted by individuals17,18,19,20,21,22,23, suggesting that even alterations that contrast with the historical ambiance can still appeal aesthetically to certain groups6,17. From this viewpoint, innovative and creative spatial designs are embraced to prevent intervention zones from becoming homogenized or mere replicas of historical styles24. However, in an era characterized by capitalist placemaking7,25, this viewpoint may promote the flexible and individualistic renewal designs25, which are often driven by market forces26,27. Although such efforts may attract capital and quickly alter the appearance of historic regions in the short term, they may also result in substantial and irreversible degradation of HI in the renewed areas, leading to undermined sustainability of historic districts in leveraging unique heritage values to generate long-term socioeconomic benefits.

These differing perspectives give rise to distinct ERSs, which are typically categorized into four approaches. The first, “contextual preservation,” focuses on maintaining authenticity, primarily for LBs. The other three—“contextual uniformity,” “contextual continuity,” and “contextual juxtaposition”17—generally apply to NLBs based on their relationship with historical settings, playing a more critical role in influencing place identity. However, as Heath et al.17 argues, none of these strategies prescribes a singular best practice for historic districts17. Therefore, a comprehensive investigation is necessary to assess the impact of various ERSs and their resulting outcomes on VV in historic district spaces. More importantly, such an investigation may facilitate a critical reflection on the HI transformation to indicate its sustainability.

Despite extensive research on vitality in the built environment since The Death and Life of Great American Cities28 by Jane Jacobs8, studies remain limited in examining the relationship between ERSs for building exteriors and VV in historic districts. First, quantitative research on exterior design strategies and historical place identity is lacking. Existing studies primarily approach historical placemaking qualitatively (e.g., 6,7,17,29,30,31). While these works offer valuable insights into heritage values embedded in building exteriors and their enhancement, they struggle to interpret how facades influence spatial vitality. Second, although some quantitative studies link observed vitality (e.g., pedestrian counts, POI, check-ins) to environmental factors (e.g., land use, greenness, openness, functional diversity)8,32, few examine how the perceptual qualities of exteriors shape visitor behavior or contribute to the environmental identity of historic areas. Third, most existing studies, particularly quantitative ones, implicitly assume that spatial factors influence vitality only within local spaces, without further examining their impact beyond the immediate areas. Although some studies integrate Space Syntax (SS)—a toolkit mainly rooted in spatial extrinsic property33—as regions’ global configurational factors with the local spatial factors of streets to enable comprehensive vitality investigation, the global influence of these locally treated street factors remains overlooked.

To bridge existing gaps, this study develops a quantitative framework, reflected on SS, to assess how different ERSs influence VV in historic districts at both local and global scales. Additionally, the insights derived from this framework enable the assessment of current visitor-perceived place identity by analyzing inferred movement patterns. Through evaluating the extent to which authentic HI contributes to the perceived identity, the impact of current ERSs can be inferred—whether they enhance or erode the historic character—thereby shedding light on historic districts’ sustainability. To contextualize this study, the remainder of this section reviews literature regarding two key areas of prior research: 1) the principles and heritage implications of ERSs, alongside the ERSs’ potential influence on HI, and 2) recent quantitative approaches to evaluate VV in urban environments.

The first part outlines the current theoretical insights and conservation principles that inform ERSs (contextual preservation, uniformity, continuity, and juxtaposition), with a particular emphasis on the potential outcomes of resulting HI shifts.

Historical contextual preservation follows the principle of “minimum intervention” as proposed by ICOMOS34, which advocates for minimizing alterations to ensure safety and durability while causing the least harm to heritage values34. The goal of this strategy is to preserve the authenticity of heritage assets, a principle first introduced in the Venice Charter35 and later reinforced in the Nara Document on Authenticity36 and UNESCO’s Operational Guidelines37. Referring to the exterior renovation, the preservation of authenticity is of profound significance to a place’s HI.

As the most visually prominent elements of a historic space, facades and frontages with genuine HI are key determinants in shaping people’s perceptions of historical authenticity5,38. The experiences are largely informed by exteriors’ roles as tangible records of spatial and social transformations, conveyed through their architectural forms, compositions, and historical contexts7,39,40, while also manifesting technological advancements41, public engagement, and evolving social preferences7. Such historic evidence can evoke visitors’ past-related emotional responses42 and cultural-historical memories7, which are key to the enhancements of both the attractiveness of HI and the vibrancy of historic places. Preserving the authentic heritage interpretation of historic sites is thus crucial not only for boosting and sustaining the vitality of the historic built environment but also for benefiting present and future generations economically and socio-culturally. This value is recognized by both local and external stakeholders, as consistently emphasized in academic research (e.g., 4,5,8,43,44,45,46) and established management guidelines (e.g., 6,29,47,48).

Apart from conservative contextual preservation, many practitioners have defined additional ERSs based on their own understandings of place identity. The design guideline proposed by the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia (PAGP) classifies ERSs into four categories: “literal replication,” “invention within the same or a related architectural style,” “abstract reference,” and “intentional opposition”48,49. Similarly, Heath et al. categorize architectural interventions into three approaches: 1) “contextual uniformity,” 2) “contextual continuity,” and 3) “contextual juxtaposition”17. These definitions of ERSs overlap: both “literal replication” and “invention within the same or a related architectural style” aim to enhance homogeneity, aligning with Heath et al.’s concept of “contextual uniformity.” Similarly, “contextual juxtaposition” involves striking contrasts to create dramatic aesthetics, echoing the “intentional opposition”. The key distinction lies in Heath et al.’s “contextual continuity,” which emphasizes “time succession”17,38, whereas PAGP’s “abstract reference” in modernist approaches focuses on compatibility between new and historic structures through simplified, abstract forms48,49. Despite this, the underlying goal of both “abstract reference” and “contextual continuity” is to mediate the polarity between antiquity and modernity17,38,48,49, meaning that “abstract reference” can be incorporated within “contextual continuity.”

However, these strategies do not dictate one ideal renewal solution for historic areas17, rather, more likely, leading to transformations of the original identity, including: 1) Contextual uniformity - while this approach seeks to preserve and reinforce original historic features, Mumford50, Lynch38, and Heath et al.17 caution that it may risk freezing historic identity at a specific point in time, creating a monotonous environment. Furthermore, studies51,52,53,54,55,56 suggest that such replicas may obscure the distinction between originally and artificially created elements, diminishing the ability to recognize and appreciate authentic history, ultimately leading to a place devoid of meaningful connection24; 2) Contextual continuity - this approach fosters a sense of continuity between different time periods, linking the past with the present. However, it has been criticized for its “superficiality”17, with Hewison57 arguing that these designs often appear as modern fabrications, resembling theatrical performances rather than serious historical analysis. This can lead to gentrification, particularly in East Asian cities, where historic districts are transformed into fashionable urban hubs featuring upscale restaurants and boutiques58. Additionally, neglecting a place’s history can undermine its significance59 and authenticity58, hindering the development of a deeper, evolving understanding of historic places6; 3) Contextual juxtaposition - this strategy emphasizes the striking contrast between past and present, fostering aesthetic diversity17 and creativity60,61,62. However, as Heath et al. point out, two negative consequences can arise: First, a lack of attention to the broader context may diminish the historical significance of the site; Second, excessive use of juxtaposition may result in visual chaos and loss of dependent historical contexts. More crucially, decontextualized facade designs show little regard for environments rich in cultural, historical, and social significance63, risking a loss of their sociocultural and symbolic value64.

