Abstract

In the Qin River Basin—a cultural heritage cluster in southeastern Shanxi—existing studies predominantly focus on individual heritage valuation, with limited examination of spatial connectivity patterns. This study examines heritage corridor construction in the Qin River basin using the MCR model’s least-cost path analysis and Circuit model from the Linkage Mapper toolbox. Applying the gravity model, we identified and classified corridors, ultimately selecting high-suitability routes. Key findings include (1) Integration of heritage “source” raster data with resistance surfaces generated 53 potential corridors (total length: 578.48 km); (2) Gravity-based classification yielded 4 primary, 5 secondary, and 12 tertiary corridors; (3) The macro-level network builds a “two vertical-one horizontal” pattern centered on Runcheng Town and Qinyang City, At the micro-level, a multi-dimensional “corridor-station-source” system is constructed to connect heritage nodes through corridors and use key areas as stations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As a material witness of human civilization, the protection mode of cultural heritage is undergoing a paradigm transformation from “dotted islands” to “linear networks”. However, the city has faced challenges in preserving its cultural heritage amidst rapid development in recent years. Urban construction often encroaches on heritage sites, while land development impacts the ecological environment1. China is experiencing widespread industrialization and unprecedented increases in urbanization. In the current process of rapid urbanization, scattered cultural heritage sites are generally facing the dilemma of “islanding”, which leads to the lack of historical context due to spatial fragmentation, and isolated conservation strategies are difficult to cope with the combined pressure of ecological erosion and tourism development. Heritage corridors, as a collection of green way sand heritage areas, are a new type of conservation approach2. It is a new model that emphasizes linear connection and overall protection, and provides a new way to solve the “island effect” of cultural preservation units by connecting scattered heritage nodes and integrating ecological resources along the route. Heritage corridors play a pivotal role in preserving linear cultural heritage, especially in economically underdeveloped regions like the Yellow River area3. This conservation concept has shown significant ecological and cultural synergies in cases such as the Rhine Valley Heritage Corridor and China’s Grand Canal.

The widespread distribution of cultural heritage in the Yellow River region emphasizes the need for targeted protection and utilization at the regional level. As an important fulcrum of the Yellow River civilization, the Qin River Basin presents unique spatial characteristics of cultural heritage. There are 43 military heritages such as the ruins of the Great Wall of the Ming Dynasty and the ancient castles of Douzhuang, 27 traditional villages such as Guobi and Xiangyu, and ancient water conservancy engineering systems such as Fangkou Weir and Guangli Canal, which together constitute the testimony of the composite function of “fort joint defense and Caoyun irrigation” from the Song, Yuan and Ming dynasties to the Ming and Qing dynasties4. However, field surveys show that 78.6% of these sites are more than 5 kilometers away from the nearest peer node, and 34% of the ancient villages are at risk of building collapse due to population loss. This spatial dispersion and fragmentation of management severely restricts the overall interpretation and sustainable use of heritage values.

The Yellow River is not only an important ecological barrier, but also one of the birthplaces of Chinese civilization, which boasts abundant cultural heritage resources. However, existing research on the evaluation of a cultural heritage resource value and the construction of heritage corridors in this region is relatively scarce5. The current regional, segmented, and unit-based protection models have resulted in the fragmentation and isolation of heritage conservation efforts6. For instance, studies on the Qinling Mountains highlight how administrative divisions disrupt ecological and cultural continuity, with localized policies often prioritizing economic development over holistic heritage integration7,8. Yu and Zhu have critiqued this siloed approach, emphasizing that the lack of cross-regional coordination weakens the systemic protection of linear heritage networks (e.g., ancient trade routes, hydrological systems) and fails to address ecological-cultural interdependencies9,10. This study verifies the cross-regional integration potential of cultural heritage corridors through the Qinhe River Basin, providing methodological support for overcoming fragmented protection due to administrative divisions. Constructing graded heritage corridors is crucial for fostering the coordinated development of the cultural tourism industry in the area. It is planned to connect heritage corridors to important cultural heritage nodes to form a linear cultural heritage network, and heritage corridors can rely on natural and artificial passages such as rivers, ancient roads, and transportation arteries. The Plan for the Protection and Utilization of Cultural Heritage in the Yellow River clearly puts forward the goal of “building cultural identification corridors and strengthening the spatial association of heritage”. As one of the basins with the highest density of Chinese heritage in the first-class tributaries of the Yellow River, the construction of heritage corridors in the Qin River is not only related to regional cultural and ecological security, but also a key practice site for the implementation of the strategic deployment of “bringing the Yellow River culture to life.

Since the 1960s, the concept of the greenway has matured, and with the development of heritage conservation towards regionalization11. Heritage corridors, as a collection of greenways and heritage areas, are a new type of conservation approach. This conservation direction integrates several concepts such as heritage of various cultural landscapes at the regional level. Corridors are usually characterized by economic development, tourism, adaptive reuse of heritage, and recreational environment improvement12.

Fristly, the research on existing heritage corridor mostly focuses on the identification of single cultural lines or ecological corridor design, which has limitations.76% of the cases in the existing literature focus on artificial linear heritage such as canals, ancient roads, and railways, and there is a lack of attention to organic growth corridors based on natural watersheds. For example, Spain’s vías verdes program repurposed 2500 km of obsolete railways into greenways, demonstrating a territorial strategy that prioritizes human-engineered infrastructure over organic, riverine networks13. In China, studies on the Ancient Tea-Horse Road and Ming Great Wall corridors reflect similar biases, relying on GIS and network analysis to map linear cultural routes while underrepresenting natural hydrological systems, whose ecological degradation has fragmented both cultural and biological connectivity14,15,16.

