Abstract

This study examines the mechanical behavior of deep excavation pits in moist environments, using the Fenghuangzui site as a case study. We analyzed the effects of seasonal water level fluctuations on pit stability, combining archaeological, investigative, and field measurement data. Our results show that excavation-induced stress redistribution causes lateral movement of the side slopes, increasing with depth. Water level changes significantly impact pit stability. When the water level is above the bottom of the pit, local instability occurs due to the saturated soil layer slipping. Conversely, when the water level is below the bottom, bearing capacity failure leads to overall instability. To mitigate these issues, we recommend controlling water levels, improving soil stiffness and shear strength, and implementing anti-seepage measures. Enhancing foundation soil bearing capacity and stiffness is crucial for maintaining pit stability. These findings provide valuable insights for preserving archaeological sites in moist environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In humid environments, archaeological excavation pits are often destabilized and damaged due to high groundwater levels and heavy rainfall, leading to collapse and destruction after excavation. This not only results in the loss of valuable cultural layers but also poses a threat to the safety of archaeologists, causing significant difficulties for the preservation and utilization of important sites.

Prehistoric sites in humid environments within China are primarily found in the Yangtze River Basin, with notable examples including the Qujialing Cultural Site, Panlong City Site, Fenghuangji Site, Daxi Cultural Site, Hemudu Cultural Site, and Liangzhu Cultural Site. These sites exhibit similarities in their composition, typically comprising moats, fortifications, and settlement groups, reflecting a common pattern of ancient human habitation in this region.

The moat area of an archaeological site contains rich historical and cultural information, but its excavation is more challenging than other areas due to the depth of the excavation and the influence of groundwater changes1,2,3,4,5,6. Currently, the protection of dry soil sites has relatively mature technologies for anchoring and chemical conservation, while wet area excavations mainly rely on backfilling for protection, which severely limits the display and utilization of the site’s value. There is a lack of research on the destruction mechanism of deep excavations in humid environments, and scholars have used FLAC3D analysis software to study the stability of the Liangzhu Site excavation, providing a methodological basis for predicting the stability of excavations in humid areas7,8,9. However, the depth of the excavation in that study was only around 3 meters, and research on deeper excavations is still lacking. Currently, theories on slope and deep foundation pit stability analysis, reinforcement measures, and monitoring technologies have become relatively mature from a geotechnical engineering perspective10,11,12,13,14,15. From this viewpoint, the excavation of a moat area for archaeological exploration is similar to the excavation of a deep foundation pit. However, to ensure the integrity of the cultural layer information at the site, it is not possible to adopt the pre-reinforcement measures commonly used in deep foundation pit engineering. In light of these challenges, specialized and in-depth research is needed to address the safety and protection issues associated with archaeological excavations in moat areas of this type of site.

This article takes the Fenghuangzui Site, a prehistoric site in the Jianghan River Valley, as its research object and combines soil properties with field measurements to analyze the mechanical behavior of the moat excavation process and the impact of seasonal water level changes on the stability of the deep excavation. The article proposes preventive protection measures for archaeological excavations and discusses the application and development of conservation measures for such sites.

The Fenghuangzui Site is situated in the middle reaches of the Han River, on the southern edge of the Nanyang Basin, and administratively belongs to Xiangzhou District, Xiangyang City, Hubei Province, China, specifically within the jurisdictions of Qianwang and Yanying villages, Longwang Town. The site’s environment is characterized by distinct seasons, concentrated rainfall, and high average annual humidity exceeding 73%, making it a typical humid environment archaeological site. Figure 1 shows the archaeological excavation area and water system distribution of the Fenghuangzui site (cited from reference16).

The current archaeological excavation status and lake and river distribution of the Fenghuangzui site (adapted from ref. 16).

Currently, only partial sections of the south and west moats at the Fenghuangzui Site have undergone archaeological excavation. The excavated section of the west moat has been backfilled for protection purposes. The south moat excavation section is rich in historical information, with cultural layers spanning the Ming-Qing period, Tang-Song period, Han-Wei period, Meishan culture, Shijiahe culture, and Qujialing culture. Plans are underway to preserve and display the site in its original state. The south moat excavation section measures approximately 36 m wide and 6 m deep, with a trench-like shape at the bottom, primarily consisting of silt deposits near the base (Fig. 2).

