Abstract

Paper has become the world’s predominant writing medium since its invention. However, non-paper writing materials have also played a significant role in human civilization, serving purposes beyond mere text transmission. Despite their importance, research about craftmanship and utilization of these alternative materials remain limited. In this study, we employed non-destructive and micro-destructive analytical techniques—including THM-Py-GC/MS, p-XRF, ATR-FTIR, and hyperspectral imaging (HIS) to examine fragments excavated from Taklung Monastery in Tibet. Results identified birch bark as the writing material and revealed that ink was prominently gold (Au). This discovery reports a rare case of the utilization of gold ink on birch bark, offering valuable insights into 13th-century Tibetan writing material production. Furthermore, HIS enabled text extraction from the fragments. Combined with the unique excavation context, we suggest that birch bark also possesses religious significance. This study enhances our understanding of the diverse applications of writing materials of ancient Tibet.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Manuscript materials have played an irreplaceable role in the dissemination of human civilization. Since its formal invention during the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 AD), paper has gradually become the most widely used writing medium worldwide. However, even before the advent of paper, a variety of writing materials existed, including organic substrates such as bark, leaves, silk, sheepskin, donkey hide, and wooden tablets, as well as inorganic materials such as clay tablets, gold, silver, bronze plates, and stone slabs1. These materials also served as crucial vehicles for information transmission and exchange, significantly contributing to the formation and advancement of early human civilizations. Among them, writing materials such as palm leaves manuscripts and birch bark were extensively used in northwestern India and Kashmir until the Mughal Empire (1526–1857 AD), when they were gradually replaced by paper2,3. Even today, certain religious scriptures continue to be written on these materials, indicating that non-paper manuscripts held an essential and enduring role in ancient societies, serving not only as text carriers but also fulfilling diverse functional and symbolic purposes.

The Tang-Tubo Road and the Tubo-Nepal Road, as branches of the Silk Road across the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, served as vital corridors connecting central China with China Tibet, Nepal, and India since the Tang Dynasty (618–907 AD), facilitating trade, religious transmission, and tributary exchanges4. The Old Book of Tang (Jiu Tang Shu 舊唐書), the earliest systematic historical record of the Tang Dynasty, contains detailed accounts of political figures, legal systems, major events, and foreign affairs, making it an essential primary source for Tang historiography. A notable passage states: “Tubo (633-842 AD, represents the Tibetan regime in ancient China), requested silkworm eggs, as well as artisans skilled in brewing, milling, papermaking, and ink production, all of which were granted”. This indicates that papermaking technology had been introduced into Tubo by at least 650 AD. Lhasa, as a key hub along the Tang-Tubo and Tubo-Nepal routes, became a center of cultural and technological exchange. With the spread of papermaking, paper production rapidly expanded across Tubo, particularly in Lhasa and Shannan city5. Numerous studies have been applied on the materials6,7,8,9,10, pigments, and writing media11,12, as well as crafts13 of Tibetan manuscripts across different periods, laying a foundation for understanding the development of manuscript craftsmanship of ancient Tibetans.

However, due to geographical constraints and limited transportation, external materials were rarely accessible to Qinghai-Tibet Plateau in large quantities. Before the introduction of paper, local communities utilized various alternative writing substrates, including bark, wooden tablets, and bamboo slips5. Even after the adoption of paper, materials such as palm leaves and birch bark remained in widespread use for Buddhist scripture transcription. Understanding how these multi-material manuscripts were produced and utilized is key to reconstructing Tibetan manuscript production system. Yet, research in this area remains scarce, highlighting an urgent need for further investigation.

In 2023, during the restoration of a stupa at Taklung Monastery in Lhundrup County, Lhasa, Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR), two fragmentary bark-like pieces bearing inscriptions were discovered. These samples provide rare and valuable material evidence for studying the utilization and production techniques of historical Tibetan manuscripts. This study employs non-destructive and minimally invasive analytical methods, including Thermally assisted Hydrolysis and Methylation Pyrolysis-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (THM-Py-GC/MS) and Attenuated Total Reflection Flourier Transformed Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR), to identify the material composition of the manuscript fragments. Additionally, hyperspectral imaging (HSI) and portable X-ray fluorescence (p-XRF) are utilized to recover textual content and characterize the ink. These findings offer new insights into the diverse material applications and craftsmanship of historical Tibetan manuscripts.

Methods

Site and sample information

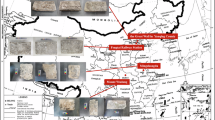

Taklung Monastery is located in Lhasa, TAR (Fig. 1). As a principal monastery of the Kagyu Sect of Tibetan Buddhism, it holds significant religious and historical importance. Founded in 1180 AD, the monastery became a center for Buddhist teachings, attracting disciples and establishing the Taklung Kagyu lineage, which remains influential within Tibetan Buddhism.

