Abstract

Poetic texts are crucial for uncovering heritage sites’ cultural values. This research uses natural language processing (NLP), Python-based co-occurrence semantic networks, and kernel density analysis to study 2065 ancient poems on Hangzhou’s West Lake, exploring landscape imagery and sightseeing behaviors. It identifies four typical landscape images with specific elements, structural characteristics, and significant spatial differentiation, influenced by natural foundations, socio-economic contexts, and ideologies, which shape diverse tourism motivations and tourism behaviors. Based on these insights, it proposes conservation and utilization strategies at individual sites, tourist routes, and regional levels to enhance preservation and sustainable use, aiding in restoring original imagery, preserving authenticity, and providing valuable insights for heritage management amid modern tourism demands.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cultural heritage, as a unique type of heritage that embodies historical information, artistic achievements, and social values1, is not merely a physical space, but also a cultural space and spiritual space. Its core value lies in its role in cultural expression within specific temporal and spatial contexts2 as well as in spiritual transmission3,4. However, cultural heritage sites generally confront multiple intertwined practical dilemmas, forming systemic challenges, among which the most prevalent is the imbalance between protection and utilization. Many heritage sites have overdeveloped commercial facilities, with uniform antique blocks and internet-famous check-in spots damaging their historical spatial atmosphere, leading to homogeneous scenic landscapes and loss of cultural elements—common discordant phenomena in cultural heritage tourism. Tourism overload constitutes another global challenge confronting the development of heritages, including European cities like Turin and Lyon5, the Greek island of Cyprus6, and the Eastern North Carolina Heritage Complex7. The excessive concentration of tourists imposes severe environmental pressure on popular attractions, thereby affecting the authenticity and integrity of heritage sites8,9. In the current era, social media exerts a bifurcated influence on this sector: it aids in the dissemination of culture, yet concurrently entrenches the public’s intrinsic perceptions of cultural heritage through singular tourism recommendations. This entrenchment constrains the public’s capacity for profound engagement with cultural heritage landscapes, thereby intensifying spatial imbalances in tourism10. Therefore, fully exploring the authentic relationship between visitors and the environment in heritage sites, delving into the multiple layers of cultural landscapes in heritage sites, and preserving the cultural uniqueness of heritage sites will help safeguard the diversity and authenticity of heritage sites and form a more balanced and rational pattern of heritage protection and development.

Because of the historical attributes of heritage sites, historical materials are an important source for uncovering their cultural value11. In regional literature, heritage landscapes serve as the context where the subject and object of literature converge12. It not only incorporates descriptions of spatial and geographical structures, but also the recorded folk customs and sightseeing activities, delineate the general contours of the local humanistic landscape, indirectly reflecting the interconnections between landscapes, social structures, and ideologies. By extracting the landscape system from literary elaborations, the internal logic underlying the local humanistic landscape pattern can be discerned, which in turn enhances the understanding of such a pattern. Studies worldwide have validated the effectiveness of landscape research in regional literature. For instance, Gert Jan van Wijngaarden analyzed landscape elements in Homer’s epics to investigate the ancient Ionian Islands13, Mohd Amirul Hussain et al. compiled Malay heritage landscape elements from literary manuscripts14, and Claudia Heindorf et al. examined landscape changes in German peatlands through poetry15. Notably, landscape spaces in literary works possess both objectivity and subjectivity. Creators transform specific natural and human geographical spaces into artistically expressive imagery imbued with cultural meanings through collecting, selecting, perceiving, and integrating environmental information16. In this process, creators autonomously choose cognitive objects in poems based on personal emotions, projecting their life experiences and spiritual world onto them—merging physical and imagined spaces with the reader’s esthetic perception to form culturally vibrant landscapes. Literary “subjectivity” reflects distinct regional humanistic traits and the sociological significance of places/spaces, vital for studying geographical spaces and literary landscapes. Among regional landscape writings, poetry stands out. While sharing the subjectivity of other historical-literary texts, it is more concise, precise in meaning, salient in spatial elements, and intense in esthetic tone—making it a key medium for researching space, humanity, and landscapes. Advancements in text-mining techniques have enabled the exploration of intrinsic relationships and spatial distributions of landscape imagery within extensive poetic texts17, which complement traditional historical research. In China, ancient poetry constitutes a significant genre of regional literature, and the extensive preservation of poetic texts has underpinned research on regional landscapes in such places as Mount Lu16, the Tang Poetry Road in eastern Zhejiang11, and Buddhist temples of the Ming and Qing dynasties18.In such studies, researchers, drawing on the subjectivity of poetry, treat texts as products of creators’ landscape perceptions and regard landscape elements within them as poetic symbols constituting poetic landscapes19. Elementary landscape elements are extracted through word segmentation, cleaning, and standardization, and some sites of landscape perception are identified based on their occurrence frequency. After element extraction, constructing a co-occurrence semantic network and conducting cluster analysis yield groups of landscape elements with high correlation. Researchers have reached a consensus on the conceptual definition and analysis of these groups, generally referring to them as “landscape imagery”—a combination of poetic symbols with varying contents that both reflect the structural characteristics of landscapes and align with the subjectivity and personal esthetics of poetic texts19.

With the introduction of geographic information technology, extracting geographic information from poetic texts has become a fundamental approach to studying the spatial distribution of cultural heritage, reconstructing regional humanistic landscape patterns, and achieving spatial expression of regional humanistic environments. In such studies, researchers typically first identify locations in poetic texts, obtain their longitude and latitude, and then reveal the characteristics or laws of landscape spaces in poetry from various perspectives. Accurate georeferencing of poetic samples is critical. Spatial information in ancient poetry includes both regional landscapes directly observed by the author and associated spaces beyond the creation site, mostly presented as place names—serving as direct clues for geographic identification. However, due to inconsistencies in the granularity of spatial descriptions and discrepancies between ancient and contemporary toponyms, researchers mostly use methods like comparing ancient and modern place names, positional inference, and approximate substitution for spatial localization of poems19. Existing studies have examined the spatial characteristics of place-name landscapes, humanistic landscape patterns, and even local emotional expressions in poems. For example, Cooper analyzed the geographical representation of the Lake District through English poetry20, while Ludovic Moncla et al. examined the geographic distribution of Parisian street names in 19th-century French novels21. Li and Xu constructed the spatial imagery of natural and humanistic landscapes, identified key regions, and proposed strategies for the urban agglomerations along the Tang Poetry Road in eastern Zhejiang17,22. It is evident that ancient poetry constitutes a crucial source of data for exploring the value of cultural landscapes. From the perspective of human-land relationships, excavating landscape information embedded in poetry to supplement or further refine the existing value system holds significant implications for constructing the tourism esthetics of cultural heritage sites.

Beyond extracting landscape information from tourism poetry, the behavioral activities of humans—as the primary subjects of tourism—are equally worthy of attention. Tourism behavior is grounded in landscape space, which offers the physical framework and environmental context for tourism experiences23. Different landscape features influence the development of distinct tourism motivations and behaviors24. In heritage site tourism, visitors’ behaviors embody their ways of engaging with and interpreting heritage spaces. Research into tourism behaviors within heritage spaces reveals visitor-landscape interactions, identifies preferences, esthetics, needs, and expectations25, clarifies traditional visiting patterns, and aids in optimizing tourism products and services26. While landscape studies using regional literary texts have matured in extracting heritage site spatial and geographical information, they generally neglect depicted visitors’ behavior, with only limited research touching on visiting traditions. Yang Weihao’s analysis of 260 Tang poems on temple visits in Chang’an found strong regional characteristics in landscape imagery, significantly correlated with recreational activities and routes—confirming that tourism behaviors in ancient poetry, as a direct expression of human-land relationships, merits attention and in-depth study27. Thus, beyond extracting landscape imagery from regional literature, exploring tourism behaviors within these landscapes and their correlations will help create tourist spaces aligned with esthetic preferences, guide destination choices scientifically, and foster balanced heritage protection and development.

