Abstract

Existing research lacks gardens’ holistic spatial pattern analysis, with corridor studies predominantly focus on tangible linear landscapes, neglecting culturally-driven selection approaches. This study analyzes classical gardens of Suzhou (CGS) spatial patterns and corridor construction within its urban fabric. This study utilizes ArcGIS Pro spatial analysis and the minimum cumulative resistance model to construct a hierarchical and categorical heritage corridor for CGS. The study reveals that the corridor exhibits a radial cluster with center-high/edge-low grading, concentrated in the historic urban core, exhibiting strong centrality. Spatial and functional variations exist significantly among corridor types. A “One Corridor-Three Zones-Four Nodes” framework is proposed by integrating their hierarchical and categorical systems. This study constructs a hierarchical and categorical corridor system for CGS, reinforcing the city-garden integration within Suzhou’s urban fabric and offers a replicable conservation-tourism framework.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Classical Gardens of Suzhou (CGS), alongside West Asian and European gardens, constitute the world’s three major gardening systems. Notably, Chinese classical gardens are revered as the “The Primogenitor of Horticultural Civilization”1 and hold a pivotal position in global garden heritage.

The history of CGS can be traced back to the royal gardens of the Wu Kingdom during the Spring and Autumn Period (514 BCE), boasting a history of over 2500 years. Examples include Xiajia Lake, Changzhou Garden, and Hualin Garden, though regrettably, these have long since vanished. Documented records of extensive garden construction began in the Han Dynasty. On one hand, influenced by imperial palace gardens, local officials in Suzhou built gardens within their government offices, giving rise to the unique culture of “agency official gardens.” On the other hand, with the economic development of Suzhou, private gardens gradually emerged, laying the foundation for the later flourishing of CGS. For instance, the early Pijiang Garden2 pioneered techniques such as “gathering stones to store water, planting trees to create streams,” setting a precedent for private gardens in the Jiangnan region. With the introduction of Buddhism in the late Eastern Han Dynasty, Buddhist architecture flourished during the Three Kingdoms and Jin Dynasties. It merged with Suzhou’s local hermit culture, forming a distinctive temple garden system. Consequently, temple gardens thrived in Suzhou, among which Tongxuan Temple, built during the Three Kingdoms period (later renamed Kaiyuan Temple in the Tang Dynasty), still stands today within Panmen, Suzhou(https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E5%BC%80%E5%85%83%E5%AF%BA/2253245).

On the long timeline of history, CGS reached one peak period after another. As noted in Wu Feng Lu (Records of Wu Customs) by Huang Shengzeng, “even common households adorned small artificial hills and miniature islands for enjoyment,” reflecting the widespread popularity of garden-making. Consequently, the number of CGS surged, and their craftsmanship became increasingly refined. Thus, the famous saying, “Gardens in Jiangnan are the finest under heaven, and Suzhou gardens are the finest in Jiangnan,” is by no means an exaggeration.

To this day, Suzhou still boasts an exceptionally rich heritage of classical gardens, earning its reputation as the “City of Gardens.” According to official records from the Suzhou Municipal Bureau of Landscape and Forestry, 108 gardens are currently listed in the Suzhou Garden Inventory (https://ylj.suzhou.gov.cn/szsylj/ylml/nav_list.shtml). In February 2018, the Suzhou Municipal Government further institutionalized this status through the “Implementation Opinions on Accelerating the ‘Heavenly Suzhou: City of Hundred Gardens’ Project” (Document No. Su Fu [2018] 12), formally establishing the “City of Hundred Gardens” initiative(https://ylj.suzhou.gov.cn/szsylj/ylml/nav_list.shtml). The CGS achieved UNESCO World Heritage status in 1997 and 2000, with nine exemplary sites including the Humble Administrator’s Garden, the Lingering Garden, and the Lion Grove Garden being inscribed on the World Heritage List. This recognition has drawn international attention to Suzhou’s garden heritage, fostering globally oriented academic research1. The World Heritage Committee reported that the CGS are exemplary representations of the design philosophy of “creating a microcosm within a limited space”, with their characteristic of “being made by humans, as if created by nature” fully demonstrating the harmonious unity between artificiality and nature3.

In addition, Suzhou’s historic urban district is globally celebrated for its unique “double-chessboard” water-land spatial configuration—a remarkable urban pattern (Fig. 1) that has endured since antiquity. This distinctive urban structure has fostered a highly synergistic relationship between Suzhou’s urban fabric and its CGS. Like strategically placed chess pieces on a board, these gardens occupy key nodes within the crisscrossing transportation network, creating an ideal integration of streets, waterways, and gardens. The poet Chaochu Shen (1649–1702) of the Qing Dynasty vividly captured in his poem “Recalling Jiangnan: Spring Outing”: “Lovely Suzhou - half the city becomes a garden”, perfectly encapsulating the city’s characteristic garden-urban integration4. This intrinsic “city-garden fusion” DNA has persisted throughout Suzhou’s historical development and urban evolution5. Moreover, Suzhou’s abundant heritage resources render the city itself a vast “garden.” Although some waterways and alleys have disappeared due to urban expansion, the ancient city’s fundamental layout, maintained since antiquity, still preserves its essential transportation framework.

Urban pattern (1915) and garden distribution in Suzhou. Photos from “List of Suzhou Gardens”(https://ylj.suzhou.gov.cn/szsylj/ylml/nav_list.shtml), the base map from “Historical maps” (http://www.txlzp.com/ditu/696.html), redrawn by the author.

Although Suzhou boasts numerous classical gardens, both local residents and tourists typically focus only on a few renowned gardens within and around the ancient city, while lesser-known, smaller gardens receive little attention. This phenomenon stems from multiple factors. First, differences in historical significance and fame among the gardens lead to varying levels of publicity, facility maintenance, and activity offerings. Second, disparities in spatial distribution—both in terms of macro-level location and micro-level accessibility—play a role. Gardens situated within Suzhou’s ancient urban core naturally attract more attention than those in peripheral areas. Furthermore, urban road hierarchy adjustments have inadvertently reduced accessibility to some gardens. As a result, the inherent urban characteristic of “city-garden integration” has not been fully utilized. A key challenge lies in coordinating with Suzhou’s existing urban layout to establish stronger spatial connections between famous gardens and lesser-known ones, thereby reinforcing the interdependent relationship between the city and its gardens. As previously mentioned, the causes of this issue are multifaceted. This study, grounded in the historical principle of “city-garden integration,” adopts a holistic perspective to explore ways of enhancing the relationship between the city and its gardens, as well as among the gardens themselves, treating them as an interconnected system for comprehensive research.

The existing research on CGS can be categorized into four categories: historical studies on garden-related figures and literature, studies on garden ontology, research on garden elements, and interpretive studies on garden design techniques. Historical studies focus on prominent figures and works, such as theoretical research on Yuan Ye (The Craft of Gardens)6,7 and investigations into the garden design philosophy of Chen Congzhou (a renowned landscape architect)8,9. Studies on garden ontology encompass both collective analyses of garden groups and individual case studies. Representative works include Classical Gardens of Suzhou10 and The Art of Suzhou Classical Gardens11, which provide comprehensive introductions and analyses of multiple garden cases, along with numerous articles dedicated to individual gardens such as the Net Master’s Garden12,13,14, Humble Administrator’s Garden15,16,17, and Mountain Villa with Embracing Beauty18,19. Research on garden elements involves spatial analysis, landscape assessment, and philosophical interpretations. For example, Liu et al. employed space syntax and statistical methods to examine the spatial organization and socio-spatial logic of CGS20. Sun, Z. investigated the cultural characteristics of classical garden architecture through building layouts and spatial configurations21, whereas Zhou et al. analyzed the humanistic concepts underlying plant landscape design in CGS22. Interpretive studies on garden techniques has focused mainly on applying traditional design approaches to modern architecture. Researchers such as Liu23 and Lu24 have adapted classical garden design principles and spatial strategies in contemporary architectural design. Additionally, some studies integrate garden design philosophy with other disciplines, such as film and television25, classical poetry26, ceramic painting27, and calligraphy art28,29.

