Abstract

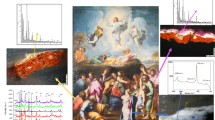

When studying pigment terminology in historical treatises on painting, it is often difficult to find physical materials that allow for reliable cross-referencing and verification. In 1680, Swedish artist and scholar Elias Brenner (1647–1717) published Nomeclatura et species Colorum Miniatae Picturae, Thet är: Förteckning och Proff på Miniatur Färgår, the earliest known document to list pigment names together with painted colour samples for reference. By combining nomenclature in French, Latin, and Swedish with actual pigment samples, this work provides a rare and valuable opportunity to validate historical terminology through direct pigment identification. Using non-invasive methods and portable instruments such as XRF, Raman spectroscopy, FORS, and FTIR, the study establishes for the first time a direct correlation between historical pigment names and their physical counterparts, offering unique insights into 17th-century Swedish pigment use and contributing significantly to the broader field of historical pigment research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Elias Brenner’s 1680 colour chart stands as the earliest known European example that systematically links pigment names with corresponding colour samples, making it an exceptionally valuable source for the study of historical pigment nomenclature, a field that typically depends on textual descriptions without accompanying physical references. This study was carried out as part of a broader research project1 aimed at contextualising the document and its terminology, with pigment analysis playing a crucial role in ensuring accurate identification and interpretation. As such, this paper focuses primarily on the identification of pigments, with some attention given to terminology, while the larger research project will offer a more comprehensive examination of the nomenclature in an upcoming publication.

The earliest known treatise on painting written by a practising artist is The Arte of Limning2 by Nicholas Hilliard (1547–1619), composed in England around 1600. In this manuscript, Hilliard provides detailed instructions on the selection, preparation, and application of pigments for his renowned portraits painted in gum Arabic on vellum. This was followed in 1648 by Edward Norgate’s Miniatura, or The Art of Limning3, the first printed treatise dedicated to the same method. Norgate was also the first to use the term “miniature” in print to describe limning, marking a shift toward the modern terminology for portrait miniatures. While both texts retain elements of the anonymous medieval recipe tradition used in art technology, they are distinguished by the authors’ personal insights into pigment use, though they lack physical samples. In 1647, Queen Christina of Sweden (reigned 1644–1654) introduced portrait miniature painting at her court by inviting foreign artists, including Pierre Signac (1623–1684) from France, who was appointed Court Miniaturist. This title was later held by Elias Brenner (1647–1717), the first native Swedish artist to specialise in miniature painting, having studied under Johannes Schefferus (1621–1679) at Uppsala University. In 1680, Brenner published Nomenclatura et Species Colorum Miniatae Pictura – Thet är: Förteckning och Proff på Miniatur Färgår (Latin and Swedish), which translates into English as A Nomenclature with Samples of the Colours Used in Miniature Painting. It is the earliest known printed document to pair pigment terminology with painted samples, offering a rare and invaluable resource for understanding Early Modern pigment terminology and the actual materials employed. The importance of Brenner’s work is further highlighted by Richard Waller’s 1686 publication of the first document featuring mixed colours, which explicitly acknowledges Brenner’s chart as its inspiration by saying “Having sometime since seen a table of the Simple Colours used in Limning and Painting, printed in the Year 1680, at Stockholm; (…)”4.

Currently, four surviving versions of Elias Brenner’s colour chart are known, each one a unique exemplar due to its hand-painted samples. This study has examined three of these: one held by the National Library in Stockholm, located at the Roggebiblioteket in Strängnäs (Wrangelske boksamlingen, gårdsarkivet W2G3, referred to here as W2G3) (Figs. 1 and S3), and two housed at Uppsala University Library: Palmsk. 332 (711–713), referred to as P332 (Fig. S9), and X219 (45–46), referred to as X219 (Fig. S10). Photographs including close-ups and documentation from the analysis process, are available in the supplementary material. The fourth version, held by the National Library (F1700 Fol.150), was not included in the study due to its incomplete set of colour samples. An overview of these documents is provided in Table 1.

Following the title page (Fig. S1) and a foreword (Fig. S2) explaining that the chart is intended for those wishing to learn the names and colours of pigments used in miniature painting, the next page presents a table titled Nomenclatura trilinguis, et genuina specimina colorum simplicium, quibus potissimum picturae miniatae artifices uti solent, in gratiam hujus artis cultorem edita per El. Brenner Stockholmiae A: 1680”. This translates as “a nomenclature in three languages with true colour samples of the pigments commonly used in miniature painting, for the benefit of practitioners of this art, published by Elias Brenner in Stockholm, 1680” (translation by Elena Dahlberg and Cecilia Rönnerstam). The table lists thirty pigments, organised by colour category, with each pigment name given in Latin, French, and Swedish, and accompanied by a hand-painted sample (Figs S3–12). One version of the charts (W2G3) also includes drawn tincture symbols for each colour group, reflecting Brenner’s interest in heraldry and his notable work for the Swedish House of Nobility.

The paper used in all known versions of Brenner’s colour chart consists of single-fold folios made from Western handmade rag paper, bearing watermarks with the coat of arms of Amsterdam, indicating a Netherlandish origin. While the pages of the two Uppsala versions have been trimmed to fit into 19th-century bound volumes, resulting in pigment overlap in P332 due to folding, the original dimensions of approximately 31 × 21 cm are preserved in the National Library’s W2G3 version, which remains a loose folio. The colour samples are painted on separate strips of paper that were affixed to the documents after printing, visible in (Fig. S13). In the X219 version, one sample, Fissile Candidum, has been mistakenly placed next to the term RUBEI rather than in its correct position (Fig. S12). The overall condition of the charts varies, both in terms of the paper and the pigment samples, with the National Library version generally better preserved than those at Uppsala. The paper shows rust-coloured spots caused by impurities introduced during its manufacture, with X219 displaying a darker tone and more prominent rust particles, likely indicating greater degradation. Most of the colour samples are applied in two or three layers, often visible to the naked eye, presumably to illustrate how colour and hue intensify with increasing thickness.

Pigments used in paint are either natural (mineral), applied after simple mechanical processing that does not alter their chemical composition, or manufactured (synthetic), produced through chemical reactions from raw materials. In the 17th century, although pigments were often commercially available, artists frequently refined them further by washing and grinding to achieve the desired quality and consistency, especially in miniature painting where paints were typically prepared by mixing pigment and binder directly at the time of use. Working with historical materials like these presents considerable challenges, as pigments may be mixed, oxidised, or faded, complicating analysis and interpretation. Additionally, the thin paint layers allow the underlying paper to influence the spectra, potentially hiding pigment data.

This study employed a range of non-invasive analytical techniques, in order to preserve the colour charts, as physical sampling was not an option. When these methods did not yield definitive results, we referred to existing studies and literature specific to this field for comparison and context. Visual examination was conducted using a Leica stereomicroscope M60. Due to the lack of scientific resources at the owning institutions and restrictions on transporting the documents, external partners and portable instruments were essential. The Nationalmuseum collaborated with the Swedish National Heritage Board to perform basic analyses based on available instruments (XRF, Raman spectroscopy, and multispectral imaging) on the two Uppsala University Library versions. A concurrent project with the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge enabled the addition of FORS analysis. Raman and FORS spectroscopy identified a wide range of pigments, and although these techniques operate at different scales and sensitivities, their combined use provided complementary insights, particularly in the analysis of blue and yellow areas. XRF helped narrow down pigment presence, identify impurities, and provide substrate information for lake pigments. The W2G3 version, held at the Rogge Library in Strängnäs and only discovered in 2024, after the project had started, was analysed using FTIR in reflection mode on selected areas, especially white samples, to refine results. Bruker Nordic provided support for this technique and contributed an additional Raman instrument, chosen for its ability to detect the widest range of pigments among those used on the Uppsala samples. Although it would have been ideal to apply all instruments to each version for statistical consistency, logistical constraints and issues of access made this impractical. Tables detail the techniques used per document, with FTIR discussed only where relevant due to its limited application and results. Chemical data is provided where known, particularly for mineral pigments, while substrate-based pigment compositions remain largely unknown or difficult to determine. Despite extensive research in both pigment terminology and scientific pigment analysis, the lack of cross-referenced sources has previously hindered systematic integration of these fields. This study bridges that gap for the first time, contributing new insights to the discipline and laying essential groundwork for future research.