Secondly, there is a gap in the application of circuit theory in heritage corridors. Various methods of corridor generation have been applied in China and other countries, such as the qualitative analysis method17,18,19, the analytic hierarchy process20,21 and the minimum cumulative resistance (MCR) model22,23,24. Li et al. used the AHP or entropy method to evaluate the weight of resistance factors for corridor construction, and determined the comprehensive resistance surface through spatial analysis and the minimum cumulative resistance model (MCR) in GIS to generate the optimal route25. As the most prominent method to construct heritage corridors. The research method of heritage corridor construction takes MCR (minimum cumulative resistance) as the mainstream, but the coupling consideration of circuit theory is insufficient26. Circuit theory is currently widely used in research articles on ecological connectivity, but there is a lack of research on the construction of heritage corridor networks. Compared to the minimum resistance model that relies on a single optimal path, circuit theory can identify multi-path networks and key “bottleneck” areas. At present, there are some articles from both China and other countries that use this method to construct heritage corridors22,27,28. Wei et al. combined hydrological analysis and circuit theory, and introduced the entropy method to quantitatively evaluate the importance of corridors, identify key nodes and corridors, and generate comprehensive resistance surfaces by weighted superposition29.

Thirdly, the existing research has primarily focused on the categorization of ecological corridors30,31,32 while ignoring the classification of heritage corridors. Certain studies have proposed a hierarchical classification of heritage corridors based on the level of connectivity27,33 or the suitability of heritage distribution and corridor construction34. For instance, studies on the Taihu Lake heritage network proposed a “double main rings, multiple branches” spatial pattern but did not differentiate corridors by heritage significance or tourism potential35,36. In contrast, the Qin River Basin’s graded corridor plan—prioritizing high-value heritage clusters for preservation while developing low-value sites for cultural tourism—offers a replicable model for balancing conservation and utilization. For high-value cultural heritage, the primary emphasis lies on preservation and restoration, accompanied by the judicious development of tourism initiatives. Conversely, low-value cultural heritage involves the exploration of cultural elements based on the value hierarchy of cultural heritage. The gravity model (a quantitative method) is adopted to conduct hierarchical assessments, identifying primary and secondary corridors that facilitate the connectivity of high-value cultural heritage source areas. With the promotion of the ecological protection and high-quality development strategy of the Yellow River, many villages in the basin have begun to be renovated to strengthen the ecological environment and the common development of economy and society. However, over-commercialization has led to the loss of authenticity of some heritage sites (e.g., the excessive conversion of Douzhuang Castle into a commercial district)37. In recent years, attention has been paid to the protection of cultural heritage, and a series of projects for the protection of the natural environment and heritage have been formulated and carried out. However, due to the lack of effective spatial connections between heritage sites, the historical context is broken, and the interpretation of cultural values is limited, and the protection and development of heritage are still under potential threats. Therefore, this study took the Qin River Basin as the study area. This study aims to construct a cultural heritage corridor network through circuit theory. (1) Identifying heritage clusters in the basin, employing the MCR model to establish a comprehensive resistance surface and delineate suitability zoning. (2) applying circuit theory to simulate spatial accessibility, ultimately determining optimal corridor routes with tourism stations as key nodes. (3) classifying the heritage corridor types with the gravity model.

Methods

Overview of the study area

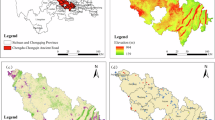

The Qin River is a major tributary of the Yellow River, and the townships that flow through it are the specific study area (Fig. 1), which spans the provinces of Shanxi and Henan. It originates from Heicheng Village, Pingyao County, Shanxi Province, from north to south, from Changzhi City and Jincheng City, crosses the Taihang Mountains, originates in the suburbs of Jincheng City (Zezhou County), flows into Henan Province through Zibaitan in Jiyuan City, flows through Jiaozuo City, and finally joins the Yellow River in the south of Wuzhi38. The topography of the Qin River Basin is high in the north and low in the south, and in the valley basin, the Qinshui Basin is formed in the upper reaches and the Jincheng Basin is formed in the middle reaches. On the whole, there are many mountains and hills in Shanxi, and the northern plains of Henan are the mainstay. The basin is rich in ecological resources, dense alpine forests, fertile soil in the river valley, and rich in cultural characteristics in the Qin River Basin, which has a profound historical and cultural heritage, as well as a unique folk culture and ecological environment.

Data sources and preprocessing

The data mainly come from the following aspects: (1) eight batches of national key cultural preservation units announced by the State Administration of Cultural Heritage, eight batches of provincial key cultural preservation units announced by the Shanxi Provincial and Henan Provincial Cultural Heritage Bureaus, (2) six batches of national traditional villages announced by the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development; (3) Municipal cultural protection units announced by the people’s governments of Jincheng City, Qinyang City, Jiyuan City and other places (excluding Anze County); (4) Seven batches of famous historical and cultural towns and villages in China announced by the State Administration of Cultural Heritage, and famous historical and cultural towns and villages announced by the people’s governments of Shanxi Province and Henan Province; (5) The vector data of artificial environment elements such as highways, railways, and political maps come from the national geographic information resource directory service system; (6) A total of 16,781 POIs for public services are from the Baidu Map Open Platform; (7) Raster data of spatial distribution of topography, landform, temperature, precipitation, etc., downloaded from the official website of the National Earth Data Science Center; (8) Vector data such as administrative divisions and satellite cloud maps downloaded from the official website of the geo spatial data cloud.

Kernel density analysis

Nuclear density analysis is a probability density function for estimating spatial elements in a specific range. It transforms discrete point elements into a continuous density surface and is used to analyze the distribution characteristics of elements in space. A greater kernel density value f(x) indicates a higher degree of aggregation39.

In the formula, n is the number of points in the threshold range; x-xi represents the distance between two points; h is the estimated radius; K is the kernel function; the larger the value, the more clustered the spatial distribution of the legacy.

Minimal resistance model

The minimum cumulative resistance model (MCR)was first proposed by Knappen as a model to measure the spatial cost of species transfer from ecological source areas to other areas28. The model calculates the pathway with the least cumulative resistance in space by constructing a resistance surface to provide the best pathway for species migration dispersal and energy flow40.

