Abstract

The Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal, the world’s longest man-made waterway, has had a profound impact on Chinese social, economic, and cultural development, forming a typical linear cultural belt. This study focuses on the urban heritage of cities along its Jiangsu section. Social media data from platforms such as Douyin and Weibo were collected, and a quantitative evaluation system was developed using the Entropy Weight-TOPSIS method to assess the cultural transmission ability (CTA) of heritage sites and analyze key influencing factors. Spatial analysis methods were applied to examine distribution patterns. The results show that: (1) secondary dissemination indicators, including Weibo reposts and Douyin favorites and shares, contribute over 43% to CTA; (2) CTA exhibits spatial clustering, mainly in Suzhou, Wuxi, and Yangzhou; (3) CTA is positively correlated with heritage site concentration, and well-developed transportation infrastructure promotes transmission; (4) architectural heritage has significantly higher CTA than archaeological and burial sites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Grand Canal of China stretches from Tongzhou in the north to Hangzhou in the south, running through several key provinces and municipalities in eastern China, including Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shandong, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang. With a total length of 1794 kilometers, it is the longest man-made canal in the world1,2. First constructed during the Spring and Autumn period, the canal has witnessed over 2500 years of Chinese history and has played a significant role in the country’s social, historical, economic, and political development. Along its course, it has formed an important linear cultural belt3,4. In 2014, the Grand Canal was inscribed on the World Heritage List, further highlighting its cultural value.

As the oldest artificial waterway in the world, the Grand Canal has long provided vital support in water transportation and ecological services for the regions along its route. It has long served as a central theme in scholarly research. Huang et al.5 examined the Canal’s influence on the rise and fall of ancient Chinese cities using Kaifeng as a case study. Fang6 examined the characteristics of the Grand Canal’s water transport system and analyzed its functional significance in contemporary Jiangsu. Xu et al.7 assessed the ecological service function of the Jiangsu section of the Grand Canal from perspectives such as water conservation and grain supply, revealing a clear spatial heterogeneity in ecological value and a continuous decline over time. Zhang8,9 and Xu10 assessed the ecosystem service values of heritage sites along the Canal using tools such as InVEST and GIS, as well as the equivalent factor method.

Meanwhile, research on the heritage of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal has become increasingly enriched. Ge et al.11 employed kernel density analysis and the center-of-gravity shift model to explore the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of heritage. Yang12 combined kernel density and standard deviation ellipse analysis to reveal the spatiotemporal patterns of traditional operas along the Canal. Li13 analyzed the distribution patterns of intangible heritage within the Canal basin from both natural and social perspectives. Huang et al.14 studied the spatiotemporal evolution of 104 heritage sites in the Suzhou section and found that the degree of site clustering increased since the Sui and Tang dynasties, peaking during the Qing dynasty, and was significantly influenced by the Canal’s geographical features. Zhou et al.15 analyzed the influence of geographic, cultural, and watershed-related factors on traditional villages along the Jiangsu–Zhejiang section of the Canal. Shi et al.16 further revealed that socioeconomic factors, particularly urbanization, had a significant impact on the distribution of intangible heritage. Zhang et al.17 applied spatial autocorrelation analysis and evolutionary tree modeling to examine the clustering patterns and evolution of intangible heritage. Chen et al.18 explored the spatiotemporal distribution of intangible heritage and its relationship with tourism, indicating that heritage distribution is affected by natural, socioeconomic, and policy factors, and is positively correlated with tourism development. Overall, research on the Grand Canal’s heritage has gradually formed a systematic theoretical framework, ranging from spatiotemporal distribution patterns to the underlying natural and social influencing factors.

In recent years, research on heritage protection has gradually expanded from the physical preservation of heritage to the exploration of its cultural value and transmission ability. Rong et al.19 using the Hangzhou section of the Grand Canal as a case study, examined which historical works and sites are closely related to the Canal’s core values. Vidaurre-Rojas et al.20 investigated the cultural value of the Lamas heritage in Peru through social media and explored the potential of enhancing its CTA via digital platforms. However, current research lacks quantitative evaluations based on big data. Establishing a scientific evaluation framework could offer an objective foundation for policy-making21.

This study collects social media data related to heritage sites in cities along the Jiangsu section of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal. Using the Entropy Weight-TOPSIS method, it conducts an objective and quantitative evaluation of each site’s CTA. The results are compared with those of cluster analysis, internet search indices, and questionnaire surveys. From a multi-dimensional perspective, the study explores the key factors influencing CTA and proposes corresponding enhancement strategies, aiming to provide a theoretical foundation for the effective protection of heritage.

Method

Study objects and data sources

As a World Heritage Sites (WHS), the Grand Canal comprises a total of 85 World Heritage sites and 31 river sections along its entire route. The Jiangsu section alone includes 36 heritage sites and 14 segments of the canal. Historically, Jiangsu has been characterized by a dense network of waterways and a well-developed grain transport system, which has made significant contributions to north-south connectivity in China22. today, sections of the canal in Jiangsu remain navigable. Centuries of north-south interaction have enabled cities along the Jiangsu section of the Grand Canal to accumulate a wealth of heritage23. These heritage sites not only bear witness to the historical evolution of the Grand Canal but also play a profound role in shaping the development of cities along its route.

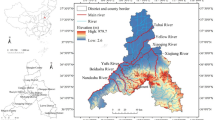

This study selects 205 National Key Cultural Relics Protection Units (NKU) and 36 World Heritage Sites (WHS) located along the Jiangsu section of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal as the research objects (Fig. 1), including 12 sites that are dual-listed (DUAL). Special cases such as Slender West Lake in Yangzhou are also considered. Although Slender West Lake is recognized as a WHS for its cultural landscape, it encompasses multiple distinct heritage sites such as Lotus Bridge, White Pagoda, and Xu Garden. Therefore, both the lake as a whole and its constituent heritage elements are analyzed separately.