Methods

X-ray fluorescence

The point analysis with X-ray fluorescence (µXRF) was conducted with an Artax 800 (Bruker, Berlin) equipped with a Mo tube and a polycapillary lens (spot size ˂100 µm), at 50 KV and 600 µA. The use of a Mo tube and the resulting overlap of peaks at 2.293 and 2.307 keV, for Mo Lα and S Kα respectively, makes it difficult to detect sulphur with this instrument configuration. Five points, 10 s each, were scanned for each colour sample generating a cumulative spectrum of 50 s. A baseline spectrum for the paper strip (Fig. S13) that the samples are painted on was established and signals for elements above taken as representative of the respective colour.

Raman spectroscopy

Two Raman systems were used for the study due to different instruments being available at different locations and time frames, as a result of constraints to how and when the documents could be accessed. Raman spectra of the version from Uppsala University Library were collected using an i-Raman Plus (B&W Tek, Newark, Delaware, U.S.) equipped with a BAC102 Lab Grade Raman probe for macroscopic collection (B&W Tek, Newark, Delaware, U.S.) (Fig. S14). The laser excitation wavelength was 785 nm with a power of 495 mW at the source, reduced to between 1 and 10% of the nominal power at the sample, depending on the surface and the pigment or dye analysed, and modulated in 1% steps. A fiber optic probe with a 200 µm core diameter with a head ensuring a working distance of 5.4 mm was used. The detector in the instrument was a TE cooled CCD and spectra were acquired over a range of 175–3110 cm⁻¹, each generated through the accumulation of 3–5 scans with a laser exposure time of 10–60 s per scan. Raman spectra at the Rogge Library were collected using a Bravo Handheld Raman spectrometer with dual-laser excitation (785 nm and 852 nm) (Bruker, Billerica, Massachusetts, U.S.). The spectra were collected over a range of 285–3200 cm−1, the instrument mounted vertically, facing downward from a custom-made metallic plate, allowing the folio to remain flat in a horizontal position beneath it during analysis (Figs. S15–17). To prevent any stray light from reaching the spectrometer, the entire setup was enclosed with a thick black cloth throughout the measurements. The device uses SSE (Sequentially shifted excitation) in order to mitigate fluorescence signals to ensure enhanced performance. With the metallic plate, a non-contact analysis could be ensured by maintaining a consistent working distance of approximately 2–3 mm above the document surface. Spectra were collected with an exposure time of 60–300 s depending on the sample. The software Essential FTIR, which is compatible with Raman spectra, was used for the identifications (Operant LLC, Monona, Wisconsin, U.S.) of spectra from the versions at Uppsala University Library and the Rogge Library, obtaining identification through comparing spectra in several Raman libraries (ForensicV2.lib, MinlabV5.lib, RF-pigmente_farbstoffe.lib, FT Minlab.lib, SemiCon.lib) with the obtained Raman spectra. The spectra have also been manually compared with several online reference libraries: RRUFF™ database (accessed 2024), Cultural Heritage Science Open Source (CHSOS) (Pigments-Checker Database, accessed 2024), Infrared and Raman Users Group (IRUG Spectral Database, accessed 2024) and Infrared and Raman Discussion Group (FT Raman Reference Spectra of Inorganics, accessed 2024)5,6,7,8.

Fiber optic reflectance spectroscopy

A portable FORS was used where the spectra were acquired in the 350–2500 nm range using a FieldSpec4 fibre optic spectroradiometer (ASD Inc., part of Malvern Panalytical) with an integrated light source and a bifurcated fibre-optic probe (Fig. S18). The instrument’s resolution is 3 nm at 700 nm, and 10 nm at 1400 and 2100 nm, the wavelength accuracy being 0.5 nm. The probe was hand-held above the area to be analysed at a 90° angle and at a distance of c. 5 mm, illuminating the samples using an ASD’s Hi-Brite probe (halogen bulb, 2901 K colour temperature). The spectrometer was calibrated against a white Spectralon® standard and spectra were collected and processed using ASD’s RS3 and ViewSpec Pro software. Each spectrum was the result of 64 accumulations and took approximately 8 s to collect. Spectral interpretation was based on in-house reference databases as well as the article by Aceto et al.9.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

An Alpha II FTIR spectrometer was used (Fig. S19). The Alpha II FTIR system, equipped with a diffusive reflectance allowing for non-contact analysis of the document’s surface collected spectra in the range of 4000–400 cm⁻¹ with a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹, averaging 32 scans per measurement to ensure high signal-to-noise ratios.

Multispectral imaging

The multispectral imaging process used in the project is based on technical photography with a full spectrum D810 camera (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan), the UV-IR-blocking filter removed at a Nikon service facility in Sweden. Images were captured using a VIS/IR Halogen lamp, Superphot 1000 W (Osram, Munich Germany) with 18 Antonello MSI System filters (CHOSOS, Viagrande, Italy) of 10 nm band pass width and specific mid-range points separated into relevant photosensor components, using Spectralon (Labsphere, North Sutton, New Hampshire, U.S.) standards for colour correction. The images were component separated using ImageJ image processing tool (National institutes of Health, Bethesda Maryland, U.S.) and colour corrected using RawTherapee (The RawTherapee Team, Budapest, Hungary). 8-bit (256 steps) colour depth value of each sample was captured over an area of 51 × 51 pixels in the middle of the sample or as close to the middle as possible in the case of uneven surfaces using the Eyedropper tool in Photoshop (Adobe, San Jose, California, U.S.). In cases where visible differences appeared across various areas of the sample, smaller regions of 30 × 30 pixels were captured at several locations to better represent the variation. These values were then used to create low resolution (18 data point) spectra of the samples.

Results

The type and nature of the paper (made mainly from hemp and linen rags at this time) was not analysed except for identification of elements with XRF in order to establish a baseline for determining the elements likely associated with the composition of each colour sample. The paper strips to which the paint samples are applied in the Uppsala versions were found to contain Cl, K, Ca, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, and Zn. Elements such as Ca, Fe, Mn and Cu may derive from the water used in the papermaking process. Paper fibres will very rapidly accumulate dissolved metals in water. Comparable baselines were established using FTIR, FORS, and Raman techniques. Both Ca and K are typically found in European paper from the period. The source of the Ca likely includes the water used in the making of the paper but may also be from wood ash lye soaps used for washing the original fabrics before they were turned into rags. The Ca may also derive from lime added to help facilitate swelling of the cellulose and maceration of the rags, or from the use of sizing containing Ca (from the bone or hide used to make it), and in some cases from other calcium compounds (such as calcium carbonate) presumably added as a whitener to counteract the yellowing effects from retting or the presence of iron in the water. The sources for the Cl and Zn are unclear, but other elements including Co and Ni have previously been identified in paper as possible mineral contaminants10. Potassium may derive from alum (potassium aluminum sulfate) used during the sizing procedure as a biocide, and as an additive to lessen the sensitivity of the final paper product to water11.

Gum Arabic was traditionally the binding medium employed in portrait miniature painting, as supported by documentary sources and the primary author’s direct experience working with the material. Its detection through non-invasive analytical methods, however, remains challenging. As a result, no conclusive analytical evidence confirming its presence was obtained, despite its presumed use. In the FTIR spectra from the limited number of samples in the W2G3 chart, absorption bands indicative of proteinaceous material were observed, including N–H stretching at 3290 cm⁻¹ and amide I and II bands at 1655 and 1550 cm⁻¹, respectively. These features may suggest the presence of glair (egg white) in the samples. As a slightly stronger binder than gum Arabic, glair could have been intentionally used to enhance pigment adhesion to the paper. However, it is more plausibly attributed to contamination, such as residues from inadequately cleaned brushes. In addition, two white samples exhibited bands associated with lipids—C–H stretching at 2850, 2920, and 2955 cm⁻¹, and C = O stretching at 1730 cm⁻¹ (see Fig. S20). Yet, it remains uncertain whether these signals reflect residues of a lipid-based binder, or rather, result from handling and contact with the painted samples over time.