Hangzhou’s West Lake, located in the heart of Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, was inscribed on the World Heritage List in 2011. Despite its global recognition as a popular tourist destination, the West Lake faces challenges related to spatial imbalance in tourism development. The widespread promotion of the “Ten Views of West Lake” has reinforced tourists’ perceptions, resulting in significant overcrowding in certain areas. With modern urban development and changes in visitor demographics, the traditional “Ten Views of West Lake” struggle to accommodate the influx of tourists, leading to overcrowding. To improve tourism quality, it is essential to explore and promote more diverse landscape images beyond these traditional scenes. West Lake’s extensive regional literary heritage, accumulated over centuries, offers a wealth of descriptions of both landscape spaces and sightseeing behaviors. Given its rich literary heritage and evolving tourism dynamics, West Lake thus serves as an ideal subject for exploring the interplay between landscape imagery and tourism behaviors. Utilizing digital and geographic information technologies, this research extracts landscape elements and tourism behaviors from ancient poetry to reveal the structural and spatial characteristics of West Lake’s traditional poetic landscapes. It further explores the authentic human-landscape relationship, investigates the drivers and mechanisms of this interaction, and proposes adaptive strategies for modern heritage tourism. This approach aims to enhance West Lake’s tourism adaptability and serve as a reference for the sustainable development of similar cultural heritage sites.

Methods

Research area and profile

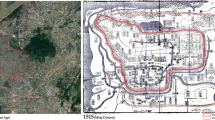

The Hangzhou West Lake Scenic Area is located in the central urban area of Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, covering a total area of 59.64 km² (Fig. 1). In 2011, it was officially inscribed on the World Heritage List. West Lake is bordered by mountains on three sides and adjoins the city on the fourth. Its surface is segmented by causeways and islands, forming the iconic landscape pattern known as “two causeways and three islands.” Originally, West Lake was a lagoon at the estuary of the Qiantang River ~2000 years ago. Sediment accumulation eventually separated it from the sea, forming a freshwater lake. Before the Tang Dynasty, the lake primarily served agricultural irrigation, urban water supply, and flood control functions. During the Tang Dynasty, the construction of the Bai Causeway divided the lake into the Outer Lake and Inner Lake, connecting Solitary Hill and North Hill. By the mid-to-late Tang period, Buddhist temples and pavilions began to appear around the lake, and activities such as springtime outings and boating became increasingly popular among residents.

Source: Base maps are sourced from standard maps (http://bzdt.ch.mnr.gov.cn/index.html). Research area—Hangzhou West Lake.

In the Song Dynasty, when the Southern Song established its capital in Lin’an (present-day Hangzhou), the city became a national hub of politics, economy, and culture. Under the governance of Su Dongpo, significant dredging projects were undertaken. The excavated silt was used to build embankments, quickly linking the northern and southern shores of the lake, thereby establishing the fundamental structure of West Lake’s landscape. West Lake’s recreational use expanded from the refined pursuits of scholars to a widespread public phenomenon, setting a precedent for urban tourism in ancient China. The official local chronicles of Hangzhou, such as Hangzhou City Chronicles28 and Complete Book of West Lake29, provide detailed records of the lake’s scenic and historical development. Despite numerous renovations post-Song Dynasty, resulting in changes to its surface area and the addition of hydraulic infrastructure, the iconic landscape pattern of “two causeways and three islands” has been consistently preserved.

Data source

The scholarly examination of West Lake’s landscape management can be traced back to Liu Daozhen’s “Record of Qiantang” from AD 436. However, poetic compositions from the Tang Dynasty and earlier are mostly isolated cases, with few authors and poems, making it difficult to comprehensively reflect the characteristics of West Lake excursions during that period. During the Southern Song Dynasty, West Lake in Hangzhou became a prominent scenic site, inspiring a wealth of literary works focused on its history and landscape, and the writings of different groups, such as royal painters, scholars and officials, monks and the common people, jointly shaped the diverse images of West Lake, which were widely spread. These writings transformed abstract names into tangible cultural symbols. During this period, the “Ten Views of West Lake” were formed and widely spread through poetry and paintings10, becoming the representatives of the natural landscapes of West Lake. With the exception of the imperial southern inspections during the Qing Dynasty, visits to West Lake were traditionally spontaneous activities carried out by the general public until the Republic of China, when tourism companies emerged, turning these excursions into commercialized forms of modern leisure tourism. This research examines the spontaneous interactions between humans and landscapes, utilizing ancient poems about West Lake from the Song Dynasty through the end of the Qing Dynasty (960–1911) as the primary sources for this study. The “West Lake Literature Collection”, edited by the Hangzhou government, comprises 29 poetry collections from the Song to the Qing Dynasties, all centered on West Lake and possessing significant literary and historical value. From these collections, this study has selected 2065 poems specifically related to the theme of touring West Lake, with a cumulative total of 169,090 characters.

Research methods

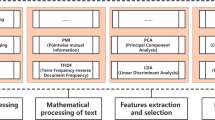

This research presents a research framework, as shown in Fig. 2, consisting of the following steps: (1) Using poetry texts as a primary data source, landscape elements that constitute poetic imagery are extracted through natural language processing (NLP) techniques to reveal the overall composition of poetic landscape symbols in West Lake. (2) Employing Python-based co-occurrence semantic network analysis, clusters of single-character landscape elements are identified to uncover the associative relationships among landscape elements in ancient West Lake poetry. This process yields several distinct types of poetic landscape imagery with significantly different content structures. (3) Kernel density analysis in GIS is then used to obtain the spatial distribution patterns of these representative landscape images and explore the driving forces behind their formation. (4) Elements of touristic behavior are extracted and coupled with the single-character landscape elements from typical poetic imagery to reconstruct a co-occurrence semantic network, thereby quantifying the relationship between tourism behaviors and landscape features. This step helps to uncover potential correlations among sightseeing motivation, tourist behavior, and landscape imagery. Based on the above results and the current state of tourism in West Lake, the study concludes by offering multi-dimensional recommendations for the future development and planning of the site.

This research uses the Python Jieba module for text segmentation and named entity recognition, with Collection and Posseg functions for word frequency statistics and morphological markup. Heterogeneous terms with the same semantics but different forms in the texts are standardized for quantitative analysis30. This paper defines two parameters, landscape elements and tourism behavior elements, which are used for the quantitative research of landscape imagery and tourism behavior, respectively.

Landscape elements mining. Drawing on Xu Tao’s approach of standardizing individual characters instead of entire words31, a set of words representing the landscape of West Lake was formed by eliminating meaningless words with fewer than two occurrences from the text of the poem, following semantic segmentation, word frequency analysis, and lexical annotation. Additionally, building upon the method of classifying landscape elements by Zhang Zheng32, Li Yuan18 and others. 256 words representing landscape elements extracted from West Lake poetry were classified into four categories: sky scenery, earth scenery, water scenery, and living scenery. The category of humanistic landscape resources includes two categories: structures and facilities, and characters, according to the short list of landscape resources classification.

Tourism behavior elements mining. After identifying the words that represent actions in the poems, we standardized these heterogeneous phrases into expressions that can denote specific tourism behaviors. Drawing on Wei Xiang-dong’s research33, and considering the motivations for touring and types of activities, we categorized the 184 tourism behavior elements extracted from West Lake poetry into five categories: scenic appreciation, cultural events, social gatherings, religious beliefs, and lakeside seclusion. These major categories were further subdivided into 23 subcategories based on activity types.

In order to verify the credibility of the aforementioned method, 50 elements with a word frequency >0.1% were selected as samples in this research to identify words in the original poems. The accuracy of element mining was assessed by comparing semantic relationships with the percentage of semantically compatible combinations. The results show that the West Lake poetry semantic mining method achieved an accuracy rate of 85.73% (Additional file 4), verifying the method’s effectiveness and accuracy in this research.