In this process, different environmental elements have different resistance values. The larger the resistance value, the less suitable for activity, and the path with the least cumulative resistance is the most suitable channel for rest. The model formula is as follows:

In Ri represents the resistance of the site to the heritage rest activities in the heritage corridor; Dij represents the distance between the environmental element j and the source point. The suitability of heritage corridor construction was classified into five tiers using natural breaks (Jenks) based on MCR values derived from GIS cost-distance analysis (Table 1).

Circuit theory

Circuit theory compares species dispersal in landscape ecology to electron motion in physics and treats landscape elements not suitable for some ecological processes as regions41 with high resistance, low electron flow probability, and low current density. In the Circuit theory, when elements such as heritage resources, cultural nodes, or path networks are constantly changing (such as terrain changes or land use changes), they will affect the flow path of current, and thus affect the connectivity and structure of the entire network42. Therefore, Circuit theory is particularly suitable for annular areas, forming a surrounding path and constructing a traditional village heritage corridor with a “center–enclosure” pattern43. Through this study, the occurrence probability of legacy rest activities was analyzed, and the Pinchpoint Mapper tool of the LM plug-in was calculated.

This study uses circuit theory to construct heritage corridors, treating spatial barriers between cultural heritage nodes (such as terrain, urbanization, and transportation networks) as “resistance”. The greater the resistance, the poorer the connectivity between nodes. Simulate the “cultural flow” between cultural heritage elements (such as historical transmission paths, population migration routes), with high current areas representing key corridors or protection priority areas. The construction of a Circuit theory-based heritage corridor requires the calculation of the current density Ji. This paper uses a current distribution model, setting the current threshold at 500, the voltage difference threshold at 10, and the connectivity threshold at 3. Based on these thresholds, it is possible to identify nodes with higher cultural value and greater foot traffic, which should be prioritized for protection or development.

Among them, Ji is the current density of the i area, that is, the potential of heritage activities. wk is the weight of each influencing factor, and fik is the score of the i region under the k factor. Ri is the resistance value of the i area, that is, the resistance surface data generated by ArcGIS.

The gravity model

The gravity model provides an important tool for urban and rural planning and resource allocation by simulating spatial interaction relationships. The interaction intensity between the sources of heritage corridors was quantitatively evaluated, and the interaction matrix was constructed by using the gravity model, and the stronger the interaction between the sources and the more important the connected heritage corridors were. According to the actual research situation, the importance of each heritage corridor is judged and divided into three heritage corridors44. The gravity model formula is as follows:

where Gij represents the magnitude of the interaction force between sources; Dij represents the magnitude of resistance between potential corridors; and Lij represents the value of cumulative resistance between sources.

Results

Screening and determination of heritage “source place”

Through a systematic analysis of cultural heritage units in the Qin River Basin, our investigation identified a total of 452 protected cultural units, including national, provincial, and municipal-level sites. However, due to issues such as inaccurate or missing coordinate annotations in municipal-level units, coupled with the requirement of kernel density analysis for a sufficient sample size and spatial aggregation characteristics, the exclusion of municipal-level sites was necessitated. Their isolated distribution or weak cultural relevance would hinder the formation of a closed-loop network structure, thereby compromising the overall efficacy of the corridor. Consequently, this study selected 177 cultural heritage units for analysis, comprising 90 nationally protected heritage sites and 87 provincially protected sites (Table 2). Applying China’s Heritage Recreation Evaluation Standard45 (GB/T) to assess recreational potential, these units were categorized into five hierarchical tiers based on their functional scores. Following the exclusion of the lowest-rated “first-level resource points” (per national classification criteria), 156 cultural preservation units were ultimately selected as core heritage resources for further development. From the distribution map generated by GIS kernel density analysis (Fig. 2), it can be seen that Runcheng Town in Yangcheng County is the central point, forming the part with the highest concentration degree and the largest agglomeration range in the study basin. In addition, with the southeast of Qinyang City, Henan Province as the central point, the core area is mainly concentrated in Qinyang City, forming a sub-center. With Tuwo Township in Qinshui County and the southwest of Jiyuan City in Henan Province as the central points, a small core area has been formed. In conclusion, from the distribution of the spatial kernel density of the tangible cultural heritage in the Qin River Basin, it is found that the distribution of the heritage has obvious river basin characteristics, which are generally concentrated in the middle and lower reaches of the Qin River Basin, which is richer in ecological and cultural resources. A spatial pattern was formed, centered on Runcheng Town in Yangcheng County and Qinyang City in Henan Province, and spread out to the surrounding areas46. Finally, due to the polycentric agglomeration of cultural heritage sites in the region, the scale of cultural heritage monomers is too small, and the areas with high agglomeration degree are designated as first-class sources, and medium- and medium high density are second-level sources (Fig. 3).

Comprehensive resistance surface construction

In this paper, the resistance surface of the cultural heritage corridor is constructed as the benchmark, and the topographic undulation, slope, and distance according to the river are selected as the resistance factors to construct a single-factor resistance surface. In this study, we used a hierarchical analysis method to determine the weights of resistance factors, and the hierarchical analysis method helps decision-makers to make trade-offs and choices between multiple criteria and alternatives by breaking down complex problems into hierarchies. With the help of YaaHP software, for each level, input the constructed judgment matrix to compare each factor in pairs, and visually display the hierarchical structure and weight results. ArcGIS was used to classify and standardize the resistance factors, and the resistance values were divided into five levels47. The 14 resistance factors selected from the three aspects of natural environment, social economy and public services were weighted and superimposed to complete the construction of the comprehensive resistance surface (Fig. 7 for the construction results of the comprehensive resistance surface, and Table 3 for the categories, grades and weights of each factor).

