Abstract

The tomb of Murong Zhi, a prominent figure of the Tuyuhun Royal Family in the Wuzhou period, represents a significant archaeological discovery in China. Within this tomb, a diverse array of artifacts, including metal ware, wood lacquer items, textiles, and paper relics, have been meticulously unearthed. Noteworthy among these findings is a complete set of stationery, comprising a painted wooden box, writing brush, ink ingot, paper, inkstone, and writing brush holder. This study employs advanced analytical techniques such as SEM-EDS, OM, PLM, Micro-FTIR spectroscopy and Py-GC/MS to investigate the materials and manufacturing processes of these cultural relics. Analysis reveals that the writing brush, crafted from sheep hair, lacks a core, while the ink, bearing inscriptions, is derived from compressed pine wood ash. The distinctive yellow paper is identified to be made from bamboo fibers. This comprehensive examination of the stationery provides valuable physical evidence for understanding Tang Dynasty-era writing materials and techniques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During the transition from the Warring States period to the Han Dynasty, historical artifacts reveal the storage of writing implements, including pens, ink, and other stationery items, within containers made of bamboo or painted boxes. Archaeological excavations at Fenghuang Mountain in Jiangling have uncovered various items such as weights, stone inkstones, brushes, ink, as well as copper and wooden plates stored in bamboo containers1. Similarly, artifacts recovered from the tomb of Jinquishan in the Han Dynasty in Linyi indicate that brushes, inkstones, and other cultural relics were likely housed in bamboo boxes, although deterioration has hindered full restoration efforts, leading to the preservation of stone inkstones in painted lacquer boxes2. Notably, stationery items like brushes were cherished and stored in ornate boxes during this period. However, the early forms of writing tools were diverse, and the standardization of stationery types had not yet been established, resulting in the absence of specialized containers during the Han Dynasty3. With advancements in papermaking technology and the increasing popularity of paper, the quartet of writing and painting supplies-pen, ink, paper, and inkstone-collectively known as the “four treasures of the study,” gained prominence during the Northern Song Dynasty4. Despite this progression, concrete evidence of cultural relics related to the “four treasures of the study” during the Tang Dynasty in China remains elusive, leaving a gap in our understanding of the evolution of writing instruments and practices during this era. Further archaeological investigations and research are necessary to shed light on the presence and usage of these essential tools in Tang Dynasty culture.

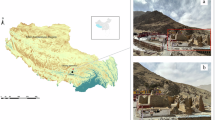

The tomb of Murongzhi stands out as a pivotal archaeological discovery, representing the earliest and most impeccably preserved Tang Tuyuhun royal tomb unearthed in China5. This historical site yielded a plethora of precious artifacts, including gold and silver vessels, painted wood items, leather and silk fabrics, as well as painted pottery. Notably, a fully intact wooden coffin situated on the western side of the tomb chamber was meticulously extracted and transported to the laboratory for further examination. Following meticulous cleaning and excavation procedures, a rich array of burial objects of intricate and varied nature was revealed within. Of particular significance is the presence of a painted wooden box positioned near the right shoulder of the tomb’s occupant, Murongzhi. This box housed two brushes, an ink ingot, two stacks of yellow paper, and a writing brush holder. Remarkably, the lower right half of the box’s tabletop displays distinct ink marks, likely indicating the surface of an inkstone. This bespoke painted wooden box, designed to accommodate writing brushes, ink, paper, and inkstones, represents a rare find in domestic archaeological excavations, underscoring its uniqueness and historical importance. The examination of the stationery unearthed from this tomb not only sheds light on the material culture of the Tuyuhun People but also offers insights into their assimilation into the broader Chinese nation. This investigation provides invaluable data for the scholarly exploration of Tuyuhun royal genealogy, burial customs, and associated themes in later Chinese history. Through a meticulous presentation of these findings, this study aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of the cultural and historical dynamics at play during this transitional period. Hence, we employed a diverse array of cutting-edge scientific methodologies, encompassing microscopic analysis, Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS), Raman spectroscopy, infrared spectrometry, and Pyrolysis Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (Py-GC/MS), to scrutinize the composition of the brush material, ink varieties, paper fiber structures, and delve deeper into the cultural and artistic nuances of the Tang Dynasty. This interdisciplinary approach not only enriches our understanding of the material culture of the era but also unveils the intricate interplay between Tang civilization and the Tuyuhun populace, showcasing the profound impact and cultural amalgamation engendered by the Tang Dynasty. The significance of this research extends beyond mere scientific inquiry; it represents a noteworthy and scarce find in Tuyuhun archaeological studies, offering a gateway to explore the economic and cultural exchanges that transpired with the Tuyuhun community. This discovery not only enriches our comprehension of Tuyuhun history but also provides a unique opportunity to unravel the intricate tapestry of interactions and influences between diverse civilizations during this epoch. Through this meticulous examination, we aim to broaden our insights into the historical trajectory of the Tuyuhun people and their intricate connections with the broader cultural landscape of the Tang Dynasty.

