Abstract

Artists often assess that Chinese brushes’ performances rely on macroscopic writing experience, while they seldom consider the underlying reasons for differences from experimental science. However, the correlation between materials and writing performance can be utilized to advance brush materials and develop traditional Chinese calligraphy. In this study, we examined the provenance of the diverse range of natural or man-made fibers and hairs. The hairs of herbivores, such as sheep and rabbits, exhibit a superior layered structure and a reduced level of grease, which provides an explanation for the microscopic level at which rabbit hair has become a popular brush material. The subsequent incorporation of polydopamine markedly enhanced the ink absorption capacity of the rabbit hair Chinese brush, exhibiting a remarkable degree of responsiveness and ink adsorption stability during creation. Our results indicate a significant correlation between brush writing performance and material selection, which provides guidance for the modern creation of calligraphy art.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the inaugural item among the Four Treasures of the Scholar’s House, traditional Chinese brushes served as the primary instruments of artistic expression for ancient Chinese scholars1,2,3. Traditional Chinese narratives such as the tale of Meng Tian’s brush-making and the story of the extraordinary brushes that produce flowers have achieved a status as exemplary accounts within the annals of brush-related folklore. As the saying goes, “To do a good job, you must first sharpen your brush.” Ancient Chinese calligraphy and painting developed alongside Chinese brushes. These brushes play a key role in Chinese cultural history4,5. In comparison to the extensive historical development of the Chinese brush, there is a paucity of literature focused on the subject of Chinese brushes. In essence, the study of Chinese brush-making only gained traction after the advent of the Song Dynasty. It was not until the Qing Dynasty that Liang Tongshu produced the inaugural “History of the Chinese Brush”6, which was devoted to the examination of Chinese brushes and represented a seminal moment in the history of Chinese brush studies7.

The relationship between the brush system and the style and concept of calligraphy has been a topic of considerable debate and discussion throughout the Tang and Song dynasties. Notable contemporary scholars such as Chen Zhiping, Zhu Youzhou, and Wang Xuelei have made significant contributions to this field of study. Chen explores the original meaning of the phrase “Heart is the brush” as articulated by Liu Gongquan (Tang Dynasty). Chen’s analysis suggests that the term “brush” is used to signify the act of writing, the instrument used for writing, and the concept of writing itself. The article discusses Liu Gongquan’s statement that “if the heart is right, the brush is right” and posits that by employing the “brush” to communicate with “the heart of heaven and earth” and “the human heart,” he effectively documented the significant transformation in the craft of making brush and the concept of calligraphy during the Late Tang Dynasty. However, in contrast to the approaches, this paper adopts a microcosmic perspective, focusing on the specific material of the brush. The objective is to elucidate the interconnection between the manipulation of the brush and the stylistic nuances of the resulting calligraphic work. In other words, how did the ancient calligraphers, exemplified by figures such as Su Shi and Huang Tingjian, who grappled with the distinctive and nuanced characteristics of the material during the writing process, reflect upon these observations?

Ancient calligraphy and historical documents provide insight into the evolution of the brush system and the concept of calligraphy. They illustrate the esthetic concepts of calligraphy during the Tang and Song dynasties, as well as the interaction between style formation and the writing experience. For example, the Northern Song Dynasty Su Yijian’s “the Four Treasures of the Scholar’s House” contains information about the Chen family in Xuanzhou, who were skilled in the production of brushes. The Chen family has a long history of excellence in the craft of brush-making, tracing its lineage back to Wang Xizhi and Chen’s ancestor, who is known as the “brush post.” The Chen family’s later descendants have particularly distinguished themselves in this tradition. In the Tang Dynasty, the celebrated calligrapher Liu Gongquan requested a brush from the Chen family in Xuancheng. Chen’s initial provision of two distinct writing implements to Liu Gongquan and Wang Xizhi afforded them the opportunity to utilize them in a comparative manner. After initially attempting to ascertain their proficiency with the given brush, Liu Gongquan discovered that the Xuancheng Chen-provided brush was more conducive to their demands. This shows Liu Gongquan’s brushes are unfit for Wang Xizhi. Their writing techniques and esthetics differed greatly. Xie Zhaoxiang’s “Five Miscellaneous Group” provides a comprehensive account of the divergence between Liu Gongquan and Wang Xizhi’s calligraphic styles. He proposes that the defining feature of Liu’s work is its emphasis on “just, soft points.” At that time, Wang Xizhi’s customary brush was the mouse-beard brush, which exhibited a pronounced “bitter strength” during the writing process. This quality rendered it unsuitable for use by calligraphers who lacked the requisite skill to effectively handle the brush. Moreover, the Tang Dynasty witnessed the advent of the “just brush” as championed by Ouyang Xun and Yu Shinan. This resulted in a more pronounced divergence in the performance of the writing tool.