In terms of the natural environment, it is necessary to follow the principle of ecological protection in the Qin River Basin, and to minimize the anthropogenic disturbance to the natural landscape in the planning of heritage recreation activities. Three-dimensional terrain factors such as elevation, slope and topographic undulation are positively correlated with spatial resistance, and the suitability of the corresponding area decreases by 15%-20% for every 10% increase in terrain complexity. A high vegetation cover index indicates that the ecosystem is fragile and ecologically sensitive. Activities in these areas may have a greater impact on the ecological environment, so the suitability of the activity is low; Areas farther away from water sources are less ecologically sensitive and less disturbed by anthropogenic activities, making them more suitable for heritage recreation activities (Fig. 4). Resistance values reflect the suitability of different land use types for recreational activities48. Low-resistance areas, such as developed tourist areas, roads, squares, etc., have well-developed infrastructure and are suitable for high-intensity recreational activities. Areas with high resistance values, such as forests, wetlands, nature reserves, etc., are ecologically sensitive and suitable for low-intensity ecological experience activities. The higher the activity intensity, the greater the ecological pressure on the area, so it is necessary to select the area with low resistance value to reduce the impact on the ecological environment.

In terms of socio-economic aspects, nighttime light data can measure the level of economic development of a region (Fig. 5). Based on the theory of spatial heterogeneity, the nighttime light index (NTL) was used to quantify the level of regional economic development, and its spatial empowerment effect on heritage leisure activities was revealed: the NTL index was significantly positively correlated with the suitability of leisure activities (R² ≥ 0.72), and the high-vitality area with light intensity higher than 35nW/cm²·sr could carry supporting functions such as tourist service center and cultural and creative commerce. Therefore, a high nighttime light index indicates that the economic vitality of the region is high, which is conducive to the development of rest and entertainment-related services. In terms of traffic conditions, within 5 ≤ 00 m of the national/provincial highway, the accessibility of the leisure node is increased by 40%, and the resistance coefficient is attenuated by an exponential function. The county road and the rural road focus on improving the “last mile” connection through the addition of greenway connection points. In addition, there are significant differences in the spatial accessibility of different levels of roads, and optimizing the structure and quality of roads is the key to improving regional spatial accessibility.

In terms of public services, Kernel Density Estimation (Kernel Density Estimation) identifies hot spots in service clusters, and the area with a density value of >5.2/km² forms a composite service core, and the spatial constraint coefficient is reduced to 0.25–0.45, and the lower the resistance value, the more conducive to the development of heritage recreation activities. By analyzing the spatial distribution characteristics of service facilities such as accommodation, catering and scenic spots in the study area, the higher the kernel density value, the stronger the agglomeration of public services, the better the related service capacity, and the smaller the resistance value. When the spatial coupling degree between the POI and the catering facilities in the scenic area reaches 0.68, the attenuation rate of the resistance value increases (Fig. 6).

The above 14 resistance factors, including elevation, slope, river, road, catering spots, etc., were superimposed and analyzed according to the weight coefficients, and the comprehensive resistance surface of the comprehensive heritage corridor was calculated, and the range of the comprehensive resistance value in the study area was 1.7–7.5, and the average resistance was about 4.6, indicating that the formation of the heritage corridor as a whole faced a moderate degree of resistance. By identifying areas of low resistance, it is possible to provide optimal path selection for the planning of heritage corridors, reduce construction and conservation costs, and consider the protection of areas with high resistance during the construction process, and take corresponding protection or bypass measures (Fig. 7).

Construction of the heritage corridor network system in the Qin River Basin

The corridor development of the river basin is highly suitable for the development of corridors, which are distributed alternately along the Qin River from north to south, and have obvious river basin characteristics. The middle and lower reaches of the Qin River Basin are more adaptable to the construction of heritage corridors than those in Anze County, mainly including: Jiafeng Town, Runcheng Town, Beiliu Town, Fengcheng Town, Jiyuan City, and Qinyang City. The area presents the geomorphological characteristics of the river valley plain, with small topographic fluctuations, superior ecological environment conditions, and low spatial resistance. It is worth noting that the high, medium and high suitable areas have obvious linear characteristics in terms of spatial distribution, which are highly consistent with the direction of traffic arteries, indicating that traffic conditions have an important impact on the layout of heritage corridors and constitute the core components of the potential heritage corridor network. In general, a corridor structure with the Qin River Basin as the main axis was formed in the study area.

Using the LM plug-in, a potential heritage corridor network was generated by combining the heritage “source” ground and the comprehensive resistance surface raster data. The result is a potential 53 heritage corridors with a total length of 578.48 km. As can be seen from Fig. 8, the resulting corridor network is a network structure that diverges outward from Runcheng Town and Qinyang City as the core areas (such as the Jiafeng section, the middle and lower reaches of the Qin River), and this structure enhances the overall connectivity and resilience of the corridor network. Among them, the valley corridor in the middle reaches of the Qin River takes the first-class source as the core, forming a clear network, and at the same time, the cultural heritage here is dense, and the distribution spacing is small, which is easy to connect. In the south, a cultural-ecological corridor in the lower reaches of the Qin River is formed along the main road from east to west, and the two cores are connected by multiple branch lines, strengthening the north-south connectivity.

The top 15 heritage “sources” with high agglomeration were selected as the research objects, and these “source” sites had higher heritage value and more concentrated distribution. Based on a gravity model, the G-values between each pair of sites are calculated, quantifying the intensity of the interaction between them. Corridors are graded according to their G-values, with higher G-values indicating greater interaction and greater importance of connectivity between the two sites. It is often the core connecting path of a heritage network and has important ecological, cultural and economic value. Priority should be given to protecting and enhancing its connectivity. Based on this, the interaction forces between the core sources were calculated, and some redundant corridors were manually eliminated with reference to the threshold setting of related studies49. The specific grading standards are as follows: corridors with force values greater than 3000 are defined as first-class corridors, a total of 4; G value 1000–3000 is a secondary corridor, a total of 5; G value 300–1000 is a three-level corridor, a total of 12. Based on this, the patch interaction matrix (Table 4) and the ecological corridor network in the Qin River Basin (Fig. 9) were constructed.