The archaeological excavation section of the south moat is experiencing several conservation issues, primarily including: groundwater infiltration (Fig. 3), localized collapse of the pit walls (Fig. 4), localized subsidence of the ground surface (Fig. 5), deterioration of the site’s surface (Fig. 6), and structural cracks (Fig. 7).

The aforementioned conservation issues are closely related to the site’s environmental conditions. The Fenghuangtou Site is surrounded by a relatively developed water system, with the Xiaoqing River, Pazi River, and Fenghuang Creek flowing from north to south through the core area of the site. According to the 2021 geological drilling data, the groundwater level around the site ranges from 0.50 to 3.0 m below the surface, and the soil consists of Quaternary Holocene (Q4) fill and Pleistocene (Q3) fluvial and lacustrine clay.

Methods

The trial excavation section of the south moat at the Fenghuangzui Site has a longitudinal length of 36 meters, with a trapezoidal cross-section. The top width is 5.5 meters, the bottom width is 3.5 meters, and the depth is 6.0 meters, with a sidewall slope ratio of 1:6 (Fig. 8).

During the excavation of the moat, steep sidewalls formed on the sides and ends. As the excavation depth increased, the deformation and stress characteristics of the sidewalls exhibited similarities to the stability problems of soil slopes. To simulate the archaeological excavation process, the excavation depth was set at 1.5 m for each stage, as indicated by the dashed lines in Fig. 8, representing the incremental excavation depths.

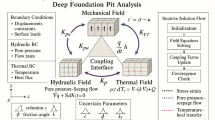

Mechanical analysis model

(1) Numerical model

In order to examine the mechanical behavior of the soil slope on the sidewall during excavation, this study utilized two numerical models from the realm of continuous medium solid mechanics: a three-dimensional stress model and a plane strain model (Fig. 9). The mathematical formulation for the three-dimensional stress analysis is given by Eq. (1), whereas the mathematical formulation for the plane strain analysis is presented in Eq. (2).

(2) Finite element model

Considering the impact of boundary conditions on the stress distribution around the moat, the numerical analysis model was selected with the following criteria: the distance from the bottom of the model to the bottom of the moat is not less than three times the excavation depth, the length of the extension segments at both ends of the moat in the longitudinal direction is not less than three times the burial depth of the site, and the width of the model is not less than eight times the maximum excavation width of the moat. Figure 9 shows the spatial geometric model, where the layered lines represent the positions of different soil layers.

The numerical analysis model was constrained by setting the boundary conditions as follows: the horizontal displacement of the model’s sides was fixed, and the translation of the model’s bottom was restricted. The resulting finite element model of the moat is shown in Fig. 10, which was discretized using 20-node hexahedral elements with uniform parameters.

(3) Geotechnical properties

Based on the geological survey data, the physical-mechanical properties of the soil in the excavated moat area arelisted in Table 1.

Mechanical behavior analysis of the excavation process

In order to investigate the mechanical behavior of soil deformation and instability during excavation, four scenarios with different excavation depths (1.5 m, 3.0 m, 4.5 m, and 6.0 m) were considered. The changes in horizontal displacement of the sidewall and the distribution of shear stress in the soil mass during excavation were examined and discussed.

(1) Analysis of pit deformation during the excavation process.

Figure 11 shows the contour map of horizontal displacement distribution during the excavation process. Figure 11a illustrates the overall distribution pattern of horizontal displacement of the soil around the moat. Figure 11b reveals the distribution pattern of horizontal displacement along the central cross-section. During the excavation, the removal of soil from the moat results in an unloading effect on the surrounding soil. As shown in Fig. 3, the excavation of the moat causes a significant horizontal displacement of the pit wall, with the maximum value located at the top of the sidewall (near the ground surface). Figure 11b shows the distribution pattern of horizontal displacement along each soil layer in the central cross-section of the moat. It can be seen that due to the unloading effect caused by excavation and the pressure exerted by the pit wall, significant horizontal displacement occurs not only in the soil layers above the pit bottom but also below it.

