Abstract

The ecological security pattern (ESP) is crucial for biodiversity, environmental quality, and regional sustainable development. This study comprehensively analyzed karst desertification control (KDC) forests. Using a comprehensive approach, we analyzed KDC forests through normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), land use/land cover (LULC), and other data. Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis (MSPA) was applied to identify ecological sources (ES), while circuit theory extracted ecological corridors (EC) and nodes (EN) to build a hierarchical ESP. The results show: (1) Severe fragmentation of KDC forest patches, with area significantly decreasing as karst desertification (KD) severity increases. (2) Insufficient connectivity and high resistance to ecological flow causing internal degradation. (3) The SLX, HFH, and HJ each extracted 108, 68, and 113 EC, and 67, 20, and 40 EN. (4) The ESP of forests with varying levels of KDC exhibited significant differences. Findings advance KDC forest structure-function insights, providing a scientific foundation for targeted restoration strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ecological security constitutes an essential component of national security, providing the foundation for other forms of security, including national defence, political, and economic security1,2. Global climate change and rapid socio-economic development have led to dramatic changes in land use patterns, intensifying the conflict between humans and natural ecosystems3,4. hese changes have triggered issues such as land degradation and biodiversity loss, disrupted ecosystem structures, weakened the connectivity of ecological security patterns, and posed significant threats to regional sustainable development5,6. The necessity for ecological security, as a fundamental requirement for the utilisation of regional resources and a crucial element in the attainment of the United Nations’ sustainable development objectives, has emerged as a pressing social imperative. Currently, China has elevated the construction of a land ESP comprising “two screens and three belts” and a marine ESP comprising “one belt, one chain and several points” to a national strategic level7. The construction of an ESP can effectively mitigate the conflict between economic development and ecological protection, maintain the stability of biodiversity and promote sustainable development in the region by providing a feasible implementation path8,9.

The ESP is an integrated spatial decision-making framework for ecological protection and restoration, incorporating key spatial elements such as ecological redlines and restoration zones10,11. This line of research originated in landscape ecology and has since evolved to exhibit a trend toward diversification and integrative development in both research themes and paradigms12. American scholars studying ESP place special emphasis on the in-depth exploration of modeling ecosystem processes, conservation, and security policies for ecological reserves13. In contrast, Professor Yu Kongjian in China systematically proposed a set of theories on ESP and its methodology focused on habitat patches, ecological corridors (EC), and buffer zones, with the aim of offering robust theoretical support and practical guidance for biological conservation14. Subsequently, the research paradigm of “ecological sources (ES) identification - constructing of ecological resistance surface (ERS) - EC and ecological nodes (EN) extraction” has evolved into a fundamental and core research approach for ESP development9,15, establishing a strong theoretical foundation and research framework for ecological environmental protection and restoration. In this research area, scholars have thoroughly explored the construction and optimization of ESP for various spatial scales such as cities16,17, provinces18, watersheds19, and ecologically fragile areas10. The research was primarily based on multiple perspectives, including enhancing ecosystem structure and function20, optimizing land use patterns21, and considering social equity needs22. They employed a variety of methods, such as ecological sensitivity assessment23, ecological risk assessment24, ecosystem service assessment25, morphological spatial pattern analysis model (MSPA)26, minimum cumulative resistance model (MCR)24, and circuit theory27. Overall, the integration of the MSPA and MCR models effectively captures the impact of landscape pattern changes on ecological processes, identifies potential corridors and nodes, and thereby enhances the objectivity and reliability of ecological assessments. Meanwhile, the MCR model has also been widely applied in territorial spatial planning and the delineation of ecological redlines28,29.

Current ESP research has made progress in determining key parameters using various methods, each with advantages, limitations, and specific applications30. However, pressing issues and challenges remain. First, the methods for identifying ecological sources are inadequate, as they fail to fully consider ecological processes, historical land use changes, and the coupling between ecological supply and social demand. Second, corridor identification focuses mainly on the location of linear elements, with insufficient consideration of corridor width. Although the MCR model determines direction and location, it overlooks the random movement behavior of species. Circuit theory is emerging as a promising approach for future corridor modeling. Third, the current framework rarely integrates China’s specific ecological needs and national context. It is necessary to explore a comprehensive framework incorporating “source–resistance surface–corridor–node–network space.” In addition, although the theoretical and methodological systems in this field are relatively mature, most research has focused on terrestrial ecological security patterns31. There has been insufficient attention to outflow-type watersheds and ecologically vulnerable areas. Future studies should prioritize the construction of ecological security patterns in such regions, such as the karst areas in southern China.

Classical land use change research primarily focuses on identifying socioeconomic driving forces, often using the CLUE model to establish relationships between indicators through econometric methods and assess land use changes under different scenarios32. Subsequently, dynamic process modeling emerged, integrating remote sensing data with models to simulate land use changes33. In current cutting-edge research, the MCR model extends the quantification of land use change impacts to the ecological security dimension34. Contemporary land auditing techniques have shifted toward ecological performance assessment, using remote sensing to verify the implementation of ecological management measures. Forest resource auditing relies on satellite data such as Landsat to dynamically monitor changes in land use patterns35. Current land use change research shows notable deficiencies in constructing forest ESP. Therefore, coupling the MSPA and MCR models—by quantifying key ecological nodes and simulating optimal path networks—can effectively bridge the gap between pattern characterization and process simulation in integrated studies.

KD poses a significant threat to ecological security and economic development in China’s karst regions, and its landscape differs markedly from that of existing World Natural Heritage sites. The region is characterized by unique biological and cultural landscapes. With effective restoration and conservation, some areas have the potential to be designated as new karst World Heritage sites.36. Particularly in South China Karst, KD is a grave issue. South China Karst faces severe KD, experiencing significant ecosystem degradation and the added pressure of lagging behind in economic development. This situation presents a serious challenge to the region’s sustainable development37,38. Given the unique surface-subsurface binary three-dimensional spatial structure characteristics of karst landforms, the ecological environment of this region presents significant particularity and vulnerability39. In dealing with the problem of KD, the forest restoration-led governance strategy is particularly important40. This not only plays a key role in guaranteeing the sustainable development of the ecological environment of the entire karst areas but also is of vital significance in constructing an ecological barrier in the upper reaches of the Yangtze River and the Pearl River, ensuring the overall ecological security under the strategy of China’s western development41,42.

Forest ecological security is essential to achieving multiple environmental and developmental goals outlined in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This study aims to understand and assess the protection, restoration, and sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, including sustainable forest management, combating KD, reversing land degradation, and halting biodiversity loss. Based on the construction of an ecological security pattern, the study precisely identifies key areas for KD restoration, formulates sound strategies for sustainable forest management, prevents overexploitation, and safeguards habitat security. Currently, the primary challenge facing China’s forest ecological security is the imbalance and instability of regional development, particularly evident in the western region43. Furthermore, existing research lacks the establishment of ESP centered around forests. In light of this, this study focuses on the forest ecosystem in the KDC, aiming to develop the necessary ESP44. The objective is to promote a harmonious symbiosis between ecological preservation and human development needs, effectively addressing potential conflicts between the two. The specific objectives are: (1) The MSPA and landscape connectivity index were used as analysis tools to scientifically and accurately identify and establish ES. (2) Two major categories of natural and human factors were analyzed, and an ERS was constructed. (3) Based on circuit theory, the flow patterns of ecological flows in the landscape were analyzed in depth, and key EC and EN were extracted accordingly. (4) A comprehensive and systematic ESP of forests was constructed by integrating the ES, ERS, EC and EN mentioned above. Based on this, we propose targeted ecological restoration and optimization strategies. This study not only provides new perspectives for understanding ESP in ecologically fragile areas but also offers practical guidance for their ecological restoration and optimization.