Tables 2, 3, and 4 present the analytical results for the three examined versions of the colour chart, detailing the findings from each technique applied to the respective documents. Table 5 offers a consolidated summary of the identified pigments, where interpretations are informed by a combination of analytical data, historical terminology, and relevant literature.

Cerussa/le Blanc d’Espagne ou de Ceruse/Blyhwit and Fissile Candidum/Le Blanc d’Ardoise/Schiferhwit

Both white pigments, Cerussa/le Blanc d’Espagne ou de Ceruse/Blyhwit and Fissile Candidum/Le Blanc d’Ardoise/Schiferhwit, are remarkably well preserved in sample W2G3. In contrast, the Uppsala samples exhibit signs of oxidation (Figs. S11–12), visible as a reddish-brown discoloration commonly observed in historical artworks. In the case of the P332 sample, this colour shift may be attributed to physical contact with red pigments such as the Haematites and Ochra usta vel calcinata when the document is folded. However, in both Uppsala samples, XRF spectra indicate only lead being present. FORS data reveal a spectral band in the 1440–1450 nm range, attributed to the OH stretching overtone12, which is characteristic of hydrocerussite (see Fig. S21). Raman of the W2G3 samples identified a peak at 1052 cm−1, corresponding to cerussite in Cerussa, and an additional peak at 329 cm−1 in Fissile Candidum, indicative of Pb-O interactions within the cerussite crystal structure. FTIR of the same samples showed a prominent band between 1350 and1450 cm⁻¹, associated with the antisymmetric stretching mode of the carbonate ion (CO3)-2, along with spectral features charactersitic of both hydrocerussite (peaks at 3540 and 680 cm⁻¹) and cerussite (peaks at 2410 and 840 cm⁻¹)13, (see Fig. 2). The finds all point to the very common pigment lead white, which identification aligns well with the terminology. Cerussa and ceruse are historical synonyms for manufactured lead white, for which there are numeorus recipes producing lead carbonate, ever since antiquity. In the 17th century, the widely used “stack process” typically produced a combination of cerussite and hydrocerussite, which required washing to remove impurities and reduce the proportion of cerussite14. When lead white was mixed with chalk, it was sometimes referred to as Spanish white15, equivalent to Blanc d’Espagne. Blyhwit is the Swedish term for lead white used during the same period. Fissile Candidum is a less common term, likely drawn by Brenner from Schefferus discourse De Arte Pingendi16 (1669) about classical art theory and painting practices. This term can be traced through 18th-century sources17 and is also understood to denote lead white. Interestingly, the cerussite peaks appear more defined and intense in the Fissilie Candidum sample compared to the Cerussa in Brenner’s samples, suggesting that Fissile Candidum was a more refined variant.

FTIR spectra collected on the two white samples of W2G3; both spectra show the characteristic features of hydrocerussite (3540, 680 cm−1) and cerussite (2410, 840 cm−1). The intense band in the 1350–1450 range correspond to the (CO3)-2 mode of lead white. The organic matter is indicated with an asterisk (*), and a proteinaceous material corresponds to bands at 3290, 1655, 1550 cm−1. Spectral features at 2850, 2920, 2955, 1730 cm−1, corresponding to CH and CO stretching modes and characteristic of lipids, may be associated with the handling of the objects and not with the binder, as they appear only on the white areas and not on other colours analysed by FTIR.

Carmesinus color/Le Carmin/Carmin and Lacca florentina/La Lacque de Florence/Florentijn Lack

The first two red samples are both applied in multiple layers across all documents. The former exhibits a glossy and well-preserved deep red, while the latter presents a more opaque bluish-pink with more body.

In both samples, FORS analysis revealed two distinct absorbance maxima at 525 and 550 nm, along with an inflection point around 600 nm, features characteristic of red dyes of insect origin, such as kermes or cochineal. Substrate pigments, also known as lake pigments, are produced through the chemical process of laking, where soluble organic dyes are made insoluble by precipitation onto inorganic substrates, with variations in colour and hue resulting from the manufacturing process and different substrates. Although difficult to detect in the Carmesinus color samples, the presence of K and Al in both Lacca Florentina samples in the Uppsala versions suggests the use of a substrate pigment. Additionally, the small amount of iron detected in all three versions, identified as hematite in the W2G3 sample, indicates that it was likely intentionally mixed with red ochre to enhance the colour. The Carmesinus in P332 appears to contain a calcium based compound as seen in XRF, likely chalk, which may serve as a substrate or a filler. All terms refer to a substrate pigment derived from the red cochineal dye produced by scale insects, such as Dactylopius coccus L. Costa imported to Europe since the early1520’s18. While red substrate pigments were occasionally mixed with vermilion (see paragrah below) to enhance the paint’s hiding power, the Hg found in Lacca Florentina and the Pb found in the Carmesinus colour in both Uppsala versions are more likely due to contamination from the nearby cinnabar and lead white samples. Lacca Florentina is a trade name that suggests the pigment originated in Florence, Italy, a region well known in the 17th century for its trade and production of dyes and lake pigments.

Cinnabaris/Le Vermillon/Zinober

All samples of the vivid red pigment labelled Cinnabaris/Le Vermillon/Zinober are evenly applied and show no visible signs of degradation. Raman spectroscopy confirmed their composition as mercury sulphide (HgS), with characteristic spectral peaks at 253 and 342 cm⁻¹, and a shoulder or secondary peak at 284 cm⁻¹. These findings were further supported by XRF, which detected Hg and S, and FORS analyses, with the characteristic inflection point at 600 nm. The term vermilion refers to the synthetic form of mercury sulphide, which began to replace the naturally occurring mineral cinnabar from the early Middle Ages onward19. Although the terms cinnabar and vermilion were historically used interchangeably to describe both the natural and synthetic forms of mercury sulphide (HgS), by the 17th century vermilion had become the more prevalent term, particularly as Amsterdam rose to prominence as a major European centre for the pigment’s production and export20. While this study cannot conclusively differentiate between natural cinnabar and synthetic vermilion based solely on the available analytical data, however, the consistent use of terminology by Brenner, combined with the historical context of pigment manufacture and trade, strongly suggests that the samples in question are of the manufactured, synthetic variety.

Minium/La Mine de Plomb/Menia

The Minium/La Mine de Plomb/Menia samples show noticeable variation in appearance across the three versions. In samples W2G3 and P332, the pigment appears as a well-preserved vibrant orange, while in X219 it has oxidised into a crusty brown with a significant lacuna at the centre. XRF analysis confirmed the presence of lead, and both Raman and FORS analyses identified the pigment as lead oxide, (Pb₃O₄). A transition edge at 560 nm in the FORS spectra is consistent with the known spectral profile of this compound. Likewise, the sharp Raman band at 551 cm−1, and the presence of multiple structured bands between 100 and 550 cm−1 strongly support the identification of red lead. While the instrument does not allow for analysis of spectral features below 285 cm−1, where key indicators for litharge (e.g., the main band at 145 cm−1) are typically observed, the absence of broader bands within in the 285–550 cm−1 range suggests that there is no litharge present21. The presence of lead oxide indicates the use of red lead, a synthetic pigment equivalent to minium. While red lead has been manufactured since antiquity22, the natural mineral form of minium has only rarely been identified as a pigment. Although the instruments cannot tell them apart, and all of Brenner’s terms derive from the Latin minium, the samples are most likely composed of manufactured red lead.

Sangvis Draconis/Le Sang de Dragon/Drakeblodh

The Sangvis Draconis/Le Sang de Dragon/Drakeblodh samples, commonly known as Dragon’s blood, exhibit a deep brownish-red hue across all three versions, with the P332 sample appearing slightly darker than the others. FORS analysis revealed absorbance maxima at 520 and 560 nm, which are characteristic of an insect-based red organic dye. Although Dragon’s blood traditionally refers to a resin obtained from Dracaena trees and other related botanical sources23, the spectral data do not support the presence of a resin-based pigment in these samples. FTIR analysis further confirmed the absence of resin, and the FORS spectra instead suggest the use of an insect-derived dye, such as a cochineal-based lake, indicating that the pigment may have been substituted. Trace amounts of Fe, K, and Pb detected by XRF are likely the result of contamination from adjacent samples of Haematites and Minium. While a higher concentration of iron might have suggested deliberate mixing with an iron oxide like a red ochre (ochres are naturally occurring rocks and soils with variable colouration, primarily composed of iron oxides and hydroxides), the levels observed do not support this interpretation.