Figure 12 illustrates the correlation between the moat’s excavation depth and the horizontal displacement of the pit wall. The x-axis represents displacement values (with positive values denoting outward movement), while the y-axis represents excavation depths. At excavation depths of 1.5 m and 3.0 m, the pit wall displays an inward leaning behavior (deforming towards the soil), with maximum horizontal displacements of −12 mm and −20 mm, respectively. This suggests that the unloading effect induced by excavation alters the soil’s stress distribution while also decreasing the passive earth pressure on the sidewall’s exposed surface, leading to a deformation where the sidewall inclines towards the soil.

With the increase in excavation depth, when the depths reach 4.5 m and 6.0 m, the sidewall displays a trend of leaning outward near the bottom of the pit and inward at the top, with the outward leaning trend becoming more significant. At an excavation depth of 4.5 m, the maximum outward displacement is 4 mm, while the maximum inward displacement is 32 mm; at an excavation depth of 6.0 m, the maximum outward displacement increases to 22 mm, and the maximum inward displacement decreases to 28 mm. This law reveals that when the excavation depth exceeds 3.0 m, outward displacement occurs at the bottom of the pit, which increases substantially as the excavation depth increases. Moreover, when the excavation depth exceeds 4.5 m, the increase in outward displacement is accompanied by a decrease in inward displacement. The mechanism behind this phenomenon is attributed to the redistribution of soil stress caused by the increasing excavation depth. As the excavation depth surpasses 3.0 m, the increasing outward displacement also leads to an increased risk of instability of the steep soil slope near the pit wall, with the risk escalating as the excavation depth increases.

Analysis of soil cracking in the excavation pit during the excavation process

The strength and stability of the excavation pit were evaluated using shear stress as the criterion. Due to the low tensile strength of the clay, a tension-based failure criterion was used to predict soil cracking and local collapse.

As illustrated in Fig. 13, the first principal stress distribution in the moat pit wall induced by excavation is presented as a contour map. The maximum tensile stress, influenced by stress concentration, is located at the corner ends, and a distinct region of tensile stress distribution is evident along the upper surface of the pit wall on both sides. Figure 14 depicts the tensile stress concentration effect at the corner end of the moat, where the bottom of the pit exhibits the most notable tensile stress due to unloading resulting from excavation, which is a contributing factor to the outward deformation and cracking of the pit bottom.

Figure 15 illustrates the shear stress distribution on the mid-moat horizontal cross-section for excavation depths of 1.5 m, 3.0 m, 4.5 m, and 6.0 m. High-stress zones are highlighted in red and dark blue, with a threshold of 20 kPa. The peak shear stresses for these depths are 35 kPa, 84 kPa, 97.7 kPa, and 99.3 kPa, respectively, all occurring at the intersection of the excavation bottom and sidewall due to stress concentration caused by the corner geometry. As the excavation depth increases, the high-stress region expands from the corner of the excavation bottom into the foundation bearing layer and sidewalls, with a notable enlargement of the high-stress area.

Figure 12 shows that during excavation, the horizontal displacement of the sidewall is mainly attributed to the unloading effect caused by excavation when the depth is less than 3.0 m, resulting in reduced passive earth pressure on the sidewall soil and displacement towards the sidewall. As the excavation depth increases, the high-stress zone at the corner of the excavation bottom expands rapidly, leading to substantial increases in deformation of the soil in this area. The horizontal displacement of the sidewall is influenced by the deformation of the excavation bottom’s corner into the foundation bearing layer and sidewall, causing the sidewall to lean outward more pronouncedly.