CTA refers to the capacity of a heritage site to disseminate the culture it represents. In the past, evaluating this capability has been challenging due to the limited availability and questionable authenticity of relevant data. However, in the digital era, the rapid development of the Chinese internet has provided new opportunities for cultural dissemination24. Using social media data to assess the CTA of heritage sites offers greater accessibility and authenticity. Given that short video platforms have become popular social tools among younger generations, this study incorporates data not only from traditional text-and-image-based media such as Sina Weibo, but also from Douyin, the most widely used short video platform in China. All data were collected for the entire calendar year of 2023. Using the official names of each cultural heritage site as keywords, we conducted comprehensive searches on both Douyin and Sina Weibo platforms. A total of 6369 Weibo posts and 10,751 Douyin videos were retrieved.

For Douyin, the collected indicators included the number of videos, comments, likes, shares, and saves. For Weibo, we collected the number of posts, replies, likes, and shares. To ensure data quality, we applied a manual screening process to remove entries that: (1) lacked cultural or historical relevance; (2) were associated with commercial entities bearing similar names; or (3) were duplicates or low-quality content.

The final dataset includes data on all 229 heritage sites. The five sites shown in Fig. 2 serve solely as illustrative examples for how CTA indicators were derived.

Entropy weight-TOPSIS method

The entropy weight method combined with the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to an Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) is a widely used approach for multi-indicator evaluation. Peng et al.25 applied this integrated method to quantify the vulnerability of earthen sites. Since then, it has been successfully adopted in various fields such as wall weathering assessment26, disease diagnosis of earthen ruins27, and green development evaluation systems28, demonstrating strong applicability and scientificity. In this study, based on statistical data from Douyin and Weibo, the entropy weighted-TOPSIS method is employed to calculate a comprehensive cultural transmission score for each heritage site. The specific technical route is illustrated in Fig. 3.

With the promotion, application, and in-depth study of entropy theory across various disciplines, the concept of entropy was further developed throughout the mid-20th century29. In 1948, Shannon proposed a mathematical formulation of entropy, which quantitatively describes the uncertainty of data30. In recent years, many studies have successfully applied information entropy to multi-criteria comprehensive evaluation, interpreting this uncertainty as degree of change31. The underlying idea is that the smaller the calculated entropy, the greater the degree of data variation, which indicates a higher amount of information and a more significant role in the comprehensive evaluation. therefore, a higher weight is assigned. Consequently, the “degree of uncertainty” or “degree of variability” of the data can be used as the basis for weighting indicators in the entropy right method. Assuming that there are m evaluation objects and each object is assessed by n indicators, the steps of the calculation are as follows32:

Step 1: Construct the Evaluation Matrix \({X}_{{mn}}\)

Step 2: Data Normalization

Since the original data for each indicator may have different dimensions and units, direct comparison and analysis can be challenging. Therefore, it is necessary to normalize the data, as shown in Eq. (2).

\({x}_{{ij}}\) denotes the value in the ith row and jth column of the matrix, representing the value of the jth evaluation indicator for the ith object. \({x}_{\max }\) and \({x}_{m{in}}\) refer to the maximum and minimum values of the jth indicator column, respectively.

using Eq. (3) to obtain \({p}_{{ij}}\), the feature weight of the ith evaluation object under the jth indicator:

Step 3: Calculate the Information Entropy

After obtaining the feature weights, Eq. (4) is used to calculate the information entropy (\({E}_{j}\)) of each indicator, where \({p}_{{ij}}{ln}({p}_{{ij}})=0\) is taken when \({p}_{{ij}}\) is equal to 0.

Finally, the weight matrix \(W=\left[\begin{array}{cccc}{w}_{1} & {w}_{2} & \cdots & {w}_{n}\end{array}\right]\) is calculated based on the entropy values of each indicator. The weights of the indicators are denoted as \(\begin{array}{cccc}{w}_{1}\,{w}_{2}\,\cdots\,{w}_{n}\end{array}\), and the calculation formula is as shown in Eq. (5):

The TOPSIS method is a classic indicator-based decision making method first introduced by Hwang and Yoon in 198133. The basic principle is to identify the best and worst solutions among a limited set of alternatives from a standardized original matrix. Then, the relative closeness of each alternative to the ideal and negative ideal solutions is calculated based on the distance between each target and these solutions. This calculation is used as a comprehensive evaluation of the superiority or inferiority of the research targets. Whether dealing with small or large sample data, the TOPSIS method can effectively utilize the original data to accurately reflect the distance between evaluation objects. The calculation process is explained in detail as follows34.

Step 1: Development of a Weighted Normalization Matrix

Multiplying the normalized matrix by the weights of each indicator results in the weighted normalized decision matrix U. The element in the ith row and jthcolumn of this matrix is denoted as \({u}_{{ij}}\):

\({w}_{j}\) represents the weight of the jth indicator, which is the entropy weight as shown in the previous section. \({r}_{{ij}}\) refers to the element at the corresponding position in the normalized matrix.

Step 2: Constructing the Ideal Solution Vectors

The ideal solution \({A}^{+}\) and the negative ideal solution \({A}^{-}\) are defined as:

Here:

\({r}_{j}^{+}\) is the value of the jth indicator in the ideal solution;

\({r}_{j}^{-}\) is the value of the jth indicator in the negative ideal solution.

Step 3: Calculating the Distances to the Ideal and Negative Ideal Solutions

Here: \({s}_{i}^{+}\) represents the distance between the ith alternative and the ideal solution; \({s}_{i}^{-}\) represents the distance between the ith alternative and the negative ideal solution.

Step 4: Calculating the Relative Closeness \({C}_{i}^{+}\):

The closer the relative closeness \({C}_{i}^{+}\) is to 1, the closer the alternative is to the ideal solution and the better its performance.