Haematites/La Sanguine/Blodsteen

Hematite, or iron oxide, was identified in all Haematites/La Sanguine/Blodsteen samples through both FORS and Raman. The FORS spectra displayed the characteristic sigmoid-shape, with inflection points around 580 nm and 700 nm, and an absorption at 850 nm24. Raman revealed distinct peaks at 224, 290, and 408 cm⁻¹. In addition to the typical ochre-associated elements such as Fe, Si, and K, XRF of the two Uppsala samples also detected small amounts of Ba and Ti. The consistent presence of Fe, Si, K, Ba, and Ti in both Uppsala documents may suggest that the same batch of pigment was used in their production. Notably, the Uppsala sample 332 also exhibited a spectral signature consistent with indigo, with Raman peaks at 248, 542, 754, and 1571 cm−¹. This indigo signal was absent in the W2G3 sample. Given the spatial separation between the Indicum and Haematites samples, contamination seems unlikely, suggesting that the indigo was deliberately mixed with the hematite. In this context, both the French and Swedish terms for the pigment refer to its colour rather than a specific geographical source. Rather than using the crushed mineral directly, the pigment likely derived from earths naturally rich in hematite.

Ochra Usta Vel Calcinata/L’Occre Calcinée/Brent Ocker

In the brick-orange-red samples labelled Ochra Usta Vel Calcinata/L’Occre Calcinée/Brent Ocker, FORS spectra show inflection points at 580 and 700 nm and an absorption at 850 nm, characteristic of a red iron oxide pigment. In addition to Fe as the element, XRF analysis of both Uppsala samples detected Si, K, and Ti, elements commonly associated with natural mineral impurities. Although the term Ochra Usta Vel Calcinata translates to “burned ochre” in all three languages, typically referring to yellow ochre that has been heated to produce red25, the sample from W2G3 appears to have been a naturally red ochre. The failure of the Uppsala samples to yield a Raman spectrum is likely due to the low crystallinity of the iron oxide mineral, a characteristic that can significantly hinder Raman signal detection.

Rubrica/La Terre Rouge/Brun Roth

The slightly darker pigment observed in the Rubrica/La Terre Rouge/Brun Roth samples was consistently identified as hematite across all versions of the charts, as indicated by distinct Raman peaks at 224, 291, 410, and 610 cm⁻¹, closely matching those found in the Haematites samples. While this similarity might suggest possible contamination, the consistent results across all samples make it more likely that Rubrica is composed of hematite itself. XRF analysis of both Uppsala samples detected Si, K, and Ba, elements commonly found in natural earth pigments. The terminology used reflects both the pigment’s composition and appearance: the Latin Rubrica historically referred to various red earth pigments, the French Terre Rouge translates directly to “red earth”, and the Swedish Brun Roth implies a brownish-red tone, which corresponds with the slightly darker hue observed in these samples compared to the Haematites.

Ochres are commonly found mixed with clays, aluminosilicates, and other minerals, which contribute to the presence of various trace elements such as Si and K. Ti and Ba may also occur naturally in ochres, typically associated with iron oxides, Ti often appearing as titanium oxide and Ba as barium sulphate (barite). The relative concentrations of these trace elements can offer clues about the geographical origin of the pigment. In the case of the two Uppsala samples, no significant differences were observed to suggest they came from different batches. However, it is noteworthy that Rubrica contained barium, while Ochra Usta Vel Calcinata contained titanium, indicating that these are two distinct iron oxide pigments likely sourced from different geographic regions.

Ultramarinum aut Cyprium/L’Outremer/Ultramarijn Blåt

All three Ultramarinum aut Cyprium/L’Outremer/Ultramarijn Blåt samples were found to contain lazurite, the principal component of ultramarine. This identification was confirmed through multiple analytical techniques: FORS detected a reflectance minimum at 600 nm, Raman spectroscopy revealed a characteristic peak at 543 cm⁻¹, and XRF analysis showed the presence of Ca, Si, Al, and S. These findings confirm that the pigment is indeed ultramarine, the highly valued blue pigment historically extracted from lapis lazuli. While the term ultramarinum reflects this origin, meaning “from beyond the sea”, the term Cyprium is a misattribution as it originally referred to high-quality azurite mined in Cyprus during antiquity26. In addition to lazurite, the two Uppsala samples also contain Cu, identified as azurite by the FORS absorptions at 2285 and 2350 nm, and Fe impurities from associated minerals such as goethite, indicated by Raman peaks at 387 and 1310 cm⁻¹. Initially suspected to be contamination, multispectral imaging (MSI) revealed a uniform distribution of azurite across the Ultramarinum samples. This is supported by the reflectance curve, which begins to rise around 700 nm, a typical indicator of azurite. Azurite is further characterised by a reflectance minimum near 640 nm, in contrast to ultramarine, which typically shows a minimum around 600 nm. The MSI analysis also reveals that the visual differences observed between different areas of the sample, particularly from approximately 730 nm, are due to layered paint application rather than differences in material composition. The spectral profiles from these areas display consistent behaviour, reinforcing the interpretation of compositional uniformity. Together, these findings suggest that azurite is intentionally mixed with lazurite in the Ultramarinum samples, rather than the result of incidental contamination (see Fig. 3). Deliberately extending ultramarine with azurite was a known method for reducing the cost of this otherwise expensive pigment. In contrast, the W2G3 sample shows no evidence of azurite and appears a brighter blue, indicating a higher-quality ultramarine with a greater concentration of lazurite and fewer impurities.

Montanum/La Cendre d’Azur/Bergblåt

In the Montanum samples, XRF analysis detected the presence of Cu, indicating the use of a copper-based pigment, which was confirmed to be azurite through characteristic FORS absorption bands at 1495, 2285, and 2350 nm, along with a distinct absorption feature at 640 nm. Raman spectroscopy further confirmed this identification in the W2G3 sample, showing characteristic peaks at 398, 546, 772, 843, 1095, and 1584 cm⁻¹. Additionally, Raman analysis of the same sample revealed minor traces of ultramarine, evidenced by bands at 546, 809, and 1095 cm⁻¹, likely due to contamination from the Ultramarinum sample positioned above. The term Montanum corresponds with the Latin and Swedish expressions for “mountain blue,” reflecting the pigment’s original mineral origin. Natural azurite was one of the most widely used blue pigments from antiquity until the 17th century, but by the late 1600 s it was increasingly replaced by verditer, a more affordable synthetic copper-based blue pigment27. XRF analysis of the Uppsala samples also revealed traces of Cl, which some have speculated might indicate the presence of verditer; however, recent research28 has questioned this interpretation, leaving the presence of Cl unexplained. Verditer typically exhibits more uniformly sized and rounded particles compared to natural azurite, but since no sampling was permitted for microscopic analysis, it remains uncertain which version of the pigment Brenner actually employed.

Indicum/l’Inde/Indie blåt

All of the dark blue samples labelled Indicum/l’Inde/Indie blåt have been identified as indigo through FORS, which showed an absorption maximum at 660 nm, and confirmed by Raman spectroscopy with characteristic peaks at 544, 597, 757, 867, 1145, 1311, 1363, 1463, and 1574 cm⁻¹. XRF analysis also detected the presence of Si, K, Fe, and Ti, along with a small amount of Cu, likely due to contamination from the azurite sample above. In 17th-century Europe, imported indigo derived from the Indigofera tinctoria plant increasingly replaced woad (Isatis tinctoria) as the primary source of blue dye29. Although the non-invasive methods used in this study cannot distinguish between these two sources, the pigment is referred to as indigo in accordance with Brenner’s terminology. This is further supported by the samples’ deep, intense blue colour, which contrasts with the weaker tinting strength typically associated with woad. The elements Si, K, Fe, and Ti found in both Uppsala samples may occur naturally in the indigo plant, or be introduced during the production process or through adulteration30.