Methods

The stationary contained a stack of writing paper, two writing brushes, ink ingot, and a painted box has been shown in Fig. 1.

A comprehensive analysis was performed on the samples, which consisted of five methods: OM and PLM, SEM-EDS, Micro-FTIR spectroscopy and Py-GC/MS. During the testing process, samples were observed and photographed by a microscope. Paper fiber and surface distribution were observed with OM and PLM. The element compositions of the samples were determined by SEM-EDS. Organic material were identified by the infrared spectrometer and Py-GC/MS. The specific materials and instruments were listed below.

Optical Microscope and polarized light microscope (OM and PLM)

Paper surface reddish pigments which were collected carefully with a scalpel and paper fiber were observed respectively with Leica DM4000M and DM4500P microscope both equipped with Analy SIS Auto digital imaging software at different magnifications (5×, 10×, 20×, 40×, 63×). Zinc-based Herzberg reagent was used to dye paper fiber. The preparation method was as follows according to Li’s research6,7. Zinc chloride (20 g) dissolved in distilled water (10 mL) to form the solution A, and potassium iodide (2.1 g) and iodine (0.1 g) dissolved in distilled water (5 mL) to form the solution B. The supernatant was ready to use after mixing the solution A and B overnight.

SEM (a Quanta 650 of the FEI Company, USA) with EDS (an X-MaxN50 of the Oxford Instruments, UK.) were used for characterizing the elements of the pigment, which was a useful micro-destructive method for analyzing samples of cultural relics. Each sample was put on the sample holder with conductive adhesive and gold sputtering technique was not used in the samples. Aztec software was used in the point & ID mode for micro-analysis. Samples were analyzed with 20 kV acceleration voltage and 10 mm working distance8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15.

Spectroscopy

Infrared spectra were obtained with Thermo Fisher, Nicolet iN10 Mx Fourier transform microscope infrared spectrometer with mercury cadmium telluride (MCT) detector. Two measurement modes were related including attenuated total refection (ATR) mapping and micro transmission with diamond compression cell. The spectrum was composed of 64 scans and ranging from 4000 to 650 cm−1. The spectral resolution was about 4 cm−1 and the spectrum was analyzed with OMNIC Picta software.

The specific organic binding media were further analyzed by Py-GC/MS. The experiment was performed on Agilent, 7890B/5977 A gas chromatography and quadrupole mass spectrometer combined with a Frontier, EGA-PY3030D pyrolyzer. A capillary column HP-5MS (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25μm) was used and the energy of electron ionization was 70 eV. According to the online methylation Py-GC/MS, less than 1 mg of the reddish pigments and 5 μL of 10% methanol TMAH (Aladdin) solution were placed in a sample cup, and then introduced into the pyrolyzer. The derivative reaction was accomplished while pyrolyzed. Pyrolysis temperature was set at 600 °C for 0.2 min while the pyrolyzer interface was set at 300 °C. The chromatographic conditions were: split injection, split ratio 50:1, 1.0 mL/min of Helium (purity 99.995%) as carrier gas and GC injector was held at 300 °C. Initial temperature was 50 °C for 2 min, with a gradient of 4 °C/min up to 280 °C which was kept for 5 min. The mass spectrometer was scanned ranging from 29 to 550 m/z in the full scan mode. The temperatures of MS ion source and MS quadrupole were set at 230 and 150 °C, respectively. Mass spectra of the pyrolysis products were identifed by using the NIST MS library and interpretation of the main fragmentations.