Methods

Study area

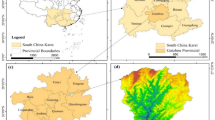

Three study areas with overall structure and feature of KDC were selected in South China Karst (Fig. 1). Salaxi Highland Mountain Potential-Mild Karst Desertification Comprehensive Prevention and Control Research Area (SLX) (27 °11′09″ N-27 °17′28″ N, 105 °01′11″ E-105 °08′38″ E). With a total area of 86.27 km2. The karst area covers 74.25% of the total area, with altitudes ranging from 1511 to 2186 meters. The region has an average annual temperature of 12.8 °C and an annual precipitation of 984 mm. Due to early human-land conflicts, the primary vegetation was essentially destroyed, and now the area is dominated by secondary vegetation like Pinus armandi and Juglans regia, with a low density of forest stands. Hongfenghu Highland Basin Mild-Moderate Karst Desertification Comprehensive Prevention and Control Research Area (HFH) (26 °27′55″ N-26 °34′46″ N, 106 °18′16″ E-106 °23′16″ E). The study area covers a total area of 60.41 km2. karst area accounts for 95.1% of the total area, with an average elevation of 1300 m, an average annual temperature of 14.1 °C, and an average annual precipitation of 1180.9 mm. The area is a harsh environment for plant growth due to the widespread presence of carbonates. Most of the primary vegetation has been destroyed and is now dominated by secondary forests and scrub, such as Prunus persica, Prunus salicina, and Cupresus duclouxiana. The area has a mono-structured vegetation with a high stand density. Huajiang Highland Valley Moderate-Intensity Karst Desertification Comprehensive Prevention and Control Research Area (HJ) (25 °37′07″ N-25 °42′25″ N, 105 °35′11″ E-105 °43′18″ E). The total area of the study area is 51.62 km², with 87.92% being karst area. The elevation ranges from 443 to 1358 meters, with a mean annual temperature of 18.4 °C and annual precipitation of 1100 mm. The area has an extremely fragile ecological environment, typical of the ecological environment of karstic dry-heat river valleys. The surface is extremely arid, with thin and discontinuous soils and low vegetation cover. The primary forest vegetation communities consist of mixed evergreen deciduous broad-leaved forests, including Zanthoxylum planispinum and Broussonetia papyrifera. These forests have a distinctly secondary nature due to anthropogenic disturbances in areas like hilltops and steep slopes.

Data source

This study utilized multivariate data including normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), land use/ land cover (LULC), Digital Elevation Model (DEM), slope, and road network, all collected specifically for the year 2020. NDVI and LULC are annual average values. To maintain data quality and spatial reference consistency, all data were standardized to the GCS_WGS_1984 coordinate system, and raster data were resampled to a consistent resolution of 30 meters. Detailed sources of all data are provided in Table 1. The raster data and their corresponding resolutions we selected effectively capture key landscape pattern details at the regional scale, such as farmland patches, small forest areas, and boundaries of built-up land, making them commonly used and recommended data sources for watershed-scale ESP analysis.

Methods and steps

The methods and steps for establishing an ecological security pattern for KDC forests (Fig. 2) comprise four principal elements, each of which is elucidated in turn in the following sections.

Identifying ES

MSPA, as proposed by Vogt et al. in 2007, is a cutting-edge method rooted in mathematical morphology principles, designed to efficiently classify landscape types in binary raster images. This method not only rapidly identifies various landscapes but also offers a wide scope of application in ecology, as it is not restricted by study scale45. In our research, we selected arable land, grassland, water bodies, and construction land as background landscapes, while woodland and shrubland were designated as foregrounds based on the study area’s characteristics. Utilizing Guidos Toolbox software, we conducted MSPA analysis on LULC raster data from three study areas, employing the default eight-neighbourhood analysis. This analysis successfully identified seven core landscape ecotypes across the study areas: core, islet, loop, bridge, perforation, edge, and branch. The ecological significance of these landscape types is outlined in Supplementary Table 1. The core landscape type is deemed the ‘source’ of ecological processes due to its high ecological suitability46. Subsequently, we utilized Conefor 2.6 software to analyze the landscape connectivity of core areas identified through MSPA. By calculating landscape probable connectivity (PC) of patches and the importance of patch connectivity (dPC), we quantitatively assessed the connectivity and significance of each patch in the ecosystem. Larger PC values indicate greater patch connectivity, while larger dPC values suggest a more crucial role in maintaining ecosystem connectivity. The formulae are presented in Eqs. (1), (2) and (3).

Where: IIC is the overall connectivity value of all ecological patches in the study area, with values ranging from 0 to 1; n is the total number of ecological patches in the study area; ai and aj are the areas of ecological patch i and ecological patch j; p* ij is the maximum value of the possibility of a particular species migrating directly between the two major ecological patches i and j; pc’ is the value of landscape connectivity after removing the ecological patches from the study area.

Establishing ERS

The variability between different landscape units significantly impacts species migration, with hindrance levels negatively correlated with ecosystem service smoothness47. The resistance factor index system plays a crucial role in assessing regional ecological security. For instance, changes in DEM directly affect land resource utilization patterns and distribution, while alterations in LULC have a profound impact on material and energy flow as well as information exchange within and between ecosystem services. For example, DEM directly influences the spatial utilization and distribution of land resources48; LULC affects the exchange of matter, energy, and information within and between ecological source areas49; DR increases ecological disturbance from traffic, including noise pollution, light pollution, and habitat fragmentation, resulting in higher resistance values50; slope limits ecosystem connectivity and species migration51; and high NDVI values generally indicate greater vegetation productivity, with well-vegetated areas providing more continuous habitats and migration corridors for species52. In consideration of the natural characteristics of the study area, including topography, geomorphology, climate, and relevant social factors, we identified five key evaluation indicators for constructing the ERS: LULC, NDVI, DEM, slope, and distance from the main road (DR). Utilizing the natural breakpoint method in ArcGIS software, each resistance factor was categorized into five levels. Through hierarchical analysis, we determined the weight of each resistance factor, as detailed in Supplementary Table 2. Subsequently, by employing the spatial superposition analysis function in ArcGIS, we calculated the integrated ERS resistance value for ecological land by weighting and summing the factors. The resistance score ranges from 1 to 9, with higher values indicating greater resistance. Specific details regarding resistance grading and value assignment can be found in Table 2.