However, it is a genuine reflection of the essential role of the material used for the brush and hair in the writing process, which can be described as a movement from the inside to the outside. In the small invitation with Huang Ancient, Zhu Xi stated that Yu’s brush was not moth-eaten, but that its performance was otherwise deficient. He identified several shortcomings, including a “twisting heart” that was not aligned with the main front, a Fu hair that was too thin, and a lack of sufficient suppression of the press. In Zhu Xi’s description, the term “the shortness of this also” is used to denote the same brush head elasticity that is determined by the brush hair. To more fully illustrate the question of the brush hair (material) of its own properties, we cite the Song Su Yijian record of the Tang Duan Chengshi, which states, “Send Yu Zhigu 10 tubes of San Zhuo brush and 10 tubes of soft brush.” The San Zhuo brush is a type of ancient brush that does not utilize a hair column. This paragraph of the text can also be used to confirm the claim. This historical material provides a detailed account of the characteristics of brush hair since ancient times. It begins by discussing the history of painting and calligraphy tools and materials. At that time, the hair of the brush was harder than rabbit hair and softer than sheep hair. In essence, the necessity of the era required a combination of these qualities. In conclusion, there was a practical necessity to enhance the brush in accordance with the demands of the era. In modern science, many methods are used for surface modification, such as plasma sputtering, chemical modification, and water-based modification. However, for the modification of brushes, it is necessary to ensure that the properties of the brushes themselves are not destroyed. Therefore, it is necessary to use a mild method for modification. Dopamine has good oxidative polymerization properties and has been used in fields such as biomaterial surface modification. Using it in brush modification may be a very novel and worthy field to explore.

In the process of artistic creation, individuals frequently evaluate the performance of various Chinese brushes based on their macroscopic experience with writing or drawing. However, they seldom consider the underlying reasons for these differences from the perspective of modern experimental science. Considering the aforementioned background, it is imperative to elucidate the correlation between brush materials and writing performance. This understanding can then be utilized to develop novel brush materials that will facilitate the dissemination and advancement of traditional Chinese calligraphy and Chinese landscape painting. Accordingly, this study examines the microstructure and performance differences of various Chinese brushes from the vantage points of experimental science and material science, with the objective of establishing a correlation between Chinese brush materials and artistic creations. Concurrently, we also endeavor to enhance the writing experience of Chinese brushes through surface modification, thereby offering novel insights that can inform the advancement of future Chinese brush designs.

Methods

Materials

Brushes and hairs are sourced from the town of Wengang, Jiangxi Province, China. The animal hairs are sourced from captive-bred animals. Nylon was obtained from Zhejiang Jiahua Special Nylon Co., Ltd. Tris (hydroxymethyl) aminomethane (Tris) and dopamine hydrochloride were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Ethanol and other reagents were of analytical grade and purchased from Guangzhou Chemical Reagent Plant.

Characterization

The morphologies of the fibers were observed through a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM, ULTRA 55, Carl Zeiss, Germany) with 15 kV acceleration voltage. In detail, the samples were first dried and dehydrated and then glued to the aluminum table with conductive tape for observation. Fourier transform-infrared (FTIR) spectra were acquired using a Bruker EQUINOX55 FTIR spectrophotometer (Germany) in the range 400–4000 cm−1 at a 10 kHz of scanning frequency. The liquid crystal texture of fibers was observed under a polarizing optical microscope (POM, BX53 M, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) fitted with a digital camera (DP200), and the POM polarizer orientation is 45°.