The Fast-Newman algorithm was utilized to calculate the co-occurrence relationships between the various elements. Standardized single-character landscape elements are grouped by association strength, yielding their clustering results—i.e., landscape imagery themes with distinct content and structural differences. Subsequently, based on these clustering results, standardized single-character behavior elements are visualized in secondary co-occurrence with them, and the visiting behavior characteristics associated with each landscape imagery are obtained. After constructing a 256 × 256 undirected multi-valued co-occurrence matrix and importing it into Gephi 0.9.7 software, we utilized the modularity operation, average weighting degree calculation, and filtering function in the community detection algorithm to cluster nodes according to their natural connectivity structure in the network. This process resulted in the construction of a co-occurrence semantic network, with elements as nodes and co-occurrence relations as edges. The Fast-Newman algorithm was employed to calculate the modularity (Q-value) to evaluate the quality of clustering; the larger the modularity, the better the clustering effect34. Equation (1) is as follows:

Let \(n\) represent the number of nodes in the complex network, and let \(m\) denote the number of edges connecting these nodes. For any two nodes \(v\) and \({w}\) in the network, \({A}_{{vw}}\) = 1 if there is an edge between them, and \({A}_{{vw}}\) = 0 otherwise. \({C}_{v}\) represents the community to which node \(v\) belongs, while \({K}_{v}\) and \({K}_{w}\) denote the degrees of nodes \(v\) and \({w}\) respectively. The function\(\,\delta ({C}_{v},{C}_{w})\) determines whether nodes \(v\) and \({w}\) are in the same community; \(\delta ({C}_{v},{C}_{w})\)=1 if they are in the same community, and 0 otherwise. The range of the value is [−0.5,1), when the value is between 0.3 and 0.7, it indicates a better clustering effect.

In this research, several major landscape scenes were identified by constructing a co-occurrence semantic network of landscape elements. Subsequently, these landscape elements were combined with tourism behavior elements to build another co-occurrence semantic network. The co-occurrence relationships served as parameters to quantify the connections between landscape elements and tourism behavior. Ultimately, four main tourism scenes were identified, leading to the construction of a landscape spatial-tourism behavior heat map.

The Force Atlas 2 algorithm is utilized to present the relationships between various types of elements. This force-directed algorithm is widely used in the visualization of complex networks. Its core principle is to simulate physical forces, allowing nodes to reach an energy-minimizing state in the graph. The algorithm performs well in large-scale networks and effectively demonstrates both the global and local structures of the network. The repulsive forces between nodes follow Coulomb’s law, which is represented by Eq. (2):

\({F}_{{\rm{r}}{\rm{e}}{\rm{p}}}(i,j)\) is the repulsive force between the node \(i\) and \(j\). \(k\) is a constant used to adjust the strength of the repulsive force, and \({p}_{i}\) and \({p}_{j}\) are the position vectors of nodes and respectively.

The gravitational force on the edges follows Hooke’s law with Eq. (3):

\({F}_{{\rm{a}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{t}}}(i,j)\) is the gravitational force connecting \(i\) the edges between the nodes \({i}\) and \({j}\).\({||}{p}_{i}-{p}_{j}{||}\) is the distance between the nodes\(\,i\) and\(\,j\).

Terms that can be labeled as attractions were extracted from 2065 poems using the Python jieba module to generate a list of attractions. The Python Requests module was utilized to call the Baidu Maps API for filtering and locating these attractions, with only those meeting two criteria retained: first, being mentioned in both the body and title of the poems; second, having locations precisely definable by modern latitude and longitude coordinates. This ensures that the selected attractions were not only described in ancient poems but also lie within the actual West Lake scenic area and have a long-standing visiting tradition. A geographic information data set of typical landscape spaces was constructed based on the screening of these attractions.

Subsequently, each attraction was associated with standardized landscape element words. Through the construction of a co-occurrence semantic network, the landscape element words with the highest degree of association with each attraction were extracted. In instances where multiple landscape words exhibited similar association strengths with an attraction, the landscape imagery associated with these words was verified, the association degree between each landscape imagery and the attraction was quantified, and the attraction was categorized into the landscape imagery category with the highest association degree. Equation (4) is as follows:

In the equation, K is the kernel function;\(\,{(x-{x}_{i})}^{2}\) + \({(y-{y}_{i})}^{2}\) is the square of the Euclidean distance from point (\({x}_{i}\), \({y}_{i}\)) to point (\(x\), \(y\)); r is the kernel density bandwidth, i.e. the search radius; n is the number of sample points within the radius. The search radius significantly impacts the analysis results: a smaller radius is suitable for reflecting local aggregation characteristics, while a larger radius is suitable for reflecting global-scale aggregation areas. Given that the scale of West Lake is smaller, a smaller radius was pre-selected to explore the landscape space and tourism behavior aggregation characteristics described in the poetry of West Lake.

Results

Extraction of landscape imagery of the West Lake

Poetic landscape elements are the basic symbols constituting poetic landscape spaces, and the frequency of their occurrence indicates the intensity of tourists’ perceptions. From the poems, 256 landscape elements were extracted and subsequently categorized into 2 primary categories, 7 secondary categories, and 53 subcategories. The analysis reveals that natural landscape elements are mentioned more frequently (7662 times) than cultural ones (4062 times), with 29 subcategories for natural landscapes and 24 for cultural landscapes. In the categories of natural landscape elements, Water Scenery, which includes lakes, constitutes the primary perceptual element for visitors when creating works after visiting the West Lake in Hangzhou, with the total frequency of this category reaching 2260 instances. Among these, large-scale water features, such as lakes (1318 times) and water (425 times), have the highest representation. Smaller-scale water features, like springs (175 times) and streams (123 times), also attract considerable attention from visitors. Pools (20 times) and islets (14 times) have lower frequencies, yet they confirm the diversity of water scenery types. Notably, the appearances of unconventional West Lake water elements, such as sea (24 times), river (65 times), and tide (48 times), suggest that visitors use imaginative expressions to expand the spatial scale of the lake, imbuing it with the dynamism of rivers and the vastness of oceans.

Sky scenery ranks second in sensory intensity, with a total frequency of 2596 instances. Sun, moon, and stars (790 times), cloud and mist landscapes (521 times), weather changes like wind, rain, and varying skies (500 times), and season changes (420 times) are frequently noted. At the subcategory level, the moon (492 times) is the most commonly described celestial phenomenon, while spring (303) is mentioned about three times more frequently than autumn (117 times). The high frequency of moon and spring references highlights visitors’ keen perception of West Lake’s daily and seasonal transitions. Wind and cloud also appear frequently, indicating that these dynamic landscape elements are among the most important sensory experiences for visitors.

Living scenery ranks third in sensory intensity among natural landscape sources, with a total frequency of 1722 instances, encompassing plant and animal landscapes. BLOSM dominates the plant landscape elements, reflecting the high ornamental value of West Lake’s plant scenery. Bamboo and willow are the most prominently perceived plant species by visitors. In the animal landscape, birds are the most significant sensory element, followed by beasts and fish, reflecting the ecological vitality of West Lake’s ancient forests and ponds. For example, Lin Bu’s poem “The crane leisurely lingers by the water”(鹤闲临水久) resonates with bird imagery.

In the secondary category of earth scenery, mountain views are the most deeply perceived by visitors. Subcategories such as mountain, rock, cave, and peak show high frequencies, with visitors precisely depicting the low hills on both sides of West Lake, characterized by numerous deep caves and rugged rocks. For example, Zhang Dai’s description “deep and unfathomable” (幽深不可测) portrays cave imagery.

In summary, visitors perceive water scenery most intensely, while the ever-changing sky scenery contrasts sharply with the unchanging water scenery, together constructing the celestial and terrestrial framework of West Lake’s poetic space, laying the foundation for its magnificent natural backdrop. The vibrant living scenery and extraordinary earth scenery serve as micro-perceptual objects, complementing and enhancing the water features in literary narratives, ultimately crystallizing into a “poetic and picturesque” esthetic paradigm of landscape.