Extracting EC

EC plays a vital role in facilitating the efficient exchange of matter and energy among ES, ultimately contributing to the overall functionality of regional ecosystems53. Drawing inspiration from circuit theory, we equate ecological resistance to electrical resistance in a circuit, viewing ecological flow as a randomly wandering electric current. This innovative approach allows for a more precise simulation of species movement in natural environments. In this study, we developed a comprehensive ERS and integrated a random wandering model within the framework of circuit connectivity. By utilizing current difference data from the Circuitscape program and the Linkage Mapper plug-in, we accurately identified the optimal EC by determining the coastal paths with the least cumulative resistance between ES within the study area.

Identifying EN

EN are crucial areas of high landscape connectivity within EC that, if damaged, could have severe consequences for the ecosystems in the region. Ecological barrier sites (EBS) are locations where species face obstacles in migrating and dispersing among ES patches. The restoration of EBS can enhance landscape integrity and connectivity54. This study utilized the Circuitscape program, which is based on circuit theory, to calculate current densities for precise identification of EN. The ‘all to one’ mode of the Pinchpoint Mapper module was employed to pinpoint EN, with a cost-weighted distance of 0.2 km set for the EC. The Barrier Mapper module in Circuitscape was utilized to identify EBS, with iterations set at 500, 400, and 500 m gradients.

Results

MSPA analysis

The results of the MSPA analysis presented in Table 3 indicate that the proportion of islet area to the total ecological landscapes area increased with higher KD class, while the opposite trend was observed for perforation. In the SLX, the total area of the 7 ecological landscape types was 3394.98 hm2. The core area was the largest, covering 1312.65 hm2, which represented 38.66% of the total ecological landscape area. edge, core, islet, branch, and bridge areas accounted for 30.05%, 0.96%, 4.96%, 11.79%, and 10.72% of the total ecological landscape area, respectively. The Loop area, at 2.86 hm2, was the smallest, comprising 2.86% of the total area, indicating limited flow and connectivity of ecological elements between the core and other landscape types. The total ecological landscape area in the HFH was 1237.05 hm2, and it was divided into core, edge, branch, islet, loop, and perforation with proportions of 38.79%, 35.35%, 11.56%, 6.56%, 4.77%, 2.50%, and 0.47% respectively. The proportions of bridge and loop were the smallest, suggesting poor connectivity and high resistance to ecological flow. In the HJ, the total ecological landscape area was 730.44 hm2, with proportions decreasing in the order of edge, core, bridge, islet, loop, and perforation at 29.60%, 20.93%, 19.95%, 17.05%, 8.74%, 3.63%, and 0.10% respectively. The edge area was larger than the core, indicating fragmentation and degradation within the core.

As shown in Fig. 3. The core distribution of the SLX is spread across its northern, central, and southern regions, showing a relatively balanced pattern. However, noticeable perforations in the southern and northern core areas indicate the intrusion of non-ecological landscapes or worsening ecosystem degradation. These perforation areas act as barriers to ecological elements’ flow, impacting the ecosystem’s natural circulation and balance. In contrast, the HFH core is mainly in its middle part, while the HJ core leans towards the north-west and south, with fewer perforations. Islets in these regions play a crucial role in enhancing ecosystem diversity by serving as temporary migration sites, reducing distances between habitats, and supporting ecological element flow. Islets in the SLX central part, HFH north-central part, and HJ southern part contribute significantly to material cycling, energy flow, and information transfer in the ecosystem.

ES extraction

Based on the results of MSPA core area identification and landscape connectivity analysis (Fig. 4), The selection of core area maps with dpc values greater than 1 and an area greater than 0.5 hm² was made as a general ecological source site. Similarly, maps with dpc values greater than 10 were selected as important ecological source sites, ability to provide optimal habitat conditions for biological survival, and significant role in maintaining landscape connectivity. Specifically, 45 forest patches covering 918.18 hm2 were extracted from SLX, representing 10.62% of the study area, with key ES identified as No.2, No.5, and No.38. Similarly, 32 forest patches totaling 350.73 hm2 were extracted from HFH, accounting for 5.80% of the study area, with important ES identified as No.19, No.24, and No.28. In the HJ, a total of 50 forest patches covering 118.62 hm2 (2.30% of the study area) were identified, with patches No. 8 and No. 9 being highlighted as important ES.

ERS analysis

In this study, we used the ArcGIS raster calculator to refine the reclassification and distance analysis of NDVI, slope, LULC, DEM and DR. After this series of processing, we successfully generated resistance surfaces for each single factor. These single-factor resistance surfaces were subsequently manipulated by superposition to form a ERS for each study area (Fig. 5). The distribution of the integrated resistance surface indicates that ecological circulation resistance values are notably concentrated in village areas with high land use intensity, particularly peaking along the roads. This pattern demonstrates a gradual decrease from the central region towards the periphery. The presence of large impervious surfaces in these concentrated areas is the main factor hindering crucial ecological processes like species migration and material cycling. In the SLX, ecological stress is relatively low due to significant population loss. Apart from the area along the southern highway, sporadic high values of ecological resistance were observed in the rest of the region, albeit significantly lower than in other study areas. On the contrary, the HFH presents a different scenario. This region is densely populated, possesses extensive arable land, and has a relatively low density of economic forestry, all of which contribute to the high overall ecological resistance values in the area. Lastly, the HJ displays distinct ecological characteristics owing to its unique geographical location and climatic conditions. Situated in the plateau valley area, the region experiences a notable microclimate characterized by dry and hot river valleys, large areas of low shrub economic forests, and sparse growth of secondary forests. These features result in higher ecological resistance values and increased ecological pressure in the region.

EC distribution analysis

In this study, the Linkage Mapper plug-in was utilized to asses the significance of EC by analyzing the results from the Centrality Mapper module. Duplicate EC were identified and removed to ensure accuracy. Level 1 EC primarily connect short-distance ES, Level 2 EC enhance longer-distance source connectivity, and Level 3 EC facilitate connectivity between key and general ES (Fig. 6). In the SLX, a total of 108 EC were identified, covering 109.34 km. Of these, 38 primary EC, totaling 29.50 km, were located in the central region and extended towards the west, north, and east. The 46 secondary EC, which formed the majority, primarily connected important ES in the north with general ES in the central area. Furthermore, 24 tertiary EC were mainly found in the southern part of the study area, serving as key connectors between central and southern ES. In the HFH, 68 EC with a total length of 59.44 km were identified. The 28 primary EC were concentrated in the central region, while secondary and tertiary EC were situated in the western and eastern parts of the study area, respectively. Lastly, in the HJ, a total of 113 EC spanning 128.10 km were identified. The primary and tertiary EC were predominantly located in the southern region, with 54 secondary EC serving as vital links between the northern and southern ES.