K-means clustering analysis

Clustering analysis is an unsupervised learning method35. In this study, we adopt K-means clustering, a method first proposed by MacQueen in 196736, The core idea of K-means is to partition a dataset into K clusters, where data points within the same cluster are as similar as possible, while those in different clusters are as distinct as possible. K-means clustering is known for its interpretability of results37.

The specific steps of K-means clustering are illustrated in Fig. 4. First, the data are preprocessed, elbow rule is used to determine the value of the hyperparameter K, which is used to determine the number of classes obtained after clustering. Next, initial cluster centers are selected, and data points are assigned to the nearest cluster center based on Euclidean distance. For each cluster, a new centroid is computed. If the centroids remain unchanged, the algorithm terminates and the clustering result is obtained; otherwise, the steps of data point assignment and centroid update are repeated until convergence is reached. The final clustering results group heritage sites with similar CTA into the same category. Furthermore, this algorithm is entirely based on objective data, which allows it to reflect, to a certain extent, the shared characteristics of heritage sites with similar levels of CTA.

Kernel density analysis

Kernel density analysis is a statistical tool commonly used to study the spatial distribution characteristics of target points within a specific geographic area38. This method estimates the influence of each sample point on its surrounding area by defining a kernel function around it, and then aggregates the influence of all points to calculate the density value at each location. The resulting density map, which resembles a contour map, provides an intuitive visualization of the spatial distribution of heritage sites within the study area. The specific formula is shown in Eq. (10).

Here: \(f\left(x\right)\) represents the kernel density; \(h\) is the bandwidth of the kernel function; \(n\) denotes the number of points within the bandwidth; \(k\left(x\right)\) is the kernel function, in which \(x-{x}_{i}\) represents the distance between point \(x\) and point \({x}_{i}.\)

Average nearest neighbor analysis

Average Nearest Neighbor (ANN) analysis is a classical method used to measure the spatial distribution patterns of point data. It is commonly applied to determine whether the spatial arrangement of data points is clustered, uniformly distributed, or random. The core concept involves calculating the average distance between each point and its nearest neighbor to assess the spatial characteristics of the dataset39. This observed average distance is then compared with the expected average distance under a theoretical random distribution to identify the distribution pattern40. The specific formula is as follows.

Here: \({d}_{i}\) is the distance from point \(i\) to its nearest neighboring point; \(n\) is the number of heritage sites within the study area; \(A\) represents the area of the study region; \(R\) is the Nearest Neighbor Ratio; \(\overline{r0}\) is the Nearest Neighbor Ratio; \(\overline{{rE}}\) is the expected ANN distance under a random distribution.

By calculating the R for each city, the degree of clustering of heritage sites can be assessed. A value of 1 serves as the threshold:

When \(R > 1\), the heritage sites in the city tend to be uniformly distributed;

When \(R=1\), the distribution tends to be random;

When \(R < 1\), the sites tend to be clustered.

Questionnaire method

The questionnaire survey is one of the key methods in social research. In this study, a questionnaire-based approach was employed to verify the scientific validity of the proposed evaluation method for the CTA of heritage sites. The questionnaire focused primarily on assessing respondents awareness and recognition of heritage sites in selected cities, aiming to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method in reflecting public awareness and cultural communication outcomes.

The survey was conducted in August 2024 using Tencent Questionnaire, an online survey platform. The questionnaire included three key dimensions: (1) the respondent’s current city of residence, (2) their familiarity with cities along the Jiangsu section of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal, and (3) their recognition of the most well-known cultural heritage sites in designated cities (including Suzhou, Wuxi, Yangzhou, Huaian, Xuzhou, Zhenjiang, Changzhou, and Suqian). A nominal scale (i.e., selection-based questions) was primarily used, and the content was developed in consultation with experts to ensure content validity.

The questionnaire was distributed online. A stratified random sampling method was used to ensure the diversity of demographic characteristics, including age, occupation, and geographic location. Participants were selected from among residents living near heritage sites, cultural event participants, and professionals working in related fields.

A total of 121 questionnaires were collected. Based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, 86 valid responses were retained for analysis.Inclusion criteria included: being 18 years or older, and completing the full questionnaire.Exclusion criteria included: completion time under 1 min, logically inconsistent answers, selecting the same option throughout, and duplicate submissions from the same IP or device.

The survey was primarily administered in cities along the Jiangsu section of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal, namely Suzhou, Wuxi, Yangzhou, Huaian, Xuzhou, Zhenjiang, Changzhou, and Suqian, with additional responses collected from individuals in other areas of Jiangsu Province.

Results

Quantitative scoring of CTA

The weights of each indicator were calculated using the entropy weight method, as shown in Table 1.

Among the various indicators related to Weibo and Douyin, the weights of total number of posts and total number of videos are relatively lower compared to engagement metrics such as likes, comments, favorites, and shares. This is because the total number of posts and videos is primarily influenced by the willingness of content creators and industry professionals to disseminate information, whereas engagement data more directly reflect public interest in heritage and the actual effectiveness of cultural transmission. Among these engagement indicators, favorites and shares carry significantly higher weights than likes and comments. Sharing is the most direct behavior in terms of information dissemination, while favoriting often reflects an intention to revisit the content or use it as a reference for future on-site visits, thereby indicating the attractiveness of the heritage site. Therefore, the indicator weights derived from the entropy weight method are in line with objective patterns, as they are calculated based on the intrinsic characteristics of the data without the need for subjective human input, thus ensuring a high level of objectivity and rationality.

By incorporating the entropy weights into the TOPSIS method, the comprehensive evaluation scores of CTA for each heritage site were calculated using the Entropy Weight-TOPSIS approach, as illustrated in Fig. 5. The top ten heritage sites in terms of CTA are: Humble Administrator’s Garden, Former Residence of Zhou Enlai, Ge Garden, Slender West Lake, Jichang Garden, Lingering Garden, Pan Gate, Qingming Bridge, He Garden, and Daming Temple. These sites are located in the cities of Suzhou, Wuxi, Yangzhou, and Huaian.