As can be seen from the figure, the first-class corridor is mainly concentrated between Jiafeng Town and Runcheng Town, and belongs to the valley corridor area in the middle reaches of the Qin River. The cultural heritage in this area is densely distributed, including Xiangyu Castle, Douzhuang Castle, Guobi Ancient Village, etc., and the heritage sites are relatively small and easy to connect. In addition, the terrain of this area is flat, belonging to the river valley plain landform, the ecological environment is superior, and the spatial resistance is low. The economy of the towns along the route is active, the infrastructure is perfect, and the feasibility of corridor construction is high. In contrast, the distribution of low-grade corridors is relatively scattered, indicating that the construction of heritage corridors in these areas faces greater resistance, further highlighting the necessity of high-grade corridor construction. The area where these high-grade corridors are located is not only the core area of culture and economy, but also has a smooth transportation network with the surrounding areas, close cultural relations and frequent exchanges, which has laid an important foundation for the construction of regional heritage corridors in the future.

The critical access areas are usually the bottleneck area in the heritage corridor network. The obstacle points of the heritage corridor are mainly spatially distributed near the cultural preservation units and around the urban land. With the Circuitscape in GIS, a total of 16 obstacles were identified, among which 10 were located on important corridors and were key obstacles that needed to be accurately identified and solved later (Fig. 10). These areas are hampered by anthropogenic activities (e.g., urban sprawl) or natural conditions (e.g., topographical barriers). It is necessary to take protection and restoration measures for the obstacle points, i.e., cultural preservation units and traditional villages, to reduce the interference caused by tourism development.

Starting from the spatial distribution of cultural heritage, this paper analyzes the current situation of spatial agglomeration of cultural heritage preservation units, takes the core agglomeration area of cultural heritage preservation units as the “source” of cultural heritage, constructs the heritage corridor with the least resistance model, identifies the spatial agglomeration characteristics of cultural heritage through kernel density analysis, and determines the area with a high concentration of cultural heritage units as the “source” of cultural heritage (Table 5). Relying on national-level traditional villages and cultural preservation units, we will build corridor “post stations”, and select those traditional villages with high cultural value, profound historical heritage and suitable geographical location as “post stations”. At the same time, these villages should have a high current density, i.e. on the barriers of the heritage corridors, to facilitate the dissemination and exchange of cultural heritage. These “post stations” can not only serve as places for the protection and display of cultural heritage, but also provide tourism services, cultural experiences and other functions, and enhance the vitality and sustainability of the cultural heritage network. At the same time, it can be displayed around the national cultural heritage within 5 km around the post station and the corridor, highlighting its own characteristic industries.

It can be seen from the chart that the “post stations” are mainly concentrated in Jiafeng Town, Runcheng Town, Fengcheng Town, Beiliu Town and Qinyang City, but there are obvious differences in the distribution of their hierarchical characteristics, and most of the first-class “post stations” are located in the middle reaches of the Qin River. In general, the “source” and corridors of the divergent heritage network centered on Runcheng Town in the middle reaches of the Qin River are of high grade and concentrated distribution, forming a cultural heritage network with a high degree of integration. The “source” of the Jiyuan-Qinyang section of Henan Province has a high-grade corridor and maintains a single east-west direction (Fig. 11). However, the poor connectivity of the two corridors is mainly due to the differences in the cultural relics protection norms between Shanxi and Henan provinces, and the failure to receive the attention of the relevant cultural protection departments, and the failure to form a unified cultural heritage corridor. The construction and optimization of the heritage corridor network system in the Qin River Basin is a systematic project, and its core lies in realizing the coordination of the protection, utilization and regional development of cultural heritage through the multi-level network structure of “corridor-station-source”. This system not only provides a spatial foundation for the protection of cultural heritage, but also builds a macro platform for cultural tourism, ecological experience and other activities. Through scientific planning, rational utilization and multi-party cooperation, the value of protection and utilization will be further enhanced, and new vitality will be injected into the sustainable development of regional culture and ecology.

Discussion

Current research on heritage corridors has generated substantial theoretical and practical advancements, particularly in exploring their structural composition, spatial evolution patterns, and interdisciplinary policy frameworks. Academic contributions have emphasized the significant role of cultural corridor construction in promoting regional development50. This study innovatively addresses three persistent challenges identified in existing literature: (1) spatial fragmentation of heritage resources. (2) administrative boundary constraints. (3) the utilization-protection paradox. Through an integrated methodological approach combining circuit theory-based network simulation, gravity model hierarchy assessment, and composite resistance surface modeling incorporating natural-anthropogenic factors, we propose a systematic solution framework. The research employs spatial analysis techniques to quantify connectivity patterns while establishing an evaluation system that balances ecological preservation with cultural sustainability. Compared to traditional methods, the constructed” corridor-station-source”; system not only enhances the connectivity of the heritage network but also achieves a dynamic balance between protection intensity and utilization intensity through hierarchical strategies, providing a replicable approach for the construction of a “cultural-ecological community” in the Yellow River Basin. Specifically, there are the following points:

Firstly, the design of closed-loop networks plays a strong supporting role in cross-regional protection. This study couples the natural hydrological system of the Qin River Basin with cultural heritage nodes to construct a “two vertical and one horizontal” networked corridor, breaking away from the traditional reliance on artificial linear heritage13,14,15,16. The application of circuit theory results in a closed loop structure for the corridor network, better aligning with the natural connectivity of the basin’s ecology and culture, echoing the need for an “organic growth corridor” mentioned in the introduction The multi-dimensional hierarchical system proposed in this paper makes up for the lack of cultural value stratification in the “double main ring and multiple branches” structure of Taihu heritage network35,36, and provides a scientific basis for differentiated protection strategies. This approach integrates the Qin River Basin into a corridor system interconnected through cultural heritage51, emphasizing the spatial relationship between heritage distribution and corridor networks, which aligns with the principle of “trans-regional conservation and utilization of heritage corridors52”.

