Abstract

Studying Buddhism’s spatial distribution is important for inheritance and protection of cultural heritage. Using Buddhist site data, the spatial distribution, clustering characteristics and hotspots of different sects in China are analyzed and identified at the grid-cell scale using exploratory spatial data analysis (ESDA) and density field hotspot detection model (DFHDM). Buddhist sites are dense in southeast and sparse in northwest, with the Hu Line forming the core dividing line. ESDA indicates that Chinese Buddhism is highly concentrated in the southeast side of the Hu Line, Tibetan Buddhism hotspots are concentrated in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, and Theravada Buddhism clusters along the western Yunnan province. DFHDM further reveals that Chinese Buddhism exhibits multi-core distribution characteristics, Tibetan Buddhism forms a contiguous core area, and Theravada Buddhism is gradually weakening from Yunnan’s western border corridor toward the interior. This study provides an analytical framework for the protection of Buddhist cultural heritage and regional management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As an important part of human cultural and spiritual life, the study of religion has a profound historical background and academic significance and is also closely related to the protection and transmission of cultural heritage. As early as the 16th century, European and American scholars started focusing on the connection between religion and geography1, which laid the foundation for the introduction of the geography of religions. In 1967, Sopher pioneered the establishment of a research framework for the traditional geography of religions in his seminal work, Geography of Religions2, indicating the formalization of this concept as an independent discipline. The geography of religions, which is closely intertwined with geography, focuses on examining the spatial distribution and regional characteristics of religions3,4. It aims to reveal the mechanisms underlying the propagation of religions within geographic environment, their spatial patterns, their relationships with nature, and social and cultural interactions. Research in this field not only enhances the understanding of the spatial distribution of religion but also provides theoretical insights and methodological support for interdisciplinary research on the relationship between religion and geography. Moreover, it provides a unique perspective for understanding the spatial evolution of human civilization, cultural diversity, and the adaptability of religion to the environment, particularly relevant in the era of globalization and modernization. With many religious heritages facing the risk of being forgotten or destroyed, the study of religious geography reveals the interactive relationship between religious heritages and the natural, social and cultural environments, promotes the harmonious coexistence of the humanities and the natural environment, and contributes positively to the preservation and transmission of humanity’s valuable cultural heritage.

Originating in ancient India, Buddhism spread as a universal faith to Asia, especially China, Japan, and Korea, and localization practices were implemented successfully in these regions5, resulting in a diversity of schools and sects. Among them, Chinese Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism and Theravada Buddhism constitute the main schools of Buddhism in the world today, whereas new schools such as Nichiren Buddhism in Japan and Tendai Buddhism in Korea have enriched the diversity of this religion. Buddhism was introduced in China during the period of the Two Han dynasties (206 BC-220 AD), and after more than 2000 years of development and evolution, it has been deeply integrated with Confucianism and Taoism and has become an important part of Chinese culture6. In China, Buddhism is dominated by Chinese and Tibetan Buddhism, with Theravada Buddhism also occurring in the Yunnan region. Han Buddhism is located mainly in Han Chinese settlement areas, and since its introduction during the Eastern Han Dynasty, it has been integrated with traditional Chinese culture, forming a unique Buddhist system and profoundly impacting Chinese philosophy, literature and art. Tibetan Buddhism is a unique school derived from China7, that is concentrated in Tibetan-inhabited areas such as Tibet, Qinghai, Sichuan and Yunnan, and its spatial distribution and transmission pathways have been greatly influenced by the surrounding environment and urban development8,9 and have, in turn, notably affected the ecological environment and cultural landscape of Tibetan societies10,11,12. Theravada Buddhism, however, is predominantly found in Yunnan’s Dai and other ethnic minority regions, where it has significantly impacted local culture and living practices13.

In recent years, significant progress has been achieved in the field of religious geography, particularly in examining the spatial distribution and diffusion of religions in China14. Studies have shown that the spatial diffusion of Buddhism in China is characterized by significant regional differentiation, and Buddhism is concentrated in the southeastern and southwestern regions14. In Tibetan-inhabited areas, the spatial pattern of Gelugpa monasteries demonstrates multiscale variability15, whereas the main-subordinate monastery system of Tibetan Buddhism in the Hehuang area shows obvious spatial clustering characteristics and significant imbalances between different regions and sects16. Zhao and Su reconstructed the spread of Tibetan Buddhist sites in the Hehuang Valley region since the Song Dynasty through spatial and temporal sequence analysis methods and determined that their spatial distribution gradually changed from a multinucleated pattern to a strip-like pattern and exhibited cluster diffusion characteristics, with an increasingly significant spatial clustering trend7. At the regional scale, Tibetan Buddhism in Amdo city is concentrated in the eastern region due to the influence of the natural geographic environment, which demonstrates significant spatial clustering characteristics17. Zhu et al., on the basis of mathematical statistics and spatial analysis, revealed dual-core cluster distribution patterns of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in Qinghai Province, which are centered on Yushu and Hualong18. Wang and Zhou indicated that monasteries of the four major sects of Tibetan Buddhism are centrally distributed in the contiguous region of Yunnan, Tibet, and Sichuan, but the degree of concentration and the concentrated geographic area differ; moreover the scopes of the corresponding monastery blind zones and their distributions are not the same19. In addition, most monasteries in Golog Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture are located in areas 4000-4500 m above sea level, and their spatial distribution is closely related to the natural environment20. The geographic distribution of Buddhist sacred mountains, however, is concentrated in eastern China, especially east of the Hu Line, and these sacred mountains are distributed in a band along the northeast-southwest direction, with a particularly dense distribution in the southern‒central region along the Yangtze River21. From a spatiotemporal perspective, Chan et al. revealed the spreading characteristics of multiple religions in the Taipei metropolitan area from 1660-2020 through topological analysis22, and Buddhist temples and pagodas were distributed along the southwest-northeast direction in Liaoning, with the center of the distribution gradually moving toward the northwest and ultimately becoming focused on the western part of Liaoning. Gao et al. noted that the spatial pattern of Buddhist temples and pagodas in Liaoning Province exhibits a pronounced concentration and unevenness, with a pattern of more Buddhist temples in the west and north and fewer Buddhist temples in the east and south, with the western part of the province encompassing a significant high-density cluster23. However, most existing studies are limited to specific small- and medium-scale regions or single sects, but there is a lack of systematic research on the large-scale spatial scope and the characteristics of the spatial distribution of different Buddhist sects in China, which requires further in-depth exploration.