The second part of the review addresses the current approaches applied to assess visitor vitality (VV) in urban contexts. Existing research on historic building renovations and their impacts on perception or sense of place remains largely qualitative (e.g., 6,7,17,28,48,65,66). While these studies provide important insights into the heritage values conveyed through building exteriors and the potential implications of renovation practices, they often lack clarity on how specific exterior characteristics influence measurable spatial vitality. This gap highlights the need for incorporating quantitative methods into the analysis of this domain.

However, as illustrated in Table 1, quantitative research specifically addressing the impact of exteriors on vitality remains scarce. Current quantitative studies on urban vitality tend to focus on identifying appropriate vitality proxies and relevant influencing factors, e.g., physical and demographic features, before employing statistical methods to evaluate their effects. Typically, these studies utilize street segments as the fundamental spatial unit to enhance the generalizability of vitality proxies and their influencing factors, reducing variations associated with finer spatial scales and improving the explanatory power of statistical models.

Li et al.32 and Mu et al.67 carefully select locations for video recordings to ensure high-quality data for analysis, capturing pedestrian volume and behavior patterns. By analyzing the footage, Mu et al.67 document pedestrians’ walking and stopping patterns, linking them to environmental factors such as street width, openness, greenery, and storefront transparency. Similarly, Li et al.32 utilize multiple-object tracking (MOT) to count pedestrian volumes in videos and examine the relationship between pedestrian counts (the dependent variable) and various environmental factors (similar to those identified by Mu et al.67). Instead of cameras, Li et al. used “Citygrid” sensors to collect hourly pedestrian flow data at different locations. Additionally, they gather a variety of environmental data (e.g., temperature, humidity, PM2.5, luminance), visual data (e.g., greenery and sky visibility), and spatial configurational data (e.g., integration and choice), which are analyzed using generalized estimating equation (GEE) to assess the contribution of spatial variables to pedestrian volume. Other studies have similarly employed statistical models to examine the correlation between environmental factors and vitality, utilizing proxies such as GPS data (e.g., 68,69), phone calls (e.g., 70), geolocation check-ins (e.g., 71,72), and surveys (e.g., 73,74), as seen in Table 1. Even though some studies (e.g., 75,76,77) do not strictly adhere to this trend, they still associate vitality or its related concept, “walkability,” with specific properties of street spaces.

Given that districts are typically composed of interconnected street spaces, researchers have recognized that vitality is closely linked to regional spatial configuration. SS is the most commonly used analytical toolkit for assessing accessibility within broader street networks. As highlighted in Sharmin and Kamruzzaman’s meta-analysis, SS has proven to be a powerful tool for studying pedestrian wayfinding in urban environments78. The foundation of applying SS in studying pedestrian behavior stems from the “natural movement” theory, which suggests that the flow of urban pedestrian movement is largely determined by the spatial configuration of street spaces, according to the founder of SS, Bill Hillier79. However, Hillier acknowledges that in some cases, the influence of attractors, such as shops or public spaces, can outweigh the impact of spatial configuration79. He refers to this as movement driven by attractions, known as the “attraction theory”79,80,81, and stresses that design functions to regulate the localized effects of these attractions79.

Although not all researchers explicitly refer to the theories of “natural movement” and “attraction,” some studies (e.g., 8,69,73,74,82) have recognized both local and global factors as key influences on pedestrian behavior and vitality. These studies typically employ SS metrics (e.g., integration and choice) as global configurational factors to capture the “natural” proportion of pedestrian movement, while also integrating various local environmental factors (e.g., street width, openness, greenery, transparency) to account for the influence of “attraction.” The hybrid approach is considered more comprehensive, effectively addressing criticisms of SS’s over-abstraction of various spatial factors33, particularly the exclusion of environmental attractors linked to visitors’ preferences, which are crucial for wayfinding behavior83,84,85,86.

Despite the valuable contributions made by existing quantitative vitality studies, several issues emerge regarding the exploration of the impacts of exterior renovations on vitality, including: 1) The limited representativeness of current proxies used to assess vitality specifically driven by building exteriors. Although current data capture pedestrian spatial preferences within specific regions, these preferences are influenced by various multidimensional factors, indicating that they are not solely driven by building exteriors. Consequently, a more representative vitality proxy should be discovered, specifically linked to pedestrians’ or visitors’ perceptual experience of building exteriors; 2) The insufficient focus on environmental factors directly related to building exteriors. Spatial elements related to building exteriors are often minimal (e.g., transparency of facades or storefronts67,68) or even overlooked in many studies, not to mention investigating the ERSs’s impacts on vitality. Hence, the environmental factors ought to be centered on the ERSs in alignment with the aim of this study. 3)The overlooking of the broader, global influence that local environmental factors may exert on pedestrian behavior. Existing research has not explicitly examined the potential global influence of locally situated factors, assuming these only affect pedestrian behavior within immediate spaces without extending to other areas. Even Hillier, in his discussion of attraction theory79,80, does not address this issue directly. However, based on the SS classification in the textbook by Nes and Yamu81, which categorizes SS as a tool for evaluating the invisible “extrinsic” properties of space, local environmental factors are conventionally considered to influence only the local scale. Nonetheless, this categorization may be problematic, as local factors can influence pedestrian behavior at a global level. This is evidenced by two key observations: Firstly, at junctions, where visitors must make route choices, they are more likely to enter streets with appealing spatial elements, avoiding those without such attractions, and secondly, visitors’ arrival at specific streets often results from accumulated route choices, particularly those streets located within the region but not directly accessible from the boundaries. Therefore, local environmental factors not only influence visitors’ spatial experiences but also play a significant role in their route choice behavior. The former impact is intrinsic, while the latter, arising from comparisons to other spaces, reflects the extrinsic aspect of local factors. This dual influence emphasizes the importance of measuring both studies of visitor behavior and vitality. 4) The lack of rigor and transparency in the interpretation of statistical models analyzing vitality. Studies using statistical modeling to analyze vitality often lack rigorous protocols for validating their results. One major issue can be attributed to the negligence in properly checking data assumptions, which is crucial for validating the choices of statistical models. For instance, linear regression models require verification of assumptions, such as the normality of residuals and the independence of observations87, while Poisson GLM need to account for the assumption of equidispersion in count data88. Multicollinearity, which occurs when predictors are highly correlated, can inflate standard errors and lead to unreliable coefficient estimates, thus undermining the interpretability of findings—a limitation overlooked by some of the aforementioned studies (e.g., 8,32,67,73,74,82,89). Another problem arises when studies refuse to eliminate statistically insignificant variables in order to prioritize model comprehensiveness (e.g., 73,90). While this approach may help maintain the thoroughness and fitting goodnes, it increases the risk of overfitting, complicates the identification of key relationships, inflates standard errors, and reduces the overall precision of the model’s estimates.

Methods

Vitality proxy

As discussed earlier, a more appropriate data typology is required to better capture the relationship between vitality and renovated exteriors. Table 2 outlines the strengths and limitations of potential proxies and their corresponding data sources, such as pedestrian counts and geolocation footprints. Among all data typologies, the user-posted images on RedNote offer most valuable insights into how building exteriors function as attractions and contribute to visitors’ place attachment. Therefore, these images are especially pertinent to this study because of their large volume, explicit focus on renovated exteriors, and precise geolocation reference.