Results

Characteristics of wooden box

The overall shape of the painted wooden box is rectangular, measuring 31.82 cm in length, 17.37 cm in width, and 7.81 cm in height. It is divided into two parts: the cover and the body. The rear part is connected by two hinges, and the front and middle parts are connected by gilded copper buckles and two threads, which are used to thread locking devices. The height of the box cover is 3.41 cm, and the four sides of the top are slanted to form a top. Six copper nails are used to connect the inside and outside of the four corners with silver pieces to wrap the corners. The plate’s height is 4.4 cm, and has a rectangular plate inside, which is one circle smaller in length and width than the four sides of the box. It is 30.74 cm in length and 15.52 cm in width, and is fastened inside the box cover to hold a brush, ink ingot, and paper. The upper part of the long side is vertically inscribed with the character “Wei” in red using a writing brush. The lower part is divided into two parts, with a writing brush holder on the right and a small table on the left. The middle of the tabletop is slightly concave, forming an inkstone surface (Fig. 2.)

The writing brush

There are two writing brushes arranged in a row on the upper right side of the painted wooden box. The writing brush holder is a bamboo tube, with the first one measuring 17.8 cm in length and slightly lighter in color. The upper end is solid and cut from the bamboo joint, while the lower end is cut from the bamboo tube to leave a natural cavity. The edges are slightly polished and trimmed. The second writing brush holder is 17.6 cm in length and slightly darker in color, with a solid core at the upper end. It is speculated that it was cut from the bamboo joint, while the lower end was cut from the bamboo tube to leave a natural cavity. The bristles are inserted into the cavity and buried underground, causing damage and deformation. Depending on the diameter of the writing brush tube, the original appearance of the writing brush tip may be thicker and the protrusion should be moderate. The fur is darker in color, with a dark brown base, a yellowish-brown upper part of the brush, and a black brown tip. Observing from the damaged area of the No.1 brush, the internal fur color of the pen tip is darker and different from the outer bristle color, as shown in Fig. 3.

To further clarify the texture of the writing brush hair material, scanning electron microscopy image, infrared spectra and Py-GC-MS spectrum of the brush hair sample have been further investigated. The results are shown from Figs. 4–7.

From the scanning electron microscope image, it can be seen that the fibers have obvious scales in the longitudinal direction, with a small amount of attachments on the surfaces16,17,18,19,20,21. The cross-section is circular or nearly circular, which conforms to the characteristics of wool fibers22,23.

In addition, as shown in the infrared spectrum, the vibration peak at around 3285 cm-1 is -OH, around 2900 cm-1 is the C-H stretching band, and around 1642, 1530, and 1216 cm-1 are the stretching vibration peaks of amide I, amide II, and amide III, and the results also indicate that it is animal fiber24. Meanwhile, compounds such as toluene has been detected by the analysis of the thermal decomposition gas chromatography-mass spectrometry data (Table 1), indicating the presence of animal-derived components in the sample25,26,27. In addition, there was also Benzofuro[3.2-d]pyrimidin-4(3H-one, Pyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine-1,4 -dione, hexahydro-which were derived from the degradation of collagen. Based on previous studies, combined with infrared spectrum and morphology observations, the hair of the writing brush can be determined to be wool.

Characterization of material of brush handle

Microscopic analysis was conducted on the brush shaft, and after comparing the data, it was found that the spots on Japanese hemp bamboo were most similar to those on unearthed brush shafts (Fig. 8). We speculated that the pen stem material is made of Hu Ma bamboo. In the process of making, tender bamboo with very young bamboo age should be used, which is consistent with the concave shape of the brush shaft (i.e. young bamboo age). This indicates that hemp bamboo has existed in China for thousands of years, and Japan’s hemp bamboo pen production technology should also come from China28.

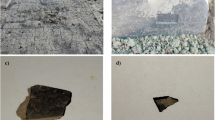

The ink ingot

One ink ingot is placed on the upper left side of the painted wooden tray, with a length of 10.8 cm, a width of 2.0 cm, a thickness of 0.6 cm and a weight of 18.3 g. The ink block is molded into a flat and elongated shape with rounded edges, narrowing at both ends and slightly lifting upwards, with a relatively flat bottom surface, as has been shown in Fig. 9. The lower end is slightly round, and the upper end is slightly flattened after grinding. The front is deeply imprinted, with the four characters “Jin Gu Shang Guang” in Yangwen, vertical style, and a raised sidebar outside the characters.