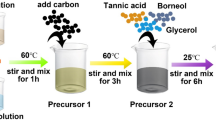

Modification of polydopamine (PDA) layer on a Chinese brush based on oxidative self-polymerization reaction

The initial step involved the preparation of a Tris-HCl buffer solution with a pH value of 8.5. Subsequently, a solution with a 2 g/L concentration of the reaction mixture was prepared by the addition of dopamine hydrochloride powder to the aforementioned buffer solution8,9,10. Once the powder had been fully dissolved, the rabbit hair was completely impregnated into the reaction solution. The reaction was carried out in an air atmosphere protected from light for 12 h at room temperature. Thereafter, the solution was removed and rinsed several times, and vacuum drying was employed to obtain the PDA-modified rabbit hair Chinese brush.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Origin 2017 software. The quantitative results were exhibited as mean ± standard deviation, and one-way ANOVA analysis of variance was employed to make the statistical analysis.

Results

Micromorphology and topography of different Chinese brushes

Chinese brushes are crafted from an array of materials with varying characteristics. The classification of ancient Chinese brush material is based on the characteristics of the hairs used in its composition. These include hard hair, soft hair, and mixed hair. Hard hair is more flexible and includes materials such as rabbit hair, weasel hair, rat whisker hair, and mountain horsehair. Soft hair is less flexible and softer, comprising materials such as sheep hair, chicken hair, tire hair, and so forth11. Mixed hair is a combination of hard and soft hair, and is typically made with a different proportion of animal hairs, with the hard hair forming the nucleus and the soft hair wrapped around it. For example, mixed Chinese brushes have been developed with a composition comprising a harder outer layer of weasel hair and a softer inner layer of wool12. Nevertheless, the utilization of these animal hairs is currently constrained by wildlife protection regulations. Consequently, a multitude of natural and synthetic polymers are employed in the fabrication of Chinese brushes recently, including nylon and hemp fibers13,14,15,16, which are amenable to large-scale production and exhibit consistent properties. It is unfortunate that these fibers are not as effective as animal hair in retaining ink or creating works of art. Most art scholars focus on artistic content. They rarely study brush materials. This has resulted in a paucity of systematic research into the materials used to create Chinese brushes. However, with the advent of modern science and technology and analytical characterization techniques, artists and material scientists have discovered that the selection of materials for Chinese brushes is of paramount importance to artistic creation, exerting a direct influence on the form and content of artistic production. In order to more accurately reflect the artist’s intentions, it is imperative to establish a clear correlation between Chinese brush materials and artistic creation.

In ancient China, brushes were crafted from an array of materials, including plant fibers and animal hair, which were utilized in their fabrication. A variety of materials, including abutilon fiber, sheep, rabbit, pig, and weasel hair, were utilized in the production of brushes1,6. Some of these materials remain in use in the modern era. Additionally, some synthetic fibers, such as nylon, are employed in the fabrication of brushes. Initially, the micromorphology and topography of Chinese brushes crafted from disparate materials were examined through FESEM, as illustrated in Fig. 1A, B. A single fiber was selected for all fibers for observation. In a large field of view (1000×), abutilon fibers have very dispersed inter-fiber interaction, while other fibers do not have any division. This phenomenon may be attributed to the inherent rigidity of abutilon fibers, which are primarily composed of cellulose in the cell wall. During the process of water loss, these fibers exhibit a certain degree of rigidity, resulting in a high susceptibility to splitting. Besides, the advanced preparation process ensures that the nylon fiber surface is exceptionally smooth14. Upon closer examination, the nylon surface showed evidence of processing, manifesting as a disorderly surface structure. Unlike plant fibers, animal hair is a gradual process of growing in layers. As shown in Fig. 1B, all animal hairs are tightly linked and do not split apart. Additionally, it is evident that there is a degree of variation in the morphology of animal hairs. The hairs of sheep and rabbits exhibit typical traces of hair growth, namely a progressive layer-by-layer scale-like structure. This structure may be conducive to achieving a smoother writing surface with Chinese brushes. It was unexpected that the hairs of pigs and wolves exhibited notable differences from those of sheep and rabbits. The surface of the hairs of the former exhibits a greater number of coverings, which is not found in the latter. It is postulated that this is due to the fact that pigs and wolves consume a greater quantity of fats and protein-based foods, resulting in the production of more oily secretions on the hair17. It is noteworthy that although this phenomenon was not identified microscopically in ancient China, the experience was documented in ancient texts. For instance, brushes crafted with pigs and wolves were observed to have poor absorbency. This may serve to corroborate our hypothesis.

The ordered structure of animal hair can also be observed using POM. As illustrated in Fig. 2A, when the fibers are positioned within a POM, the polarized light will be transmitted if the fibers possess an ordered structure. Conversely, if the fibers lack an ordered structure, the polarized image will appear black18,19. Also, if the ordered structure exhibits regular alterations, it will result in a shift in the wavelength of the polarized light, thereby creating variations in the hue of the transmitted polarized light. As illustrated in Fig. 2B, the POM image of abutilon exhibits a distinct bright white, which is attributed to the presence of cellulose crystals. In the case of nylon, the orientation of polymer chain segments during processing imparts a characteristic ordered structure, manifesting as a bright white hue in the center. We then compared the POM images of different animal hairs, as shown in Fig. 3. For rabbit and goat, we found scale-like hierarchical structures, and by increasing the magnification of the POM images, we found that the brightness of this polarization was high. We also found that the polarized images of pig and weasel hairs showed various polarized colors. The distinguishing factor between animal hairs is the potential for weasel and pig hair to contain higher concentrations of oils and proteins20,21. POM is designed to identify the presence of oils and fats due to the possibility of chiral characteristics inherent to these compounds22. This chiral feature contributes to the distinctive polarized coloration observed in animal hairs.

In conclusion, the above findings demonstrate that there are notable distinctions between plant fiber, artificial fiber, and animal hair. In comparison to plant fiber and artificial fiber, animal hair exhibits a more discernible hierarchical structure. Additionally, in contrast to the hair of carnivorous wolves and pigs, the hair of herbivorous rabbits and sheep displays a more pronounced hierarchical topology. This observation elucidates the rationale behind the preference of ancient Chinese artists for utilizing the hair of rabbits and sheep as the primary component of the Chinese brush at the microscopic level.

Micromorphology and topography of early Chinese brushes from the 1960s

To ascertain the micromorphology and topology of ancient Chinese brushes, direct examination of these artifacts represents the optimal approach. Nevertheless, it is crucial to acknowledge that the materials utilized in their construction are highly prone to degradation and damage, posing significant challenges to the preservation and dissemination of these ancient brushes. Consequently, the direct observation of brushes dating back thousands of years is unfeasible. Fortunately, however, valuable ancient Chinese brushes from the 1960s have been discovered, affording us the opportunity to scrutinize the micromorphology and topology of earlier brush designs. As shown in Fig. 4, the micromorphology of goat, paguma larvata, and mink hair from these brushes in the 1960s was observed via SEM. Our research has revealed that brushes crafted from goat hair exhibit a distinctly pronounced lamellar scale-mounted morphology. In contrast, brushes made from the hair of paguma larvata and mink display a more diffuse, scale-like appearance. These findings align closely with the characteristics of modern brushes as illustrated in Fig. 1. Furthermore, it is plausible that the hairs of carnivorous and omnivorous animals contain higher levels of oils, which may contribute to the presence of oily secretions on the surface of the brushes. POM is specifically designed to detect the presence of oils and fats, as these compounds may inherently possess chiral properties. This chiral nature facilitates the observation of unique polarized coloration in animal hair. As illustrated in Fig. 5, goat hair exhibits a scale-like layered topology, and upon increasing the magnification of the POM image, we observed a particularly bright polarization. Notably, the polarized images of mink hair demonstrated an exceptionally rich array of polarized colors, suggesting that mink hair possesses chiral characteristics. The distinguishing factor among these three animals is that mink, as a carnivore, may have hair with higher concentrations of oil and protein compared to the others.

Based on the aforementioned findings, we conclude that the characteristics of brushes from the 1960s are fundamentally indistinguishable from those of contemporary brushes. This similarity suggests that a promising approach to studying the writing performance of brushes could involve analyzing the micromorphology and topology of the brush materials. Consequently, it is feasible to pursue further innovative modifications and research endeavors, building upon the foundational knowledge derived from earlier brush designs.

Modification of the PDA layer on the rabbit hair Chinese brush

Brush-ink interaction critically affects Chinese brush art. An effort was made to enhance the interaction between the brush material and ink by modifying the surface properties of the brush material. PDA modification is a process that involves a mild reaction and is employed for the purpose of modifying brushes. The use of brushes crafted from different materials will inevitably result in disparate writing experiences. Consequently, we have elected to focus our subsequent discussion on the more commonly utilized rabbit hair Chinese brush. PDA exhibits excellent adhesion properties and is capable of adhering effectively to hair. To ascertain the efficacy of PDA modification, we employed FTIR to characterize the brush before and after modification. As shown in Fig. 6A, in comparison to the FTIR spectrum of the rabbit hair Chinese brush, the PDA-modified brush exhibited a markedly distinct signal at 1630 cm−1, which was postulated to be ascribed to the C–N bond23,24. The oxidative self-polymerization of PDA produces a variety of reaction products, including quinone and anthracene structures, which contain the C–N bond. Therefore, it can be reasonably concluded that PDA has been successfully modified on rabbit hair. To substantiate the impact of the PDA modification on the rabbit hair’s scaly ordered structure, we conducted a comparative analysis of polarized light transmission before and after the modification using POM, as shown in Fig. 6B. The unmodified rabbit hair exhibits a scale-like anisotropic structure, which is consistent with previous observations. The POM images of the PDA-modified brush revealed the presence of gray-black layered structures on the fiber, thereby corroborating the successful modification of the PDA layer. Concurrently, the hair exhibited a bright white color, indicating that the PDA modification did not disrupt its ordered structure.

Water absorption and writing performance of PDA-modified Chinese brush

To further reflect the changes in the ink-absorbent properties of the PDA-modified brushes, the ink (RedStar Ink, Anhui, China) was selected for testing different brushes. The brushes were fully impregnated, as illustrated in Fig. 7A. Thereafter, the brushes were lifted and the ink dripping from them was monitored in real time, with the mass lost from each brush recorded. Following the completion of the drops, it was observed that the morphology of the various brushes exhibited notable discrepancies. In comparison to the narrow and thin nibs of the rabbit hair Chinese brush, the PDA-modified Chinese brush exhibited thicker nibs, which may indicate a greater retention of ink in the PDA-modified brush. As illustrated in Fig. 7B, the loss of the wrapped ink can be classified into three distinct phases. The initial stage is characterized by a rapid loss of ink, which is attributed to the self-weight of the ink causing rapid dripping. The second stage of ink mass loss is characterized by a deceleration in the rate of loss, which can be attributed to two factors: the reduction in the weight of the ink and the ability of the quill to extract a portion of the ink, thereby concentrating it at the nib. The third stage is the stabilization stage, which indicates that the interaction between the ink and the brush is balanced and that no further drops will occur due to gravity. In the actual creative process, the artist will maintain the ink in the brush during the second and third stages to facilitate a controlled creative process. It is evident that the rate of ink loss in brushes composed of pure rabbit hair is greater than that observed in brushes modified with PDA. Additionally, the term α is defined as the mass ratio of lost ink mass to the total ink mass. Following the third stage, the α value of the rabbit hair Chinese brush is approximately 10.9%, whereas that of the PDA-modified Chinese brush is 6.5%. This indicates that the PDA-modified brushes can retain a greater quantity of ink during the creation process. This is particularly crucial for the creative process, as the depletion of ink can impede the artist’s ability to express themselves artistically.

The interaction of the brushes with ink was tested, and it was found that PDA has a favorable effect on the retention of ink in the brushes. It remains to be seen whether this property can be harnessed in artistic creation; thus, we evaluated modified Chinese brushes for their suitability for actual creation. As illustrated in Fig. 8A, B, to guarantee the uniformity and repeatability of the examination, the three identical artists selected the identical ink to write or draw upon the identical paper. In order to gain a full understanding of the Chinese character “一,” it is essential to pay close attention to the three distinct parts that comprise it. The initial point of focus is at the juncture where the strokes converge. The second point of interest is at the center, and the final point of focus is at the point where the strokes terminate. The point at which the brush is applied is of a greater thickness, and the writing is clear and firm due to the presence of a substantial quantity of ink. At the center, the brush must be dragged; the unmodified rabbit hair Chinese brush has a very light ink that does not close the nib quickly enough when lifting the brush, resulting in the observed wide spacing. In contrast, the character “一” written with a PDA-modified brush exhibits thicker ink and narrower spacing at the center. This indicates that the brush can respond rapidly to the lifting action of the brush. Furthermore, the closing part of the brush at the end also demonstrates a discernible contrast, with the PDA-modified brush exhibiting a greater retention of ink and a thicker ink stroke. Additionally, a more precise and defined stroke was discerned in the creative output of the PDA-modified brush, which exhibited a notable contrast to the unmodified brush. Subsequently, we employed a PDA-modified Chinese brush to reproduce calligraphic works and generate Chinese paintings, as illustrated in Fig. 8C. The use of a PDA-modified brush allows for the creation of both bold and fine Chinese characters. Concurrently, the bamboo exemplifies a three-dimensional and interlaced meaning through the robust water absorption capacity of the brush. In conclusion, this study presents a novel approach to brush modification, with the potential for PDA-modified brushes to be utilized in the creation of Chinese calligraphy and landscape painting.

Discussion

The relationship between brush and writing performances is rarely considered from the perspective of modern experimental science, particularly when it is differentiated and discussed in the context of the microscopic morphology of the material. In this study, we initially examined the provenance of the diverse range of bristle materials, encompassing abutilon fiber, man-made nylon fiber, and animal hairs, which were subjected to a systematic elaboration process. Subsequently, based on observations conducted using SEM and POM, it was further revealed that animal hair has a microscopic multilayered structure, which facilitates the smoothness of the writing process. Additionally, it is important to acknowledge the considerable morphological diversity observed among different animal hairs. In particular, the hairs of carnivorous animals will have a greater concentration of oily substances, which is not conducive to their ability to encapsulate ink. The hairs of herbivores, such as sheep and rabbits, exhibit a superior layered structure and a reduced level of grease, which provides an explanation for the microscopic level at which rabbit hair has become a popular material for brushes. Ultimately, we proceeded to modify the rabbit hair brush based on these findings, with the objective of developing a new brush that would exhibit enhanced writing and drawing properties. By employing a straightforward oxidative self-polymerization process, we successfully synthesized PDA-modified Chinese brush. The incorporation of PDA markedly enhanced the ink absorption capacity of the rabbit hair brush, exhibiting a remarkable degree of responsiveness and ink adsorption stability during the writing of Chinese characters. Our results link brush materials to writing performance. The PDA modification method is efficient and practical. It may guide future brush production.

A subsequent presentation of this study will be offered from an artistic and historical-cultural perspective. This study begins with an examination of the correlation between the Tang and Song brush systems and calligraphic styles. It then proceeds to investigate how the PDA of the brush hairs can be modified from an interdisciplinary perspective, with the aid of the methodology of material science in science and technology disciplines. The objective is to enhance the adhesion of the brushes to the ink, thereby improving the ink storage capacity of the brushes and maximizing their corroboration with the ancient art literature. Following comprehensive argumentation and rigorous experimentation, it can be posited that the modified brush hair exhibits three novel characteristics when writing. Firstly, the adsorption between the brush hair and the ink is stronger, resulting in a fuller shape of the brush head after dipping into the ink, which is more conducive to the completion of rich dotting patterns. Secondly, the enhanced ink storage capacity allows for a slower writing time, which facilitates the execution of delicate strokes such as lifting and pressing, twisting and turning, as well as the delineation of dot and line beginnings and ends. This enables the writer to more effectively express their creative intent. Thirdly, this experiment and the ancient literature on the performance of the brush are mutually referential. That is to say, the ancient writers on the writing process of the brush, in order to grasp the performance of the brush, called the brush properties, refer to the experiment, which shows that the modernization of the means can effectively improve the characteristics of the brush, strengthen the flexibility of the brush, and revolutionize the old cumbersome process of making brushes. In general, the experiments demonstrated that the ink storage capacity of the brush hair was significantly enhanced, the writing time was effectively slowed down, and a new path was explored to revolutionize the ancient, cumbersome brush-making process, including the handling of the hair material.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Wang, Q., Meng, Q., Liu, H. & Jiang, L. Chinese brushes: from controllable liquid manipulation to template-free printing microlines. Nano Res. 8, 97–105 (2015).

Liu, Z. & Liu, K. Reproducing ancient Chinese ink depending on gelatin/chitosan and modern experimental methodology. Herit. Sci. 10, 110 (2022).

Hu, Q. et al. Sgrgan: sketch-guided restoration for traditional Chinese landscape paintings. Herit. Sci. 12, 163 (2024).

Han, Y., Li, X. & Fu, C. Origins of Chinese Culture (Asiapac Books Pte Ltd, 2005).

Qiu, Z. Form and Interpretation of Calligraphy (Chongqing Publishing House, 1993).

Zhu, Y. History of books: the Pen Maker” written by the Qing and Liang Dynasties. Lit. Life 7, 26–32 (2011).

Wang, Q., Su, B., Liu, H. & Jiang, L. Liquid transfer: Chinese Brushes: controllable liquid transfer in ratchet conical hairs. Adv. Mater. 26, 4888–4888 (2014).

Chen, C.-T., Martin-Martinez, F. J., Jung, G. S. & Buehler, M. J. Polydopamine and eumelanin molecular structures investigated with ab initio calculations. Chem. Sci. 8, 1631–1641 (2017).

Zhang, X. et al. Mussel-inspired fabrication of functional materials and their environmental applications: progress and prospects. Appl. Mater. Today 7, 222–238 (2017).

Micillo, R. et al. Eumelanin broadband absorption develops from aggregation-modulated chromophore interactions under structural and redox control. Sci. Rep. 7, 41532 (2017).

Jiang, C. Application Techniques of Chinese Painting Materials (Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 1999).

Li, C. Words and Notes (Jinan Publishing House, 1999).

Fode, T. A., Chande Jande, Y. A. & Kivevele, T. Physical, mechanical, and durability properties of concrete containing different waste synthetic fibers for green environment—a critical review. Heliyon 10, e32950 (2024).

Lim, J. G., Gupta, B. S. & George, W. The potential for high performance fiber from nylon 6. Prog. Polym. Sci. 14, 763–809 (1989).

Chawla, R. & Fang, Z. Hemp macromolecules: crafting sustainable solutions for food and packaging innovation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 273, 132823 (2024).

Altman, A. W. et al. Review: Utilizing industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) by-products in livestock rations. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 307, 115850 (2024).

Mu, Yan. & Si, Mao. Top ten famous pens in China. 360Doc Library in Beijing. http://www.360doc.com/content/23/0302/13/29378424_1070114781 (2023).

Ascenzi, M.-G. Theoretical mathematics, polarized light microscopy and computational models in healthy and pathological bone. Bone 134, 115295 (2020).

Keefe, D., Liu, L., Wang, W. & Silva, C. Imaging meiotic spindles by polarization light microscopy: principles and applications to IVF. Reprod. BioMed. Online 7, 24–29 (2003).

Bouligand, Y. Twisted fibrous arrangements in biological materials and cholesteric mesophases. Tissue Cell 4, 189–217 (1972).

Chou, S. C., Cheung, L. & Meyer, R. B. Effects of a magnetic field on the optical transmission in cholesteric liquid crystals. Solid State Commun. 11, 977–981 (1972).

Forbes, R. E., Everatt, K. T., Spong, G. & Kerley, G. I. H. Diet responses of two apex carnivores (lions and leopards) to wild prey depletion and livestock availability. Biol. Conserv. 292, 110542 (2024).

Kral, M. et al. Nano-FTIR spectroscopy of surface confluent polydopamine films – What is the role of deposition time and substrate material?. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 235, 113769 (2024).

Kashi, M., Nazarpak, M. H., Nourmohammadi, J. & Moztarzadeh, F. Study the effect of different concentrations of polydopamine as a secure and bioactive crosslinker on dual crosslinking of oxidized alginate and gelatin wound dressings. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 277, 134199 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund Art Project (Project Name: Compilation and Research of Su Shi’s Calligraphy and Inscription Documents, No.: 24BF107), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Project Name: Documentation and Research on Su Shi’s Calligraphy and Inscriptions, No.: 23JNQMX59).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhen Liu and Kun Liu wrote the main manuscript text, prepared figures, and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Z., Liu, K. Analyzing the intrinsic connection between Chinese calligraphy creation and brush properties from a micro perspective. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 415 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02005-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02005-1