Nevertheless, the demographic composition of RedNote users may introduce biases in representing on-site visitor vitality, primarily due to two reasons: Firstly, the overrepresentation of female users (79.13%91) compared to the actual gender distribution of the surveyed on-site visitors, as demonstrated in Table 4; Secondly, the challenge in determining whether the dominant age groups of real-world visitors (as indicated by RedNote) can adequately represent the preferences of minority ones lies in assessing their levels of agreement regarding facade renovation styles and visual quality—two key dimensions used to categorize exteriors and form the basis for subsequent assessments of street attractiveness. The impacts of the biases using user-posted images in RedNote as vitality proxy are further investigated in 2.2 Vitality Factors. In summary, the predominance of female users on RedNote may have limited impact on the validity of representing male visitors’ spatial preferences, as indicated by the “substantial agreement” measured by Cohen’s kappa between the major age groups across genders, which together account for over 65% of the surveyed visitors. However, determining whether dominant age groups (indicated by RedNote report92) can similarly represent minority age groups proves more challenging. This difficulty primarily stems from the much smaller sample sizes of the minority age groups, which increases the likelihood of modal value fluctuations. As a result, the modes of these smaller groups may not accurately reflect the actual preferences of their members and undermine the reliability of their agreement levels with the majority age groups. Nevertheless, since the minority age groups constitute less than 34% of the total visitor population, their influence on the overall representativeness of RedNote as a vitality proxy remains limited. Therefore, despite potential biases, particularly the underrepresentation of visitors younger than 18 and older than 35, the RedNote user-posted images can still be regarded as a valid proxy for capturing the perceptual tendencies of the majority of visitor groups with respect to exterior evaluations and spatial vitality.

After determining the biases of using RedNote images as a vitality proxy, the user-posted images are collected through RedNote’s server via an authorized API. A total of 15,341 images were retrieved after searching for “Chaozong.” The images were processed according to following prodedures (see Fig. 1):

-

Removing unrelated images: Excluding photos from outside Chaozong or those not featuring building exteriors (e.g., interior spaces, food).

-

Removing unidentifiable and duplicated images: Some images could not be identified due to insufficient information, and some were posted multiple times.

Then, the sites in the remaining valid images are distinguished, counted, and georeferenced to the map. The illustration is created by the authors based on self-taken photographs (some of which were digitally enhanced using generative AI (DALL ⋅ E model) to include virtual human figures), representing conditions observed in publicly shared user-posted images, without directly displaying the original user content, in order to avoid potential copyright infringement.

1426 images remained after removing invalid images. After identifying the locations from these images, including multiple locations indicated by stitched photos, 2355 instances of exterior check-ins were generated and assigned to the corresponding buildings for further analysis (Fig. 1).

Vitality factors

As previously noted, existing studies have not explicitly examined the global influence of local attractions within a region. Therefore, this study aims to address this gap by quantifying the attractiveness of attractions not only at the immediate street level but also within the broader global street network of a historic district. By incorporating SS metrics with these two typologies of quantified attractiveness, a more comprehensive environmental-factor conceptualization can be developed to complement Hillier et al.’s natural movement and attraction theories by providing a perspective that synthesizes them. The factors defined for this study includes:

-

Configurational factors: “SS metrics (SSM)” as informed by the “natural movement theory.”

-

Local attraction factors: “Intrinsic attractiveness metrics (IAM)” quantifying the appeal of attractions within each street, suggested by the “attraction theory.”

-

Global attraction factors: “Extrinsic attractiveness metrics (EAM)” measuring the global influence of the attractiveness of each street’s local attractions, inspired by the synthesis of both the natural movement and attraction theories.

Since the attractions in this study are the building exteriors renovated or preserved (hereafter referred to as “renovated exteriors” for convenience) according to different strategies, the quantification of attractiveness (IAM and EAM) is specifically tailored to the exteriors in street spaces.

Other environmental factors explored in previous studies are not further examined here. The rationale for focusing on exterior-related vitality factors is threefold: Firstly, the renovated facades of low-rise buildings are the primary visual and experiential attractions in the Chaozong Historic District, while other factors, such as greenery and spatial openness, are relatively uniform and less impactful on vitality; In addition, the selected vitality proxy captures the portion of vitality linked to building exteriors, reducing the need to consider other factors; Thirdly, focusing on exterior-related elements aligns with the core research aim to assess the impact of ERSs on VV, ensuring methodological coherence and directly addressing how building exteriors contribute to the district’s revitalization.

The first step is to define SSM. Hillier80 argues that a region’s center, marked by concentrated and diverse activities, is rooted in spatial-functional centrality, which depends on the topological relationships between spaces, suggesting that understanding topological centrality is essential to unveil the historical development of spatial hubs and informing future decisions.

In SS, the key metrics for analyzing urban space configurational properties are integration (closeness centrality) and choice (betweenness centrality)93, which promotes the understandings of pedestrian behavioral dynamics78. Integration reflects a certain topological space’s potential to be a popular destination, while choice gauges a space’s role in facilitating through-movement along the shortest paths between origins and destinations94. Spaces with high integration values often observe significantly larger quantities of pedestrian arrivals, while those with high choice tend to become more constant “stepstones" as trip lengths increase94. In other words, integration identifies the spatial center, while choice reflects the structural framework of the network which exhibits less variation.

Though originally based on sole topological connections, integration and choice have been expanded to consider human perception in navigation. For example, Turner95 introduced the angular-weighted shortest path, and the resulting angular-weighted integration and choice, suggesting people prefer routes with minimal angular changes, even if the distance is longer93,95. Rashid96 refined the graph by incorporating the metric length of road segments as an additional weighting factor, establishing the metric-length weighted centralities. However, this study does not employ existing weighted metrics for two primary reasons. First, the use of angular changes to determine segmentation points along sinuous road centerlines can introduce ambiguity and result in an excessive number of overly fine-grained segments with no recorded check-ins. Such fragmentation is likely to reduce the explanatory power of subsequent statistical models. Moreover, as noted by Turner97, the founder of Angular Segment Analysis, caution is warranted when applying such methods due to the potential cognitive limitations of pedestrian navigation. Specifically, the principle of “minimal angular change” aligns more closely with “utilitarian wayfinding,” wherein individuals prioritize travel efficiency, and may not adequately capture the exploratory behaviors typically exhibited by visitors in tourist-oriented environments, such as Chaozong. Furthermore, as road segments do not exceed 200 meters, the distances are rather short for walking, rendering length-based weighting unnecessary. Thus, only the non-weighted integration and choice are chosen as SSMs, which act as pure configurational factors in this study.

Another key challenge arises in determining appropriate methods for defining the topological spaces that underpin the calculation of spatial structure metrics (SSMs). The well-established axial-line method, which abstracts the longest-sighted space as a node, has been criticized for being “subjective and arbitrary”98. In contrast, the “line-segment map” method99, which divides road centerlines at junctions, offers a more objective alternative. However, this method may still result in numerous short segments with minimal check-ins or renovated exteriors, similar to the angular segmentation issues discussed earlier.

To address these limitations, the present study primarily adopts the “road centerline” mapping approach99, which avoids fragmentation caused by sinuous or multi-turn street segments. Segments that lack check-in data and/or identifiable exteriors (i.e., attractors) due to junction-based division are further merged with adjacent segments based on two rules. The first one is the angular continuity - connecting short segments (less than 50 m) to neighboring segments with minimal angular deviation. The second rule is concerning image similarity - linking segments to their immediate neighbors with maximal similarity in perceptual characteristics of the built environment, including, though not limited to, openness, building arrangement, and facade materials (Fig. 2). The final processed segment map, along with its topological structure, is presented in Fig. 3.