EN distribution analysis

EN play a crucial role in ecological processes, with the capacity to cause irreversible harm to the ecosystem through chain reactions due to their high vulnerability. utilizing the natural breakpoint method, we classified these pinchpoints into five levels of protection. The top three levels, EN I, EN II, and EN III, were meticulously ranked based on their descending significance. In the development of ESP, the ecological primary protection zone, as a concentrated area of EN, is a crucial area that requires special attention and significant protection. For the SLX, a total of 47 EN covering 22.05 hm² were identified, primarily located in the central and northern parts of the area (Fig. 7a). In the HFH, 10 ENs covering 4.14 hm² were identified, evenly spread across the central forest contiguous area (Fig. 7b). In the HJ, 28 ecological pinch points covering 24.57 hm² were identified, mainly clustered in the northwestern low-elevation area (Fig. 7c), with the largest pinch point area reaching 9.51 hm². Similarly, the current basin is classified into five categories using the natural breakpoint method, with the top three classes further divided into ecological first-improvement, second-improvement, and third-improvement zones in descending order. The Ecological Class I Improvement Area serves as an EBS, significantly hindering ES flow and is a key focus for planning and restoration within the ESP. A total of 20 ecological barrier points, covering 555.66 hm2, were identified in the SLX, primarily concentrated around buildings and roads (Fig. 7d). Additionally, 10 barrier points covering 420.12 hm2 and 12 barrier points covering 379.53 hm2 were identified in the HFH (Fig. 7e) and HJ (Fig. 7f), respectively, with barriers in these areas mainly located at higher elevations.

ESP construction

Our research highlights primary and secondary ecological reserves as crucial areas for ecological protection. We have also identified primary improvement zones as key sites for ecological restoration, aiming to enhance the ecological environment through systematic and targeted actions. Furthermore, we categorize the first-level EC as a key EC, the second-level EC as a significant EC, and the third-level EC as a strategic reserve area for future restoration endeavors, ensuring the scientific development of the ESP in KDC forest. The core framework of the SLX consists of ‘two horizontals, three verticals, five stones, and three areas’ (Fig. 8-SLX). In this layout, the ecological restoration area and the key conservation area hold significant importance, covering 555.66 hm² and 169.66 hm² respectively, making up 7.54% of the total land area in the study region. The ‘two horizontal’ section refers to the ecological protection zone created by the forested area north of Maoping Village and the contiguous forest land from Zhongshan Village to Chaoying Village to Yongfeng Village. On the other hand, the ‘three vertical’ section pertains to the ecological restoration zone formed by the western part of Maoping Village to Zhongshan Village, the southern part of Maoping Village to Chaoying Village, and the area from Chongfeng Village to Yongfeng Village to Shale Village. The ‘six stones’ serve as key EN within the ecological safety network, acting as important connectors between the northern and southern ES, strategically placed along the axes and intersections. Lastly, the ‘three area’ encompasses the state-owned forest area in the northern part of Maoping Village, the central forest area of Chaoying Village, and the northern forest area of Shale Village, creating a three-layered ecological barrier from north to south consisting of state-owned forest area, scrubland, and special economic forest. The planning framework of the HFH is characterized by ‘two verticals, three stones, and one area’, creating a synergistic pattern of internal protection and peripheral restoration (Fig. 8-HFH). The ecological restoration area covers 420.12 hm², while the ecologically critical protection area covers 49.59 hm², collectively forming the ecological safety network of the study area. The ‘two verticals’ represent significant ecological belts: one stretching from Gaole Village to the eastern part of Right7 Village, then to the eastern part of Minle Village, and finally extending to the southern part of Luojiaqiao Village; the other runs from the western part of Youqi Village to the northern and western parts of Minle Village. These two ecological zones intersect at key ‘stepping stone’ locations, serving as the core node of the ecological network in the study area. The ‘one area’ is situated between Youqi Village and Minle Village, linking tea plantations, nursery gardens, and public welfare forests, functioning as the largest ecological green core of the study area. The ESP of HJ consists of ‘one horizontal, one vertical, two rocks and one area’. The north-western area is identified as the primary zone for ecological protection, while the southern part is dedicated to ecological restoration (Fig. 8-HJ). The ‘one horizontal’ section pertains to the ecological restoration zone encompassing the southern regions of Yindongwan Village and Cha’eryan Village, located at higher altitudes. The ‘vertical’ component traverses Wuli Village, Xaigu Village, and extends to the north-western part of Cha’eryan, featuring diverse plantation forests like Platycladus orientalis and Koelreuteria bipinnata.

Ecological restoration and optimization

This paper aims to propose a set of optimization measures for the core elements of the ESP in KDC. These measures are designed to enhance the stability and anti-disturbance capabilities of the landscape pattern in KD areas. The goal is to establish a robust ESP barrier and create a strong foundation for the sustainable development of the future socio-economy.

When examining ecological restoration and protection strategies for forests in KDC, it is crucial to emphasize the significance of key areas for ecological protection. These areas not only harbor the highest species diversity and facilitate active ecological information exchange, but they are also essential for maintaining regional ecological balance and biological security. As a result, managing these areas should strictly adhere to the fundamental principle of ‘protection first, restoration second’. If the current land-use of these key areas primarily consists of forest, irrigation land, or grassland, then it is imperative to enhance protection and management measures. Destructive activities such as land development, conversion of arable land, indiscriminate deforestation, and overgrazing must be decisively eradicated. Forest conservation efforts should be intensified to encourage positive succession of scrub, leading to increased biodiversity, especially in the north-western part of HJ. In protected areas with arable land, a more precise management approach is necessary. This includes establishing ecological buffer forest belts around arable land through replanting and new planting to safeguard field ecosystems. Additionally, there should be a focus on exploring the potential of national land greening, along with transitioning the living and production methods of local residents. Strategies such as ecological migrants should be gradually implemented to reduce pressures on the natural environment, particularly in the central and western parts of SLX.

The ecological restoration area is expected to play a central role in the future KDC. The decrease in the size of this zone indicates a significant improvement in overall ecological connectivity, with restoration efforts primarily focusing on artificial intervention and complemented by natural restoration mechanisms. Specifically in the forest-irrigation restoration area, a three-dimensional composite structure should be constructed, incorporating forest, irrigation, and grass as key elements. Various forest management measures, such as transforming low-efficiency forests, restoring degraded forests, and nurturing young and medium-sized forests, should be implemented through spatial configuration optimization. During this process, existing artificial pure forests like Pinus massoniana and Cunninghamia lanceolata should gradually transition into mixed coniferous and broad forests. The focus is on enhancing forest ecosystem services, particularly in soil and water conservation, to improve green areas like the northern part of SLX and the southern part of HJ. When restoring arable land, it is important to balance economic and ecological benefits. By prioritizing areas with slopes over 25 ° for agriculture and promoting mixed agroforestry industries like Prunus salicina-Zea mays and Cerasus serrulata-Glycine max, we can enhance farmland structure, reduce ecological barriers, and support species migration and connectivity in regions like the northwestern area of HFH.