The results of pyrolysis—gas chromatography—mass spectrometry analysis of ink stick samples are shown in Table 2, Figs. 10 and 11. A series of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and some added adjuvants were detected in the ink stick samples. The polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) detected in the ink stick samples mainly include: Phenanthrene (S1), Fluoranthene (S2), Pyrene (S3), Naphthacene (S4), Triphenylene (S4), Benzo[b]Fluoranthene (S5), benzo[k]Fluoranthene (S5), Perylene (S5), which are respectively marked as S1–S5 for the convenience of representation. Additionally, characteristic combustion compounds from pine-derived materials—α-cedrene, Retene, and Methyl dehydroabietate were identified, along with toluene as a biomarker for animal glue binding. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the sample exhibits characteristic features of pine-soot ink29,30.

According to previous studies, the relative content of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) can be used to distinguish pine-soot ink from lampblack ink. Among them, the most representative is the relative content of S5: S5 has a relatively high relative content in pine-soot, generally higher than 20%, while its content in lampblack is usually lower than 17%. For this reason, we used the selected ion mode (SIM) to test the relative content of the main polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in this sample. After calculation and normalization, the relative content of the main polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the sample is summarized in Table 3.

In this experiment, the relative content of S5 did not exceed 20%; as mentioned before, the relative content of S5 in pine-soot ink is generally higher than 20%. The reasons for this phenomenon may be that the raw materials for making modern pine-soot ink are not entirely pine branches, but also soot formed by burning other trees, or it is made by mixing some oil-soot.

The writing paper

Two layers of writing paper, which are stacked up and down, are placed on the lower part of the upper painted wooden tray, with a yellow brown color (Fig. 12). The overall shape is rectangular, measuring 25 cm in length and 6.5 cm in width. Due to the burial environment, the paper is severely flocculated and cannot be peeled off and unfolded. Consequently, the number of sheets of papers and the folding method are unknown.

After conducting fiber analysis on the writing paper, it was found that thin-walled cells and conduits contained fiber bundles that had not yet dispersed, and some fibers had a small amount of filler on their surfacesv (Fig. 13). It was preliminarily determined to be bamboo fibers31,32,33,34,35.

Therefore, the excavation of paper, brushes, and ink used to write the “Four Treasures of the Study” in this tomb not only enriches and expands the material and cultural materials of the Silk Road, but also provides a more comprehensive understanding of the historical development of ancient writing tools in China and the ethnic relations along the Tang Dynasty and Silk Road. Research on history, papermaking history, material and cultural history, and arts and crafts history also have important value.

Discussion

Research on ancient writing brushes generally believes that the paper-winding method was prevalent in brush-making from the Wei, Jin to the Sui and Tang dynasties. Usually, high-quality animal hairs such as rabbit hair, weasel hair, and goat hair are selected. First, the hairs are classified and sorted, and the parts with appropriate thickness and tough texture are selected, and then the hairs are pasted onto the penholder. The penholder is usually made of materials such as bamboo and wood, and is made smooth, beautiful and easy to hold through processes such as polishing and carving22. The methods of making writing brushes since the Qin and Han dynasties are basically the same as this, and the fundamental difference lies in the method of making the brush head. Judging from the method of making the Tang-dynasty cockerel -spur-shaped brush in the Shosoin Repository, the inside of the brush head is a relatively thick and short paper core made by winding hemp paper. First, a relatively long and thin bunch of hairs is wrapped as the brush tip, and then after winding several circles of hemp paper, a circle of hairs is added, and this is repeated several times until the paper core is as thick as the brush cavity. The outer-wrapped multiple-layer brush hairs are often relatively soft in texture, covering and hiding the paper core36. Except for the cored brushes obtained in this way, all the others seen are core-less brushes. The writing brush unearthed from Murong Zhi’s tomb in the Tang Dynasty is a core-less brush, which provides a great deal of scientific evidence for this understanding. There are relatively many writing brushes unearthed from Tang Dynasty tombs, especially in the Astana ancient tombs in Turpan, Xinjiang, Tang Dynasty tombs near Xi’an, and the Dunhuang area. The shafts of these writing brushes are mostly made of bamboo or wood, and the materials of the brush heads include rabbit hair, weasel hair and sheep hair (goat hair). For example, among the writing brushes unearthed from the Astana ancient tombs, some brush heads are identified as goat hair37.