Consequently, the variation in horizontal displacement of the sidewall, when the excavation depth is less than 3.0 m, is primarily attributed to the change in lateral earth pressure, which induces soil deformation, or local cracking and collapse. At relatively shallow excavation depths, the alteration in stress distribution within the soil is not pronounced, being confined to localized stress concentrations. The application of horizontal supports (as illustrated in Figs. 2–4) can offset the loss of lateral earth pressure. Nevertheless, when the excavation depth is larger (i.e., exceeding 3.0 m), the soil’s stress distribution undergoes significant changes, with a substantially high-stress area emerging at the corner of the excavation bottom. To mitigate the risk of instability, it is essential to augment the soil’s rigidity, load-bearing capacity, and overall cohesion.

Results

The Fenghuangzui archaeological site is located in the Jianghan Plain, where the river network is dense and there are many lakes. The area is prone to flooding in early summer and experiences dryness in autumn and winter. The seasonal changes in water level lead to variations in the mechanical properties of the soil and the effective stress, which is one of the internal factors that can trigger instability in the moat. For example, the Liangzhu archaeological site and the Nanjing Baoning Temple underground palace17,18,19 have all experienced changes in the mechanical properties of the soil due to groundwater activity, resulting in changes in the effective stress within the soil, ultimately leading to local collapses, cracks, or overall instability, which poses a threat to the safety of the site itself and the people involved.

On-site engineering geological drilling (up to a maximum depth of 14.0 m) and laboratory geotechnical tests were conducted to determine the rock and soil mechanics parameters for the moat area, which are presented in Table 1. To simplify the calculations, the clay is treated as a single engineering geological unit. As water level fluctuations are the primary factor influencing changes in the physical and mechanical properties of the soil, the calculation parameters are based on the physical and mechanical properties of the clay soil in its drained (FBH) and saturated (BH) states. The resulting material calculation parameters are summarized in Table 2.

Analysis of soil deformation due to water level fluctuations

Based on on-site monitoring data from January 2024 to January 2025, the excavated section of the moat has a bottom elevation of −6.000. During the summer rainy season, the water level reaches an elevation of −3.200 (with the existing ground surface at ±0.000), causing the water to accumulate above the bottom of the moat. In the autumn and winter seasons, the water level generally stabilizes around −6.000, leaving the moat dry.

A series of simulations was conducted to evaluate the influence of groundwater level fluctuations on the surrounding soil. The simulations focused on the relationships between groundwater level and surface settlement and groundwater level and horizontal deformation of the moat’s sidewall at specified elevations of −3.200, −4.800, and −6.000.

(1) Analysis of the influence of water level changes on ground movement and settlement

Numerical simulations yielded the relationship curve between ground settlement and horizontal distance from the moat wall as a function of water level fluctuations, as depicted in Fig. 16. The surface subsidence profile displays a parabolic decay pattern with respect to the horizontal distance from the moat boundary, characterized by a decreasing rate of decay. A critical distance of 2.5 times the moat width is identified, beyond which the surface subsidence becomes negligible. The amount of surface subsidence increases with rising groundwater levels, and the decay curve is influenced by the water level, with higher levels leading to more rapid attenuation. This pattern reveals the spatial distribution of surface subsidence around the moat, with maximum values occurring at the edge and decreasing parabolically with distance. The mechanism driving this change in surface subsidence is the formation of a relative “weak layer” due to water level fluctuations, which affects the internal stress distribution within the soil.

(2) Interaction between groundwater level variations and horizontal deformation of the moat wall

Water level fluctuations trigger horizontal displacements in the soil slope formed by the moat, offering a more direct insight into potential instability risks. The depth-wise distribution curve of horizontal displacement is presented in Fig. 16, where positive values signify displacements towards the surface. The maximum horizontal displacement occurs at a position approximately 1/4 of the height from the bottom of the moat, and as the water level increases, the horizontal displacement also increases, but the rate of increase of the maximum displacement exhibits a more marked trend(as illustrated in Fig. 17).

Study on the stability failure mechanism of deep foundation pits (moats)

The plastic strain cloud maps of the moat deep excavation at critical instability were simulated using the finite element strength reduction method, with water levels at elevations of −3.200, −4.800, and −6.000, respectively (the strain threshold for critical instability was set to 0.02), as shown in Figs. 18–20.