Chrysocolla/le verd de Montagne ou de terre/Bergh grönt

The green pigments begin with Chrysocolla/le verd de Montagne ou de terre/Bergh grönt, which appear thick and compact with a pale bluish-green hue. Historically, the term “chrysocolla” is widely known to have caused confusion in pigment nomenclature, having been used to describe a variety of green pigments. XRF analysis of the Uppsala samples detected the presence of Cu and Cl, while FORS revealed characteristic absorption bands at 1465, 1990, 2160, 2342, and 2470 nm, as seen in (Fig. 4). According to previous studies31,32,33, these bands correspond to atacamite (Cu₂Cl(OH)₃), with the 1465 nm band attributed to the first overtone of the OH stretching mode and the 2342 nm band to combination bands involving OH stretching and bending modes. Atacamite is therefore identified as the primary green pigment present in these samples. The absence of other green copper-based pigments, particularly verdigris, which was not detected by either FORS or Raman spectroscopy, suggests that the atacamite present is a pure compound, indicating that it was produced intentionally for use as a pigment rather than being a byproduct of copper corrosion or degradation. However, the presence of other copper pigments in smaller quantities cannot be ruled out, as they may fall below the detection limits of the analytical techniques used. Although atacamite is not commonly found in miniature painting, it was widely used in medieval Swedish mural painting, well before Brenner’s time34.

Aerugo/le verd de gris/Spansk grönt and Crystallus viridis aeris/le verd de gris cristalicée/Distilerat spansk grönt

The pigments labelled Aerugo/le verd de gris/Spansk grönt and Crystallus viridis aeris/le verd de gris cristalicée/Distilerat spansk grönt are all copper-based greens, as confirmed by the identification of Cu through XRF analysis. The latter term refers to a more refined or distilled form of the pigment, which involves the separation of basic and neutral copper acetates. XRF analysis of both Uppsala samples also revealed the presence of K, suggesting that the pigments may have been washed with potassium lye during preparation. A small amount of Cl detected in the X219 Crystallus viridis aeris sample is likely due to contamination from the nearby atacamite sample, and the presence of Pb may indicate that the pigment was mixed with lead white to adjust its colour. While both green samples in P332 exhibit characteristics of verdigris, with a FORS reflectance minimum at 720 nm, the X219 samples were identified as copper resinate, showing a reflectance minimum at 690 nm (see Fig. 4). This interpretation is supported by slight visual differences, where the X219 samples appear glossier and have a colder, bluish tone, whereas the P332 samples display a warmer green hue.

Succus foliorum gladioli/le verd d’Iris/Iris grönt and Succus viridis f. Rhamni/le verd de vessie/Safft grönt

The two thinly applied dark greenish samples labelled Succus foliorum gladioli/le verd d’Iris/Iris grönt and Succus viridis f. Rhamni/le verd de vessie/Safft grönt are described in the terminology as plant-based pigments, a classification supported by FORS analysis, which identified them as organic greens with a reflectance minimum around 605 nm, a spectral feature typically associated with pigments such as iris green and sap green. Succus foliorum gladioli, or iris green, was commonly produced from extracts of irises or lilies, while Succus viridis f. Rhamni, known in English as sap green, is traditionally derived from ripe buckthorn berries, as indicated by the Latin term Rhamni35. However, due to their organic composition, these pigments are inherently difficult to identify with greater precision using non-invasive techniques. XRF analysis of the Succus foliorum gladioli samples detected a small amount of Pb, which may suggest the use of lead white to adjust the colour, while the presence of Cu is likely due to contamination from nearby copper-based green pigments.

Ochra Plumbana/le Massicot/Bly gult

The first yellow pigment is Ochra Plumbana/le Massicot/Bly gult, which appears as an evenly applied, dense, and very pale yellow across all versions. In the Uppsala samples, XRF detected both Pb and Sn, and Raman confirmed the presence of lead-tin yellow type I, with prominent peaks at 130, 196, 275, 292, 457, and 525 cm⁻¹. While the terms ochra plumbana and bly gult both translate to “lead yellow,” the term massicot has historically referred to various lead-based compounds, though the most commonly encountered pigment under this name is lead-tin yellow36. Although the Raman spectrum for sample W2G3 did not yield a definitive result, likely due to the characteristic peaks falling outside the instrument’s detection range, the sample’s distinctive pale yellow hue strongly suggests that the same pigment was used.

Gutta Gambae f. Camboya/la Gomme Gutte/Gummi gutta

The terms Gutta Gambae f. Camboya/la Gomme Gutte/Gummi gutta all refer to gamboge, a vivid yellow gum resin derived from trees of the Guttiferae family, native to Southeast Asia and exported to Europe since the early 17th century37. All analysed samples display a strikingly intense yellow hue and a thick consistency that clearly sets them apart from the other pigments. In the Uppsala version, Raman successfully identified the substance as gamboge, with peaks at 1243, 1280, 1592, and 1629 cm⁻¹. Although the spectrum was weak, key diagnostic bands were present and matched reference spectra, supporting the identification. FORS analysis, however, did not yield conclusive results, and the absence of detectable elements in XRF further supports the identification of an organic colourant.

Auripigmentum/l’Orpin/Auripigment

The next yellow pigment is Auripigmentum/l’Orpin/Auripigment, referring to orpiment, named for its resemblance to the colour of gold. This pigment was identified in all samples by distinct Raman peaks at 290, 309, and 380 cm⁻¹, along with the presence of As and S detected through XRF. In the Uppsala P332 sample, sharp, well-resolved Raman peaks at 153, 178, 290, and 353 cm⁻¹ indicate that the orpiment is natural rather than synthetic, particularly the peak at 153 cm⁻¹, which suggests long-range crystalline order38. The nature of orpiment in the W2G3 sample could not be determined because the Raman spectrometer used for the analysis only detects signals above 285 cm⁻¹, thereby missing the characteristic peak at 153 cm⁻¹. Although synthetic orpiment has been produced since medieval times39, the sample in Brenner’s collection appears to originate from the naturally occurring mineral form.

Color ex succo foliorum betulae/le stil de grain/Schut gult

The next yellow pigment, Color ex succo foliorum betulae/le stil de grain/Schut gult, presents an intriguing case. While the French and Swedish terms refer to a substrate pigment typically derived from unripe buckthorn berries40, as opposed to the ripe used for a green colour, the Latin name suggests the use of birch leaves. This may point to a Swedish variation of the pigment. However, none of the analytical techniques employed provided conclusive results, aside from the detection of Ca and a small amount of Pb. The calcium likely originates from the substrate or possibly a filler, while the lead may be either a contaminant or an intentional addition of lead white to adjust the colour.

Ochra vulgaris f. fil./l’Ocre de ruë/Ocker

All terms of the powdery dark yellow pigment Ochra vulgaris f. fil./l’Ocre de ruë/Ocker refer to yellow ochre. XRF detects Fe, Si, and Ti, along with trace amounts of K and Pb, all elements commonly associated with natural yellow iron oxides41. The sigmoid-shaped spectra collected by FORS, with an inflection point at 550 nm and absorption bands at 640 and 890 nm, are characteristic of a yellow iron oxide. Raman spectroscopy revealed distinct peaks at 243, 297, 387, 482, and 546 cm⁻¹, confirming the presence of goethite, the primary colouring agent of yellow ochre.

Sandaracha/la Sandaraque/Rusch gult

The light orange pigment Sandaracha/la Sandaraque/Rusch gult has been identified as realgar. FORS revealed an inflection point at 540 nm, and XRF detected As and S, indicating the presence of an arsenic sulphide. This identification was confirmed by Raman spectroscopy, which detected realgar in the Uppsala samples through characteristic peaks at 141, 163, 184, 217, and 358 cm⁻¹. Notably, sample W2G3 exhibited a broad peak at 345 cm⁻¹, suggesting of an intermediate phase between realgar and pararealgar. Although realgar could be synthesised by heating orpiment and is mentioned in historical sources, including classical texts where Pliny referred to it as sandaracha, its use as a pigment appears to be relatively rare42. However, it has been identified in works by Nicholas Hilliard43,44.