Secondly, existing studies often use the Minimum Cumulative Resistance (MCR) model for corridor generation25,31, but this method has limitations in addressing network closure design and multi-path optimization42,47. Circuit theory, by simulating the “current conduction” characteristics of cultural resources in space, provides a new paradigm for cross-scale network optimization the construction of heritage corridor, a closed loop was generated by using Circuit theory, it can be seen intuitively that the corridor generated by the Circuit theory shows obvious networking characteristics, forming a complete closed-loop structure, which accurately meets the needs of ring line design. The advantage of the Circuit theory lies in its path optimization capability based on the Circuit theory. By simulating the flow process of cultural resources in geographic space and comprehensively considering factors such as resistance and current density, a highly optimized spatial network is generated. However, after that, the gravity model is adopted to delimit the level of the heritage corridor, and it still needs to calculate the minimum distance and minimum resistance by using the MCR model.

Finally, unlike traditional studies that focus on natural factors such as elevation and slope, circuit theory offers a different approach. In the process of constructing the resistance factor selection and weight determination of the comprehensive resistance surface, YaaHP is used to construct the judgment matrix and score the resistance coefficient weight of the heritage corridor. After repeated discussion, the weight of each resistance factor is determined, and finally, the evaluation index system is constructed. Based on the determination of the suitability evaluation index system, this study adopted the minimum cumulative resistance model for the generation of heritage corridors. Unlike the corridors constructed by Ten et al. in the introduction53,54,55, which were based solely on natural factors such as terrain and slope, this study is the first to integrate socio-economic elements such as nighttime light index and dining and accommodation POIs (Figs. 5–6), making the resistance surface more closely aligned with the actual needs of heritage tourism. This aligns with Li et al.’s25 emphasis on “the coupling of humanistic and natural elements.

Although the results of the heritage corridor construction method obtained based on the minimum cumulative resistance model and the Circuit theory and kernel density analysis are reliable, this study still inevitably had some shortcomings:

First of all, inconsistencies in data accuracy were observed within the suitability evaluation index system. While high-spatial-resolution remote sensing data (e.g., 0.5–2 m resolution) provided precise spatial metrics, ancillary data from the National Geographic Information Resources Catalog Service System exhibited coarser granularity (≥30 m resolution). This methodological disparity introduced spatial uncertainty in corridor modeling, particularly affecting edge zones with abrupt landscape transitions.

Secondly, the initial inventory encompassed 452 cultural heritage sites across national, provincial, and municipal protection tiers in the Qinhe River Basin. To ensure data integrity, we prioritized the latest officially published heritage registries from the National Cultural Heritage Administration (2023 update) and provincial authorities. However, three critical constraints necessitated selective sampling: (1) temporal dynamics: Continuous updates to heritage registries (average 12% annual increment in Shanxi Province) rendered complete coverage unfeasible. (2) Data reliability: Municipal-level sites (n = 275) were excluded due to documentation gaps (23% coordinate inaccuracies per validation sampling) and relatively lower conservation urgency. (3) Spatial clustering efficiency: Kernel density analysis requires critical mass thresholds; dispersed municipal sites would distort cluster identification. Consequently, 177 nationally protected sites were retained for analysis, yielding 22 heritage source areas through optimized bandwidth parameterization (Silverman’s rule). Figure 8 illustrates the resultant corridor network derived via the Linkage Mapper (LM) plugin, with classification prioritizing the top 15 sources exhibiting the highest agglomeration density.

Finally, the gravity model implementation employed Minimum Cumulative Resistance (MCR) surfaces to compute inter-source distances. Two critical limitations emerged: (1) Operator-induced bias: Manual exclusion of 9% path segments showing abrupt resistance shifts lacked systematic criteria. (2) Classification subjectivity: The corridor importance matrix categorized levels based on resistance quintiles, yet threshold determination relied disproportionately on expert weighting versus empirical validation. We recommend that future studies adopt machine learning approaches to automate resistance thresholding, thereby enhancing objectivity. Supplementary Table 4 provides full parameterization details for reproducibility.

This study innovatively applied circuit theory to simulate the spatial transmission dynamics of cultural resources, overcoming the linear path limitations of traditional minimum cumulative resistance (MCR) models. By integrating current density mapping, we achieved closed-loop network design for cultural heritage corridors in the Qin River Basin. Key outcomes include the identification of 21 prioritized corridors and 10 critical bottleneck zones, alongside gravity model-based corridor classification. The resulting hierarchical “node-corridor-service station” spatial framework anchors 177 national and provincial heritage sites as cultural hubs, leveraging historical trade routes and modern transportation networks as spatial foundations. Service facility optimizations were proposed to enhance cultural information transmission efficiency in bottleneck zones. Strategic recommendations include: (1) Designing three thematic tourist routes to align heritage corridors with tourism infrastructure. (2) Establishing visitor centers and smart guidance systems at 10 bottleneck zones. (3) Implementing multi-scale “conservation-utilization” equilibrium policies in the Yellow River Basin, such as dynamic development intensity adjustments via current density early-warning mechanisms.

Future research should expand circuit theory applications to basin-scale analyses, particularly examining how socio-cultural factors influence “cultural current” transmission efficiency. This study not only validates heritage corridors as a viable solution to administrative fragmentation but also advances quantitative modeling tools for spatial governance of “cultural-ecological communities.

Data availability

The data generated and analyzed during the current study are provided in the manuscript and supplementary files.

References

Lin, H. et al. Historical sensing: the spatial pattern of soundscape occurrences recorded in poems between the Tang and the Qing Dynasties amid urbanization. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 11, 730 (2024).