The evolution of the writing-brush-making techniques can also be attributed to the changes in paper. In ancient times, there were mainly two types of raw materials for paper: plant fibers and animal hides38. Plant fibers mainly included papyrus, bamboo, mulberry bark, hemp, etc. Among them, bamboo-fiber paper, due to its high strength, durability and good writing performance, became an important writing material in ancient times and played an important role in cultural inheritance. In the Tang Dynasty, bamboo-fiber paper was mostly used. This kind of paper had a unique texture and advantages. Bamboo-fiber paper was relatively thin and light, yet tough and not easy to break. Its surface was relatively smooth. Whether for writing or painting, ink could adhere to it very well, and the halo—dyeing effect was just right. At that time, literati and poets were very fond of bamboo—fiber paper, and many well-known calligraphy works and exquisite paintings handed down from ancient times were created on this kind of paper; animal hides were mainly made from the hides of animals such as cattle, sheep, horses, deer, etc.

China has a long-standing history of using ink, which is mainly used for writing, painting and printing. According to the differences in raw materials, it can be roughly divided into two categories: pine-soot ink and lamp-soot ink. Pine-soot ink is made mainly from soot obtained from the incomplete combustion of pine branches rich in pine resin, while lamp-soot ink is made mainly from soot obtained from the incomplete combustion of animal or vegetable oils39,40. Pine-soot ink emerged relatively early in China (during the Qin and Han dynasties). Before that, graphite (mainly composed of manganese oxide) was mainly used, and its technological development laid the basic framework for China’s ink—making process.

In the Tang Dynasty, the ink-making technology was mature, and pine-soot ink and lamp-soot ink were mainly used. Pine-soot ink has a deep color, and lamp—soot ink has a bright luster. There are relatively few ink ingots unearthed from Tang-Dynasty tombs, but ink blocks and ink ingots from the Tang Dynasty were found in the Mogao Caves’ Library Cave. These ink blocks are mostly round or square, with a smooth surface and a hard texture. The ink ingot unearthed from Murong Zhi’s tomb was analyzed and found to be pine—soot ink. It is overall flat and long, with rounded edges, narrowed at both ends and slightly upturned, and has a relatively flat bottom. In the Tang Dynasty, it was popular to inscribe on ink, mainly including the name of the ink—maker, the place of origin of the ink, the chronology and words of praise for the quality of the ink ingot, which reflects the ingenuity of Tang-Dynasty craftsmen. The four characters “Jingu Shangguang” were embossed on the ink ingot unearthed from Murong Zhi’s tomb, which has the same function as the three characters “Songxin Zhen” in intaglio regular script on the ink ingot from a Tang—Dynasty tomb in Turpan, and they are words of praise for the quality of the ink ingot.

The development of the Tang Dynasty culture had a profound impact on the surrounding areas, influencing the development of cultures in other regions to a certain extent, thus promoting cultural exchanges and integrations. The ethnic culture of Tuyuhun was deeply influenced by it. Tuyuhun was originally a branch of the Murong Xianbei in Liaodong. It had a tribal alliance structure internally and was good at actively integrating and accepting people from all ethnic groups and learning from their excellent traditions. From the Northern and Southern Dynasties to the Sui and Tang Dynasties, Tuyuhun had diplomatic exchanges with the Han dynasties and always maintained high—level intermarriage, sending sons and nephews to serve in the court, etc. Therefore, after a long—term process of integration and development and actively accepting Han culture, Tuyuhun had formed a strong cultural identity with the Central Plains civilization. Thus, the stationery unearthed from the tomb of Murong Zhi reflects this characteristic.

Through the preliminary analysis of the Tang Dynasty stationery discovered in the tomb of Murong Zhi, interesting details about the cultural relics of that era are revealed. The brush, characterized as a core-less brush with a moderate edge, offers a valuable reference point for scholars to differentiate between the paper-wrapped pen and the traditional hen pen of the Tang Dynasty. The ink, bearing inscriptions of pine-soot ink, stands as a significant discovery alongside the findings of ink ingots in a Tang Dynasty tomb in Turpan and Tang ink within the Shochangyuan Collection from the Kaiyuan Dynasty in Japan. This revelation enriches our understanding of the shape and decorative symbolism of Tang ink. The yellow mulberry paper found within the tomb provides essential insights into the basic properties of paper used in public and private contexts during the Tang Dynasty, serving as a crucial research foundation. The inkstone and lacquerwood box, crafted as a unified entity with exquisite design, further exemplifies the advanced material culture of the Tang Dynasty. The stationery unearthed from the tomb of Murong Zhi not only reflects the refined material culture of the Tang Dynasty but also serves as a testament to the deep Sinicization of the Tuyuhun royal family and their assimilation into the cultural fabric of the Central Plains dynasty upon their return to Tang rule. The emergence of stationery, as a quintessential material embodiment of Han culture, underscores the profound allure and influence of Han cultural traditions during this period. This discovery not only enriches our understanding of Tang Dynasty material culture but also sheds light on the intricate dynamics of cultural exchange and adaptation that characterized this historical epoch.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