Calculus fellis bubuli/la Pierre de fiel/Gallsteen

The nomenclature Calculus fellis bubuli/la Pierre de fiel/Gallsteen suggests the use of bovine gallstone, a material historically employed to produce a dark yellow colour. This pigment proved difficult to identify conclusively; however, its presence is strongly supported by the detection of bilirubin in sample W2G3, particularly the distinct peak at 1619 cm⁻¹, consistent with C = C and C = O vibrational modes in bilirubin’s conjugated system. Additional supporting features include multiple bands in the 1200–1350 cm⁻¹ range from C–N to C–H deformations, as well as several C–C, C–N, and pyrrole-related bands in the 950–1050 cm⁻¹ range45. The absence of a sharp 1284–1304 cm⁻¹ band suggests the material is not pure bilirubin but more likely calcium bilirubinate46. This interpretation is further supported by the presence of Ca in both Uppsala specimens seen by XRF, consistent with calcium bilirubinate, a major component of gallstones47. Moreover, the lack of a C = O stretching band at 1680 cm⁻¹ and the absence of strong aromatic C–C and C–H deformation bands at 1240, 1330, and 1600 cm⁻¹ help rule out plant-based inks48. Taken together, these findings support the hypothesis that the pigment was derived from gallstone.

Umbra/la Terre d’Ombre/Umbra

The thickly applied greenish-brown samples of Umbra/la Terre d’Ombre/Umbra were identified as umber in the Uppsala versions based on XRF analysis, which revealed the combined presence of Fe and Mn, elements characteristic of natural umber49. Raman on the W2G3 sample did not yield any results. However, the presence of quartz-like particles observed under magnification in the X219 sample suggests it may originate from a different source than the other two, or reflect differences in the degree of pigment preparation.

Terra Coloniensis/la Terre de Cologne/Kölnisk Jordh

All samples named Terra Coloniensis/la Terre de Cologne/Kölnisk Jordh, translated as Cologne Earth, are thinly applied dark brown paints with low opacity, exhibiting a fractured surface pattern under magnification. Although the pigment was originally derived from peat, this material is difficult to detect analytically, and both the terminology and composition appear to have become obscured over time50. While Fe, Ca, and smaller amounts of Mn have been reported in association with organic pigments made from humic earth51, the Fe and Mn detected here may also be contaminants from the umber samples above. The pigment is likely an organic brown, but it remains uncertain whether it corresponds to the peat-based Cologne Earth known to have been used in the 17th century, as suggested by Brenner’s terminology.

Elephantinum/le Noir d’Ivoire/Benswart

The Elephantinum/le Noir d’Ivoire/Benswart, a brownish-black pigment, was analyzed using XRF, which detected Ca and P, while Raman spectroscopy revealed characteristic peaks for amorphous carbon at 1329 and 1594 cm⁻¹. The terminology includes both ivory black (Latin and French) and bone black (Swedish), reflecting the historical ambiguity surrounding these terms. Although recipes for producing black pigment from true ivory do exist, mentioned by both Hilliard and Norgate, the term “ivory black” was often used more broadly to describe pigments made from either charred ivory or bone, often to imply a certain level of quality52. Since both dentine (ivory) and bone are composed of hydroxyapatite and calcium sulphate, primarily identifiable through the presence of Ca and P, a more precise identification is difficult. The pigment could have been produced from either material.

Atramentum Indicum/l’Encre de Chine/Indianiskt Bleck

The lighter, more greyish Atramentum Indicum/l’Encre de Chine/Indianiskt Bleck was identified as a carbon-based black through Raman. This is supported by XRF analysis, which showed no presence of Ca or P, elements typically associated with bone or ivory black. The greyish tone is somewhat puzzling, as carbon blacks are generally stable; however, it has been reported that incompletely carbonized charcoal can turn grey over time due to the oxidation of residual tarry substances53. There is no indication of a white pigment being mixed in. The terminology appears to refer to ink, but this doesn’t necessarily imply that the material was used as such, in fact, historically, the term Atramentum has been applied to various black pigments54. The Fe and Pb detected by XRF may be residues from the manufacturing process, possibly introduced if the pigment was scraped from a metallic surface, though the exact origin remains uncertain. Using MSI, it was immediately apparent that Atrum Fuliginosum and Elephantinum. Shared features in the near-UV region that were not present in Atramentum Indicum (see Fig. 5), possibly indicating a difference in graphitic structure. This suggests that Atramentum Indicum is more amorphous or impure, supporting the conclusion that it is a plant-based carbon black, in contrast to both Atrum Fuliginosum and Elephantinum55.

Atrum fuliginosum/le Noir de Fumée/Kinswart

Atrum fuliginosum/le Noir de Fumée/Kinswart appears somewhat bluer than the Elephantinum samples across all versions. The terminology refers to soot collected from burning organic materials, typically gathered from chimneys or metallic surfaces, a pigment now commonly known as lamp black. Raman spectroscopy identified the W2G3 sample as carbon black, consistent with a soot-based pigment. In the Uppsala samples, however, XRF revealed the presence of Ca and P in lower but comparable amounts to those found in Elephantinum. However, due to variations in the data across different instruments and charts, it remains unclear whether we are observing a mixture of components or distinct materials in each dataset. As a result, no definitive conclusion can be drawn.

The results further suggest that elemental migration, primarily of Pb, Fe, and Cu from lead white, iron-, and copper-based pigments, has occurred, leading to contamination of adjacent paint samples. This is exemplified by the unexpected level of Pb detected in Sangvis Draconis, which appears to be attributable to its proximity to Minium (see Fig. 6). Even samples located further away exhibit a surprising trend that may indicate broader contamination. This warrants further investigation through XRF mapping of the paper between the samples to detect evidence for the presence of a diffusion gradient or particle transfer through handling. The extent of this phenomenon was unforeseen and had to be taken into account when interpreting the analytical results.

Discussion

Elias Brenner’s 1680 manuscript, Nomenclatura et Species Colorum Miniatae Pictura, marks a groundbreaking moment in the history of artists’ materials, as the first known pigment list to include corresponding painted samples as colour references. This study presents a rare opportunity to, for the first time, validate historical pigment terminology by directly analysing the pigments in three versions of the document. The complex nature of the aged materials, combined with the limited capabilities of available instruments and occasionally ambiguous spectral data, made the analysis challenging. Consequently, not all pigments could be identified with complete certainty. The findings suggest that the version held at the National Library (W2G3) is particularly well-preserved, featuring finer details such as hand-drawn colour symbols and the use of pure, unmixed pigments. In contrast, the two Uppsala versions are less detailed and include several mixed pigments, such as ultramarine extended with azurite and haematite containing indigo, raising the possibility that they may not have been prepared by Elias Brenner himself, highlighting the importance of provenance in historical documents. The results contribute to the broader field of historical pigment research, offering insights into the use of pigments across various painting techniques and historical contexts.