In the secondary categories of cultural landscape elements, structures and facilities emerge as the most prominent, with a frequency of 2773 occurrences. These encompass a diverse array of scales and functions, including large-scale public service facilities such as palaces, residences, and temples, alongside smaller scenic constructions like pavilions, kiosks, and tombs. Infrastructure, such as roads and slopes, also constitutes areas with a relatively high degree of tourist perception. It is noteworthy that architectural details, such as curtains, frequently appear within the narrative of poetic spaces, suggesting that these functional buildings serve not only their practical purposes but also as objects of esthetic appreciation, interacting with the natural landscape and integrating into the comprehensive composition of West Lake.

Characters within the poetic landscape narrative constitute the active agents of West Lake’s poetic space. This category includes both the creators’ own tourism accounts and observations, with a dynamic interchange between the roles of observer and observed. The subcategories comprise nobles, scholars, and commoners, with officials and merchants establishing private gardens around Hangzhou’s West Lake, while ordinary people engage in trade at lakeside markets. This duality highlights the simultaneous occurrence of private garden appreciation and public folk activities. Moreover, mythical figures such as Buddha and immortals appear in poetic narratives, enhancing the mystical allure of West Lake’s cultural beauty.

The category of Historical Allusions reflects the historical stratification in the construction of West Lake landscapes and constitutes the non-physical component of the poetic space, which, together with visually perceptible landscape elements, forms the poetic space. The frequent occurrence of scholars indicates their significant participation in the construction of the West Lake landscapes. For instance, scholars like Bai Juyi and Su Shi, who served as government officials in Hangzhou, participated in West Lake governance projects and promoted West Lake landscapes through their poems and prose. The presence of monarchs, princes, famous ministers, and generals embodies the complexity of the construction process of West Lake cultural landscapes at the political and cultural level, as well as their educational and governance functions. Meanwhile, the emergence of myths, religious allusions, hermits, and virtuous figures in the poetic space demonstrates the cultural attributes of traditional West Lake esthetics and enhances the depth and hierarchy of landscape images.

It can thus be concluded that within the poetic narrative of West Lake, visible and tangible humanistic landscape sources—including constructed facilities and character roles—interact harmoniously with natural landscapes. This interaction superimposes humanistic beauty upon natural beauty, embodying the characteristics of “universality,” “omnitemporality,” and “omnidirectionality” in West Lake’s appreciation. Furthermore, invisible and intangible cultural landscape sources such as myths and legends, literati celebrities, and religious allusions have endowed West Lake’s landscapes with educational implications, permeating them with cultural thoughts beyond visual esthetics. Collectively, these elements constitute both the tangible and intangible components of West Lake’s poetic space, thereby expanding the perceptual dimensions of West Lake’s poetic esthetics (Fig. 3).

The poetic landscape imagery consists of highly correlated landscape symbols with structural hierarchies and networks. Using Python’s co-occurrence semantic network and Gephi, 256 standardized single-character landscape elements were clustered, resulting in four cluster subgroups centered around imagery perception object words with different core nodes. In the poetic space described in the poetic texts, these poetic symbols form four typical West Lake landscape images, condensing into esthetic themes in the poetic space and exhibiting significantly different structural characteristics. The modularity analysis yielded a \(Q\) value of 0.51, falling within the range of 0.3–0.7, indicating a significant level of clustering quality.

The analysis of landscape elements in Cluster 1 (Fig. 4) shows that natural landscapes account for the largest proportion (49.13%), primarily featuring trees like willows and peach blossoms, a variety of herbaceous flowers, and fauna such as insects, birds, and animals. This is followed by built facilities (32.85%), including transportation structures like roads, bridges, and ports, as well as smaller structures like tombs. This Cluster indicates that elements such as “flower,” “causeway,” and “cloud” have the highest node degrees, highlighting their importance in this cluster. Elements like “willow,” “peach,” “fish,” and “bridge” are particularly representative of the visitors’ perceptions. The spring scenery, epitomized by red peach blossoms and green willows combined with roads, bridges, and ports, creates a picturesque landscape for tourists. For instance, Dong Zigao’s Song Dynasty poem captures the essence of spring at West Lake through the alternating planting of peach blossoms and willows along Su Causeway, reflecting the visitors’ appreciation of nature’s seasonality. (“最是春来犹可玩, 桃花千树柳千株。”). In ancient times, West Lake tours primarily relied on walking, making the landscape along the routes a significant aspect of the visitors’ experiences. Consequently, transportation facilities like roads, bridges, and ports became key subjects in their perception. Overall, the landscape space of this cluster is characterized by a vibrant natural environment interspersed with small, elegant man-made structures, forming a typical landscape space that is dominated by dynamic natural excursions (Table 1).

The analysis of landscape elements in Cluster 2 (Fig. 4) reveals that large-volume structures, including pavilions, tombs of celebrities, ancestral halls, and former residences, constitute the largest proportion (38.65%). Windows and doors offer perspectives on how individuals view the landscape from these structures. Water features, making up 3.78% of the cluster, encompass streams and expansive lake and ocean surfaces. Elements such as “road” and “city” highlight the strong connection between West Lake and the urban landscape through a well-developed road system. Figure 4 shows that elements like “Flow,” “Lake,” “Window,” and “Town” have the highest node degrees, underscoring their prominence in visitors’ perceptions. Characters, comprising 11.66% of the cluster, primarily represent common people, with “Lady” indicating that women were a significant demographic among West Lake tourists (Table 2).

During the Ming Dynasty, public tours concentrated between Bai Causeway and Su Causeway became so popular that Yuan Hongdao noted in his Record of the West Lake, “The songs filled the air like wind, and powdered faces shimmered like rain. Elegantly dressed people outnumbered the grass along the causeway, creating a scene of striking beauty.” (“歌吹为风, 粉汗为雨, 罗纨之盛多于堤畔之草, 冶艳极矣。”)This reflects the trend of popularization and secularization in ancient West Lake tourism, as excursions became part of ordinary people’s lives, not just for the literati and aristocrats. Overall, Cluster 2’s landscape space is defined by the vast, misty waters of West Lake as its natural base, contrasting with Cluster 1’s intimate bridges and streams. Prominent structures interspersed with depictions of common people create a landscape imagery that integrates the natural aquatic environment within the urban space.

The analysis of landscape elements in Cluster 3 (Fig. 4) reveals that built facilities, particularly religious structures such as temples and Buddhist temples, constitute the largest proportion (42.20%). This is followed by ground scenery (28.98%), dominated by striking peaks and mountain landscapes. Elements such as “temple,” “monk,” “pavilion,” and “mountain” exhibit the highest node degrees, highlighting their significance in visitors’ perceptions. The scene prominently features natural elements like “mountain,” “spring,” and “cave,” alongside built elements such as “pavilion,” “temple,” and “pine,” with temples and courtyards serving as focal points (Table 3).

In this cluster, characters (10.67%) are predominantly monks, contrasting with Cluster 2, where commoners were more prevalent. The diminished prominence of “road” suggests that monks, rather than commoners, were instrumental in developing the mountainous landscape of West Lake. Historically, temples were not only religious sites but also served as resting places for tourists. For example, at Lingyin Temple, gatherings are described in verses like “monks feast full of garden sunflower, with the cloud dispersal of the quiet step.” (“僧筵饱园葵, 随云散幽步。”) Monks and people often toured together, composing poetry and exchanging philosophical ideas, transforming West Lake into a spiritual paradise where Buddhism and Taoism flourished. Overall, Cluster 3 integrates religious and mountainous landscapes, as depicted in verses such as “The clouds on the ridge rise up heavily, and the fairy pavilion reflects the Buddha’s palace in a variety of ways” (“岭头云气起重重, 仙馆参差映佛宫” “绿树层层怪石重, 东西涧绕梵王宫”). These verses portray a serene landscape with lush trees, unusual rocks, and streams encircling the temple.