The changes in the horizontal displacement of the moat wall and the settlement of the moat floor caused by water level fluctuations comprehensively reflect the impact of water level changes on the deformation of the surrounding soil of the moat, while the analysis of the critical unstable state of the soil slope on the side of the moat caused by water level fluctuations reveals the mechanical mechanism of soil slope instability due to water level changes20,21.

As shown in Figs. 18–19, when the water level is above the bottom of the moat, the saturated soil layer below the water level has a lower shear strength than the soil layer above the water level, forming a relatively weak soil layer. Consequently, the plastic zone formed in the stress concentration area at the corner of the moat bottom gradually extends into the saturated soil layer. As the plastic zone expands, a potential slip surface forms and eventually causes local instability of the slope. The red areas in Figs. 18–19 indicate the formation of a plastic slip surface at the critical state of local instability, which is located in the plastic zone of the saturated soil layer, causing the soil above the water level to lose support and ultimately resulting in local instability.

As shown in Fig. 20, when the water level is at or below the bottom of the moat, the plastic zone first forms in the foundation soil layer beneath the moat floor and penetrates through it, creating a plastic slip surface in the foundation layer. The slope of the pit wall, due to local failure of the foundation, experiences weakened support on the exposed face, leading to a rapid increase in shear stress in the soil. As a result, the plastic zone extends from the bottom corner upwards, forming a penetrating shape and ultimately resulting in overall instability. The red area in Fig. 19 indicates the critical state of overall instability, where the plastic zone extends from the corner of the moat floor to the foundation soil layer, causing deformation and weakening of the foundation soil layer, which in turn weakens the slope support, eventually forming a plastic slip surface that penetrates both the foundation and the slope, leading to overall instability.

Therefore, based on the water level being above or below the elevation of the moat floor, the types of slope instability can be categorized into local instability and overall instability. The mechanisms and preventive protection targets for these two types of instability also differ. When the water level is above the moat floor, the risk of local slope instability significantly increases, and controlling the development of plastic zones below the water level to form slip surfaces is the primary objective of preventive protection. In contrast, when the water level is below the moat floor, the main goal of protection is to increase the bearing capacity and stiffness of the foundation soil layer, control plastic deformation and the formation of slip surfaces in the foundation layer, and prevent overall slope instability.

Discussion

Unlike the dry region cultural heritage sites where weathering, cracking, erosion, and external forces are the main external factors triggering structural safety issues, the preventive protection research on the moat excavation of the Fenghuangzui site, located in the core area of the Jianghan Plain, represents the characteristics of preventive protection for earthen cultural heritage sites in China’s humid regions. The Fenghuangzui site is massive, with a complex geological and hydrological environment. The overlying soil layer consists of fill soil, clay, and silty clay, while the cultural layer below is primarily composed of silty clay, which is affected by seasonal groundwater level fluctuations. Among these, the excavation of the moat site is the most representative. Studying the mechanical behavior of the soil during excavation and the instability mechanism of the steep slope formed during excavation can not only predict potential safety risks but also provide a basis for preventive protection22,23,24. The conclusions of this study can serve as a valuable reference for the excavation and conservation of similar archaeological sites.

This paper takes the southeast segment of the Fenghuangji ruins’ moat as its research subject. Based on archaeological, surveying, and measurement data, it analyzes and discusses the mechanical behavior of the moat during excavation and its impact on the site itself and its surroundings. Additionally, it examines the effects of seasonal water level changes on the stability of the moat remains during the later stages of exhibition and opening to the public, providing relevant conclusions and recommendations.

(1) The unloading effect induced by excavation triggers a stress redistribution in the adjacent soil mass. For excavation depths greater than 3.0 m, the lateral displacement of the moat’s steep side slope increases substantially, with the maximum displacement occurring at the base of the excavation. As the excavation depth increases, the rate of increase in lateral displacement grows, elevating the risk of slope failure.