The white samples labelled Cerussa and Fissile Candidum are composed of a mixture of cerussite and hydrocerussite commonly known as lead white. However, the more sharply defined peaks of cerussite observed in the Fissile Candidum samples suggest a more refined form of lead white, likely due to an additional washing step during the pigment’s preparation. The red pigments Carmesinus color and Lacca Florentina are substrate-based lake pigments, meaning that organic colourants have been precipitated onto inorganic substrates. Both are likely derived from cochineal, which was the predominant source of red lake pigments in Europe during the period. The Lacca Florentina appears to include red ochre, possibly added to intensify or deepen the colour. The Cinnabaris samples were identified as mercury sulphide, most likely corresponding to vermilion, the synthetic form of the naturally occurring mineral cinnabar, which was being manufactured in the Netherlands at the time. The Minium samples were identified as minium, or more likely the synthetic equivalent red lead, widely produced and used since antiquity. Sangvis Draconis appears to be derived from an insect-based dye, rather than the plant resin traditionally associated with the Dracaena species, as the name might suggest. Haematites, Ochra usta vel calcinata, and Rubrica are all red ochres, composed of iron oxide, with hematite specifically identified in both the Haematites and Rubrica samples. The Haematites samples from Uppsala are further mixed with a small amount of indigo. In the National Library version, Ultramarinum was identified as pure lazurite, whereas in the Uppsala versions, it appears mixed with azurite, a common practice at the time to extend and reduce the cost of the expensive ultramarine pigment. The Montanum samples consistently contain azurite; however, it remains unclear whether the pigment originates from a natural mineral source or the synthetic variant known as verditer. Additionally, the presence of Cl in these samples cannot currently be explained. Indicum contains indigo, though it has not been possible to determine whether it derives from woad (Isatis tinctoria) or from the Indigofera plant. However, the depth of colour, combined with the fact that indigo from Indigofera was indeed being imported into Europe during this period, suggests the latter as a likely source. Among the green pigments, Chrysocolla was identified as atacamite, and its high purity suggests it was likely a deliberately synthesised pigment rather than a product of copper corrosion or a byproduct of copper mining. Aerugo and Crystallus virides aeris are both forms of verdigris, referring to a group of basic copper acetates. According to the terminology, the latter is expected to be crystallised, indicating a higher level of purity. In one of the Uppsala versions, Crystallus virides aeris appears mixed with resin, forming a copper resinate. This is somewhat unexpected, as copper resinate is typically produced by reacting a copper salt with a natural resin and was commonly used as a glaze, either over other green pigments or on metal surfaces. Given the context, this may reflect an unintentional mistake by the artist. Succus foliorum gladioli and Succus viridis Rhamni are both substrate pigments which, while possibly corresponding to iris green and sap green, as suggested by their terminology and referenced literature, cannot be further identified. The yellow pigment Ochra plumbana was identified as lead-tin yellow type I. Gutta gambae corresponds to gamboge, a pigment derived from the gum resin of trees in the Guttiferae family, imported from Asia during the period. Auripigmentum is natural orpiment, a bright yellow arsenic sulphide mineral, while the pigment named Color ex succo foliorum Betulae suggests birch leaves as the source, though its exact origin remains undetermined. Sandaracha was identified as realgar, a red-orange arsenic sulphide that is not often found as a pigment. Calculus fellis bubuli appears to correspond to gallstone in the National Library sample, as indicated by the detection of bilirubin and calcium; however, its identification remains inconclusive in the Uppsala samples. Umbra was identified as umber, and Terra Coloniensis is likely of organic origin, although its precise composition remains unclear. The black pigment Elephantinum was identified as calcium phosphate, indicating that it contains calcined ivory or bone, Atramentum Indicum was determined to be based on vegetal carbon. The results from Atrum fuliginosum are inconsistent: the sample from the National Library indicates the presence of carbon black, while the Uppsala charts show signals for calcium and phosphorus, pointing to bone or ivory content. Both could represent pure substances or mixtures, but based on the current data, it is not possible to determine this with certainty. Some substrate pigments appear to have been extended with chalk, and a few show signs of manipulation with lead white.

In summary, while these findings are particularly significant for the study of portrait miniature painting in Sweden during the latter half of the 17th century, many of the identified pigments were used across a wide range of periods and artistic techniques. This makes the study a broadly valuable resource for understanding historical pigment use and terminology. As such, it offers insights that are not only relevant to the historical context but also contribute meaningfully to ongoing research, the preservation of cultural heritage, and the wider field of art history.

Data availability

All data is available upon request. Instruments reports can be found on Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15114005.

References

The study was initiated through Cecilia Rönnerstam’s research project about Elias Brenner’s Nomenclatura at the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm. https://www.nationalmuseum.se/en/pigments-used-in-early-modern-portrait-miniature-painting-in-sweden.

Hilliard, N. A Treatise Concerning The Arte Of Limning (eds Cain, T. G. S. & Thornton, R. K. R.) (Mid Northumberland Arts Group in association with Carcanet New Press,1981).

Norgate, E. Miniatura Or The Art Of Limning (eds Muller J. M. & Murrell, J.) (Yale Univ. Press for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 1997).

Waller, R. A catalogue of simple and mixt colours, with a specimen of each colour prefixt to Its proper name. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 6, 24–32. (Published by the Royal Society, 1686).

Lafuente, B., Downs, R. T., Yang, H. & Stone, N. The power of databases: the RRUFF project. In Highlights in Mineralogical Crystallography (eds Armbruster, T. & Danisi, R. M.) 1–30 (De Gruyter, 2015).

Dent, G. F. T. Raman reference spectra of inorganics. Infrared and Raman Discussion Group. https://www.irdg.org/ijvs/library-of-spectra (2024).

Caggiani, M. C., Cosentino, A. & Mangone, A. Pigments Checker version 3.0, a handy set for conservation scientists: a free online Raman spectra database. Microchem. J. 129, 123–132 (2016).

Price, B. A., Pretzel, B. & Lomax, S. Q. (eds) Infrared and Raman Users Group Spectral Database, Vols. 1–2 (IRUG, Philadelphia, 2009).

Aceto, M. et al. Characterisation of colourants on illuminated manuscripts by portable fibre optic UV-visible-NIR reflectance spectrophotometry. Anal. Methods 6, 1488–1500 (2014).

Manso, M., Costa, M. & Carvalho, M. L. X-ray fluorescence spectrometry on paper characterization: a case study on XVIII and XIX century documents. Spectrochim. Acta B 63, 1320–1323 (2008).

Barrett, T. et al. Paper through time: non-destructive analysis of 14th- through 19th-century papers. University of Iowa. http://paper.lib.uiowa.edu/index.php (Last modified May 04, 2022).

Moreau, R. et al. A multimodal scanner coupling XRF, UV–Vis–NIR photoluminescence and Vis–NIR–SWIR reflectance imaging spectroscopy for cultural heritage studies. X-Ray Spectrom. 53, 271–281 (2003).

Miliani, C., Rosi, F., Daveri, A. & Brunetti, B. Reflection infrared spectroscopy for the non-invasive in situ study of artists’ pigments. Appl. Phys. A 106, 295–307 (2012).

Stols-Witlox, M., Megens, L. & Carlyle, L. ‘To prepare white excellent…’: reconstructions investigating the influence of washing, grinding and decanting of stack-process lead white on pigment composition and particle size. The artist’s process: Technology and interpretation (eds Eyb-Green, S., Townsend, J. H., Clarke, M., Nadolny, J., Kroustallis, S.) 112–129 (Archetype Publications, 2012).

Harley, R. D. Artists’ Pigments c. 1600-1835 2nd edn, 165 (Archetype Publications, 2011).

Schefferus, J. Graphice Id Est, De Arte Pingendi Liber Singularis Cum Indice Necessario (Ex officina Endteriana, 1669).

Jones, W. J. Historisches Lexikon Deutcher Farbbezeichnunge 2469 – 2470 (Akademie Verlag, 2013).

Schweppe, H. & Roosen-Runge. H. Carmine – cochineal carmine and kermes carmine. In Artists’ Pigments A Handbook Of their History And Characteristics, Vol. 1 (ed. Feller, R. L.) 256 (National Gallery of Art, 2012).

Gettens, R. J., Feller, R. L. & Chase, W. T. Vermilion and cinnabar. In Artists’ Pigments A Handbook Of their History And Characteristics, vol. 2 (ed. Roy, A.) 160 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, in association with Oxford University Press, 1993).

Van Schendel, A. F. E. Manufacture of vermilion in 17th century Amsterdam. The pekstok papers. Stud. Conserv. 17, 70–82 (1972).

Pasteris, J. D. et al. Worth a closer look: Raman spectra of lead-pipe scale. Minerals 11, 1047 (2021).

Eastaugh, N., Walsh, V., Chaplin, T. & Siddall, R. Pigment Compendium A Dictionary Of Historical Pigments 264 (Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, 2004).

Eastaugh, N., Walsh, V., Chaplin, T. & Siddall, R. Pigment Compendium A Dictionary Of Historical Pigments, 142−143 (Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, 2004).

Botticelli, M. et al. Colorimetric characterization of ochres in a Palaeolithic flint pebble from Maschio dell’Artemisio, Latium, Italy. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 43, 103420 (2022).