Research on CGS tends to emphasize the cultural significance and value of individual gardens, largely in an isolated manner, with few studies adopting a holistic approach. The article “Research on the Brand Value of Suzhou Gardens”30 represents an exception by examining the relationship between CGS and the city itself, proposing the concept of “Suzhou Gardens’ brand value” through an integrated perspective. However, operational methodologies for such holistic research remain underdeveloped. Since the 2005 Xi’an Declaration expanded the connotation of holistic conservation to include the interrelationships between cultural heritage sites, and subsequently the 2008 ICOMOS Charter on Cultural Routes introduced “cultural routes” as a new category of large-scale heritage into the World Heritage List, regional heritage conservation has gradually become a consensus in holistic heritage protection. This approach emphasizes the relationship between heritage and its natural environment as well as its integration with the urban context31.

In terms of holistic heritage conservation approaches, the Historic Urban Landscape theory focuses on the stratigraphic nature and dynamic development of urban heritage. The Cultural Routes concept emerging in Europe connects heritage sites through linear spaces, such as the case study of Via Francigena in Europe32, Case Study of Selected Cultural Routes in Poland33, Cultural Routes of Symi Island in Greece34. Derived from Cultural Routes, the Heritage Corridor approach developed in the United States emphasizes both regional historical-cultural preservation and natural environmental conservation. Cultural Geographic Zoning divides geographical units based on cultural characteristics, typically using dialect regions or cultural spheres as research units for macro-regional pattern analysis.

This study attempts to strengthen the relationships between various gardens and between gardens and the city within Suzhou’s administrative area. Therefore, we propose constructing a CGS Heritage Corridor to integrate lesser-known gardens with classical gardens into a unified heritage corridor system. By connecting these gardens, heritage resources can be collectively protected, ensuring that obscure gardens receive adequate attention. Furthermore, through coordination between the corridor and Suzhou’s urban geographical and spatial patterns, this approach aims to reinforce the city’s inherent characteristic of “city-garden integration.”

The concept of the Heritage Corridor emerged as a product of the concurrent development and interaction among the American Greenway Movement, scenic byway construction, and regional heritage conservation philosophies35. The integration of green corridors and heritage areas not only emphasizes the preservation of regional history and culture along with community economic development, but also maintains the balance of natural ecosystems35. In 1984, U.S. President Ronald Reagan designated the first National Heritage Area—the Illinois and Michigan Canal National Heritage Corridor (https://www.nps.gov/subjects/heritageareas/index.htm). Recognized as America’s first National Heritage Corridor, it exemplifies the corridor’s historical significance (https://www.nps.gov/places/illinois-and-michigan-canal-national-heritage-area.htm), marking the formal establishment of the Heritage Corridor concept.

Most heritage corridor studies follow a top-down macro perspective, focusing on constructing water- and land-based corridors grounded in geographical features, including tangible linear landscapes such as rivers, canyons, mountains, and railways. Representative examples include: the John H. Chafee Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Corridor (https://www.nps.gov/places/blackstone-river-valley-national-heritage-corridor.htm) along the Blackstone River, Ireland’s Westmeath Royal Canal Greenway along the Royal Canal(http://www.westmeathcoco.ie/en/ourservices/artsandrecreation/greenways/royalcanalgreenwaywestmeath/), as well as waterway corridor constructions along Italy’s Lambro River Valley36, the Muzz Canal37 and Lombardy’s historic canals38, China’s Yellow River and Yangtze River basins, Portugal’s Tagus River39, and Germany’s Saale-Unstrut River40. For instance, Tianxin Zhang et al. employed ArcGIS spatial analysis and Minimum Cumulative Resistance (MCR) models to investigate the distribution characteristics of intangible cultural heritage and the suitability of corridor construction in the Yangtze River Economic Belt, proposing corresponding heritage corridor development strategies41. In India, a corridor was created along the Yamuna River connecting the Taj Mahal with Mahtab Garden while linking historical sites along the riverbank42. There are also numerous studies on land-based heritage corridor constructions, including railway heritage43,44, the Silk Road45,46,47, and the Belt and Road48, such as the green island system established along Paris’ Champs-Élysées axis that interconnects significant squares and buildings49.

In contrast, studies on constructing corridors on the basis of point-distributed heritage remain relatively scarce and are still emerging. Examples include China’s porcelain industry heritage50,51, ancient city wall cultural belts52,53, and cultural heritage spatial networks54,55,56. For instance, Konstantina Ntassiou employed Geographic Information System (GIS) tools to identify historical routes in northern Greece and reconstruct the historical road network57. Li, Y. employed GIS to conduct spatiotemporal analysis of 119 grotto temples in Henan Province, examining their evolutionary patterns in relation to geographical and cultural environments58. Lin et al. utilized the MCR method to establish an intangible cultural heritage corridor along the Ming Great Wall52. Similarly, Wang et al. applied both MCR and the gravity model (GM) to construct and evaluate the suitability of a cultural heritage corridor in Tianjin’s historic urban area55. The conceptual scope of heritage corridors continues to expand, evolving from mere vehicles for cultural preservation to critical factors promoting regional economic and social development.

To date, research on heritage corridors has predominantly focused on linear geographical conditions, emphasizing the connecting role of linear elements in integrating heritage sites, which has resulted in relatively mature theoretical frameworks and practical models. This research paradigm heavily relies on the spatial continuity of physical elements while neglecting the intrinsic connections between discretely distributed cultural heritage sites. In comparison, studies on corridor construction based on cultural heritage nodes remain relatively scarce. As an important component of world cultural heritage, constructing heritage corridors on the basis of garden sites expands the conventional linear geographical foundation of heritage corridors, placing greater emphasis on regional cultural characteristics. Simultaneously, establishing heritage corridors for CGS would contribute additional case studies for integrated garden research and reinforce Suzhou’s urban pattern of “city-garden integration.”

Research on heritage corridors has employed various methods and approaches. Historical map and satellite image analysis59,60 compares historical maps with remote sensing imagery to examine temporal changes in heritage landscapes and analyze the evolution of spatial patterns. The MCR model61,62 calculates the least-cost path between target points based on resistance surfaces, simulating optimal corridor routes, which is applicable for heritage corridor identification, connectivity assessment, and cultural diffusion path analysis. The GM55 evaluates spatial relationships and attraction between heritage nodes through their interaction intensity. Circuit theory63,64, based on electrical circuit principles, simulates random walk paths of ecological flows or cultural information across landscapes, identifying critical corridors and barrier areas. The specific characteristics and limitations of these methods are summarized in the following table (Table 1).

This study selects the MCR model for constructing the heritage corridor of CGS based on the following considerations: (1) The research focuses on establishing a corridor system that integrates both natural and cultural elements, rather than merely assessing connection strength between nodes; (2) Compared to circuit theory’s homogeneous diffusion simulation, MCR’s cost-distance path optimization algorithm better reflects optimal connectivity solutions in real environments; (3) The model can integrate multi-source data and incorporate multidimensional factors within a GIS platform. This methodological choice aligns with the spatial characteristics of CGS heritage while meeting practical needs for heritage conservation and management.

This study focuses on CGS as the research object. Based on an understanding of their spatial distribution, this study aims to construct heritage corridors for CGS and conduct hierarchical classification research with the following objectives:

-

1.

Conduct kernel density analysis on CGS to examine the spatial distribution characteristics of garden locations.

-

2.

Construct heritage corridors for CGS and develop a hierarchical classification system. Based on garden accessibility indicators, corridor resistance values, and garden heritage values, this study creates a multilevel heritage corridor classification system, constructing a five-tier system ranging from “primary corridors” to “secondary corridors.”

-

3.

Conduct typological research on the corridors according to garden type distribution, combined with the hierarchical classification system.

-

4.

Perform spatial overlay analysis of the hierarchical and classification systems, ultimately proposing a systematic framework for heritage corridors of CGS.

This work is divided into four sections (Fig. 2). The first section begins with an introduction that provides a concise overview of the CGS, presenting their ideal state of “ city-garden fusion” and highlighting the pressing issues that currently need to be addressed. It systematically reviews the research contents and methodologies of heritage corridors as well as relevant literature on CGS, while presenting this study’s innovations and objectives. The following section details the study area and methodology. The third section presents the final results and findings, offering a comprehensive analysis of gardens’ spatial distribution. It constructs a hierarchical classification system for heritage corridors, proposes a systematic corridor framework, and formulates strategies at macro-, meso-, and micro-levels, while examining the outcomes of forging the “City of Hundred Gardens.” Finally, the key achievements in corridor construction and the study’s novel contributions are summarized, reflects on current methodological approaches, and suggests directions for future research.