The analysis of landscape resource elements in Cluster 4 (Fig. 4) reveals that sky scenery elements dominate, comprising 70.99% of the cluster. The largest subcategories within this are “rain and shine” and seasonal changes. Following this, living scenery elements account for 18.77%, primarily featuring birds and yellow warblers. In Fig. 4, the single character “moon” is central, followed by “smoke” and “rain,” with strong connections to elements like “waves” and “mud” Overall, “moon,” “rain,” and “wind” have the highest node degrees, reflecting visitors’ interest in weather phenomena such as rain and snow, and their attention to the passage of time, including day–night transitions and seasonal changes (Table 4).

The prominence of elements like “rain” and “wind” indicates a poetic focus on weather conditions and their impact on the landscape and human experience. A verse exemplifying this is: “I was already half drunk when I left the goblet in my hand, and I talked earnestly by the Xiling Bridge. The moon and wind are sparkling in the waves, and the reunion will be a great success” (“手把离觞已半醺, 西泠桥畔话殷勤。波中风月粼粼起, 那便团圆作十分。”). This describes a farewell gathering by West Lake, with moonlight shimmering on the water. Unlike traditionally favorable tourism weather, elements such as rain, snow, wind, and moonlit nights. This focus differs from the traditional emphasis on favorable weather for tourism. Instead, conditions like rain, snow, strong winds, and moonlit nights—despite limited light and greater visiting difficulty—offer an unusual experience of West Lake’s scenery. These elements, like smoke and rain or moonlit nights, enrich the esthetic value of the landscape, offering visitors a unique visual and emotional experience.

Spatial characteristics of West Lake’s poetic landscape imagery

Based on the aforementioned research methods, this study extracted a total of 97 precisely locatable West Lake sites from poetic texts and constructed co-occurrence semantic networks with 256 landscape elements, respectively, to identify the landscape imagery associated with each site. Subsequently, kernel density analysis was employed to obtain the spatial regions associated with each landscape imagery, reflecting visitors’ perceptual preferences in different areas of the West Lake. Based on historical data, combined with actual site characteristics and site remains, the spatial correlation patterns of each landscape imagery were explored.

The landscape imagery of Cluster 1 is mainly characterized by vibrant natural landscapes and exquisite small-scale artificial facilities. Kernel density analysis reveals that the landscape imagery of Cluster 1 shows a strong correlation primarily with the western part of the West Lake’s water surface, particularly around the Su Causeway, Breeze-ruffled Lotus at Quyuan Garden, and Viewing Fish at Flower Pound. The low-lying topography and frequent silt accumulation in this area create a favorable environment for diverse plant growth. Historical water conservancy projects led to the formation of walkable embankments, resulting in a dense network of roads, with the Su Causeway and Yang Gong Causeway being notable examples (Fig. 5).

In ancient times, due to the city wall’s isolation, tourists often exited the city through the Yongjin Gate on the east bank of West Lake. This area, within a suitable walking distance, is situated where mountains meet water, offering a stark contrast to the vast lake near the city gate. As visitors moved westward, they entered mountainous and forested areas, making this region a popular spot for tourists to experience nature. Numerous attractions known for their natural beauty are located here. In spring, the area boasts the picturesque peach and willow landscapes at the Spring Dawn at Su Causeway, the first of the Ten Views of West Lake. In summer, the Lotus Leaves and Blossoms in the Breeze-ruffled Lotus at Quyuan Garden and the Viewing fish at the Flower Harbor are celebrated for their natural scenery. The flora and fauna landscapes are abundant, offering seasonal diversity. Visitors enjoy the landscape, plants, flowers, and birds, engaging in leisurely strolls and excursions.

The landscape imagery of Cluster 2 is mainly characterized by the vast, misty waters of West Lake, with grand artificial structures as the focal points. Kernel density analysis indicates that Cluster 2 is predominantly distributed along the north shore of West Lake, exhibiting high-density agglomeration (Fig. 5). This area includes public water conservancy projects and monumental landscapes such as the White Causeway, Su Causeway, Yu Qian Ancestral Hall, Yuefei’s Temple, and Lin Bu’s Tomb. The topography features low mountains and flat land adjacent to the city, corresponding to the present-day north shore of West Lake and the Solitary Hill area.

Historically, this area was the first destination upon leaving the ancient city gate of Hangzhou, prompting early artificial development and reflecting the public nature of West Lake as a tourist attraction closely linked to daily life. The high proportion of structures and facilities in Cluster 2 indicates a long history of development, with numerous buildings spanning a significant time period. Since Hangzhou became the capital of the Southern Song Dynasty, urban construction and commercial development reached new heights, extending to the shores of West Lake. As the poem noted, “Thirty miles of buildings and platforms in one color, I don’t know where to find the lonely mountain” (“屋宇连接, 不减城中, 有为诗云: ‘一色楼台三十里, 不知何处觅孤山。’”), underscoring the secularization of visits to West Lake. From the Qing Dynasty painting Scenes of West Lake, it can be observed that visitors from different social strata often shared the same spaces within the landscapes of West Lake. Horseback riders and sedan chair passengers appear alongside those carrying burdens or pulling carts within the same scene. Meanwhile, the tombs and ancestral halls of historical figures such as Yue Fei, Lin Hejing, and Su Xiaoxiao were situated here. This was likely due to the high accessibility of the location, which facilitated people’s visits for worship and mourning—a practice aimed at educating the public. Over time, these sites gradually became significant sites in the region.

The landscape imagery of Cluster 3 is mainly characterized by religious and mountainous landscapes. Kernel density analysis indicates that Cluster 3 is distributed throughout the area, encompassing the surrounding mountainous regions of West Lake (Fig. 5). There are two main centers where tourists’ perceptions are most concentrated: the area around Lingyin Temple to the west of West Lake, and the area of Ge Ridge and Solitary Hill along the north shore. This cluster also includes public water conservancy projects, monumental landscapes, and religious buildings such as Baopu Taoist Temple. Phoenix Hill on the south shore of West Lake also has a high density of such perceptions. The region is predominantly mountainous, with rolling hills and distinctive peaks and rocks.

Historically, ancient religious sites were often situated in secluded, serene locations, distant from crowds. The mountains surrounding West Lake, with their beautiful scenery and appropriate distance from the city, attracted Buddhist and Taoist religious establishments. Among the most influential are Lingyin Temple and Baopu Taoist Temple, established during the Eastern Jin Dynasty. These sites, representing the symbiosis between Buddhism and Taoism, continue to exist today as symbols of the spiritual landscape of West Lake. Lingyin Temple is strategically located near Feilai Peak, while Baopu Taoist Temple is situated in Ge Ridge, each forming distinct centers on the kernel density distribution map. Notably, the Ge Ridge area is also a primary perception site for Cluster 2, where religious, commemorative, and daily activities converge, reflecting the area’s multifunctionality.

The landscape imagery of Cluster 4 is mainly characterized by landscape elements associated with celestial phenomena such as “moon,” “rain,” and “wind.” Kernel density analysis reveals that Cluster 4 centers around the lake, primarily covering the dyke islands within the lake and the north shore of West Lake (Fig. 5). Notable landscapes in this area include the Cold Spring Pavilion, the Pavilion in the Heart of the Lake, and the Moon Rock Pavilion. The vast water surface is a defining feature of this region.

The tranquil lake surface acts as a canvas, accentuating the natural beauty of the sky and becoming a distinctive esthetic focus. The themes of “moon” and “snow” illustrate the ancients’ appreciation of West Lake’s diurnal and seasonal changes, offering an alternative to mainstream tourism by emphasizing tours during night and inclement weather. This approach avoids the crowds associated with daytime and sunny visits, fostering a more intimate and contemplative experience. Celestial phenomena such as the moon, night, rain, and snow are imbued with elegant or poignant esthetic qualities, fully explored and appreciated as tourism resources. This has led to the inclusion of sites like “Autumn Moon over Calm Lake” and “Three Pools Mirroring the Moon” among the Ten Views of West Lake, representing the unique landscape of the region.