In KD areas, land fragmentation is a significant issue, exacerbating the conflict between people and land and resulting in the fragmentation of forest ES and EC. It is crucial to implement scientific planning for ES to establish direct connections between large ES, facilitating material and energy exchange, enhancing overall ecological quality, and reducing landscape fragmentation. Priority should be given to ES construction in the southern part of the SLX, the northwestern part of the HFH, and the central and northern regions of the HJ. The presence of construction sites like transport facilities and settlements poses a threat to the continuity of EC. To counter this issue, it is essential to implement a range of innovative ecological restoration measures that cater to the migration routes and ecological requirements of various species. One approach is the construction of biological corridors such as culverts and animal bridges to facilitate species migration. Additionally, leveraging unused spaces like under bridges and roadsides to create small habitats can act as ‘stepping stones’ for species migration, ultimately boosting connectivity between ES.

Discussion

The constructing an ESP in KDC forest has proven to be essential in mitigating the escalating human-land conflicts in the region. It has significantly expanded the coverage area of ES and notably enhanced the overall habitat quality. Given the habitat challenges encountered in current KDC, the ecological restoration strategy primarily focuses on artificial assisted restoration and ecological remodelling. In a related study13,55, American scholars, delved into the restoration mechanism of ES, particularly addressing ecosystem restoration in areas affected by human activities. Their proposed zonal restoration strategy aligns with the research direction of this paper. In the realm of identifying and regulating ecological restoration zones and key ecological protection zones, the research findings of Chinese scholars Yang Honghui et al.56 align well with the zoning delineation and regulatory measures discussed in this paper. However, in comparison to existing studies on KDC, many of them tend to focus solely on a single level of KD, overlooking the impact of successive levels on the overall ecosystem. Moreover, these studies primarily concentrate on evaluating the ecosystem service function within desertification management areas, neglecting a holistic analysis of the influence of human activities and natural factors. Methodologically, compared to traditional approaches for constructing ESP, this study employs the MSPA model, which more accurately identifies critical ecological nodes and offers unique advantages in landscape ecology. Zeng et al. demonstrated that the MSPA model achieves higher accuracy in identifying ecological corridors and core areas in mountain resource-based urban ecosystems57. In addition, circuit theory effectively identifies ecological corridors and key nodes by simulating species movement patterns across complex landscapes. Chen et al. applied circuit theory to identify potential ecological nodes and found significant overlap with areas of intensive human activity, indicating the theory’s effectiveness in simulating species movement in complex environments58. Zhang et al. integrated remote sensing-based ecological indices with circuit theory to construct an ecological security pattern, effectively simulating species movement in complex landscapes59.

This paper accurately identifies EN and defines key areas for ecological protection and restoration by considering the changing levels of KD through the MSPA and circuit theory. Differentiated ESP were constructed based on varying levels of KD, which include ‘two horizontals, three verticals, five stones, three areas’, ‘two verticals, three stones, one area’, ‘one horizontal, one vertical, two stones, one area’, The paper proposes corresponding ecological protection and restoration measures aimed at mitigating the tension between humans and land in KD areas, while also offering new theoretical and practical insights to enhance the ecological environment quality in the region. This study integrates ESP with the Ecological Redline Policy. It is recommended that the designated primary protection zones be included in the core area of the Ecological Redline and designated as conservation bases for karst-specific plant species, with strict development prohibitions. Primary improvement areas should correspond to general control zones within the Redline, where targeted restoration activities are permitted. This study also integrates ESP with land-use zoning. Key ecological corridors should be designated as ecological conservation areas, where road construction is prohibited from disrupting continuity and new linear projects must include wildlife passages. Stepping stone nodes should be classified as mixed-use ecological land, where forest-herb compound cultivation is allowed but planting ratios must be strictly controlled. Future restoration corridors should be designated for ecological rehabilitation, with priority given to implementing specific control measures for KD. This study further integrates ESP with KDC. Areas with mild KD generally possess strong self-recovery capacity and are considered critical ecological protection zones. Therefore, ecological protection and restoration efforts should focus on supporting natural regeneration. Measures such as forest closure, grazing and firewood harvesting restrictions help reduce disturbance and promote natural vegetation growth60. Additionally, planting locally adapted pioneer species can accelerate vegetation coverage, enhance soil retention, and prevent further soil erosion61. In areas of moderate KD, ecosystem structure and function have been significantly degraded, and natural recovery is slow; these areas are categorized as ecological restoration zones. Therefore, more proactive artificial interventions are required in these regions. Vegetation reconstruction projects are recommended, involving the planting of diverse locally adapted trees, shrubs, and herbs to build multi-layered vegetation communities. For example, in moderate KD areas, the mixed planting of Sophora davidii and Dendrocalamus latiflorus has accelerated vegetation recovery and achieved significant restoration effects62. Adding organic matter and improving soil structure to enhance fertility and water retention are also essential artificial interventions to support vegetation growth63. In areas of severe KD, ecosystems are heavily damaged, with extensive exposed rock, minimal soil, and great difficulty in vegetation recovery; these areas are designated as zones for engineering-based ecological restoration. Terrain modification is essential; measures such as terrace construction can reduce surface runoff and erosion, while topsoil addition helps increase soil depth64. Meanwhile, drought- and nutrient-poor-tolerant pioneer species should be planted, with attention to site conditions in building layered vegetation communities. For instance, a restoration model involving mixed planting of Sabina chinensis and Caragana korshinskii in severe KD areas has successfully formed a multi-layered forest structure of trees and shrubs, providing effective soil and water conservation benefits65.

Based on the above discussion, differentiated control strategies should be implemented for regions with varying levels of KD and different ES, EC, and EN types. In areas with mild KD, a strategy of “natural regeneration supplemented by artificial assistance” should be adopted. Around core areas, enclosed reforestation should be conducted for 3–5 years, with restricted grazing intensity. Establish ecological buffer forest belts wider than 20 meters around cultivated land, prioritizing dominant native species. Implement three-dimensional planting systems on sloped farmland exceeding 25°, balancing ecological and economic benefits. In moderate KD areas, carry out projects focusing on “vegetation reconstruction and soil improvement”. In fractured zones of transition areas, apply mixed-species planting, which is expected to achieve effective coverage within a few years. Conduct soil replacement projects in barrier areas, supplemented with organic fertilizers. In severe KD areas, implement comprehensive measures combining engineering restoration with pioneer species planting. In high-altitude barrier points, apply terrace conversion and reinforce with stone embankments. Use drought-tolerant economic tree species in combination with shrubs and trees, while designating wildlife corridors. For ES areas, adopt protective measures. Implement a three-tiered control system for the core area, encompassing “core protection, buffer transition, and ecological migration”. Prohibit all development activities in first-level protection zones, promote ecological relocation in second-level buffer zones, and develop understory economy in third-level relocation zones. For EC areas, apply optimization strategies. In primary corridors, implement “dual-channel” construction by reserving 30-meter-wide ecological corridors on both sides of existing roads and planting dominant species to form biological barriers. In fragmented corridors, establish ecological islands with supporting rainwater harvesting ponds. For EN areas, adopt restoration strategies. Implement projects integrating micro-topography modification and vegetation planning. Construct a multi-layered structure of trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants using drought-resistant species. In addition, first-level pinch points should be designated as ecological exclusion zones, prohibiting all forms of development. Within a 100-meter buffer zone around these areas, planting should be minimized and protective forests promoted to reduce the indirect impact of soil erosion on pinch points.