No code were generated or used during the study.

References

Chen, Z. Y. Tomb 168 of the Han Period at Fenghuangshan, Jiangling. Acta Archaeol. Sin. 455–566 (1993).

Shen, Y. Brief Report on the Excavation of the Zhou Family Tombs at Jinque Hill, Linyi, Shandong. Cult. Relics, 41–97 (1984).

Wang, Z. G. & Shao, L. On the shape and related issues of ancient Chinese ink. Southeast Cult. 78–84 (1993).

Zhu, Y. Z. Research on Ancient Chinese Brushes. Nanjing Inst. Arts. 3, 12–18 (2012).

Chen, G. K. et al. Brief report on the excavation of the tomb of Murong Zhi, King of Xihan during the Wu Zhou Period in Gansu. Archaeol. Cult. Relics. 15–38 (2021).

Shi, J. L. & Li, T. Technical investigation of 15th and 19th century Chinese paper currencies: fiber use and pigment identification. J. Raman Spectrosc. 44, 892–898 (2013).

Wei, L. et al. Scientific analysis of Tie Luo, a Qing Dynasty calligraphy artifact in the Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Herit. Sci. 6, 1–14 (2018).

Falcone, F. et al. Innovative methodological approach integrating SEM-EDS and TXRF microanalysis for characterization in materials science: a perspective from cultural heritage studies. Spectrochim. Acta Part B At. Spectrosc. 218, 106980 (2024).

Astolfi, M. L. Advances in Analytical Strategies to Study Cultural Heritage Samples. Molecules 28, 6423 (2023).

Gallagher, W. FTIR analysis of protein structure. Course Manual Chem. 455 (2009).

Derrick, M. R., Stulik, D. & Landry, J. M. Infrared spectroscopy in conservation science. Getty Publications. (2000).

La Russa, M. F. et al. The use of FTIR and micro-FTIR spectroscopy: an example of application to cultural heritage. International Journal of Spectroscopy. 893528 (2009).

Poulin, J., Kearney, M. & Veall, M. A. Direct Inlet Py-GC-MS analysis of cultural heritage materials. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 164, 105506 (2022).

Han, B., Daheur, G. & Sablier, M. Py-GCxGC/MS in cultural heritage studies: an illustration through analytical characterization of traditional East Asian handmade papers. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 122, 458–467 (2016).

Wei, S. Characterization of natural organic binding media used in artworks through GC/MS and Py-GC/MS. Conservation science education online (CSEO)-a heritage science education resource. (2024).

Xing, W. et al. Automatic identification of cashmere and wool fibers based on the morphological features analysis. Micron 128, 102768 (2020).

Allafi, F. et al. Advancements in applications of natural wool fiber. J. Nat. Fibers 19, 497–512 (2022).

Zoccola, M. et al. Analytical methods for the identification and quantitative determination of wool and fine animal fibers: a review. Fibers 11, 67 (2023).

Davies, P. J., Horrocks, A. R. & Miraftab, M. Scanning electron microscopic studies of wool/intumescent char formation. Polym. Int. 49, 1125–1132 (2000).

Wortmann, F. J. et al. Analysis of specialty fiber/wool blends by means of scanning electron microscopy (SEM)[C]//proceedings of the 1st international symposium on speciality animal fibers. 163–188 (1988).

Skals, I. et al. Wool textiles and archaeometry: testing reliability of archaeological wool fibre diameter measurements. Dan. J. Archaeol. 7, 161–179 (2018).

McGregor, B. A., Liu, X. & Wang, X. G. Comparisons of the Fourier Transform Infrared Spectra of cashmere, guard hair, wool and other animal fibres. J. Text. Inst. 109, 813–822 (2018).