Therefore, from a geographic perspective, Buddhist sites in China are adopted as the research object, and global Moran’s I (GMI), local Moran’s I (LMI) and density field hotspot detection model (DFHDM) are applied comprehensively to analyze the spatial pattern and clustering characteristics of the three major Buddhist sects in China, as well as to determine their distribution hotspots. In addition, a 50 km × 50 km grid is adopted to analyze the spatial distribution of Buddhist sites in detail and reveal their spatial agglomeration and differentiation patterns from a microscopic perspective. This study offers a systematic groundwork for the preservation and transmission of Buddhist cultural heritage, while enriching the research paradigm of religious geography and enhancing the depth and breadth of exploration into the spatial distribution of religions.

Methods

Research design

This study draws on data from Buddhist sites across China, encompassing the three Buddhist sects: Chinese Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, and Theravada Buddhism. The study area is partitioned into grid units to facilitate a meticulous analysis. Initially, these grid units serve to visually depict the spatial distribution patterns of Buddhist sites. Subsequently, exploratory spatial data analysis techniques are applied to comprehensively examine the global spatial autocorrelation traits and local spatial agglomeration phenomena. Moreover, DFHDM model is utilized to accurately pinpoint hotspot distribution regions at varying scales for Buddhist sites. Finally, drawing from the research findings, conclusions are formulated, discussed, and prospects are explored (Fig. 1).

Study objects and data sources

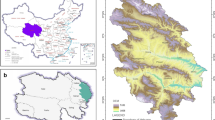

This study is based on the data of Buddhist sites provided by the National Religious Affairs Administration (https://www.sara.gov.cn/resource/common/zjjcxxcxxt/zjhdcsjbxx.html), and obtained spatial distribution information on a total of 34,059 Buddhist sites in China (excluding Taiwan Province, Hong Kong, and Macao Special Administrative Region). Among them, there are 28,498 Chinese Buddhist sites, 3857 Tibetan Buddhist sites, and 1704 Theravada Buddhist sites (Fig. 2). The characteristics of Buddhist sites of the three different sects are shown in Table 1. Tibetan population data for all provinces (autonomous regions and municipalities directly under the central government), from China Population Census Yearbook 2020.

Geographic grid analysis has demonstrated unique advantages in improving the precision and accuracy of spatial analysis models24. According to existing literature, the selection of grid scales must balance regional element consistency and feature representation accuracy. If larger-scale grids are used, such as 100 km × 100 km or 150 km × 150 km, their overly broad coverage range can easily lead to the intermingling of heterogeneous natural environments and human elements (such as administrative boundaries) within the grid24. Smaller grid scales, such as 10 km × 10 km or 30 km × 30 km, although they can improve spatial accuracy, China’s land area is approximately 9.6 million km², and small-scale grids will generate a massive number of grid cells, leading to the fragmentation of regional characteristics and significantly increasing the complexity of analysis. Additionally, given that 50 km grids are a commonly used scale in geographical research25,26,27,28,29, a 50 km × 50 km grid scale is appropriate for China, offering a reasonable balance between the number of grids and spatial precision. After repeated testing, the study determined a 50 km × 50 km grid as the basic research unit and divided the study area into 4119 grids. Spatial statistics and sect number extraction were conducted on Buddhist sites within the grids using the ArcGIS platform, systematically revealing the macro-level patterns and sect differentiation characteristics of Chinese Buddhism.

Research methodology

Exploratory spatial data analysis

GMI and LMI are used to investigate the spatial clustering characteristics of the three sects of Buddhism in the seven regions of China. GMI reveals the overall agglomeration of Buddhism in the seven regions, while LMI pinpoints the hot and cold spots of Buddhism in the seven regions.

GMI is employed to identify the overall spatial characteristics of Buddhist sites with the following expression30,31:

Where I stands for the global spatial autocorrelation index; xi and xj represent the count of Buddhist sites in the ith and jth grids, respectively; wij signifies the weight matrix of each grid. I takes the value in the range of [−1,1], when I is between [−1,0), the grids are negatively correlated with each other, and the closer to −1 signifying stronger negative correlation; when I lies between 0 and 1, it suggests a positive spatial correlation, with values closer to 1 indicating stronger positive correlation. The value of I is 0 implies no correlation, indicating a random distribution of the grids. Z-value, which is a standardized statistic of I, helps assess the clustering degree of Buddhist sites. z-value can be expressed as:

Where Var(I) denotes the number of variants and E(I) is the mathematical expectation of Buddhist sites. A larger absolute Z-value signifies a more positive or negative spatial correlation among Buddhist sites in China. Conversely, a Z-value tends to 0 implies insignificant result, suggesting a random distribution of Buddhist sites in China.

LMI was utilized to further analyze the spatial clustering and outlier distribution characteristics of Buddhist sites. To examine local autocorrelation, the Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) were employed32. The fomula is as follows:

Where I represents the local correlation index, wij’ denotes the row-normalization of wij, and Zi and Zj are the standard deviation normalized observations of the number of Buddhist sites in the grid. At a significance level of 5%, when both Ii and Zi are positive, it indicates a high-high clustering pattern; when Ii is negative and Zi is positive, it suggests a high-low agglomeration outlier; when Ii is positive and Zi is negative, it reveals a low-low clustering; and when both Ii and Zi are negative, it implies a low-high outlier. The LISA plot can show these four types of spatial clustering, namely, high-high, low-low, high-low and low-low, as well as the non-significant clusters.