K-means clustering results

Given the large number of evaluation indicators used in this study (9 dimensions), and the significant heterogeneity between the data sourced from two different platforms, Weibo and Douyin, performing K-means clustering directly on the standardized data could be susceptible to high-dimensional features and noise. Therefore, principal component analysis (PCA) was first applied to reduce the dimensionality of the data, followed by K-means clustering, in order to enhance the stability and reliability of the clustering results.

After dimensionality reduction using PCA, the four evaluation indicators from Weibo were reduced to one principal component, and the five evaluation indicators from Douyin were likewise reduced to one. This resulted in a two-dimensional space representing each heritage site’s performance across both platforms. The K-means clustering was then performed based on these two dimensions, and the results are shown in Fig. 6a.

In the figure, each point represents a heritage site, with the horizontal axis indicating its performance on Weibo and the vertical axis indicating its performance on Douyin. A larger coordinate value implies better performance on the respective platform. Cluster 1 (orange) contains only one heritage site, Humble Administrator’s Garden, which stands out with high values across all evaluation indicators. Cluster 2 (green) includes seven heritage sites: Ge Garden, Jichang Garden, Lingering Garden, Pan Gate, Qingming Bridge, He Garden, and Daming Temple. all of which rank between 3rd and 10th. Cluster 3 (red) consists of heritage sites ranked from 11th to 22nd, while those ranked below 22nd are grouped into Cluster 4 (blue).

The clustering results reveal distinct cultural characteristics across the groups. Cluster 2 includes heritage sites primarily consisting of representative classical gardens, which are historically and culturally significant in Jiangsu. These sites are often iconic symbols of their respective cities and enjoy high public visibility, which explains their relatively higher rankings. Cluster 3 also contains garden heritage sites, but these are generally smaller in scale, less renowned, and thus demonstrate moderate CTA. Cluster 4 is composed mainly of archaeological sites, ancient tombs, and some lesser-known historical buildings, which tend to receive less public attention and exhibit weaker cultural communication performance.

Based on the above evaluation scores, a box plot was drawn with the normalized cultural transmission scores on the vertical axis and cluster categories on the horizontal axis, as shown in Fig. 6b.

Figure 6b illustrates the distribution of CTA scores across the four clusters of heritage sites. The boxes represent the interquartile range (25%−75%) of scores within each cluster, while the whiskers indicate the lower and upper quartiles outside this range. The results show that Cluster 1 contains only Humble Administrator’s Garden, with a CTA score of 1, indicating the strongest transmission power. Heritage sites in Cluster 2 have scores ranging from 0.34 to 0.65, reflecting relatively strong transmission ability. Cluster 3 includes sites with scores between 0.15 and 0.26, indicating moderate transmission ability. In Cluster 4, scores range from 0 to 0.14, suggesting relatively weak CTA.

From the perspective of individual heritage sites, the scientific validity of the evaluation method was verified by comparing the results of the K-means clustering with the ranking of CTA scores.

The clustering results based on the evaluation indicators show that the heritage site ranked first in CTA is significantly different from the others. Heritage sites ranked 3rd to 10th exhibit strong similarity in their evaluation indicators, as do those ranked 11th to 22nd and 23rd to 229th. This result indicates a high degree of consistency between the clustering outcomes and the CTA rankings, thereby demonstrating the scientific soundness of the evaluation method.

Questionnaire survey results

An analysis of the 86 valid questionnaires collected yielded the following results. First, with regard to respondents’ city of residence and familiarity with other cities, 58.1% of participants selected “None of the above”, indicating that they were from cities outside the Jiangsu section of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal. In addition, 38.4% of respondents identified Suzhou as the city they were most familiar with. This percentage is significantly higher than that for any other city, suggesting that Suzhou enjoys relatively high recognition among the participants. The survey results concerning respondents’ level of recognition of heritage sites in each city are presented in Table 2.

Including respondents whose household registration is outside the study area may introduce potential bias; however, it also helps reduce the influence of local residents’ over-familiarity with their hometowns, which could otherwise bias the validation of the evaluation results.

To further validate the evaluation results, the overall CTA of each city was compared with online search interest using Baidu Index and Juliang Index data, based on the search phrase “city name + cultural tourism.” As shown in Fig. 7, Suzhou again ranked highest in all three data sources. Wuxi, Yangzhou, and Huaian followed, while Suqian and Changzhou ranked lowest.

Except for Huaian and Yangzhou, the trends of public search interest and questionnaire data were consistent with the evaluation scores, demonstrating the robustness of the proposed method. Huaian’s elevated scores are likely influenced by the unique political and commemorative significance of the Former Residence of Zhou Enlai, while Yangzhou may have a relatively lower calculated score despite high public search interest, possibly because visitors tend to perceive the city’s cultural experience as a whole, overlooking in-depth engagement with individual heritage sites.

Spatial distribution of urban heritage

From a macro perspective, the spatial distribution of heritage sites in cities along the Jiangsu section of theBeijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal was analyzed using the ANN method. The resulting ANN ratio was 0.42, which is less than 1, indicating that the distribution of heritage sites in these cities is relatively clustered. With the aid of GIS, kernel density estimation was conducted on the heritage sites, and the resulting kernel density map is shown in Fig. 8. As illustrated in the figure, heritage sites along the Jiangsu section of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal are relatively concentrated in Suzhou, Wuxi, Yangzhou, Huaian, and Xuzhou.

The results of the ANN analysis for the spatial distribution of heritage sites in each city along the canal are presented in Table 3. Among the eight major cities analyzed, most exhibit relatively low ANN ratios, indicating a high degree of spatial clustering of heritage sites.