Liu, X., et al. FTIR spectrum and dye absorption of cashmere and native fine sheep wool[C]//Proc. 4th Int. Cashmere Determination Techniques Symposium (2008).

Kaiden, K., Matsui, T. & Tanaka, S. A study of the amide III band by FT-IR spectrometry of the secondary structure of albumin, myoglobin, and γ-globulin. Appl. Spectrosc. 41, 180–184 (1987).

Sabatini, F. et al. Investigating the composition and degradation of wool through EGA/MS and Py-GC/MS. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 135, 111–121 (2018).

Han, B. et al. Identification of traditional East Asian handmade papers through the multivariate data analysis of pyrolysis-GC/MS data. Analyst 144, 1230–1244 (2019).

Chiavari, G., Bocchini, P. & Galletti, G. C. Rapid identification of binding media in paintings using simultaneous pyrolysis methylation gas chromatography. Sci. Technol. cultural Herit. 1, 153–158 (1992).

Liao, G. Q. From bamboo brush to bamboo tube pen-bamboo writing tools and Chinese culture. 51–55 (Yunnan Academic Exploration, 1994).

Perruchini, E., Pinault, G. J. & Sablier, M. Exploring the potential of pyrolysis-comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography/mass spectrometry in the characterization of Chinese inks of ancient manuscripts. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 164, 105503 (2022).

Wei, S. et al. Identification of the materials used in an Eastern ** Chinese ink stick. J. Cult. Herit. 13, 448–452 (2012).

Quattrini, M. V. et al. A seventeenth century Japanese painting: scientific identification of materials and techniques. Stud. Conserv. 59, 328–340 (2014).

Luo, Y. et al. Analyzing ancient Chinese handmade Lajian paper exhibiting an orange-red color. Herit. Sci. 7, 1–8 (2019).

Sharma, M., Sharma, C. L. & Lama, D. D. Anatomical and fibre characteristics of some agro waste materials for pulp and paper making. Int. J. Agric. Sci. Res. 5, 155–162 (2015).

Helman-Wazny, A. Fibre analyses of Dunhuang documents in the British Library (2008).

Luo, Y., Wang, Y. & Zhang, X. A combination of techniques to study Chinese traditional Lajian paper. J. Cultural Herit. 38, 75–81 (2019).

Hubei Province Jingsha railway archaeological team Baoshan cemetery arrangement team. Excavation of Chu Tomb in Baoshan, Jingmen City, Cultural Relics, (1988).

Li, X. C., Zheng, B. Q. & Wang, B. Study on ancient paper unearthed from Astana-Harala and Zhuo tombs in Turpan. 62-68 (Western Regions Research, 2012).

Yang, A., Lin, Z. H. & Yi, X. H. Nondestructive identification method of ancient paper fiber composition based on surface microscopic analysis technology. J. Fudan Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 63, 605–615 (2024).

Franke, H. Kulturgeschichtliches über die chinesische Tusche. (Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1962).

Swider, J. R., Hackley, V. A. & Winter, J. Characterization of Chinese ink in size and surface. J. Cult. Herit. 4, 175–186 (2003).

Acknowledgements

We wish to express their sincere gratitude for the financial support received for this study. This work was financially supported by Gansu Provincial Natural Science Foundation ‘Application of Metal Monoatomic-Nanometer Calcium Hydroxide Composites in Mural Painting Conservation’ (No.25JRRA783), Gansu Provincial Cultural Relics Protection Scientific and Technical Research Topics Metal Single-Atom One Nano-Calcium Hydroxide Composites in Mural Painting Protection, Carbon-based Nano-Composites in the Protection of Burial Murals and Gansu Provincial Science and Technology Major Special Project ‘Gansu unearthed organic cultural relics deterioration mechanism and protection technology research’ (No.25ZDFA014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.C. and W.G. designed the experiments, prepared the samples, performed the data analysis and wrote the manuscript. F.H. help write the manuscript. Y.W. and B.L. revised the article. Y.W. performed the experiment and analyse the data. J.M. and Y.C. performed the sectional experiment.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, G., Gu, W., Ma, J. et al. Exploration of stationery items unearthed from the Tomb of Murong Zhi of Tuyuhun in the Tang Dynasty. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 458 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01989-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01989-0