Kernel density analysis of all the obtained typical landscape imagery reveals the overall characteristics of the poetic space of the ancient West Lake, from which the distribution pattern of ancient visitors to the West Lake can be discerned. For the convenience of ancient-modern comparison and in-depth discussion, this study also focuses on these scenic spots. It first systematically crawls a total of 55,768 pieces of user-generated content (UGC) from three tourism platforms: Ctrip, Mafengwo and Xiaohongshu, and obtains the spatial distribution characteristics of modern tourists through kernel density analysis (Fig. 6).

The results show that the spatial distribution of ancient tourists was more uniform, whereas modern tourists exhibit a higher degree of spatial agglomeration. From the Song to the Qing Dynasty, visitor distribution had two primary cores: the north shore of West Lake and Lingyin Temple, indicating a strong connection between Hangzhou and West Lake and the significance of religious activities in citizens’ lives. In contrast, modern tourists are highly concentrated around the north shore of West Lake, Su Causeway, Viewing Fish at Flower Harbor, and Leifeng Pagoda, demonstrating a pronounced imbalance in spatial distribution. The differences between some ancient and modern sites of tourist attention, to a certain extent, reflect the changing relationship between the visiting subjects and the landscape objects.

Tourism behaviors in poetic landscape imagery

A total of 199 single words related to excursion behavioral elements were extracted from the West Lake poetry texts, with a total of 3231 occurrences, which can be classified into 5 excursion motives and 26 activity types. From Fig. 7, it can be seen that, among them, landscape exploration (1078 times) is the most common excursion motive, including regular excursion activities such as Scenic Appreciation, Touring the lake, Hiking, and Mountain Climbing. In addition, Social Gatherings (804 times) with group entertainment such as composing poetry, banquets, and singing accounted for the highest percentage, indicating that group tours for social purposes were an important mode of excursion at West Lake in ancient times. The next is more elegant Cultural Events (627 times), such as reciting poetry, leaving an inscription, and tasting tea. Although the total frequency of Lakeside Seclusion (474 times) and Religious Activities (248 times) is relatively small, they still belong to the more mainstream types of tourism activities. Overall, the West Lake can carry a variety of tourist motives, and the rich landscape imagery and poetic spatial atmosphere can stimulate a variety of tourist activities.

By presenting the secondary co-occurrence relationship between tourist behaviors and landscape imagery, the tourist motivations and activity types with strong correlations within each landscape imagery can be obtained. Combined with the specific composition of its landscape elements, geographical distribution characteristics, site history and current tourism situation, the behavioral patterns of tourists in different landscape imagery can be further explored, potential propositions in modern scenic area construction can be identified, which provides references for the optimization of modern tourism products.

The landscape imagery of Cluster 1 is characterized by blossom and willow landscapes as well as small-scale landscape structures, primarily concentrated in the low-lying areas west of West Lake’s water surface. Statistical analysis of visiting motivations and behaviors indicates that this landscape space stimulates diverse visitor motivations and activities. In the semantic co-occurrence network, elements such as “blossom” “causeway” and “willow” exhibit the highest node degrees, strongly correlating with tourism behaviors (Fig. 8). The most frequent co-occurring pairs are “Causeway-Touring lake”, “Blossom-Carrying a pot”, and “Moss-Strolling” (Fig. 8), forming the quintessential excursion imagery within this landscape

a Co-occurrence semantic network of landscape spatial elements and tourism behavior elements; b heat map of the co-occurrence frequency of landscape spatial elements and tourism behavior elements; c–f co-occurrence semantic networks of tourism behavior (motivated by Scenic Appreciation, Social Gatherings, Cultural Events, and Lakeside Seclusion respectively) and landscape elements.

Scenic appreciation emerges as the predominant tourism behavior (46 pairs), encompassing activities such as climbing the mountain, wandering and listening to bells (Fig. 8). This is followed by cultural events (15 pairs) and social gatherings (16 pairs), which include tea brewing, dancing, music playing, and meeting (Fig. 8), highlighting both landscape appreciation and social–cultural engagements. Historical poems capture these scenes, depicting blossom viewing in spring and enjoying the lake by boat. Unique to Cluster 1 is the motivation of Lakeside Seclusion (Fig. 8), reflecting historical appreciation for this tranquil landscape, a sentiment echoed by the presence of numerous historical gardens west of the lake.

Geographically, Cluster 1 is situated at the junction of waterways west of West Lake, offering a flat and accessible terrain distinct from the eastern mountainous areas. The dense network of water and roads enhances its capacity to accommodate tourists, fostering spontaneous and varied tourist behaviors and activities, particularly appealing to the general public. Contemporary analysis reveals that the landscape structure remains largely unchanged, dominated by interconnected water networks, dikes, and roads. However, modern kernel density analysis indicates increased tourist density, driven by the popularity of the Su Causeway and the Flower Harbor. Modern transportation infrastructure now seamlessly connects these sites to the city’s main roads, facilitating tourist access via public transit. Social media further influences tourist behavior, often guiding visitors to complete popular itineraries within limited time frames, such as walking the Su Causeway and boating on West Lake, resulting in homogeneous experiences. To mitigate overcrowding, it is essential to enhance tourists’ understanding of West Lake’s Ten Views and offer diverse options for activities and locations, thereby enriching the visitor experience. Therefore, it can enrich tourists’ cognition of the Ten Views of West Lake, provide more options for visiting places and tourist behaviors, and thus alleviate the phenomenon of overcrowding in this area.

The landscape imagery of Cluster 2 is characterized by broad water surfaces and large-scale structures, primarily located along the north shore of West Lake. Statistical analysis shows that cultural events have become the predominant tourist behavior in this area, surpassing traditional landscape tourism. In the semantic co-occurrence network, elements such as “lake,” “water,” and “road” have the highest node degrees and strongest associations with tourism behavior (Fig. 9). The most frequent co-occurring pairs are the three most frequent co-occurrence pairs are “Lake—Lamenting the past”, “Gate—Reciting poetry”, and “Water-drawing spring water” (Fig. 9), highlighting the visitors’ focus on West Lake’s water scenery and nearby pavilions, shrines, and monuments.

a Co-occurrence semantic network of landscape spatial elements and tourism behavior elements; b heat map of the co-occurrence frequency of landscape spatial elements and tourism behavior elements; c–e co-occurrence semantic networks of tourism behavior (motivated by Scenic Appreciation, Social Gatherings and Cultural Events respectively) and landscape elements.

Cultural events are the most significant tourism behaviors (Fig. 9), including actions like “lamenting the past”, linked to landscape elements such as “buildings,” “gates,” and “shrines”. visitors visiting the north shore often followed the footsteps of their predecessors, visiting sites like Yue Wang Temple and Lin Bu’s tomb to honor the sages through poetry. Lines such as “the old man lamenting the past and singing of sunset” (“吊古诗翁咏夕曛。”) capture the scene of visitors reflecting on the past under the setting sun. The second most common activity is “scenic appreciation” (24 pairs), involving solitary activities like sitting, standing, and wandering, strongly connected with elements like “city,” “building,” and “window.” Unlike the relaxing activities in Cluster 1, visitors here often engage in solitary reflection with a nostalgic mood (Fig. 9). Additionally, social gatherings (18 pairs) involve activities like “meeting” associated with structures, such as “buildings,” “platforms,” and water features, reflecting the ancient custom of escorting friends to the city gate (Fig. 9).

Geographically, Cluster 2 is situated on the north shore of West Lake, closest to the city, offering strong accessibility and a higher degree of artificiality, thus integrating closely with urban life and serving as a vital space for public activities. Compared to the past, the area’s mountain landscapes and cultural relics, such as Yuefei’s Temple and Lin Bu’s Tomb, remain well-preserved. Additional historical sites and graves from the Republican period further enhance the area’s cultural and commemorative atmosphere. It also serves as a primary site for Cluster 3, focused on religious activities, creating a diverse landscape resource scene. With the city’s expansion and the disappearance of city gates, West Lake is now surrounded by urban development. Despite losing its ancient proximity advantage, the area remains a popular tourist destination due to its rich and varied landscape resources. The Lingering Snow on the Broken Bridge, one of the Ten Views of West Lake, serves as a key entry point from the eastern city and is linked to the famous White Snake myth, attracting large crowds during holidays. To alleviate congestion, it is crucial to enhance tourists’ understanding of the area’s landscape resources and efficiently guide them to nearby attractions like Solitary Hill and Ge Ridge.