South China Karst, situated in the transitional zone between the first and second steps of the Tibetan Plateau, features unique karst mountains that give the region a distinctive appearance. However, this area is also central to the Yunnan-Guizhou-Guangxi KD concentrated contiguous area, presenting significant ecological challenges. This study focuses on three KDC forest areas with varying degrees of change, emphasizing the lack of actual hydrological observation data in these regions as a major obstacle for in-depth analysis. Hydrological factors in KD areas significantly affect vegetation restoration and soil erosion. A key aspect of ensuring ecological security in these regions lies in rebuilding the hydrological redistribution capacity that supports vegetation recovery66,67. Moving forward, it is crucial to further incorporate the analysis of hydrological factors to reveal their profound impacts on the ecological landscape and ecological security of KDC forest areas. The construction and optimization of ESP are spatially and temporally dynamic, and should be assessed over a period of at least five years. However, this study focused solely on the spatial scale in constructing and regulating ESP in KDC areas, potentially overlooking changes caused by seasonal variations, climate shifts, and human activities. As a result, the assessment of pattern stability may lack accuracy. Therefore, future research should incorporate temporal dimensions alongside spatial analysis to better understand environmental changes in KD regions. Due to data acquisition and methodology limitations, this study focuses on high speed, provincial, and county roads for road data extraction, without fully considering the impact of township and rural roads. The exclusion of township and rural roads in this study may pose ecological risks. Previous studies have shown that, compared with highways and provincial roads that create concentrated barriers, dense networks of rural roads are more likely to increase habitat fragmentation and amplify edge effects68,69. For example, unpaved rural roads can fragment salamander habitats, exerting a greater negative impact on their populations70. Therefore, future studies should incorporate data on township and rural roads to assess their effects on species distribution and migration resistance. These roads not only influence species migration paths in reality, but also introduce uncertainties in resistance value refinement and assignment. Therefore, future research should refine resistance factors, analyze the ESP system comprehensively using multi-source data and simulations, uncover the ecological spatial and temporal sequence changes, and delve into the evolution mechanism of the ESP. In future research, it is essential to clarify the development direction of the study area to achieve optimal control of the forest ecological safety network for KDC. This will contribute valuable insights and efforts to enhancing the ecological safety of South China Karst and the broader KD area through scientific planning and effective management. As this study focuses primarily on spatial outputs, we plan to incorporate additional quantitative indicators and apply statistical methods in future work to evaluate the impact of resistance factors on the identified ecological sources and corridors. Although this study employed multiple data sources and models in constructing the ecological security pattern, it lacks a systematic assessment of uncertainty. Therefore, we will apply sensitivity analysis to systematically vary resistance values and threshold distances, assessing how these changes affect ecological corridor connectivity and source identification71. In addition, the Monte Carlo simulation method was used to apply multiple random perturbations to the input parameters in order to evaluate the variability of the model outputs72. Human activities significantly impact ecological connectivity. The advancement of urbanization, expansion of transportation networks, and continuous land development are expected to intensify ecological pressures in the study area. However, our study clearly lacks a comprehensive analysis of anthropogenic pressures. Therefore, we plan to use the CA-Markov model to predict future land-use change trends, particularly the impacts of urban expansion and road construction73,74. In addition, we will apply the SLEUTH model to simulate the dynamic processes of urban development and analyze the long-term impacts of different planning strategies on ecological connectivity75. By integrating the CA-Markov and SLEUTH models, we aim to simulate changes in ecological connectivity under various planning scenarios.

-

1.

Found that forest patch fragmentation was notably pronounced, with a worsening trend as KD intensified, leading to a significant decrease in forest area. More specifically, we isolated 45, 32, and 50 ES forest patches in the SLX, HFH, and HJ regions, respectively. These patches represented 10.62%, 5.80%, and 2.30% of the total area in each respective study area.

-

2.

Revealed as the level of KD increases, the proportion of islets in the ecological landscape is also increasing, while the proportion of pore space is decreasing. This shift results in reduced connectivity between forest regions and hinders the flow of ecological elements between them, ultimately leading to significant ecological degradation within the forest.

-

3.

In the SLX, this paper successfully extracted a total of 108 EC, which had a total length of 109.34 km. At the same time, 47 EN with a total area of 22.05 hm² and 20 EBS with a total area of 555.66 hm² were identified. In the HFH, we extracted 68 EC with a total length of 59.44 km. In addition, 10 EN with a total area of 4.14 hm² and 10 EBS with a total area of 420.12 hm² were identified. Finally, in the HJ, we extracted a total of 113 EC with a total length of 128.10 km, which contained 28 EN with a total area of 24.57 hm², and 12 EBS with a total area of 379.53 hm².

-

4.

In the context of different levels of KDC, significant spatial differences were observed in forest ESP. Within the study areas of SLX, HFH, and HJ, key areas for ecological protection were determined to be 169.66 hm², 49.59 hm², and 101.61 hm², while ecological restoration areas were identified as 555.66 hm², 420.12 hm², and 379.53 hm², respectively. By focusing on these key areas, a distinct ESP pattern was successfully established, illustrating layouts of ‘two horizontals, three verticals, five stones, and three areas’, ‘two verticals, three stones, and one area’, and ‘one horizontal, one vertical, two stones, and one area’ for each respective study area.

Data availability

Data are available from the authors upon request.

References

Li, Z. & Liu, X. Ecological security issues in China. Ecol Econ 18, 10–13 (2002).

Jiang, Y. China’s answer to how to manage ecological problems from the ground up. People’s. Trib. 1, 28–31 (2021).

Ye, X., Zou, C., Liu, G., Lin, N. & Xu, M. Main research contents and advances in the ecological security pattern. Acta Ecologica Sin. 38, 3382–3392 (2018).

Segan, D. B., Murray, K. A. & Watson, J. E. M. A global assessment of current and future biodiversity vulnerability to habitat loss-climate change interactions. Glob. Ecol. Conserv 5, 12–21 (2016).

Moarrab, Y., Salehi, E., Amiri, M. J. & Hovidi, H. Spatial-temporal assessment and modeling of ecological security based on land-use/cover changes (case study: Lavasanat watershed). Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 19, 3991–4006 (2022).

Zhou, D., Lin, Z., Ma, S., Qi, J. & Yan, T. Assessing an ecological security network for a rapid urbanization region in Eastern China. Land Degrad. Dev. 32, 2642–2660 (2021).

Feng, Q. et al. Accelerate Construction of New Pattern of Ecological Protection in Northwest China. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 37, 1457–1470 (2022).

Ma, K., Fu, B., Li, X. & Guan, W. The regional pattern for ecological security (RPES): the concept and theoretical basis. Acta Ecologica Sin. 24, 761–768 (2004).

Pneg, J., Zhao, H., Liu, Y. & Wu, J. Research progress and prospect on regional ecological security pattern construction. Geographical Res. 36, 407–419 (2017).

Ma, X. et al. Research on ecological security pattern construction in vulnerable ecological region. Acta Ecologica Sin. 43, 9500–9513 (2023).