The monastery complex covers an irregularly shaped area of approximately 87,500 m², with monastic quarters in the northern section and temple structures in the southern section. The manuscript samples were excavated from the ruins of ChoKhang Marbo (the red temple) (Fig. 1b) within the monastery, which underwent archaeological investigation between April and June 2023. The site yielded a variety of artifacts, including statues of diverse materials, ritual conch shells, stupas, fragmented ancient texts, religious implements, and Tsha-tshas. Tsha-tshas are small, molded clay votive tablets depicting Buddhas or stupas, regarded in Tibetan Buddhism as sacred objects for dispelling misfortune and invoking blessings.

The two manuscript fragments (sample number was designated as XZDL-1 and XZDL-2, respectively) were originally folded and embedded within a tsha-tsha, placed inside a statue (Fig. 2). These samples provide critical material evidence for studying the craftmanship and utilization diversity of Tibetan manuscripts.

Radiocarbon dating

A small fragment (~1 mg) from sample XZDL-1 was submitted to the Chronology Laboratory of Lanzhou University for radiocarbon dating. Accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) was performed using a MICADAS system, and the age result was calibrated using OxCal v4.4 with the IntCal 20 atmospheric curve.

Sample observation and imaging

Length, width, and thickness of the fragments were measured using a digital caliper. Surface morphology was examined under a Leica S9D stereomicroscope. Macroscopic images were captured with a Nikon D610 camera. To improve the readability of faded text, a handheld hyperspectral imager (SPECIM-IQ) was applied for data acquisition, followed by processing with a multispectral imaging system (Nuance EX, Cambridge Research & Instrumentation, Inc. (Cri).

The multispectral images were tested using VNIR visible near-infrared band range from 450 to 720 nm with a spectral sampling of 10 nm. The ink and blank area spectra were selected as endmembers from the images, and the hyperspectral images were unmixed through the unmixing module accompanying Nuance EX. Fifteen images were taken for each of the two fragments separately, after which the images were spliced by PS 2018 software.

Thermally assisted hydrolysis and methylation pyrolysis–gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (THM-Py-GC/MS)

Samples were taken from blank areas with a mass of about 0.5 mg. Subsequently, they were placed in the sample cup. Derivatization was performed by adding 2 μL of 25% tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH) in methanol to the cup. Then, put the sample cup into the pyrolyzer (PY3030D, Frontierlab) for pyrolysis with a temperature of 500 °C. GC/MS instrument model was QP2030 NX, Shimadzu; inlet temperature was set at 300 °C in GC; samples were transferred by split injection technique, with a ratio of 20:1; the temperature program for the column was set as follows: initially maintained at 40 °C for 3 min, then increased to 350 °C at a rate of 10 °C per minute, and finally held at 350 °C for 5 min. Helium was utilized as carrier gas with a flow rate at 1 ml/min. The mass spectrometer was operated in electron ionization (EI) mode with an ionization energy of 70 eV, and the mass spectra were acquired over a range of m/z 45–550. NIST 2017 Libraries was used in compound identification.

Attenuated total reflectance fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR)

Non-invasive surface analysis was performed using an Agilent 4300 handheld FTIR spectrometer (Agilent Technologies). Spectra were acquired in the 4000–650 cm–1 range with 4 cm−1 resolution and 64 scans. Data were normalized before visualization.

X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis

Qualitative and semi-quantitative X-ray fluorescence (XRF) measurements were performed on samples using a Bruker TRACER 5 g handheld spectrometer under a helium (He) atmosphere. The instrument utilized a detector equipped with a 1 μm graphene window, enabling the detection of elements ranging from Na (Z = 11) to U (Z = 92). The precious metal mode from the instrument was selected to test. The working parameters were 40 kv for excitation voltage; 11.5 μA for current; test time was 30 s. Tests were carried out for comparison between the ink area and the blank part of each sample, respectively.

Results

Radiocarbon dating

The radiocarbon dating results of the manuscript fragments are presented in Table 1. Sample XZDL-1 yielded a radiocarbon age of 787 ± 18 BP, which calibrates to 1224–1273 cal AD (95.4% confidence interval). Historical records indicate that Taklung Monastery was established in the late 12th century. The dating results place the fragments within the 13th century, align well with the monastery’s construction and early usage period.