Helwig, K. Iron oxide pigments: natural and synthetic. In Artists’ Pigments A Handbook Of Their History And Characteristics, Vol. 4 (ed. Berrie, B.) 46 (National Gallery of Art, Washington in association with Archetype Publications, 2007).

Rönnerstam, C. Lost in translation: the changing meaning of Cyprium from azurite to ultramarine` in Work in progress: the artists’ gestures and skills explored through art technological source research. In Proc. Ninth Symposium of the ICOM-CC Working Group on Art Technological Source Research, Paris, 24-25 November 2022, 156–157 (ICOM-CC, 2022).

Gettens, R. J. & West Fitzhugh, E. Azurite and blue verditer. Artists’ Pigments A Handbook Of Their History And Characteristics, Vol. 2 (ed. Roy, A.) 31 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, in association with Oxford University Press, 1993).

Purdy, E. H. et al. Characterisation of rouaite, an unusual copper-containing pigment in early modern English wall paintings, by synchrotron micro X-Ray diffraction and micro X-Ray absorption spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. A 130, 817 (2024).

Eastaugh, N., Walsh, V., Chaplin, T. & Siddall, R. Pigment Compendium A Dictionary Of Historical Pigments 195 (Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, 2004).

van Eikema Hommes, M. H. Discoloration in renaissance and baroque oil paintings. instructions for painters, theoretical concepts, and scientific data. [PhD thesis, fully internal, Universiteit van Amsterdam] https://hdl.handle.net/11245/1.194612 (2022).

Liu, W., Li, M., Wu, N., Liu, S. & Chen, J. A new application of fiber optics reflection spectroscopy (FORS): identification of “bronze disease” induced corrosion products on ancient bronzes. J. Cult. Herit. 49, 19–27 (2021).

Catelli, E. et al. A new miniaturised short-wave infrared (SWIR) spectrometer for on-site cultural heritage investigations. Talanta 218, 121112 (2020).

Catelli, E., Sciutto, G., Prati, S., Jia, Y. & Mazzeo, R. Characterization of outdoor bronze monument patinas: the potentialities of near-infrared spectroscopic analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 25, 24379–24393 (2018).

Nord, A. G. & Tronner, K. The frequent occurrence of atacamite in medieval swedish murals. Stud. Conserv. 63, 477–481 (2018).

Eastaugh, N., Walsh, V., Chaplin, T. & Siddall, R. Pigment Compendium A Dictionary Of Historical Pigments 332–333 (Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, 2004).

Harley, R. D. Artists’ Pigments c. 1600-1835, 2nd rev. edn, 96 (Archetype Publications, 2011).

Eastaugh, N., Walsh, V., Chaplin, T. & Siddall, R. Pigment Compendium A Dictionary Of Historical Pigments 164–165 (Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, 2004).

Zaleski, S., Takahashi, Y. & Leona, M. Natural and synthetic arsenic sulfide pigments in Japanese woodblock prints of the late Edo period. Herit. Sci. 6, 32 (2018).

Harley, R. D. Artists’ Pigments c. 1600-1835, 2nd edn, 94 (Archetype Publications, 2011).

Eastaugh, N., Walsh, V., Chaplin, T. & Siddall, R. Pigment Compendium A Dictionary Of Historical Pigments 353 (Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, 2004).

Volpi, F., Vagnini, M., Vivani, R., Malagodi, M. & Fiocco, G. Non-invasive identification of red and yellow oxide and sulfide pigments in wall paintings with portable ER-FTIR spectroscopy. J. Cult. Herit. 63, 158–168 (2023).

Eastaugh, N., Walsh, V., Chaplin, T. & Siddall, R. Pigment Compendium A Dictionary Of Historical Pigments 318–319 (Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, 2004).

Burgio, L., Cesaratto, A. & Derbyshire, A. Comparison of English portrait miniatures using Raman microscopy and other techniques. J. Raman Spectrosc. 43, 1713–1721 (2012).

Fiorillo, F., Burgio, L., Kimbriel, C. S. & Ricciardi, P. Non-invasive technical investigation of English portrait miniatures attributed to Nicholas Hilliard and Isaac Oliver. Heritage 4, 1165–1181 https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4030064 (2021).

Yang, B. et al. Normal coordinate analysis of bilirubin vibrational spectra: effects of intramolecular hydrogen bonding. Spectrochim. Acta A 49, 1735–1749 (1993).

Stringer, M. et al. Gallstones in New Zealand: composition, risk factors and ethnic differences. ANZ J. Surg. 83, 575–580 (2012).

Palchik, N. A. & Moroz, T. N. Polymorph modifications of calcium carbonate in gallstones. J. Cryst. Growth 283, 450–456 (2005).

Huguenin, J., Hamady, S. O. S. & Bourson, P. Monitoring deprotonation of gallic acid by Raman spectroscopy. J. Raman Spectrosc. 46, 1062–1066 (2015).

Eastaugh, N., Walsh, V., Chaplin, T. & Siddall, R. Pigment Compendium A Dictionary Of Historical Pigments 377–378 (Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, 2004).

Harley, R. D. Artists’ Pigments c. 1600-1835, 2nd edn, 150 (Archetype Publications, 2011).

Feller, R. L. & Johnston Feller, R. M. Vandyke brown, Cassel earth, Cologne earth. In Artists’ Pigments A Handbook Of their History And Characteristics, Vol. 3 (ed. West Fitzhugh, E.) 175 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, in association with Oxford University Press, 1997).

Eastaugh, N., Walsh, V., Chaplin, T., & Siddall, R. Pigment Compendium A Dictionary Of Historical Pigments 204 (Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, 2004).

Winter, J. & West Fitzhugh, E. Pigments based on carbon. In Artists’ Pigments A Handbook Of Their History And Characteristics, Vol. 4 (ed. Berrie, B.) 14 (National Gallery of Art, Washington in association with Archetype Publications, 2007).

Winter, J. & West Fitzhugh, E. Pigments based on carbon. In Artists’ Pigments A Handbook Of Their History And Characteristics, Vol. 4 (ed. Berrie, B.) 5 (National Gallery of Art, Washington in association with Archetype Publications, 2007).

Tomasini, E. P. et al. Identification of carbon-based black pigments in four South American polychrome wooden sculptures by Raman microscopy. Herit. Sci. 3, 19 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their sincere gratitude for the cooperation and support received from numerous individuals and institutions. Special thanks are extended to Anders Nilsson and Erik Bernmalm at Bruker Nordics AB for conducting the Raman and FTIR analyses of the document held at the Rogge Library in Strängnäs, and for generously allowing the use of their results. We are also deeply grateful for the expert consultation and generous support provided by Dr Elena Dahlberg, Dr Doris Oltrogge at the CICS Cologne Institute of Conservation Sciences, and Professor Erma Hermens, Director of the Hamilton Kerr Institute and Deputy Director of Conservation and Heritage Science at the Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge. We further thank Cecilia Isaksson, Edith Steen, and Elin Andersson at the National Library in Stockholm; Josefin Bergmark Jimenez and Florian Clerc at Uppsala University Library, and Karin Wretstrand at the Nationalmuseum for their kind assistance during the analyses and their help in characterising the paper and watermarks in the documents. This study received no external funding, with the exception of support from the Nationalmuseum and the Swedish National Heritage Board, who financed the travel of Flavia Fiorillo and Erma Hermens to Stockholm and Uppsala.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.R. initiated this study as part of her research project on Elias Brenner’s colour chart at the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm https://www.nationalmuseum.se/en/pigments-used-in-early-modern-portrait-miniature-painting-in-sweden, aiming to identify the pigments in the colour samples to support her further investigation into the nomenclature. T.S. and M.M. conducted XRF, Raman spectroscopy, and multispectral imaging, while F.F. performed FORS. FTIR and additional Raman spectroscopy were carried out by Anders Nilsson and Erik Bernemalm at Bruker Nordics AB. The authors collaboratively wrote the manuscript, and all have read and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rönnerstam, C., Fiorillo, F., Sandström, T. et al. Rediscovering the colours of Elias Brenner’s pigment nomenclature from 1680. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 417 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01987-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01987-2