Density field hotspot detection model

DFHDM can effectively realize the transformation from discrete points to continuous fields, and can extract, identify and express different forms and hierarchical structures of geographic objects from a large-scale range and a small sample size33. The study is based on the density surface of Buddhist sites in China for hotspot detection and explores the spatial density distribution characteristics of different sects of Buddhism on a national scale.

1. Based on kernel density estimation generate density surface

Kernel density estimation is used to generate the density field surface of Buddhist sites. The kernel density formula for calculating two-dimensional data is provided as follows34:

Here, \(f\left(x,y\right)\) is the estimated kernel density value at the Buddhist site (x, y). A higher kernel density value indicates a greater spatial concentration of Buddhist site, and conversely, the smaller it is. \({(x-{x}_{i})}^{2}+{(y-{y}_{i})}^{2}\) calculates the squared Euclidean distance between the Buddhist site point \(\left({x}_{i},{y}_{i}\right)\) and (x, y). r stands for the bandwidth, which serves as the search radius of kernel density estimation. n is the number of Buddhist site samples within this search radius. The function K(x) is the quadratic kernel function for spatial weighting, K is greater than 0.

Hotspot detection model

The hotspot detection method based on density surfaces was employed to address the difficulty of accurately identifying hotspot areas and peaks of Buddhist sites by relying only on the density surface model, thereby facilitating the quantitative characterization, description and analysis of hotspot patterns. First, a density field surface model for Buddhist sites was constructed based on the kernel density estimation method. The bandwidth notably affects the density surface results, and after many tests, an optimal bandwidth of 50 km was finally selected in this study. Second, the neighborhood image maximum surface was established using focal statistics to determine the location of the maximum in the local area. Then, a nonnegative surface was obtained through map algebra (on this density field surface, the positive domain is the region below the local maximum, whereas the zero domain is the local extreme-value region (here, the maximum)). Finally, via the use of the reclassification method, extreme regions were extracted, all hotspots were identified, and all hotspots were classified according to the location of point values on the surface of the original density field35.

Results

Spatial patterns of Buddhist sites in China at the grid scale

This study, employing grid cell analysis, reveals a spatial pattern of Buddhist sites in China characterized by widespread distribution but pronounced regional differentiation (Fig. 3). Nationwide, 50.52% of grid cells (2081) contain Buddhist sites, with marked spatial differentiation observed along the Hu Line. The southeast side of the Hu Line hosts the majority of China’s prominent Buddhist sites, with the East China region (encompassing Zhejiang, Fujian, and Jiangxi) and the Central China region (particularly Hunan Province) forming high-density core zones, predominantly centered around the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River. Conversely, Buddhist sites on the northwest side of the Hu Line are generally sparse, with a notable cluster forming in the Southwest China region (western Sichuan, eastern Tibet, etc.), primarily due to the influence of Tibetan Buddhism. The Northwest China region (including Xinjiang, northern Tibet, western Qinghai, and northern Inner Mongolia) and the northern parts of North China and Northeast China display large-scale low-density areas. This distribution pattern profoundly reflects the synergistic effects of natural geographical factors (such as the humid climate in the southeast and the cold, arid climate in the northwest) and human factors (including population density and cultural distinctions between the eastern and western regions).

The spatial distribution of Chinese Buddhist sites shows a pronounced gradient differentiation along the Hu Line. Over 90% of China’s Chinese Buddhist resources are concentrated on the southeast side of Hu Line. The East China core region, encompassing Zhejiang, Fujian, and Jiangxi province, forms a continuous high-density belt, while Central China, particularly Hunan province, serves as a secondary high-density zone. Together, these regions constitute the core Buddhist corridor along the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River. In contrast, Northeast and Southwest China display medium-to-low-density peripheral distributions of Buddhist sites. On the northwest side of the Hu Line, Buddhist sites are extremely scarce, with only sporadic occurrences in small areas of North and Northwest China adjacent to the line. This “core-periphery” pattern profoundly reflects the dual constraints of the Hu Line. The humid climate and agricultural civilization on the southeast side furnish the material and cultural foundations for Chinese Buddhism, whereas the cultural dominance of ethnic minorities on the northwest side acts as a barrier to its dissemination, leading to a virtual absence of Buddhism in regions such as the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and Xinjiang. This underscores the spatial coupling between religious distribution and regional human geography.

The pattern of Tibetan Buddhist sites is significantly influenced by the Hu Line, exhibiting an extreme “northwest core-southeast island” characteristic. The Northwest China region serves as the core area, concentrated in the core region of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, forming a continuous zone spanning eastern Tibet-western Sichuan-eastern Qinghai-southern Gansu. Within this zone, the southern Tibetan valley (Lhasa River basin) and the Amdo Corridor (Huangshui River valley) constitute the two highest-density cores, reflecting the deep adaptation of the Tibetan Buddhist culture to the harsh, high-altitude environment. The remaining areas of Gansu Province and parts of Inner Mongolia are also influenced by Tibetan Buddhism, resulting in its distribution in these regions. The southeast side of Hu Line is an isolated zone for the distribution of Tibetan Buddhism, with only scattered monasteries existing in the Northeast China region (such as the Ruiying Temple in Fuxin, Liaoning Province). These are religious and cultural transplants from Mongolian immigrants during the Qing Dynasty, confirming the rigid barrier effect of the Hu Line on the spread of Tibetan Buddhism- the main Han Chinese farming area southeast side of Hu Line lacks a cultural foundation for acceptance, which has prevented Tibetan Buddhism from spreading across the line on a large scale.

Tibetan Buddhism, practiced by Tibetans, Mongolians, Tu, and Naxi peoples, displays a distinct spatial pattern tied to ethnic regions. Crucially, its core distribution exhibits strong spatial coupling with Tibetan-populated areas (Fig. 4), with sites density increasing alongside Tibetan population density across the Tibetan Plateau and periphery. This forms a cultural-ethnic symbiosis. The three provinces with the largest Tibetan population (Tibet, Qinghai, and Sichuan) account for 86.5% of all Tibetan Buddhist sites nationwide, confirming the spatial dependency of religious sites as core carriers of ethnic culture. Conversely, eastern regions with sparse Tibetan populations have far fewer sites, underscoring the foundational role of ethnic demographics in shaping religious landscapes. Figure 4 also reveals a significant Tibetan Buddhist presence in Inner Mongolia, reflecting the religion’s deep connection to Mongolian culture and forming a secondary religious-ethnic coupling pattern. Nevertheless, Tibetan-inhabited areas remain central—as the religion’s birthplace, core cultural region, and home to its largest adherent group—their strong spatial coupling remains key to understanding Tibetan Buddhism’s geographical structure in China.

The distribution of Theravada Buddhist sites exhibits significant regional limitations. Its distribution is strictly limited to the territory of Yunnan Province, and forms a spatial pattern centered on the western border region of Yunnan (Xishuangbanna-Dehong-Lincang) with Puer in southern Yunnan as a secondary focal point, and the density decreases sharply from the border toward the interior. Overall, due to the barrier formed by the Hengduan Mountains and the influence of cross-border Dai-Thai ethnic cultural origins, its distribution remains primarily in the southeast side of the Hu Line.

Figure 5 illustrates the grid density data distribution of the three major Buddhist sects through a box plot, offering the key advantage of efficiently analyzing spatial heterogeneity in a statistically geometric manner. The interquartile range of Chinese Buddhist sites highlighted their extensive cross-regional dispersion, with the densest grid encompassing approximately 600 sites. The compact box plot for Tibetan Buddhist sites underscored their localized clustering, primarily on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, where the densest grid contains around 80 sites. In contrast, the data for Theravada Buddhist sites exhibited a more uniform distribution pattern, with the densest grid holding approximately 180 sites. Compared to conventional statistical indicators, box plot serves as a concise yet insightful analytical tool for examining the spatial patterns of Buddhism, as they account for three critical dimensions: dispersion, skewness, and outliers.

Characteristics of the spatial agglomeration of Buddhist sites

We applied GMI to detect the spatial autocorrelation of Buddhist sites in China, aiming to reveal the geospatial distribution characteristics and interconnectivity of these sites. We chose the contiguous edges-corners method to set the threshold, which accounts for the edge and corner contacts between geographic units and can reflect spatial proximity more comprehensively.

The detection results reveal that the GMI value of Buddhist sites in China is 0.5262, and the Z score reaches as high as 66.4677, with a p value of 0.00. These results indicate that Buddhist sites are geospatially clustered. Tibetan Buddhism, Chinese Buddhism and Theravada Buddhism all exhibit significant positive spatial correlation. Among them, Tibetan Buddhism attained the highest degree of spatial clustering, with a GMI value of 0.6423, which is significantly greater than those of Chinese Buddhism (GMI = 0.5438) and Theravada Buddhism (GMI = 0.4039) (Table 2). This result reflects the differences in spatial distribution among the various Buddhist sects, especially the more obvious geospatial clustering trend of Tibetan Buddhism.

GMI analysis conducted on China’s seven regions (Table 3) reveals that the distribution of Buddhism exhibited significant clustering characteristics across all regions. However, sectarian differentiation was profoundly constrained by the Hu Line. Chinese Buddhism was predominantly concentrated in the southeast side of the Hu Line, with the highest concentration levels observed in the Northeast China region (Moran’s I = 0.6001) and the Central China region (Moran’s I = 0.5263). Conversely, the Northwest China region (Moran’s I = 0.3697) on the northwest side of the Hu Line exhibited weak concentration, attributed to ethnic and cultural barriers. Tibetan Buddhism demonstrated high concentration in the northwest side of the Hu Line, with the Southwest China (Moran’s I = 0.6881) and Northwest China (I = 0.6207) region being the principal areas of concentration. In contrast, the Northeast China region (Moran’s I = 0.2995) in the southeast side of the Hu Line displayed a relatively weaker concentration, while the East China and Central China regions showed no significant spatial autocorrelation. Theravada Buddhism exhibited significant clustering solely in the Southwest China region (Moran’s I = 0.5936), with the remaining six regions inaccessible for analysis due to the absence of Theravada Buddhist sites, reflecting its constraint by the Hengduan Mountains. This finding indicates that the Hu Line acts as a threshold for religious and cultural ecology, shaping China’s Buddhist “southeast diffusion-northwest concentration” dialectical pattern through the synergistic influence of natural barriers and humanistic factors.

Furthermore, LMI was employed to identify spatial distribution clusters and outliers of Buddhist sites across China’s seven regions for revealing their spatial dependence and heterogeneity characteristics, and the results are shown in Fig. 6. The analysis results demonstrated that the spatial distribution of Buddhist sites exhibits a significant regional differentiation pattern, with the majority concentrated in the southeast side of the Hu Line. Overall, high-high clustering areas are distributed across all seven regions, but the southeast side of the Hu Line serves as the core area. In contrast, low-low clustering areas are primarily scattered across the other six regions, except for the Northwest China region.

Specifically, among different Buddhist sects, the spatial distribution of Chinese Buddhist sites exhibits particularly pronounced. High-high clustering areas area predominantly concentrated on the southeast side of the Hu Line, encompassing the Liaodong Peninsula in the Northeast China, southern Hebei and northeastern Shanxi in North China, the coastal areas of Zhejiang and Fujian and the Fujian-Jiangxi border region in East China, northern Guangdong in South China, eastern Hubei and Hunan in Central China, central and western Yunnan, the Chengdu-Chongqing area, and northeastern Guizhou in Southwest China, along with the southern Shaanxi, southern Gansu and parts of Ningxia in the Northwest China. Conversely, the low-low clustering areas are primarily distributed in Shandong, northern Anhui, and northern Jiangsu in the southeast side of the Hu Line, as well as western Henan and western Hubei in Central China, western Guangxi and southern Hainan in South China, and the marginal rigions north of North China and northwest of Northeast China in the northwest side of the Hu Line.

For Tibetan Buddhism, high-high clustering areas are strictly confined to the traditional Tibetan Buddhist cultural region in the northwest of the Hu Line, with hotspots concentrated in southern Tibet, eastern Tibet, western Sichuan, and eastern Qinghai. Sattered hotspots are observed only on the southeast side of the Hu Line, primarily the Xing’an League and Tongliao City of Inner Mongolia, as well as Liaoning Province. Low-low clustering areas are widely distributed in the agricultural regions in the southeast side of the Hu Line, including East China, Central China, South China, and the eastern part of Southwest China, while in the northwest side of the Hu Line, they are found in the high-altitude cold regions of northern Tibet. Theravada Buddhism demonstrates extreme localization, with high-high clustering areas restricted to the southwestern border of Yunnan (such as Xishuangbanna), and no significant low-low areas identified.

Hotspot detection for the different Buddhist sects

In this study, kernel density estimation was used to quantitatively analyze the spatial distribution characteristics of Buddhist sites, and the results revealed that the spatial distributions of the different Buddhist sects exhibit significant regional differentiation characteristics. In general, the hotspot areas of Buddhist sites mainly demonstrated multicore faceted distribution characteristics, concentrating on the southeast side of the Hu line in East China (the southern bank area of the lower Yangtze River), Central China and Southwest China (the western border area of Yunnan Province), while the intensity of the hotspot in the northwest side of the Hu line is relatively weaker, forming a “strong agglomeration in the southeast and weak diffusion in the northwest” gradient pattern.

Specifically, the kernel density hotspot areas of Chinese Buddhist sites were concentrated in East China and Central China. A distinct multi-core pattern emerges in the southeastern area of the lower Yangtze River basin, where the southeastern coastal region exhibits pronounced contiguous distribution characteristics. Tibetan Buddhism is presented as a large core contiguous core area in Tibet and Qinghai, located in Northwest China. The hotspot of Theravada Buddhism is situated in the border corridor of western Yunnan, Southwest China, with the intensity of the hotspot demonstrating a gradual weakening diffusion trend from the periphery towards the interior.

On the basis of the kernel density estimation results, the density field detection model was adopted to identify and extract density distribution hotspot areas of the sites of the different Buddhist sects in China, thereby capturing distribution hotspot areas of the different Buddhist sects hierarchically and quantitatively. Through the use of the natural breakpoint method, we classified the kernel density values into five classes: large, medium-large, medium, small-medium and small hotspots (Fig. 7).

As shown in Table 4, there were 5 large-scale hotspots of Chinese Buddhism, accounting for 1.23% of all hotspots, which were distributed mainly in the eastern coastal area of Fujian Province and eastern Zhejiang Province in East China, and Hubei Province in Central China. Moreover, 17 medium-large hotspots were identified, accounting for 4.17% of the total, which were centrally located in the southern area of the lower reaches of the Yangtze River. There are 271 small hotspots, widely distributed on the southeast side of the Hu Line, with only a few extending into Northwest China (Shaanxi, Inner Mongolia, and Xinjiang), reflecting the synergistic effects of the spread of agricultural civilization and waterway networks.

A total of 230 hotspots of Tibetan Buddhist sites were identified, including 6 large hotspots, accounting for 2.61% of the total, which were concentrated in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau region. 16 medium-large hotspots, representing 6.96% of the total, exhibited a curvilinear belt-shaped distribution along the Tibet-Qinghai-Sichuan. The largest number of small hotspots, totaling 115 and accounting for 50%, were concentrated on the northwest side of the Hu Line, with scattered distributions on the southeast side, reflecting the influence of the high-altitude cold environment and the Tibetan population on the dissemination process.

Theravada Buddhism hotspots was the smallest, with a total of 11 identified, all located in the western border region of Yunnan Province. Notably, there were 3 large hotspots, accounting for 27.27% of the total hotspots; 1 medium-large hotspot, accounting for 9.09% of the total hotspots; 3 medium hotspots, accounting for 27.27% of the total hotspots; and 4 small hotspots, accounting for 36.36% of the total hotspots. Moreover, no small-medium hotspots were identified. This distribution pattern highlights the geographical barrier formed by the Hengduan Mountains and the interactive constraints stemming from the cross-border Dai-Thai cultural sphere.

Discussion

This study combines exploratory spatial data analysis and DFHDM to achieve a detailed description of the spatial differentiation and hotspot distribution of sites of the different Buddhist sects in China, utilizing geographically divided grid cells as the basis. It transcends the analytical limitations of traditional religious geography, which typically uses provinces or cultural regions as units of analysis. Compared with Chao et al.’s focused analysis of the diffusion process of Gelugpa monasteries in Tibet and Fang et al.’s quantitative spatial characterization of Tibetan Buddhism in the U-Tsang region36,37, this study precisely identifies three spatial pattern, the “multi-core distribution” of Chinese Buddhism, the “highland aggregation” of Tibetan Buddhism, and the “border aggregation” of Theravada Buddhism. Consequently, this provides a replicable grid-based analytical framework for religious geography research.

The distributions of the three major Buddhist sects revealed significant spatial differences. From the perspective of Weber’s sociology of religion, this distribution not only reflects the spatial logic of religious diffusion but also reflects the in-depth mechanism of multicultural integration in China38. Compared with Sopher’s study on the geographical distribution of religions2, the distribution of Buddhist sects in China shows more significant cultural and geographical characteristics39. Compared with Huntington’s clash of civilizations theory, the spatial distribution pattern of Chinese Buddhist sites highlights the possibility of cultural symbiosis and fusion40 and epitomizes the cultural pattern of plurality and unity of China, reflecting cultural interaction and fusion41, which provides a new perspective for understanding religious and cultural interactions within the context of globalization.

The “dense in the southeast and sparse in the northwest” pattern of Chinese Buddhism highlights the integration and reshaping influence of the Central Plains agricultural civilization on local beliefs. Its global impact is notably exemplified by the monastery clusters along the lower Yangtze River, which functioned as a hub for Buddhist dissemination in East Asia. During the Tang Dynasty, the Japanese monk Gishin studied at Guqing Temple on Mount Tiantai and subsequently founded the Japanese Tiantai School. In the Southern Song Dynasty, Japanese monks successively practiced Zen at Jiangxin Temple in Wenzhou and Tiantong Temple in Ningbo, respectively establishing the Japanese Rinzai and Soto schools. This confirms that the core region of the lower Yangtze River was a pivotal node in the global spread of Buddhist culture. Its formation was not only based on the material foundation of the densely populated and agrarian southeastern region but also benefited from cross-cultural interaction opportunities facilitated by the Maritime Silk Road.

A notable correlation exists between the spatial differentiation of Buddhist sects and the geographical barrier delineated by the Hu Line. This study revealed that the southeast side of the Hu Line constitutes the main agglomeration area of Buddhist sites, with the southeastern coastal area along the Yangtze River showing a significantly high agglomeration density, which echoes the findings of Qiu et al. for Buddhist sacred mountains, which are situated in the southern-central area along the Yangtze River21. During the flourishing period of Buddhism in the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420-589 AD), the economic and cultural centers were close to the Yangtze River42. The high density of Buddhist monasteries in the southeastern coastal region confirms the diffusion of Chinese Buddhism based on land and water transportation networks and population and economic centers, with a high degree of spatial overlap with the legacy sites of the ancient Silk Road and canal system.

Key findings of this study indicate that hotspots of Chinese Buddhism follow a multi-core distribution pattern. Taking the distribution of Buddhist sites in Zhejiang Province as a case, it boasts the highest number of temples nationwide, with roughly 4000, which is the result of the synergistic effects of geographical environment and cultural factors. Firstly, Zhejiang’s terrain, characterized by “seventy percent of the land is mountains, ten percent is water, the rest twenty percent is farmland”, aligns with Buddhism’s philosophy of “seclusion and spiritual cultivation”. Many temples are built on mountains, offering both seclusion from the world and natural nourishment, thus providing ideal conditions for the distribution and development of Buddhist temples. Second, Zhejiang has a long-standing commercial tradition and a prosperous economy, with the populace holding a deep and sincere faith in Buddhism. Donations from believers have become the economic pillar supporting the growth and development of temples. Even when ancient temples were damaged by war, public donations facilitated their restoration, expansion and onto the global stage. Thirdly, throughout history, emperors and officials have placed great value on Buddhism. For example, during the Kangxi era, the official government allocated funds to rebuild Putuo Mountain’s Puji Temple, and during the Yongzheng era, the official government was granted to repair Lingyin Temple. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the government actively supported the restoration and reconstruction of Buddhist temples, providing financial and policy support to ensure their stable development43.

The high concentration of Tibetan Buddhism coincides with Zhong and Bao’s spatial distribution of Tibetan Buddhism, i.e., the Tibetan Plateau, with Tibet and Qinghai at its core, constitutes the main area of Tibetan Buddhism44, which emphasizes the close connection between national cultural communities and geographic space. Tibet’s geographical proximity to India and Nepal resulted in Tibetan Buddhism primarily originating from India45. Similarly, following the destruction of Indian Buddhism by Muslim invasions, numerous Buddhists fled to Nepal and Tibet with scriptures and artifacts, driving the prosperity of Buddhism in both regions. The notable agglomeration of Tibetan Buddhism on the Tibetan Plateau not only reflects the natural barrier effect of high-altitude topography on religious propagation36 but also reflects the spatial coupling mechanism between religious centers and local power under the unification of churches and the state8 and the comprehensive evolutionary history of different sectarian forces interacting with each other over historical time and space19.

The distribution of Theravada Buddhism along the western border of Yunnan is similar to the spreading path of Theravada Buddhism in Southeast Asia46. Both originated in India and were transmitted via land routes to Southeast Asia and Yunnan Province in China during the 7th century. With the support of local governments, both adhered to the Pali scriptures and conservative precepts, forming a cross-border “Theravada Buddhist cultural circle”. This enabled regions such as Xishuangbanna and Dehong in Yunnan to share the same religious system with Myanmar and Thailand47. Theravada Buddhist monasteries are chiefly clustered in low-altitude regions. The mountainous broad-valley landscape in the southwestern border of Yunnan offers a conducive environment for their survival and dissemination48. This region is also a multi-ethnic hub, home to the Dai, Blang, and De’ang ethnic groups, who are the main followers of Theravada Buddhism. Given factors including geography, transportation networks, cultural context, and ethnic diversity, Theravada Buddhism hasn’t made inroads into the Yangtze River basin.

Studies have shown that the spatial agglomeration characteristics and hotspot distributions of Buddhist sites are significantly associated with historical transmission paths, ethnocultural boundaries, and geographic constraints16,49,50. In Chinese history, the rise and fall of religions depended on local regimes and policy orientations, ebbing and flowing with dynastic changes51. In modern times, Buddhism from Shanghai has dominated Buddhism in China by virtue of economic capital accumulation and geographic advantages, and Master Taixu’s reforms and secularized groups laid the foundation for the modernization of Chinese Buddhism52. Since the restoration of religious tolerance policies in 1982, historical religious sites have contributed to the mainstream process of Buddhist downtowns, and their spatial agglomeration patterns reflect the interplay of economic, political, and cultural capital components, as well as their in-depth integration with the urban environment53.

It is worth noting that temples are only one of the material cultural carriers for the spread of Buddhism, and should also include pagodas, cave temples. Taking cave temples as an example, their spatial distribution is notably environment-dependent, predominantly found on the precipitous cliffs of high-altitude mountain peaks with steep gradients54. Spatial-temporal analysis of Zhejiang Province indicates that the number of cave temples increased significantly during the Sui-Tang to Song-Yuan Dynasties periods55. For instance, cave temples in the central mountainous areas of southern Zhejiang are primarily distributed along the cliffs or in caves of medium-to-low mountains. This spatial pattern illustrates how historical trajectories, cultural determinants, and ecological contexts jointly structured the regional divergence of Buddhist heritage’s material expressions, furnishing empirical grounding for spatial analyses of Buddhist cultural diffusion and offering pivotal directions for advancing future research in this field.

Compared with previous studies, this study achieved progress in the following aspects. First, the spatial distribution characteristics of Buddhist sites were analyzed in a fine-grained manner using a grid as a unit, which is a more microscopic study scale and can more accurately reveal the spatial agglomeration and differentiation patterns of Buddhist sites. Second, the distribution of sites of the three Buddhist sects, i.e., Chinese Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, and Theravada Buddhism, was explored systematically and comparatively, thereby overcoming the limitations of previous studies, which were mostly limited to a single sect or a specific region. Thus, this study revealed the diversity and complexity of Buddhist sites in China more comprehensively.

In future research, the mechanism underlying the interactive influences of the natural geographic environment, socioeconomic conditions, and historical-cultural inheritance on the spatial distribution of Buddhist sites can be explored further, to reveal its hierarchical driving law through multi-scale nested analysis (e.g., grid-county-watershed). Secondly, local records, archaeological data and remote sensing images should be integrated to conduct a spatio-temporal database of Buddhism in different periods (Tang-Song, Ming-Qing and contemporary). Subsequently, spatial panel modeling and event history analysis can be utilized to quantify the natural-social-historical coupling effects in the evolution of Buddhist distribution. Finally, typical areas such as Wutai Mountain and Lhasa Valley will be selected. By combining high-resolution historical maps with multi-source spatio-temporal data, the dynamic correlation between Buddhist propagation paths and regional development over centuries will be analyzed. The above studies will break through the limitations of single-scale and static perspectives, expanding the interpretive dimension of religious geography at both methodological and theoretical levels. Meanwhile, they will provide scientific support for the dynamic protection of Buddhist cultural heritage and the planning of cross-regional cultural corridors.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Kong, L. Geography and religion: Trends and prospects. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 14, 355–71 (1990).

Sopher, D. E. Geography of Religions. (Prentice Hall, 1967).

Fousek, J. et al. Spatial constraints on the diffusion of religious innovations: The case of early Christianity in the Roman Empire. PloS One 3, e0208744 (2018).

Stump, R. W. The geography of religion: Introduction. J. Cult. Geogr. 7, 1–3 (1986).

Rubenstein, J. M.The Cultural Landscape: An Introduction to Human Geography. (Pearson, 2018).

Oh, K. N. The Taoist influence on Hua-Yen Buddhism: A case of the Sinicization of Buddhism in China. Chung-Hwa Buddh. J. 13, 277–97 (2000).

Zhao, Z. & Su, R. Spatial diffusion and driving factors of Tibetan Buddhist temples in the Hehuang Valley Region after Song Dynasty. Econ. Geogr. 43, 220–9 (2023).

Zhang, Y. & Wei, T. Typology of religious spaces in the urban historical area of Lhasa, Tibet. Front. Archit. Res. 6, 384–400 (2017).

Ding, B. The influence of geographical environment on the spread and development of Tibetan Buddhism in the Gansu-Qinghai Region. J. Qinghai Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 46, 17–25 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Traditional beliefs, culture, and local biodiversity protection: An ethnographic study in the Shaluli Mountains Region, Sichuan Province, China. J. Nat. Conserv. 68, 126213 (2022).

Gadan, D. & Zhang, Z. Spiritual places: Spatial recognition of Tibetan Buddhist spiritual perception. PloS One 19, e0301087 (2024).

Cui, N. et al. Buddhist monasteries facilitated landscape conservation on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Landsc. Ecol. 37, 1559–72 (2022).

Liang, X. & Gao, X. The historical context and characteristics of theravada buddhism cultural communication between Yunnan and southeast Asia. J. Asia Soc. Sci. (2021).

Tang, Y., Lin, X. & Lu, Y. Spatial distribution and diffusion patterns of four major religions in china: A discussion of religious development in different types of cities. Geogr. Res. 42, 2466–89 (2023).

Chao, Z., Zhao, Y. & Liu, G. Multi-scale spatial patterns of Gelugpa monasteries of Tibetan Buddhism in Tibetan Inhabited Area, China. GeoJournal 87, 4289–310 (2022).

Li, W. et al. Spatial distribution characteristics of Tibetan Buddhism principal-subordinate monastery systems in the Hehuang region. Herit. Sci. 12, 337 (2024).

Yang, Y. et al. Deciphering evolutionary patterns and multifaceted drivers of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in Amdo’s Tibetan Inhabited Area, China. Trans. GIS. 29, (2025).

Zhu, L. S. H., Zhang, P. & Li, Z. Spatial and temporal evolution of Tibetan Buddhist Monasteries in Qinghai province. World Reg. Stud. 28, 209–16 (2019).

Wang, L. & Zhou, Z. Regional differentiation of temples of Tibetan Buddhism in adjacent area of Yunnan, Tibet and Sichuan. Area. Res. Dev. 36, 171–6 (2017).

Xiao, Y. et al. GIS-based distribution and land use pattern of the monasteries in Guoluo Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in China. Bian, F. & Xie, Y. Geo-informatics in Resource Management and Sustainable Ecosystem. (Springer. 2016).

Qiu, M., Pei, Q. & Lin, Z. The geography of religions: Comparing Buddhist and Taoist sacred mountains in China. Geogr. Res. 61, 58–70 (2023).