Information on the text of the fragments

The contents recorded on the two fragments primarily consist of Sanskrit dhāraṇīs transcribed in Tibetan cursive script, along with one Tibetan-written prayer. Dhāraṇīs generally refer to longer mantras with diverse content forms. Collectively, these two manuscript fragments express devotion to various Buddhist figures and convey aspirations for a blessed life.

The specific details revealed by hyperspectral imaging are as follows (Fig. 3):

XZDL-1

-

1.

… namo ma(ni)ratna …

-

2.

gu(h)y(a)ratna ma … uṃ …. namo ratna .. ratna ..

-

3.

thra vaṃ dmaṃ chu sa myed bu a ra sa ya sras dang d… dang ..

-

4.

ri .. ru ma vya sa smyod (tsh)i(g) gsung bar sa grus cing rang sems

-

5.

’khrul pa dag pa dang | ’gro ba’i yon tan ’dus par shog | oṃ

-

6.

hriḥ ha ha hūṃ hūṃ phaṭ | oṃ oṃ oṃ sa(r)ba(buddha)ḍākiniye

-

7.

vajravarṇṇaniye vajrabhairaconiye(vajravairocaniye?)

-

8.

.. bharimi …

-

9.

…. | oṃ …. bhai ya | steṃ ṇa …. rna ra .. man

-

10.

… | oṃ …

XZDL-2

-

1.

…

-

2.

… .. ma ma ba bud re | .. vaṃ hūṃ hūṃ ….

-

3.

svā (hā) || oṃ ḍākani ḍākani | recini recini | re

-

4.

ṭani reṭani | trasani trasani | srarirana srarira |

-

5.

sa …. | (ma)d sa ba ra ṇa saraṃ saraṇime guru svāhā ||

-

6.

oṃ sarmaduṣṇīṣavi(ja)ya(par)iśuddhe | hūṃ hūṃ svāhā

-

7.

oṃ sa(rma)duṣṇīṣa(vija)ye hūṃ phaṭ || oṃ maṇi

-

8.

padme hūṃ | oṃ bu svāhā ||

Note: ‘…’: multiple unrecognisable syllables; ‘..’: one indecipherable syllable; ‘.’: part of an indecipherable syllable; ‘()’: reconstructed syllable; ‘|’: separator.

The manuscript XZDL-1 contains two distinct genres: mantra and prayer. Notably, the mantra section demonstrates particular veneration for three key Buddhist deities: Sarvabuddhaḍākinī, Vajravarṇanī, and Vajravairocanī. In contrast, XZDL-2 consists exclusively of mantra texts, featuring invocations to Ḍākinī and Uṣṇīṣavijaya, both significant figures in Buddhist tradition. This fragment concludes with the auspicious six-syllable mantra, a particularly renowned and symbolically important mantra within Buddhist practice. Both fragments consistently reference objects of worship that exhibit strong connections to esoteric Buddhist traditions historically prevalent in the TAR.

Microscopic examination

The manuscript fragments XZDL-1 (89.42 × 43.30 × 0.18 mm) and XZDL-2 (94.90 × 48.24 × 0.13 mm) exhibit an irregularly shaped, brownish-yellow appearance. The upper and lower edges show clean, straight cuts indicating deliberate trimming, while the irregular lateral edges with abruptly terminated text suggest the complete manuscript was torn vertically (Fig. 4).

Multiple distinct east-west oriented creases indicate repeated folding prior to deposition. Combined with the observed surface creases and irregular central fracture patterns, this suggests intentional fragmentation to facilitate insertion into the narrow cavity of the statue. The crude tearing patterns imply rough handling during this process.

The rough surface texture displays 0.5–1.0 cm long black striations resembling the lenticels characteristic of birch bark. The reddish-brown coloration corresponds well with the active deeper cork layers (phelloderm) of birch. However, these morphological features alone are insufficient for definitive species identification, necessitating complementary analytical approaches.

ATR-FTIR analysis

Comparative analysis was conducted using modern birch bark (Betula utilis) samples as reference. The infrared spectra of the manuscript fragments showed remarkable similarity to the birch bark reference samples. The spectral features were characterized as follows (Fig. 5). The presence of characteristic peaks for lignin, hemicellulose, and carbohydrate components confirms the preservation of original organic components in the historical material. The close spectral match between the manuscript fragments and modern birch bark samples, particularly in the fingerprint region (1800–800 cm−1), provides strong evidence for the bark origin of the writing substrate. Identification of vibration type of peaks and their origins was displayed in Table 2. Furthermore, the ancient samples exhibit high morphological and compositional similarity to modern counterparts, suggesting their well-preserved condition. These samples were found deeply compacted within tsha-tsha, which may have provided a unique environment conducive to their preservation.