First, defining segments by dividing road centerlines at junctions. Second, merging short segments or those with zero check-ins into adjacent segments with the least angular deviation or the highest image similarity (e.g., openness, building arrangement, facade materials) to enhance statistical analysis. The merged segments are marked by elliptical masks in different colors, each representing a corresponding reason, as indicated in the legend.

The next vitality factor to be defined is IAM. Since renovated exteriors are the primary attractions in this study, IAM assesses street attractiveness based on the richness of exterior choices for check-ins, considering visitor preferences for ERSs.

In psychology, entropy quantifies uncertainty from the diversity of options in decision-making tasks, and its efficacy has been confirmed100,101,102,103,104. Similarly, in this study, the richness of exterior choices is measured using entropy derived from information theory, which represents the average level of unpredictability associated with the potential outcomes of a variable105, where the “variable” refers to the choice of exterior made by visitors for check-in (taking a photo), and the “potential outcomes” correspond to the different exteriors that visitors may choose. To clarify, a higher entropy value indicates that a street offers a greater variety of attractive exterior options but simultaneously reduces the likelihood—or certainty—of any single exterior being chosen by visitors for check-in, even if these facades have been renovated with the same ERS (same ERS but different appearances). Conversely, lower entropy implies that a few exteriors dominate visitor check-in behavior, leading to fewer choices and greater predictability in selection. In short, the entropy value is positively associated with the attractiveness of the immediate space.

To calculate entropy, the primary challenge is to determine the probability distribution of exterior choices for check-in. Although many factors influence the selection probabilities, this study assumes equal probability for each exterior deemed “attractive”. This premise is justified by two reasons: the first one is regarding data limitations, where many exteriors lack check-ins due to insufficient data or a short observation period, while the other is the aim to maximize theoretical richness, ensuring consistent comparability across street spaces. Thus, the probability of selecting an exterior is simply determined by the total number of visitor-preferred exteriors. However, since exact visitor preferences cannot be predetermined, this study considers all possible combinations of ERS categories in order to account for the full range of potential exterior-preference scenarios. In the later statistical analysis, the specific ERS types that are significantly preferred (or disfavored) by current visitors can be revealed by the weights of associated explantory variables in regression results. The construction of ERS combinations begins with the fundamental step of defining the distinct ERS types.

Table 3 illustrates the three ERS types (contextual uniformity, continuity, and juxtaposition) for NLBs, alongside the preservation of authentic LBs. The corresponding ERS styles are classified as “True-historic (TH),” “Fake-historic (FH),” “Adapted or Abstracted-historic (AH),” and “Non-historic (NH)” in Chaozong’s building exteriors. Since the visual quality of renovation designs significantly influences visitor attraction by enhancing aesthetic appeal, spatial identity, and emotional attachment, primarily determined by design forms, materials48,67,106 and execution precision6,48—this dimension is crucial in evaluating renovation works. Thus, each ERS is categorized into three visual quality levels: “High (HQ),” “Medium (MQ),” and “Low (LQ),” as detailed in Table 3.

The next step in this study is to categorize the renovated exteriors in the Chaozong Historic District. Owing to the large amount of exteriors (nearly 300), surveying all visitors is impractical. Instead, a sample group of exteriors is used to assess the consistency in exterior-categorization tasks between actual visitor and an expert team of 8 scholars from architecture and urban design domains. Once a satisfactory level of consistency is achieved, the expert team will finalize the categorization for all exteriors.

The in-situ survey involves the following steps:

-

Survey introduction: Visitors were informed about the research, including its purpose, the meanings of ERS categories, and instructions for completing the survey.

-

Survey procedure: Each participant was presented with 60 images of building facades on an iPad (Some samples illustrated in Fig. 4). The images were systematically sampled to ensure balanced representation, with five examples for each combination of renovation style and visual quality, based on expert-defined categories to minimize potential classification bias. During face-to-face interaction, the researcher manually recorded visitors’ selections, along with their sex and age range. To promote attentive and reflective responses, the survey was administered in person rather than through self-completion. This approach aimed to reduce the likelihood of hasty or superficial choices, in order to enhance the validity of the collected data.

Fig. 4: Example facades and storefronts renovated (or preserved) under different strategies with color dots and codes representing their categories. a–c True-historic exteriors with high, medium and low visual qualities; (d–f) Fake-historic exteriors with high, medium and low visual qualities; (g–i) Adapted or abstract-historic exteriors with high, medium and low visual qualities; (j–l) Non-historic exteriors with high, medium and low visual qualities. The explanations of the ERS and code are demonstrated in Table 3.

-

Data analysis: To assess visitor perception of building exteriors, visitor responses were first aggregated to identify the modal classification—the most frequently selected category—for each facade in terms of renovation style and visual quality. Modal values were calculated for the overall participant pool as well as for specific demographic subgroups defined by sex, age range, and their intersections. These group-specific modal categorizations were then compared to expert-defined classifications to evaluate the level of agreement between expert and lay evaluations. To quantify this agreement, Cohen’s kappa coefficient—a widely used statistical measure for assessing inter-rater reliability with categorical data107—was employed. In this context, it provided a measure of consistency between expert judgments and visitor responses, in order to assess the reliability of expert classifications across nearly 300 building exteriors in the Chaozong district.

The application of Cohen’s kappa in this study assumes that conditions as proposed by Cohen108 are met. First, the categorical labels used to classify renovation style and visual quality are mutually exclusive, collectively exhaustive, and independent, ensuring that each building exterior is assigned to one and only one category within each dimension. Second, the raters - in this case, the experts and visitors — make their judgments independently, without mutual influence. These assumptions support the validity of Cohen’s kappa as a metric for evaluating agreement in this context. Beyond assessing agreement, this comparative framework also aimed to reveal potential demographic biases. Such biases may not only influence the validity of expert-defined categories but also affect the representativeness of RedNote user-posted images, the vitality proxy.

As shown in Table 4, the on-site survey engaged 466 participants who have shown “substantial agreement” with experts on both renovation style (0.689) and visual quality (0.750), indicated by the established interpretation of Cohen’s kappa (value between 0.60 and 0.80 suggesting “substantial agreement”109). Figure 5a reveals lower participant agreement with expert classifications, particularly in distinguishing FH and AH exteriors. Specifically, seven facades identified by experts as TH or AH are frequently perceived as FH by visitors, while four expert-classified AH facades are interpreted as NH. Besides, visitors demonstrate greater generosity in their assessments of visual quality compared to experts, as they tend to assign higher ratings to exteriors that experts have classified as medium or low in visual quality (Fig. 5b). Despite the disparities, overall, the expert team’s evaluations of the renovated exteriors are broadly aligned with the perceptions of the majority of visitors.

The confusion matrices represent the agreement conditions of 60 sample exteriors’ ERS styles (colored in blues) or qualities (colored in purples) between different demographic groups: a, b experts and all survey participants; c, d experts and female aged 18–24; e, f experts and female aged 25–34; g, h experts and male aged 18–24; i, j experts and male aged 25–34; k, l male and female aged 18–24; m, n male and female aged 25–34; o female aged 18–24 and 35–44; p male aged 25–34 and 35–44; q female aged 18–24 and over 44; r male aged 25–34 and 18–24.