The landscape imagery of Cluster 3 is characterized by mountain landscapes and religious buildings, widely distributed in the mountainous areas surrounding West Lake. Statistical analysis of visiting motivations and behaviors indicates that Cluster 3, supported by its mountains and forests, serves not only as a location for scenic appreciation but also as a primary site for religious activities, integrating cultural events and social gatherings. In the new co-occurrence semantic network, “Climbing stairs”, “Listening to Sutras”, and “Preaching” emerge as the most significant tourism behaviors. Elements such as “temple,” “mountain,” and “pavilion” have the highest node degrees and strongest correlations with tourist behavior (Fig. 10). The most frequent co-occurrence pairs are “Pavilion-Climbing stairs,” “Temple- Climbing stairs,” and “Temple- Drewing Spring Water,” representing quintessential excursion images in this landscape space.

a Co-occurrence semantic network of landscape spatial elements and tourism behavior elements; b heat map of the co-occurrence frequency of landscape spatial elements and tourism behavior elements; c–f co-occurrence semantic networks of tourism behavior (motivated by Scenic Appreciation, Social Gatherings, Cultural Events, and Religious Beliefs respectively) and landscape elements.

In terms of the co-occurrence relationship between various excursion motivations and landscape elements (Fig. 10), landscape exploration is the dominant visiting behavior (42 pairs), including activities like climbing, wandering, listening to bells, and roaming. Landscape elements such as “temple,” “ridge,” “bridge,” and “cave” present the most representative visiting images in this space. Cultural events (25 pairs) and social gatherings, including reading, writing poems, making tea, sending people to temples, and gathering, are also significant (Fig. 10). Compared to other clusters, the literati significance of tourism behaviors here is more pronounced, with a serene and solemn atmosphere reflecting the friendship between monks and laypeople and the harmony between literati and scholars.

Cluster 3 is unique in its religious significance (Fig. 10), where monks and laypeople seek spiritual transcendence by meditating and contemplating in ancient temples nestled in the mountains and forests. These sites include “temples” and “caves” providing spaces for spiritual pursuits. Lines such as “Occasionally, I go to talk about Zen from the monks’ temples and leisurely buy drunkenness at the head of the lake” (“偶从僧寺谈禅去, 闲向湖头贳醉回。”) capture the essence of monks and laypeople's tourism together, discussing religion and philosophy to express their spiritual quests.

Geographically, Cluster 3 covers nearly all the mountains around West Lake. Religious beliefs historically drove monks and Taoists into the mountains, spurring the development of landscape resources and pioneering the development of West Lake’s mountainous landscapes. Today, the areas around Lingyin Temple and Ge Ridge remain central to religious excursions such as Buddhism and Taoism, showing a concentrated trend of tourist visits. Modern tourists tend to seek the most renowned attractions for their visits, often choosing Lingyin Temple and Upper Tianzhu while overlooking Fajing Temple, which is also a significant religious site. To manage tourists’ flow effectively around West Lake, the area surrounding Lingyin Temple and Ge Ling in the northwest should focus on strategies to divert crowds and alleviate congestion. Conversely, the regions around Phoenix Mountain and Yuhuang Mountain in the southwest should enhance their appeal to attract more visitors, thereby reducing tourist density in other parts of West Lake.

The landscape imagery of Cluster 4 takes the lake surface and natural weather as the main landscape elements, and the distribution covers the north shore of the lake and the dyke island in the lake (Fig. 11); from the statistical results of visiting motivations and tourism behaviors, the landscape is the most important visiting motive in Cluster 4. In the new co-occurrence semantic network, “moon”, “rain” and “oriole” have the highest node degree, and the three pairs of co-occurring relationships with the highest frequency are “Moon-Touring the lake”, “Moon-Wandering” and “Moon-Climbing mountains”(Fig. 11), which show the visitors’ attention to the celestial phenomena such as rain, snow, clouds, and the moon, and thus derive the excursion activities such as canoeing on the lake and mountain climbing under the moon.

a Co-occurrence semantic network of landscape spatial elements and tourism behavior elements; b heat map of the co-occurrence frequency of landscape spatial elements and tourism behavior elements; c–e co-occurrence semantic networks of tourism behavior (motivated by Scenic Appreciation, Social Gatherings and Cultural Events respectively) and landscape elements.

As the most important motivation for scenic appreciation (Fig. 11), it mainly includes the behavior of visiting, such as “Watching clouds”, “Touring the lake” and other tourism behavior. Cultural events as the motive for the tourism behavior are mainly for the “Expressing melancholy”, “Reciting poetry”; smoke, moon, snow and other scenery is the object of their literary creation (Fig. 11). The activities motivated by social gatherings consisted of “Being accompanied”, and were associated with elements of the landscape such as rain and the moon (Fig. 11). It can be seen that either activity is centered around natural weather, and the unusual experience of visiting the city at night with the bright moon, rain, and snow is also attractive enough for tourists. With the development of the city’s economy, the richness of nightlife drives the West Lake night tours, large-scale boat cruises, and drinking and banqueting activities. “The best Xiling moonlight night tour, the beauty of the face and put orchid boat.” Sentences such as these depicted the women on a boat on the lake to enjoy the moon night tour scene. The Old Story of Wulin says: “The West Lake is the world’s scenic spot, and the four sequences are always suitable for the sunrise and dusk, the rain and the sunshine.” (“西湖天下景, 朝昏晴雨, 四序总宜。”)

It can be seen from the above that the Song Dynasty West Lake tour has broken through the traditional concept of the spring tour of the regular tour time, and the lake and mountain tour has become an important daily activity of city residents throughout the year. And today’s comparison, the landscape pattern of the West Lake within the lake is not a big change, and the lake area has long been surrounded by the expansion of the city, the city lights at night, the mountainous area around the lake has also carried out the brightening project, the natural phenomenon of the original nature of the sky is compressed. At present, the Detailed Plan of West Lake Scenic Spot of Hangzhou (2022–2035) has the planning and construction of the water tour route and facilities, and the night public cruise of West Lake has been operated from the official website. At present, on the basis of the improvement of the hardware facilities, it should be considered how to improve the quality of tourism in the nighttime hours and the special weather, so that the tourists can perceive the esthetic value of the West Lake on a more level.

Discussion

This research investigates the historical attributes of cultural heritage sites, focusing on landscape imagery and visitor authenticity as depicted in ancient literary works. By applying dialectical thinking to the relationship between landscape space and visiting behavior, a research framework was developed that incorporates landscape elements, imagery, and visiting behavior for correlation analysis. West Lake in Hangzhou, China, serves as the case study. The findings provide guidance for heritage space development, aiming to preserve the authenticity of landscape styles and establish a scientific approach to heritage protection.

Through textual mining and quantitative analysis of ancient poems about West Lake, this research identifies the poetic symbols that form the landscape imagery and highlights its structural characteristics. It demonstrates that regional literary works can reveal typical landscape imagery of heritage sites, showing common perceptions among ancient tourists. The results indicate that a single heritage site can present multiple distinct landscape imagery themes with spatial differentiation, emphasizing the decisive role of natural topography and landforms. On the west bank of West Lake, the low-lying terrain led to the construction of dams and planting of flora, making elements like springs and peach blossoms key tourist attractions. This aligns with Zoderer’s35 and Zhang’s36 research, which confirm that site conditions significantly influence tourist preferences. Additionally, the research finds that socio-economic contexts and ideological trends also shape landscape features. Despite both banks of West Lake being mountainous, the north bank is more prominent due to its historical urban integration, facilitated by proximity to city gates. This highlights that landscape formation is influenced by multiple factors, including urban development and local traditions. In landscape style decision-making, it is essential to consider changes in social context alongside natural foundations. Urban expansion and the removal of city gates have altered the relationship between the north bank and the city, removing distinctions between urban and rural areas. The challenge of maintaining the authenticity of ancient relics while adapting to new tourist demographics remains a critical area for further research.