Methods

Study area

Suzhou is a national historical and cultural city as approved by the State Council. Located in East China’s Yangtze Delta region, it borders Shanghai to the east, Zhejiang Province to the south, Taihu Lake to the west, and the Yangtze River to the north. Situated in central Yangtze Delta and southeastern Jiangsu Province, its coordinates range from 119°55′ E to 121°20′ E and 30°47′ N to 32°02′ N, covering a total area of 8657.32 square kilometers (https://www.suzhou.gov.cn). In 1997, UNESCO experts visited Suzhou and concluded that its gardens, water networks, and streets give the city unique characteristics65. From 29th October to 2nd November, 2018, the Third Asia-Pacific Conference of the Organization of World Heritage Cities was held in Suzhou, marking the organization’s first official event in China. The conference adopted the “Suzhou Consensus,” and Suzhou was designated as the world’s first World Heritage Model City (https://dfzb.suzhou.gov.cn/dfzb/szdq/202311/577bc9e02a474428b8fce513d7dd3d07.shtml). Suzhou’s urban history dates back to the Spring and Autumn period (770–476 BC). According to historical records, in 514 BC, Wu Zixu, a senior official of the Wu State, was ordered by King Helü to construct Helü city, which established the basic layout of ancient Suzhou. After more than 2500 years of historical evolution, Suzhou’s city walls and scale have remained largely unchanged. The ancient city of Suzhou has completely preserved its dual-chessboard urban spatial structure of “parallel water-land transportation and adjacent canals-streets.”

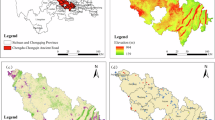

The history of CGS can be traced back to the royal gardens of the Wu Kingdom during the Spring and Autumn Period in the 6th century BC, with a history of more than 2500 years (https://ylj.suzhou.gov.cn/szsylj/ylls/wztt.shtml). Since then, garden construction activities have continued almost without interruption. Private gardens were distributed throughout the ancient city and its surroundings. During the peak period from the 16th to 18th centuries, Suzhou had more than 200 gardens, forming an integrated pattern of “city-garden fusion” where urban gardens and the city area interpenetrated, and the city merged with the surrounding natural landscape66. Since the 21st century, with the municipal government’s strategic measures to promote comprehensive protection and management of CGS, field surveys, verifications, and investigations have been conducted for each garden in the city. Using the “one garden, one record” method for registration, restoration work has been completed for more than one hundred gardens (Fig. 3).

Distribution of classical garden sites in Suzhou city. Drawn by the author, with the base map of China sourced from Standard Map Service System: http://bzdt.ch.mnr.gov.cn/.

Data sources

The data used in this study primarily include the following: (1) Garden heritage site data, comprising coordinate data, and garden types, among others. The coordinate data were obtained using Python from the Baidu Open Map platform (https://api.map.baidu.com/lbsapi/getpoint/index.html), whereas other data were sourced from the official garden registry published by the Suzhou Municipal Bureau of Landscape and Forestry and the Suzhou Forestry Bureau (https://ylj.suzhou.gov.cn/szsylj/ylml/nav_list.shtml, accessed on March 1, 2025). (2) 30-m-resolution DEM and land-use data, obtained from the Geospatial Data Cloud platform of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (https://www.gscloud.cn/#page1). (3) Natural environment data and basic geographic information, including bus and subway station data, Suzhou road traffic data, and OSM vector data of river systems, sourced from the official OSM website (http://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=14/28.1738/112.9396). (4) Administrative boundaries and POI data for public service facilities (e.g., restaurants, hotels, and scenic spots), obtained from Baidu Maps.

Research methods

This study focuses on CGS as the research object. Based on landscape ecology theory and GIS spatial analysis methods, garden heritage corridors were constructed, and systematic hierarchical classification research was conducted. The technical route is shown in Fig. 4 and mainly includes the following five steps:

-

1.

Kernel density estimation (KDE) is employed to analyze the spatial distribution characteristics of CGS and investigate their influencing factors.

-

2.

The MCR model is applied for spatial analysis of the study area to identify and determine optimal zones for constructing garden heritage corridors.

-

3.

Construct a multi-level garden heritage corridor system by applying optimal regional connection algorithm coupled with accessibility analysis.

-

4.

The classification analysis of garden heritage corridors is conducted using both KDE and optimal regional connection tools, integrating with the hierarchical system to identify three major categories and five subcategories of corridor segments.

-

5.

Based on the above analytical results, this study proposes the “City of Hundred Gardens” concept, which progresses from hierarchy to framework, from classification to system, and from isolation to network.

Kernel density estimation (KDE) is a nonparametric spatial statistical method that is primarily used to describe the density of elements within their surrounding neighborhoods67. It quantifies the clustering characteristics of geographic elements in spatial distribution and their density variation patterns. This method generates a continuous spatial density surface by calculating the weighted density value of the element distribution within a certain bandwidth around each spatial location point in the study area. Its mathematical expression is as follows:

A higher KDE value f(x) indicates greater clustering intensity of spatial elements in that region, representing a more concentrated spatial distribution. This method can effectively reveal the heterogeneous characteristics of garden heritage point distributions and their spatial correlation patterns, providing a scientific basis for the quantitative analysis of heritage spatial patterns.

MCR model is a spatial analysis model based on landscape ecology that is used to simulate and quantify the diffusion paths of ecological processes in space and their resistance characteristics68. This method calculates the MCR value of ecological flow diffusion across different landscape units by constructing source targets and spatial resistance surfaces. Its mathematical expression is as follows:

where Dij represents the spatial distance of ecological flow from source i to target j, and Ri represents the resistance coefficient of landscape units to ecological flow. A smaller MCR value indicates higher diffusion efficiency of ecological flow along that path and stronger landscape connectivity. This model can effectively identify potential paths of ecological corridors and their spatial distribution patterns. In this study, the MCR model is used to calculate the MCR experienced by each garden heritage site through different resistance factors and to simulate the optimal paths connecting these garden heritage sites (Fig. 5).

Accessibility is a popular method for measuring transportation performance and essentially represents the ultimate goal of most transportation activities69. In this study, based on the ArcGIS Pro platform, spatial accessibility analysis of garden heritage sites was conducted using a combination of the Generate Near Table tool and the Create Fishnet tool. This method constructs an accessibility evaluation model by calculating the spatial distance or time cost between spatial units and target facility points, quantifying the convenience of service access for each spatial unit. Through the combination of spatial discretization and proximity relationship analysis, this method can effectively reveal the spatial distribution characteristics and accessibility differences within the study area.

Results

Spatial distribution characteristics analysis

The kernel density analysis of CGS (Fig. 6) reveals significant spatial distribution density variations, exhibiting an overall “one core with three sub-centers” agglomeration pattern. The Gusu District forms the high-density core area with a prominent density peak, containing 49% of the total gardens, whereas three secondary density zones emerge in the Wuzhong Taihu Lake District, Wujiang District, and Changshu District.

CGS can be categorized by functional attributes into mansion gardens, temple gardens, agency official gardens, academy gardens, and scenic gardens. This study focuses on three predominant types, mansion gardens, temple gardens, and agency official gardens, which collectively account for more than 85% of the total. Using the KDE tool, we quantitatively analyzed the spatial distribution characteristics of these three garden types, revealing distinct typological differentiation patterns (Fig. 7).