However, the kappa values at the general level may be biased, as the quantities of demographic groups are imbalanced. Since the categorization of each exterior’s style and visual quality is based on the modal response across all participants, demographic groups advantaged in quantity are more likely to exert a disproportionate effect on the Cohen’s kappa values. As illustrated in Table 4, female visitors accounted for approximately 60% of the total survey participants, with 25.32% aged 18–24 and 17.60% aged 25–34. In contrast, although the two male age subgroups — those aged 18–24 (9.87%) and 25–34 (12.66%) — outnumber other male age groups, their proportions remain significantly lower than those of their female counterparts in the same age ranges. Consequently, the Cohen’s kappa values for female subgroups tend to align more closely with the overall agreement levels than those of the male subgroups. This pattern is exemplified by the style agreement comparisons between female and male participants aged 18–24 (Fig. 5c, g) and 25–34 (Fig. 5e, i). A similar trend is also observed in the agreement on visual quality, as indicated by the comparisons in Fig. 5d, h, as well as Fig. 5f, j. Specifically, male participants aged 18–24 demonstrated a markedly higher level of agreement with expert classifications in terms of renovation style (0.778), but a substantially lower level of agreement in visual quality assessments (0.600), when compared to their female counterparts (0.622 and 0.675). Nevertheless, given their relatively small proportion within the overall sample (9.87%), the influence of this subgroup on the aggregate kappa values remained limited.

Another bias of the general kappas lies in the potential imprecision in reflecting the agreement levels between experts and the minority demographic groups—namely, female and male participants in the less represented age ranges (e.g., under 18, 35–44, over 44, and non-reported). Due to their small sample sizes, these subgroups are more susceptible to statistical variation, which may lead to reduced levels of agreement with expert classifications, as observed in Table 4.

Although such biases may limit the representativeness of the overall kappa values for every demographic subgroup, the use of general kappa statistics in this study still offers a sound measurement. Given that the regeneration of Chaozong is strategically aimed at attracting younger groups (18–34), particularly female visitors—a trend corroborated by the survey data (Table 4)—the evaluations of renovated exteriors by these groups are likely to exert a disproportionately greater influence on the perceived vitality distribution across Chaozong, compared to those of less represented subgroups. Therefore, while the sample’s demographic imbalance raises biases among underrepresented subgroups, it simultaneously enhances the representational accuracy of the majority perspective and thus yields a more realistic depiction of how most actual visitors engage with the built environment. As a result, the survey data provide empirical support for the validity of the experts’ categorizations, suggesting they reasonably approximate the broader preferences of visitors. Figure 6 presents the final expert categorizations of building exteriors across Chaozong, along with their spatial distribution and corresponding street segments.

In addition to the kappa values, discrepancies in the demographic compositions of surveyed visitors and RedNote users may introduce biases when using user-posted images as a proxy for visitor vitality. According to RedNote-user demographic reports, nearly 80% of users are female91, with the majority concentrated in two age groups: 18–24 (39.21%) and 25–34 (38.65%)92. While the in-situ survey result (Table 4) reveals a comparable age distribution—35.87% for the 18–24 group and 30.47% for the 25–34 group, it shows a markedly higher proportion of male visitors (38.0%), nearly twice that of the reported 20% for RedNote users. This discrepancy suggests that using RedNote user-posted images as a vitality proxy may lack representativeness for male visitors in real-world contexts. To further investigate the extent of this gender-related bias, the agreement levels between genders within the two dominant age groups (18–24 and 25–34) are evaluated concerning renovation style and visual quality. As demonstrated in the confusion matrices (Fig. 5k–n), both female and male visitors generally exhibit substantial agreement regarding the style and quality of the sample exteriors, despite 0.596 (Fig. 5k), a value rather approaching to the “substantial” threshold, for the two gender groups aged 18–24 on style. This level of consistency suggests that the principal male demographic groups may share similar perceptions with their female counterparts, potentially resulting in comparable behaviors in terms of check-ins and route choices. Consequently, the inference helps mitigate the influence of gender-related biases within the 18–34 age group, who account for the majority of both RedNote users (79.13%) and real-world visitors (65.45%), thereby enhancing the overall demographic alignment of the vitality proxy.

When examining potential biases across age groups, assessing the agreement between major and minor age groups proves more challenging due to the greater variability associated with the much smaller sample sizes (≤30) of age minorities. For example, the Cohen’s kappa measuring style agreement between female visitors aged 18–24 (25.32%) and those aged 35–44 (3.22%) indicates only “fair agreement” (Fig. 5o), despite each group individually exhibiting “substantial agreement” with expert categorizations (Table 4). This reduced consistency may either stem from an inherent age-related bias or from increased variability in the modal responses within the 35–44 group, which contains only 15 samples. A similar pattern is evident in the evaluation of style and quality agreements across other age group comparisons, including between males aged 25–34 and 35–44 on style (Fig. 5p), females aged 18–24 and those over 44 on quality (Fig. 5q), and males aged 25–34 and 18–24 on quality (Fig. 5r). While the potential biases associated with age-minority groups remain ambiguous, thereby constraining the full representativeness of RedNote images as a vitality proxy, these groups merely constitute less than 35% of the total visitors - this suggests that RedNote data can still serve as a broadly valid proxy for estimating spatial vitality among the majority demographic.

Following the classification of ERS types, the next analytical step concerns defining potential ERS preference classes (or ERS combinations) for visitors. These classes include a wide range of exterior combinations regarding styles and qualities, yet the ones representing medium or low visual quality are not designated as independent or joint preference classes, based on the following considerations:

-

High-quality exteriors are widely acknowledged as effective visual attractors, capable of arousing visitors’ interest in specific street segments and encouraging behaviors such as lingering or photo-taking. In contrast, low-quality exteriors are typically less likely to function as standalone attractors, often being disregarded by passersby or even deterring their further exploration. Nevertheless, their contribution is not entirely negligible. In certain scenarios, low-quality exteriors may enhance the perceived stylistic coherence of a segment or contribute to streetscape vibrancy by increasing the number of visible facades (e.g., ZSXL-3-4 in Fig. 6). Medium-quality exteriors, situated between these two extremes, tend to exert a more moderate yet contextually relevant influence. Their role as attractors becomes particularly apparent when they co-occur with high-quality exteriors, where they may reinforce stylistic impressions or increase the diversity of visually engaging elements within a segment.

-

Regarding the co-occurrence of exteriors with different quality levels, a guiding principle for classifying visitor preference classes is established: when lower-quality exteriors co-occur with superior-quality ones, they function as attractors only in conjunction with the latter. In other words, inferior-quality exteriors cannot serve as independent attractors when better-quality exteriors are present. Consequently, it is not meaningful to define a “low-quality” preference class when high- or medium-quality exteriors are also present within the same segment. Even if in segments composed exclusively of low-quality (e.g., ZSXL-3-4), medium-quality (e.g., GY-3), or both (e.g., FQ-2), “Total” or “Above-low” classes (Fig. 7) have already incorporated three scenarios. Particularly, the “Above-low” is defined to account for the condition that medium-quality exteriors are deemed the only effective type of attractor in segments where the lower-quality ones coexist (e.g., FQ-2).

Therefore, establishing distinct preference categories for medium- and low-quality exteriors, either individually or in combination, can be redundant and hence deemed unnecessary.