However, Suqian stands out with a significantly higher ANN ratio value of 1.70, suggesting a more dispersed distribution. This can be attributed to several factors. First, Suqian is a relatively young city in terms of administrative establishment, and it has identified and preserved fewer cultural heritage sites compared to other cities—only seven in total. Notably, three of these are prehistoric sites related to early human activity, which are often located in remote or rural areas rather than within the urban core.

Data structure characteristics of urban heritage

Heritage is a vital component of a city’s cultural depth. According to statistics, Suzhou has the highest number of heritage sites along the Jiangsu section of the Grand Canal, with a total of 60, while Suqian has the fewest, with only 7. The number of sites in other cities decreases sequentially. Figure 9 presents both the number of heritage sites and the highest CTA score for each city. Generally, a greater number of heritage sites positively contributes to CTA, as it reflects the abundance of a city’s cultural resources.

In addition, a curve was plotted using the cultural transmission scores of heritage sites in each city as the horizontal axis and probability density as the vertical axis, as shown in Fig. 10. The area under the probability density function (PDF) curve represents the probability of scores falling within a specific interval. As the interval narrows to a particular value and its neighborhood, the area under the curve can be interpreted as the probability of that specific value occurring. If the corresponding point on the curve is the highest, this value is considered the most probable score, referred to hereafter as the maximum probability score.

Further analysis reveals that the number of heritage sites, the Maximum Probability Score, and the Maximum Heritage Score are all positively correlated with the overall CTA of urban heritage in each city, as shown in Fig. 11. Suzhou, which has the highest number of heritage sites, also achieves the highest maximum probability score and maximum score, thereby ranking first in overall CTA among the studied cities. In contrast, Suqian has the fewest heritage sites, the lowest maximum probability score, and the lowest maximum score, resulting in the weakest overall CTA. Comparatively, although Wuxi’s maximum probability score and maximum score are lower than those of Huaian, its significantly higher number of heritage sites leads to a higher overall score. A similar pattern is observed in the comparison between Wuxi and Yangzhou. This highlights the important role that the quantity of heritage plays in shaping overall CTA of a city. However, enhancing overall CTA of a city relies on more than just the number of heritage sites. For instance, although Xuzhou has more heritage sites than Huaian, its overall CTA is lower. This phenomenon can be attributed to three main factors. First, the numerical advantage is not overwhelming, Xuzhou has 27 sites compared to Huaian has 25. Second, the composition of Xuzhou’s heritage leans heavily toward burial sites and archaeological sites, each accounting for approximately one-third of its total, both of which exhibit relatively low transmission ability across the study area. Third, Huaian has successfully built a strong cultural identity around the Former Residence of Zhou Enlai, leveraging it as a symbolic heritage brand, whereas Xuzhou lacks comparable cultural branding. This analysis suggests that a high level of CTA requires not only a sufficient number of heritage sites but also the presence of representative heritage sites and supportive contributions from other heritage assets.

Figure 12 presents the fitted relationship between the ranking of heritage sites and their CTA scores within the study area. Subfigures b- i illustrate the relationship between the rankings and scores of heritage sites in individual cities, while subfigure a shows the overall trend across all cities along the Jiangsu section of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal. It is evident that, both at the city level and across the entire study region, the CTA scores tend to follow a near-negative exponential relationship with the heritage rankings. Therefore, the fitting function is expressed as: \(y={\rm{a}}{e}^{{bx}}+c\).

In this model, the intercept term \(c\) represents the theoretical minimum CTA score. It was fixed at zero based on empirical observations, as all cities in the study area contain heritage sites with virtually no CTA, with their CTA scores not exceeding 0.0018. \(b\) denotes the rate of decline; the greater the value of \(b\), the faster the decrease. \(a\) is the initial decay score. Since there is no heritage site ranked 0 in this study, \(a\) is calculated as \(a={y}_{1}{e}^{-b}\), where \({y}_{1}\) is the CTA score of the most representative heritage site in each city.

The area under the curve represents the theoretical overall CTA of a city. It corresponds to the definite integral of the fitted function over the interval \(\left[1,{x}_{m}\right]\), where \({x}_{m}\) denotes the number of heritage sites in the city:\({\int }_{1}^{{x}_{m}}a{e}^{{bx}}{dx}=\frac{a}{b}({e}^{b{x}_{m}}-{e}^{b})\).

Therefore, increasing the number of heritage sites, raising the maximum heritage score, and reducing the decay rate \(b\) (in other words, increasing the maximum probability score) can all effectively enhance the overall CTA of a city. This finding further supports the conclusions discussed earlier.

In terms of the data structure, increasing the number of heritage sites in a city can effectively enhance its overall CTA. Therefore, discovering and preserving more heritage sites is key to boosting CTA. Cities that possess prominent heritage sites should take these sites as foundations to develop iconic cultural symbols for the city. Enhancing the CTA of the city’s top heritage sites can ultimately lead to an overall improvement in the CTA of urban heritage. In addition to establishing cultural icons, enhancing the promotion of heritage sites with moderate CTA can further improve the overall CTA of urban heritage.

Discussion

CTA is influenced by various factors, including transportation conditions, spatial distribution, and the categories of heritage sites. This study discusses the CTA of heritage sites in relation to these factors.

Spatial factors play an important role in influencing the CTA of heritage.Based on the results from kernel density estimation, ANN analysis, and the evaluation of overall CTA, It is evident that heritage sites along the Jiangsu section of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal are primarily concentrated in a few cities with higher scores, specifically Suzhou, Wuxi, Yangzhou, Huaian, and Xuzhou (Fig. 8). This concentration of heritage resources is not only reflected in their quantity but also provides a strong foundation for cultural transmission.

In particular, Suzhou exhibits both a high kernel density and a low ANN ratio, indicating that it hosts a large number of heritage sites that are closely clustered together. This observation supports our earlier conclusion that a greater number of heritage sites enhances CTA, and that spatial clustering further facilitates cultural dissemination.