The kernel density analysis results of mansion gardens show that this type of garden exhibits a “large dispersion with small aggregation” spatial distribution pattern. The heritage sites are scattered throughout the city, with high-density areas concentrated in Suzhou’s historic urban district. This is the only garden type demonstrating wide-area distribution characteristics, which is closely related to the widespread dissemination of gentry culture in the Suzhou region. The distribution of temple gardens is primarily clustered in three core areas: Suzhou’s historic urban district, Wuzhong district, and Changshu district. Most are located near hills and waterway transportation nodes, reflecting the spatial coupling relationship between religious activities and commercial trade, as well as certain connections with the “Five Mountains and Ten Temples” monastery system established since the Song Dynasty70. The spatial distribution of agency official gardens is relatively concentrated, and is located mainly in Suzhou’s historic urban district, the Taihu Lake surrounding area in Wuzhong, and the Wujiang district. The distribution of agency official gardens shows high spatial consistency with the establishment of prefectural and county administrative seats.

Construction of heritage corridors for classical gardens of Suzhou based on the MCR model

This study employs 108 classical gardens listed in the Suzhou Garden Directory as heritage source points. Grounded in landscape ecology theory and spatial analysis methods, and incorporating findings from related fields (Table 2), we systematically developed a comprehensive evaluation system comprising 15 resistance factors across three dimensions: natural geographical environment, transportation accessibility, and public service facilities (Fig. 8). The design of resistance factors was based on the following considerations: First, the distribution of CGS is closely related to natural geographical conditions, particularly influenced by land use type, terrain slope, and elevation. Second, these gardens are predominantly clustered along the parallel network of waterways and roads, making transportation accessibility factors—including both waterway channels and land routes—a critical component. Finally, considering their function as public corridors for general use, public service facilities constitute essential elements among the resistance factors, encompassing transportation hubs, metro stations, dining establishments, scenic areas, museums, and hotels.

Among these, the natural geography dimension includes three factors: elevation, slope, and land use type (Fig. 9a–c). Specifically, elevation and slope adopt a negative correlation assignment method, whereby terrain ruggedness exhibits an inverse relationship with resistance values—flatter terrain being more conducive to corridor construction. The land use types were graded and assigned values based on human activity intensity. Since most CGS are located within urban areas and the corridors primarily serve tourists, regions with higher human activity intensity were assigned lower resistance values. Notably, water bodies not utilized as navigation channels were also designated as high-resistance factors. The transportation accessibility dimension comprises waterways, highways, national roads, provincial roads, county roads, and rural roads. The Euclidean Distance algorithm was applied to construct spatial resistance surfaces (Fig. 9d–i), where resistance values exhibit a negative correlation with the distance decay function—that is, areas closer to transportation corridors have lower resistance values. The public service facilities dimension encompasses six types of facilities: transportation hubs, restaurants, scenic spots, subway stations, hotels, and museums. The KDE method was used to construct spatial resistance surfaces (Fig. 9j–o), with facility density values showing a negative correlation with resistance values—meaning that areas with higher concentrations of public service facilities have lower spatial resistance values.

Natural geography includes the distribution of resistance values for (a) elevation, (b) slope, and (c) land use type. Transportation accessibility includes (d) Distance to waterway, (e) Distance to highway, (f) Distance to national road, (g) Distance to provincial road, (h) Distance to county road, and (i) Distance to township road. Public service facilities include (j) Transportation hub, (k) Catering point, (l) Scenic spot, (m) Subway station, (n) Hotel, and (o) Museum.

To scientifically determine the weight allocation of resistance factors for the heritage corridor, this study invited 7 interdisciplinary experts from the fields of cultural heritage, tourism, urban and rural planning, ecology, and landscape architecture. These experts systematically evaluated the weights of each resistance factor on the basis of the spatial distribution characteristics of CGS heritage sites and their current ecological environment status. Through multiple rounds of expert consultation and repeated deliberation, the final weight allocation scheme for each resistance factor was determined (Table 3).Building upon this foundation, the Raster Calculator tool in the ArcGIS platform was employed to perform weighted overlay analysis on the spatial distribution patches of the 14 resistance factors, ultimately generating a comprehensive resistance distribution map of CGS heritage corridor (Fig. 10).

Using the optimal region connection tool in ArcGIS Pro and comprehensive resistance surface data, this study calculated and constructed an optimal connectivity network among garden nodes within the study area. As shown in Fig. 11, the spatial distribution of the ecological corridors in the study area exhibited a distinct radial pattern, extending from the historic urban district of Suzhou to surrounding regions. This corridor system forms a composite network structure, with the historic urban district as the core main corridor and secondary branch corridors including sections in Wuzhong, Wujiang, Luzhi, and Changshu.

Suzhou’s spatial pattern evolved from its unique urban fabric of a “dual chessboard layout of waterways and roads,” where streets and water systems radiate outward from the ancient city center and interweave. The construction of gardens relies on transportation routes and water systems, with most being located at nodes of water and land transportation. This dual chessboard layout also serves as a potential foundation for corridor formation. Moreover, the flat terrain of Suzhou features minimal elevation changes, allowing most areas to follow land and water routes without obstructions, except for hills such as Qionglong Mountain and Tianping Mountain around Taihu Lake in western Wuzhong, which interrupt potential corridor passages. Additionally, as the political, economic, and cultural center of the Jiangnan region since ancient times, Suzhou’s historic urban district has become the core area where garden art flourished71, with most gardens serving as residences for wealthy merchants and literati. The outward radiation of corridors from the ancient city as a concentration area reflects the historical process of garden construction spreading from the center to surrounding areas, as garden culture and architectural techniques disseminated through the movement of merchants, scholars, and craftsmen.

This study conducted accessibility analysis for Suzhou’s garden heritage sites using the Nearest Neighbor Analysis tool in ArcGIS Pro supplemented with the Fishnet tool (Fig. 12). The uniform grid cells generated by the Fishnet tool served as the fundamental analytical units, with grid size significantly influencing computational accuracy. Given the municipal-scale research scope of this study, a 1000 m × 1000 m grid was selected for analysis. Corridor classification was performed based on resistance values (Fig. 13) according to the criteria presented in Table 4. Within the study area, the garden heritage corridors were categorized into five distinct levels(Fig. 14): 1 first-level corridor segment, 2 second-level corridor segments, 4 third-level corridor segments, 4 fourth-level corridor segments, and 5 fifth-level corridor segments (Table 5).

The first-level corridors are mainly distributed in the historical urban area of Suzhou, extending eastward to the Humble Administrator’s Garden, westward to the Lingering Garden, and southward to the Canglang Pavilion, showing significant spatial clustering characteristics and containing 24 garden sites, which form the core framework of the garden heritage corridor system. The second-level corridors connect with the core corridors, extending from the Lingering Garden and Lion Grove Garden to the surrounding ancient city walls, respectively, forming the main trunk corridors of the garden heritage corridor system together with the first-level corridors. The third-level corridors radiate outward around the ancient city, showing obvious directional differences in space: westward to the ruins of Hanshan Bieye Site, where they make an obvious turn due to mountain barriers; southward with two segments - one connecting Fishing Villa and the other turning from Nan Shipiji into Wujiang area to connect with Tuisi Garden; northward to West Garden; and eastward to Baosheng Temple. The fourth-level corridors further extend outward around the third-level corridors, distributed in the suburban areas of Suzhou and connecting corridor nodes such as Dongshan Sculpture Building, Xiancan Temple Garden, and Houlu Garden. The fifth-level corridors, as the terminal of the entire corridor system, wind through various hills in the west, develop along water systems in the south, connect to Changshu area in the north, and link to Kunshan area in the east. The spatial analysis results of the multi-level corridor system demonstrate that the CGS heritage corridor network exhibits distinct “core-periphery” concentric structural characteristics. Specifically, the first- and second-level corridors constitute the main framework of the garden heritage corridor system, while the third- and fourth-level corridors reflect the diffusion directions and pathways of garden culture. The fifth-level corridors complete the integrity of the garden heritage network.

By conducting overlay analysis between garden typology (mansion gardens, temple gardens, and agency official gardens) and the corridor classification system (levels 1–5), the results shown in Fig. 15 were obtained. Based on spatial clustering characteristics, the corridors were categorized into composite corridors, dual-type corridors, and single-type corridors, as presented in Table 6. The composite corridor (Type A) incorporates all three garden types (mansion, temple, and agency official), primarily distributed in Segment 1 of the ancient city’s core area. Dual-type corridors consist of Type B (“mansion + temple”) and Type C (“mansion + agency official”). Type B corridors are mainly distributed in the historic urban core area and along secondary/tertiary corridors in western and eastern regions, as well as fourth/fifth-level corridors in Wuzhong Taihu and Wujiang areas. Type C corridors are concentrated in secondary corridors of eastern and northern Changshu region. The single-type D (“residential only”) exhibits limited quantity and scattered distribution.

a shows the relationship between the kernel density of mansion gardens and corridor classification levels, b shows the relationship between the kernel density of temple gardens and corridor classification levels, c shows the relationship between the kernel density of agency official gardens and corridor classification levels.