(2) When the groundwater level is higher than the bottom of the moat, the land subsidence value decreases in a parabolic shape as the distance from the moat edge increases, with the rate of decrease slowing down gradually. As the water level rises, the land subsidence increases accordingly, and the higher the water level, the faster the rate of decrease in land subsidence.

(3) With the rise in groundwater level, the lateral displacement of the moat’s sidewall undergoes accelerated growth, reaching its maximum value at a point roughly one-quarter of the way up from the base of the moat, measured as a fraction of the total moat depth.

(4) When the water level is below the bottom of the moat, the bearing capacity and stiffness of the foundation soil at the base of the moat are reduced due to the influence of groundwater. A plastic slip surface gradually forms, weakening the supporting conditions of the slope. As this plastic slip surface extends from the base to the slope, it leads to overall instability.

(5) When the water level is above the bottom of the moat, a plastic region forms and extends in the saturated soil layer below the water table on the slope, eventually creating a penetrating shear failure surface that leads to local instability of the slope.

(6) The localized unloading effect caused by increasing excavation depth, which in turn affects the stress distribution around the excavated soil, is the direct cause of deformation and cracking on the moat’s surface, channel bottom, and sidewalls. Pre-excitation protective measures should aim to compensate for this unloading effect. For example, using anti-sliding piles or pile-anchor systems on both sides of the excavation site can significantly improve structural safety.

(7) The saturated soil layer formed by water level changes has a weakened shear strength, making it prone to plastic shear failure. When the water level is above the slope’s base, a cable anchor system can effectively enhance the slope’s overall stability and reduce the risk of local instability. When the groundwater level is critical but not exceeding the slope’s base, a pile-anchor system or anti-sliding piles can alter the load transfer path of the foundation soil, which deserves attention.

(8) The best months for archaeological excavations at the Fenghuangzui site are from August to November every year. Due to the high water-holding capacity of clay and silt, which increases the risk of sliding when the strength of the soil decreases after encountering water, it’s necessary to do a good job of drainage and precipitation. Additionally, to reduce the impact of water on the walls of the moat, waterproof membranes can be used, which can prevent water from seeping into the surface in contact with the soil and control the soil’s humidity levels. If allowed by the archaeological excavation, a slope can be created to reduce the risk of instability of the pit wall.

Data availability

The authors declared that all data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Code availability

The code that supports the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Wang, Y., Guo, J. & Zhang, W. Experimental research on the performance of a novel geo-flament anchor for an Earthen architectural site. Herit. Sci. 2, 1–15 (2023).

Wang, Y., Dong, Z., Wei, L. & Lei, F. Experimental research on destruction mode and anchoring performance of carbon fiber Phyllostachys pubescens anchor rod with different forms. Adv. Civ. Eng. 03, 1–13 (2018).

Lu, W. et al. Experimental study on bond-slip behavior of bamboo bolt-modified slurry interface under pull-out load. Adv. Civ. Eng. 01, 1–23 (2018).

Chonggen, P. & Keyu, C. Research progress on in-situ protection status and technology of earthen sites in moisty environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 253, 119219 (2020).

Nogueira, R., Ferreira, P. & Augusto, G. Artificial ageing by salt crystallization: test protocol and salt distribution patterns in lime-based rendering mortars. J. Cult. Herit. 45, 180–192.20 (2020).

Pei, Q. Q., Wang, X. D., Zhao, L. Y., Zhang, B. O. & Guo, Q. L. A sticky rice paste preparation method for reinforcing earthen heritage sites. J. Cult. Herit. 44, 98–109 (2020).

Wang, N. & Zhang, J. Evaluation on the Long-term Stability of the Simulated Archaeological Tests of Pre-Historic Earthen Sites in Humid Environments. 158–140 (in Chinese) (Dunhuang Research, 2018).

Chen, P. & Zhang, J. Application of FLAC3D in Pre-judging the Stability of Vertical Excavation Units of Prehistoric Archaeological Sites in Moist Environments. 124–130 (in Chinese) (Dunhuang Research, 2016).