To further validate this conclusion, the ANN ratio of each city from Table 3 was plotted on the horizontal axis, while the overall CTA score was plotted on the vertical axis to generate Fig. 13. Using least squares regression, a negative exponential function curve was fitted, indicating a negative exponential relationship between the ANN ratio and the overall CTA score. This suggests that, within the study area, the more spatially clustered the heritage sites are, the higher the overall CTA of urban heritage tends to be.

The CTA of heritage sites is influenced by surrounding transportation conditions. In this study, GIS technology was employed to model the road networks of cities along the Jiangsu section of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal. A 5-kilometer buffer zone was established around each heritage site to calculate the local road network density. The results were plotted with road network density on the horizontal axis and CTA on the vertical axis, as illustrated in Fig. 14.

In Fig. 14, each dot represents a single heritage site, most of which are clustered in the lower-right corner of the graph. This distribution suggests that cultural transmission requires a certain level of support from transportation infrastructure. To further illustrate this relationship, an auxiliary envelope line was added to encompass the majority of the data points. All sites fall below this line except for the Former Residence of Zhou Enlai. In addition to being a tourist attraction, this site frequently serves as a destination for educational visits by schools and enterprises from surrounding cities. Its CTA is not solely rooted in its cultural significance but is also reinforced by the reverence of Chinese people for national leaders.

Although some heritage sites located in areas with well-developed road networks exhibit relatively low CTA, overall, the transmission of heritage is still constrained by road network density. The intercept of the auxiliary line on the y-axis is 0.1. This indicates that, within the study area, a heritage site can still possess a certain level of CTA even in the absence of supporting road infrastructure (a relatively rare condition in China), with a maximum potential score of up to 0.1.

In the process of cultural heritage development and preservation, greater attention should be given to identifying and preserving heritage sites that are located near existing major heritage sites. These sites should be strategically connected via road networks to form cultural corridors, so that heritage sites with higher CTA can enhance the visibility and influence of those with lower transmission ability. For heritage sites currently exhibiting low CTA, improving surrounding transportation infrastructure can enhance their connectivity and contribute to raising the overall CTA of cities.

Different categories of cultural heritage often exhibit varying levels of CTA. According to “The Standards, Registration Forms, and Documentation Guidelines of the Fourth National Cultural Relics Census”, heritage is classified into six major categories and 38 subcategories. The six major categories are: (1) architectural heritage, (2) archaeological sites, (3) burial sites, (4) modern and contemporary heritage Sites, (5) grotto temples and stone Carvings, and (6) others. The “others” category refers to heritage types that do not fall into the first five classifications, including mixed-type or special cases. In this study, all heritage sites classified under “others” are cultural landscapes, a subcategory within that category. Among these categories, architectural heritage, archaeological sites, burial sites, and modern and contemporary heritage sites are the most numerous, accounting for 56.2%, 19.5%, 10.6%, and 9.7% respectively. Their spatial distributions are illustrated in Fig. 15. The distribution of different categories of heritage varies significantly. Architectural heritage is mainly concentrated in Suzhou, Wuxi, and Yangzhou; archaeological sites are primarily found in Wuxi; burial sites are mainly located in Xuzhou; and modern and contemporary heritage sites are concentrated in Wuxi. These categories of heritage are not clustered in the same areas. This spatial pattern is closely related to the cultural differences between the northern and southern regions along the Jiangsu section of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal.

Based on the clustering analysis results, the top three categories of heritage consist of 22 sites, with median CTA scores above 0.2. In contrast, the median score for the fourth category is only 0.012. Therefore, the heritage in the top three categories has a stronger CTA and can be classified as high-transmission heritage. Among these high-transmission heritage sites, historical buildings account for the largest proportion, at 81.8%, followed by modern and contemporary important historical sites (all related to famous persons’ former residences), and the ‘Others’ category, which consists entirely of cultural landscapes, each representing 9.1%. The findings suggest that, in the study area, heritage sites with high CTA are predominantly architectural heritage, whereas burial sites and archaeological sites, despite their greater numbers, demonstrate relatively weaker CTA.

The cities along the Jiangsu section of theBeijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal exhibit distinct spatial patterns in the distribution of different categories of heritage. The concentration of archaeological sites, architectural heritage, burial sites, and modern and contemporary heritage sites differs significantly across cities. Therefore, when developing heritage resources, each city should focus on leveraging its locally dominant heritage categories to highlight unique cultural characteristics. Since different categories of heritage exhibit varying levels of CTA, efforts to enhance the influence of burial sites and archaeological sites should prioritize innovative communication strategies, such as the development of popular cultural IPs, in order to increase their visibility and attract broader public engagement.

The combination of heritage sites serves as an effective strategy to enhance CTA. Such approaches generally fall into two forms. The first involves low transmission ability heritage sites being paired with high transmission ability sites to form integrated scenic areas, thereby boosting the visibility and impact of the former, this approach is referred to in this study as “high supports low”. The second involves grouping multiple low transmission ability sites together to form a cohesive heritage destination, thereby collectively increasing their cultural influence, this is referred to as “low clusters into high”. This paper illustrates these two approaches with case studies of Huishan ancient town in Wuxi and Hubushan folk scenic area (Hubushan) in Xuzhou, respectively.

Huishan ancient town contains multiple heritage sites with varying levels of CTA. Based on the characteristics of these heritage sites, a network topology diagram was created using Python, as shown in Fig. 16. In the diagram, the size of each node represents the CTA of the corresponding heritage site, the larger the node, the stronger its transmission ability. The thickness of the connecting lines indicates the degree of association between heritage sites. A stronger connection is represented by a thicker line. As illustrated in the figure, Huishan Temple, Jichang Garden, and the Second Spring Under Heaven exhibit significantly higher CTA than the other sites. These three core sites are closely integrated with the overall Huishan ancient town scenic area and strongly interconnected with each other. The surrounding ancestral halls enhance their own CTA by establishing connections with these key heritage sites.