From the perspective of garden typology, mansion gardens exhibit a “large dispersion, small clustering” spatial pattern, covering nearly all corridor segments. The temple gardens exhibited significant spatial selectivity and were concentrated in the western and northeastern areas. Agency official gardens are attached to the Suzhou government office with limited distribution. Overall, the core area demonstrated composite characteristics, whereas secondary corridors exhibited functional differentiation. This phenomenon essentially reflects the spatial coupling of political, economic, and cultural functions in the ancient city as the concentrated area for various garden types. The secondary corridors represent different social classes’ spatial preferences, mirroring the urban functional zoning of social activities.

Network construction of heritage corridors for classical gardens of Suzhou

Through the overlay construction of the hierarchical and classification systems for the heritage corridor of the CGS, this study proposes a systematic framework of “one main corridor-three zones-four nodes” (Fig. 16). By systematically connecting isolated garden heritage nodes, a multilevel and multidimensional heritage network is formed.

1. One main corridor: The core area of Suzhou’s historic urban district contains a high concentration of garden heritage sites, displaying significant clustering characteristics of heritage distribution, including numerous World Heritage Sites. It encompasses representative garden masterpieces such as the Humble Administrator’s Garden, Lingering Garden, and Net Master’s Garden, which are organically connected through linear elements, including historic streets and traditional water systems, forming the core framework of the heritage network and providing fundamental support for the entire heritage corridor of CGS.

2. Three zones: First, the Wuzhong and Tiger Hill districts, where the distribution of temple gardens and agency official gardens is most prominent. Among these, the Tiger Hill Mountain Scenic Area serves as the core zone, concentrating representative garden heritage sites such as the Yunyan Temple Pagoda and the ruins of Hanshan Bieye, forming a unique “temple-garden integration” spatial pattern. In the Wuzhong area around Taihu Lake, which is centered on the Taihu National Tourist Resort, garden heritage sites such as the Dongshan Carved Building and Qi garden are distributed along the lake, reflecting the “harmonious coexistence of official and civilian” characteristics of garden culture. The second area is the Wujiang area, which features an interwoven distribution of residential gardens and administrative gardens. With Tongli Ancient Town as its core, garden heritage sites including Retreat and Reflection Garden and Meditation Garden are organically integrated with the ancient town’s urban fabric, demonstrating a “garden-town symbiosis” spatial characteristic. These distinct zones embody the diversity of garden culture. The third is the Changshu district, where the distribution of temple gardens and residential gardens is most prominent. Relying on the landscape patterns of Yu Mountain and Shang Lake, a unique garden landscape system has formed. Temple gardens such as Xingfu Temple were constructed in harmony with the natural scenery of Yu Mountain, embodying the artistic conception of “temples hidden within mountain forests.”

3. Five Nodes: Node 1 is the historic urban core node cluster, centered on World Heritage Sites including Humble Administrator’s Garden, Lingering Garden, and Master-of-Nets Garden within Suzhou’s historic urban area, forming a high-density heritage concentration zone. Node 2 centers on Dongshan Carved Building, which is located in the Wuzhong Taihu Lake rim area, serving as a representative node of Taihu Basin garden culture. Node 3 is centered on Yan Garden in Changshu district, representing a typical example of literati gardens in northeastern Suzhou. Node 4 focuses on the Retreat and Reflection Garden in Wujiang area, serving as a model of Jiangnan water-town ancient settlement gardens.

Discussion

The establishment of the five-tier corridor system reflects the spatial differentiation characteristics of garden heritage. Each tier of corridors assumes distinct roles and functions within the garden heritage conservation network, collectively constituting an integrated protection system. As the principal framework of the garden heritage corridor network, the first-tier and second-tier corridors bear the core conservation functions. They constitute 25% of Suzhou’s total garden inventory and connect most gardens inscribed on the World Heritage List (https://whc.unesco.org/en/about), forming the “primary framework” for garden heritage conservation (Fig. 17). Simultaneously, for comprehensive conservation planning and tourism route planning, the peripheral secondary corridors connected to the primary framework link all garden sites with core garden sites, strengthening their connection with the primary framework area. This promotes the coordinated conservation and development of garden sites across the entire region, establishing a multilevel conservation planning system.

Drawn by the author, photos from “List of Suzhou Gardens.” (https://ylj.suzhou.gov.cn/szsylj/ylml/nav_list.shtml).

This study analyzes the spatial distribution characteristics and formation mechanisms of three major types of CGS - mansion gardens, temple gardens, and agency official gardens. These three garden types exhibit significant differences in spatial distribution, necessitating differentiated protection strategies in conservation practices (Fig. 18):

For mansion gardens, a “multicenter linkage” protection network should be established. The creation of corridor nodes should not be limited to the core historical urban district but should also include protection nodes in major concentration centers such as Wuzhong district, Wujiang district, Changshu city, and Kunshan city. This approach enhances spatial connections between various concentration areas and strengthens systematic protection of this garden type through the construction of garden heritage corridors (Fig. 18a).

For temple gardens, “axial protection” should be emphasized by delineating axial protection zones based on concentration points: an east-west axis connecting the historical urban district with Tiger Hill district and Kunshan district, and a southwest-northeast axis from the historical urban district to Changshu district. By integrating with the garden heritage corridor system, streets and water systems along these axes should be incorporated into the corridor system to enhance spatial continuity. Important temple gardens should be selected as core nodes to generate cultural influence and promote protection and development along the corridors. While forming physical spatial axes, this approach also preserves historical and cultural continuity (Fig. 18b).

For agency official gardens, a “point-to-area” protection model should be adopted, where key nodes drive cultural inheritance and development across the entire region. Key nodes should be identified at kernel density concentration points: the historical urban district concentration, the Wuzhong Taihu Lake rim area concentration, and the Wujiang District concentration. These key nodes should establish key protection zones, fully utilizing the connecting function of garden heritage corridors to network various protection zones and garden sites. Through garden heritage corridors, the cultural influence of key nodes can be expanded to form agency official garden protection zones (Fig. 18c).

Based on the above analysis, this study recommends establishing a garden heritage protection system that progresses “from typological to networked” protection. At the typological protection level, differentiated protection strategies should be formulated according to the spatial characteristics of different garden types: constructing a “multicenter linkage” protection network for residential gardens, implementing “axial protection” for temple gardens, and adopting a “point-to-area” protection model for agency official gardens. At the network connection level, the spatial integration function of the corridor system should be fully utilized to strengthen spatial connections between garden sites and among different garden types through corridor linkages.

At the macro level, the overall structure of the heritage corridor is established, forming a fundamental framework of “one main corridor-three zones-four nodes.” The main corridor, composed of the aforementioned first- and second-level corridors, is situated within Suzhou’s historic urban core and contains well-preserved heritage sites such as the Lion Grove Garden and the Net Master’s Garden. In terms of garden typology, the main corridor comprehensively incorporates mansion gardens, temple gardens, and agency official gardens, creating a cultural exhibition belt that integrates various types of gardens. Building upon the strict protection of garden heritage sites in this zone, characteristic transportation routes and cultural experiences are developed along the heritage corridor, along with the establishment of digital guide platforms, to achieve dynamic heritage transmission.