Knaapen, J., Scheffer, M. & Harms, B. Estimating habitat isolation in landscape planning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 23, 1–16 (1992).

Elbasit, M. A. M. A., Knight, J., Liu, G., Abu-Zreig, M. M. & Hasaan, R. Valuation of Ecosystem Services in South Africa, 2001–2019. Sustainability [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2024 Jun 7];13. Available from: http://ideas.repec.org/a/gam/jsusta/v13y2021i20p11262-d654821.html.

Sylvain, Z. A., Branson, D. H., Rand, T. A., West, N. M. & Espeland, E. K. Decoupled recovery of ecological communities after reclamation. PeerJ 7, e7038 (2019).

Yu, K., Wang, S. & Li, D. Regional ecological security pattern: A case study of Beijing. Beijing: China construction industry publishing house. 1–105 (2012).

Chen, X. & Zhou, C. Review of the studies on ecological security. Prog. Geogr. 8–20 (2005).

Chen, J., Wang, S. & Zou, Y. Construction of an ecological security pattern based on ecosystem sensitivity and the importance of ecological services: A case study of the Guanzhong Plain urban agglomeration, China. Ecol. Indic. 136, 108688 (2022).

Wang, C., Yu, C., Chen, T., Feng, Z. & Wu, K. Can the establishment of ecological security patterns improve ecological protection? An example of Nanchang, China. Sci. Total Environ. 740, 140051 (2020).

Yang, S., Zou, C., Shen, W., Shen, R. & Xu, D. Construction of ecological security patterns based on ecological red line: A case study of Jiangxi Province. Chin. J. Ecol. 35, 250–258 (2016).

Yao, C. et al. Evaluation of ecological security pattern and optimization suggestions in Minjiang River Basin based on MCR model and gravity model. Acta Ecologica Sin. 43, 7083–7096 (2023).

Xiao, Y., Zhou, X., Jiang, X., Zhang, J. & Li, H. Research on ecological security maintenance of Guiyang City based on evaluation of ecosystem service function. Ecol. Sci. 39, 244–251 (2020).

Meng, J., Zhu, L., Yang, Q. & Mao, X. Building ecological security pattern based on land use: a case study of Ordos, Northern China. Acta Ecologica Sin. 32, 6755–6766 (2012).

Cui, X., Deng, W., Yang, J., Huang, W. & Vries, W. T. D. Construction and optimization of ecological security patterns based on social equity perspective: A case study in Wuhan, China. Ecol. Indic. 136, 108714 (2022).

Du, Y., Hu, Y., Yang, Y. & Peng, J. Building ecological security patterns in southwestern mountainous areas based on ecological importance and ecological sensitivity: A case study of Dali Bai Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan Province. Acta Ecologica Sin. 37, 8241–8253 (2017).

Yang, S., He, W., Wang, J., Li, H. & Yao, Y. Ecological security pattern construction in Lijiang River basin based on MCR model. China Environ. Sci. 43, 1824–1833 (2023).

Wang, Z. et al. Identification and optimisation strategy of ecological security pattern of Oasis in Xinjiang based on ecosystem service function: Taking Baicheng County as an example in Xinjiang based on ecosystem service function: Taking Baicheng County as an example. Acta Ecologica Sin. 42, 91–104 (2022).

Chen, J. et al. Construction of ecological network in Fujian Province based on Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis. Acta Ecologica Sin. 43, 603–614 (2023).

Pan, J. & Wang, Y. Ecological security evaluation and ecological pattern optimization in Taolai River Basin based on CVOR and circuit theory. Acta Ecologica Sin. 41, 2582–2595 (2021).

Liu, X., Shu, J. & Zhang, L. Research on applying minimal cumulative resistance model in urban land ecological suitability assessment: as an example of Xiamen City. Acta Ecologica Sin. 30, 421–428 (2010).

Huang, M., Yue, W., Feng, S. & Cai, J. Analysis of spatial heterogeneity of ecological security based on MCR model and ecological pattern optimization in the Yuexi county of the Dabie Mountain Area. J. Nat. Resour. 34, 771–784 (2019).

Yi, L., Sun, Y., Yin, S. & Wei, X. Construction of Ecological Security Pattern: Concept, Framework and Prospect. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 31, 845–856 (2022).

Chen, L., Sun, R., Sun, T. & Yang, L. Eco⁃security pattern building in urban agglomeration: conceptual and theoretical thinking conceptual and theoretical. Acta Ecologica Sin. 41, 4251–4258 (2021).

Waiyasusri, K. & Wetchayont, P. Assessing Long-Term Deforestation In Nam San Watershed, Loei Province, Thailand Using A Dyna-Clue Model. Geogr., Environ., sustainability 13, 81–97 (2020).

Waiyasusri, K. Monitoring the Land Cover Changes in Mangrove Areas and Urbanization using Normalized Difference Vegetation Index and Normalized Difference Built-up Index in Krabi Estuary Wetland, Krabi Province, Thailand. ResearchGate 43, 1–16 (2021).

Tan, H., Zhang, J. & Zhou, X. Construction of Ecological Security Patterns Based on Minimum Cumulative Resistance Model in Nanjing City. BSWC 40, 282–288 (2020).

Waiyasusri, K. & Tananonchai, A. Spatio-temporal development of coastal tourist city over the last 50 years from landsat satellite image perspective in takua pa district, phang-nga province, thailand. ResearchGate 43, 937–945 (2022).

Chen, Y., Rong, L., Xiong, K., Feng, M. & Cheng, C. Spatiotemporal changes and driving factors of ecosystem services between karst and non-karst World Heritage sites in Southwest China. Herit. Sci. 12, 278 (2024).

Yuan, D. Karst in southwest China and its comparison with karst in north China. Quatern. Sci. 352–361 (1992).

Zhang, S., Xiong, K., Min, X. & Zhang, S. Demographic shrinkage promotes ecosystem services supply capacity in the karst desertification control. Sci. Total Environ. 917, 170427 (2024).

Yang, M. On the fragility of karst environment. Yunnan Geogr. Environ. Res. 21–29 (1990).

Xiong, K., Kong, L., Yu, Y., Zhang, S. & Deng, X. The impact of multiple driving factors on forest ecosystem services in karst desertification control. Front Glob. Change 6, 1220436 (2023).

Su, W., Zhu, W. & Xiong, K. Stone desertification and eco-economics improving model in guizhou karst mountain. Carsologica Sinica. 21–26 (2002).

Xiong, K. et al. editors. The typical study on RS-GIS of karst desertification—with a special reference to Guizhou Province. (Beijing: Geology Press, 2002).

Guo, Y., Ma, X., Zhu, Y., Chen, D. & Zhang, H. Research on Driving Factors of Forest Ecological Security: Evidence from 12 Provincial Administrative Regions in Western China. Sustainability 15, 5505 (2023).

Zhang, S. et al. Research Progress on Ecological Carrying Capacity and Ecological Security, and Its Inspiration on the Forest Ecosystem in the Karst Desertification Control. Forests 15, 1632 (2024).