The Hubushan is primarily composed of heritage sites with relatively low individual CTA. Unlike Huishan ancient town, all the heritage sites in this scenic area fall under the category of architectural heritage, and are thematically unified by their focus on showcasing folk culture of Xuzhou across different historical periods. Although each heritage site has a limited influence on its own, their aggregation under a common cultural theme significantly enhances the overall CTA of the scenic area.

For heritage sites that are geographically proximate, integrating those with higher CTA to form heritage towns or tourist attractions is undoubtedly an effective strategy. In contrast, for regions where heritage sites generally exhibit lower CTA, consolidating multiple sites around a shared cultural theme, such as the evolution of local folk traditions, can still significantly enhance their collective CTA through the development of a unified folk-themed scenic area.

While previous research has primarily focused on the physical preservation of heritage and the influence of ecological, geographical, and social factors, there has been a lack of quantitative evaluations of CTA based on objective data. Despite the strengths of this study in addressing this gap, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, although social media data are more accessible and openly available than traditional evaluation data, they may be subject to artificial manipulation, such as bot-generated traffic or promotional activities, which could compromise the accuracy of the results. Second, this study does not account for the temporal dynamics of CTA, so the evaluation is based solely on static data from the year 2023. Future research should incorporate longitudinal data to explore how CTA evolves over time and responds to temporal and seasonal variations.

Overall, this study proposes a quantitative evaluation method for the CTA of heritage based on social media (Douyin, Weibo) data. It then analyzes the factors influencing the CTA of heritage from four aspects: data structure composition, transportation, spatial distribution, and heritage categories. The following results are obtained:

(1) The heritage along the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal in the Jiangsu section is generally concentrated, mainly in Suzhou, Wuxi, Yangzhou, Huaian, and Xuzhou. Among these, Suzhou, Wuxi, Yangzhou, and Huaian have stronger overall CTA for their heritage. Based on the research on the number of heritage sites in each city, it is found that the number of heritage sites directly reflects the cultural depth of a city, affects the overall CTA of a city.

(2) The overall CTA of a city relies on the combined support of three key components: the number of heritage sites, the most representative heritage site in the city, and those with mid-level scores. Enhancing the CTA of mid-level heritage sites is particularly effective in boosting the overall CTA of a city. An analysis of the data structure of CTA across cities reveals that the overall cultural transmission ability is positively correlated with the total number of heritage sites, the Maximum Heritage Score, and the Maximum Probability Score. Moreover, the CTA of individual heritage sites shows a negative exponential relationship with their ranking.

(3) In terms of spatial distribution and transportation factors, the study indicates that spatial clustering of heritage sites is more conducive to cultural transmission, while the spread of culture is also constrained by transportation conditions. Integrating geographically proximate or easily accessible heritage sites to develop cultural tourism zones can significantly enhance their CTA. Two common integration models are the “Huishan ancient town Model” and the “Hubushan Model.” The former boosts the communication of surrounding ancestral halls through the influence of renowned sites such as Huishan Temple, the Second Spring under Heaven, and Jichang Garden. The latter improves overall CTA by integrating culturally and geographically related heritage sites into the Hubushan.

(4) The heritage sites along the canal corridor exhibit a rich variety of categories. Influenced by multiple cultural zones, different categories of heritage demonstrate significant spatial distribution differences. Moreover, there are notable disparities in CTA among these categories. Architectural heritage demonstrates the strongest CTA, whereas archaeological sites and burial sites tend to have relatively weaker influence. In the future, innovative promotional approaches should be adopted to enhance the CTA of the latter two categories.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code used in this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Jin, Y., Zhang, Y. & Hou, B. Pathways and mechanisms of heritage tourism utilization of the Grand Canal from an evolutionary perspective: a case study of cities along the Jiangsu-Zhejiang section of the Grand Canal in China. Tour. J. 39, 53–70 (2024).

Sun, S., Zhang, L. & Zhu, X. Knowledge representation and semantic enhancement framework construction of linear heritage resources under the background of cultural big data (in Chinese). Mod. Inf. 43, 96–111 (2023).

Zhang, S. et al. Tourism value assessment of linear heritage: the case of the Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal in China. Curr. Issues Tour. 26, 47–69 (2023).

Li, Y. & Zheng, N. Integral protection of heritage of the Grand Canal of China: a perspective of cultural spaces. Sci. Technol. 2, 60–69 (2020).

Huang, W., Xi, M., Lu, S. & Taghizadeh, F. Rise and fall of the Grand Canal in the ancient Kaifeng City of China: role of the Grand Canal and water supply in urban and regional development. Water 13, 1932 (2021).

Fang, L., Cheng, X. & Yao, G. Research on the strategy of promoting the coordinated development of Grand Canal water transport and other transport modes, taking Jiangsu as an example. Sustainability 15, 15314 (2023).

Xu, C., Cao, L., Wang, J., Kong, F. & Wang, N. Coupling coordination relationship between ecosystem services and economic development in the Jiangsu section of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal and identification of contributing/ barrier factors (in Chinese). Acta Ecologica Sinica. 1, 1–17 (2015).

Zhang, Y. et al. Habitat quality assessment and ecological risks prediction: an analysis in the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal (Suzhou section). Water 14, 2602 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. On conservation of world heritage Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal for enhancing cultural ecosystem services. Herit. Sci. 11, 269 (2023).

Xu, Y., Hu, D., He, H., Zhang, Z. & Bian, D. Spatial and temporal evolution characteristics of the ecosystem service value along the Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal. Appl. Sci. 14, 8295 (2024).

Ge, H. & Liu, Y. Exploration and enlightenment of heritage distribution in the Jiangsu section of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal (in Chinese). J. Econ. Water Resour. 42, 72–78 (2024).

Yang, J. et al. Analysis of spatial and temporal distribution patterns of traditional opera culture along the Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal. Int. J. Geo Inf. 12, 477 (2023).