At the meso level, the “three regions” refer to the Taihu Lake area and Wujiang region dominated by mansion gardens and agency official gardens, as well as the Tiger Hill area characterized by residential gardens and temple gardens. Here, heritage sites coexist with their surrounding environments, local culture, historical connotations, and national spirit. The heritage corridor signifies integrating fragmented and dispersed heritage sites by narrating local stories collectively. Differential regional protection strategies should be formulated based on the typological distribution of garden heritage sites. In the Tiger Hill area, Type B corridors are predominant, forming a distinctive landscape structure of “mountains and temples complementing each other” by leveraging natural mountainous terrain and temple culture. A composite protection mechanism integrating ecology and culture should be established—namely, a trinity of mountain terrain, temple culture, and temple gardens. The construction of heritage corridors can revolve around Buddhist culture, featuring unified interpretive systems and rest points along the route. The Taihu Lake area and Wujiang region are primarily composed of Type C corridors, reflecting the spatial interaction between gentry culture and political power. In constructing heritage corridors, emphasis should be placed not only on the holistic preservation of the region’s water-town landscape but also on enhancing the interpretation of agency official culture. The narrative of garden heritage corridors can be enriched by incorporating agency official ruins, while activities such as recreating scenes of gentry life along the corridor can attract visitors. In summary, each region should develop a systematic cultural narrative framework based on its unique characteristics, linking individual garden sites into coherent cultural stories through heritage corridors.

At the micro level, the focus is on the specific nodes of the corridor, spatial connectivity, and experiential enhancement. Regarding nodes, for well-established heritage sites along the main corridor, such as the Lion Grove Garden and the Net Master’s Garden, the design of visitor routes should be optimized under the strict precondition of preserving their authenticity, thereby enhancing connectivity with other nodes on the corridor and regulating tourist capacity. For smaller, less-protected gardens along the corridor (such as remnant ruins or private gardens), an “acupuncture-style” renewal approach can be adopted—transforming them into “cultural waystations” of the corridor through partial restoration, functional implantation (e.g., teahouses, intangible cultural heritage workshops), or AR-based virtual reconstruction. In terms of spatial connectivity, a dual-path system combining walking and boating should be established along the heritage corridor. While making effective use of historic streets and alleys, efforts should be made to restore ancient canals and tributary routes, with docks constructed to create a waterborne garden tour route.

Under the background of eco-city development, heritage corridor conservation emphasizes organic integration with urban growth.CGS exhibit a high degree of spatial overlap with water systems and other natural ecological elements. The construction of garden heritage corridors must ensure cultural continuity while simultaneously maintaining ecosystem integrity and security. In this study, the development of resistance surfaces effectively avoids ecologically sensitive areas such as forests and water bodies in land-use classification. Furthermore, existing navigable waterways are incorporated into the transportation system to preserve the interconnectedness between gardens and Suzhou’s dual chessboard-style water-land network.

The CGS serve as cultural carriers and distinctive identifiers of the spirit of the city. Their design philosophy of “artificial creation mirroring natural beauty” embodies the profound Chinese philosophical concept of “harmony between man and nature,” whereas their spatial composition of “creating a world within a tiny space” reflects the spiritual pursuits and lifestyle esthetics of Suzhou’s literati. These artistic essences constitute Suzhou’s unique cultural DNA and form the root of urban development. Based on Suzhou’s traditional “dual chessboard” urban planning pattern, the construction of heritage corridors of CGS utilizes the crisscrossing water-land network as a natural spatial foundation, enabling the transformation from isolated garden sites to a networked system. This study proposes a systematic framework of “One main Corridor-Three Zones-Four Nodes”, achieving a paradigm shift from “point-based conservation” to “systematic conservation,” thereby establishing foundations for the “City of Hundred Gardens.”

The systematic framework effectively addresses the issue of scattered garden sites while preserving the ancient city’s layout, significantly expanding the influence radius and service capacity of each garden heritage site and improving their accessibility. Secondly, the corridor construction promotes functional complementarity and coordinated development among garden heritage sites. Through the establishment of a “hierarchical framework” and “typological system,” spatial connections between different grades and types of gardens are realized. The heritage corridor network integrates individual gardens into a unified system, where lesser-known gardens gain exposure through association with classical gardens, thereby increasing the utilization rates of all garden sites. At the operational level, recommendations include implementing a joint garden heritage interpretation system for information sharing, designing thematic tour routes that connect classical and lesser-known gardens, and organizing garden cultural activities to amplify the social impact of garden culture through systematic integration.

The “City of Hundred Gardens” paradigm emphasizes holistic conservation of spatial networks rather than individual site protection, and systematic transmission of cultural values rather than selective preservation. Through the systematic heritage corridor framework of “One main Corridor-Three Zones-Four Nodes,” the transformation “from gardens to city” is achieved.

The heritage corridor system of CGS constructed based on the “One corridor-Three zones-Four nodes” framework, exhibits a high degree of coupling with Suzhou’s urban spatial pattern, historical context, and landscape ecology, demonstrating a unique adaptability distinct from other historical and cultural cities. First, it aligns with Suzhou’s urban spatial structure. Relying on the city’s “dual chessboard of waterways and roads” texture, it forms a dispersed distribution pattern radiating outward from the ancient city center. This results in the formation of the “One main corridor” at the aggregation point within the ancient city. Second, it matches cultural functions. The “Three zones,” constructed through different cultural themes, effectively correspond to the distribution characteristics of functionally diverse gardens within Suzhou. Third, based on the clustering features of the gardens and leveraging the street networks and waterways of Suzhou, “cultural waystations” are established for the corridor. Compared to other historical and cultural cities like Hangzhou and Yangzhou, this study, grounded in the cultural logic of gardens and relying on Suzhou’s urban structure, integrates scattered garden heritage into a narrative-driven display system. This approach transcends the individual value of single gardens, forming a holistic cultural landscape system.

This study applies the well-established theoretical model (MCR) from ecological corridor research to the study of garden heritage corridors. In the field of heritage corridor research, existing literature predominantly focuses on linear corridor construction based on geographical conditions. This study, however, moves beyond geographically constrained route selection by incorporating regional characteristics and cultural contexts to develop more precise and contextually appropriate corridor planning. Furthermore, classification studies on heritage corridors remain relatively scarce72. Through hierarchical and typological research on garden heritage corridors, this paper attempts to propose a systematic, multi-level, and regionally differentiated conservation framework. While current research on individual gardens has reached a relatively mature stage, this study breaks through the limitation of most existing literature that examines gardens in isolation. Instead, it treats gardens as organic components of urban systems. This approach reveals the interactive relationship between CGS and ancient urban spatial structures while exploring the underlying influencing factors. Through the construction of heritage corridors and the analysis of hierarchical and typological systems, this study proposes a systematic framework—“one main corridor-three regions-four nodes”—establishing a multi-level and multi-dimensional garden heritage framework that reinforces Suzhou’s historical urban layout.

Like other studies, this research has limitations in its analytical methods. Different recreational behavior preferences of people in urban environments exhibit distinct spatial characteristics73. While it is possible to conduct quantitative analysis of resistance factors using natural features, land use, and commercial points, quantifying people’s perceptions of different garden sites remains challenging. Moreover, given the indispensability of the internet in daily life, group perceptions are rapidly and widely disseminated through online media via “check-in” notes, reviews, or travelogues, making the impact of such social semantic factors nonnegligible. To address these research limitations, future studies should focus on the following areas for further development: developing perception analysis methods based on big data, integrating multisource data such as social media data and mobile positioning data, and establishing quantitative indicator systems for social semantic factors.

This study employs the MCR model to construct a heritage corridor of CGS, followed by corridor classification and hierarchical classification. The results indicate the following:

-

1.

The heritage corridors of CGS exhibit a highly centralized, distinctly radial pattern. Radiating outward from the historic urban core of Suzhou, these corridors extend along the city’s major water systems and traditional streets, demonstrating spatial congruence with Suzhou’s “dual chessboard” urban fabric. This spatial configuration reflects the interactive relationship between garden construction and urban expansion throughout historical development.

-

2.

The corridor hierarchy displays a center-high, periphery-low distribution pattern, with core corridors concentrated in Suzhou’s historic urban district, showing marked centrality characteristics. This multilevel distribution profoundly reflects the historical trajectory and spatial logic of Suzhou’s urban development.

-

3.

Corridor classification reveals significant typological differentiation. Certain garden heritage types cluster in specific areas of Suzhou, whereas others are widely distributed across the entire urban region. This typological variation reflects the close relationship between different gardens’ historical functions and spatial locations, providing crucial basis for formulating category-specific conservation strategies.

-

4.