Zhang, J., Jiang, L., Wang, X., Chen, Z. & Xu, S. A study on the spatiotemporal aggregation and corridor distribution characteristics of cultural heritage: The Case of Fuzhou, China. Buildings 14, 121 (2024).

Zhang, H., Wang, Y., Qi, Y., Chen, S. & Zhang, Z. Assessment of Yellow River Region Cultural Heritage Value and Corridor Construction across Urban Scales: a Case Study in Shaanxi, China. Sustainability 16, 1004 (2024).

Liu, C. & Xu, M. Characteristics and influencing factors on the hollowing of traditional villages-taking 2645 villages from the Chinese Traditional Village Catalogue (Batch 5) as an Example. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 12759 (2021).

Sui, Q. Research on the overall protection of the Yellow River Cultural Heritage from The Perspective of Cultural Routes. Int. J. Educ. Humanit. 5, 128–132 (2022).

Searns, R. M. The evolution of greenways as an adaptive urban landscape form. Landsc. Urban Plan. 33, 65–80 (1995).

Ren, L. & Lei, W. Research on the evaluation of ecotourism resources: based on the AHP model. Math. Probl. Eng. 7398537, 10 (2022).

Yu, K. H., Gong, J., Jing, Y., Liu, S. Q. & Liang, S. H. Theory to measure growth boundaries, planning, and regulation in the Qinling and Bashan mountain regions. Appl. Fractal 42, 116–119 (2017).

Yu, K. J., Xi, X. S., Li, D. H., Li, H. L. & Liu, K. On the construction of the national linear culture heritage network in China. Hum. Geogr. 4, 11–16+116 (2009).

Zhu, H., Zhao, R. & Xi, T. D. The protection research on lineal cultural heritages of Chinese Canal from cultural routes: a case of Anhui Section of Chinese Canal of Sui and Tang Dynasty. Hum. Geogr. 28, 70–73 (2013).

Ding, G., Yi, G. & Yi, J. Pueppke, Protecting and constructing ecological corridors for biodiversity conservation: a framework that integrates landscape similarity assessment. Appl. Geogr. 160 (2023).

Wang, Z. F. & Sun, P. Heritage corridors—a newer approach to heritage conservation. Chin. Gard. 5, 86–89 (1992).

García-Mayor, C., Martí, P., Castaño, M. & Bernabeu-Bautista, Á. The unexploited potential of converting rail tracks to Greenways: The Spanish Vías Verdes. Sustainability 12, 881 (2002).

Li, H. et al. Identifying cultural heritage corridors for preservation through multi dimension alnet work connectivity analysis—a case study of the ancient Tea-Horse Road in Simao, China. Landsc. Res. 46, 20 (2024).

Éndez, M. L., Lmo, R. M., Ruiz, R. & Yala, D. P. An interdisciplinary methodology for the characterization and visualization of the heritage of roadway corridors. Geogr. Rev. 106, 489–515 (2016).

Lin, F., Zhang, X., Ma, Z. & Zhang, Y. Spatial structure and corridor construction of intangible cultural heritage: a case study of the Ming Great Wall. Land 11, 24 (2020).

Zhang, D. Q., Shao, W. W. & Feng, T. Q. Discussion on construction of the Weihe River System Heritage Corridors in Xi’an Metropolitan Area. Appl. Mech. Mater. 641, 531–536 (2014).

Kashid, M., Ghosh, S. & Narkhede, P. A Conceptual Model for Heritage Tourism Corridors in the Marathwada Region. MrinalIn,K. Proceedings of the National Online Conference on Planning, Design and Management, Pune, India. 6–7 (Khaladkar Decorators & Events, 2022).

Hui, C., Dong, C., Yuan, Z. & Si, M. Construction of corridors of architectural heritage along the line of ZiJiang River in Hunan Province in the background of the Tea Road Ceremony. Dr Michael Thorne. In: IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 471, 082024 (IOP Publishing, 2019).

Li, H., Duan, Q., Zeng, Z., Tan, X. & Li, G. Value evaluation and analysis of space characteristics on linear cultural heritage corridors ancient puer tea horse road. Bian, F., Xie, Y. In: Proceedings of the Geo-Informatics in Resource Management and Sustainable Ecosystem: Third International Conference, GRMSE 2015, Wuhan, China, 16–18 October 2015 Revised Selected Papers 3, 733–740 (Springer, 2016).

Morandi, D. T. et al. Delimitation of ecological corridors between conservation units in the Brazilian Cerrado using a GIS and AHP approach. Ecol. Indic. 115, 106440 (2020).

Lin, F., Zhang, X., Ma, Z. & Zhang, Y. Spatial structure and corridors construction of Intangible Cultural Heritage: a case study of the Ming Great Wall. Land 11, 1478 (2016).

Li, Y., Wang, X. & Dong, X. Delineating an integrated ecological and cultural corridors network: a case study in Beijing, China. Sustainability 13, 412 (2021).

Zhang, L., Peng, J., Liu, Y. & Wu, J. Coupling ecosystem services supply and human ecological demand to identify landscape ecological security pattern: a case study in Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region, China. Urban Ecosyst. 20, 701–714 (2017).

Li, X., Zhu, R., Shi, C., Chen, J. & Wei, K. Research on the construction of intangible cultural heritage corridors in the Yellow River Basin based on geographic information system (GIS) technology and the minimum cumulative resistance (MCR) model. Herit. Sci. 12, 271 (2024).

Wang, Q., Yang, C., Wang, J. & Tan, L. Tourism in Historic Urban Areas: construction of cultural heritage corridor based on minimum cumulative resistance and gravity model—a case study of Tianjin. China Build. 14, 2144 (2024).

Li, H. et al. Identifying cultural heritage corridors for preservation through multidimensional network connectivity analysis—a case study of the ancient Tea-Horse Road in Simao, China. Landsc. Res. 46, 96–115 (2021).