Li, L. Cultural communication and diversity along the Grand Canal of China: a case study of folk songs in intangible heritage. Herit. Sci. 11, 66 (2023).

Huang, Y. & Yang, S. Spatio-temporal evolution and distribution of heritage sites along the Suzhou canal of China. Herit. Sci. 11, 188 (2023).

Zhou, B., Meng, Y., Li, X. & Liu, S. Study on the spatial differentiation and influencing factors of settlement heritage in the cultural belt of the Grand CanalvJiangsu-Zhejiang section) (in Chinese).Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 33, 1942–1952 (2024).

Shi, G. et al. An analysis of the spatiotemporal distribution and influencing factors of national intangible heritage along the Grand Canal of China. Sustainability 16, 9138 (2024).

Zhang, S., Zhang, X. & Liu, J. Spatial distribution and pedigree age of intangible heritage along the Grand Canal of China. Herit. Sci. 12, 246 (2024).

Chen, M., Wang, J., Sun, J., Ye, F. & Zhang, H. Spatio-temporal distribution characteristics of intangible heritage and tourism response in the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal Basin in China. Sustainability 15, 10348 (2023).

Rong, Q. & Wang, J. Interpreting heritage canals from the perspective of historical events: a case study of the Hangzhou section of the Grand Canal, China. J. Asian Architect. Build. Eng. 20, 260–271 (2021).

Vidaurre-Rojas, P. et al. A social media adoption strategy for cultural dissemination in municipalities with tourist potential: Lamas, Peru, as a case study. Built Herit. 8, 12 (2024).

Liu, K. et al. Bibliometric and visual analysis of sustainable preservation of heritage gardens. Herit. Sci. 12, 355 (2024).

Shan, C. & Xi, Z. Historic urban landscape of Ming and Qing dynasties in Jiangsu section of the Grand Canal: taking Huaian as an example (in Chinese).Architect. Culture 2022, 192–194 (2022).

Zhang, H. & Hou, B. Research on the coordinated development of heritage tourism in the Jiangsu section of the Grand Canal from the perspective of spatial structure theory (in Chinese).J. Sichuan Tourism Univ 2020, 72–75 (2020).

Dong, T. Research On Digital Art Communication Of Chinese Elements In The Internet Era (in Chinese). (Southeast University, 2020).

Peng, N. et al. A vulnerability evaluation method of earthen sites based on entropy weight-TOPSIS and K-means clustering. Herit. Sci. 12, 161 (2024).

Yue, J., Yang, Q., Luo, Z., Chen, W. & Yue, M. Evaluation of surface weathering degree of brick historical buildings based on GLCM-entropy weight TOPSIS: a case study in the Kaifeng City Wall. Int. J. Architect. Heritage 2025, 1–18 (2025).

Wang, D., Wang, Y., Shen, X., Wan, J. & Cui, K. Quantitative assessment of the peeling on earthen heritage sites using an improved rank sum ratio. Int. J. Architect. Heritage 2024, 1–18 (2024).

Xu, S., Wang, J. & Peng, Z. Study on the promotional effect and mechanism of new quality productive forces on green development. Sustainability 16, 8818 (2024).

Zhu, Y., Tian, D. & Yan, F. Effectiveness of entropy weight method in decision-making. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 1–5 (2020).

Shannon, C. E. A mathematical theory of communication. Sigmob. Mob. Comput. Commun. Rev. 5, 3–55 (2001).

Luo, Y. & Li, Y. Comprehensive decision-making of transmission network planning based on entropy weight and grey relational analysis. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 37, 77–81 (2013).

Wen, Z. Structural Heterogeneity Evaluation Model Of Coal Reservoirs Based On Hierarchical Entropy Weight Method (in Chinese). (China University of Mining and Technology, 2023).

Hwang, C.-L. & Yoon, K. Methods for multiple attribute decision making. In Multiple Attribute Decision Making. Lecture Notes in Economics and Mathematical Systems, 186 (Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 1981).

Zhang, L., Wang, Y., Zhang, J., Zhang, S. & Guo, Q. Rockfall hazard assessment of the slope of Mogao Grottoes, China based on AHP, F-AHP and AHP-TOPSIS. Environ. Earth Sci. 81, 337 (2022).

Eshimiakhe, D., Jimoh, R., Suleiman, M. & Lawal, K. Improved cluster analysis of Werner solutions for geologic depth estimation using unsupervised machine learning. Kuwait J. Sci. 51, 100144 (2024).

Macqueen, J. Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. Proc. Fifth Berkeley Symp. Math. Stat. Probab. 1, 281–297 (1967).

Yang, J. & Zhao, C. Survey on K-means clustering algorithm. Comput. Eng. Appl. 55, 7–14 (2019).

Okabe, A., Satoh, T. & Sugihara, K. A kernel density estimation method for networks, its computational method and a GIS‐based tool. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 23, 7–32 (2009).

Fu, J. & Mao, H. Study on the spatiotemporal distribution patterns and influencing factors of heritage: a case study of Fujian Province. Herit. Sci. 12, 324 (2024).

Thompson, A. E. et al. Ancient Lowland Maya neighborhoods: average nearest neighbor analysis and kernel density models, environments, and urban scale. Plos One 17, e0275916 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the anonymous reviewers for their invaluable comments and suggestions on this manuscript. This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51808246) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2019YFC1520500). We thank the editors and reviewers for their constructive feedback, and we are also grateful to all the open-access platforms that provided data for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.P.: conceptualization, methodology, resources, writing—original draft, supervision, funding acquisition; Y.C.: methodology, validation, investigation, writing—original draft; L.W.: formal analysis, data curation, resources; C.Z.: software, writing—review and editing, visualization; Y.Z.: validation, writing—review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, N., Chen, Y., Wang, L. et al. Cultural transmission ability of urban heritage along the Jiangsu section of the Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 401 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01979-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01979-2