By integrating landscape elements with tour behavior elements, this research demonstrates that tour motivations linked to different types of landscape images can vary37,38. Furthermore, even when driven by the same tour motivation, tourists may display different behaviors based on the interactive landscape elements available to them. This aligns with previous research on excursion preferences, such as Nikolaevich’s examination of tourist flows in Altay39 and Rusnak’s research on tourist destinations in European urban heritage40. However, what distinguishes this study is that it further explores the identities, motivations, and specific activities of visitors as depicted in ancient poems. For example, under the same motivation of engaging in cultural activities, such behaviors manifested as tea-brewing and casual conversations with social functions by the lakeside, while in mountainous areas, they were mainly solitary meditation and poetry creation. The reason for this lies in the high accessibility of the area near the Solitary Hill and the Ge Ridge on the west bank of the West Lake, which allowed ordinary people to reach easily, making the tourism behaviors more popular and secularized. In contrast, due to the inaccessibility of mountainous areas, visitors were mainly literati and officials with financial means, and their activities, such as practicing Buddhism and composing poems, required a certain cultural foundation.

We also found that as a cultural landscape, the West Lake was influenced by the social atmosphere of advocating culture and the trend of landscape esthetics, resulting in diverse motivations for visitors. Besides sightseeing, motivations such as participating in cultural and religious activities also played an important role, indicating that the conscious appreciation and utilization of its cultural value were an important part of traditional visits to the West Lake. In ancient times, visitors were mainly citizens living around the West Lake in Hangzhou. However, with the convenience of transportation, most modern visitors to the West Lake come from other places, mainly aiming to enjoy the scenery quickly in a short time. Therefore, the reasons for the differences in tourism behaviors are not only related to the attractiveness of the landscape space characteristics but also to the group characteristics of the visitors.

Exploring the landscape imagery in regional literature and the laws of tourism behaviors can provide references for the construction of heritage sites at multiple levels. Based on the above research results, this study attempts to discuss the protection and development of the West Lake cultural landscape from three aspects: scenic spot construction, tourist routes, and overall improvement, so as to safeguard the diversity and authenticity of the poetic landscape imagery of the heritage site and put forward strategies for its modern adaptation. Sites are the most basic units for identifying heritage sites, and some sites in scenic areas are the most direct manifestation of the imbalance in the tourism space of heritage sites. Measures can be considered to regulate some sites and activate cold spots. Modern visitors to the West Lake Scenic Area are highly concentrated in the lakeside area where the Ten Views of the West Lake are distributed. The three scenic spots of Su Causeway and the Viewing Fish at Flower Harbor, located to the west of the lake area, cover a relatively wide range, but modern visitors are overcrowded in the local areas. It is advisable to make full use of the interleaved water features and good ecology to build a rich road network, guide the dispersion of people flow, enhance the signage and esthetics of transportation facilities such as roads and bridges in the area, simultaneously optimize the landscape style around the gathering points, improve the tourist carrying capacity and service capacity, and reduce the density of local visitors. For the two scenic spots of Broken Bridge with Remnant Snow and the Autumn Moon over the Calm Lake, due to their being surrounded by water and limited development space, it is necessary to control the number of visitors at the road entrances and guide the flow of people to the north bank of the West Lake where the population density is lower. For the Evening Bell at Nanping Hill scenic spot on the south bank of the West Lake, efforts should be made to enhance its own attractiveness and link it with the historical relics in the nearby Phoenix Hill area to create a cultural-themed cluster south of the West Lake, so as to disperse the tourists from the Lingyin Temple area north of the West Lake. Cultural routes, by integrating similar cultural and natural heritage assets and emphasizing their contextual relationships, can offer visitors a comprehensive experience41and serve as a regulatory tool to mitigate tourism overexploitation42,43. Generally, different tourist groups have different motivations and esthetic preferences, so measures such as setting up thematic corridors and behavior guidance can be considered. Although there are spontaneously formed tour route guides among the people, no clear tour routes have been officially released. Based on the research results of the co-occurrence network of landscape imagery and tourism behaviors, as well as the differences between ancient and modern transportation, and considering the visiting motivations and esthetic orientations of modern tourists, thematic landscape tour routes can be designed. To the west of the lake, in the area around Yanggong Causeway and Wuguitan (Turtle Pond), a natural landscape-themed tour route can be designed, with “Taoliu Zanhua Path” (Path Adorned with Peach and Willow Blossoms) and “Hefeng Xunlu Line” (Line for Seeking Herons in Lotus Breeze) according to the four seasons, restoring the behavior pattern of “strolling along the causeway and carrying a pot of flowers”. With Beishan Street-Yuewangmiao (Yue Fei Temple) as the core scenic spot a humanistic narrative-themed tour route can be designed, integrating modern digital scene technology with constructed facilities to create an on-site reproduction of humanistic stories. Integrating the elements of “temple-cave-peak” in Lingyin-Geling, a religious mountain-themed tour route can be designed, with a “Zen Tea Trail” and organizing characteristic activities such as tasting tea at Cold Spring and listening to scriptures in caves. In addition, considering the needs of modern tourists for mountain climbing, fitness, and leisure, the comfort and accessibility of mountain trails can be enhanced44, and more spaces for staying and viewing can be added to guide tourists from the lakeside scenic area to shift to mountain tours.

For the entire West Lake scenic area, overall coordination and intelligent governance can be considered. After the Song Dynasty, the widespread dissemination of poems was one of the driving forces for the construction of the West Lake landscape. Literary works, as a “pre-structured framework”, have constructed an expectation space and esthetic tone for readers. Therefore, in the modern construction of the West Lake, we can fully integrate its temporal and spatial resources to comprehensively enhance the poetic atmosphere of the scenic area. According to the spatial differentiation of the four types of landscape imagery, we can consider strengthening and upgrading the poetic landscape imagery of different regions. In the west lake ecological zone, strengthen the landscape combination of natural scenery and small structures, set up ecological workshops, carry out plant rubbing and bird watching courses, and activate the visiting scene of “wandering along mossy paths”. In the mountainous area around the lake, upgrade the imagery of mountain meditation, create a forest healing base, and continue the visiting tradition of “climbing to temples and seeking Zen by rocks”; in the central lake area, upgrade the landscape imagery of celestial phenomena and night tours, create holographic boat banquets, and simulate moon shadows and misty rain. In terms of tour organization, a “Four-Image Poetic Passport” can be launched to guide tourists to collect check-in points of natural scenery/structures/religion/celestial phenomena, and guide the overall distribution of tourists. Develop “all-time viewing” products, set up moonlit tea parties, design “Misty Rain West Lake” special lines, and provide boating services in the fog, practicing the concept of “suitable for all four seasons” in Wulin old events

The strategies at the above three levels can, respectively, protect the cultural individuality and diversified imagery of the cultural heritage site from different spatial scales, enhance the modern adaptability of cultural heritage resources, and to a certain extent alleviate the problem of spatial imbalance commonly faced by modern tourism in heritage sites.

This research analyzed 2065 ancient poems related to West Lake and tourism to uncover landscape imagery and sightseeing behaviors, conducting correlation analysis to reveal the complexity of the compositional elements and hierarchical structure of West Lake’s poetic landscapes for the first time. These landscapes represent a multifaceted synthesis of nature and culture, reality and imagination. The literary works highlight distinct landscape images with notable spatial differentiation, where the natural environment is the primary influence, while socio-economic contexts and contemporary ideologies also significantly shape these heritage landscapes. Different landscape images inspire diverse tourism motivations, and the interactive elements within the site determine tourism behaviors. Based on the understanding of the relationship between landscape imagery composition and tourism behavior, strategies for the conservation and utilization of West Lake’s cultural landscape are proposed at the site, route, and regional levels.