ATR-FTIR spectroscopy offers a viable method for identifying ink components, including binders, pigments, and adhesives14,15. However, in this study, the spectral signals corresponding to these compounds were notably weak. Comparative analysis of blank and inked areas revealed a high degree of spectral similarity, suggesting minimal detectable differences. This limitation likely arises from matrix effects caused by the substrate, compounded by the extreme thinness of the ink layer.

THM-Py-GC/MS analysis

THM-Py-GC/MS analysis identified multiple triterpenoid compounds eluting between 30.00 and 37.00 min (Fig. 6; Table 3). Comparative analysis with reference literature16,17 and the NIST 2017 mass spectral library confirmed the presence of lupane-type, oleanane/ursane-type, and other pentacyclic triterpenoids.

The mass spectrum exhibited a characteristic high-abundance fragment ion at m/z 189 (Fig. 7a), diagnostic for lupane-type triterpenoids. This signature fragment originates from C-ring cleavage at the C9-C11 and C8-C14 bonds, followed by elimination of a water molecule from the C3-hydroxyl group. Three prominent compounds (29, 24, and 27) showed distinctive fragmentation patterns at m/z 262, 203, and 189, characteristic of methyl oleanolate derivatives (Fig. 8). Specifically: m/z 262 results from retro-Diels-Alder (RDA) cleavage of the D/E rings. m/z 203 derives from A/B ring demethoxylation. m/z 189 arises through D/E ring demethylation.

Furthermore, compounds 33 and 36 demonstrated concurrent fragment ions at m/z 189 and 203, confirming their pentacyclic triterpenoid nature. The analysis also revealed substantial quantities of co-eluting compounds, including fatty acid esters, aromatic methyl ethers, and aliphatic hydrocarbons (Table 3).

It is widely recognized that birch bark is primarily rich in a series of lupane-type derivatives, betulin derivatives, and minor amounts of oleanane- and ursane-type triterpenoids18,19,20,21,22. These terpenoids exhibit high chemical stability and can be detected not only in fresh birch bark but also in archaeological samples subjected to prolonged burial23,24, making them crucial biomarkers for determining the plant origin of such materials. Py-GC/MS analysis of ancient birch bark tar readily yields a characteristic series of lupane-type triterpenoids16,17, which share a compositional profile similar to that of birch bark itself24.

In this study, a significant abundance of lupane-type triterpenoids, along with trace amounts of oleanane-type triterpenoids, was detected, strongly supporting a close association with the genus Betula. However, in addition to terpenoids, birch bark also contains suberin, procyanidins, lignin, and other macromolecular constituents. Further analysis of these additional components could provide more definitive evidence for identifying the precise material source of the manuscript fragments.

The TMAH derivatization coupled with Py-GC/MS proves highly effective in detecting components containing polar functional groups such as esters. This method facilitates the cleavage and methylation of macromolecules at polar functional groups while minimizing the fragmentation of alkyl C–C bonds, thereby preserving alkyl chain length information to the greatest extent. The TMAH derivatization typically converts hydroxyl groups into methoxy groups, yielding derivatives such as ethers and esters.

The analytical results revealed that the birch bark excavated from Taklung Monastery contains a substantial abundance of methyl esters and methyl ether derivatives, including saturated and unsaturated fatty acids, as well as methyl esters of ω-hydroxy fatty acids. Additionally, a series of long-chain dicarboxylic acids were identified. Previous studies have demonstrated that long-chain dimethyl esters, formed through derivatization of dicarboxylic acids, typically produce characteristic fragment ions at m/z 98 during mass spectrometric cleavage (Fig. 7b)25,26. The ion chromatograms obtained in this study confirmed the presence of multiple dimethyl esters of dicarboxylic acids (peaks 4, 8, 15, 18, 22, and 25), with carbon chain lengths predominantly ranging from C8 to C22 and showing an even-numbered carbon preference. Among these, compounds with C16, C18, and C22 carbon chains exhibited the highest peak intensities. In addition to carboxylic acid derivatives, the results also indicated the presence of unsaturated aliphatic alcohols (peak 17) and linear alkenes (peak 7).

Multiple studies have demonstrated that birch bark tar contains not only a series of terpenoids but also homologous linear saturated/unsaturated mono- and dicarboxylic acids, n-alkenes, n-alkanes, and ω-hydroxy fatty acids16,17,27. These compounds are likely derived from suberinic biopolymers and may serve as diagnostic criteria for birch bark identification.