The overlay of hierarchical and typological corridor results reveals distinct stratified characteristics of the main corridor-zone -node. This spatial structural feature provides an important theoretical foundation for constructing systematic conservation frameworks.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Chen, D., Wang, C., Jiang, Z. & Zhou, S. Research on brand value of Suzhou gardens. Zhongguo Yuanlin (Chin. Landsc. Archit.) 34, 35–39 (2018).

Shen, H. World cultural heritage: Suzhou classical gardens. Dang’ yu Jianshe (Arch. Constr.) 2004, 27–29+32 (2004).

Cao, L. Chinese cultural ‘natural history’: a brief discussion of architectural decoration patterns in Suzhou gardens. Suzhou Univ. J. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2007, 95–100 (2007).

Zhang, T. & Lian, Z. Research on the distribution and scale evolution of Suzhou gardens under the urbanization process from the Tang to the Qing dynasty. Land 10, 281 (2021).

Peng, Y. Research on the evolution and inheritance of Suzhou urban form from the perspective of morphological genes. In Beautiful China, Co-Construction, Co-Governance and Sharing: Proc. 2024 China Urban Planning Annual Conference (10 Urban Cultural Heritage Conservation) (eds China Social Urban Planning & Hefei Municipal People’s Government) 1791–1800 (School Architecture at Huaqiao University, 2024).

Liu, Y., Wu, G. & Feng, T. Discussion on the organization of water management discourse in Yuan Ye from the perspective of mountain-water significance. Zhongguo Yuanlin (Chin. Landsc. Archit.) 37, 139–144 (2021).

Yin, S. & Du, Y. Inspiring mind with context and creating scenery according to context: the fundamental design thinking of Yuan Ye. Zhongguo Yuanlin (Chin. Landsc. Archit.) 28, 85–87 (2012).

Zhu, Y. The “concept of qi-gu” in Zhe School: an alternative interpretation of Chen Congzhou’s landscape design philosophy. Zhongguo Yuanlin (Chin. Landsc. Archit.) 34, 61–63 (2018).

Duan, J. & Liu, Z. The contemporaneity of Chen Congzhou’s garden construction: framework establishment and connotation analysis. Fengjing Yuanlin (Landsc. Archit.) 31, 73–80 (2024).

Liu, D. Classical Gardens of Suzhou (China Architecture & Building Press, 1979).

Shao, Z. The Art of Suzhou Classical Gardens (China Forestry Publishing House, 2001).

Liu, Q. & Zhu, J. Study on the proportional relationship between gray space and external space in the Master-of-Nets Garden. Zhongguo Yuanlin (Chin. Landsc. Archit.) 30, 103–107 (2014).

Pang, Z. & Li, W. Analysis of layout, greening and landscape in the Master-of-Nets Garden. Jianzhu Xuebao (Archit. J.) 1980, 13-15+65-5 (1980).

Zhang, T. et al. The generation mechanism of temporal-spatial perception of ‘scenes changing with steps’ in the Master-of-Nets Garden. Zhongguo Yuanlin (Chin. Landsc. Archit.) 39, 22–28 (2023).

Chen, H. & Li, Y. Analysis of narrative space in the Chinese classical garden based on narratology and space syntax—taking the Humble Administrator’s Garden as an example. Sustainability 15, 12232 (2023).

Ji, Y., Qin, R. & Huang, S. Contemplation and perspective of literati landscape garden: a panoramic reconstruction based on Thirty-one Scenes of the Humble Administrator’s Garden. Zhongguo Yuanlin (Chin. Landsc. Archit.) 32, 87–93 (2016).

Wei, S. & Liu, H. Quantitative research on spatial characteristics of landscape elements in the Humble Administrator’s Garden. Zhongguo Yuanlin (Chin. Landsc. Archit.) 31, 78–82 (2015).

Meng, F. Study on the rockery design techniques of the Mountain Villa with Embracing Beauty. Zhongguo Yuanlin (Chin. Landsc. Archit.) 36, 133–138 (2020).

Ding, M. et al. Fractal quantitative study on contour lines of rockery combination elements in the Mountain Villa with Embracing Beauty. Zhongguo Yuanlin (Chin. Landsc. Archit.) 37, 128–132 (2021).

Liu, K. et al. Interpreting the space characteristics of everyday heritage gardens of Suzhou, China, through a space syntax approach. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 1–26 (2024).

Sun, Z. “Thought and environment in harmony”: On the cultural aesthetic characteristics of Chinese classical garden architecture space. Zhonghua Wenhua Luntan (Forum Chin. Cult.) 2016, 79–83 (2016).

Zhou, J. & Huang, Y. On the humanistic thoughts in plant landscape design of Suzhou gardens. Zhuangshi (Art. Des.) 2006, 126–127 (2006).

Liu, K. Landscape architecture practice under classical garden design principles: Jiande Fuchun New Century Resort project. Zhongguo Yuanlin (Chin. Landsc. Archit.) 39, 6–10 (2023).

Lu, J. et al. Space creation based on Suzhou classical gardens: reconstruction of Wan Residence at No.7 Wangximaxiang Lane, Suzhou. Jianzhu Xuebao (Archit. J.) 2013, 100–103 (2013).

Zong, C. & Zhou, X. Analysis of Gu Chun’s paper garden creation and garden practice as the author of Hongloumeng Ying. Zhongguo Yuanlin (Chin. Landsc. Archit.) 40, 134–138 (2024).

Hu, W. The garden thought in Tao Yuanming’s poems: analysis of the characteristics of “Yuantianju” from the perspective of garden construction. Zhongnan Minzu Daxue Xuebao (J. South-Cent. Minzu Univ. Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 42, 144–151+187 (2022).

Liu, L. & Zhang, W. The reference model of Kangxi five-color porcelain to Ming and Qing woodblock prints: taking “garden” images as examples. Taoci Xuebao (J. Ceram.) 39, 498–502 (2018).

Song, Z., Jiang, H. & Cui, T. Exploring the correlation of space creation in Suzhou classical gardens and the Chinese calligraphy Yan Zhenqing’s three manuscripts. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 1–23 (2024).

Ni, F. The influence of Chinese calligraphy and painting art on the aesthetic connotation of classical gardens. Meishu Yanjiu (Art. Res.) 2014, 105–108 (2014).

Chen, D. L. et al. Study on the brand value of Suzhou classical gardens. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 34, 35–39 (2018).

Li, T. Spatial distribution characteristics and holistic conservation of historical and cultural resources in Weinan City. Xi’an Univ. Archit. Technol. https://doi.org/10.27393/d.cnki.gxazu.2024.000164 (2024).

Splendiani, S., Forlani, F., Picciotti, A. & Presenza, A. Social Innovation project and tourism lifestyle entrepreneurship to revitalize the marginal areas. The case of the Via Francigena cultural route. Tour. Plan. Dev. 20, 938–954 (2023).

Bogacz-Wojtanowska, E., Góral, A. & Bugdol, M. The role of trust in sustainable heritage management networks. Case study of selected cultural routes in Poland. Sustainability 11, 2844 (2019).

Fafouti, A. E. et al. Designing cultural routes as a tool of responsible tourism and sustainable local development in isolated and less developed islands: the case of Symi Island in Greece. Land 12, 1590 (2023).

Wang, J. & Li, F. Literature review of linear heritage at home and abroad. Dongnan Wenhua (Southeast Cult.) 2016, 31–38 (2016).

Toccolini, A., Fumagalli, N. & Senes, G. Greenways planning in Italy: the Lambro River Valley greenways system. Landsc. Urban Plan. 76, 98–111 (2006).

Dal Sasso, P. & Ottolino, M. A. Greenway in Italy: examples of projects and implementation. J. Agric. Eng. 42, 29–40 (2012).

Fumagalli, N. & Toccolini, A. Relationship between greenways and ecological network: a case study in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. 6, 903–916 (2012).

Oliveira, R. Planning the Green Infrastructure of the Tagus River Estuary in Lisbon Metropolitan Area, Portugal. In Proc. 5th Fábos Conference on Landscape and Greenway Planning, Budapest, Hungary, (eds University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries) 183–190 (2016).

Hoppert, M. et al. The Saale-Unstrut cultural landscape corridor. Environ. Earth Sci. 77, 58 (2018).