Xudong, W. Numerical simulation of the behaviors of test square for prehistoric earthen sites during archaeological excavation. J. Rock. Mech. Geotech. Eng. 10, 567.e578 (2018).

Banne, S., hailendra P. & Dhawale, A. runW Slope stability analysis of xanthan gum biopolymer treated laterite soil using PLAXIS limit equilibrium method (PLAXIS LE). KSCE J. Civil Eng. 28, 1205–1216 (2024).

Sari, P. T. K., Mochtar, I. B. & Lastiasih, Y. Special case on landslide in Balikpapan, Indonesia viewed from crack soil approach. KSCE J. Civil Eng 28, 2173–2188 (2024).

Sherong, Z. & He, J. Deep-learning-based landslide early warning method for loose deposits slope coupled with groundwater and rainfall monitoring. Comput. Geotech. 165, 105924 (2024).

Kaihang, H. A methodology for evaluating the safety resilience of the existing tunnels induced by foundation pit excavation. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 158, 106362 (2025).

Deyang, C. Study on the coupling effect and construction deformation control of large deep foundation pit groups involving iron considering the coupling effect of seepage stress. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 54, 102780 (2024).

Nowroozi, V., Hashemolhosseini, H., Afrazi, M. & Kasehchi, E. Optimum design for soil nailing to stabilize retaining walls using FLAC3D. J. Adv. Eng. Comput. 5, 108–124 (2021).

Xinyue, A., Jianfang, W. & Tao, L. Chemical insights into pottery production and use at Neolithic Fenghuangzui earthen-walled town in China. npj Herit. Sci. 6, 11 (2025).

Lercari, N. Monitoring earthen archaeological heritage using multi-temporal terrestrial laser scanning and surface change detection. J. Cult. Herit. 39, 152–165 (2019).

Fujii, Y., Fodde, E. & Watanabe, K. Digital photogrammetry for the documentation of structural damage in earthen archaeological sites: the case of Ajina Tepa, Tajikistan. Eng. Geol. 105, 124–133 (2009).

Nouri, H., Fakher, A. & Jones, C. J. F. P. Evaluating the effects of the magnitude and amplification of pseudo-static acceleration on reinforced soil slopes and walls using the limit equilibrium horizontal slices method. Geotext. Geomembr. 26, 263–278 (2008).

Liu, Y. Stability analysis of an expansive soil slope under heavy rainfall conditions with different anchor reinforcements. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84799-x (2025).

Jian, X., Zha, X. D., Zhang, H. R. & Yang, J. M. Research on the damaging mechanisms of expansive soil in subgrade. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. https://doi.org/10.1080/15376494.2022.2156004 (2022).

Rong, Z. & Bin, W. Analysis of the effects of vertical joints on the stability of loess slope. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-31033-9 (2023).

Xuancheng, R. & Weifeng, S. Influence of tension cracks on moisture infiltration in loess slopes under high-intensity rainfall conditions. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88865-w (2025).

Ranke, F. & Longsheng, D. Research on response characteristics of loess slope and disaster mechanism caused by structural plane extension under excavation. Sci. Rep. 14, 28700 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2020M683672XB), Independent Research and Development project of State Key Laboratory of Green Building in Western China (LSZZ202217). The authors would also like to express our special thanks to the reviewers for their constructive suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhang Weixi contributed to designing the research study, developing the methodology, overseeing the data collection process, and overall revision the manuscript. Wang Yulan originated the research concept, designed the project plan, obtained funding for the study, and prepared the manuscript. Wang Ji has performed a careful check of the manuscript’s grammar and formatting. Li Changying was responsible for assessing the value of the site and analyzing its current condition. Lei Fan handled the preparation of figures and tables, as well as the layout of the paper. Yuan Feiyong was responsible for collecting, sorting, and editing historical documents and records. Tian Hui was responsible for on-site research and gathering photographic documentation of damage or deterioration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Weixi, Z., Yulan, W., Ji, W. et al. Investigation on the mechanism of deep trenching damage in humid archaeological excavation zones. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 398 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01948-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01948-9