In this study, the detected carboxylic acid derivatives exhibited remarkable structural similarity to the monomeric constituents of suberin—a biopolyester primarily composed of hydroxy, epoxy, and dicarboxylic acids. Upon derivatization and depolymerization, suberin typically yields C16, C18, C22, and C24 ω-hydroxy fatty acids and dicarboxylic acids as dominant components28,29. The abundant presence of suberin-derived compounds in our pyrolysis results aligns with previous findings on birch bark tar, further validating the reliability of our analytical approach.

Notably, several aromatic dimethyl ether derivatives (peaks 3, 6, 9, 10, 11) were identified. These compounds are characteristic pyrolysis products of guaiacyl (G)-type lignin, originating from residual lignin in the bark. The detection of G-type lignin is consistent with the ATR-FTIR results. Unlike the xylem of most angiosperms where syringyl (S)-type lignin predominates, birch bark has been reported to contain significantly higher proportions of G-type lignin28, likely reflecting tissue-specific physiological differences within the same plant. The predominance of G-type lignin in our samples provides additional evidence supporting the compositional consistency between the manuscript fragments and birch bark.

Composition analysis of manuscript inscriptions

Combined with spectral feature analysis, two samples primarily contain five main elements (>0.1%): Au, Fe, Cu, Rh, and Pd. Among these, Rh and Pd are elements generated by the instrument itself during testing and can thus be excluded as contributors to the sample composition.

In these two samples, the content of Au is significantly elevated in the ink areas, with spectral results showing that the energies of Au Lα and Au Mα are markedly higher than those in blank regions. In contrast, the peak energies of Fe Kα and Cu Kα exhibit no significant variation, indicating similar concentrations in both the ink and blank areas (Fig. 9; Table 4). This suggests that the written portions contain a higher content of Au. Naturally grown birch bark is primarily composed of organic matter and typically contains minor amounts of metallic elements. The presence of these Fe and Cu elements may be associated with the burial environment of the samples.

Discussion

Birch bark, as a writing material with a long history, has been documented across various cultures worldwide. During the 19th century, several birch bark manuscripts were discovered in Central Asia, including the Bower Manuscript, the Bajaur Collection, the Gāndhārī Dharmapada (Kharoṣṭhī script), and the Gilgit Manuscripts. Among these, the Bower Manuscript was first unearthed in Kucha, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China, and later acquired by Lieutenant Hamilton Bower of the British Indian Army in the late 19th century. Currently housed in the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford, this manuscript comprises 56 birch bark folios inscribed with ancient Sanskrit in Brāhmī script. Dating to the 4th–6th centuries AD, it preserves invaluable content on early Indian medicine, divination, and other subjects, holding significant historical and scholarly importance.

Since the 1990s, numerous fragments and scrolls of Kharoṣṭhī-script birch bark manuscripts (1st century BC–3rd century AD) have been recovered, predominantly containing Buddhist texts30. Beyond religious purposes, birch bark served diverse functions—recording letters, contracts, legal agreements, debt records, and legal codes31, highlighting its versatility as a writing medium. Its utilization persists into modern times, with documented examples from India, Northeastern China, Afghanistan, Pakistan, the North American Great Lakes region, Novgorod (Russia), and Mongolia30,32,33, typically surviving as fragments or bound codices.

In India, birch bark itself was regarded as sacred. In addition to its role as a writing substrate, it was fashioned into amulets enshrined in stupas or worn as personal talismans34. Excavations in Kashmir, Afghanistan, and Pakistan have yielded abundant birch bark fragments, often stored in clay jars or stupas35. This deliberate deposition reflects a ritual practice aimed at preserving sacred Buddhist scriptures. Some fragments were even placed within the hands of Buddha statues. Paleographic analysis of Kharoṣṭhī fragments reveals that their contents predominantly feature Buddhist texts in varied literary forms, distinguishing their ritual function from intact sutra scrolls.

The birch bark manuscript from Taklung Monastery was discovered inside a small tsha-tsha—a clay votive stupa prevalent in Tibetan Buddhism, typically used as filler material within larger stupas36. The bark had been intentionally folded and stored within the figurine, inscribed with Buddhist hymns and mantras. This depositional context parallels ancient practices in Gandhara, underscoring a shared religious intentionality. The Taklung manuscript thus exemplifies not only textual transmission but also the symbolic significance of its materiality, reflecting the multifaceted cultural perceptions and utilitarian diversity of writing materials in ancient TAR.