Zhang, T., Yang, Y., Fan, X. & Ou, S. Corridors construction and development strategies for intangible cultural heritage: a study about the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Sustainability 15, 13449 (2023).

Harkness, T. & Sinha, A. Taj heritage corridor: intersections between history and culture on the Yamuna riverfront (places/projects). Places 16, 62–69 (2004).

Chasco, F. R. & Meneses, A. S. Project for a greenway on the Vasco-Navarro railway. In Proc. 13th International Congress on Project Engineering, Badajoz, Spain, (eds Asociación Española de Ingeniería de Proyectos (AEIPRO)) 155–166 (2009).

Li, X. & Xia, H. Research on the regenerative value evaluation of railway heritage corridors: a case study of Jingzhang Railway (Beijing section). Nanfang Jianzhu (South Archit.) 2023, 40–51 (2023).

Shen, Y. et al. Reconstructing the Silk Road Network: insights from spatiotemporal patterning of UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Land 13, 1401 (2024).

Kurdoglu, O. & Kurdoglu, B. C. Determining recreational, scenic, and historical-cultural potentials of landscape features along a segment of the ancient Silk Road using factor analyzing. Environ. Monit. Assess. 170, 99–116 (2010).

Wang, Y. & Zeng, G. Research on the construction of Silk Road cultural heritage corridor from a spatial perspective: A case study of Gansu section. Shijie Dili Yanjiu (World Reg. Stud.) 31, 862–871 (2022).

Li, H. et al. Research on ecotourism carrying capacity of “Belt and Road” heritage corridors based on state-space model. Zhongguo Yuanlin (Chin. Landsc. Archit.) 36, 18–23 (2020).

Pourjafar, M. & Moradi, A. Explaining design dimensions of ecological greenways. Open J. Ecol. 5, 66–79 (2015).

He, D., Wang, Z. & Wu, H. Research on the construction of Jingdezhen porcelain heritage corridor system based on MCR and MCA models. Dili yu Dili Xinxi Kexue (Geogr. Geo-Inf. Sci.) 38, 74–82 (2022).

Zhan, J. Research on tourism resources of Jingdezhen ceramic heritage corridor. Taoci Xuebao (J. Ceram.) 35, 542–547 (2014).

Lin, F., Zhang, X., Ma, Z. & Zhang, Y. Spatial structure and corridor construction of intangible cultural heritage: a case study of the Ming Great Wall. Land 11, 1478 (2022).

Wang, Y. & Wang, H. Quantitative evaluation of heritage resources along Nanjing Ming City Wall corridor based on AHP method. Nanjing Linye Daxue Xuebao. (J. Nanjing. Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed.) 39, 95–100 (2015).

Wu, Y. et al. The research on the construction of traditional village heritage corridors in the Taihu Lake region based on the current effective conductance (CEC) theory. Buildings 15, 472 (2025).

Wang, Q., Yang, C., Wang, J. & Tan, L. Tourism in historic urban areas: construction of cultural heritage corridor based on minimum cumulative resistance and gravity model—a case study of Tianjin, China. Buildings 14, 2144 (2024).

Zhang, J., Jiang, L., Wang, X., Chen, Z. & Xu, S. A study on the spatiotemporal aggregation and corridor distribution characteristics of cultural heritage: the case of Fuzhou, China. Buildings 14, 121 (2024).

Rudan, E., Madžar, D. & Zubović, V. New challenges to managing cultural routes: the visitor perspective. Sustainability 16, 7164 (2024).

Li, Y. Analysis of the relationship between the temporal and spatial evolution of Henan grotto temples and their geographical and cultural environment based on GIS. Herit. Sci. 11, 216 (2023).

Loren-Méndez, M. et al. Mapping heritage: geospatial online databases of historic roads. The case of the N-340 roadway corridor on the Spanish Mediterranean. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 7, 134 (2018).

Lv, R. et al. Urban historic heritage buffer zone delineation: the case of Shedian. Herit. Sci. 10, 64 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Research on the construction of intangible cultural heritage corridors in the Yellow River Basin based on geographic information system (GIS) technology and the minimum cumulative resistance (MCR) model. Herit. Sci. 12, 271 (2024).

Yue, F. et al. A framework for the construction of a heritage corridor system: a case study of the Shu road in China. Remote Sens. 15, 4650 (2023).

Wu, Y. et al. Study on spatial distribution and heritage corridor network of traditional settlements in ancient Huizhou. Buildings 15, 1641 (2025).

Wang, Y., Zhang, L. & Song, Y. Study on the construction of the ecological security pattern of the Lancang River Basin (Yunnan Section) based on InVEST-MSPA-circuit theory. Sustainability 15, 477 (2023).

Wang, Y., Wu, W. & Boelens, L. City profile: Suzhou, China—the interaction of water and city. Cities 112, 103119 (2021).

Duan, J. et al. The connotation and mechanism of spatial gene. Chengshi Guihua (City Plan. Rev.) 46, 7–14+80 (2022).

Samet, H. Applications of Spatial Data Structures: Computer Graphics, Image Processing, and GIS (Addison-Wesley, 1990).

Yu, K. et al. Discussion on suitability analysis method of heritage corridor in rapid urbanization area: a case study of Taizhou City. Dili Yanjiu (Geogr. Res.) 2005, 69–76+162 (2005).

Dixit, M. & Sivakumar, A. Capturing the impact of individual characteristics on transport accessibility and equity analysis. Transp. Res. Part D. Transp. Environ. 87, 102473 (2020).

Liu, C. D. Study on the temple system of Five Mountains and Ten Temples in Song Dynasty. Relig. Stud. 2004, 105–113+195 (2004).

Tu, X., Pu, L. & Zhu, M. Comprehensive regional land quality evaluation based on extension theory and coordination analysis.Nongye Gongcheng Xuebao (Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng.) 2008(11), 57-62 (2008).

Zhang, H., et al. Assessment of Yellow River Region Cultural Heritage Value and Corridor Construction across Urban Scales: A Case Study in Shaanxi, China. Sustainability 16, 1004 (2024).

Zhou, X., Tang, Y. & Su, J. A heritage corridor route selection method based on historic urban landscape and digital footprint perspectives: A case study of Nanjing historic urban area, China. Landsc. Archit. Front. 11(3), 11-37 (2023).

Feng, B. & Li, W. Study on Historic Urban Landscape Corridor Identification and an Evaluation of Their Centrality: The Case of the Dunhuang Oasis Area in China. Land 14, 585 (2025).

Sun, Y., et al. Large-scale cultural heritage conservation and utilization based on cultural ecology corridors: a case study of the Dongjiang-Hanjiang River Basin in Guangdong, China. Herit. Sci. 12, 44 (2024).

Du, C., Pan, D. & Liu, Q. The Construction of a Protection Network for Traditional Settlements Across Regions: A Case Study of the Chengdu-Chongqing Ancient Post Road Heritage Corridor in China. Land 14, 327 (2025).

Teng, Y. B. Construction of heritage corridor network of Xiahe ancient road based on minimum resistance model. Planners 36, 66-70 (2020).

Ye, H., Yang, Z. & Xu, X. Ecological Corridors Analysis Based on MSPA and MCR Model-A Case Study of the Tomur World Natural Heritage Region. Sustainability 12, 959 (2020).

Du, Y. F., et al. Research on the spatial construction of heritage corridors in the Yellow River Basin from a watershed perspective. Cult. Relics Museol. 2024, 103-112 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by: National Key R&D Program of China “Strategic Scientific and Technological Innovation Cooperation” Key Special Project: “China-Portugal ‘Belt and Road’ Joint Laboratory for Cultural Heritage Conservation Science: Establishment and Collaborative Research” (2021YFE0200100). 2025 Jiangsu International Science and Technology Cooperation/Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan Science and Technology Cooperation Program—“Belt and Road” Innovation Cooperation Project: “Collaborative R&D on Key Technologies and Materials for Climate-Adaptive Conservation of Sino-Portuguese Architectural Heritage Under Climate Change”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W. conceived the research topic designed the study framework. Y.J. wrote the main manuscript text and prepared figures. Y.W. provided valuable suggestions for the introduction and discussion sections. M.M. offered guidance on the methodology. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions