Abstract

Chipped stone tools can reveal past human activities and movements, but have received less attention than ground stone tools in studies of early farming societies in China. This study addresses this gap by examining quartz chipped stone tools from Jiahu, one of the earliest farming communities in Central China. Apart from typo-technological analysis, experimental archaeology was employed to replicate quartz cores and flakes using similar raw materials, shedding light on the knapping techniques used at Jiahu and evaluating the functional potential of the tools. Combined with a preliminary use-wear study, the results suggest that this quartz assemblage likely played a role in Neolithic craft production. These findings provide valuable data for future comparative research on technological choices across early agricultural societies, thereby contributing to deeper investigations into the origins and development of the earliest farming communities in Central China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

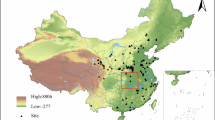

Early farming societies reshaped human history by driving agriculture, settlement, and civilisation, making them a central focus of archaeological research. This paper conducts the case study at the Neolithic site of Jiahu (7000–5500 BC) in Central China (Fig. 1), an area often regarded as a cradle of Chinese civilisation. Jiahu is notably recognised for having yielded some of the earliest evidence of rice cultivation1,2, animal domestication3,4, and use of ground stone tools5,6,7, indicating that the Jiahu inhabitants were the first rice farmers in China’s central plains8.

Map showing the locations of the Neolithic sites of Jiahu (with rice remains), Lingjing, Tanghu (with rice and millet remains) Xiaohuangshan and Shangshan (with rice remains), the map is modified from Fig. 1a in (Li et al. 2020).

In addition to agricultural remains, a range of archaeological findings at Jiahu demonstrate significant innovation, such as the production of playable bone flutes9, the production of fermented beverages10, and the development of proto-writing symbols11. Despite the substantial impact of the Jiahu inhabitants on the advent of agricultural and cultural practices, the exact origins of this early farming community in Central China have yet to be determined.

One hypothesis suggests that the population at Jiahu may have originated from southeastern China, a region later pivotal in the emergence of rice agriculture12,13,14. Following the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, ~26,500–19,000 BP), the persistent rise in sea levels substantially altered the southeastern coastal landscape15. These environmental changes may have gradually prompted the relocation of coastal populations into inland regions over the long term. This migration theory not only accounts for the early practice of rice agriculture observed at Jiahu from the onset of the site’s occupation, but also elucidates the observed similarities in the pottery assemblages between Jiahu and Neolithic sites in Southeast China8. Despite these correlations, direct evidence linking the Neolithic populations of Jiahu with those of Southeast China remains absent.

To tackle the question of population migrations in the Neolithic, although genetic analysis (e.g., ancient DNA) is one of the most powerful tools16,17, human remains from Southeast China are often poorly preserved. In addition, human skeletons unearthed at the site of Jiahu were analysed, but no genetic material was successfully extracted. In this scenario, material culture and other archaeological evidence hold the potential to reconstruct past human activities and movements.

Previously at Jiahu, the ground stone tools and pottery vessels have already been classified and analysed through various methods, providing strong evidence for comparing Jiahu culture with other Neolithic cultures in China5,6,8,18,19. Notably, although chipped stone tools are more commonly associated with hunter-gatherer societies, they continued to be used by the Jiahu people and other early farmers in Neolithic China20. Despite their potential to provide crucial insights into technological choices, raw material procurement, and possible cultural connections with earlier populations, the chipped stone tools recovered from the site have received relatively little attention compared to ground stone tools20,21,22,23. Thus, this study attempts to analyse the chipped stone tools unearthed at the Jiahu to better understand their roles, provide complementary evidence for comparing Neolithic cultures in China, and offer further insights into past population movements.

For the study of chipped stone tools from Jiahu, we present a unique multidisciplinary methodology applying classical technological and typological analyses24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. Additionally, experiments were conducted to replicate quartz tools like those found in the Jiahu assemblage, aiming to understand how they were made. The experimentally produced artefacts were then used to perform various tasks to assess their efficiency (Fig. 3), which allowed for further inferences regarding their potential functions.

Thus, the quartz-based chipped stone artefacts from Jiahu presented herein offer essential empirical material for further comparative analyses. This dataset is hypothesised to be instrumental in revealing potential inter-populational connections or migratory routes through comparisons with earlier regional and Southeast Chinese assemblages (Fig. 1), based on the premise that quartz tool production technology reflects cultural continuity or divergence, thereby illuminating prehistoric technological traditions and mobility.

Methods

Study materials

During the first six excavation seasons (1983–1987), 1147 lithics were documented and subjected to systematic categorisation, resulting in the identification of four principal artefact groups18.

Specifically, the first group encompasses non-modified lithic raw materials designated for tool production (manuports), as well as preliminary stone products indicative of the initial stages of the tool-making processes. The second group comprises implements such as hammers, used in the manufacture of other stone tool types, reflecting a secondary level of tool production. The third group consists of stone tools directly associated with agricultural practices or food-processing activities, The third group consists of stone tools likely associated with agricultural practices, food-processing activities, or craft production, including polished stone shovels, sickles, knives, axes, adzes, chisels, and grinding tools, stone balls, and spinning wheels, which signify the employment of lithic technology in subsistence strategies. The fourth group is composed of ornamental items and miscellaneous artefacts that do not align with the previously defined categories, including a diverse range of non-utilitarian and potentially symbolic objects (e.g., turquoise beads found in graves).

In addition, various types of lithic raw materials have been identified in the toolkits18, demonstrating that the Jiahu people utilised a wide range of materials (Fig. S1). In the recent excavation seasons (2009 and 2013), Jiahu yielded more artefacts pending further detailed studies32,33.

Building upon previous archaeological findings at Jiahu, this paper focuses on chipped stone tools made of quartz, as they were ubiquitous at the site and throughout the surrounding region. Furthermore, it has been observed that some quartz artefacts from Jiahu exhibit distinctive physical properties (e.g., the relative resistance of their cutting edges, Fig. 3), which hold great potential to provide new insights into why quartz played such a pivotal role in many Palaeolithic and Neolithic communities in China34,35,36.

The archaeological quartz stones presented in this study comprise 160 specimens from Jiahu, including 135 pieces unearthed during the excavations conducted in 2009 and 2013, and 25 specimens retrieved from the initial six excavation seasons spanning 1983 to 1987 (Table S1). Except for one quartzite artefact, all the items studied are made from quartz (Table S2). The artefacts were documented using digital photography with a Nikon D780 camera equipped with a Nikon AF-S DX Micro NIKKOR 40 mm f/2.8G lens.

Typo-technological analysis

Lithic technology encompasses the production and utilisation of stone tools and constitutes a fundamental component of archaeological and anthropological research. It yields profound insights into the behaviours, lifestyles, and technological progression of early humans and their predecessors37,38.

The selected artefacts for the current study underwent a systematic classification based on their technological attributes and tool typology. Tailored parameters were meticulously chosen for each category (Table S3). The definition of stone reduction operative chains was determined based on the specific flake and debris attributes (Table S3). Core types and knapping strategies were determined based on diacritical analyses, bringing to light the gestural sequencing involved in the knapping processes.

Experimental archaeology

Knapping experiments were conducted to replicate the quartz cores and flakes, employing both bipolar-on-anvil and freehand knapping methods (Fig. 2) following previous interpretations and personal observations18. The primary objective of these experiments was to discern the most efficient method for producing cores and flakes akin to those unearthed at the site of Jiahu. The selection of raw materials used for the experiments was guided by archaeological evidence from Jiahu, where sandstones predominantly served as anvils, with dimensions mirroring those unearthed at the site18. Furthermore, archaeological hammerstones, typically fashioned from repurposed broken axes or grinding rollers, were identified as essential components of the knapping toolkit.

Flakes (c, e, and g) produced using freehand knapping (a) and the bipolar-on-anvil method (b), displaying similarities to artefacts from the Jiahu site (d, f, and h) (note: c and d exhibit broad dorsal surfaces and appear to be thicker, with signs that they have been used as cores for further flake removal; both e and f have well-developed platforms at the bottom and thin, sharp distal edges; both g and h have a roughly triangular shape, with a clear platform at the base and pointed distal ends the flake morphologies of e and f are relatively regular, and they could be served as functional cutting edges).

For the experiments, hammerstones—relatively small, ranging from 5 to 10 cm—were sourced from the Francolí River Valley in Tarragona, Spain. The sandstone used as the anvil material was sourced from the Mella River, in the village of Castel Mella in Brescia (Italy). Quartz stones procured from alluvial terraces in Tautavel (France) constituted the raw material for the knapping experiments. All knapping experiments were conducted in an open-air setting proximate to the Catalan Institute of Human Palaeoecology and Social Evolution (IPHES-CERCA) in Tarragona (Spain).

After the knapping sessions, the efficacy of the produced flakes was evaluated through practical application on fresh chicken legs procured from a local supermarket in Spain (Fig. 3). Specifically, a flake (Exp-JH 1) featuring a sharp edge was employed for cutting and deboning chicken meat, followed by the utilisation of another sharp-edged flake (Exp-JH 2) to scrape residual meat from the chicken legs. Subsequently, a flake (Exp-JH 3) with a sharp edge was utilised for bone cutting, while a pointed flake (Exp-JH 4) served for drilling holes in the chicken bone. These tasks were performed with careful attention to detail by the primary author, with documentation of the time required to complete each task (Table S4). In this study, quartz was selected for bone processing experiments to assess its feasibility as a material for manufacturing ‘bone flutes’, given that such artefacts have been unearthed at Jiahu. It is worth noting that previous studies have also employed quartz tools to process various materials, including animal soft tissue, fresh hide, herbaceous plants, tubers, and wood39,40.

Experiments utilizing quartz flakes (e–h) for processing chicken meat and bone (a: cutting meat with flake e; b: scraping meat with flake f; c: cutting bone with flake g; d: drilling bone with flake h; i–l: Broken flakes from Jiahu exhibiting similar fracture patterns observed on the experimentally utilized flakes, the used portions of the experimental flakes are indicated with white lines and the fracture areas of the experimental and archaeological flakes are marked with red lines).

Microscopic observation

Functional studies and experimental programmes focusing on quartz are relatively scarce in the scientific literature, with notable exceptions41,42. This is because quartz has historically been perceived as challenging for functional analysis due to its inherent characteristics, including irregular fracturing patterns, surface texture, high reflectivity, and hardness43.

In this study, we initiated our examination by specifically selecting quartz artefacts from the Jiahu site that exhibited pointed or sharp edges for further microscopic observation. Utilising magnifications ranging from 21X to 60X, we meticulously scrutinised these artefacts to identify observable use-wear features, mainly focusing on fractures and edge rounding. The primary aim of this endeavour was to ascertain the potential functional roles of these artefacts in ancient activities, providing a reference that can, in the future, serve to obtain a more nuanced understanding of their archaeological significance.

Results

Technological analysis

The quartz cores recovered from the Jiahu site, a crucial assemblage for understanding early lithic technology in the region, present a consistent yet varied picture of reduction strategies focused on the production of small flakes. The 32 analysed cores exhibit a relatively constrained average size of 41.5 × 37.5 × 25.7 mm (Table S5), with a weight distribution spanning a considerable range from a mere 1.8 grams to a substantial 301 grams (mean weight: 60.3 grams). This suggests a flexible approach to raw material utilisation, potentially adapting to the size and form of available quartz nodules.

Most of these cores (Fig. 4) bear evidence of moderate reduction intensity, displaying between 3 and 8 discernible flake removals (mean: 4.62 negatives, Table S5). Notably, the diminutive size of the resulting flake scars, averaging 23.3 × 17.9 mm along the knapping axis (Table S5), strongly indicates a deliberate and consistent effort towards the production of small, potentially standardised flakes at the site. This focus on small flake production has implications for understanding the intended function of the resulting tools, possibly geared towards tasks requiring precision or the processing of specific materials.

a Example of a core with five clear removals; b Example of a core with four clear removals; c Example of a core with three clear removals. Note: the white arrows indicate the directions of removals and the numbers indicate the sequences, where applicable, the removals were outlined with thin blue lines.

Our analysis reveals that these cores were predominantly shaped using multifacial multipolar knapping techniques, a strategy allowing for the exploitation of the raw material from multiple angles. Intriguingly, we also identified instances of bifacial orthogonal knapping on an anvil (Table S2), suggesting a diverse toolkit of knapping methods employed by the Jiahu knappers.

Of particular interest is the clear evidence for controlled bipolar-on-anvil knapping on a subset of cores (n = 5). These specimens exhibit diagnostic features – opposing impact points and characteristic crush marks – which were independently verified through our experimental replication studies. The presence of this more specialised technique alongside other methods underscores a nuanced understanding of quartz fracture mechanics and a deliberate selection of appropriate knapping strategies. The measured flake extraction angles, ranging from 55 to 110 degrees (mean: 87.5 degrees), further support the inference of controlled and varied knapping actions aimed at producing flakes of specific dimensions and potentially with specific edge characteristics.

A significant aspect of the Jiahu lithic technology is the presence of 24 cores-on-flakes within the flake assemblage (n = 86), representing a resourceful strategy for maximising raw material utilisation. These re-knapped flakes exhibit evidence of limited but deliberate secondary reduction, displaying between one and seven removals (average: 2 removals per core; Fig. 5). This pattern suggests a targeted effort to either rejuvenate the edges of larger primary flakes or to produce a small number of additional, potentially specialised flakes. The notable proportion of these cores-on-flakes underscores a technological emphasis on the efficient exploitation of the abundant primary flake production at Jiahu, which predominantly yielded non-cortical flakes. Rather than discarding these larger flakes, the knappers at Jiahu strategically repurposed them as cores, demonstrating an economical approach to lithic resource management and the potential for creating expedient tools or maintaining existing ones.

The assemblage of whole quartz flakes (n = 64) from Jiahu provides key insights into the final stages of core reduction and the nature of the intended end-products. These flakes exhibit modest average dimensions (33.6 × 24.8 × 11.9 mm, Table S6) and weight (mean: 15.42 g), a size profile consistent with the reduction intensity observed on the associated cores (Fig. 6), suggesting a targeted production of relatively small flakes.

Analysis of cortical residue on the dorsal surfaces and butts of these flakes, categorised according to Toth’s (1985) typology (Types I-VI, Table S6), allows us to reconstruct the operational sequences employed at the site. The scarcity of fully cortical flakes (Type I, 4.7%) and those with cortical butts and partially cortical dorsal surfaces (Type II, 3.1%) indicates that initial core opening and primary shaping were not the dominant activities represented in this analysed flake sample.

In contrast, flakes with either a cortical butt and non-cortical dorsal surface (Type III, 12.5%) or a non-cortical butt and fully cortical dorsal surface (Type IV, 9.4%) are slightly more prevalent, suggesting later stages of decortication or the exploitation of partially decorticated cores. A more substantial proportion of the assemblage comprises flakes with a non-cortical butt and partially cortical dorsal surface (Type V, 23.4%), indicating sustained reduction of cores with remaining cortical areas.

Strikingly, nearly half of the analysed flake assemblage (Type VI, 46.9%) consists of completely non-cortical flakes. This dominance strongly underscores a significant focus on the production of secondary and tertiary flakes, derived from well-prepared cores. Indeed, the combined frequency of non-cortical (Types IV, V, and VI) flakes (79.7%) highlights a technological strategy centred on repeated flake removals from previously established striking platforms and frequent core rotation, a pattern particularly evident in the multifacial cores (Table S2). The presence of cortex on the lateral or dorsal edges of both cortical and non-cortical platform flakes (Types II and V) further suggests the systematic reduction of relatively small, potentially irregular cores or the strategic utilisation of remaining cortical edges for flake detachment.

The analysis of 21 broken flakes (average dimensions: 25.6 × 19.2 × 8.9 mm, Table S7) confirms that they originate from intentional removals, evidenced by the presence of diagnostic ventral and dorsal surfaces, discernible platforms, and impact points. Fractures predominantly occur along the lateral or distal edges (Fig. 3), suggesting potential use-related breakage or post-detachment damage.

The associated debris (n = 19), defined here as fragments lacking clear impact points, striking platforms, or discernible ventral surfaces. A subset of these fragments exhibits proximal fractures, raising the possibility that they represent highly fragmented flakes where key diagnostic features have been obliterated, further indicating significant fragmentation of knapping products.

Crucially, the refitting of a broken flake onto a broken core excavated from the same burial context (M489) provides direct and compelling evidence for on-site lithic reduction activities. This physical link, coupled with the prevalence of small-sized debris consistent with knapping byproducts, unequivocally demonstrates that quartz tool production occurred within or immediately adjacent to the burial context, offering a rare spatial association between lithic technology and funerary practices at the Jiahu site.

Within the Jiahu quartz assemblage, 34 specimens exhibit morphological characteristics indicative of intentional tool manufacture and potential utilisation (Fig. 7). This subset is defined by the presence of deliberately shaped thin edges (n = 10), semi-thick edges (n = 15), or pointed terminations (n = 9), suggesting a targeted design for specific tasks. The presence of these distinct edge morphologies implies a functional differentiation within the lithic toolkit. For example, pointed artefacts are consistent with tools intended for piercing or drilling, while those with thin or semi-thick edges are morphologically suited for cutting or scraping activities. These functional inferences, based on macroscopic morphology, are further supported by evidence derived from our experimental replication studies and high-magnification use-wear analysis (detailed below), providing a multi-faceted understanding of the functional versatility inherent in these quartz implements.

a Jiahu 82 displaying a pointed head and distinct use-wear traces, including striations and reflective polish; b Jiahu 75 featuring a sharp point; c–f are Jiahu 64, Jiahu 60, Jiahu 112, and Jiahu 122 accordingly, exhibiting fractures on their edges, likely resulting from cutting or scraping activities, scale bar: 1 mm.

Insights from experimental archaeology

Experimental replication of quartz knapping techniques yielded distinct outcomes relevant to understanding the Jiahu lithic assemblage. Freehand knapping of small quartz clasts proved inefficient, particularly in initiating core reduction and maintaining knapping continuity as core size decreased. This method’s limitations highlight its potential unsuitability for consistent and precise flake production, especially when dealing with diminutive raw material.

In stark contrast, the bipolar-on-anvil technique demonstrated remarkable efficiency in processing quartz cores, consistently producing flakes morphologically similar to those recovered from the Jiahu site (Fig. 2). This method effectively initiated core reduction and maintained productivity even with diminishing core size, underscoring its potential as a primary reduction strategy at Jiahu. The near-identical characteristics of the experimentally produced flakes lend strong support to the inference that bipolar knapping was a significant technological component at the archaeological site.

Building upon the established potential of quartz tools for cutting tasks due to their high hardness and resistance44,45, functional experiments using replicated quartz flakes—including cutting and scraping meat, cutting bone, and drilling bone surfaces (Fig. 3)—confirmed their suitability for a range of activities (Table S4). These results validate the potential multifunctionality of the Jiahu quartz flake assemblage, suggesting their practical applicability in diverse tasks, including craft production such as the creation of bone flutes.

Notably, while the experimental flakes exhibited overall efficacy, breakage occurred during meat scraping and bone cutting. Strikingly, the patterns of these experimental fractures closely mirrored those observed in the archaeological broken flake assemblage (Fig. 2). This direct morphological correspondence provides compelling experimental evidence suggesting that analogous mechanical stresses during utilisation may have resulted in the breakage patterns documented on the Jiahu quartz flakes.

Microscopic observation

Initial low-magnification microscopic analysis (≤100X) of 15 artefacts with pointed tips or thin edges provides compelling evidence for their utilisation (Fig. 7). Notably, a fractured pointed tool (Jiahu 82, Fig. 7a) exhibits distinct use-wear traces concentrated at its apex, including the presence of striations and reflective polish, indicative of contact with worked materials. Fractures observed on artefacts with thin edges are visible at both low (30X, Figs. 7c and 7d) and slightly higher magnifications (60X, e.g., Fig. 7e and f). Given the absence of macroscopic retouch on these tools, these use-wear patterns suggest a rapid and expedient utilisation of small-sized quartz flakes for immediate tasks. The presence of clear use-wear on these unretouched edges underscores the efficiency and direct application of even minimally modified flakes in the Jiahu lithic technology.

Discussion

Previous studies of stone artefacts from the initial six excavation seasons at the Jiahu site (while not focused specifically on chipped stones) have indicated that both freehand and bipolar-on-anvil knapping methods were used in the manufacture of chipped stone tools18. Notably, it has been observed that materials other than quartz were predominantly processed using freehand knapping, while quartz was exclusively handled using the bipolar-on-anvil method to produce flakes. Additionally, it has been suggested that Jiahu cores associated with freehand knapping can be categorised into single-platform and multi-platform cores, predominantly crafted from sandstone, which were often employed in the production of scrapers and larger flakes compared to those made from quartz.

These observations, combined with our new findings from the study of quartz stones presented here, contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of lithic reduction methods employed at Jiahu. Specifically, the use of the bipolar-on-anvil method for quartz stones is now confirmed by our experimental work, indicating distinct technological strategies employed by the Jiahu inhabitants for different materials. Furthermore, despite the quartz flakes being rather small and lacking retouch, experimental and microscopic analysis have revealed that the Jiahu quartz chipped stone tools likely served different purposes.

At the Neolithic site of Shangshan (around 8000–6200 BC) in southeast China (Fig. 1), where early rice agriculture evidence exists46, a typological analysis was conducted on 1,709 chipped stone tools47. Raw materials at Shangshan include diorite, rhomb porphyry, tuff, sandstone, phyllite, siliceous rock, flint, granite, diorite, basalt, and quartzite. The predominant tool type at Shangshan is flakes (n = 1441), followed by tools (n = 234) and cores (n = 34).

When comparing the lithic assemblages from Shangshan and Jiahu, excluding quartz artefacts, several similarities emerge. For instance, cores from both sites can be categorised into groups resembling those associated with freehand knapping at Jiahu. Additionally, scrapers and utilised flakes are prominent tool types at both sites. Furthermore, it is noted that fine-grained sandstones at both Jiahu and Shangshan are typically processed using freehand knapping techniques to produce stone tools like scrapers, while relatively coarse-grained conglomerate and quartzite are utilised for heavier artefacts such as hammerstones and stone balls. However, these similar technical/typological elements detected at two different sites, more than 500 km from each other, could be a question of technological convergence, not necessarily implying direct cultural relations.

Regarding the dimensions of the Shangshan cores (n = 21), with an average length of 63.5 × 58.68 mm, and thickness of 37.73 mm, exceed those of the Jiahu quartz cores (Table S8, Fig. 8). Similarly, the Shangshan flakes, with an average size of 63.5 × 62.5 × 36.1 mm, generally surpass the average dimensions of the Jiahu flakes (33.8 × 24.4 × 12.1 mm, table S8). Additionally, at Shangshan, quartz flakes were absent, and only one pointed tool was reported (out of 234 pieces). These distinctions underscore the unique nature of the quartz artefact assemblage at Jiahu, setting it apart from the chipped stone assemblage at Shangshan.

In terms of the function of the Shangshan flakes, a study based on use-wear, phytolith, and starch grain analysis has shown that Shangshan flakes with mechanical edge modifications (n = 38) were likely used for harvesting rice48. So far, the Jiahu flakes have not been subjected to detailed functional studies. Nevertheless, for the craft manufacturing at Jiahu, artefacts including bone flutes, turquoise beads, ivory blades, and various bone tools such as needles and spears require the drilling of holes.

To explore the functional capabilities of Jiahu quartz flakes, particularly in the context of craft manufacturing of bone objects, our experiments (Fig. 3) and initial microscopic observations indicate that quartz flakes are effective tools for tasks involving the processing of meat adhering to bones, as well as for cutting and drilling small holes in bone material. Specifically, when applied to chicken bones, quartz flakes were found to accomplish these tasks efficiently, implying a potential role for Jiahu quartz flakes in the manufacturing of bone flutes. However, this proposition needs further investigation, including extensive experimentation with different worked materials (Table S4) and use-wear analysis with high-magnification techniques (work in progress).

Notably, the use of quartz at the Jiahu archaeological site was not an isolated phenomenon within the broader research region. Evidence reveals that throughout the Palaeolithic, quartz emerged as the predominant material utilised in stone tool fabrication, constituting a staggering 95,92% of the inventory at the site of Lingjing (125–90 Ka BP)34. Despite lingering uncertainties surrounding the functional purposes of the quartz artefacts unearthed at Lingjing, typologies such as scrapers, notches, denticulated implements, and pointed tools suggest a divergence from agricultural pursuits due to their much earlier ages.

Conversely, investigations at the site of Tanghu (7000 to 5000 BC) near Jiahu, characterised by a more recent chronology, corroborate the prevalence of quartz flakes. In contrast to the rice farming observed at Jiahu, the inhabitants of Tanghu were engaged in a mixed farming of rice and millet (Fig. 1, Zhang et al. 2012). Consequently, it can be proposed that the pervasive use of quartz across disparate temporal and agricultural contexts within the research region of Jiahu transcends temporal and agrarian constraints. Rather, it probably reflects the abundant availability of the material and its inherent utility across a spectrum of activities.

To summarise, the typological analysis of the Jiahu quartz chipped stone assemblage presented here reveals critical insights into lithic production strategies and tool use within the earliest rice farming society in Central China. Quartz core reduction at the site reflects a consistent knapping strategy aimed at producing small flakes. While a high degree of cortical removal was observed, this may be more indicative of extended use and possible re-use of cores rather than inherently complex technology, especially given the lack of core preparation and the overall simplicity of the knapping concept. The prevalence of flakes derived from non-cortical cores and the strategic production of cores-on-flakes highlight efficient raw material utilisation and potential tool curation practices. Furthermore, the identification of artefacts with thin edges or points, corroborated by microscopic use-wear, suggests the manufacture of specialised tools for specific tasks, including those potentially related to the site’s renowned craft industries.

Comparative analysis with Neolithic sites in Southeast China reveals a distinct character in the Jiahu quartz assemblage, suggesting a potentially localised technological tradition adapted to specific resource availability and functional demands, including a likely role in the production of delicate bone artefacts such as flutes. The sustained utilisation of quartz across various periods and agricultural systems in the Jiahu region underscores its consistent value and versatility within the local technological repertoire.

While this study provides a detailed characterization of Jiahu’s quartz lithic technology, further interdisciplinary research, integrating geological sourcing, detailed use-wear analysis at high magnification, and comparative studies with other Neolithic assemblages, is crucial to fully elucidate the origins of the Jiahu population and the precise role of quartz toolkits in the broader context of early agricultural societies and the development of specialized craft production in Neolithic China.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Zhang, J. & Wang, X. Notes on the recent discovery of ancient cultivated rice at Jiahu, Henan Province: A new theory concerning the origin of Oryza japonica in China. Antiquity 72, 897–901 (1998).

Zhao, Z. & Zhang, J. The report of flotation work at the Jiahu site. Kaogu 8, 84–93 (2009).

Zhang, J. & Luo, Y. Restudy of the Pigs’ Bones from the Jiahu Site in Wuyang County, Henan. Archaeology 1, 90–96 (2008).

Cucchi, T., Hulme-Beaman, A., Yuan, J. & Dobney, K. Early Neolithic pig domestication at Jiahu, Henan Province, China: clues from molar shape analyses using geometric morphometric approaches. J. Archaeol. Sci. 38, 11–22 (2011).

Li, W. et al. New insights into the grinding tools used by the earliest farmers in the central plain of China. Quat. Int. 529, 10–17 (2019).

Cui, Q., Zhang, J., Yang, X. & Zhu, Z. The study and significance of stone artifact resource catchments in the Jiahu site, Wuyang, Henan Province. Quat. Sci. 37, 486–497 (2017).

Li, W. et al. Cereal processing technique inferred from use-wear analysis at the Neolithic site of Jiahu, Central China. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 23, 939–945 (2019).

Chi, Z. & Hung, H. C. Jiahu 1: Earliest farmers beyond the Yangtze River. Antiquity 87, 46–63 (2013).

Zhang, J., Harbottle, G., Wang, C. & Kong, Z. Oldest playable musical instruments found at Jiahu early Neolithic site in China. Nature 401, 366–368 (1999).

McGovern, P. E. et al. Fermented beverages of pre- and proto-historic China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 17593–17598 (2004).

Li, X., Harbottle, G., Zhang, J. & Wang, C. The earliest writing? Sign use in the seventh millennium BC at Jiahu, Henan Province, China. Antiquity 77, 31–44 (2003).

Trivers, R. L. et al. Domestication process and domestication rate in rice: Spikelet bases from the Lower Yangtze. Science 323, 1607–1610 (2009).

Fuller, D. Q. Pathways to Asian civilizations: Tracing the origins and spread of rice and rice cultures. Rice 4, 78–92 (2011).

Yang, X. et al. Barnyard grasses were processed with rice around 10000 years ago. Sci. Rep. 5, 1–7 (2015).

Lambeck, K., Rouby, H., Purcell, A., Sun, Y. & Sambridge, M. Sea level and global ice volumes from the Last Glacial Maximum to the Holocene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 15296–15303 (2014).

Jones, M. & Brown, T. Agricultural origins: the evidence of modern and ancient DNA. Holocene 10, 769–776 (2000).

Haak, W. et al. Ancient DNA from European early Neolithic farmers reveals their Near Eastern affinities. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000536 (2010).

Zhang, J. The site report of Jiahu, first edition. Science Press in Beijing. (1999).

Cui, Q. L., Zhang, J. Z. & Yang, Y. Z. Use-wear analysis of the stone tools from the Jiahu site in Wuyang county, Henan province. Acta Anthropol. Sin. 36, 478–498 (2017).

Chen, S. & Yu, P.-L. Early “Neolithics” of China: Variation and evolutionary implications. J. Anthropol. Res. 73, 149–180 (2017).

Schriever, B. A., Taliaferro, M. & Roth, B. J. A tale of two sites: Functional site differentiation and lithic technology during the Late Pithouse period in the Mimbres area of Southwestern New Mexico. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 30, 102–115 (2011).

Andrefsky, W. The analysis of stone tool procurement, production, and maintenance. J. Archaeol. Res. 17, 65–103 (2009).

Stout, D. Stone toolmaking and the evolution of human culture and cognition. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 366, 1050–1059 (2011).

Tixier, J., Inizan, M.-L., Roche, H. Préhistoire de la pierre taillée. (No Title). Diffusion Association for the promotion and dissemination of archaeological knowledge. (1980).

Toth, N. The Oldowan reassessed: a close look at early stone artifacts. J. Archaeol. Sci. (1985).

Carbonell, E. et al. New elements of the logical analytic system. Cah. Noir 6, 5–61 (1992).

Preysler, J. B. & Monteagudo, F. C. Más allá de la tipología lítica: lectura diacrítica y experimentación como claves para la reconstrucción del proceso tecnológico. Zona Arqueol. 7, 145–160 (2006).

Soressi, M. & Geneste, J.-M. Reduction sequence, chaîne opératoire, and other methods: the epistemologies of different approaches to lithic analysis. The history and efficacy of the chaîne opératoire approach to lithic analysis: studying techniques to reveal past societies in an evolutionary perspective. PaleoAnthropology 2011, 334–350 (2011).

Titton, S. Lithic assemblage, percussive technologies and behavior at the Oldowan site of Barranco León (Orce, andalucía, Spain). [Tarragona]: Universitat Rovira i Virgili. (2021).

Pelegrin, J. A framework for analysing prehistoric stone tool manufacture and a tentative application to some early stone industries. Use Tools Hum. Non-Hum. Primates 30214, 44–57 (1993).

Inizan, M.-L., Reduron-Ballinger, M., Roche, H., Tixier, J. Technology and Terminology of Knapped Stone. C.R.E.P., Nanterre (1999).

Zhang, J. The site report of Jiahu, second edition. Science Press in Beijing (2015).

Yang, Y. et al. The site report of Jiahu in 2013. Kaogu (Archaeol. Chin.). 12, 3–19. (2017).

Li, H., Li, Z. Y., Gao, X., Kuman, K. & Sumner, A. Technological behavior of the early Late Pleistocene archaic humans at Lingjing (Xuchang, China). Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 11, 3477–3490 (2019).

Cohen, D. J. Microblades, early pottery, and the Palaeolithic-Neolithic transition in China. Rev. Archaeol. 24, 1–17 (2003).

Gao, X. & Pei, S. An archaeological interpretation of ancient human lithic technology and adaptive strategies in China. Quat. Sci. 26, 504–513 (2006).

Huan, F. X. et al. Technological diversity in the tropical-subtropical zone of Southwest China during the terminal Pleistocene: excavations at Fodongdi Cave. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 16, 25 (2024).

Ollé, A. et al. The earliest European Acheulean: new insights into the large shaped tools from the late Early Pleistocene site of Barranc de la Boella (Tarragona, Spain). Front. Earth Sci. 11, 1188663 (2023).

Lemorini, C. et al. Old Stones’ song: Use-wear experiments and analysis of the Oldowan quartz and quartzite assemblage from Kanjera South (Kenya). J. Hum. Evol. 72, 10–25 (2014).

Aleo, A. Comparing the formation and characteristics of use-wear traces on flint, chert, dolerite and quartz. Lithic Technol. 48, 130–148 (2023).

Ollé, A. et al. Microwear features on vein quartz, rock crystal and quartzite: A study combining Optical Light and Scanning Electron Microscopy. Quat. Int. 424, 154–170 (2016).

Clemente Conte I., Lazuén Fernández T., Astruc L., Rodríguez Rodríguez A. C. Use-wear Analysis of Nonflint Lithic Raw Materials: The Cases of Quartz/Quartzite and Obsidian. In: Marreiros J. M., Gibaja Bao J. F., Ferreira Bicho N., editors. Use-Wear and Residue Analysis in Archaeology [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2015. p. 59–81. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08257-8_5

Sussman, C. Microwear on quartz: fact or fiction? World Archaeol. 17, 101–111 (1985).

Broadbent, N. & Knutsson, K. An experimental analysis of quartz scrapers: results and applications. Fornvännen 70, 113–128 (1975).

Knight, J. Vein quartz. Lithics J. Lithic Stud. Soc. 12, 37–56 (2016).

Zhen, Y. & Jiang, L. The implications of the ancient rice found in the site of Shangshan. Kaogu (Archaeol. Chin.) 9, 19–25 (2007).

Museum Zhejiang Provincial Institute of Archaeology and Pujiang Museum. Pujiang Shangshan. Wenwu Press Beijing (2016).

Wang, J., Zhu, J., Lei, D. & Jiang, L. New evidence for rice harvesting in the early Neolithic Lower Yangtze River, China. PLoS One 17, e0278200 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to Dr. Andreu Ollé, Dr. Amèlia Bargalló Ferrerons, Anna Francès Abellán, Gloria Cattabriga, and Diego Capra for their invaluable assistance at the lithic lab in IPHES-CERCA, Spain. Special thanks are extended to Maria Guillen Espínola for contributing to the photographic documentation of the artefacts. We are also indebted to Dr. H. Fan, Dr. S. Zhou, and Dr. Y. Wang from the University of Science and Technology of China for their generous support during our fieldwork in China. W.Y.L. acknowledges funding support from the MSCA-COFUND R2STAIR Fellowship (GA 101034349), with the host institute of The Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution (IPHES-CERCA). W.Y.L.’s research also benefits from funding from the César Nombela program (2024-T1/PH-HUM-31586), as well as the Anhui Provincial Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project (AHSKQ2021D52). This research was also supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation through the “María de Maeztu” excellenceaccreditation (CEX2024-01485-M/funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033) (CEX2019-000945-M). DB is grateful for support from the Spanish project Early and Middle Pleistocene human technology, behavior and settlement patterns in their paleoenvironmental framework in Western Mediterranean (PID2021-123092NB-C21), as well as funding from the Generalitat de Catalunya Research Group (AGAUR) IPHES-URV Human Paleoecology of the Plio-Pleistocene (2021 SGR 01238).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.Y.L. and D.B. conducted the lithic analysis and co-authored the initial draft of the manuscript. J.Z.Z. and W.L.L. contributed to the fieldwork and provided critical input and revisions during the preparation of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, W., Barsky, D., Lan, W. et al. Lithic technology and potential functions of quartz flakes used by early farmers in Central China. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 459 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02023-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02023-z