Stemming from the standpoint that place identity is shaped and interpreted by individuals, this approach takes all possible visitor-preference scenarios into account. Based on this, the attractiveness of a specific street for visitors with certain preferences can be evaluated accordingly, enabling the street-attractiveness based wayfinding simulation within the network.

After defining preference classes, IAM for specific spaces and preferences can be computed. Equation (1) represents the entropy value of renovated exteriors, where the total number of exteriors is n within preference-class C (Fig. 7) in road segment V. The probability of each renovated exterior occurring in this class, denoted as pi, is assumed to be equal to 1/n. The equal probability allows Eq. (1) to be further simplified as Eq. (2). One is added to keep the argument n from being zero, in case there may be no renovated exteriors of a particular class in some segments. Figure 8 demonstrates the process of IAM computation.

The richnesses of three kinds of visitor-preferred exteriors—“true-historic,” “above-low-quality,” and “non-historic high-quality”—are calculated for virtual segment V by first counting the number of exteriors within each preference class. Subsequently, the entropy value is computed based on the assumption that visitors check in with equal probability among all selected exteriors.

The final vitality factor, EAM, serves as the extrinsic counterpart to IAM, assessing the external influence of attractions within a segment in the context of the entire network. Like SSM algorithms (e.g., axial, angular, etc.) which presume natural movement following paths characterized by the shortest topological or weighted-topological distances between any two nodes, EAM ought to rely on an exterior-attractiveness based shortest-path assumption before conducting graph computation. In this study, the assumption is that visitors tend to choose “paths between any two nodes that provide the maximum-average entropy gain per topological step.” The rationale for this assumption includes:

-

The concept of “maximum entropy gain” suggests that visitors tend to favor segments with more pronounced aesthetical identities over spaces lacking such characteristics. This suggests that visitors naturally select routes aligning more closely with their preferred place identity.

-

The term “average” reflects visitors’ tendency to optimize their travel experience efficiently. Instead of taking unnecessary detours to pass through all visually appealing segments (attraction-led travel), visitors are more likely to select routes with relatively short topological distances that still maximize their experience. This balances attractiveness with configurational efficiency, especially when the destination is near the origin.

Based on this assumption, graphs with nodes weighted by IAMs in various visitor-preference scenarios can be constructed, enabling the computation of closeness and betweenness centralities within the weighted graphs. To ensure terminological consistency with SSM, these entropy-weighted graph metrics are referred to as Entropy-Weighted Segment Integration (ESIN) and Entropy-Weighted Segment Choice (ESCH).

The computation of ESIN is comprised of two steps:

-

1.

Finding the “shortest path with maximum-average entropy gain (SMHP)” for all source-target node pairs: Since the SMHP may not coincide with the shortest topological path defined in axial analysis, this study identifies the SMHP among the first k shortest simple paths Fig. 9, as proposed by Yen110. This approach expands the selection of shortest paths, allowing for the identification of the one that maximizes average entropy gain. By restricting the search to the first k shortest topological paths, the computational complexity of evaluating all possible paths, many of which involve excessive detouring, is significantly reduced. Equation (4) defines the maximum entropy gain per topological step, reflecting visitor-preference class C, from source S to target T, among all segment-combinations within the first k shortest topological paths (Eq. (3)), where V represents all nodes except S. The total entropy gain, represented by the summation of H(V, C), is then averaged by the number of steps, \(\frac{1}{| {P}_{i}| -1}\). It is important to note that SMH(S→T, C) excludes the entropy value of the source S, H(S, C). This exclusion in the algorithm rests on a presuppositions that the starting segment S of a journey is not part of wayfinding choices, and thus travelers cannot optimize their experience at the beginning. Contrarily, while the target space T is also predetermined, its inclusion in the algorithm is necessary as its IAM value may imply T’s potential for being chosen as a destination relative to all other target spaces (i.e., the higher the IAM of a T, the more likely it is to be a popular destination). Consequently, the path(s) exhibiting the maximum-average entropy gain (SMH) are denoted as SMHP(S→T, C) (Eq. (5)). This represents a set of paths because more than one shortest path with identical SMH values may occur, which is crucial for betweenness calculation.

$$K{P}_{(S\to T,C)}=\{{P}_{1},{P}_{2},\ldots ,{P}_{k}\}\quad \,\text{where}\,\quad k\in {{\mathbb{Z}}}^{+}$$(3)$$\begin{array}{ll}SM{H}_{(S\to T,C)}\,=\mathop{{\rm{argmax}}}\limits_{{P}_{i}\in K{P}_{(S\to T,C)}}\left(\frac{1}{| {P}_{i}| -1}\sum _{V\ne S,S\ne T}\left({H}_{(V,C)}\right)\right.\\\left.\qquad\qquad\qquad\quad\,\,\,\,-\,{H}_{(S,C)}\right)\quad \,{\text{where}}\,\quad (V\in {P}_{i})\end{array}$$(4)$$SMH{P}_{(S\to T,C)}=\{{P}_{i}| SM{H}_{(S\to T,C)}\}$$(5)Fig. 9: Schematic example illustrating changes in maximum-averaged-entropy values (SMH) alongside paths (SMHP), highlighting how the k-value influences optimal route selection. -

2.

The next step is to calculate ESIN(T, C) which depicts the average SMH from all Ss to a T through all SMHPs. Since integration represents the “to-movement” potential of a node, a higher integration value typically indicates a greater likelihood of arrival. Likewise, a larger ESIN for a given T implies that visitors with a preference for class C exteriors are more likely to reach T no matter where they start their journey within the network. Conversely, a lower ESIN value for a segment implies a reduced probability that visitors with this preference will arrive there. Equation (6) illustrates the calculation of T’s ESIN, where the SMHs from all non-T source nodes to T are averaged to represent the ESIN of T. Additionally, two key factors can significantly impact the ESIN value of node T—the IAM value of T, and its proximity to nodes with high ESIN values, as these nodes may contribute to higher SMH values. Hence, a segment may still attract high visitation if it is contextually located at the core among the well-connected to highly attractive neighboring segments, even if it lacks intrinsic appeal. On the other hand, a segment with significant appeal may still have a low ESIN if it is poorly connected or surrounded by segments with low IAM values. This indicates that, even with strong individual appeal, a location’s likelihood of being visited can be low if it is isolated or lacks integration within the network.

$$ESI{N}_{(T,C)}=\frac{1}{n-1}\sum _{T}\,\sum _{S,S\ne T}SM{H}_{(S\to T,C)}\quad \,\text{where}\,\quad (S,T\in G)$$(6)

During the computation of ESIN(T, C), the occurrence of traversed nodes along the SMH paths, denoted by the path set SMHP, is recorded to calculate ESCH(V, C), where V represents a node lying on the SMHP when moving from S to T. Equation (7) defines the ESCH of V, which is estimated by aggregating the occurrences of V in the context of multiple SMHPs, where σ(S→T∣SMH, C)(V) represents the number of SMHPs from S to T that passes through the intermediate V, while σ(S→T∣SMH, C) denotes the total number of SMHPs from S to T. Therefore, the ratio \(\frac{{\sigma }_{(S\to T| SMH,C)}(V)}{{\sigma }_{(S\to T| SMH,C)}}\) represents the proportion of the shortest paths from S to T that pass through V, and the summation indicates the V’s extent to be chosen as an intermediary node in the overall visitor wayfinding (concerning visitor preference class C) process across all source-target pairs in the network.