Li, Q., Tang, L., Qiu, Q., Li, S. & Xu, Y. Construction of urban ecological security pattern based on MSPA and MCR Model: a case study of Xiamen. Acta Ecologica Sin. 44, 2284–2294 (2024).

Liu, J., Li, S., Fan, S. & Hu, Y. Identification of territorial ecological protection and restoration areas and early warning places based on ecological security Pattern: a case study in Xiamen⁃Zhangzhou⁃Quanzhou Region. Acta Ecologica Sin. 41, 8124–8134 (2021).

Chen, D., Lan, Z. & Li, W. Construction of Land Ecological Security in Guangdong Province From the Perspective of Ecological Demand. J. Ecol. Rural Environ. 35, 826–835 (2019).

Jin, L., Xu, Q., Yi, J. & Zhong, X. Integrating CVOR-GWLR-Circuit model into construction of ecological security pattern in Yunnan Province, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res 29, 81520–81545 (2022).

Wang, Q., Fu, M., Wei, L., Han, Y. & Quan, Z. Urban ecological security pattern based on source-sink landscape theory and MCR model: A case study of Ningguo City, Anhui Province. Acta Sci. Circumstantiae 32, 4546–4554 (2016).

Huang, L., Wang, D. & He, C. Ecological security assessment and ecological pattern optimization for Lhasa city (Tibet) based on the minimum cumulative resistance model. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res Int 29, 83437–83451 (2022).

Han, R. et al. Construction of Ecological Security Pattern in Beijing City Based on Minimum Resistance Model. BSWC 42, 95–102 (2022).

Zhang, B. et al. Driving Mechanisms of Ecological Suitability Index in the Yellow River Basin from 1990 to 2020. Sustainability 17, 1307 (2025).

Jin, X., Wei, L., Wang, Y. & Lu, Y. Construction of ecological security pattern based on the importance of ecosystem service functions and ecological sensitivity assessment: a case study in Fengxian County of Jiangsu Province, China. Environ., Dev. Sustainability 23, 563–590 (2021).

Xiang, A. et al. Diagnosis and restoration of priority area of territorial ecological restoration in Plateau Lake Watershed. Acta Ecologica Sin. 43, 6143–6153 (2023).

Zhang, S., Xiong, K., Qin, Y., Min, X. & Xiao, J. Evolution and determinants of ecosystem services: insights from South China karst. Ecol. Indic. 133, 108437 (2021).

Yang, H. et al. Construction of ecological security pattern based on remote sensing urban ecological index and circuit theory: a case study of Guangzhou City, Guangdong Province of southern China. J. Beijing Forestry Univ. 45, 127–139 (2023).

Zeng, L., Li, R. Y. M. & Du, H. Modeling the Ecological Network in Mountainous Resource-Based Cities: Morphological Spatial Pattern Analysis Approach. Buildings 15, 1388 (2025).

Chen, B., Liu, X. & Liu, J. Construction and optimization of ecological security patterns in Chinese black soil areas considering ecological importance and vulnerability. Sci. Rep. 15, 12142 (2025).

Zhang, L., Liu, Q., Wang, J., Wu, T. & Li, M. Constructing ecological security patterns using remote sensing ecological index and circuit theory: A case study of the Changchun-Jilin-Tumen region. J. Environ. Manag. 373, 123693 (2025).

Li, K. et al. Effect of different artificial restoration methods of Karst rocky desertification on community composition and niche characteristics of woody populations in Shilin scenic area. Acta Ecologica Sin. 40, 4641–4650 (2020).

Zheng, W. et al. Vegetation restoration enhancing soil carbon sequestration in karst rocky desertification ecosystems: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 370, 122530 (2024).

Su, M. Rocky desertification of excellent species–as beans. D. Pop. Sci. Technol. 18, 75–76 (2016).

Gerke, J. The Central Role of Soil Organic Matter in Soil Fertility and Carbon Storage. Soil Syst. 6, 33 (2022).

Bai, J., Yang, S., Zhang, Y., Liu, X. & Guan, Y. Assessing the Impact of Terraces and Vegetation on Runoff and Sediment Routing Using the Time-Area Method in the Chinese Loess Plateau. Water 11, 803 (2019).

Duan, H. et al. Vegetation restoration model and suggestions on its optimization in rocky desertification areas of Yunnan Province. Carsol. Sin. 43, 137–146 (2024).

Zhang, S., Xiong, K., Min, X. & Zhu, D. Vegetation vulnerability in karst desertification areas is related to land–atmosphere feedback induced by lithology. Catena 247, 108542 (2024).

Cai, L., Xiong, K., Liu, Z., Li, Y. & Fan, B. Seasonal variations of plant water use in the karst desertification control. Sci. Total Environ. 885, 163778 (2023).

Pauwels, F. Gulinck. Changing minor rural road networks in relation to landscape sustainability and farming practices in West Europe. Agriculture, Ecosyst. Environ. 77, 95–99 (2000).

Coffin, A.W. et al. The Ecology of Rural Roads: Effects, Management, and Research. Issues in Ecology, Report No. 23. Ecological Society of America. 36 p. (2021).

Ochs, A. E., Swihart, R. K. & Saunders, M. R. A comprehensive review of the effects of roads on salamanders. Landsc. Ecol. 39, 77 (2024).

Pianosi, F. et al. Sensitivity analysis of environmental models: A systematic review with practical workflow. Environ. Model. Softw. 79, 214–232 (2016).

Garg, N., Yadav, S. & Aswal, D. K. Monte Carlo Simulation in Uncertainty Evaluation: Strategy, Implications and Future Prospects. MAPAN 34, 299–304 (2019).

Hu, X. et al. Exploring the predictive ability of the CA–Markov model for urban functional area in Nanjing old city. Sci. Rep. 14, 18453 (2024).

Akin, A., Aliffi, S. & Sunar, F. Spatio-temporal Urban Change Analysis and the Ecological Threats Concerning The Third Bridge in Istanbul City. ResearchGate 7, 9–14 (2025).

Yin, H. et al. Assessing Growth Scenarios for Their Landscape Ecological Security Impact Using the SLEUTH Urban Growth Model. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 142, 05015006 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the China Overseas Expertise Introduction Program for Discipline Innovation (Grant No. D17016), the Major Special Project of Provincial Science and Technology Program of Guizhou Province (Grant No.6007 2014 QKHZDZXZ) and the Project of Geographical Society of Guizhou Province (Grant No.2020HX05).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Song Zhang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data collection and analysis, Writing-original draftpreparation. Yu Zhang: Conceptualization, Reviewing and Editing. Kangning Xiong: Conceptualization, Reviewing and Editing, Funding acquisition. Yanghua Yu: Writing-Review&Editing, Supervision. Cheng He: Date Curation, Resources, Writing-Review. Shihao Zhang: Methodology, Visualization. Zhaohua Wang: Date Curation, Investigation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This work does not raise any ethical issues. We are grateful for the valuable reviewers comments which helped in revising this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, S., Zhang, Y., Xiong, K. et al. Construction of forest ecological security patterns based on MSPA model and circuit theory in the Desertification Control forests in South China Karst. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 432 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01973-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01973-8