The Qinghai-Tibet Plateau is rich in birch (Betula spp.) resources. As a genus of deciduous trees widely distributed across the boreal and temperate zones of the Northern Hemisphere, Betula comprises approximately 100 species, many of which thrive in high-altitude and high-latitude regions. Within the alpine vegetation zone of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, 12 birch species have been documented, including Betula alnoides, Betula cylindrostachya, Betula utilis, and Betula platyphylla37,38. Notably, Betula utilis (Himalayan birch) is widely distributed across the Himalayan range at elevations of 2700–4500 m39. Given the region’s geographical constraints and limited access to external resources, locally abundant birch species likely served as the primary raw material for producing manuscript fragments.

The Himalayan orogeny endowed Qinghai-Tibet Plateau with abundant mineral resources, including typical gold deposits and gold-bearing ore belts40. Historical records indicate that gold mining and utilization flourished during the Tubo Dynasty. The Old Book of Tang notes that Tubo abounds in gold, silver, copper, and tin and all of comparable quality. A document unearthed in Dunhuang recounts that in the summer of the Dog Year (746 AD), the King hosted a banquet at the Gserkhung (gold mine). These accounts confirm gold mining activities in Tubo prior to the 7th century.

Tibetan metalworking technology was equally advanced. The Cefu Yuangui (冊府元龜), a Song Dynasty encyclopedic historical text, documents that Tibetans had mastered quenching techniques for metal processing. A gilded forged copper bowl excavated from a Tibetan tomb in Tzethang, Shannan City41, further attests to sophisticated metallurgical skills during the Tubo Dynasty33. The Old Book of Tang also records that in 736 AD, Tubo King sent envoys to the Tang court bearing “hundreds of gold and silver artifacts of extraordinary craftsmanship.” These evidences collectively demonstrate advanced capabilities in mining, metallurgy, and metal artistry in Tubo Dynasty.

Within this well-established mining and processing system, the gold ink employed in the Taklung manuscript was likely produced locally. While pure gold represented the most prestigious material for gold-like inks, its prohibitive cost led to the development of alternative preparation methods as documented in historical Tibetan texts. One such method involved blending ‘equal parts gold or glue, thickened sesame oil, and copper’ to create a more affordable substitute42. In this study, the Taklung manuscript’s gold-like ink consists predominantly of gold. Comparative analysis between ink and blank area showed no significant variation in Cu. The notably high gold concentration further attests to the manuscript’s exceptional cultural and material value.

Gold-like ink is commonly observed in Buddhist scriptures, typically applied to dark-colored paper (e.g., indigo or black), like dark-blue paper, to enhance visual contrast through the interplay of dark backgrounds and luminous script. Dark-blue paper was traditional Tibetan writing material and produced through an elaborate manufacturing process. When combined with gold ink, it was considered as deluxe edition and was precious material symbolizing great sanctity and highly cherished43. While numerous Tibetan literary sources document the use of gold ink in manuscript production, detailed descriptions of the accompanying writing materials remain conspicuously absent from these records. In particular, the question of whether all such manuscripts employed dark-blue paper as their substrate remains unresolved in current scholarship42,44. In this study, we provide the evidence for the use of gold ink on birch bark in Tibetan manuscript production. This discovery offers new insights into the diversity of Tibetan manuscript production techniques.

Through a comprehensive analytical approach involving radiocarbon dating, morphological examination, ATR-FTIR, and THM-Py-GC/MS, this study has successfully identified the manuscript fragments excavated from Taklung Monastery as birch bark, dating to approximately the 13th century. Furthermore, p-XRF analysis revealed that the ink used in the manuscripts was predominantly composed of gold (Au). The manuscript’s content and archaeological context indicate that these birch bark manuscripts served religious purposes. The availability of local resources and a well-developed metal production system provided the foundation for local production. Notably, this study reports the utilization of gold ink on birch bark, which offers significant insights into the manuscript craft of ancient Tibetan during the 13th century.

Data availability

The datasets used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Hunter, D. Papermaking: The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft (Courier Dover, 1978).

Agrawal, O. P. Conservation of Manuscripts and Paintings of South-East Asia (Butterworth, 1984).

Srivastava, S. The legacy of treasure: manuscript. Open Access J. Arch. Anthropol. 2, 1–17 (2020).

Xiong, W. The ancient Tibet-Nepal pathway and its historical role. China Tibetol. 1, 38–48 (2020). [in Chinese].

Tsewang, R. A study on Tibetan paper. Tibet. Stud. 1, 83–88 (2002). [in Chinese].

Helman-Ważny, A. Overview of Tibetan paper and papermaking: history, raw materials, techniques and fibre analysis. in Tibetan Manuscript and Xylograph Traditions. The Written Word And Its Media Within The Tibetan Culture Sphere (ed Almogi, O.) (Universität Hamburg, 2016).