The ESCH metric corresponds to the “through-movement” concept, analogous to choice in SSM. A segment’s ESCH value is positively correlated with its likelihood of being selected by visitors with specific ERS preferences. Additionally, certain segments may experience higher selection frequencies, thereby shaping the structural framework of the network. The algorithm suggests that segments with higher intrinsic entropy (IAM) values or those acting as connectors between high-value segments are more likely to be chosen. These segments function as critical links within the network, facilitating movement and increasing exposure to visitor preferences. Notably, as the k-value increases, longer journeys can further enhance the likelihood of these IAM-advantaged segments being selected. Conversely, segments with low connectivity or isolation from high-value nodes may experience reduced selection probabilities, even if they possess intrinsic appeal. Additionally, a segment with a low IAM value but high connectivity to multiple other segments may fail to encourage further exploration, leading to the underutilization or neglect of certain regions despite their strategic position within the network. The exemplary computations of ESIN and ESCH are illustrated in Fig. 10.

The process begins by filtering out non-FH exteriors for each node. Next, the entropy value is computed under three circumstances, excluding the entropy of sources. For each “source-target” pair, the exterior with the maximum SMH is selected. These SMHs are then averaged to obtain the ESIN for the target. Finally, the normalized occurrence rate for each node is computed to derive ESCH values (this example focusing solely in scenario of V6 as the target). The orange dashed curves illustrate the constitution of each node’s occurrence rate.

Site description

This study focuses on the Chaozong district in Changsha, China, a historically significant area known as the provincial “Cultural-Historical District” (Fig. 11). Once a thriving market due to its location near an ancient port, Chaozong has undergone a continuous transformation, preserving historic buildings while adapting to modern needs. Some buildings have been officially designated as “Significant Relics Units under Protection” or “Important Historic Buildings” (Fig. 12) to preserve Chaozong’s authentic HI.

In 2018, local authorities launched a regeneration project, led by the Chengfa and Changfang Groups, aiming to transform Chaozong into a new fashion hub that integrates antiquity and modernity. The project is governed by the Regulations on the Protection of Famous Historical and Cultural City for Changsha City111, a statute aiming to protect historical features during redevelopment. However, due to fiscal pressures, especially in the post-COVID period, developers relaxed renovation restrictions in an effort to increase rental income. This shift heightened retailer enthusiasm for personalized exterior designs, resulting in a visually appealing but identity-obscuring transformation of Chaozong’s exteriors (Fig. 13).

Some facades lack historical accuracy, as seen in the two photos on the left, while the modernized white and green storefronts intentionally contrast with the authentic red-brick Jiu Ruli Mansion shown in the right photo. This alteration results from relaxed renovation regulations for private investors.

The study is focused on Chaozong for three main reasons: Firstly, its streets are lined with low-rise attached or semi-attached buildings, where exteriors are the predominant spatial attractors to influence visitor route choices (Fig. 13); Additionally, it typifies the gentrification trends seen across East Asian cities, where a distinctive blend of centuries-old landmark buildings (LBs) and privately renovated non-landmark buildings (NLBs) are often repurposed into fashion hubs featuring upscale restaurants and boutiques58; Furthermore, its ongoing revitalization efforts aimed at enhancing tourism, commercial, and residential functions, a trend common in many historic districts in China112,113 that face the risk of losing HI.

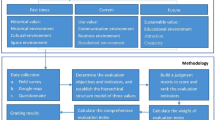

Research methodolgy

The empirical analysis of the case study consists of three main steps (Fig. 14) to examine the impacts of buildings renovated according to different ERS on VV. First, image-based check-ins, which serve as proxy data for vitality, are carefully filtered and georeferenced to the corresponding segments according to referred exteriors’ locations. The check-in counts for these segments serve as response variables, reflecting the extent of VV within these areas. These values will later be analyzed in relation to the vitality factors introduced in the second step. The SSMs are defined directly by the closeness and betweenness centralities in a graphic manner, without normalization (normalization is typically used in SS to compare metrics across different regions). In the next step, the computation of IAM, which measures the intrinsic attractiveness of a segment, is performed for 24 different visitor-preference scenarios (Fig. 7). These values are then input into the EAM algorithm to calculate the corresponding ESIN and ESCH. In total, the explanatory variables include 2 SSMs, 24 IAMs, 24 ESINs, and 24 ESCHs.

The final step involves importing proxy data as the response variable and factors (SSM, IAM, and EAM) as explanatory variables into a model for regression analysis. When computing EAMs, the k value in the k-shortest-path algorithm is critical, as it influences a segment’s extrinsic values by selecting different routes as k increases. However, increasing k can result in excessive detours, leading to attraction-led travel and reducing the impact of configurational factors. To address this uncertainty, the study uses thresholds from 10 to 150, with increments of 10 (the increment is set to balance model sensitivity and computational efficiency), resulting in 15 candidate thresholds for determining the optimal k values in both multivariate and univariate model fitting.

For model selection, since the response variable is check-in data, the non-negative, skewed count data does not follow a normal distribution which violates the assumption of homoscedasticity69. Therefore, simple and multiple linear regressions, assuming normally distributed residuals and constant variance, are not suitable for this study. Instead, GLMs, such as Poisson or Negative Binomial (NB) regression with a log link function, are more appropriate for modeling count data88. Furthermore, given the high dispersion rate σ2/μ = 57.05 (the value is extremely larger than 1, indicating severe overdispersion) (Fig. 16), the proxy data exhibit greater variability than expected under the Poisson distribution. These overdispersed observations apparently contradict the assumption of equidispersion in Poisson regression, where the variance equals the mean. Therefore, the Negative Binomial GLM (NB-GLM) is selected, as it is capable of addressing overdispersion by incorporating a dispersion parameter α that allows the variance to exceed the mean during model fitting.

To enhance the explanatory capacity of the NB-GLM, an automated optimization algorithm is developed to systematically reduce multicollinearity among predictors while simultaneously improving their statistical significance, as illustrated in Fig. 15a. This optimization procedure comprises two primary stages:

-

Preprocessing of vitality factors: All vitality factor values (IAM, EAM, and SSM) are normalized to a 0–1 scale by dividing each value by the maximum of its respective factor. This normalization ensures comparability across factors by placing them on a common scale, thereby allowing for more meaningful interpretation of regression coefficients in subsequent analysis. Prior to running the model, Pearson correlation coefficient analysis is employed to detect and remove factors contributing high multicollinearity. A threshold of 0.8 is empirically set to identify highly correlated pairs of variables. In each iteration, only the factor that exhibits the highest number of above-threshold correlation values in pairwise comparisons with other factors is eliminated. This process is repeated until all pairwise correlations fall below the threshold. Although the 0.8 cutoff is not a strict statistical criterion, it strikes a balance between retaining potentially significant predictors and avoiding excessive dimensionality. To be explicit, setting a lower threshold increases the risk of prematurely removing predictors that may hold substantive explanatory value during the NB-GLM fitting process. Conversely, given that the vitality proxy data includes only 39 segments (approximately half the number of the 74 candidate predictors), a higher threshold may retain an excessive number of variables, thereby introducing the “curse of dimensionality” and increasing the likelihood of overfitting, ultimately compromising the model’s explanatory power.