Knaapen, J. P., Scheffer, M. & Harms, B. Estimating habitat isolation in landscape planning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 23, 10–16 (1992).

Wei, B. et al. Study on the comprehensive identification of ecological corridors and ecological nodes based on “HY-LM”. J. Ecol. 42, 2995–3009 (2022). (In Chinese).

Zhang, Y.-Z. et al. Construction and optimization of an urban ecological security pattern based on habitat quality assessment and the minimum cumulative resistance model in Shenzhen City, China. Forests 12, 847 (2021).

Feng, M., Zhao, W. & Zhang, T. Construction and optimization strategy of county ecological infrastructure network based on MCR and gravity model—a case study of Langzhong County in Sichuan Province. Sustainability 15, 8478 (2023).

Tang, F. et al. Linking ecosystem service and MSPA to construct landscape ecological network of the Huaiyang section of the Grand Canal. Land 10, 919 (2021).

Yue, F., Li, X., Huang, Q. & Li, D. A framework for the construction of a Heritage Corridor System: a case study of the Shu Road in China. Remote Sens 15, 4650 (2023).

Zhang, T., Yang, Y., Fan, X. & Ou, S. Corridors construction and development strategies for intangible cultural heritage: a study about the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Sustainability 15, 13449 (2023).

Mazzanti, M. Cultural heritage as multi-dimensional, multi-value and multi-attribute economic good: toward a new framework for economic analysis and valuation. J. Socio-Econ. 31, 529–558 (2002).

Wu, Y. et al. The research on the construction of Traditional Village Heritage Corridors in the Taihu Lake region based on the current effective conductance (CEC) theory. Buildings 15, 472 (2025).

Shi, K., Bi, Y. & Ren, C. Protect the overall beauty of historical stacking—Analysis of the spatial pattern of Douzhuang Castle in Qinshui County, Shanxi Province. Beijing Traffic Dly. 34, 128–132 (2010). (In Chinese).

Qin, X. Research on the overall structure and architectural characteristics of traditional villages in Qin River Basin under the influence of water environment (master’s thesis, China University of Mining and Technology) https://doi.org/10.27623/d.cnki.gzkyu.2022.001103 (In Chinese) (2022).

Hillier, B. Network effects and psychological effects: a theory of urban movement. Cohn, A. G., Mark, D. M. In: Proceedings of the 5th International Space Syntax Symposium, Delft, The Netherlands 13–17 (Springer, 2005).

Liu, X., Shu, J. & Zhang, L. Research on applying minimal cumulative resistance model in urban land ecological suitability assessment: As an example of Xiamen City. Acta Ecol. Sin. 30, 421–428 (2010).

Simon Elias Bibri, JohnK. Smart sustainable cities of the future: an extensive interdisciplinary literature review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 31, 183–212 (2017).

Zhang, L. X., Chai, B. & Zhang, Y. A comparative study on ecological networks based on MCR-Gravity model and circuit theory: a case study of Jining City. Ecol. Sin. 1, 13 (2025).

Yu, K. J. et al. Suitability analysis of heritage corridor in rapidly urbanizing region: a case study of Taizhou City. Geogr. Res. 1, 69–76 (2005).

Xu, F., Yin, H., Kong, H. & Xu, J. Construction of new town ecological network in central and western Brazil based on MSPA and minimum path method. J. Ecol. 35, 6425–6434 (2015).

Du, Y. F., Shi, C. Y., Tang, Y. & Chen, C. Research on the spatial construction of heritage corridors in the Yellow River Basin from a watershed perspective. Relics Museolgy 4, 103–112 (2024).

Jin, B., Xie, Z., Ke, S., Geng, J. & Pan, H. Construction and optimization of ecological corridor in Putian city based on MCR and HY models. J. Southwest Forestry Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 44, 79–87 (2024).

Ma, W. Research on line selection of Ganquan Long March Cultural Heritage Corridor based on MCR model (Xi’ an University of Architecture and Technology). Master’s Dissertation (2024) (In Chinese).

Wang, H. D. & Feng, X. Planning of slow-traveling facility system for the ancient great wall cultural heritage corridor in da tong, Shanxi province. Landsc. Archit. Front. 7, 18 (2019).

Jiao, J. Research on spatial-temporal differentiation and influencing Factors of Cultural Heritage in the Yellow River Basin. Master’s Thesis, Northwest Normal University, Master of Arts (2023).

Xu, H., Plieninger, T. & Primdahl, J. A systematic comparison of cultural and ecological landscape corridors in Europe. Land 8, 41 (2019).

Cheng, S. & Zhang, Y. The key to high-quality development of national cultural parks. J. Tour. 37, 8–10 (2022).

Wu, Q. & Wen, Y. A Dutch heritage policy for spatial planning in the 21st century. Famous Cities 36, 46–52 (2022).

Ten, Y. Xiaohe ancient road heritage corridor construction based on minimum cumulative resistance model. Planners 36, 66–70 (2020).

Yuan, Y., Xu, J. & Zhang, X. Construction of heritage corridor network based on suitability analysis: a case study of the ancient capital of Luoyang. Remote Sens. Inf. 29, 117–124 (2014).

Marques, L. F., Tenedório, J. A., Burns, M. & Romão, T. Cultural heritage 3D modelling and visualisation within and augmented reality environment, based on geographic information technologies and mobile platforms. Arch. Archit. City Environ. 11, 117–136 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51778610).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.L.: conceptualization, methodology, writing, software, validation, visualization; B.L. and Z.L.: methodology, data curation, validation, data curation, and funding acquisition. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, Z., Li, B. Circuit theory-based cultural heritage corridor network development in Qin River Basin. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 385 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01906-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01906-5

This article is cited by

-

Identification, evaluation, classification of the Chengdu-Chongqing Ancient Road cultural heritage corridor

npj Heritage Science (2025)