Helman-Ważny, A. & Ramble, C. Tibetan documents in the archives of the tantric lamas of Tshognam in Mustang, Nepal: an interdisciplinary case study. Rev. Étud. Tibétaines. 39, 266–341 (2017).

Han, B. et al. Paper fragments from the Tibetan Samye Monastery: clues for an unusual sizing recipe implying wheat starch and milk in early Tibetan papermaking. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 36, 102793 (2021).

Helman-Ważny, A. The choice of materials in early Tibetan printed. in Tibetan Printing: Comparison, Continuities and Change (eds Diemberger, H., Ehrhard, F.-K., Kornicki, P.) (Brill, 2016).

Luo, Y., Cigić, I. K., Wei, Q., Marinšek, M. & Strlič, M. Material properties and durability of 19th–20th century Tibetan manuscripts. Cellulose 30, 11783–11795 (2023).

Shi, J. et al. Modern technical analysis of a group of ancient Xizang papers. J. Fudan Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 63, 586–597 (2024). [in Chinese with English abstract].

van Schaik, S., Helman-Ważny, A. & Nöller, R. Writing, painting and sketching at Dunhuang: assessing the materiality and function of early Tibetan manuscripts and ritual items. J. Archaeol. Sci. 53, 110–132 (2015).

Helman-Ważny, A. & van Schaik, S. Witnesses for Tibetan craftsmanship: bringing together paper analysis, palaeography and codicology in the examination of the earliest Tibetan manuscripts. Archaeometry 55, 707–741 (2013).

Haberová, K., Jančovičová, V., Vesela, D., Machatova, Z. & Oravec, M. Impact of organic binders on the carminic-colorants stability studied by: ATR-FTIR, VIS and colorimetry. Dyes Pigments 186, 108971 (2021).

Pięta, E., Olszewska-Świetlik, J., Paluszkiewicz, C., Zając, A. & Kwiatek, W. M. Application of ATR-FTIR mapping to identification and distribution of pigments, binders and degradation products in a 17th century painting. Vib. Spectrosc. 103, 102928 (2019).

Ribechini, E., Bacchiocchi, M., Deviese, T. & Colombini, M. P. Analytical pyrolysis with in situ thermally assisted derivatisation, Py(HMDS)-GC/MS, for the chemical characterization of archaeological birch bark tar. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 91, 219–223 (2011).

Lyu, N. et al. Microdestructive analysis with Py-GC/MS for the identification of birch tar: a case study from the Huayang site in late Neolithic China. EPJ 138, 580 (2023).

Hordyjewska, A., Ostapiuk, A., Horecka, A. & Kurzepa, J. Betulin and betulinic acid: triterpenoids derivatives with a powerful biological potential. Phytochem. Rev. 18, 929–951 (2019).

Yin, J. et al. Expression characteristics and function of CAS and a new beta-amyrin synthase in triterpenoid synthesis in birch (Betula platyphylla Suk.). Plant Sci. 294, 110433 (2020).

Wang, S., Zhao, H., Jiang, J., Liu, G. & Yang, C. Analysis of three types of triterpenoids in tetraploid white birches (Betula platyphylla Suk.) and selection of plus trees. J. Res. 26, 623–633 (2015).

Popov, S. A., Sheremet, O. P., Kornaukhova, L. M., Grazhdannikov, A. E. & Shults, E. E. An approach to effective green extraction of triterpenoids from outer birch bark using ethyl acetate with extractant recycle. Ind. Crops Prod. 102, 122–132 (2017).

Savichev, A. A. et al. Typomorphic features of placer gold from the Bystrinsky ore field with Fe-Cu-Au skarn and Mo-Cu-Au porphyry mineralization (Eastern Transbaikalia, Russia). Ore Geol. Rev. 129, 103948 (2021).

Rao, H., Yang, Y., Hu, X., Yu, J. & Jiang, H. Identification of an ancient birch bark quiver from a Tang dynasty (A.D. 618–907) Tomb in Xinjiang, Northwest China. Econ. Bot. 71, 32–44 (2017).

Aveling, E. & Heron, C. Identification of birch bark tar at the Mesolithic site of Star Carr. Anc. Biomol.2, 69–80 (1998).

Li, M. et al. Isolation and identification of six difunctional ethyl esters from bio-oil and their special mass spectral fragmentation pathways. Energ. Fuel 32, 10649–10655 (2018).

Ren, M. et al. Birch bark tar ornaments: identification of 2000-year-old beads and bracelets in Southwest China. Archaeol. Anthr. Sci. 15, 186 (2023).

Niekus, M. J. L. T. et al. Middle Paleolithic complex technology and a Neandertal tar-backed tool from the Dutch North Sea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA116, 22081–22087 (2019).