-

NB-GLM model optimization: This phase consists of two sub-processes. The first sub-process is a recursive elimination of statistically insignificant and collinear predictors. As depicted by the dashed square in Fig. 15a, the model fitting process initially removes the predictor with the highest p-value (≥0.05). This step is repeated until all remaining predictors are statistically significant. Subsequently, VIFs are calculated for the retained variables. The variable with the largest VIF value, which is also larger than 10, is removed, and the process recurs until all predictors satisfy the conditions of p < 0.05 and VIF ≤ 10. The threshold for VIF is defined according to Pardoe114 and Wooldridge115, who claims that a VIF of a predictor exceeding 10 is considered to pose problematic multicollinearity, possibly diminishing the reliability of model estimation. The second sub-process concerns the selection of the dispersion parameter α, which is critical for NB-GLM to manage overdispersed response data. As α must be specified in advance of the NB-GLM fitting, yet cannot be directly inferred from the data, a grid-search procedure is implemented to determine its optimal value which leads to the best model performance. For each candidate α scenario, the AIC is calculated and recorded after model fitting. After the grid search, the α that results in the lowest AIC is selected as the optimal dispersion parameter. To explain, AIC is chosen over alternative fit indices, such as log-likelihood, deviance, or Pseudo R2, as it is a more versatile criterion that penalizes model complexity while accounting for goodness-of-fit, in order to promote parsimony and mitigate overfitting. In contrast, the alternative indices primarily focus on goodness-of-fit without addressing model complexity, leading to imbalanced model performance.

a The workflow of optimizing the NB-GLM model, including preprocessing of vitality factor data, enhancement of model interpretability through the management of variables’ multicollinearity and statistical insignificance, and a grid search procedure for identifying the optimal dispersion parameter. b The determination of the optimal k shortest paths, aiming to identify the most suitable EAM values among various k-value scenarios that best enhance the NB-GLM's explanatory power with respect to vitality factors.

This automated algorithm substantially improves the efficiency of model optimization, enabling robust comparisons of NB-GLM performance across a wide range of k-shortest-step scenarios. Consequently, it provides a more objective basis for determining the optimal k-value in EAM computation.

In addition to the model optimization procedures illustrated in Fig. 15a, selecting an appropriate k-value is also critical for obtaining the optimal model, as variations in k can directly influence the identification of optimal routes (demonstrated in Fig. 9) and subsequently alter the values of EAMs. Similar to the dispersion parameter α, the optimal k-value cannot be predetermined without evaluating model performance post-fitting. Consequently, a range of EAMs under varying k-value scenarios is computed and incorporated, together with fixed SSMs and IAMs, into NB-GLM fitting for comparative evaluation. The NB-GLM that demonstrates the most satisfactory overall performance across multiple goodness-of-fit metrics—including AIC, deviance, log-likelihood, and pseudo R2—is selected as the optimal model, whose predictor weights (i.e., vitality factors) are then employed to interpret the VV manifested by the vitality proxy. The entire k-value determination process is illustrated in Fig. 15b.

Results

Current vitality distribution in Chaozong

Figure 16 illustrates the check-in volumes and spatial distribution of segments in Chaozong. The check-ins generally follow a power-law distribution, with over half concentrated on LS, SG, YQ, and BZ roads. LS stands out due to its authentic historic buildings (LBs), such as Jiu Ruli Mansion, Nanmu Hall, and several traditional residential structures, making it the area with the highest density of TH LBs. This has attracted private investors who rented and renovated NLBs, capitalizing on the area’s historic appeal. Despite LS being a historically sensitive area, financial pressures led to the relaxation of regulations, allowing diverse renovations that, while enhancing spatial diversity, diminished the original historical ambiance. SG and YQ feature modern facades with contemporary architectural styles (AH and NH), which have a strong visual appeal. BZ, although on the edge of the district, has a mix of counterfeited, adapted, or abstracted historic and modern buildings that contribute to a visually rich environment. CZ-5, a subsection of CZ Street, outperforms other areas in check-ins, thanks to its high-quality, reconstructed red-brick buildings that house well-funded brands. These brands have carefully designed their facades to integrate modern styles with the traditional red-brick exteriors, boosting their appeal. In contrast, segments such as CZL, XZ, SD, and YQBZ, while located near vibrant areas, show fewer check-ins. Though LBs on CZL and XZ have been protected, and some NLBs on YQBZ have been well renovated, these areas have not achieved the revitalization goals as expected. SD, a passage from BZ to the inner segments, has low check-ins, primarily due to ongoing construction nearby, which led to noise and dust, discouraging visitors. Additionally, the few renovated buildings in SD further reduced its appeal. On the edges of Chaozong (CZ, FQ, ZSXL, and ZSBL), the buildings are mostly unrenovated and lack historic charm, leading to fewer check-ins despite the busy flow of visitors.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis exploring the impact of renovated exteriors on visitor vitality primarily relies on the explanatory power and robustness of the NB-GLM model.

Since the optimal k-value cannot be predetermined, it is necessary to explore it empirically by calculating the EAM values across a range of k-value scenarios, prior to fitting them, along with IAMs and SSMs, into the NB-GLM, as illustrated in Fig. 15b. In this study, the k-value is set to range from 10 to 150 with an increment of 10. This range is selected based on preliminary observations indicating that values below 10 and over 150 tend not to yield optimal goodness-of-fit metric values—the trends can be inferred by Fig. 17. Besides, the increment of 10 is adopted to avoid overly fine-grained k-values that may lead to overfitting and increase computational complexity, thus preserving the model’s generalizability and its executional efficiency.

The goodness-of-fit metrics a AIC, b deviance, c log-likelihood, and d Pseudo R2 are presented across the 15 k values (10–150 shortest-path scenarios) on the x-axis. Each result is derived under the condition that, for each corresponding k-shortest-path scenario, the lowest AIC value was achieved using the method described in Fig. 15a.

To elaborate, for each k-value, the NB-GLM is independently optimized through grid-searching for the dispersion parameter α contributing to the lowest AIC, and subsequently, the key goodness-of-fit metrics, not only AIC, but also deviance, log-likelihood, and Pseudo R2, are recorded to more comprehensively inform later model selection. These metrics adhere to two criteria for assessing model performance—lower values of AIC and deviance indicate better model fit, and higher values of log-likelihood and Pseudo R2 reflect improved explanatory power. As Fig. 17 shows, the minimum AIC occurs when k equals 40, which also corresponds to the peak values for log-likelihood and Pseudo R2 in the NB-GLM. The trends in all subplots suggest that increasing k does not improve the model performance, as further k-value increases do not seem to yield promising values of indices. Except for the deviance, overall, 40 is the optimal k-value for limiting the number of shortest paths used in EAM calculations, and in such circumstances, the AIC approaches the lowest value when α for NB-GLM is close to 0.384.

Apart from the multivariate analysis, a univariate analysis is performed to evaluate the influence of individual predictors on vitality. This analysis aims to compare the interpretability of SSMs, IAMs, and EAMs at the univariate level and contrast their performance with the multivariate model.

Figure 18 presents the univariate NB-GLM fitting results for the four metrics used in the multivariate model. The gray lines in all subplots represent IAMs and EAMs across different k-threshold scenarios, while the red and blue straight lines correspond to SSMs (integration and choice). The orange points indicate the metric values from the optimal multivariate model (k = 40). Integration and choice show relatively low explanatory power in capturing vitality distribution across Chaozong segments, as fitting results exhibit high AIC and deviance, and extremely low values of the other two metrics. While most IAMs and EAMs perform significantly better than SSMs—especially the IAM related to high visual quality (High-quality Entropy) and the EAM (High-quality ESCH)—their performance still pales compared to the comprehensive results of the multivariate model.