Chan, C. H. et al. Spatiotemporal topology of religious spread in a multi-religious metropolis: A historical religious profile of Taipei City in Taiwan from 1660 to 2020. Geogr. J. 191, (2025).

Gao, J. et al. Spatio-temporal distribution characteristics of Buddhist temples and pagodas in the Liaoning region, China. Buildings 14, 2765 (2024).

Li, J., Wang, X. & Li, X. Spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of Chinese traditional villages. Econ. Geogr. 40, 143–153 (2020).

Luo, W. et al. Spatiotemporal evolution and driving factors of urban-rural integration in China. Prog. Geogr. 42, 629–643 (2023).

He, X. & Li, F. Spatial distribution and influencing factors of China’s 5a-rated tourist attractions based on geographic grid. Mt. Res. 42, 507–518 (2024).

Yang, X. et al. Insights into plant biodiversity conservation in large river valleys in China: A spatial analysis of species and phylogenetic diversity. Ecol. Evol. 12, e8940 (2022).

He, X., Li, F. & Gao, J. Spatial distribution and influencing factors of Chinese traditional villages based on geographic grid. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 44, 995–1004 (2024).

Xie, Z. et al. Macro-scale land hydrological model based on 50km * 50km grids system. J. Hydraul. Eng. 76-82 (2004).

Gatrell, A. C. Autocorrelation in spaces. Environ. Plan. A. 11, 507–16 (1979).

Li, X. et al. Spatial effect of mineral resources exploitation on urbanization: A case study of Tarim River Basin, Xinjiang, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 22, 590–601 (2012).

Anselin, L. Local indicators of spatial associatin-lisa. Geogr. Anal. 27, 93–115 (1995).

Li, Y. et al. Spatial distribution and influencing factors of traditional villages based on density field hot spot detection model-A case study in Southwest China. Journal of Southwest University (Natural Science Edition) 46, 178-187 (2024).

Silverman, B. W. Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis. (Chapman&Hall, 1986).

Zhang, H. et al. Hotspot discovery and its spatial pattern analysis for catering service in cities based on field model in GIS. Geogr. Res. 39, 354–69 (2020).

Chao, Z. et al. Spatial diffusion processes of gelugpa monasteries of Tibetan Buddhism in Tibetan Areas of China utilizing the multi-level diffusion model. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 27, 64–81 (2024).

Fang, S. et al. Quantitative characteristics and influencing factors of Tibetan Buddhist religious space with monasteries as the carrier: A case study of U-Tsang. China Herit. Sci. 12, 93 (2024).

Weber, M. The Sociology of Religion. (Beacon Press, 1993).

Liu, Y. Mobility and connection: The impact of urban commercial development on Buddhist monastic space in modern China. Relig. Stud. 157-61 (2022).

Huntington, S. P.The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. (Simon & Schuster, 1996).

Shao, W. Characteristics of spatial and temporal distribution and structure of the development of Chinese Buddhism and Tibetan Buddhism in Hexi Corridor. J. West. 24-7 (2024).

Chen, K. K. S.Buddhism in China: A Historical Survey. (Princeton University Press, 1972).

Yi, F. A Study on the site selection and spatial layout of Han Chinese Buddhist monasteries. PhD thesis (Wenzhou University, China, 2021).

Zhong, Y. & Bao, S. Space-time analysis of religious landscape in China. Trop. Geogr. 34, 591–8 (2014).

Ou, D. Indian Buddhism and Tibetan Buddhism: Origins and Correlations. South Asian Studies Quarterly 67-71+86+65 (2015).

Swearer, D. K.The Buddhist World of Southeast Asia. (State University of New York Press, 1995).

Huang, X. Transformation from Yunnan Theravada Buddhism to China Theravada Buddhism-Reflections on contemporary Yunnan Theravada Buddhism identity change. Social Sciences in Yunnan 119-122+186 (2017).

Peng, W. et al. Spatial differentiation characteristics and influencing factors of buddhist monasteries in Yunnan Province. Tropical Geogr. 44, 315–325 (2024).

Zou, H. et al. The spatial distribution characteristics and land use pattern of Tibetan Buddhism temples in Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture of Golog,. China Ecol. Sci. 43, 120–8 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Spatial correlation between traditional villages and religious cultural heritage in the Hehuang region, Northwest China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1080/13467581.2024.2373821 (2024).

Feuchtwang, S. Popular Religion in China: The Imperial Metaphor. (Routledge, 2001).

Huang, W. The new faces of urban buddhism //Juequn. The propagation model of urban Buddhism. (China Religious Culture Publisher, 2019)

Huang, W. Secularity and urban gentrification: An spatial analysis of downtown Buddhist temples in Shanghai. Space Cult. 26, 229–41 (2023).

Zhu, L. et al. Distribution and natural environment background of sites in Hexi region, Gansu, China. J. Desert Res. 41, 121–128 (2021).

Zou, J. et al. Spatio-temporal evolution of cultural sites and influences analysis of geomorphology in historical period of Zhejiang Province. J. Hangzhou Norm. Univ.(Nat. Sci. Ed.) 21, 190–203 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects (Grant No. 202401AS070037); China Scholarship Council (CSC No. 202308530254); “Yunnan Revitalization Talent Support Program” in Yunnan Province (grant numbers XDYC-QNRC-2022-0740, XDYC-WHMJ-2022-0016); Yunnan Province Philosophy and Social Science Innovation Team Project (2023CX02).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.X.L.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing—original draft. W.Y.: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. W.Y.M.: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. Y.Y.Y.: Funding acquisition, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. L.Y.Y.: Data curation, Software. G.Z.H.: Data curation, Software.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yue, X., Wang, Y., Wu, Y. et al. Grid-scale analysis of the spatial pattern and hotspot detection of Buddhist sects in China. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 449 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02026-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02026-w