Tegelaar, E. W., Hollman, G., Van Der Vegt, P., De Leeuw, J. W. & Holloway, P. J. Chemical characterization of the periderm tissue of some angiosperm species: recognition of an insoluble, non-hydrolyzable, aliphatic biomacromolecule (suberan). Org. Geochem. 23, 239–251 (1995).

del Río, J. C. & Hatcher, P. G. Analysis of aliphatic biopolymers using thermochemolysis with tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH) and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Org. Geochem. 29, 1441–1451 (1998).

Lyu, X. An overview of conservation and restoration for birch bark manuscripts. in Proceedings of the 9th Academic Annual Conference of China Association for Preservation Technology of Cultural Relics (ed CAPTCR) (Science Press, Beijing, 2018).

Mendoza, I. Old East Slavic Birch-Bark Literacy—a history of linguistic emancipation?. Russ. Linguist. 47, 343–365 (2023).

Harrison, P., Lenz, T. & Salomon, R. Fragments of a Gāndhārī manuscript of the pratyutpannabuddhasaṃmukhāvasthitasamādhisūtra (studies in Gāndhārī manuscripts 1). J. Int. Assoc. Buddh. Stud. 41, 117–143 (2018).

Kano, K. & Szántó, P.-D. New pages from the Tibet museum birch-bark manuscript (1): fragments related to Jñānapāda. J. Kawasaki Daishi Inst. Buddh. Stud. 5, 27–51 (2020).

Agrawal, O. Conservation of birch-bark manuscripts–some Innovations. Int. Preserv. N. 50, 36–38 (2010).

Strauch, I. Looking into water-pots and over a Buddhist scribe’s shoulder – on the deposition and the use of manuscripts in early Buddhism. Asiat. Stud. - Étud. Asiat. 68, 797–830 (2014).

Sonam, T. The origins, structural features, and classification of Tibetan stupas. Tibet. Stud. 2, 82–88 (2003). [in Chinese].

Jiang, J. The study of the geographical distribution of the Betula in China. For. Res. 1, 55–62 (1990). [in Chinese with English abstract].

Khuroo, A. A. et al. Patterns of Plant Species Richness Across the Himalayan Treeline Ecotone (Springer Nature Singapore, 2023).

Polunin, O., Stainton, A. Flowers of the Himalaya (Oxford University Press, 1984).

Zhai, W. et al. Geology, geochemistry, and genesis of orogenic gold–antimony mineralization in the Himalayan Orogen, South Tibet, China. Ore Geol. Rev. 58, 68–90 (2014).

Gedun A gilded copper bowl from the Tibetan Empire Period in the collection of the Tibet cultural relics administration committee. Cult. Relics 11, 81 (1985). [in Chinese].

Zhu, L. A preliminary survey on mthing shog manuscripts. J. Tibetol. 2, 134-150+307-308 (2019). [in Chinese].

Wangchuk, D. Sacred words, precious materials: on Tibetan deluxe editions of Buddhist scriptures and treatises. In Tibetan Manuscript and Xylograph Traditions. The Written Word and Its Media Within the Tibetan Culture Sphere (ed Almogi, O.) (Universität Hamburg, Hamburg, 2016).

Pasang, W. Methodological re-examination in the study of old Tibetan manuscripts. China Tibetol. 3, 61-81+257 (2009). [in Chinese].

Zhang, T., Guo, M., Cheng, L. & Li, X. Investigations on the structure and properties of palm leaf sheath fiber. Cellulose 22, 1039–1051 (2015).

Chung, C., Lee, M. & Choe, E. K. Characterization of cotton fabric scouring by FT-IR ATR spectroscopy. Carbohydr. Polym. 58, 417–420 (2004).

Shi, Z. et al. Structural characterization of lignin from D. sinicus by FTIR and NMR techniques. Green. Chem. Lett. Rev. 12, 235–243 (2019).

Ma, Z., Sun, Q., Ye, J., Yao, Q. & Zhao, C. Study on the thermal degradation behaviors and kinetics of alkali lignin for production of phenolic-rich bio-oil using TGA–FTIR and Py–GC/MS. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 117, 116–124 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFF0903901).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Q.C., H.J.; Methodology: Q.C., S.W., Y.Y.; Formal analysis, Writing-original draft: Q.C.; Writing -review and editing: H.J., T.T.; Resources: T.T.; Text information analysis: E.S.; Project administration, Supervision: H.J. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Q., Tashi, T., Wang, S. et al. Characterization of a 13th-century Tibetan birch bark manuscripts: investigating utilization and craftmanship. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 480 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01999-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01999-y